Abstract

Photobiomodulation (PBM) has been demonstrated as a neuroprotective strategy, but its effect on perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy is still unknown. The current study was designed to shed light on the potential beneficial effect of PBM on neonatal brain injury induced by hypoxia ischemia (HI) in a rat model. Postnatal rats were subjected to hypoxic-ischemic insult, followed by 7-day PBM treatment via a continuous wave diode laser with a wavelength of 808 nm. We demonstrated that PBM treatment significantly reduced HI-induced brain lesion in both the cortex and hippocampal CA1 subregion. Molecular studies indicated that PBM treatment profoundly restored mitochondrial dynamics by suppressing HI induced mitochondrial fragmentation. Further investigation of mitochondrial function revealed that PBM treatment remarkably attenuated mitochondrial membrane collapse, accompanied with enhanced ATP synthesis in neonatal HI rats. In addition, PBM treatment led to robust inhibition of oxidative damage, manifested by significant reduction in the productions of 4-HNE, P-H2AX (S139), malondialdehyde (MDA), as well as protein carbonyls. Finally, PBM treatment suppressed the activation of mitochondria-dependent neuronal apoptosis in HI rats, as evidenced by decreased pro-apoptotic cascade 3/9 and TUNEL-positive neurons. Taken together, our findings demonstrated that PBM treatment contributed to a robust neuroprotection via the attenuation of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and final neuronal apoptosis in the neonatal HI brain.

Keywords: Photobiomodulation therapy, Neonatal hypoxic-ischemia, Apoptosis, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Oxidative stress

Introduction

Occurring in ~0.4% of live births and presenting a mortality rate of 20%, neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in newborn infants (Colver et al., 2014; Juul and Ferriero, 2014), occurring most commonly in premature infants (Vannucci and Hagberg, 2004). Hypoxic ischemia (HI) commences during birth or in the early perinatal period with a reduction or cessation cerebral blood flow, resulting in hypoxic brain injury that causes white matter necrotic lesions and dispersed grey matter apoptosis (Blomgren and Hagberg, 2006). The damage left in the wake of neonatal HI contributes heavily to infant mortality, as well as several motor and developmental disorders that generally persist throughout adulthood. The most well-known of these conditions is spastic cerebral palsy, a disabling condition characterized by physical disability and long term developmental difficulties, of which HIE is the primary cause. In mild to moderate cases, however, HI damage may manifest in adolescence as cognitive, attentional, and behavioral disturbances that appear seemingly without cause (Blomgren and Hagberg, 2006; Semple et al., 2013). This is of particular significance, as modern developments in postnatal healthcare have decreased incidence of the most severe cases, whereas mild to moderate cases occur with startling frequency (Smith et al., 2000). HIE is heavily associated with low birth weight and demands immediate postnatal intensive care (Vannucci and Hagberg, 2004). Compounding this problem is the stark lack of effective therapeutic options that can slow the advance of ischemic injury in the neonatal brain.

In many ways, the neonatal ischemic response reflects that of the mature brain. Reduced O2 levels decrease aerobic respiration, causing a sharp decline in neuronal ATP levels. Without the ATP required for maintenance of the resting neuronal transmembrane potential, widespread depolarization occurs, triggering widespread excessive glutamate release (Vannucci and Hagberg, 2004; Thornton et al., 2012). This released glutamate acts on receptors of post-synaptic cells, triggering excessive firing that strengthens inappropriate circuits, potentially leading to long lasting pathologies of severe epilepsy due to developmental upregulation of NMDA receptor subunits (Vannucci and Hagberg, 2004; Semple et al., 2013). Glutamatergic excitatory signaling initiates rapid over-influx of Ca2+, contributing to activation of mitochondrial apoptosis pathways (Thornton et al., 2012). Alongside this, Ca2+ influx triggers cellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that initiate cellular damage in HI (Blomgren and Hagberg, 2006). Peroxynitrite, in particular, causes excessive lipid peroxidation that contributes significantly to the pathology of HI injury, especially damage to immature oligodendrocytes and their progenitors (Blomgren and Hagberg, 2006). This contributes to and is simultaneously exacerbated by developing mitochondrial damage, resulting in sporadic cell death, particularly in sensitive and developmentally critical pools of neural progenitor cells (Vannucci and Hagberg, 2004). These insults impact the population, proliferation, and differentiation of these cells, resulting in impaired development with repercussions lasting a lifetime (Semple et al., 2013; Rumajogee et al., 2016). As well, this damage particularly affects neuronal mitochondria, damages which underlie the pathophysiology of neonatal HI damage.

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that play vital roles in oxidative energy metabolism and cellular signaling. During the process of oxidative phosphorylation that produces critical cellular ATP, the mitochondria shuttle highly-energetic electrons from food substrates along a series of protein complexes, the electron transfer chain (ETC). Blockade of this process leads to electron leakage that produces dangerous free radicals which damage mitochondrial components, initiating a self-perpetuating cycle that prolongs the impact of the initial insult over an extended duration (Akbar et al., 2016; Ham and Raju, 2017). The dysfunction can translate into long term deficits in mitochondrial function and energy production (Akbar et al., 2016). In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction disrupts the mitochondrial dynamics that mitochondria rely on, resulting in widespread mitochondrial fragmentation. Mitochondrial fission and fusion events, referred to as mitochondrial dynamics, maintain function via repair and mitochondrial quality control, with fusion events facilitating sharing of mitochondrial components, and fission allowing for mitophagy of poorly functioning mitochondrial fragments, determined by the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). The balance between these competing forces is vital for mitochondrial function, and disturbances in this process are observed widely in neurodegenerative conditions (Akbar et al., 2016). Pathological mitochondrial fragmentation is present in commonly used animal models of neonatal HI brain injury (Baburamani et al., 2015; Akbar et al., 2016). As metabolic deficits are found in the areas that will develop damage over time in the neonatal brain after HI, targeting mitochondrial function seems a likely avenue for neuroprotection (Blennow et al., 1995; Blomgren and Hagberg, 2006).

Beyond their role in energy metabolism, mitochondria lie at the crux of life and death within the cell, as several cell death pathways converge and initiate at the organelle. The translocation of factors localized at the mitochondria, such as cytochrome c (cyt c) and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), are precursors to apoptotic cell death. Oxidative stress after HI tips the balance of Bcl-2 family that acts competition to regulate mitochondrial membrane permeability that controls the subsequent release of apoptotic factors (Suen et al., 2008; Thornton et al., 2012). Apoptosis is developmentally upregulated in the neonatal brain, and any shift towards apoptotic signaling leads to exacerbated cell death in comparison to the adult brain. This is driven by several factors that ultimately culminate in a unique sensitivity to ischemic insult. Ca2+ over-influx is a powerful stimulus to both apoptotic and necrotic cell death, and is exacerbated by developmental upregulation of NMDA receptors. Likewise, several apoptotic factors such as caspase-3 and Apaf-1 are far more prevalent in the neonatal brain, as programmed cell death is critical for neural development. This is exacerbated by elevated mitochondrial release of cyt c in the neonate. Cyt c, once translocated to the cytosol, binds to Apaf-1, activating it and forming a structure called the apoptosome. Formation of this complex induces the cleavage of bound procaspase-9 to its active form. Activated caspase-9 activates caspase-3, the final “executioner” caspase, via cleavage and initiates a cascade of proteolytic degradation of cellular components, culminating in characteristic apoptotic cell death (Elmore, 2007). Due to the pivotal place of mitochondria in this process, it follows that mitoprotective strategies may improve the condition of the neonatal brain after HI injury, in part, by ameliorating neuronal cell death.

