Abstract

Background and Purpose

Transmembrane member 16A (TMEM16A), an intrinsic constituent of the Ca2+‐activated Cl− channel, is involved in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and hypertension‐induced cerebrovascular remodelling. However, the functional significance of TMEM16A for apoptosis in basilar artery smooth muscle cells (BASMCs) remains elusive. Here, we investigated whether and how TMEM16A contributes to apoptosis in BASMCs.

Experimental Approach

Cell viability assay, flow cytometry, Western blot, mitochondrial membrane potential assay, immunogold labelling and co‐immunoprecipitation (co‐IP) were performed.

Key Results

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) induced BASMC apoptosis through a mitochondria‐dependent pathway, including by increasing the apoptosis rate, down‐regulating the ratio of Bcl‐2/Bax and potentiating the loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential and release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm. These effects were all reversed by the silencing of TMEM16A and were further potentiated by the overexpression of TMEM16A. Endogenous TMEM16A was detected in the mitochondrial fraction. Co‐IP revealed an interaction between TMEM16A and cyclophilin D, a component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). This interaction was up‐regulated by H2O2 but restricted by cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of cyclophilin D. TMEM16A increased mPTP opening, resulting in the activation of caspase‐9 and caspase‐3. The results obtained with cultured BASMCs from TMEM16A smooth muscle‐specific knock‐in mice were consistent with those from rat BASMCs.

Conclusions and Implications

These results suggest that TMEM16A participates in H2O2‐induced apoptosis via modulation of mitochondrial membrane permeability in VSMCs. This study establishes TMEM16A as a target for therapy of several remodelling‐related diseases.

Abbreviations

- ANT

adenine nucleotide translocase

- BASMCs

basilar artery smooth muscle cells

- CaCC

Ca2+‐activated Cl− channel

- CCK‐8

Cell Counting Assay Kit‐8

- co‐IP

co‐immunoprecipitation

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- Cyt‐c

cytochrome c

- IMM

inner mitochondrial membrane

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- mPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- OMM

outer mitochondrial membrane

- TMcon

control cohorts of vascular smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice

- TMEM16A

transmembrane member 16A

- TMTg

vascular smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice

- VDAC

voltage‐dependent anion channel

- VSMCs

vascular smooth muscle cells

Introduction

Apoptosis is critical for maintaining normal cell number and tissue homeostasis. Apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) is a common feature of vascular remodelling. Together with proliferation, migration and matrix turnover, it contributes to changes in vascular architecture in the development of various diseases, including hypertension, stroke and atherosclerosis (Gurbanov and Shiliang, 2006; Scull and Tabas, 2011). During apoptosis, cells undergo morphological changes that are related to the movement of different ions across the cell membrane (Kondratskyi et al., 2015; Wanitchakool et al., 2016). Although the mechanism of apoptosis in VSMCs has not been fully established, there is some evidence to indicate that some Cl− channels are involved, including the Cl− channels http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/FamilyDisplayForward?familyId=128#702 (Qian et al., 2011) and http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=707 (Zeng et al., 2014) and http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=5377 (Jiang et al., 2013). However, it is not known whether other Cl− channels also contribute to apoptosis in VSMCs.

Transmembrane member 16A (TMEM16A), also known as ANO1 or DOG1, is an intrinsic constituent of the http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/FamilyDisplayForward?familyId=130 (CaCC) with important physiological functions in VSMCs and other cell types (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2017). In the cardiovascular system, TMEM16A is related to the regulation of BP (Heinze et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2017), vascular remodelling (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015), vasoconstriction (Bulley et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012; Dam et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016) and ischaemia‐induced arrhythmia (Ye et al., 2015). Previous studies from our laboratory and others have demonstrated that TMEM16A is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and hypertension‐induced cerebrovascular remodelling (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015), suggesting that a link between TMEM16A and apoptosis might also exist in VSMCs.

The coding sequence of TMEM16A is located within the 11q13 region, which contains a stretch of proteins associated with the cell cycle, proliferation and apoptosis. Hence, the complex structure of this amplicon has mostly been studied in cancer cells (Wilkerson and Reis‐Filho, 2013). Previous studies showed that the knockdown of TMEM16A or using a specific inhibitor of TMEM16A induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells (Britschgi et al., 2013), PC‐3 and CFPAC‐1 cells (Seo et al., 2015) and gastrointestinal stromal tumour cells (Berglund et al., 2014). However, studies in different cancer cells revealed a different role for TMEM16A in apoptosis. Inhibition of TMEM16A did not influence apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Deng et al., 2016). It appears that the function of TMEM16A in apoptosis varies in different kinds of cells. Moreover, the role of TMEM16A in the apoptosis of VSMCs is unknown.

The basilar artery is the largest resistant artery in the brain, and its pathological remodelling increases the risk of stroke. Our previous studies demonstrated that TMEM16A inhibits proliferation in basilar artery smooth muscle cells (BASMCs) and ameliorates hypertension‐induced cerebrovascular remodelling (Wang et al., 2012). Recent findings revealed that TMEM16A promotes apoptosis of pulmonary endothelial cells (ECs) (Allawzi et al., 2018). Therefore, we assumed that TMEM16A had a facilitatory effect on apoptosis in BASMCs, unlike its effect observed in cancer cells. In this study, we determined the functional role of TMEM16A in hydrogen peroxide (http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=2448)‐induced apoptosis in BASMCs from rats and from TMEM16A vascular smooth muscle‐specific transgenic mice and further explored whether the underlying mechanisms were mediated by a mitochondria‐dependent pathway.

Methods

Vascular smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice

All animal experiments in this study were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Sun Yat‐sen University and complied with the standards for care and use of animal subjects as stated in the ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ (issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, Beijing). Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015). Animals were maintained in pathogen‐free facilities with a 12 h light/dark cycle and fed a standard rodent diet with water ad libitum. The sample numbers used in this study followed the principle of minimal requirement and are shown in the figure legends.

The vascular smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice (TMTg) were designed and produced by Cyagen (Suzhou, China) as previously described (Ma et al., 2017). The genetic background of all the mice used in this study was C57BL/6J. The transgene construct consisted of the following components: pRP.ExBi‐CMV‐LoxP‐Stop‐LoxP‐TMEM16A. To obtain mice exhibiting vascular smooth muscle‐specific overexpression of TMEM16A, transgenic founders were bred with mice expressing a Tagln‐Cre transgene (STOCK Tg (Tagln‐cre)1Her/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA, USA). The control cohorts were TMEM16A transgenic mice that did not express Tagln‐Cre (TMcon).

Cell culture

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (80–100 g) were supplied by the Experimental Animal Centre of Sun Yat‐sen University (Guangzhou, China). Rat BASMCs were cultured as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, rats were anaesthetized with 2,2,2‐tribromoethanol (240 mg·kg−1) i.p. and then decapitated. Basilar arteries were rapidly removed and cut into small pieces of 0.5 mm. The tissues were plated in DMEM/F‐12 containing 20% FCS and cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. Cells were passaged using 0.2% trypsin, and passages of 6 to 12 were used for further experiments. The method used to culture mouse (male, 8–10 weeks) BASMCs was similar to that used for rat. BASMCs were identified by immunofluorescent staining of α‐actin and by the characteristic ‘hill and valley’ growth pattern.

siRNA transfection and plasmid transfection

The siRNA duplex against the rat TMEM16A gene (GeneBank Accession No. NM_001107564, 5′‐GGAGUUAUCAUCUAUAGAATT‐3′) was designed and constructed by Qiagen and transiently transfected with Hiperfect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). A negative siRNA (Qiagen) was used as negative control. Forty‐eight hours later, the cells were used for experiments.

The TMEM16A plasmids were transfected as described previously (Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, BASMCs were plated in six‐well plates at a density of 2–4 × 106 mL−1 for 24 h. Then, the plasmids were transfected into the cells with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen™; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) in OPTI‐MEM I reduced serum medium (Invitrogen™; Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 6 h, the cells were switched to normal culture medium for another 42 h and then used for experiments.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured by Cell Counting Assay Kit‐8 (CCK‐8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) as described previously (Zeng et al., 2014). In brief, BASMCs were seeded in 96‐well plates at a density of 1–2 × 104 cells·mL−1 for 24 h followed by H2O2 treatment (200 μmol·L−1) for 24 h. Then 10 μL of CCK‐8 regent was added to each well for 2 h, and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio‐Tek, Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability was normalized to control.

