Abstract

Skin lipids (e.g. fatty acids) are essential for normal skin functions. Epidermal fatty acid-binding protein (E-FABP) is the predominant FABP expressed in skin epidermis. However, the role of E-FABP in skin homeostasis and pathology remains largely unknown. Herein, we utilized the 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) and 12-O-tetradecanolyphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced skin tumorigenesis model to assess the role of E-FABP in chemical-induced skin tumorigenesis. Compared to their wild type (WT) littermates, mice deficient in E-FABP, but not adipose FABP (A-FABP), developed more skin tumors with higher incidence. TPA functioning as a tumor promoter induced E-FABP expression and initiated extensive flaring inflammation in skin. Interestingly, TPA-induced production of IFNβ and IFNλ in the skin tissue was dependent on E-FABP expression. Further protein and gene expression arrays demonstrated that E-FABP was critical in enhancing IFN-induced p53 responses and in suppressing SOX2 expression in keratinocytes. Thus, E-FABP expression in skin suppresses chemical-induced skin tumorigenesis through regulation of IFN/p53/SOX2 pathway. Collectively, our data suggest an unknown function of E-FABP in prevention of skin tumor development and offer E-FABP as a therapeutic target for improving skin innate immunity in chemical-induced skin tumor prevention.

Keywords: E-FABP, Keratinocyte, Skin tumorigenesis, p53, SOX2

INTRODUCTION

As the largest organ in mammals, skin consists of epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue and serves as a physical and immunologic barrier to the external environment (Pasparakis et al., 2014; Proksch et al., 2008). Keratinocytes are the primary cell type in the epidermis undergoing continuous cycles of homeostatic proliferation and differentiation to maintain skin integrity and to protect against various environmental insults. Skin squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common skin cancer. Most of the increasing incidence is due to UV-induced SCC, especially in light-skinned individuals with chronic cutaneous inflammation (Leiter et al., 2014; Lund et al., 2016). Despite recent studies revealing different cellular and molecular mechanisms, such as upregulation of SOX2 in cancer stem cells, in the control of initiation and progression of primary skin SCC(Boumahdi et al., 2014; Lapouge et al., 2012), how normal keratinocytes maintain their homeostasis and keep their functionality to prevent tumorigenesis during the process of continuous skin differentiation remains unknown.

Epidermal fatty acid binding protein (E-FABP, also known as mal1 or FABP5) was first cloned from psoriatic skin tissue due to its high upregulation in psoriatic keratinocytes (Madsen et al., 1992). It belongs to the family of FABPs because it binds long-chain FAs and other hydrophobic ligands in the cytosol. Although FABPs are believed to play important roles in metabolic and inflammatory pathways through coordinating lipid transport and metabolism inside cells (Hotamisligil and Bernlohr, 2015; Storch and McDermott, 2009), the exact role of E-FABP in keratinocytes remains largely unknown. Several recent studies report that E-FABP expression in keratinocytes contributes to the water permeability barrier of the skin and promotes keratinocyte differentiation by enhancing fatty acid mediated-keratin 1 expression (Owada et al., 2002; Ogawa et al., 2011). Our group, and others, have demonstrated that E-FABP is also expressed in immune cells and plays a role in regulating T cell differentiation and macrophage pro-inflammatory functions (Li et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2015). Given the emerging role of E-FABP in both keratinocytes and immune cells, we reasoned that E-FABP expression in the skin tissue might represent a previously unknown molecular mechanism in maintaining normal skin homeostasis and surveillance, thus playing a critical role in the prevention of environmentally-induced tumorigenesis in skin.

DMBA(7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene)/TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate, also known as PMA in cellular studies) model is commonly used to chemically induce multistage skin tumorigenesis due to its easy performance (Abel et al., 2009; Kemp, 2005). The use of this two-step tumorigenesis model has identified many host-derived factors associated with skin tumor development. For example, p53 expression in stratified epithelia protects against DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumor growth and malignancy (Page et al., 2016). Constitutive expression of type I interferons (IFNs) is critical in skin tumor prevention (Chen et al., 2009). Herein, we utilized the DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumorigenesis mouse model to determine whether and how host expression of E-FABP played a critical role in skin tumor development. We provide evidence to show that E-FABP expression in keratinocytes prevents skin tumor development by enhancing p53-mediated SOX2 downregulation in keratinocytes.

RESULTS

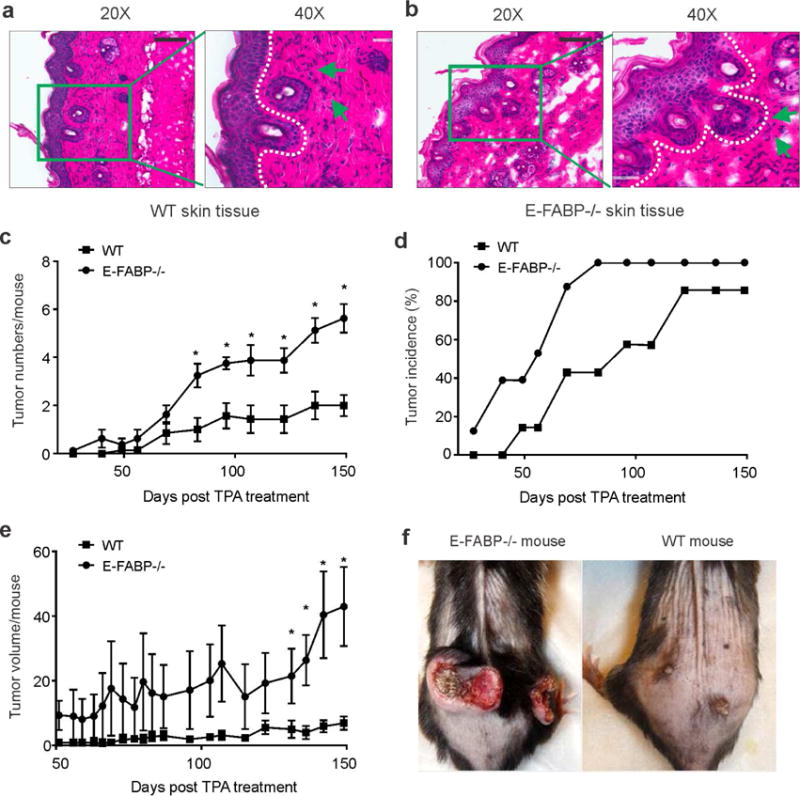

Loss of E-FABP promotes DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumorigenesis

To determine the role of E-FABP in skin tumor development, WT and E-FABP−/− littermates were subjected to the DMBA/TPA protocol to chemically induce skin tumorigenesis. We did not observe any noticeable differences of the skin appearance after DMBA application between WT and E-FABP−/− mice. However, E-FABP−/− mice appeared to be more sensitive than WT mice in response to the TPA treatment with development of red skin in some TPA-treated areas, suggesting an early difference of TPA-induced inflammatory responses between WT and E-FABP−/− mice. Histological analysis showed an obvious keratinocyte proliferation with comparable infiltration of inflammatory cells in both WT and E-FABP−/− mice. Interestingly, keratinocytes in E-FABP−/− mice exhibited atypical dysplasia throughout the epidermis as compared to WT mice (Figure 1A, 1B). About 10 days after TPA treatment was initiated, E-FABP−/− mice began to develop small skin papillomas while it took about 6 weeks before similar tumors were observed in WT mice (Figure 1C). With additional TPA applications, skin tumor numbers/mouse and incidence were significantly higher in E-FABP−/− mice than in WT mice (Figure 1C, 1D). Moreover, tumor burden as calculated by tumor volume/size in E-FABP−/− mice was greater than in WT mice (Figure 1E, 1F). As skin tissue also expresses adipose FABP (A-FABP), another FABP family member (Zhang et al., 2015), we also compared skin tumor development in WT and A-FABP−/− mice using the same DMBA/TPA protocol. There was no obvious impact of the DMBA/TPA regime in A-FABP−/− mice on skin tumor initiation and development as compared to their WT littermates (supplementary Figure S1A, S1B). These results indicate that expression of E-FABP, but not A-FABP, in mouse skin tissue is essential in suppressing chemical-induced skin tumorigenesis.

Figure 1. Expression of E-FABP suppresses DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumor development.

(a,b) Histological analysis (H&E staining) of keratinocyte proliferation and inflammatory cell infiltration in WT (a) and E-FABP−/− mice (b) treated with TPA for 7 days (infiltrated inflammatory cells pointed by green arrows) (scale bar = 100μM). c, Average skin tumor numbers per mouse in DMBA/TPA-treated WT and E-FABP−/− mice (n=12/group). d, The incidence of skin tumor formation in WT and E-FABP−/− mice treated with DMBA/TPA. e, Average tumor volume per mouse (mm3) in DMBA/TPA-treated WT and E-FABP−/− mice. f, Representative images of DMBA/TPA-induced tumors in WT and E-FABP−/− mice.

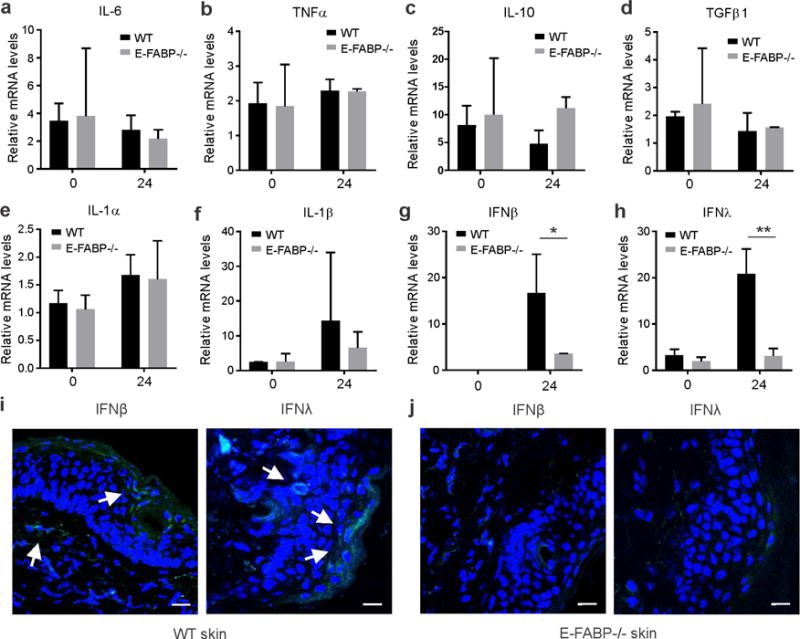

TPA treatment induces E-FABP-independent and dependent inflammatory responses in skin

Given the observed differences in skin responses to TPA treatment between WT and E-FABP−/−mice during tumor development, we first analyzed TPA-induced skin inflammatory responses in these mice. TPA treatment of WT and E-FABP−/− mice for 5h induced an early response of tumor-associated cytokine expression in skin tissues, such as IL-6, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα, IL-10 and TGFβ1, but E-FABP deficiency had no impact on the production of these cytokines (supplementary Figure S2A–S2F). After 24h of TPA treatment, these acute inflammatory responses, including most cytokines and chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL11), dissipated rapidly without significant differences between WT and E-FABP−/− mice (Figure 2A–2F, supplementary Figure S2G–S2J). However, we noticed that type I IFNβ and type III IFNλ, but not type II IFNγ, were significantly upregulated in the skin of WT mice as compared to E-FABP−/− mice (Figure 2G,2H, supplementary Figure S2J). Consistently, elevated levels of IFNβ and IFNλ in the skin of WT mice were confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure 2I, 2J). These results suggest that TPA induces both E-FABP-independent and dependent inflammatory responses during the promotion of tumor development and the diminished expression of IFNβ and IFNλ may contribute to the exacerbated tumor development in E-FABP−/− mice.

Figure 2. TPA treatment induces E-FABP- independent and dependent skin inflammation.