Currently, the only approved treatment for HIE is therapeutic hypothermia (TH). TH, however, has significant limitations regarding application and efficacy (Nolan et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012; Datta, 2017). TH is a therapeutic strategy practiced in HIE and cardiac arrest, wherein the body temperature of the patient is lowered with specialized equipment to a range of 32–34 °C for a duration of 12–24 hours (Kim et al., 2012; Datta, 2017). Although TH does have protective effects against HI damage, its application is limited by a tight time window within which TH is efficacious. TH must be administered within hours of birth, delivering diminishing returns as the time between HI insult and medical intervention increases. Beyond this, TH, even when deployed successfully, is of limited efficacy, and comes with the potential for adverse cardiovascular effects (Kim et al., 2012). These factors, taken together, necessitate the development of new therapeutic options that can be implemented within a longer timeframe and with greater efficacy to serve the needs of patients and their families.

One emerging therapeutic method targeting the mitochondria lies in photobiomodulation (PBM). Shortly after the development of laser technology it was applied to biological systems, wherein it was first discovered to accelerate hair growth and was soon applied to several biological systems. In recent years, PBM has been applied to multiple brain injury models, facilitated by the penetrance of near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths through biological tissue, including the skull of both rodents and humans. The deep penetrating range of NIR light depends on the gap between the absorption spectra of water and biological chromophores (Chung et al., 2012). PBM has shown protective properties against mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal cell death in animal models of stroke, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Traumatic brain injury (TBI), although these benefits have yet to be successfully translated to the clinic (Zivin et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2012; Oron and Oron, 2016; Xuan et al., 2016; Berman et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017). While the mechanisms underlying PBM are largely unknown, current knowledge posits that it depends on stimulation of mitochondrial function, with cytochrome c oxidase (CCO) being the primary acceptor of light (Chung et al., 2012). Previous studies by our lab in other models have shown that PBM stimulation results in immediate and long-lasting increases in ATP production and mitochondrial function, as well as significant resistance to oxidative stress. As such, we hypothesize that PBM will provide neuroprotection against neonatal HI via promotion of mitochondrial function and preservation of healthy mitochondrial dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design and Neonatal Rat HI model

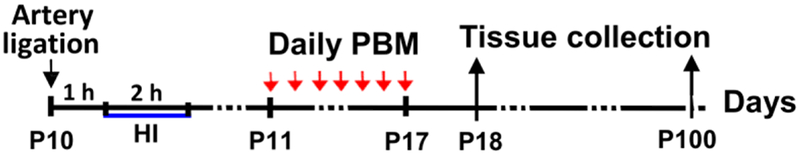

A modified version of the Rice-Vannucci model (Rice et al., 1981) was used in this study. Postnatal (P) 10 pups was assigned to 3 groups (N = 6–12/group): 1) Sham HI, 2) HI + sham PBM, 3) HI + PBM. This model begins with unilateral permanent occlusion of the right common carotid artery. Unsexed P10 pups were separated from their dam and inhaled isoflurane anesthesia was induced and maintained throughout the surgical procedure. Body temperature was maintained throughout surgery and recovery at 37°C via a heating pad and measured via rectal thermometer. An incision was made along the front of the neck, and the right common carotid was exposed. Nerve bundles were gently separated, and the artery was tightly occluded with surgical twine. The wound was closed via surgical glue, subdermal buprenorphine was administered, and the animal was returned to the dam for a 1 h recovery. After this period, pups was placed in a sealed 2 L bag filled with a hypoxic atmosphere (6% O2 balanced with N2) for approximately 2 h, with the body temperature maintained by placing the hypoxia bags in a heated water bath maintained at 37°C. Pups were then removed from the hypoxia bag, labeled, and returned to their dam. All procedures were approved by the local ethical committee and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. All efforts were made to minimize the suffering and the number of pups used in the surgical and experimental procedures. The protocol for induction of HI model, PBM treatment, behavioral test and tissue collection are shown in the experimental design (schematic diagram Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of experimental design. Timepoints of hypoxic ischemia (HI) induction, photobiomodulation (PBM) treatment, and tissue collection are shown.

Photobiomodulation (PMB) Treatment

Transcranial PBM treatment was administered via a continuous wave diode laser with a wavelength of 808 nm (808M100, Dragon Lasers), as described in our previous work (Lu et al., 2017). Laser radiation was focused into a 1 cm2 round spot with an expanding lens and a fiber optic cable and delivered transcranially by centering the beam 3 mm posterior from the eyes and and 2 mm anterior from the ears. All treatment was performed while the animal is briefly restrained in a transparent DecapiCone (DCL-120, Braintree Scientific), including control treatment animals. Laser power was adjusted to yield a cortical power density of 25 mW/cm2. Treatment was maintained for 2 min once daily for 7 days, delivering a daily dosage of 3 J/cm2 at the cerebral cortex tissue level (calculated by total irradiated time (seconds) × power output (mW/cm2)/1000, expressed as J/cm2). After treatment, rats was gently removed the DecapiCone and returned to their home cage. Two laser power meters (#FM33–056, Coherent Inc, USA; and #LP1, Sanwa, Japan) were used to measure the power density passing through the skullcap and scalp placed under a section of DecapiCone. Settings were recorded and used across experiments. Periodically, these measurements were taken again to account for power drift inherent in laser systems.