Quantification of apoptosis by flow cytometry

BASMC apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry using an Annexin V‐FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGEN Biotech, Nanjing, China) following the established method in our lab (Zeng et al., 2014). BASMCs were digested with trypsin and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 mL−1. Cells were washed with cold PBS twice and suspended in a binding buffer, and then cells were incubated with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) in the dark at room temperature for 15 min. The samples were analysed within 30 min using a Beckman‐Coulter EPICS XL‐MCL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Mitochondrial membrane potential test

The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was detected using a 5,5′,6,6′‐tetrachloro‐1,1′,3,3′‐tetraethyl‐imidacarbocyanine iodide (JC‐1) assay kit (Nanjing, Beyotime, China), as in previous studies from our group (Liu et al., 2016). Cells were placed in 35 mm glass‐bottomed dishes and incubated with JC‐1 (5 μg·mL−1) for 20 min in the dark at 37°C, then washed three times in PBS, and an appropriate volume of Ringer's buffer was added to each dish. Live cell images were then acquired by the Argon laser (488/568 nm) on a confocal microscope (FV500, Olympus, Japan). The JC‐1 was excited at 488 nm, and approximate emission peaks of monomeric and aggregated JC‐1 were 530 nm (green) and 590 nm (red) respectively. Mitochondrial depolarization was quantified by calculating the ratio of monomeric JC‐1 (green fluorescence) to aggregated JC‐1 (red fluorescence).

Mitochondrial isolation and swelling assay

Intact mitochondria were isolated from 2.0 × 107 BASMCs using the ‘Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Cultured Cells’ from Thermo Scientific (Bremen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mitochondrial and the cytosolic fractions were separated. Pore opening was determined by use of a mitochondrial swelling assay (Baines et al., 2005). Briefly, 100 μg isolated mitochondria were resuspended in 200 μL of mitochondria stock solution (120 mmol·L−1 KCl, 10 mmol·L−1 Tris pH 7.6 and 5 mmol·L−1 KH2PO4), and swelling was induced by 50 μmol·L−1 CaCl2 for 30 min. Swelling was promptly monitored as the decrease in 90° light scatter at 540 nm in a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in intact cells

We used an established method for detecting transient mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening in intact cells (Hausenloy et al., 2004). BASMCs were incubated with 1.0 μmol·L−1 calcein‐AM (Invitrogen) and 1.0 mmol·L−1 cobalt chloride (CoCl2; Sigma‐Aldrich), which induced mitochondrial localization of calcein‐AM fluorescence. mPTP opening was measured as a reduction in the mitochondrial calcein signal (shown as a percentage of the baseline value) over six randomly selected areas in three different cells every 5 min for 25 min and captured by an Olympus FV500 confocal laser scanning microscope (emitting at 488 nm and detecting at 505 nm). Calcein‐AM fluorescence was normalized to control.

Immunogold labelling and electron microscopy

Immunogold labelling was detected using a previously described method (Levillain et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2010). Ultrathin sections were incubated in 2% BSA in PBS for 30 min at room temperature to minimize non‐specific binding. The blocking solution was removed, and the grids were incubated at 4°C for 24 h with anti‐TMEM16A (1:10). After the antibody incubation, the grids were rinsed by vigorous agitation in a mixture of 0.5 mol·L−1 NaCl and 0.05% Tween‐20 in 0.1 mol·L−1 phosphate buffer. The sections were incubated at 4°C for 12 h or room temperature for 1 h with 10 nm colloidal gold‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit IgG (Sigma‐Aldrich) at a dilution of 1:5 in blocking solution. They were then washed, counterstained with uranyl acetate and examined under a transmission EM (JEM‐1220; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV accelerating voltage. Anti‐TMEM16A at the same dilution preabsorbed with the immunogenic synthetic peptide was used for the negative controls.

Co‐immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Co‐immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting were performed as described previously (Ma et al., 2016). The cell lysates were incubated with protein G beads for 2 h at 4°C and centrifuged. The supernatants were incubated with cyclophilin D (Millipore), adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT; Cell Signaling Technology) or http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/FamilyDisplayForward?familyId=131 (VDAC; Santa Cruz) antibodies overnight at 4°C. Samples were resolved on 8% SDS‐PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The bound proteins were determined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Data were analysed by densitometry and normalized to the corresponding internal reference.

Data and statistical analysis

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018). Blinded data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All data are expressed as means ± SEM, and the n value represents the number of independent experiments on different batches of cells or different mice. Student's two‐tailed t‐test for independent samples was used to detect significant differences between the two groups. One‐way or two‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons tests were used to compare differences between more than two treatment groups, and the interaction effects in the two‐way ANOVAs were also calculated. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Materials

Cell culture medium (DMEM/F12), FCS, BSA, LipofectAMINE2000 reagent, OPTI‐MEM® I reduced serum medium and cocktail were obtained from Gibco/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=1024, H2O2 and 2,2,2‐tribromoethanol were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies to TMEM16A (ab53212), cyclophilin D (ab110324), and http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2844 (ab692) were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Antibodies to cytochrome c (Cyt‐c) (4272), http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/FamilyDisplayForward?familyId=910 (2772), http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=1625 (9508), http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=1619 (9662), ANT (14671), Cox‐IV (4844), β‐actin (3700) and all secondary antibodies (7074 for anti‐rabbit IgG and 7076 for anti‐mouse IgG) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA). Antibodies tohttp://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/FamilyDisplayForward?familyId=131 VDAC (sc‐390996), protein G beads (sc‐2003) and IgG (sc‐66931 for rabbit IgG and sc‐69786 for mouse IgG) for co‐immunoprecipitation experiments were purchased from Santa Cruz Technology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Other chemicals, unless otherwise specified, were all from Sigma‐Aldrich.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander et al., 2017a,b,c).

Results

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced viability and apoptosis of BASMCs

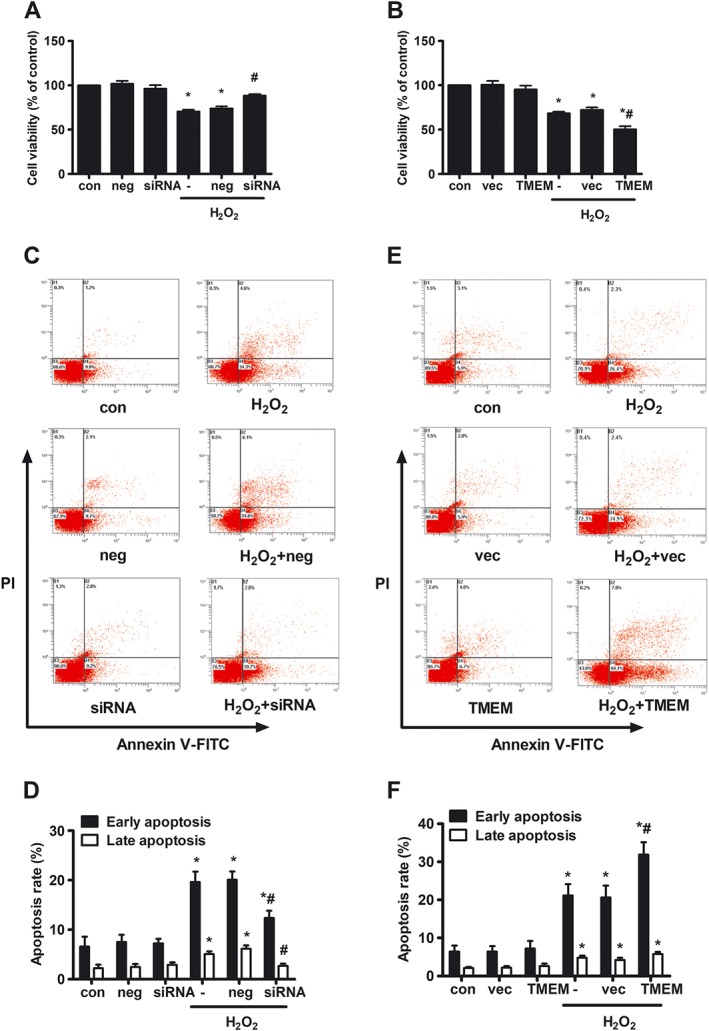

To analyse whether TMEM16A affected H2O2‐induced apoptosis in BASMCs, cell viability was evaluated using the CCK‐8 assay. Upon treatment with 200 μmol·L−1 H2O2 for 24 h, the cell viability rate of BASMCs significantly decreased with 29.5 ± 2.0%, compared with that of the untreated group. TMEM16A siRNA and TMEM16A plasmid transfections were used to decrease and increase TMEM16A protein expression respectively (Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2 for transfection efficiency). Silencing of TMEM16A decreased the reduction of cell viability (Figure 1A), whereas overexpression of TMEM16A further increased the reduction of cell viability (Figure 1B). Negative siRNA or blank vector transfection did not significantly alter the cell viability rate induced by H2O2.

Figure 1.