Dorsal skin of WT and E-FABP mice was shaved and treated with or without 17 nmol TPA for 24 hours before collection for analyses of different types of cytokines and chemokines using quantitative PCR. a–h, relative expression of IL-6 (a), TNFα (b), IL-10(c), TGF1β (d), IL-1α (e), IL-1β (f), IFNβ (g) and IFNλ (h) was shown in untreated and treated WT and E-FABP−/− mice (n=4/group). Data are representative of three experiments. *, p<0.05 and **, p<0.01 as compared between WT and E-FABP−/− mice. (i,j) Analysis of expression of IFNβ and IFNλ in skin tissue of WT (i) and E-FABP−/− mice (j) treated with TPA for 7 days by confocal microscopy (IFNs: green; nucleus: blue; IFN producing cells: white arrows, scale bar = 10μM).

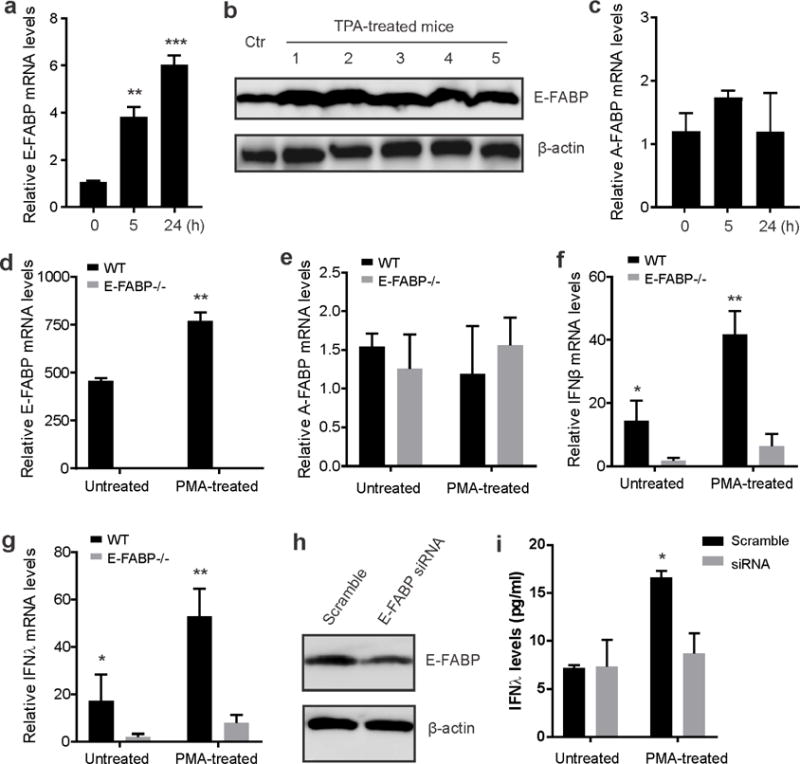

E-FABP is critical in PMA-induced production of IFNβ and IFNλ in keratinocytes

We noticed that TPA treatment significantly induced skin thickness. As E-FABP is the predominant FABP in skin (Zhang et al., 2015), we speculated that TPA treatment might impact E-FABP expression. To this end, TPA-treated mouse dorsal skin tissues were collected at different time points for analysis of FABP expression. We found that both mRNA and protein levels of E-FABP were significantly increased in response to TPA treatment (Figure 3A, 3B). In contrast, A-FABP expression levels in skin were much lower and did not change in response to TPA treatment (Figure 3C), suggesting a critical role of E-FABP, but not A-FABP, in TPA-induced skin pathogenesis. To confirm the essential role of E-FABP in IFN expression, we isolated keratinocytes from epidermis of WT and E-FABP−/− mice and measured FABP and IFN expression in the presence or absence of PMA stimulation. Similar to in vivo TPA treatment, E-FABP, but not A-FABP, was significantly upregulated by PMA stimulation in vitro (Figure 3D, 3E). Strikingly, ablation of E-FABP expression in keratinocytes diminished the expression of IFNβ and IFNλ in primary keratinocytes under both PMA-treated and untreated conditions (Figure 3F, 3G). To further verify the causal effect of E-FABP in IFN production, we knocked down E-FABP expression in the MPEK keratinocyte cell line (derived from the same C57/B6 genetic background) using siRNA (Figure 3H) and demonstrated that E-FABP silencing significantly blocked PMA-induced IFNλ production in keratinocytes (Figure 3I). Of note, IFNβ levels were too low to be detected under the same condition. Altogether, our data indicate that E-FABP expression in keratinocytes is essential for IFNβ and IFNλ production under TPA-induced conditions, thereby influencing chemically induced skin tumorigenesis.

Figure 3. TPA treatment of skin upregulates E-FABP expression and E-FABP-dependent production of IFNβ and IFNλ.

(a,b) Analyses of E-FABP expression in skin treated with/without TPA at the indicated time points by qPCR (a) or 3 days by Western blotting (b). c, Real-time PCR analysis of A-FABP mRNA expression in skin treated with or without TPA for different time points. d–g, Analysis of the expression of E-FABP (d), A-FABP (e), IFNβ (f) and IFNλ (g) in primary skin keratinocytes treated with or without PMA for 24 hours by quantitative real-time PCR (n=6/group). h, Western blotting analysis of E-FABP expression in MPEK keratinocytes transfected with scramble or E-FABP siRNA. i, Measurement of IFNλ levels in the supernatants of siRNA-transfected MPEK keratinocytes treated with/without PMA for 6 hours. Data are representative of three experiments (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01).

