Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To provide updated prevalence data on obesity trends among US children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years from a nationally representative sample.

METHODS:

We used the NHANES for years 1999 to 2016. Weight status was determined by using measured height and weight from the physical examination component of the NHANES to calculate age- and sex-specific BMI. We report the prevalence estimates of overweight and obesity (class I, class II, and class III) by 2-year NHANES cycles and compared cycles by using adjusted Wald tests and linear trends by using ordinary least squares regression.

RESULTS:

White and Asian American children have significantly lower rates of obesity than African American children, Hispanic children, or children of other races. We report a positive linear trend for all definitions of overweight and obesity among children 2–19 years old, most prominently among adolescents. Children aged 2 to 5 years showed a sharp increase in obesity prevalence from 2015 to 2016 compared with the previous cycle.

CONCLUSIONS:

Despite previous reports that obesity in children and adolescents has remained stable or decreased in recent years, we found no evidence of a decline in obesity prevalence at any age. In contrast, we report a significant increase in severe obesity among children aged 2 to 5 years since the 2013–2014 cycle, a trend that continued upward for many subgroups.

The prevalence of childhood obesity has increased dramatically among all age groups since 1988.1 Over the past several years, some researchers have reported stabilization in the obesity prevalence overall among youth1–3 and decreases in 2- to 5-year-old children.3,4 However, others report no decrease in any age group since 19995,6 but rather a sharp increase in the prevalence of severe obesity, particularly among adolescents and non-Hispanic African American children.5

Previously, severe obesity had been defined as having a BMI >99th percentile.7 Recent analyses suggest that BMI SD scores (z scores) poorly reflect adiposity among children and adolescents with severe obesity.8–10 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend using a relative BMI measure to describe youth with severe obesity.11 A new classification system recognizes BMI ≥95th percentile as class I obesity, BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile as class II obesity, and BMI ≥140% of the 95th percentile as class III obesity. Class II and III obesity are strongly associated with greater cardiovascular and metabolic risk.12

Despite intense focus on reducing the US childhood obesity epidemic over the past 2 decades, our progress remains unclear. Ongoing surveillance is critical to gauging population-level prevalence changes that result from overarching policy or public health changes. Our objective is to provide the most up-to-date data on the national prevalence of all obesity classes, including severe obesity, among children and adolescents in the United States. A recent CDC report has provided a summary statement on these recent trends.13 We build on that report here by providing prevalence rates for severe obesity, more specific age subgroups, and adding context to these trends by providing a long-term prevalence report. We report youth obesity and severe obesity prevalence from the most recent cycle of the NHANES (2015–2016) and provide long-term trends from the NHANES 1999–2016 cycle.

METHODS

We are using methods and analyses that are similar to those of previous studies,5,6,12 which are detailed in brief as follows.

Data

The data source is the NHANES for years 1999–2016. The NHANES is a stratified, multistage probability sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population. Although the NHANES contains multiple components, we used the in-home interview and physical examination here, including measured height and weight. We included all children aged 2 to 19 years. For the present analysis, we used only deidentified secondary data, so it was therefore deemed exempt from further review by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board under federal regulation 45CFR§46.101(b).

Measures

Weight status is directly measured by using height and weight measurements gathered from the physical examination component of NHANES to calculate age- and sex-specific BMI. We defined overweight and obesity, hereby referred to as class I obesity, to contrast with class II and class III (more severe forms of obesity) by using CDC criteria, which define overweight as age- and sex-specific BMI ≥85th percentile and class I obesity as BMI ≥95th percentile.14 We defined class II and class III obesity to be consistent with previous reports,6,12,15 with class II obesity defined as a BMI >120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex or a BMI of ≥35 (whichever is lower) and class III obesity defined as a BMI ≥140% of the 95th percentile for age and sex or a BMI of ≥40 or greater (whichever is lower). These categories were not mutually exclusive; for example, any children or adolescents meeting the criteria for overweight include all the children and adolescents with a BMI ≥85th percentile (even if they are also in the ≥95th percentile).