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced cell viability and apoptosis in BASMCs. Rat BASMCs were treated with 200 μmol·L−1 H2O2 for 24 h. The cell viability was measured by CCK‐8, and apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry (FCM). (A and B) TMEM16A decreased cell viability induced by H2O2 in BASMCs. BASMCs were transfected with (A) TMEM16A siRNA (80 nmol·L−1, siRNA for short) or (B) TMEM16A plasmid (100 ng·μL−1, TMEM for short) and their negative control (neg or vec), respectively, for 24 h followed by 200 μmol·L−1 H2O2 for another 24 h, and cell viability was measured by CCK‐8 (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA). (C–F) TMEM16A potentiated H2O2‐induced cell apoptosis in BASMCs. BASMCs were transfected with (C and D) TMEM16A siRNA or (E and F) TMEM16A plasmid followed by H2O2 as previously described, and cell apoptosis was analysed by Annexin V‐FITC/PI FCM (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

Next, the involvement of TMEM16A in H2O2‐induced BASMC apoptosis was analysed by flow cytometry. Cells were double stained with Annexin V‐FITC and PI. Annexin V could specifically bind with phosphatidylserine located in the surface of cell membrane, whose turnover from the inner side to the outer side of cell membrane is an early sign of apoptosis. PI could specifically bind with DNA, but it could not freely penetrate though healthy cell membrane, otherwise the cell membrane is incomplete, such as cells in the late apoptotic state or in the necrotic state. Therefore, the percentage in the lower right corner represents the early apoptosis rate, and the percentage in the upper right corner represents the late apoptosis rate. The percentage in the lower left corner and the upper left corner represent live rate and necrotic rate respectively. Both early and late apoptosis rates are indicators of the apoptotic state. In BASMCs, treatment with H2O2 induced early and late apoptotic rates of 19.6 ± 2.1 and 5.1 ± 0.6% respectively. Silencing of TMEM16A decreased the early and late apoptotic rate (Figure 1C, D), whereas overexpression of TMEM16A exacerbated the early apoptotic rate without affecting the late apoptotic rate (Figure 1E, F).

Moreover, further experiments revealed that TMEM16A protein expression was not altered by H2O2 treatment in either whole cells or mitochondria (Supporting Information Figure S3A). Furthermore, the four splicing variants of TMEM16A, reported in a previous study (Ferrera et al., 2009), were also not changed by H2O2 treatment in BASMCs (Supporting Information Figure S3B). T16Ainh‐A01 is a selective inhibitor of TMEM16A that can block the CaCC current (Namkung et al., 2011). In this study, T16Ainh‐A01 significantly inhibited apoptotic rate induced by H2O2 (Supporting Information Figure S4). The results above suggest that activation of TMEM16A participates in H2O2‐induced apoptosis in BASMCs.

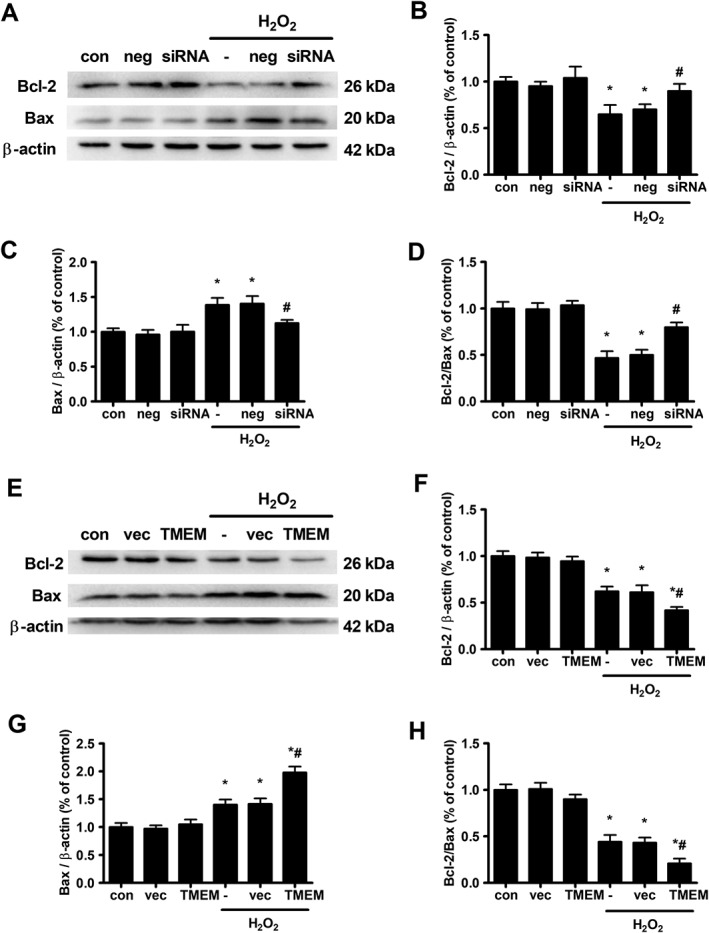

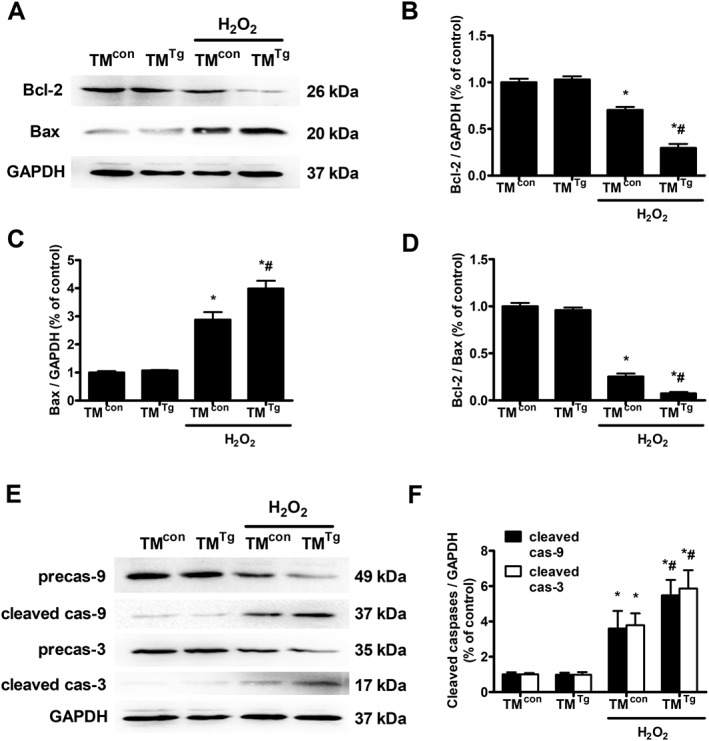

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced Bcl‐2 and Bax expression in BASMCs

The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is regulated by both anti‐apoptotic multidomain proteins of the Bcl‐2 family (such as Bcl‐2, Bcl‐xl and Mcl‐1) as well as by pro‐apoptotic multidomain proteins from the same family (in particular Bax and Bak) (Wang and Youle, 2009). The preset ratio of Bcl‐2/Bax appears to determine survival or death of cells under apoptotic stimulus. The levels of Bcl‐2 and Bax in BASMCs were determined by Western blot. As shown in Figure 2, H2O2 treatment significantly decreased Bcl‐2 protein expression and increased Bax protein expression, resulting in a decrease in the Bcl‐2/Bax ratio. TMEM16A siRNA transfection reversed the effects of H2O2, increased Bcl‐2 and reduced Bax levels, resulting in an increase in Bcl‐2/Bax ratio (Figure 2A–D). In contrast, TMEM16A plasmid transfection further decreased the Bcl‐2/Bax value induced by H2O2, due to the decrease in Bcl‐2 and the increase in Bax levels (Figure 2E–H).

Figure 2.

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced expression of Bcl‐2 and Bax in BASMCs. (A–D) The knockdown of TMEM16A expression reversed H2O2‐induced reduction in Bcl‐2 expression and Bcl‐2/Bax ratio and limited the rise in Bax expression. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA for 24 h, and H2O2 was added for another 24 h. Representative Western blots of the expression of Bcl‐2 and Bax are shown in (A), and densitometric analysis of (B) Bcl‐2 and (C) Bax and the ratio of (D) Bcl‐2/Bax are shown in (B–D). (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA). (E–H) Overexpressing TMEM16A further decreased H2O2‐induced reduction in Bcl‐2 expression and Bcl‐2/Bax ratio and facilitated the rise in Bax expression. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A plasmid for 24 h, and H2O2 was added for another 24 h. Representative Western blots of the expression of Bcl‐2 and Bax are shown in (E), and densitometric analysis of (F) Bcl‐2 and (G) Bax and the ratio of (H) Bcl‐2/Bax are shown in (F–H). (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