Histological Evaluation

Histological examination of brain tissue loss and neuronal survival and death was conducted by cresyl violet staining and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), as described previously (Zhang et al., 2009; Ahmed et al., 2016; Ahmed et al., 2017). Briefly, rats were anesthetized and transcardially flush-perfused with ice-cold saline and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The rat brains were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek) and coronal sections (25 μm thick) were obtained on a Leica Cryostat (Leica Microsystems). Brain sections were washed with 0.4% Triton X-100 in PB and stained with cresyl violet (0.01% w/v) for 10 min, followed by graded ethanol dehydration and covering slide. The stained sections were examined, and images were captured using light microscopy. The mean infarct area was calculated according to the following formula: infarct size = (area of contralateral hemisphere – area of ipsilateral hemisphere) / area of contralateral hemisphere × 100 %. To examine relative neuronal density, the numbers of surviving neurons in the area (200 μm × 200 μm square) of the medial CA1 pyramidal layers and somatosensory (S1) cortex were counted from 3–5 representative sections of each animal (>100 μm gap between each section in the coronal plane, ~2.5–4.5 mm posterior from Bregma). Intact, normal-appearing neurons that displaying round soma and distinct stained nuclei, as appear in sham animals, were counted as surviving neurons. Neurons with abnormal-appearing condensed, pyknotic and shrunken nuclei were judged as dead ones. TUNEL labeling was performed on brain sections using a Click-iT® Plus TUNEL assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and the images were captured using a Zeiss LSM700 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). The number TUNEL-positive cells in the examined areas (200 μm × 200 μm) were counted and data were presented as mean ± standard error (SE) (N = 8–12) from independent animals in each group.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Microscopy

Immunofluorescence staining was performed suing standard protocol as previously described (Zhang et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2017). In brief, sections were washed with 0.4% Triton X-100 and blocked in 10% donkey serum followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4˚C. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: anti-Tom20 (Proteintech Group); anti-phospho-Histone H2A.X Ser139 (Cell Signaling); anti-NeuN (Millipore), and anti-4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and anti-Malondialdehyde (MDA) from Abcam Inc. Sections were then washed and incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor donkey anti-mouse/rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h, washed, coverslipped and sealed in VECTASHIELD mounting medium with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories). To determine the level of total mitochondrial fragmentation, the acquired images of Tom20 fluorescent were thresholded, filtered (median, 2.0 pixels) and binarized, using ImageJ software (NIH image program, version 1.49). The counts of total mitochondrial fragmentation were defined by normalization of the number of total mitochondrial particles to total mitochondrial areas, as described in our recent work (Lu et al., 2017). To determine the depolarization level of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), MitoTracker Red CMXRos (100 μl, 50 ng/ml, Life Technologies) was administered via tail vein injection 5 min before tissue collection, as described in our previous work (Lu et al., 2016). All the fluorescence images were captured on LSM700 confocal laser microscope and analyzed using Image J software.

Brain Tissue Homogenates

As described previously (Han et al., 2015), animals were sacrificed under deep anesthesia from sham and HI group at P18. Brain tissue of cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 region were quickly separated and frozen in dry ice. Brain tissues were then homogenized using a Teflon homogenizer in ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH7.40), 150 mM NaCl, 12 mM β-glycerophosphate and inhibitor cocktails of proteases and enzymes (Thermo Scientific). The homogenates were vigorously mixed for 20 min on a rotator and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to yield total protein in the supernatants. Protein concentrations were determined using a Modified Lowry Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce).

Quantification of ATP Production Levels

To investigate the changes of mitochondrial function after PBM treatment, the levels of ATP concentration were determined using an ENLITEN® rLuciferase/Luciferin kit (FF2021, Promega) according to the kit protocol, as described previously (Lu et al., 2016). Briefly, total protein samples (30 μg) were suspended in 100 μL of reconstituted rL/L reagent buffer (pH7.75, containing luciferase, D-luciferin, Tris-acetate buffer, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), magnesium acetate, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and dithiothreitol (DTT)). Light emissions at 10 s intervals were measured in a microplate luminometer (PE Applied Biosystems) and ATP content values were determined from the ATP standard curve. The final levels of ATP concentration were expressed as percentage changes compared to sham control group.

Western Blotting and Quantification of Protein Carbonyl Content

The levels of protein carbonyls in the proteins from cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 at P18 were measured using an OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (EMD Millipore Corporation) following the manufacturer’s protocol, as described in our work (Li et al., 2018). Briefly, protein was denatured and derivatized to 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (DNP) by incubation with 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH). Electrophoresis was performed on 4–20 % SDS-PAGE and proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were then probed with anti-DNP primary antibody, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method under ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare). The membranes were then reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody (Proteintech Group). The level of protein carbonylation, representing oxidative stress status, was normalized to the corresponding loading controls and expressed as percentage changes versus sham control group.

Measurement of Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 Activity

As described previously by our laboratory, caspase-9 and caspase-3 activity was measured by incubation of the proteins fluorometric substrates Ac-DEVD-AMC and Ac-LEHD-AMC, respectively (Lu et al., 2016). Briefly, the reaction was initiated by mixing equal amount of the proteins (30 μg) from cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 with specific substrate in the assay buffer and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The fluorescence of free AMC, corresponding to the proteolytic activity of caspase, was measured on a spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer). Relative caspase activity in each sample was expressed as the changes of fluorescent units and compared between groups.

Data analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SE and analyzed using SigmaStat software (Systat Software). Statistical analyses were carried out using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) post hoc tests to determine group differences. When only two groups were compared, a Student’s t-test was performed to detect significant changes following treatment. Statistical significance was accepted at the 95% probability values (corresponding to P < 0.05).

Results

PBM treatment decreased hemispheric brain shrinkage and neuronal cell death induced by HI insult

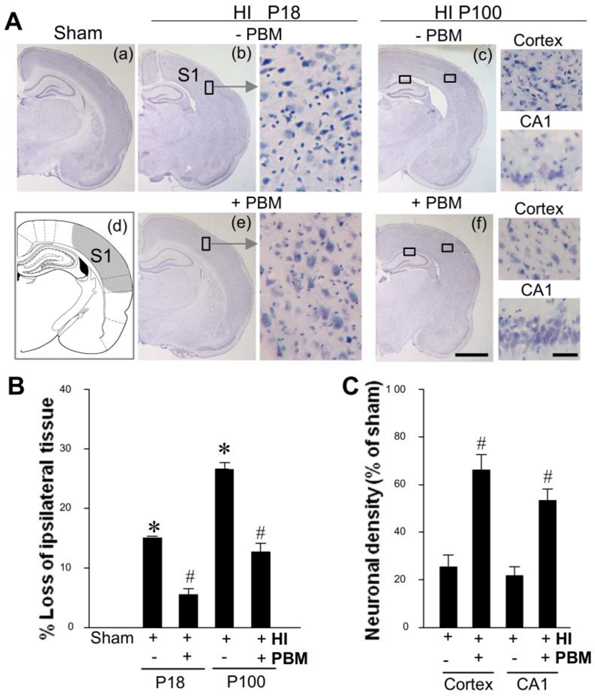

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic (HI) brain injuries invoke pronounced neuronal death, glial activation and lead to secondary maturational disturbances. These neuropathological features are pronounced in specific brain regions, including the sensorimotor cortex and dorsal hippocampal subregions. Insult to these regions can induce subsequent sensory and motor dysfunction, as well as learning and attentional deficits (van de Looij et al., 2014). In current study, the neuronal morphology of sensorimotor cortex and hippocampal CA1 region was examined on both early timepoint (P18) and late timepoint (P100) after HI via Nissl staining. As shown in Fig. 2A, neonatal rats subjected to HI insult displayed dramatic neuronal death in the cortex and hippocampal CA1 regions on both P18 and P100, which was strongly attenuated by PBM treatment. Further quantitative analysis revealed that the loss of ipsilateral brain tissue in HI rats was approximate 17% on P18 and 32% on P100 after HI injury. PBM, however reduced brain loss at the aforementioned timepoints to 5% and 12%, respectively (Fig. 2B). This robust preservation of brain volume is indicative of both short-term and long-term protective effects. Further analysis for relative neuronal density suggested that PBM treatment also dramatically rescued the decreased neuronal density in both the cortex and hippocampal CA1 regions of HI rats, as shown in Fig. 2C.