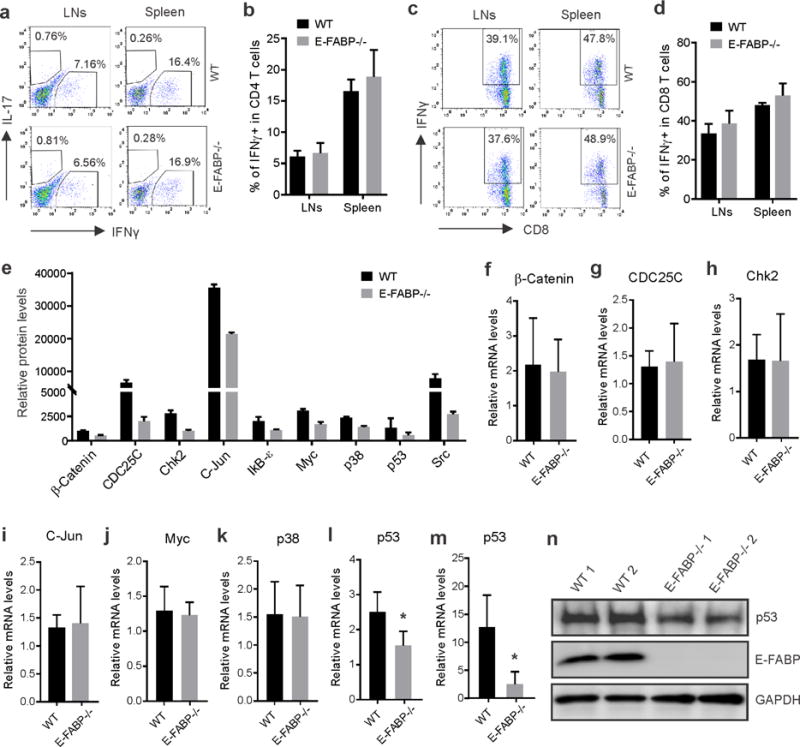

E-FABP deficiency suppresses p53 expression in keratinocytes

To determine how E-FABP expression affected skin tumorigenesis in vivo, we focused on both extrinsic immune surveillance effects and tumor cell intrinsic factors. We first analyzed immune cell phenotypes in tumor-bearing WT and E-FABP−/− mice. As shown in supplementary Table S1, E-FABP deficiency did not show any apparent phenotypic changes of immune cell populations in peripheral immune organs. When we further analyzed IFNγ production in T cells, we did not find any significant alterations in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells between WT and E-FABP−/− mice (Figure 4A–4D). It appeared that adaptive T cell responses did not apparently contribute to the observed tumor differences between WT and E-FABP−/− mice. To investigate if E-FABP deficiency affected intrinsic tumor signals, we collected tumor samples from WT and E-FABP−/− mice and performed tumor signaling antibody arrays. Among the 250 cancer signaling proteins, we found 9 proteins, including the tumor suppressive p53 protein, with > 2 fold upregulation in tumors from WT mice as compared to E-FABP−/− mice (Figure 4E, supplementary Table S2). These data suggest that E-FABP deficiency may lead to the differential expression of these cancer signaling proteins, thus contributing to the accelerated tumorigeneses in E-FABP−/− mice.

Figure 4. E-FABP deficiency is associated with reduced p53 expression in keratinocytes.

a–d, Draining lymph nodes (LNs) and spleen were collected from DMBA/TPA-treated tumor bearing mice and analyzed for IFNγ and IL-17 production by gating on CD4+ T cells (a) and IFNγ production in CD8+ T cells (c) by flow intracellular staining. Average percentage of IFNγ positive cells in CD4+ and CD8+ cells was shown in b and d, respectively (n=4/group). e, Cancer signaling proteins with relative fold > 2 between WT and E-FABP−/− skin tumors were shown by protein array analysis. f–l, qPCR analysis of relative expression of β-catenin (f), CDC25c (g), Chk2 (h), C-Jun (i), Myc (j), p38 (k) and p53 (l), in skin of naïve WT and E-FABP−/− mice. m, qPCR analysis of relative p53 levels in primary keratinocytes from WT and E-FABP−/− mice after PMA treatment for 24 hours (n=3/group, *p<0.05). n, Western blotting analysis of p53 expression in skin cell lysates after anti-p53 immunoprecipitation. The supernatants after p53-immunoprecipitation were directly analyzed for the expression of E-FABP and GAPDH.

To assess whether E-FABP deficiency in keratinocytes per se or whether secondary changes due to tumor development were responsible for the differential cancer signaling proteins, we compared transcriptional levels of these proteins in skin tissues of naïve WT and E-FABP−/−mice. Interestingly, among the 7 proteins with detectable transcripts, including β-catenin, CDC25c, Chk2, c-Jun, Myc, p38 and p53, we only found that relative levels of p53 mRNA were significantly reduced when E-FABP was genetically deleted (Figure 4F–4L). The reduced mRNA and protein levels of p53 in E-FABP−/− mice were confirmed in PMA-stimulated primary keratinocytes (Figure 4M, 4N). In contrast, E-FABP deficiency did not decrease the expression of other proteins in keratinocytes after PMA stimulation (supplementary Figure S3). It is very likely that E-FABP deficiency predisposes mice to skin tumorigenesis due to the reduced expression of p53 in keratinocytes.

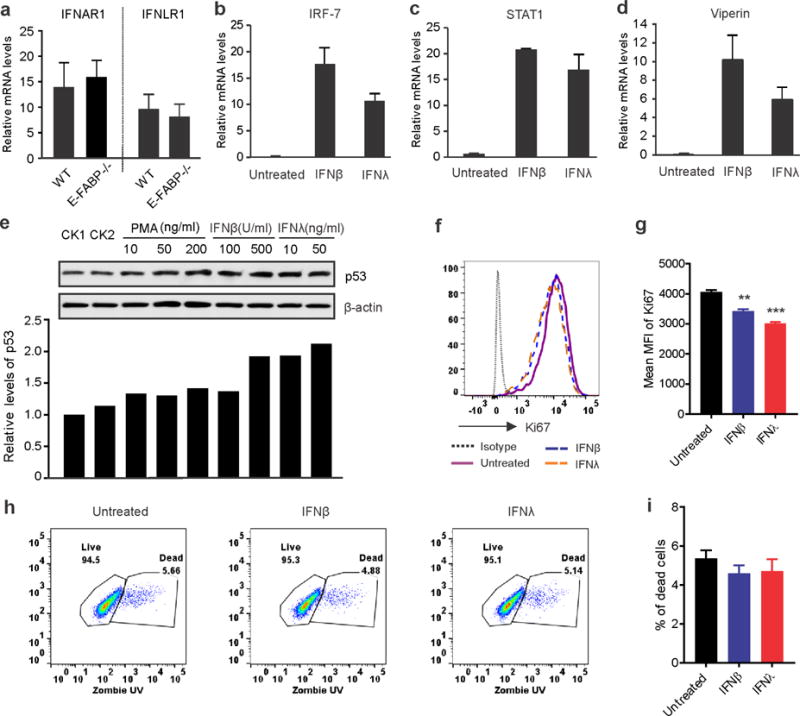

IFNβ and IFNλ increase p53 expression in keratinocytes and inhibit their proliferation