For years 1999–2010, the NHANES characterized race and ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic, and other race and/or ethnicity. Beginning in 2011, the NHANES included an Asian American oversample, allowing for a more detailed characterization of this group. We include estimates for Asian Americans in years when this information is available. Before 2011, the inclusion of Asian Americans in the other race category made that category different from the other race category of 2011–2016, when Asian Americans were categorized separately. Therefore, we present other race separately for years when Asian Americans were included in the category and present them as their own category from 2011 to 2016, when they were oversampled.

Statistical Approach

We report the prevalence estimates of overweight and each obesity definition by 2-year NHANES cycles. To test the trends from 1999 to 2016, we report P values from ordinary least squares regression, with the NHANES year as a continuous variable predicting obesity and severe obesity prevalence. To compare the 2 most recent NHANES cycles, we present P values from adjusted Wald tests to compare differences between the most recent cycles, 2013–2014 and 2015–2016. We adjusted all analyses for the complex survey design of the NHANES, including strata, primary sampling units, and probability weights, by using the survey estimation commands in Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Readers should use the following information as guidance when interpreting our findings. We present results from multiple significance tests but do not make any adjustments for multiple testing, which reduces the chance of a type II error but increases the chance of a type I error. Readers should consider the chance for both type I and type II errors. To reduce the chance of a type II error (indicating as significant a relationship that does not exist), we present all ad hoc data without choosing only those that are significant. We include P values for reference but encourage readers not to focus on P < .05 and instead to consider the body of data. In the supplemental appendices, we present confidence intervals (CIs) to allow readers to draw their own conclusions about more nuanced comparisons. The chance of a type I error (not identifying a relationship that does exist) should be considered, particularly in our comparisons between the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 cycles. Although the sample size allows for the identification of relatively small differences in the prevalence of the full sample, subgroup analyses should be considered more carefully. We have provided sample sizes throughout the tables to assist readers in their assessments.

RESULTS

Prevalence

Table 1 presents the prevalence of overweight and all classes of obesity by demographic characteristics in the most recent NHANES cycle, 2015–2016. Non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic children had higher prevalence rates of overweight and all classes of obesity compared with other races. Asian American children had markedly lower rates of overweight and all classes of obesity. The prevalence of overweight and obesity increased with age, with 41.5% of 16- to 19-year-old adolescents having obesity and 4.5% meeting criteria for class III obesity.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Children and Adolescents, 2015–2016

| Total | Overweight | Class I Obesity | Class II Obesity | Class III Obesity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3340 | n = 1213 | n = 652 | n = 213 | n = 73 | ||||||||||

| n | % | % | 95% CI | P | % | 95% CI | P | % | 95% CI | P | % | 95% CI | P | |

| Total | — | — | 35.1 | 31.9 to 38.4 | 18.5 | 15.8 to 21.2 | 6.0 | 4.3 to 7.6 | 1.9 | 1.0 to 2.9 | ||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| 2–5 y | 814 | 20.7 | 26.0 | 21.3 to 30.7 | .005 | 13.7 | 11.4 to 16.0 | .239 | 1.8 | 0.6 to 3.0 | 0.006 | 0.2 | −0.1 to 0.4 | .059 |

| 6–8 y | 655 | 17.2 | 32.8 | 27.1 to 38.5 | — | 18.8 | 13.1 to 24.5 | — | 5.1 | 3.2 to 7.1 | — | 1.4 | 0.5 to 2.3 | — |

| 9–11 y | 613 | 16.5 | 35.6 | 30.7 to 40.6 | — | 18.5 | 14.8 to 22.3 | — | 5.3 | 2.9 to 7.7 | — | 1.0 | 0.4 to 1.7 | — |

| 12–15 y | 675 | 24.9 | 38.7 | 32.7 to 44.7 | — | 20.6 | 15.6 to 25.6 | — | 7.5 | 4.2 to 10.8 | — | 2.2 | 0.9 to 3.4 | — |

| 16–19 y | 583 | 20.7 | 41.5 | 37.1 to 45.9 | — | 20.5 | 15.5 to 25.5 | — | 9.5 | 5.8 to 13.1 | — | 4.5 | 1.7 to 7.4 | — |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 1644 | 48.9 | 35.5 | 31.6 to 39.5 | .691 | 17.8 | 15.3 to 20.3 | .408 | 5.2 | 3.3 to 7.1 | 0.243 | 1.8 | 0.8 to 2.8 | .668 |