Fig. 2.

PBM treatment reduced hemispheric brain tissue loss and neuronal death. A Brain tissues were examined on both P18 and P100 after HI. Location of somatosensory (S1) cortex is shown in (d). B, C Brain damage was evaluated by calculation of the loss of ipsilateral tissue (at p18 and p100) and relative neuronal density (at p100) in the cortical infarct area and damaged hippocampal CA1 region (N = 8–12). Scale bar: 500 μm (in the overview) and 50 μm (in the enlarged area). *P < 0.05 versus sham, #P < 0.05 versus HI control group without PBM treatment.

PBM treatment suppressed HI-induced mitochondrial fragmentation

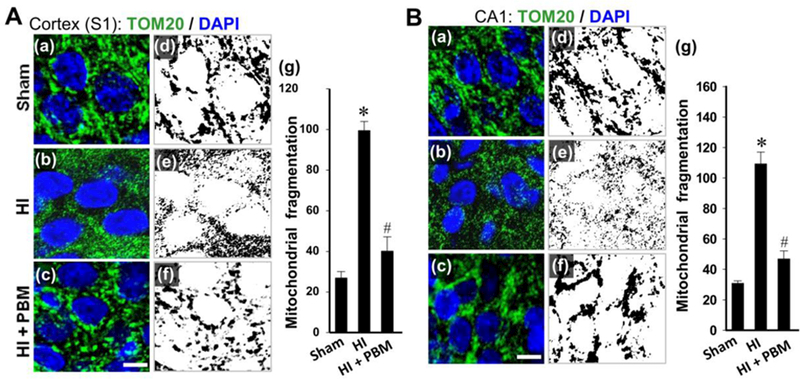

Ischemic neuronal death has been demonstrated to involve the imbalance of mitochondrial dynamics, characterized by mitochondrial fragmentation. As a critical organelle that maintains neuronal survival, mitochondrial dysfunction will initiate mitochondria-dependent apoptotic signaling pathway, and accelerate downstream cell death cascade. Therefore, mitochondria-targeted strategies might be effective on the attenuation of HI injury. To examine mitochondrial morphology in cortex and hippocampal CA1 regions from P18 rats, immunofluorescence imaging of Tom-20 was carried out, and the segments were further separated, thresholded, filtered and binarized using Image J software. Mitochondria in both the cortex (Fig. 3A) and hippocampal CA1 (Fig. 3B) regions of HI rats displayed a significantly higher degree of fragmentation than sham control. In contrast, PBM treatment profoundly relieved the mitochondrial fragmentation to a degree that is comparable to that observed in sham animals. This result indicates a crucial ability of PBM intervention on mitochondrial integrity by maintaining a healthy balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion processes, which may indicate a potent mechanism for neuronal survival in the context of HI brain injury.

Fig. 3. Effect of PBM treatment on HI-induced changes in mitochondrial fragmentation of cortex and hippocampal pyramidal neurons.

A, B (a-c): Representative immunofluorescence images of Tom20 staining (green) counterstained with nuclear marker DAPI (blue) of cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 neurons from P18 animals. Scale bar: 5 µm. A, B (d-g): The immunofluorescence of Tom20 was separated, threshold d, filtered and binarized using Image J program. The counts of total mitochondrial fragmentation were calculated by normalization of the number of total mitochondrial segments to total mitochondrial areas. Data are presented as means ± SE (N = 4–6 in each group). *P < 0.05 versus sham HI control, #P < 0.05 versus HI or HI + sham PBM group.

PBM treatment attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction induced by HI

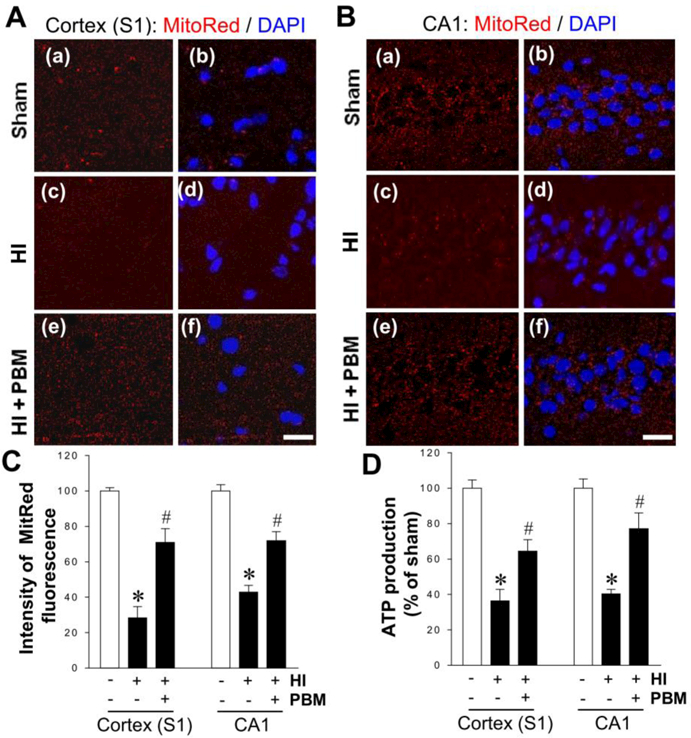

Mitochondrial dysfunction and energy failure play a pivotal role in the development and progression of ischemic brain injury and neuronal death. As a critical organelle that maintains neuronal survival, mitochondrial dysfunction can initiate mitochondria-dependent apoptotic signaling pathway, accelerating downstream cell death cascades. Therefore, mitochondria-targeted strategies may prove effective in attenuating short-term and long-term HI injury. To investigate mitochondrial dysfunction, functionally critical mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was examined in P18 animals, with MitoTracker Red fluorescent dye, a marker of MMP. Confocal images of MitoRed staining in Fig. 4A&B and further quantitative analysis in Fig. 4C revealed drastic decreases in MitoTracker Red signal of both cortex and hippocampal CA1 neurons from HI rats compared with Sham control. PBM treatment, in contrast strongly reversed the trend of decreased fluorescent signal in HI rats, suggesting significant attenuation of mitochondrial MMP collapse. Next, ATP production was measured in total protein fraction samples from both the cortex and the hippocampal CA1 subregion. As shown in Fig. 4D, rats subjected to HI insult displayed remarkable ATP decline in both regions, which was potently reversed by PBM treatment. Taken together, these results demonstrated a robust ameliorating effect of PBM intervention on HI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in neonatal rats.