It has been previously demonstrated that type I IFNs induced p53 gene transcription and protein expression for tumor suppression and antiviral defense (Takaoka et al., 2003). Given the above observations that E-FABP−/−keratinocytes exhibited impaired IFNβ/λ production and reduced p53 expression, we wondered if IFNβ and IFNλ directly induced activation of p53 and inhibited proliferation of keratinocytes. IFNβ and IFNλ function through IFNAR1 and IFNLR1, respectively. We first measured the expression of IFNAR and IFNLR of WT and E-FABP−/−mice and found that E-FABP deficiency did not affect IFN receptor expression in the skin tissue (Figure 5A). Upon treatment with IFNβ and IFNλ, MPEK keratinocytes exhibited strong IFN-induced responses, including upregulation of IRF-7, STAT1 and Viperin (Figure 5B–5D), which were consistent with anti-tumor signaling induced by IFNβ/λ (Pομιευ−Mουρεζ ετ αλ., 2006). Most importantly, treatment with IFNβ or IFNλ was able to induce p53 upregulation in MPEK keratinocytes (Figure 5E). Consistent with other studies showing p53 as a brake on cell proliferation (Crochemore et al., 2002), we assessed keratinocyte proliferation by measuring Ki67 expression with flow cytometric staining and showed that IFN treatment significantly inhibited MPEK keratinocyte proliferation as compared to untreated controls (Figure 5F, 5G). Notably, IFNβ and IFNλ treatment did not induce apparent cell death of MPEK keratinocytes (Figure 5H, 5I). When primary keratinocytes from WT and E-FABP−/− mice were treated with IFNβ and IFNλ, respectively, they exhibited similar responses as MPEK cells, suggesting that E-FABP deficiency does not appear to affect IFN-induced responses in primary keratinocytes (supplementary Figure S4A–S4C). Taken together, our data suggest that E-FABP expression in keratinocytes promotes the production of IFNβ and IFNλ, which upregulate tumor suppressor p53, therefore suppressing skin tumor development.

Figure 5. IFNβ and IFNλ induce p53 expression in keratinocytes and inhibit their proliferation.

a, qPCR analysis of IFNAR1 and IFNLR1 receptor expression in skin of naïve WT and E-FABP−/− mice. b–d, Analysis of expression of IRF-7 (b), STAT1 (c) and Viperin (d) in MPEK keratinocytes treated with IFNβ (500U/ml) or IFNλ (50ng/ml) for 8 hours. e, Western blotting analysis of p53 expression in MPEK keratinocytes stimulated with indicated concentrations of PMA, IFNβ and IFNλ. Relative protein levels are shown in the low panel. f–i, Flow cytometric analyses of Ki67 expression (f) and cell death (h) of MPEK keratinocytes treated with/without IFNβ or IFNλ. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) and average percentage of dead cells are shown in panel g and i, respectively. Results are representative of three times of experiments. (**, p<0.01, ***, p<0.001).