| Male | 1696 | 51.1 | 34.8 | 31.1 to 38.4 | — | 19.1 | 15.5 to 22.7 | — | 6.7 | 4.4 to 8.9 | — | 2.0 | 0.9 to 3.2 | — |

| Race | ||||||||||||||

| White | 925 | 51.9 | 29.9 | 27.4 to 32.4 | <.001 | 14.1 | 11.8 to 16.5 | <.001 | 3.9 | 2.8 to 5.0 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 0.2 to 2.0 | .001 |

| African American | 767 | 13.9 | 37.8 | 32.4 to 43.1 | — | 22.2 | 16.4 to 27.9 | — | 9.0 | 6.0 to 12.1 | — | 3.8 | 1.8 to 5.9 | — |

| Hispanic | 1126 | 23.9 | 45.9 | 41.8 to 50.0 | — | 25.8 | 22.6 to 29.0 | — | 9.1 | 6.7 to 11.6 | — | 3.3 | 2.0 to 4.6 | — |

| Asian American | 288 | 4.7 | 23.2 | 17.8 to 28.7 | — | 10.7 | 6.8 to 14.6 | — | 1.4 | −0.3 to 3.1 | — | 0.0 | — | — |

| Other | 234 | 5.6 | 41.5 | 31.7 to 51.2 | — | 25.3 | 13.3 to 37.3 | — | 7.6 | 0.0 to 15.3 | — | 0.7 | −0.3 to 1.6 | — |

—, not applicable.

Trends in the 1999–2000 and 2015–2016 Cycles

Table 2 shows the prevalence of overweight and all classes of obesity by ordinal 2-year cycles (1999–2016) for females, males, and both sexes. A positive linear trend is significant for overweight (P = .003), class I obesity (P = .008), class II obesity (P = .019), and class III obesity (P < .001) for both sexes, with all ages combined. The increasing linear trend from 1999 to 2016 is most apparent among Hispanic females (Table 3). Similar to those of females, there are large increases in overweight and class II obesity among Hispanic males (Table 4). All 95% CIs are included in Supplemental Tables 5–9.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity From 1999 to 2016 by Sex and Age

| Both Sexes | Females | Males | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Overweight | Class I Obesity | Class II Obesity | Class III Obesity | Overweight | Class I Obesity | Class II Obesity | Class III Obesity | Overweight | Class I Obesity | Class II Obesity | Class III Obesity | ||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| n | % | % | % | % | n | % | % | % | % | n | % | % | % | % | |

| All ages | |||||||||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 4063 | 28.8 | 14.6 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 1992 | 27.5 | 14.6 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 2071 | 30.1 | 14.7 | 4.1 | 1.0 |

| 2001–2002 | 4305 | 29.9 | 15.2 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 2179 | 29.5 | 14.2 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 2126 | 30.3 | 16.2 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| 2003–2004 | 4016 | 33.8 | 17.1 | 5.2 | 1.6 | 2012 | 32.9 | 16.1 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 2004 | 34.6 | 18.1 | 5.4 | 1.6 |

| 2005–2006 | 4252 | 30.1 | 15.8 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 2138 | 29.7 | 15.3 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 2114 | 30.6 | 16.2 | 5.1 | 1.3 |

| 2007–2008 | 3281 | 31.7 | 17.0 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 1556 | 31.2 | 15.9 | 4.6 | 1.6 | 1725 | 32.1 | 17.9 | 5.5 | 1.6 |

| 2009–2010 | 3408 | 31.9 | 17.0 | 5.8 | 1.6 | 1631 | 30.4 | 15.0 | 5.1 | 1.5 | 1777 | 33.3 | 19.0 | 6.5 | 1.7 |

| 2011–2012 | 3355 | 32.0 | 16.9 | 5.8 | 2.1 | 1642 | 31.7 | 17.2 | 5.9 | 2.2 | 1713 | 32.2 | 16.7 | 5.8 | 2.0 |

| 2013–2014 | 3523 | 33.5 | 17.3 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 1729 | 33.3 | 17.2 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 1794 | 33.7 | 17.5 | 5.7 | 2.1 |