Fig. 4. Effect of PBM treatment on HI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in the infarct brain.

A, B Representative microscopy images of MitoTracker Red immunofluorescence in cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 neurons from P18 animals. The tissue sections were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars = 20 μm. C The intensity level of MitoTracker fluorescence associated with MMP was determined and expressed as percentage changes compared with the sham group. D The level of ATP production was detected in the indicated protein samples from each group at P18 and the value was compared within groups. *P < 0.05 versus sham, #P < 0.05 versus HI control group without PBM treatment. Data are means ± SE from 4–6 animals in each group.

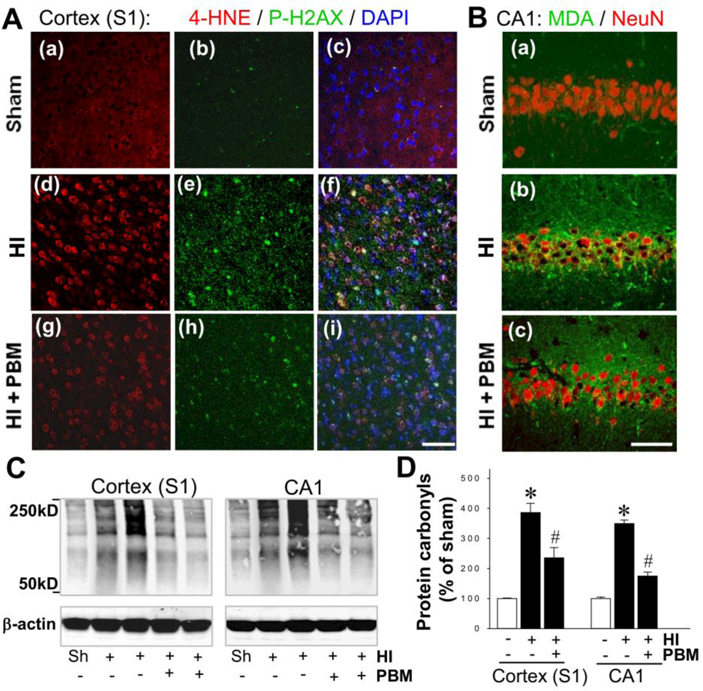

PBM treatment abated oxidative damage in the HI infarct brain

Evidence has accumulated, from our studies and others, which suggests that neonatal hypoxia-ischemia injury induces long-lasting oxidative stress, a process exacerbated by mitochondrial dysfunction (Odorcyk et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). The positive effect of PBM treatment on mitochondrial function demonstrated above leads us to hypothesize that HI-triggered oxidative damage to cellular components in neonatal rats may be attenuated by PBM intervention. First, oxidative damage in the S1 cortex was investigated by measuring the markers of lipid peroxidation (4 HNE) and DNA double-strand breaks (P-H2A.X), as shown in Fig. 5A. In agreement with the inhibitory effect on mitochondrial dysfunction, PBM was shown to markedly reduce the HI-induced surge of both 4-HNE and P-H2A.X expression. Similar results were found in the hippocampal CA1 subregion after staining for MDA, another widely used marker of lipid peroxidation (Fig. 5B). Finally, we measured levels of protein carbonyls generated from oxidative damage to cellular proteins via western blot analysis (Fig. 5C). Quantitative analysis indicated that protein carbonyl production in both the cortex and hippocampal CA1 infarct regions was profoundly suppressed by PBM treatment, further indicating the ability of PBM to decrease HI-induced oxidative damage.

Fig. 5. Effect of PBM treatment on HI-induced oxidative damage in the infarct brain.

A, B Representative microscopy images of the damaged brain regions showing the staining of 4-HNE, P-H2AX (S139), DAPI, malondialdehyde (MDA) and NeuN at P18 from each group. Scale bars = 50 μm. C,D The level of protein carbonyls, representing oxidative stress, was measured at P18 using a protein carbonyl content assay kit and Western blotting. Data are means ± SE (N = 4–6) expressed as percentage changes versus sham control group. *P < 0.05 versus sham, #P < 0.05 versus HI control group.

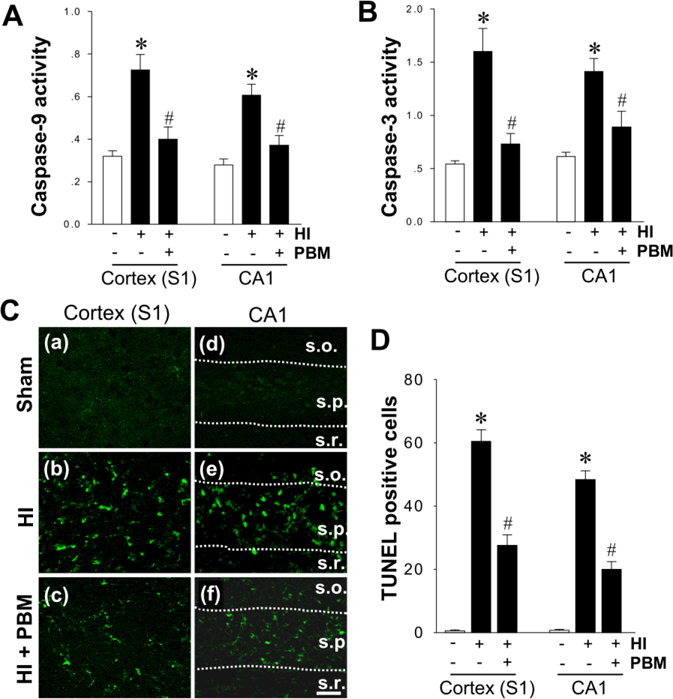

PBM treatment suppressed activation of caspase-9/caspase-3 apoptotic pathway in HI rats

It is well established that HI insult leads to activation of mitochondria-dependent caspase-9/caspase-3 apoptotic pathway in neonatal rats. Therefore, we next measured the anti-apoptotic effect of PBM treatment in HI infarct brains. As shown in Fig. 6A&B, fluorometric substrate assays for samples taken from the cortex and hippocampal CA1 region at P18 revealed that HI induced a remarkable increase in the activity of pro-apoptotic proteins caspase 9 and 3. This effect was sharply blunted by PBM treatment. Finally, apoptosis in both infarct regions was examined using TUNEL staining. As shown in Fig. 6C&D, HI rats consistently displayed robust increases in TUNEL–positive cells compared with sham control animals, which was dramatically attenuated by PBM treatment.