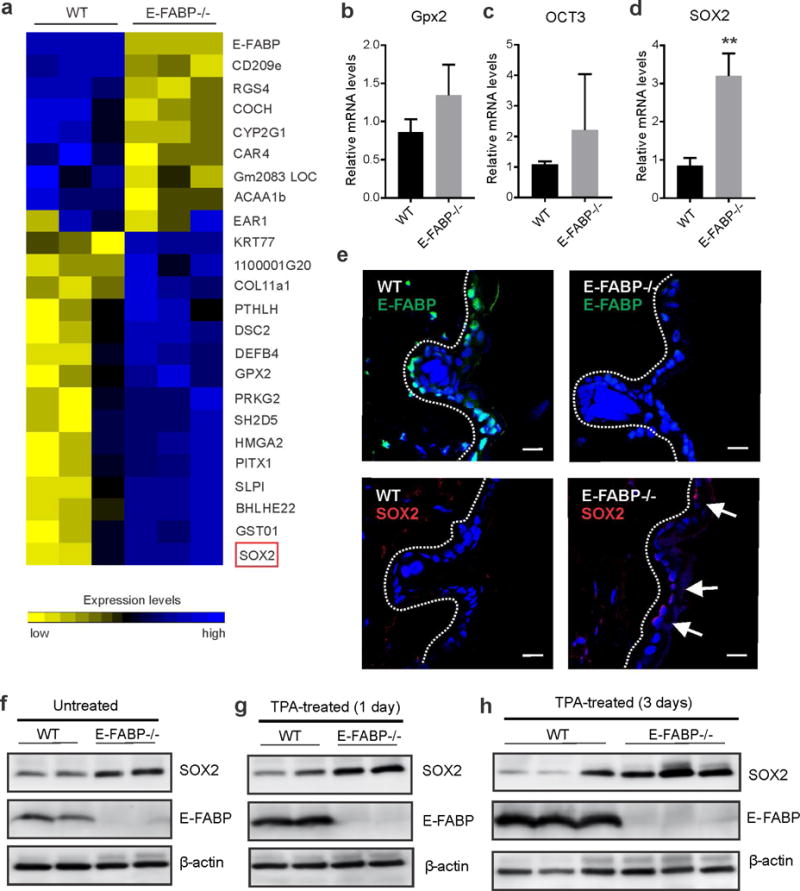

E-FABP deficiency is associated with upregulation of SOX2

It is well known that p53 suppresses tumor development by targeting different genes and pathways involved in cell growth arrest, senescence, death and angiogenesis (Wang and Sun, 2010). To further dissect the molecular mechanisms by which E-FABP expression provided a protective role against skin tumorigenesis, we performed gene microarray analysis using tumors from WT and E-FABP−/− mice. Of note, genes encoding cancer stemness markers (e.g. SOX2) were among the most upregulated genes in the E-FABP−/− tumors (Figure 6A, Supplementary Table S3). Using quantitative real-time PCR, we confirmed that SOX2 expression was significantly upregulated in the E-FABP−/− keratinocytes (Figure 6B–6D). With confocal analysis, we found that E-FABP was highly expressed in the epidermis of WT mice. Interestingly, when E-FABP was absent in the epidermis, SOX2 expression was upregulated at the basolateral surface close to the dermis (Figure 6E). Moreover, we observed consistent SOX2 upregulation in E-FABP−/− skin as compared to WT skin under either untreated or TPA treated conditions (Figure 6F–6H), further corroborating that E-FABP deficiency is associated with elevated levels of SOX2 expression in keratinocytes. Given the observations that SOX2 controls tumor initiation in SCC and that the p53 pathway inhibits the expression of SOX2 (Wang and Sun, 2010; Boumahdi et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016), our data reveal a previously unreported mechanism wherein E-FABP regulates IFN/p53/SOX2 axis in keratinocytes for prevention of skin tumorigenesis.

Figure 6. SOX2 expression is upregulated in skin of E-FABP deficiency mice.

a, Heatmap of differentially expressed genes with fold >3 in tumors from WT and E-FABP−/−mice. b–d, Real-time PCR analysis of expression of Gpx2 (b), OCT3 (c) and SOX2 (d) in primary keratinocytes from WT and E-FABP−/− mice (n=3/group, **, p<0.01 as compared to WT mice). e, Confocal microscopic analysis of expression of E-FABP (green color) and SOX2 (red color) in keratinocytes of skin epidermis from WT and E-FABP deficiency mice (scale bar = 10μM). f–h, Western blotting analysis of SOX2 and E-FABP expression in skin of untreated naïve mice (f), mice treated with TPA for 1 day (g) and mice treated with TPA for 3 days (h).

Discussion

Although E-FABP is highly expressed in skin epidermis, the biological functions of E-FABP in skin remain largely unexplored. Using congenic E-FABP−/− and WT mice, in the current study we demonstrate that E-FABP expression is critical in suppression of DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumorigenesis. Mechanistically, E-FABP expression in skin of WT mice promotes IFNβ and IFNλ production and responses, accompanied by upregulated p53 expression and decreased SOX2 expression as compared to E-FABP−/− mice. Thus, E-FABP represents a previously unknown molecular mechanism by which the host maintains skin homeostasis and prevents environmental factor-induced skin tumor development.

The FABP family consists of 9 members that bind hydrophobic lipid ligands (e.g. endogenous or exogenous long-chain FAs and their derivatives) and coordinate their transportation, metabolism and functions (Hertzel et al., 2006; Hotamisligil and Bernlohr, 2015). Due to the tightly-regulated patterns of tissue distribution, FABPs are named according to the tissue where they are predominantly distributed. For example, E-FABP and A-FABP are highly expressed in epidermis and adipose tissue, respectively. Considering their FA binding characteristics, FABPs are believed to play important roles in cells responsible for lipid uptake, storage and those that use lipids as a major energy source, such as macrophages, adipocytes, memory T cells, etc (Nieman et al., 2011; Makowski et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2017). Skin protects the host against environmental insults by providing an effective physical barrier, among which lipid synthesis, composition and transportation are critical in maintaining normal skin integrity and function. E-FABP is the predominant FABP member expressed in keratinocytes (Zhang et al., 2015). However, the role of E-FABP in keratinocytes, especially in SCC development, is unclear. Here, we provide evidence showing that E-FABP expression in skin is essential in inhibition of chemically induced skin tumorigenesis. Notably, A-FABP is also expressed in skin, although to a lesser extent, A-FABP expression does not appear to play a significant role in skin tumorigenesis.

Lipids in keratinocytes are composed of free fatty acids, cholesterol and ceramides, among which polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are essential for skin structural integrity and normal skin barrier function (HANSEN et al., 1958; Pappas, 2009). As E-FABP binds different dietary FAs with a high affinity for PUFAs (Lee et al., 2015), keratinocytes deficient in E-FABP exhibit reduced incorporation of PUFAs, including linoleic acids (Ogawa et al., 2011). We also noticed that skin epidermis was thinner in E-FABP−/− mice when compared to WT mice. It is worth noting that studies from our group and others have shown that PUFAs taken up by macrophages or other types of cells promote the formation of lipid droplets, which function as a platform for the production of type I IFNs (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017; Mei et al., 2011; Hinson and Cresswell, 2009), thus, it was not surprising that we observed a reduced production of both IFNβ and IFNλ in E-FABP−/− keratinocytes. However, the restrictive expression pattern of IFNλ receptors on epithelial cells suggests its unique role in skin defense.

As immune sentinels, keratinocytes can discriminate pathogens, sense danger signals and induce immune responses (Nestle et al., 2009). For example, keratinocytes can abundantly produce IFNβ in psoriasis and during wound healing (Zhang et al., 2016), which is consistent with our data showing TPA/PMA stimulation upregulated IFNβ production in primary keratinocytes. However, we noticed that resting/unstimulated keratinocytes do not produce detectable levels of IFNβ. In contrast, IFNλ is constitutively produced by resting keratinocytes and can be upregulated during external stimuli, indicating a unique role of IFNλ in maintaining skin homeostasis. Given the observations that IFNβ induces p53 gene transcription and protein production for anti-tumor and anti-viral defense (Takaoka et al., 2003), we speculated that IFNλ might exert similar functions in inducing the p53 response. Indeed, we demonstrate that IFNλ treatment of keratinocytes upregulates p53 protein, which explains why naive E-FABP−/− mice exhibit reduced expression of p53 as compared to naïve WT mice. Moreover, E-FABP has been shown to promote keratinocyte differentiation through inducing expression of keratin 1 and involucrin (Dallaglio et al., 2013; Ogawa et al., 2011), our studies suggest that E-FABP is able to function via IFNλ/p53 pathway to maintain normal cycling of keratinocytes under physiologic conditions and to prevent keratinocyte oncogenic transformation due to environmental insults.