| 2015–2016 | 3340 | 35.1 | 18.5 | 6.0 | 1.9 | 1644 | 35.5 | 17.8 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 1696 | 34.8 | 19.1 | 6.7 | 2.0 |

| pa | .387 | .481 | .790 | .477 | .405 | .759 | .236 | .275 | .615 | .424 | .436 | .932 | |||

| pb | .003 | .008 | .019 | <.001 | .003 | .020 | .028 | .001 | .062 | .046 | .108 | .020 | |||

| Age 2–5 | |||||||||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 726 | 21.2 | 10.7 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 352 | 20.4 | 11.1 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 374 | 22.0 | 10.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| 2001–2002 | 795 | 22.4 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 412 | 21.7 | 9.9 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 383 | 23.2 | 10.4 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| 2003–2004 | 819 | 25.9 | 13.4 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 417 | 25.5 | 12.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 402 | 26.4 | 14.6 | 3.9 | 1.3 |

| 2005–2006 | 952 | 22.3 | 10.7 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 479 | 21.1 | 11.0 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 473 | 23.4 | 10.4 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| 2007–2008 | 885 | 20.9 | 10.3 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 396 | 21.1 | 10.7 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 489 | 20.6 | 9.8 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| 2009–2010 | 903 | 26.4 | 12.1 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 432 | 23.2 | 9.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 471 | 29.4 | 14.3 | 3.6 | 0.3 |

| 2011–2012 | 871 | 22.6 | 8.3 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 432 | 21.6 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 439 | 23.6 | 9.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 |

| 2013–2014 | 843 | 25.1 | 9.3 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 415 | 24.8 | 10.0 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 428 | 25.5 | 8.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| 2015–2016 | 814 | 26.0 | 13.7 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 396 | 25.9 | 13.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 418 | 26.0 | 14.2 | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| pa | .773 | .011 | .928 | .962 | .769 | .140 | .326 | .323 | .863 | .018 | .075 | .624 | |||

| pb | .131 | .992 | .420 | .294 | .229 | .851 | .750 | .933 | .281 | .868 | .341 | .258 | |||

| Age 6–8 | |||||||||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 534 | 29.7 | 14.9 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 241 | 25.6 | 14.0 | 2.9 | 0.4 | 293 | 33.1 | 15.8 | 3.2 | 0.4 |

| 2001–2002 | 596 | 30.8 | 15.1 | 6.3 | 1.2 | 309 | 27.9 | 12.0 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 287 | 33.8 | 18.4 | 8.7 | 1.9 |

| 2003–2004 | 490 | 30.0 | 15.8 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 261 | 26.7 | 13.6 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 229 | 33.1 | 17.8 | 3.3 | 1.4 |

| 2005–2006 | 553 | 25.3 | 13.1 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 274 | 22.4 | 12.6 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 279 | 28.2 | 13.7 | 3.6 | 1.3 |

| 2007–2008 | 608 | 31.4 | 17.3 | 5.1 | 1.1 | 305 | 29.9 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 303 | 32.9 | 20.3 | 6.4 | 1.3 |

| 2009–2010 | 597 | 30.8 | 17.6 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 282 | 32.7 | 17.5 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 315 | 29.2 | 17.6 | 4.4 | 1.1 |

| 2011–2012 | 654 | 30.8 | 16.9 | 6.0 | 2.5 | 304 | 32.4 | 19.9 | 5.4 | 1.8 | 350 | 29.6 | 14.5 | 6.5 | 3.0 |

| 2013–2014 | 674 | 30.5 | 15.7 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 320 | 29.4 | 13.3 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 354 | 31.5 | 17.9 | 3.3 | 0.6 |

| 2015–2016 | 655 | 32.8 | 18.8 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 321 | 34.2 | 19.4 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 334 | 31.6 | 18.2 | 5.3 | 1.1 |

| pa | .503 | 344 | .101 | .055 | .364 | 110 | .312 | .024 | .987 | .941 | .155 | .461 | |||

| pb | .379 | .135 | .555 | .206 | .041 | .050 | .339 | .091 | .458 | .798 | .990 | .673 | |||