Fig. 6. Effect of PBM treatment on caspase-9 and caspase-3 activity and apoptotic cell death induced by HI.

A, B The change of caspase-9 and caspase-3 activity in the proteins from cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 was examined using specific AMC-based fluorometric substrates at P18 from sham and HI rats. The fluorescence of free AMC was measured and compared between groups. C Representative confocal microscopy images depict fluorescent TUNEL staining (green) in cortex (S1) and hippocampus CA1 region (s.o., stratum oriens; s.p., stratum pyramidal and s.r., stratum radiatum). Scale bar: 20 µm. D The numbers of TUNEL positive cells from the indicated groups were counted and statistically determined. Results are means ± SE from 4–5 animals in (A) and (B), and 8–12 animals in (C) and (D) in each group. *P < 0.05 versus sham, #P < 0.05 versus HI control group.

Discussion

Perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is one of the leading contributors to mortality in neonates, leading to long-term neurological disability and pathologies, such as spasticity, cognitive impairment, sensory deficits and motor abnormality (Vannucci et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2017). Despite years of investigation, treatment for HIE remains extremely limited. In the current study, we demonstrated for the first time that PBM treatment exerts a beneficial effect on a wide breadth of HIE pathological analogues in the neonatal HI rat model. PBM had pronounced effects on cerebral infarct size and neuronal cell death in the cortex and hippocampal CA1. In line with the proposed mechanisms of PBM, post-treatment with PBM suppressed HI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and fragmentation and consequent oxidative neuronal damage. These results provide insight into protective mechanisms of a novel treatment paradigm for neonatal HI injury that could offer recovery for those affected by HIE.

HI injury has been demonstrated to exact particular damage to the cerebral cortex and dorsal hippocampus, which accounts for the high frequency of locomotor and cognitive deficits in neonates suffering from HIE (McQuillen et al., 2003; Albrecht et al., 2005). Clinical studies on human preterm infants with electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed reduced background activity, which can be used as sensitive marker of damaged cortical circuits (Toet et al., 1999). Reduced dendritic spine maturation and synapse formation of cortical neurons is a further indicator of future sensorimotor deficits. As well, learning and memory impairment is a common clinical characteristic that follows for a lifetime those who survive the initial HI insult. The dorsal hippocampus, the CA1 region in particular, is frequently studied due to its critical role in learning and memory (Goodrich-Hunsaker et al., 2008). Accordingly, our study demonstrated that HI injury in neonatal rats caused profound ipsilateral brain lesions in both the cortex and hippocampal CA1 regions, observed at both P18 and P100. PBM treatment has been well documented to impart a protective effect on neurodegenerative diseases by our lab and others in conditions as AD, stroke and aging (Lu et al., 2017; Salehpour et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). The current work corroborates this by demonstrating that PBM intervention at the early stage of neonatal HI injury exhibits pronounced effects on the preservation of brain lesion volume, both over the short-term and long-term time windows.

As the primary source of energy for the brain and a central hub for cell death signaling, mitochondria play a critical role for cell survival. Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by ischemic insult causes primary energetic failure and initiates a battery of self-perpetuating pathological events that ultimately lead to neuronal degeneration and apoptosis, in part mediated by excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (Akbar et al., 2016; Ham and Raju, 2017). This process causes long-term damage that prolongs the impact of the initial insult, causing deficits in energy production and disruption of mitochondrial dynamics, as preservation of mitochondrial integrity is associated with structural dynamics by balancing fission and fusion processes (Bertholet et al., 2016). The dynamic balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion can determine their morphology and enable quick adaptation for energetic needs, as well as maintaining mitochondrial integrity. These processes are controlled by a series of factors, primarily GTPases, i.e. DRP1, FIS1, OPA1 and MFN1, which are located on mitochondrial outer membrane and mediate the processes of mitochondrial fission and fusion, respectively. Disturbances in the expression, integrity, and function of these proteins are present in several neurodegenerative disorders. Mitochondrial fragmentation, in particular, is a characteristic hallmark in the pathogenesis of many of these diseases, and is, in part, triggered by the overproduction of fission related proteins (Otera et al., 2013; Chao de la Barca et al., 2016). Following these detrimental morphological alterations, mitochondria undergo exacerbated functional compromise, characterized by declining mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP synthesis deficits. In the current study, we observed that unilateral HI insult to neonatal rats induced significant mitochondrial abnormalities, including extensive mitochondrial fragmentation and subsequent decline in energy production. PBM treatment, however, managed to facilitate ATP production and reverse the trend of mitochondrial fragmentation, a beneficial effect which has been consistently demonstrated in our previous studies involving different neurodegenerative models (Lu et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2017).

Evidence has shown that oxidative stress is a critical mechanism for the development of HI brain injury, and it is strongly linked with alterations and dysfunction of mitochondrial respiratory complex I and IV activity (Wyatt, 1994; Niatsetskaya et al., 2012; Sosunov et al., 2015). Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to a buildup of radical oxidative species via electron leakage, which can feedback and exacerbate mitochondrial impairment through damage to critical mitochondrial components. This damage spills out from the mitochondria into other cellular compartments, causing irreversible damage to critical cellular macromolecules (Akbar et al., 2016; Ham and Raju, 2017). Brain tissue, because of its high level of lipid content, is thus particularly vulnerable to the ravages of oxidative damage (Wang et al., 2014). In this work, we demonstrated that PBM was able to exert robust anti-oxidative effects in the cortex and hippocampal CA1 regions, in line with our results regarding mitochondrial function. This was expressed by a sharp decrease in markers of lipid, DNA, and protein oxidative damage. By protecting against this damage and the subsequent signaling cascade, we believe that PBM mitigates the excessive cell death that follows HI insult and contributes to HIE pathology.

Following mitochondrial damage and resultant oxidative stress, mitochondrial dependent apoptotic pathways are activated. This is initiated by cyt c release, followed by formation of the apoptosome and activation, via proteolytic cleavage, of caspase-3 and caspase-9, triggering an irreversible cascade leading to cell death (Lu et al., 2015). This process is particularly dramatic in the neonatal brain due to developmentally appropriate upregulation of apoptotic factors and their release, as well as a general sensitivity to oxidative stress (Thornton et al., 2012). This death is pronounced in critically sensitive neuronal progenitor pools and oligodendrocyte progenitors, contributing heavily to the developmental deficits and morphological abnormalities underlying HI injury in the neonatal brain (Vannucci and Hagberg, 2004). TUNEL staining revealed dramatic increases in the levels of neuronal apoptosis in the cortex and hippocampal CA1, as observed at P18. PBM attenuated this apoptosis, ameliorating the HI-induced damage. In line with these results, fluorometric substrate assays uncovered a striking upregulation in the activity of pro-apoptotic proteins caspase-3 and caspase-9 in HI infarct brains. This surge in apoptotic signaling was countered by PBM treatment, potentially accounting for the decrease in neuronal apoptotic cell death.