Given the numerous targets of p53-regulating genes for tumor suppression, we analyzed the differentially expressed genes between WT and E-FABP−/− tumors to identify the potential targets mediating E-FABP/p53 protective effects. Interestingly, SOX2 was the most upregulated gene expressed in E-FABP−/− tumors. As a transcription factor, SOX2 has been shown to be essential in maintenance of self-renewal and pluripotency of stem cells (Rizzino, 2009). Accumulated evidence also demonstrates that SOX2 is a key upregulated oncogene promoting squamous cell carcinoma in skin, lung, colon and breast (Tani et al., 2007; Hussenet et al., 2010; Piva et al., 2014; Boumahdi et al., 2014). More interestingly, recent studies report that the p53-dependent pathway directly controls a critical check-point of SOX2-mediated glial cell reprogramming and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (Brosh et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016). In addition, we also observed that E-FABP deficiency is associated with other cancer stemness markers, such as Nanog, in the skin tissue before and after PMA treatment (data not shown). Integration of our observations and documented research suggests that E-FABP enhancement of p53 pathway inhibits SOX2 expression in keratinocytes, thus reducing chemical-induced skin tumorigenesis.

In summary, our studies demonstrate a previously unknown function of E-FABP in skin tumor prevention through regulating IFN-p53/SOX2 pathway, indicating that E-FABP expression in skin is critical in host against chemical-induced tumorigenesis. Thus, targeting E-FABP and related signaling molecules may provide strategies for skin cancer prevention and immunotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Mice deficient for E-FABP or A-FABP were generated as previously described (Maeda et al., 2003; Hotamisligil et al., 1996). For the skin tumorigenesis model, 6 to 8 week old male wild type (WT), E-FABP−/− or A-FABP−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) were used for application of DMBA and TPA. Due to the carcinogenic properties, DMBA and TPA were applied strictly following the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). See detailed DMBA/TAP-induced skin tumors and skin cell preparation in the supplementary materials.

Culture and treatment of keratinocytes

The mouse keratinocyte cell line, MPEK, was purchased from ZenBio, Inc. Cells were cultured and propagated in CnT-07 medium (ZenBio, Inc.). These cells were treated with different concentrations of PMA, recombinant mouse IFN-β (100) (Biolegend, cat#: 581302) or recombinant mouse IFN-λ3 (R&D System, cat#: 1789-ML-025/CF), respectively, in vitro for 7 or 14 hours. For primary keratinocytes isolated from WT or KO mice, R5 (RPMI1640 supplemented with 5% FBS and 20 μg/ml gentamicin) was used for short-term culture. Complete minimum essential medium (MEM) or CnT-07 medium was used for overnight culture.

Flow cytometry and confocal analyses

Flow cytometry and confocal analyses were performed as previously described (Rao et al., 2015). See detailed antibody and clone information in the supplementary materials.

Quantitative real-time PCR and gene expression microarray

For real-time quantitative PCR and microarray analyses, total RNA from cells was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The cDNAs were synthesized using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix using ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR Systems or StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA levels were determined using HPRT1 as a reference gene. Primer sequences are listed in supplementary table S4. Gene expression microarray was performed at the Gene Expression Core at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. The assigned gene expression omnibus (GEO) accession number was GSE109583.

Western blotting and protein array

Western blotting was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). Anti-p53 antibody (FL-393 and sc-98, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SOX2 antibody (D-9, cat#sc-398254, Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-E-FABP antibody (cat#AF1476, R&D systems), and anti-β-actin antibody (2F1-1, cat#643802, Biolegend), were used for overnight incubation (binding). For analysis of p53 expression in primary keratinocytes, skin lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p53 antibody (FL-393) before p53 immunoblotting (sc-98). Skin tumors from WT and E-FABP−/−mice (n=3/group) were analyzed using the array for tumor signaling protein and phosphorylation (Full Moon BioSystems, Inc.).