| Age 9–11 | |||||||||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 514 | 31.7 | 16.4 | 3.8 | 0.6 | 265 | 30.5 | 16.4 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 249 | 33.0 | 16.3 | 3.5 | 0.7 |

| 2001–2002 | 569 | 33.5 | 17.0 | 5.9 | 1.4 | 275 | 36.5 | 17.8 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 294 | 30.8 | 16.2 | 7.3 | 2.1 |

| 2003–2004 | 492 | 44.8 | 22.1 | 6.9 | 1.5 | 258 | 49.6 | 22.1 | 6.6 | 1.3 | 234 | 40.3 | 22.1 | 7.2 | 1.6 |

| 2005–2006 | 561 | 33.5 | 18.2 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 290 | 32.4 | 16.8 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 271 | 34.6 | 19.6 | 5.0 | 0.8 |

| 2007–2008 | 589 | 39.7 | 22.1 | 6.5 | 0.9 | 297 | 40.2 | 21.8 | 6.6 | 0.5 | 292 | 39.1 | 22.4 | 6.3 | 1.3 |

| 2009–2010 | 616 | 35.1 | 18.7 | 5.8 | 1.7 | 310 | 31.8 | 14.3 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 306 | 38.4 | 23.3 | 7.2 | 1.1 |

| 2011–2012 | 614 | 38.0 | 18.7 | 7.7 | 1.4 | 314 | 38.1 | 18.6 | 7.4 | 1.5 | 300 | 37.9 | 18.8 | 8.1 | 1.3 |

| 2013–2014 | 620 | 36.1 | 20.2 | 5.9 | 1.8 | 309 | 35.1 | 18.9 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 311 | 37.3 | 21.6 | 5.9 | 2.2 |

| 2015–2016 | 613 | 35.6 | 18.5 | 5.3 | 1.0 | 320 | 27.8 | 14.0 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 293 | 43.8 | 23.3 | 5.2 | 1.2 |

| pa | .895 | .574 | .738 | .269 | .110 | .141 | .852 | .396 | .223 | .700 | .774 | .417 | |||

| pb | .654 | .493 | .410 | .240 | .138 | .420 | .464 | .059 | .036 | .068 | .702 | .779 | |||

| Age 12–15 | |||||||||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 1184 | 31.8 | 16.6 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 591 | 33.0 | 16.4 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 593 | 30.7 | 16.7 | 5.4 | 1.5 |

| 2001–2002 | 1191 | 31.4 | 16.8 | 5.8 | 0.8 | 639 | 32.3 | 16.9 | 5.3 | 1.0 | 552 | 30.6 | 16.7 | 6.2 | 0.6 |

| 2003–2004 | 1096 | 35.7 | 16.8 | 5.3 | 1.5 | 534 | 34.0 | 16.2 | 5.0 | 0.7 | 562 | 37.2 | 17.4 | 5.6 | 2.2 |

| 2005–2006 | 1058 | 34.6 | 18.1 | 6.8 | 1.3 | 531 | 37.0 | 19.6 | 7.5 | 1.1 | 527 | 32.5 | 16.7 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| 2007–2008 | 608 | 37.9 | 19.5 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 290 | 39.7 | 18.2 | 5.9 | 2.6 | 318 | 36.3 | 20.8 | 6.3 | 1.9 |

| 2009–2010 | 645 | 33.4 | 17.4 | 7.3 | 1.9 | 321 | 32.9 | 16.4 | 5.4 | 0.7 | 324 | 34.0 | 18.5 | 9.3 | 3.2 |

| 2011–2012 | 623 | 36.7 | 23.3 | 7.2 | 2.5 | 300 | 35.0 | 23.6 | 7.9 | 3.1 | 323 | 38.3 | 22.9 | 6.4 | 1.9 |

| 2013–2014 | 718 | 38.2 | 20.1 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 345 | 40.4 | 22.1 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 373 | 36.2 | 18.3 | 7.8 | 3.4 |

| 2015–2016 | 675 | 38.7 | 20.6 | 7.5 | 2.2 | 313 | 39.2 | 20.6 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 362 | 38.2 | 20.6 | 9.7 | 3.2 |

| pa | .906 | .889 | .686 | .386 | .852 | .792 | .775 | .286 | .643 | .554 | .464 | .880 | |||