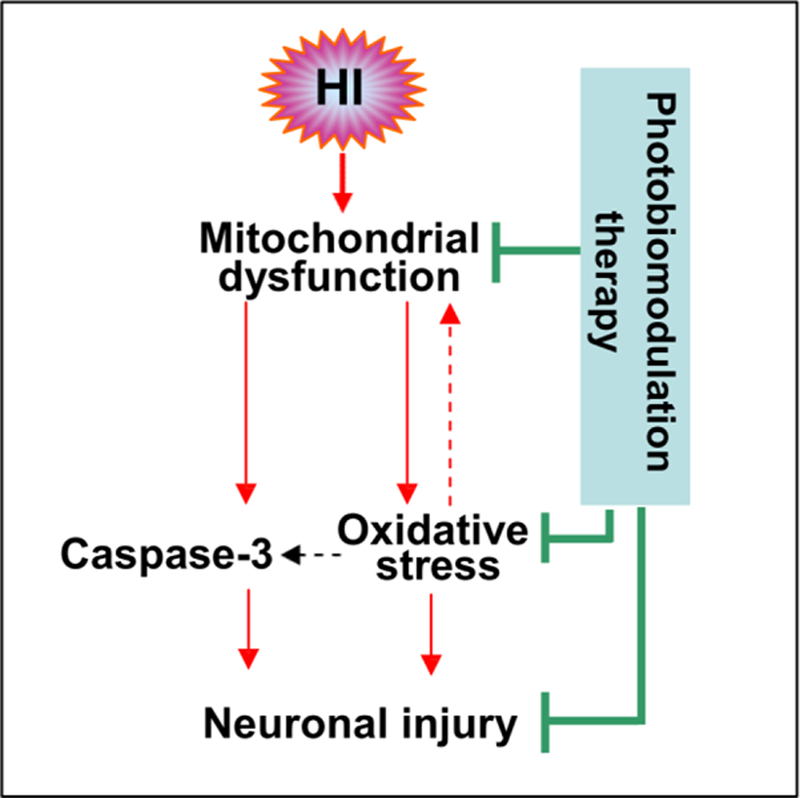

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates the profound neuroprotective effects of PBM treatment on HI injury in neonatal rats. We believe that these effects are a result of, in part, preservation of mitochondrial function and suppression of HI-induced oxidative stress. The result of this is a marked suppression of apoptotic signaling and neuronal cell death, which translates into protection against long lasting hemispheric shrinkage that is characteristic of brain injury in the hypersensitive perinatal period (Fig. 7). Taken together, our findings provide evidence of the efficacy of PBM as a novel non-pharmacological therapeutic option in the management of HI injury that can supplement the limited treatment options that are currently available. We believe that PBM, if successfully translated to the clinic, may help those affected by HIE reach their full potential and spare patients and their families the undue suffering HIE inflicts.

Fig. 7. Schematic summary of the neuroprotective effect of photobiomodulation therapy.