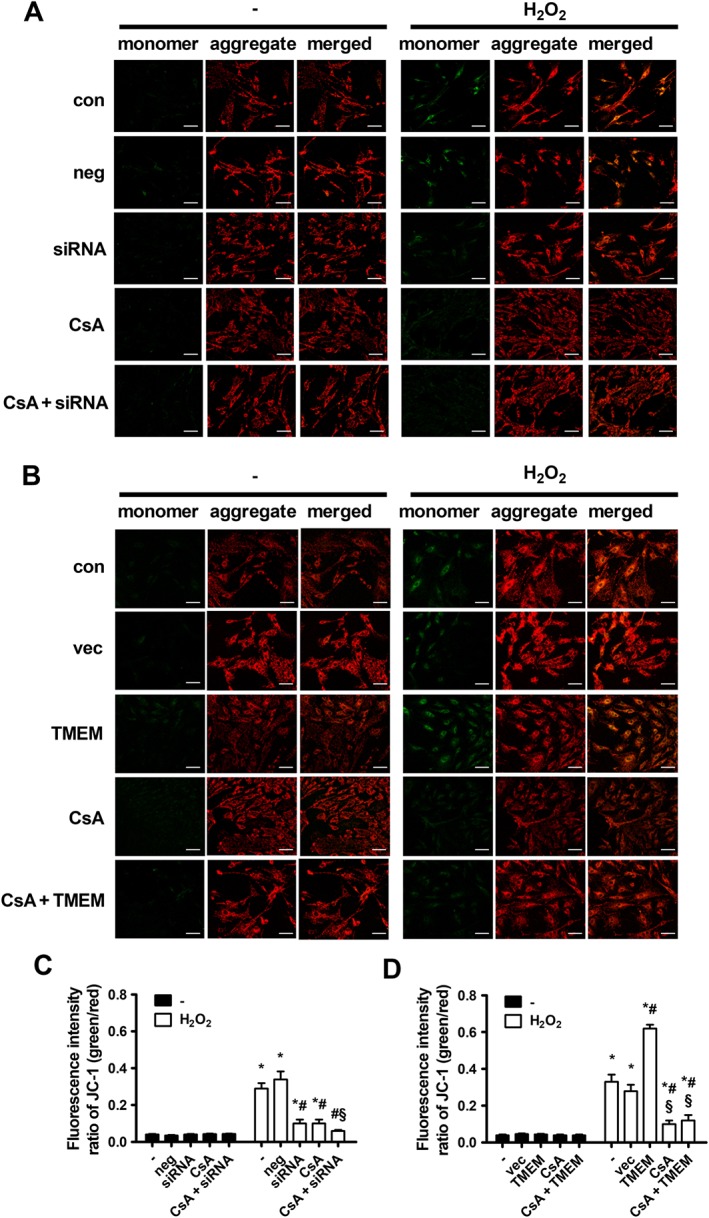

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced mitochondrial membrane depolarization and cytochrome c release

The loss of MMP is a hallmark of early apoptosis and can be a consequence of increased Bax expression (Wang and Youle, 2009). Therefore, we examined MMP alteration using JC‐1 fluorescent dye. JC‐1 is widely used to assess changes in MMP. This dye usually accumulates in mitochondria in aggregates and emits red fluorescence in healthy cells, while the dye flows out into the cytoplasm of apoptotic cells in a monomeric form and emits green fluorescence. Thus, the increase in green/red fluorescence ratio represents loss of MMP. As shown in Figure 3, the increase in green/red fluorescence intensity ratio induced by H2O2 was counteracted and enhanced by transfection with TMEM16A siRNA and TMEM16A plasmid respectively. Notably, cyclosporine A (CsA), an inhibitor of cyclophilin D, which is an important component of the mPTP complex, potentiated the effect of TMEM16A knockdown but reversed the effect of TMEM16A overexpression on MMP.

Figure 3.

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced MMP loss in BASMCs. (A) The knockdown of TMEM16A reversed H2O2‐induced MMP loss, and preincubation with CsA (5 μmol·L−1) 30 min before treatment with H2O2 further restored the MMP level. Representative images of JC‐1‐derived fluorescence in BASMCs with different treatments are shown. Scale bars are 20 μm. (B) Overexpressing TMEM16A potentiated H2O2‐induced MMP loss, and preincubation with CsA (5 μmol·L−1) 30 min before treatment with H2O2 restored the MMP level. Representative images of JC‐1 derived fluorescence in BASMCs with different treatments are shown. Scale bars are 20 μm. (C and D) Mitochondrial depolarization was evaluated by measuring the fluorescence intensity of monomeric JC‐1 (green)/aggregated JC‐1 (red) (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, #P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, § P < 0.05 vs. H2O2 + siRNA or TMEM, respectively, two‐way ANOVA).

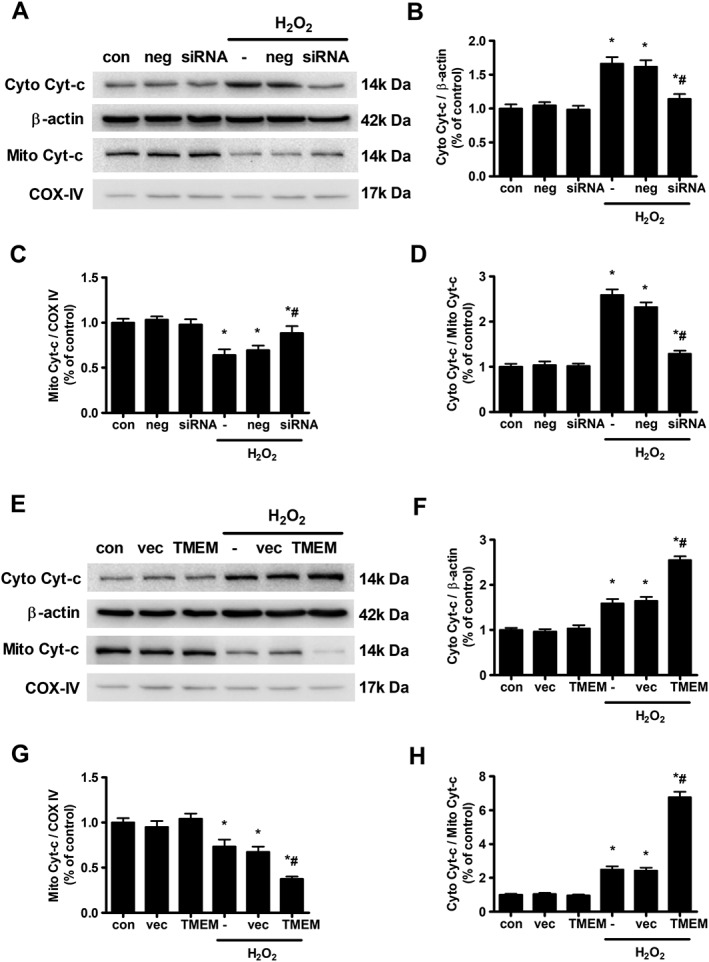

The consequence of MMP loss is the release of Cyt‐c from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm (Wang and Youle, 2009). Figure 4 shows that H2O2 treatment significantly increased the cytoplasmic Cyt‐c level and reduced the mitochondrial Cyt‐c level, resulting in an increase in the Cyt‐c cytoplasmic/mitochondrial ratio. Silencing TMEM16A significantly reduced the ratio (Figure 4A–D), whereas overexpressing TMEM16A further increased this ratio (Figure 4E–H). These results indicate that TMEM16A mediated H2O2‐induced apoptosis by regulating mitochondrial functions.

Figure 4.

Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced mitochondrial Cyt‐c release from the mitochondria (Mito) into the cytoplasm (Cyto) in BASMCs. (A) The knockdown of TMEM16A reduced H2O2‐induced Cyt‐c release. Expression of Cyt‐c in the cytoplasm and mitochondria was examined using Western blot. Cox IV served as loading control of mitochondrial protein. Densitometric analysis of (B) cytoplasm and (C) mitochondrial Cyt‐c expression and (D) the ratio of Cyto Cyt‐c/Mito Cyt‐c (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA). (E) Overexpressing TMEM16A further potentiated H2O2‐induced Cyt‐c release. Expression of Cyt‐c in the cytoplasm and mitochondria was examined using Western blot. Cox IV served as loading control of mitochondrial protein. Densitometric analysis of (F) cytoplasm and (G) mitochondrial Cyt‐c expression and (H) the ratio of Cyto Cyt‐c/Mito Cyt‐c (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

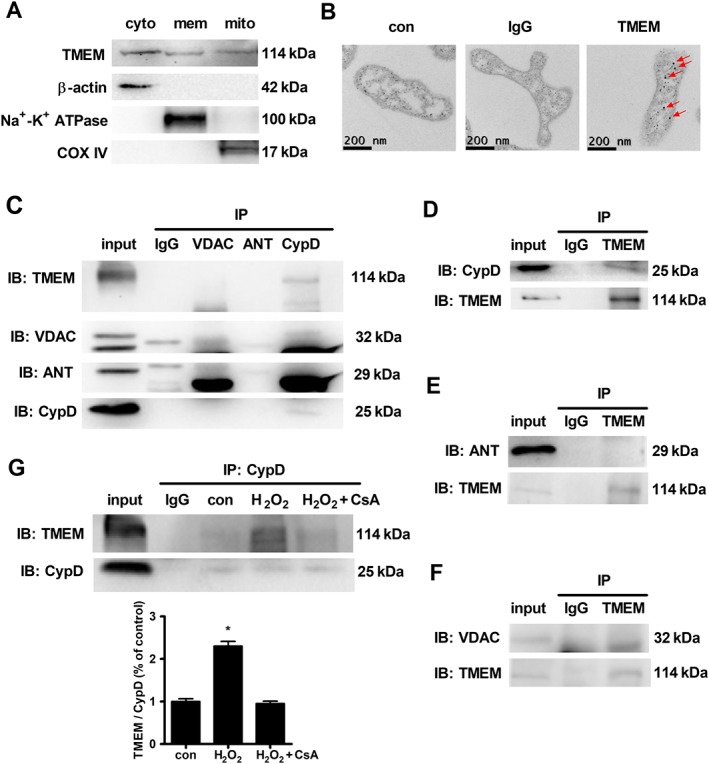

TMEM16A was found to be associated with cyclophilin D in mitochondria

Next, we explored how TMEM16A regulated mitochondrial function. With the purified mitochondrial fraction of BASMCs, the endogenous TMEM16A expression in mitochondria was detected by Western blotting (Figure 5A). The result was further confirmed by immunogold electron microscopy (Figure 5B). The figure shows that TMEM16A is mainly located in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and in the space between the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and IMM. Therefore, we examined whether TMEM16A interacts with components of the mPTP complex, including cyclophilin D, ANT and VDAC. Co‐IP experiments revealed that TMEM16A was immunoprecipitated with cyclophilin D but not with ANT or VDAC (Figure 5C–F). The interaction between TMEM16A and cyclophilin D was up‐regulated by H2O2 but reversed by preincubation with CsA, which inhibits mitochondrial permeability transition by blocking cyclophilin D (Figure 5G), and the protein expression of cyclophilin D was not affected either by silencing or overexpression of TMEM16A (Supporting Information Figure S5).