E-FABP knockdown with siRNAs

Duplex small interfering RNAs (dsiRNAs) targeting the coding region of E-FABP were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. For E-FABP knockdown in the MPEK keratinocyte cell line, cells were transfected with 20 nM siRNA using Oligofectamine (Life Technologies) when 50% cells confluency was reached. Transfected cells were then treated 24h later.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction or Mann Whitney test was used for data analyses. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partially by the Hormel Foundation and National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD) grants R01CA177679, R01CA180986.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Abel EL, Angel JM, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumahdi S, Driessens G, Lapouge G, Rorive S, Nassar D, Le MM, et al. SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature13305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosh R, Assia-Alroy Y, Molchadsky A, Bornstein C, Dekel E, Madar S, et al. p53 counteracts reprogramming by inhibiting mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:312–320. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HM, Tanaka N, Mitani Y, Oda E, Nozawa H, Chen JZ, et al. Critical role for constitutive type I interferon signaling in the prevention of cellular transformation. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochemore C, Michaelidis TM, Fischer D, Loeffler JP, Almeida OF. Enhancement of p53 activity and inhibition of neural cell proliferation by glucocorticoid receptor activation. FASEB J. 2002;16:761–770. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0577com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaglio K, Marconi A, Truzzi F, Lotti R, Palazzo E, Petrachi T, et al. E-FABP induces differentiation in normal human keratinocytes and modulates the differentiation process in psoriatic keratinocytes in vitro. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:255–261. doi: 10.1111/exd.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSEN AE, HAGGARD ME, BOELSCHE AN, ADAM DJ, WIESE HF. Essential fatty acids in infant nutrition. III. Clinical manifestations of linoleic acid deficiency. J Nutr. 1958;66:565–576. doi: 10.1093/jn/66.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzel AV, Smith LA, Berg AH, Cline GW, Shulman GI, Scherer PE, et al. Lipid metabolism and adipokine levels in fatty acid-binding protein null and transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E814–E823. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00465.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson ER, Cresswell P. The antiviral protein, viperin, localizes to lipid droplets via its N-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20452–20457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911679106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Bernlohr DA. Metabolic functions of FABPs-mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:592–605. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Johnson RS, Distel RJ, Ellis R, Papaioannou VE, Spiegelman BM. Uncoupling of obesity from insulin resistance through a targeted mutation in aP2, the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein. Science. 1996;274:1377–1379. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussenet T, Dali S, Exinger J, Monga B, Jost B, Dembele D, et al. SOX2 is an oncogene activated by recurrent 3q26.3 amplifications in human lung squamous cell carcinomas. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CJ. Multistep skin cancer in mice as a model to study the evolution of cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:460–473. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapouge G, Beck B, Nassar D, Dubois C, Dekoninck S, Blanpain C. Skin squamous cell carcinoma propagating cells increase with tumour progression and invasiveness. EMBO J. 2012;31:4563–4575. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Kim JE, Do H, Kim RO, Lee SG, Park HH, et al. Structural basis for the ligand-binding specificity of fatty acid-binding proteins (pFABP4 and pFABP5) in gentoo penguin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;465:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter U, Eigentler T, Garbe C. Epidemiology of skin cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;810:120–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0437-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Reynolds JM, Stout RD, Bernlohr DA, Suttles J. Regulation of Th17 differentiation by epidermal fatty acid-binding protein. J Immunol. 2019;182:7625–7633. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund AW, Medler TR, Leachman SA, Coussens LM. Lymphatic Vessels, Inflammation, and Immunity in Skin Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:22–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen P, Rasmussen HH, Leffers H, Honore B, Celis JE. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel keratinocyte protein (psoriasis-associated fatty acid-binding protein [PA-FABP]) that is highly up-regulated in psoriatic skin and that shares similarity to fatty acid-binding proteins. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:299–305. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12616641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Uysal KT, Makowski L, Gorgun CZ, Atsumi G, Parker RA, et al. Role of the fatty acid binding protein mal1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2003;52:300–307. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski L, Brittingham KC, Reynolds JM, Suttles J, Hotamisligil GS. The fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, coordinates macrophage cholesterol trafficking and inflammatory activity. Macrophage expression of aP2 impacts peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and IkappaB kinase activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12888–12895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei S, Ni HM, Manley S, Bockus A, Kassel KM, Luyendyk JP, et al. Differential roles of unsaturated and saturated fatty acids on autophagy and apoptosis in hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:487–498. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SM, Holt VV, Malpass LR, Hines IN, Wheeler MD. Fatty acid-binding protein 5 limits the anti-inflammatory response in murine macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestle FO, Di MP, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, Ladanyi A, Buell-Gutbrod R, Zillhardt MR, et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med. 2011;17:1498–1503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa E, Owada Y, Ikawa S, Adachi Y, Egawa T, Nemoto K, et al. Epidermal FABP (FABP5) regulates keratinocyte differentiation by 13(S)-HODE-mediated activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:604–612. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owada Y, Suzuki I, Noda T, Kondo H. Analysis on the phenotype of E-FABP-gene knockout mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A, Navarro M, Suarez-Cabrera C, Alameda JP, Casanova ML, Paramio JM, et al. Protective role of p53 in skin cancer: Carcinogenesis studies in mice lacking epidermal p53. Oncotarget. 2016;7:20902–20918. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Tian T, Park CO, Lofftus SY, Mei S, Liu X, et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature. 2017;543:252–256. doi: 10.1038/nature21379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas A. Epidermal surface lipids. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:72–76. doi: 10.4161/derm.1.2.7811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piva M, Domenici G, Iriondo O, Rabano M, Simoes BM, Comaills V, et al. Sox2 promotes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:66–79. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao E, Zhang Y, Zhu G, Hao J, Persson XM, Egilmez NK, et al. Deficiency of AMPK in CD8+ T cells suppresses their anti-tumor function by inducing protein phosphatase-mediated cell death. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7944–7958. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzino A. Sox2 and Oct-3/4: a versatile pair of master regulators that orchestrate the self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2009;1:228–236. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu-Mourez R, Solis M, Nardin A, Goubau D, Baron-Bodo V, Lin R, Massie B, Salcedo M, Hiscott J. Distinct roles for IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-3 and IRF-7 in the activation of antitumor properties of human macrophages. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10576–10585. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch J, McDermott L. Structural and functional analysis of fatty acid-binding proteins. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S126–S131. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800084-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A, Hayakawa S, Yanai H, Stoiber D, Negishi H, Kikuchi H, et al. Integration of interferon-alpha/beta signalling to p53 responses in tumour suppression and antiviral defence. Nature. 2003;424:516–523. doi: 10.1038/nature01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani Y, Akiyama Y, Fukamachi H, Yanagihara K, Yuasa Y. Transcription factor SOX2 up-regulates stomach-specific pepsinogen A gene expression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Su Z, Tai W, Zou Y, Xu XM, Zhang CL. The p53 Pathway Controls SOX2-Mediated Reprogramming in the Adult Mouse Spinal Cord. Cell Rep. 2016;17:891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Sun Y. Targeting p53 for Novel Anticancer Therapy. Transl Oncol. 2010;3:1–12. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LJ, Sen GL, Ward NL, Johnston A, Chun K, Chen Y, et al. Antimicrobial Peptide LL37 and MAVS Signaling Drive Interferon-beta Production by Epidermal Keratinocytes during Skin Injury. Immunity. 2016;45:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li Q, Rao E, Sun Y, Grossmann ME, Morris RJ, et al. Epidermal Fatty Acid binding protein promotes skin inflammation induced by high-fat diet. Immunity. 2015;42:953–964. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Rao E, Zeng J, Hao J, Sun Y, Liu S, et al. Adipose Fatty Acid Binding Protein Promotes Saturated Fatty Acid-Induced Macrophage Cell Death through Enhancing Ceramide Production. J Immunol. 2017;198:798–807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sun Y, Rao E, Yan F, Li Q, Zhang Y, et al. Fatty acid-binding protein E-FABP restricts tumor growth by promoting IFN-beta responses in tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2986–2998. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.