HI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to oxidative stress and caspase-3 activation, resulting in neuronal cell death (apoptosis) in the cortex (S1) and hippocampal CA1 region. Oxidative stress can further attack mitochondria in a positive-feedback manner. Photobiomodulation therapy was able to attenuate these detrimental effects and improve neuronal survival.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: This study was supported by Research Grant NS086929 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed ME, Dong Y, Lu Y, Tucker D, Wang R, Zhang Q (2017) Beneficial Effects of a CaMKIIalpha Inhibitor TatCN21 Peptide in Global Cerebral Ischemia. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN 61:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed ME, Tucker D, Dong Y, Lu Y, Zhao N, Wang R, Zhang Q (2016) Methylene Blue promotes cortical neurogenesis and ameliorates behavioral deficit after photothrombotic stroke in rats. Neuroscience 336:39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar M, Essa MM, Daradkeh G, Abdelmegeed MA, Choi Y, Mahmood L, Song BJ (2016) Mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in neurodegenerative diseases through nitroxidative stress. Brain research 1637:34–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht J, Hanganu IL, Heck N, Luhmann HJ (2005) Oxygen and glucose deprivation induces major dysfunction in the somatosensory cortex of the newborn rat. The European journal of neuroscience 22:2295–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baburamani AA, Hurling C, Stolp H, Sobotka K, Gressens P, Hagberg H, Thornton C (2015) Mitochondrial Optic Atrophy (OPA) 1 Processing Is Altered in Response to Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. International journal of molecular sciences 16:22509–22526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman MH, Halper JP, Nichols TW, Jarrett H, Lundy A, Huang JH (2017) Photobiomodulation with Near Infrared Light Helmet in a Pilot, Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial in Dementia Patients Testing Memory and Cognition. Journal of neurology and neuroscience 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet AM, Delerue T, Millet AM, Moulis MF, David C, Daloyau M, Arnaune-Pelloquin L, Davezac N, Mils V, Miquel MC, Rojo M, Belenguer P (2016) Mitochondrial fusion/fission dynamics in neurodegeneration and neuronal plasticity. Neurobiology of disease 90:3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow M, Ingvar M, Lagercrantz H, Stone-Elander S, Eriksson L, Forssberg H, Ericson K, Flodmark O (1995) Early [18F]FDG positron emission tomography in infants with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy shows hypermetabolism during the postasphyctic period. Acta paediatrica 84:1289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren K, Hagberg H (2006) Free radicals, mitochondria, and hypoxia ischemia in the developing brain. Free radical biology & medicine 40:388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao de la Barca JM, Prunier-Mirebeau D, Amati-Bonneau P, Ferre M, Sarzi E, Bris C, Leruez S, Chevrollier A, Desquiret-Dumas V, Gueguen N, Verny C, Hamel C, Milea D, Procaccio V, Bonneau D, Lenaers G, Reynier P (2016) OPA1-related disorders: Diversity of clinical expression, modes of inheritance and pathophysiology. Neurobiology of disease 90:20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Dai T, Sharma SK, Huang YY, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR (2012) The nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapy. Annals of biomedical engineering 40:516–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colver A, Fairhurst C, Pharoah PO (2014) Cerebral palsy. Lancet 383:1240–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta V (2017) Therapeutic Hypothermia for Birth Asphyxia in Neonates. Indian journal of pediatrics 84:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S (2007) Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicologic pathology 35:495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP (2008) The interactions and dissociations of the dorsal hippocampus subregions: how the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 process spatial information. Behavioral neuroscience 122:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham PB 3rd, Raju R (2017) Mitochondrial function in hypoxic ischemic injury and influence of aging. Progress in neurobiology 157:92–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, Scott EL, Dong Y, Raz L, Wang R, Zhang Q (2015) Attenuation of mitochondrial and nuclear p38alpha signaling: a novel mechanism of estrogen neuroprotection in cerebral ischemia. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 400:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul SE, Ferriero DM (2014) Pharmacologic neuroprotective strategies in neonatal brain injury. Clinics in perinatology 41:119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HN, Pak ME, Shin MJ, Kim SY, Shin YB, Yun YJ, Shin HK, Choi BT (2017) Comparative analysis of the beneficial effects of treadmill training and electroacupuncture in a rat model of neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. International journal of molecular medicine 39:1393–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Yim HW, Jeong SH, Klem ML, Callaway CW (2012) Does therapeutic hypothermia benefit adult cardiac arrest patients presenting with non-shockable initial rhythms?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies. Resuscitation 83:188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HI, Lee SW, Kim NG, Park KJ, Choi BT, Shin YI, Shin HK (2017) Low level light emitting diode therapy promotes long-term functional recovery after experimental stroke in mice. Journal of biophotonics 10:1761–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Yang R, Li P, Lu H, Hao J, Tucker D, Zhang Q (2018) Combination Treatment with Methylene Blue and Hypothermia in Global Cerebral Ischemia. Molecular neurobiology 55:2042–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Tucker D, Dong Y, Zhao N, Zhang Q (2016) Neuroprotective and Functional Improvement Effects of Methylene Blue in Global Cerebral Ischemia. Molecular neurobiology 53:5344–5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Tucker D, Dong Y, Zhao N, Zhuo X, Zhang Q (2015) Role of Mitochondria in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Journal of neuroscience and rehabilitation 2:1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Wang R, Dong Y, Tucker D, Zhao N, Ahmed ME, Zhu L, Liu TC, Cohen RM, Zhang Q (2017) Low-level laser therapy for beta amyloid toxicity in rat hippocampus. Neurobiology of aging 49:165–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillen PS, Sheldon RA, Shatz CJ, Ferriero DM (2003) Selective vulnerability of subplate neurons after early neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 23:3308–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niatsetskaya ZV, Sosunov SA, Matsiukevich D, Utkina-Sosunova IV, Ratner VI, Starkov AA, Ten VS (2012) The oxygen free radicals originating from mitochondrial complex I contribute to oxidative brain injury following hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 32:3235–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan JP et al. (2008) Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A Scientific Statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Stroke. Resuscitation 79:350–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorcyk FK, Kolling J, Sanches EF, Wyse ATS, Netto CA (2017) Experimental neonatal hypoxia ischemia causes long lasting changes of oxidative stress parameters in the hippocampus and the spleen. Journal of perinatal medicine [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oron A, Oron U (2016) Low-Level Laser Therapy to the Bone Marrow Ameliorates Neurodegenerative Disease Progression in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Minireview. Photomedicine and laser surgery 34:627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otera H, Ishihara N, Mihara K (2013) New insights into the function and regulation of mitochondrial fission. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1833:1256–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JE, 3rd, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB (1981) The influence of immaturity on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the rat. Annals of neurology 9:131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumajogee P, Bregman T, Miller SP, Yager JY, Fehlings MG (2016) Rodent Hypoxia-Ischemia Models for Cerebral Palsy Research: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in neurology 7:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehpour F, Ahmadian N, Rasta SH, Farhoudi M, Karimi P, Sadigh-Eteghad S (2017) Transcranial low-level laser therapy improves brain mitochondrial function and cognitive impairment in D-galactose-induced aging mice. Neurobiology of aging 58:140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Blomgren K, Gimlin K, Ferriero DM, Noble-Haeusslein LJ (2013) Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Progress in neurobiology 106–107:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Wells L, Dodd K (2000) The continuing fall in incidence of hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy in term infants. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 107:461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosunov SA, Ameer X, Niatsetskaya ZV, Utkina-Sosunova I, Ratner VI, Ten VS (2015) Isoflurane anesthesia initiated at the onset of reperfusion attenuates oxidative and hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. PloS one 10:e0120456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen DF, Norris KL, Youle RJ (2008) Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes & development 22:1577–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton C, Rousset CI, Kichev A, Miyakuni Y, Vontell R, Baburamani AA, Fleiss B, Gressens P, Hagberg H (2012) Molecular mechanisms of neonatal brain injury. Neurology research international 2012:506320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Toet MC, Hellstrom-Westas L, Groenendaal F, Eken P, de Vries LS (1999) Amplitude integrated EEG 3 and 6 hours after birth in full term neonates with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition 81:F19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Looij Y, Chatagner A, Quairiaux C, Gruetter R, Huppi PS, Sizonenko SV (2014) Multi-modal assessment of long-term erythropoietin treatment after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury in rat brain. PloS one 9:e95643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci RC, Connor JR, Mauger DT, Palmer C, Smith MB, Towfighi J, Vannucci SJ (1999) Rat model of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Journal of neuroscience research 55:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci SJ, Hagberg H (2004) Hypoxia-ischemia in the immature brain. The Journal of experimental biology 207:3149–3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang W, Li L, Perry G, Lee HG, Zhu X (2014) Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1842:1240–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt JS (1994) Noninvasive assessment of cerebral oxidative metabolism in the human newborn. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London 28:126–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Guo X, Yang Y, Tucker D, Lu Y, Xin N, Zhang G, Yang L, Li J, Du X, Zhang Q, Xu X (2017) Low-Level Laser Irradiation Improves Depression-Like Behaviors in Mice. Molecular neurobiology 54:4551–4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan W, Huang L, Hamblin MR (2016) Repeated transcranial low-level laser therapy for traumatic brain injury in mice: biphasic dose response and long-term treatment outcome. Journal of biophotonics 9:1263–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Tucker D, Dong Y, Wu C, Lu Y, Li Y, Zhang J, Liu TC, Zhang Q (2018) Photobiomodulation therapy promotes neurogenesis by improving post-stroke local microenvironment and stimulating neuroprogenitor cells. Experimental neurology 299:86–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Tucker LD, DongYan, Lu Y, Yang L, Wu C, Li Y, Zhang Q (2018) Tert-butylhydroquinone post-treatment attenuates neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in rats. Neurochemistry international 116:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QG, Raz L, Wang R, Han D, De Sevilla L, Yang F, Vadlamudi RK, Brann DW (2009) Estrogen attenuates ischemic oxidative damage via an estrogen receptor alpha-mediated inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 29:13823–13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QG, Wang RM, Scott E, Han D, Dong Y, Tu JY, Yang F, Reddy Sareddy G, Vadlamudi RK, Brann DW (2013) Hypersensitivity of the hippocampal CA3 region to stress-induced neurodegeneration and amyloidogenesis in a rat model of surgical menopause. Brain : a journal of neurology 136:1432–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivin JA et al. (2009) Effectiveness and safety of transcranial laser therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 40:1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]