Figure 5.

TMEM16A was associated with cyclophilin D (CypD) in the mitochondria. (A) Endogenous expression of TMEM16A in the mitochondria was detected in BASMCs by immunoblotting with TMEM16A antibody (n = 6; cyto, mem and mito are cytoplasm, membrane and mitochondria for short). (B) The endogenous TMEM16A expression in mitochondria was detected in BASMCs by immunogold staining with gold‐labelled TMEM16A antibody (see arrows, n = 6). (C–F) Co‐IP showed that cyclophilin D, but not ANT or VDAC, immunoprecipitated with TMEM16A in BASMCs (n = 5). IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot. (G) H2O2 increased the association between TMEM16A and cyclophilin D, which was attenuated by preincubation with CsA (5 μmol·L−1) 30 min before H2O2 treatment (n = 5, * P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA).

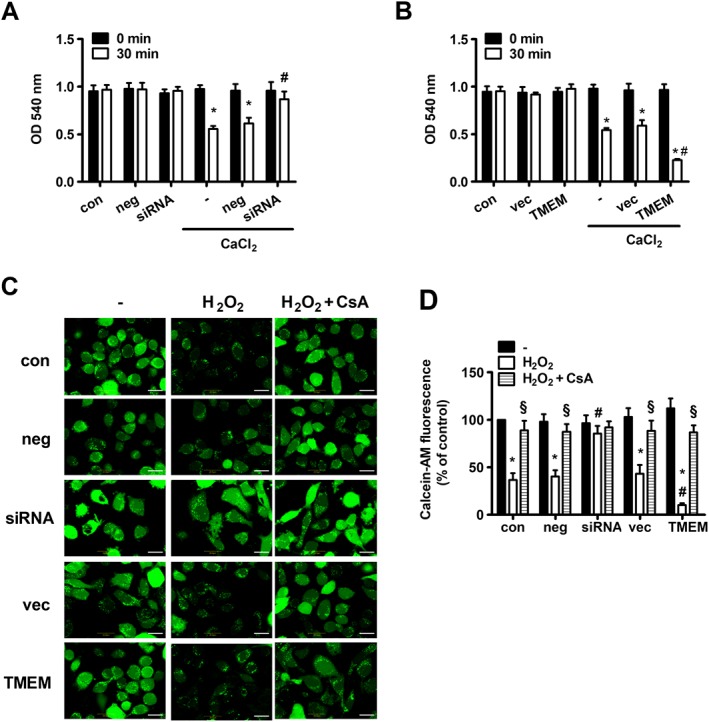

TMEM16A modulated mPTP opening via cyclophilin D

Furthermore, we used the mitochondrial swelling assay, a classical hallmark of mPTP opening, to ascertain whether TMEM16A affects mitochondrial function via mPTP. CaCl2 treatment induced mitochondria swelling, which was inhibited by the silencing of TMEM16A and further promoted by overexpression of TMEM16A (Figure 6A, B). These results were further confirmed by direct in situ assessment of mPTP opening via calcein‐AM, a fluorescent dye that is highly selective for sustained mPTP opening (Figure 6C, D). H2O2 decreased mitochondrial calcein‐AM fluorescence, indicating transient mPTP opening. The fluorescence reduction was abolished or enhanced by transfection with TMEM16A siRNA or TMEM16A plasmid respectively. In addition, the presence of CsA completely blocked the reduction in mitochondrial calcein‐AM fluorescence, suggesting that TMEM16A modulated mPTP opening in a cyclophilin D‐dependent manner.

Figure 6.

Effects of TMEM16A on mPTP opening. (A) TMEM16A knockdown had an inhibitory effect on CaCl2‐induced mitochondria swelling, but (B) TMEM16A overexpression had an opposite effect. Mitochondrial swelling was measured at an OD of 540 nm in normal, TMEM16A silenced and TMEM16A overexpressed BASMCs induced by 50 μmol·L−1 CaCl2 (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con in 30 min, # P < 0.05 vs. CaCl2 in 30 min, two‐way ANOVA). (C and D) H2O2 induced a reduction in mitochondrial calcein‐AM fluorescence, which was reversed by TMEM16A silencing and enhanced by TMEM16A overexpression. Preincubation with CsA (5 μmol·L−1) 30 min before H2O2 treatment completely abolished the effect of H2O2 on mitochondrial calcein‐AM fluorescence. BASMCs were loaded with Calcein‐AM in the presence of CoCl2 and treated with or without 200 μmol·L−1 H2O2 for 8 h. Representative images of Calcein‐AM fluorescence are shown in (C), and the statistical analysis is shown in (D). Scale bars are 10 μm (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con without H2O2, # P < 0.05 vs. con with H2O2, § P < 0.05 vs. respective H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

Effect of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced activation of caspase‐3 and caspase‐9

The opening of mPTP and the subsequent release of cytochrome c led to the activation of caspases, including caspase‐9 and its downstream caspase‐3, which are proteases that cleave key cellular proteins and ultimately induce mitochondria‐dependent apoptosis (Wang and Youle, 2009). As shown in Supporting Information Figure S6, H2O2 treatment significantly increased caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 cleavages, which were significantly attenuated and enhanced by silencing and overexpression of TMEM16A respectively.

In order to further verify the effect of TMEM16A on cell apoptosis, TMTg were used (Supporting Information Figure S7 for genotype and expression identification). The results from TMTg and TMcon BASMCs showed that H2O2 increases Bax and reduces Bcl‐2 expression, resulting in a lower Bcl‐2/Bax ratio and thereby leading to the activation of caspase‐9 and caspase‐3. The above effects were significantly potentiated by TMEM16A overexpression in BASMCs (Figure 7). These data further confirmed that TMEM16A facilitates apoptosis via a mitochondria‐dependent pathway in BASMCs.

Figure 7.

Effects of TMEM16A on Bcl‐2 and Bax expression and on caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 activation, in BASMCs from TMcon and TMTg. (A–D) TMEM16A overexpression further decreased H2O2‐induced reduction in Bcl‐2 expression and Bcl‐2/Bax ratio and facilitated the rise in Bax expression. Representative Western blots of the expression of Bcl‐2 and Bax in mouse BASMCs are shown in (A), and densitometric analysis of (B) Bcl‐2, (C) Bax and the ratio of (D) Bcl‐2/Bax are shown in (B–D) (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA). (E and F) TMEM16A overexpression enhanced H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 (cas‐9) and caspase‐3 (cas‐3) activation in mouse BASMCs. Representative Western blots are shown in (E), and the densitometric analysis is shown in (F) (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

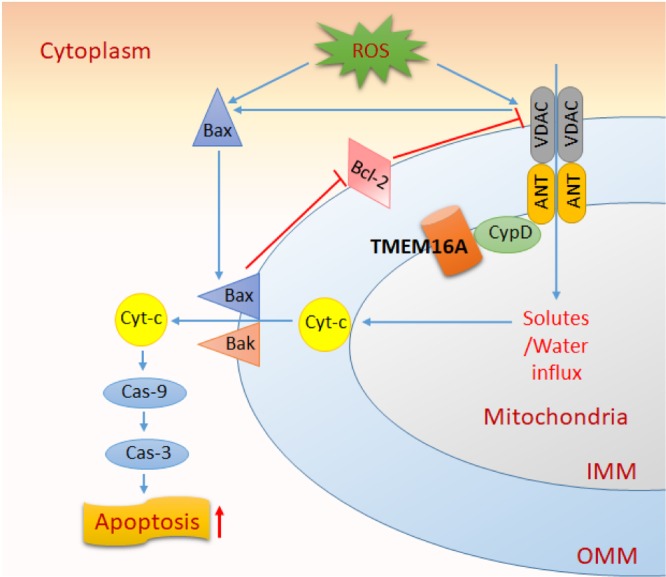

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of TMEM16A in VSMC apoptosis. We found that TMEM16A is involved in H2O2‐induced BASMC apoptosis through a mitochondria‐dependent pathway. Endogenous TMEM16A was found to be expressed in the mitochondria and to modulate mPTP opening in a cyclophilin D‐dependent manner, causing an increase in the translocation of Bax from the cytosol to the mitochondria, and the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytosol, as well as the activation of caspase‐9 and caspase‐3. These results provide compelling evidence that TMEM16A is critically linked to VSMC apoptosis. The schematic drawing of the study is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic drawing of the study. ROS (such as H2O2) increases the translocation of Bax from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria and restrict the inhibitory effect of Bcl‐2 on mPTP opening. The opening of mPTP induces MMP loss and the subsequent OMM rupture, in combination with an increased interaction of Bax and Bak in OMM, and it also facilitates Cyt‐c release from the space between OMM and IMM to the cytoplasm. Finally, the opening of mPTP initiates the cleavage of caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 and progresses to apoptosis. mPTP consists of VDAC, ANT and cyclophilin D. TMEM16A is located in the IMM and associates with cyclophilin D but not with ANT or VDAC. This interaction participates in H2O2‐induced mitochondria‐dependent apoptosis.

In 2008, three independent laboratories reported that TMEM16A encodes CaCC (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008). Later, a growing number of studies using knockout mice or RNA silencing technology demonstrated that TMEM16A constitutes the native CaCCs in various cells, including epithelial cells (Huang et al., 2012), sensory neurons (Liu et al., 2010), the kidney (Buchholz et al., 2014), the heart (El et al., 2014), vascular endothelial cells (Ma et al., 2017) and vascular smooth muscle cells (Manoury et al., 2010). TMEM16A is located within the 11q13 amplicon, which is suggested to be a potential ‘driver’ of oncogenesis as well of proliferation and apoptosis (Wilkerson and Reis‐Filho, 2013). CaCC is involved in the regulation of proliferation. However, studies indicate that the expression and the function of TMEM16A vary across cell types and thus may greatly influence experimental results. For example, the protein level and the activity of TMEM16A negatively correlate with VSMC proliferation (Wang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015), but these correlations were found to be positive in epithelial cells (Ruffin et al., 2013; Buchholz et al., 2014; Cha et al., 2015) and tumour cells (Britschgi et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2016). Unlike the role of TMEM16A in cell proliferation, which has been fully explored in various cell types, the effect of TMEM16A on cell apoptosis has only been reported for tumour cells (Britschgi et al., 2013; Berglund et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2015; Deng et al., 2016) and ECs (Allawzi et al., 2018). In this study, we provided evidence that TMEM16A contributes to VSMC apoptosis, and the results were also opposite to those of tumour cells. These contradictory observations may be related with differences in cell types, apoptotic stimuli and channel profiles. In addition, a previous work revealed four different splicing variants of TMEM16A in VSMCs (Manoury et al., 2010). Therefore, the differences in expression levels, location and function of these variants (Ferrera et al., 2009) also might explain the opposite effects of apoptosis on BASMCs and tumour cells.

H2O2 superoxide and hydroxyl radicals are major ROS that play a key role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, hypertension, stroke, diabetes and cancer (Bedard and Krause, 2007). H2O2 is more stable than other ROS and easily penetrates the cell membrane. Hence, it is widely used as a rapid and sensitive oxidative stress‐induced apoptotic model (Qian et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2013; Zeng et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). It has been well established that excessive H2O2 triggers the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, leading to apoptosis (Redza‐Dutordoir and Averill‐Bates, 2016). Pro‐apoptotic proteins, such as Bax, translocate to the OMM and alleviate the inhibitory effects of anti‐apoptotic survival proteins, such as Bcl‐2, in conditions of oxidative stress. This process facilitates OMM permeabilization by forming mPTP complex, resulting in the leakage of pro‐apoptotic factors, such as Cyt‐c into the cytosol. As soon as Cyt‐c is released from the mitochondria to the cytosol, caspase‐9 is activated, which in turn activates the executioners caspase‐3, ‐6 and ‐7 and ultimately leads to apoptosis (Wang and Youle, 2009; Redza‐Dutordoir and Averill‐Bates, 2016). In the present study, the overexpression of TMEM16A further potentiated H2O2‐induced apoptosis via a mitochondrial pathway as described above, whereas silencing of TMEM16A exerted an opposite effect, suggesting that TMEM16A is a potential regulator of apoptosis in VSMCs.

Mitochondria play an important role in triggering and regulating apoptosis. In this study, we used immunoblotting and immunogold staining to prove the presence of endogenous TMEM16A expression in mitochondria. This result is consistent with a previous study in endothelial cells (Allawzi et al., 2018). Moreover, we explored the intrinsic mechanism of TMEM16A on mitochondrial function. The mPTP complex is crucial for the regulation of mitochondrial permeability, whose molecular nature remains to be elucidated. Previously, the mPTP complex was thought to be composed of cyclophilin D, ANT and VDAC (Galluzzi et al., 2012). Co‐IP in this study showed that cyclophilin D, but not ANT or VDAC, immunoprecipitated with TMEM16A, and further study showed that TMEM16A modulated mPTP opening in a cyclophilin D‐dependent manner. The matrix protein cyclophilin D is a peptidylprolyl cis–trans isomerase that regulates mitochondrial permeability transition, resulting in the subsequent effects on cardiovascular physiology and pathology (Elrod and Molkentin, 2013). In cyclophilin D knockout mice, it proved to have protective actions in numerous ischaemia–reperfusion injury models in various organs, including the heart (Baines et al., 2005), the brain (Schinzel et al., 2005) and the kidney (Devalaraja‐Narashimha et al., 2009). On the contrary, a recent work showed a progressively worse cardiac function in cyclophilin D knockout mice under pressure overload‐induced heart failure (Elrod et al., 2010). Therefore, cyclophilin D plays different roles in cardiovascular diseases, and the use of cyclophilin D inhibitors, as well as of TMEM16A inhibitors, is needed to evaluate cardiac functions in future clinical application.

It is noteworthy to mention that H2O2 treatment did not alter the protein expression of TMEM16A in whole cell or in the mitochondria, and the four splicing variants of TMEM16A did not change under H2O2 stimulation. Therefore, the effect of TMEM16A on apoptosis might be mediated by protein interaction or by a change in channel activity but not by a change in protein expression. We demonstrated that among the three components of mPTP complex, TMEM16A interacts with cyclophilin D, suggesting that protein interaction may play a role in apoptosis. However, TMEM16A does not bind ANT or VDAC, probably due to the different distribution of these proteins. cyclophilin D is a molecule of the mitochondrial matrix that can translocate and bind to ANT in the IMM and to VDAC in the OMM. In this study, we noticed that TMEM16A is mainly located in IMM and in the space between OMM and IMM (Figure 5B); thus, it might be helpful to induce the movement of cyclophilin D towards IMM thereby leading to its subsequent association with ANT. A similar result was also observed in a previous study showing that http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2030 directly interacts with cyclophilin D but not with ANT or VDAC (Xi et al., 2009). Recently, experiments in VDAC and ANT knockout mice have shown that neither VDAC nor ANT is a component of mPTP (Kokoszka et al., 2004; Baines et al., 2007). The underlying composition of mPTP is still unclear. This might explain why TMEM16A only interacted with cyclophilin D. Therefore, the general role of TMEM16A as regulator of mitochondrial protein activity remains an unsolved area.

TMEM16A has been identified to encode CaCC by whole‐cell patch clamp in cell membrane. However, the question remains as to whether TMEM16A modulates mitochondrial functions in a CaCC‐dependent manner. Although T16Ainh‐A01, a specific inhibitor of TMEM16A that can block CaCC current, alleviated H2O2‐induced apoptosis, suggesting that activation of TMEM16A also plays a role in H2O2‐induced apoptosis. Further studies using patch‐clamp recording of mitoplasts should address this question in the future.

In the present study, we used vascular smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice in order to further verify our findings, and the results from mouse BASMCs were consistent with those in cultured rat BASMCs, suggesting that targeting TMEM16A might be a useful therapy to prevent vascular apoptosis. Currently, it is difficult to target mitochondrial TMEM16A alone, as TMEM16A expression is broad and has many cellular effects (Pedemonte and Galietta, 2014). At least, this study might provide an approach for the treatment of vascular remodelling‐related diseases, such as stroke and atherosclerosis, via regulating the balance between proliferation and apoptosis. Moreover, this study may shed a new light on the development of tissue‐specific or even organelle‐specific targeted TMEM16A inhibitors.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings established TMEM16A as a pro‐apoptotic factor via modulation of mitochondrial membrane permeability in a cyclophilin D‐dependent manner, highlight the importance of TMEM16A Cl− channels for apoptosis in VSMCs and provide mechanistic insights into their role in vascular remodelling. Most importantly, our study opens up potential opportunities for therapeutic intervention in several remodelling‐prevalent diseases, such as hypertension, stroke, aortic aneurysm and arteriosclerosis.

Author contributions

J.‐W.Z. and B.‐Y.C. performed the animal experiments, immunogold labelling and Western blots. X.‐F.L. carried out the cell culture and transfection. L.S. performed the flow cytometry. X.‐L.Z. performed the mitochondrial swelling assay. H.‐Q.Z. carried out the animal feeding. Y.‐H.D. and G.‐L.W. carried out the data analysis. M.‐M.M. and Y.‐Y.G. conceived the study and drafted the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.13405/abstract acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Table S1 Primers of TMEM16A splicing variants.

Figure S1 Effect of TMEM16A siRNA transfection on the expression of TMEM16A in basilar artery smooth muscle cells (BASMCs). A. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA in different concentration for 48 h. Western blot showed that the dose of 80 nmol·L−1 was suitable for silencing TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, oneway ANOVA). B. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA in dose of 80 nmol·L−1 for different time course. Western blot showed that the time course of 48 h was suitable for silencing of TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA).

Figure S2 Effect of TMEM16A plasmid transfection on the expression of TMEM16A in BASMCs. A. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A plasmid tagged with RFP in different concentration for 48 h. Western blot with anti‐RFP primary antibody showed that the dose of 100 ng·μL−1 was suitable for overexpressing TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA). B. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A plasmid in the dose of 100 ng·μL−1 for different time course. Western blot showed that the time course of 48 h was suitable for overexpressing TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA).

Figure S3 The effect of H2O2 (200 μmol·L−1, 24 h) on TMEM16A protein and splicing variants mRNA expression in BASMCs. A The protein expression of TMEM16A was not changed in either whole‐cell or in the mitochondria under the stimulation of H2O2. Cell and mito are abbreviations of the whole‐cell and the mitochondria, respectively (n = 4, 2‐tailed Student's t test). B. The mRNA expression of TMEM16A splicing variants were not changed under the stimulation of H2O2 (n = 4, 2‐tailed Student's t test).

Figure S4 Effect of T16Ainh‐A01 (T16Ainh) on H2O2 (200 μmol·L−1, 24 h)‐induced apoptosis in BASMCs. T16Ainh‐A01 (10 μmol·L−1) was added 30 min before H2O2‐treatment. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry. (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

Figure S5 The effect of TMEM16A on cyclophilin D (CypD) expression in BASMCs. A and B. The expression of CypD was not affected by TMEM16A silencing (A) or overexpressing (B). Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA or TMEM16A plasmid for 24 h and added H2O2 for additional 24 h. The expression of CypD was measured by western blot (n = 6, two‐way ANOVA).

Figure S6 Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 (cas‐9) and caspase‐3 (cas‐3) activation. A and B. TMEM16A knockdown reversed H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 activation in BASMCs. Representative western blots are shown in A, and the densitometric analysis is shown in B (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, #P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA). C and D. TMEM16A overexpression enhanced H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 activation. Representative western blots are shown in C, and the densitometric analysis is shown in D (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, #P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

Figure S7 Identification of smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice (TMTg). A. Mice were identified by PCR amplified from genomic DNA using primers specific for transgene‐TMEM16A and Tagln‐Cre, respectively. Mice containing transgene‐TMEM16A and Tagln ‐Cre were considered as TMTg. Mice containing transgene‐TMEM16A, but not Tagln ‐Cre were considered as TMcon. B. The protein expression of TMEM16A was successfully increased in the primary cultured BASMCs isolated from TMTg compared with that from TMcon (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, 2‐tailed Student's t test). C. The protein expression of TMEM16A was comparable in other tissues, including heart, liver, kidney, and brain from TMcon and TMTg (n = 5, 2‐tailed Student's t test).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (key grant nos. 81230082, 81773721 and 81773722), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (nos. 2014A030310102 and 2014A030313087), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou City (no. 201607010255), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 17ykzd02) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2015A030302012).

Zeng, J.‐W. , Chen, B.‐Y. , Lv, X.‐F. , Sun, L. , Zeng, X.‐L. , Zheng, H.‐Q. , Du, Y.‐H. , Wang, G.‐L. , Ma, M.‐M. , and Guan, Y.‐Y. (2018) Transmembrane member 16A participates in hydrogen peroxide‐induced apoptosis by facilitating mitochondria‐dependent pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175: 3669–3684. 10.1111/bph.14432.

Contributor Information

Ming‐Ming Ma, Email: mamm3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yong‐Yuan Guan, Email: guanyy@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E et al (2017a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 174: S272–S359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E, Harding SD et al (2017b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Overview. Br J Pharmacol 174: S1–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E, Harding SD et al (2017c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: other ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 174: S195–S207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allawzi AM, Vang A, Clements RT, Jhun BS, Kue NR, Mancini TJ et al (2018). Activation of anoctamin‐1 limits pulmonary endothelial cell proliferation via p38‐mitogen‐activated protein kinase‐dependent apoptosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 58: 658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Purcell NH, Blair NS, Osinska H, Hambleton MA et al (2005). Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature 434: 658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Sheiko T, Craigen WJ, Molkentin JD (2007). Voltage‐dependent anion channels are dispensable for mitochondrial‐dependent cell death. Nat Cell Biol 9: 550–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard K, Krause KH (2007). The NOX family of ROS‐generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87: 245–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund E, Akcakaya P, Berglund D, Karlsson F, Vukojevic V, Lee L et al (2014). Functional role of the Ca2+‐activated Cl− channel DOG1/TMEM16A in gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells. Exp Cell Res 326: 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britschgi A, Bill A, Brinkhaus H, Rothwell C, Clay I, Duss S et al (2013). Calcium‐activated chloride channel ANO1 promotes breast cancer progression by activating EGFR and CAMK signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: E1026–E1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz B, Faria D, Schley G, Schreiber R, Eckardt KU, Kunzelmann K (2014). Anoctamin 1 induces calcium‐activated chloride secretion and proliferation of renal cyst‐forming epithelial cells. Kidney Int 85: 1058–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulley S, Neeb ZP, Burris SK, Bannister JP, Thomas‐Gatewood CM, Jangsangthong W et al (2012). TMEM16A/ANO1 channels contribute to the myogenic response in cerebral arteries. Circ Res 111: 1027–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E et al (2008). TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium‐dependent chloride channel activity. Science 322: 590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JY, Wee J, Jung J, Jang Y, Lee B, Hong GS et al (2015). Anoctamin 1 (TMEM16A) is essential for testosterone‐induced prostate hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 9722–9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Alexander S, Cirino G, Docherty JR, George CH, Giembycz MA et al (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. Br J Pharmacol 175: 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam VS, Boedtkjer DM, Nyvad J, Aalkjaer C, Matchkov V (2013). TMEM16A knockdown abrogates two different Ca‐activated Cl currents and contractility of smooth muscle in rat mesenteric small arteries. Pflugers Arch 466: 1391–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Yang J, Chen H, Ma B, Pan K, Su C et al (2016). Knockdown of TMEM16A suppressed MAPK and inhibited cell proliferation and migration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 9: 325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalaraja‐Narashimha K, Diener AM, Padanilam BJ (2009). Cyclophilin D gene ablation protects mice from ischemic renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F749–F759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El CA, Norez C, Magaud C, Bescond J, Chatelier A, Fares N et al (2014). ANO1 contributes to angiotensin‐II‐activated Ca2+‐dependent Cl− current in human atrial fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 68: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod JW, Molkentin JD (2013). Physiologic functions of cyclophilin D and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Circ J 77: 1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod JW, Wong R, Mishra S, Vagnozzi RJ, Sakthievel B, Goonasekera SA et al (2010). Cyclophilin D controls mitochondrial pore‐dependent Ca2+ exchange, metabolic flexibility, and propensity for heart failure in mice. J Clin Investig 120: 3680–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L, Caputo A, Ubby I, Bussani E, Zegarra‐Moran O, Ravazzolo R et al (2009). Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem 284: 33360–33368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Trojel‐Hansen C, Kroemer G (2012). Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and death. Circ Res 111: 1198–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbanov E, Shiliang X (2006). The key role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 30: 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, Southan C, Pawson AJ, Ireland S et al (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res 46: D1091–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausenloy D, Wynne A, Duchen M, Yellon D (2004). Transient mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening mediates preconditioning‐induced protection. Circulation 109: 1714–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze C, Seniuk A, Sokolov MV, Huebner AK, Klementowicz AE, Szijarto IA et al (2014). Disruption of vascular Ca2+‐activated chloride currents lowers blood pressure. J Clin Investig 124: 675–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Zhang H, Wu M, Yang H, Kudo M, Peters CJ et al (2012). Calcium‐activated chloride channel TMEM16A modulates mucin secretion and airway smooth muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 16354–16359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Liu Y, Ma MM, Tang YB, Zhou JG, Guan YY (2013). Mitochondria dependent pathway is involved in the protective effect of bestrophin‐3 on hydrogen peroxide‐induced apoptosis in basilar artery smooth muscle cells. Apoptosis 18: 556–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszka JE, Waymire KG, Levy SE, Sligh JE, Cai J, Jones DP et al (2004). The ADP/ATP translocator is not essential for the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Nature 427: 461–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratskyi A, Kondratska K, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N (2015). Ion channels in the regulation of apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1848: 2532–2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kang S, Lee SG, Jin JH, Park JW, Park SM et al (2010). Fibrillar superstructure formation of hemoglobin A and its conductive, photodynamic and photovoltaic effects. Acta Biomater 6: 4689–4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levillain O, Balvay S, Peyrol S (2005). Mitochondrial expression of arginase II in male and female rat inner medullary collecting ducts. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 53: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RS, Wang Y, Chen HS, Jiang FY, Tu Q, Li WJ et al (2016). TMEM16A contributes to angiotensin II‐induced cerebral vasoconstriction via the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 13: 3691–3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Linley JE, Du X, Zhang X, Ooi L, Zhang H et al (2010). The acute nociceptive signals induced by bradykinin in rat sensory neurons are mediated by inhibition of M‐type K+ channels and activation of Ca2+‐activated Cl− channels. J Clin Investig 120: 1240–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Gao M, Ma MM, Tang YB, Zhou JG, Wang GL et al (2016). Endophilin A2 protects HO‐induced apoptosis by blockade of Bax translocation in rat basilar artery smooth muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 92: 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma MM, Gao M, Guo KM, Wang M, Li XY, Zeng XL et al (2017). TMEM16A contributes to endothelial dysfunction by facilitating Nox2 NADPH oxidase‐derived reactive oxygen species generation in hypertension. Hypertension 69: 892–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma MM, Lin CX, Liu CZ, Gao M, Sun L, Tang YB et al (2016). Threonine532 phosphorylation in ClC‐3 channels is required for angiotensin II‐induced Cl− current and migration in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 173: 529–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Tamuleviciute A, Tammaro P (2010). TMEM16A/anoctamin 1 protein mediates calcium‐activated chloride currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 588: 2305–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung W, Phuan PW, Verkman AS (2011). TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium‐activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 286: 2365–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedemonte N, Galietta LJ (2014). Structure and function of TMEM16 proteins (anoctamins). Physiol Rev 94: 419–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Du YH, Tang YB, Lv XF, Liu J, Zhou JG et al (2011). ClC‐3 chloride channel prevents apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide in basilar artery smooth muscle cells through mitochondria dependent pathway. Apoptosis 16: 468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redza‐Dutordoir M, Averill‐Bates DA (2016). Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863: 2977–2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffin M, Voland M, Marie S, Bonora M, Blanchard E, Blouquit‐Laye S et al (2013). Anoctamin 1 dysregulation alters bronchial epithelial repair in cystic fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832: 2340–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinzel AC, Takeuchi O, Huang Z, Fisher JK, Zhou Z, Rubens J et al (2005). Cyclophilin D is a component of mitochondrial permeability transition and mediates neuronal cell death after focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 12005–12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY (2008). Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium‐activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 134: 1019–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull CM, Tabas I (2011). Mechanisms of ER stress‐induced apoptosis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2792–2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y, Park J, Kim M, Lee HK, Kim JH, Jeong JH et al (2015). Inhibition of ANO1/TMEM16A chloride channel by idebenone and its cytotoxicity to cancer cell lines. PLoS One 10: e133656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Xia Y, Paudel O, Yang XR, Sham JS (2012). Chronic hypoxia‐induced upregulation of Ca2+‐activated Cl− channel in pulmonary arterial myocytes: a mechanism contributing to enhanced vasoreactivity. J Physiol 590: 3507–3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li C, Huai R, Qu Z (2015). Overexpression of ANO1/TMEM16A, an arterial Ca2+‐activated Cl− channel, contributes to spontaneous hypertension. J Mol Cell Cardiol 82: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Youle RJ (2009). The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Annu Rev Genet 43: 95–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Yang H, Zheng LY, Zhang Z, Tang YB, Wang GL et al (2012). Downregulation of TMEM16A calcium‐activated chloride channel contributes to cerebrovascular remodeling during hypertension by promoting basilar smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation 125: 697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Leo MD, Narayanan D, Kuruvilla KP, Jaggar JH (2016). Local coupling of TRPC6 to ANO1/TMEM16A channels in smooth muscle cells amplifies vasoconstriction in cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 310: C1001–C1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanitchakool P, Ousingsawat J, Sirianant L, MacAulay N, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K (2016). Cl− channels in apoptosis. Eur Biophys J 45: 599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson PM, Reis‐Filho JS (2013). The 11q13‐q14 amplicon: clinicopathological correlations and potential drivers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 52: 333–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi J, Wang H, Mueller RA, Norfleet EA, Xu Z (2009). Mechanism for resveratrol‐induced cardioprotection against reperfusion injury involves glycogen synthase kinase 3β and mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Eur J Pharmacol 604: 111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS et al (2008). TMEM16A confers receptor‐activated calcium‐dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455: 1210–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z, Wu MM, Wang CY, Li YC, Yu CJ, Gong YF et al (2015). Characterization of cardiac anoctamin1 Ca2+‐activated chloride channels and functional role in ischemia‐induced arrhythmias. J Cell Physiol 230: 337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng JW, Zeng XL, Li FY, Ma MM, Yuan F, Liu J et al (2014). Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) prevents apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide in basilar artery smooth muscle cells. Apoptosis 19: 1317–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XH, Zheng B, Yang Z, He M, Yue LY, Zhang RN et al (2015). TMEM16A and myocardin form a positive feedback loop that is disrupted by KLF5 during Ang II‐induced vascular remodeling. Hypertension 66: 412–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Primers of TMEM16A splicing variants.

Figure S1 Effect of TMEM16A siRNA transfection on the expression of TMEM16A in basilar artery smooth muscle cells (BASMCs). A. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA in different concentration for 48 h. Western blot showed that the dose of 80 nmol·L−1 was suitable for silencing TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, oneway ANOVA). B. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA in dose of 80 nmol·L−1 for different time course. Western blot showed that the time course of 48 h was suitable for silencing of TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA).

Figure S2 Effect of TMEM16A plasmid transfection on the expression of TMEM16A in BASMCs. A. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A plasmid tagged with RFP in different concentration for 48 h. Western blot with anti‐RFP primary antibody showed that the dose of 100 ng·μL−1 was suitable for overexpressing TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA). B. Cells were transfected with TMEM16A plasmid in the dose of 100 ng·μL−1 for different time course. Western blot showed that the time course of 48 h was suitable for overexpressing TMEM16A (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, one‐way ANOVA).

Figure S3 The effect of H2O2 (200 μmol·L−1, 24 h) on TMEM16A protein and splicing variants mRNA expression in BASMCs. A The protein expression of TMEM16A was not changed in either whole‐cell or in the mitochondria under the stimulation of H2O2. Cell and mito are abbreviations of the whole‐cell and the mitochondria, respectively (n = 4, 2‐tailed Student's t test). B. The mRNA expression of TMEM16A splicing variants were not changed under the stimulation of H2O2 (n = 4, 2‐tailed Student's t test).

Figure S4 Effect of T16Ainh‐A01 (T16Ainh) on H2O2 (200 μmol·L−1, 24 h)‐induced apoptosis in BASMCs. T16Ainh‐A01 (10 μmol·L−1) was added 30 min before H2O2‐treatment. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry. (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, # P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

Figure S5 The effect of TMEM16A on cyclophilin D (CypD) expression in BASMCs. A and B. The expression of CypD was not affected by TMEM16A silencing (A) or overexpressing (B). Cells were transfected with TMEM16A siRNA or TMEM16A plasmid for 24 h and added H2O2 for additional 24 h. The expression of CypD was measured by western blot (n = 6, two‐way ANOVA).

Figure S6 Effects of TMEM16A on H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 (cas‐9) and caspase‐3 (cas‐3) activation. A and B. TMEM16A knockdown reversed H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 activation in BASMCs. Representative western blots are shown in A, and the densitometric analysis is shown in B (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, #P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA). C and D. TMEM16A overexpression enhanced H2O2‐induced caspase‐9 and caspase‐3 activation. Representative western blots are shown in C, and the densitometric analysis is shown in D (n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. con, #P < 0.05 vs. H2O2, two‐way ANOVA).

Figure S7 Identification of smooth muscle‐specific TMEM16A transgenic mice (TMTg). A. Mice were identified by PCR amplified from genomic DNA using primers specific for transgene‐TMEM16A and Tagln‐Cre, respectively. Mice containing transgene‐TMEM16A and Tagln ‐Cre were considered as TMTg. Mice containing transgene‐TMEM16A, but not Tagln ‐Cre were considered as TMcon. B. The protein expression of TMEM16A was successfully increased in the primary cultured BASMCs isolated from TMTg compared with that from TMcon (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. con, 2‐tailed Student's t test). C. The protein expression of TMEM16A was comparable in other tissues, including heart, liver, kidney, and brain from TMcon and TMTg (n = 5, 2‐tailed Student's t test).