| pb | .018 | .014 | .100 | .004 | .089 | .049 | .732 | .150 | .052 | .090 | .048 | .020 | |||

| Age 16–19 | |||||||||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 1105 | 30.4 | 15.0 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 543 | 28.6 | 15.4 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 562 | 32.2 | 14.5 | 6.6 | 1.8 |

| 2001–2002 | 1154 | 31.0 | 16.5 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 544 | 29.3 | 14.3 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 610 | 32.5 | 18.6 | 5.9 | 2.0 |

| 2003–2004 | 1119 | 33.8 | 18.3 | 7.3 | 2.8 | 542 | 31.1 | 17.4 | 7.8 | 4.0 | 577 | 36.3 | 19.2 | 6.9 | 1.5 |

| 2005–2006 | 1128 | 33.6 | 18.0 | 7.8 | 2.9 | 564 | 33.5 | 15.6 | 7.4 | 3.4 | 564 | 33.7 | 20.4 | 8.3 | 2.5 |

| 2007–2008 | 591 | 30.8 | 17.1 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 268 | 27.0 | 15.6 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 323 | 34.2 | 18.4 | 7.6 | 3.1 |

| 2009–2010 | 647 | 34.3 | 20.0 | 8.7 | 3.0 | 286 | 32.3 | 17.8 | 9.7 | 3.4 | 361 | 36.0 | 22.0 | 7.7 | 2.6 |

| 2011–2012 | 593 | 32.8 | 17.6 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 292 | 32.8 | 17.4 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 301 | 32.8 | 17.9 | 6.7 | 3.2 |

| 2013–2014 | 668 | 36.7 | 21.2 | 12.4 | 5.4 | 340 | 35.6 | 20.8 | 15.1 | 7.5 | 328 | 37.8 | 21.6 | 10.0 | 3.6 |

| 2015–2016 | 583 | 41.5 | 20.5 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 294 | 47.9 | 21.1 | 9.1 | 5.2 | 289 | 34.8 | 19.9 | 9.8 | 3.8 |

| pa | .200 | .845 | .210 | .594 | .032 | .944 | .076 | .349 | .599 | .744 | .945 | .873 | |||

| pb | .001 | .031 | .003 | .002 | <.001 | .035 | .007 | .013 | .410 | .410 | .090 | .017 | |||

P value from an adjusted Wald test comparing the 2013–2014 cycle to the 2015–2016 cycle.

P value from the linear trend across 1999–2016.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Females From 1999 to 2016 by Race

| White | African American | Hispanic | Other, Including Asian American | Asian American | Other Non–Asian American | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 23.1 | 37.8 | 31.7 | 28.5 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 26.5 | 37.0 | 35.4 | 23.7 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 31.9 | 40.7 | 34.7 | 18.4 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 27.4 | 38.7 | 35.6 | 16.0 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 29.2 | 39.1 | 36.2 | 16.9 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 25.6 | 41.0 | 38.7 | 23.7 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 29.2 | 36.1 | 37.5 | — | 13.7 | 37.7 |

| 2013–2014 | 27.5 | 41.1 | 42.6 | — | 16.7 | 39.9 |

| 2015–2016 | 29.5 | 43.7 | 45.5 | — | 22.5 | 38.4 |

| pa | .575 | .601 | .284 | — | .286 | .891 |

| pb | .282 | .211 | <.001 | .487 | .118 | .964 |

| Class I Obesity | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 12.0 | 21.5 | 15.4 | 18.4 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 12.6 | 19.7 | 17.3 | 8.3 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 14.8 | 24.0 | 17.1 | 6.2 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 12.5 | 24.4 | 20.8 | 5.6 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 14.9 | 23.1 | 17.2 | 4.9 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 11.7 | 24.3 | 19.0 | 11.6 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 15.6 | 20.7 | 20.6 | — | 5.6 | 19.7 |

| 2013–2014 | 14.8 | 20.9 | 22.1 | — | 5.0 | 19.4 |

| 2015–2016 | 13.6 | 25.1 | 23.5 | — | 10.1 | 20.9 |

| pa | .690 | .349 | .600 | — | .042 | .820 |

| pb | .382 | .620 | <.001 | .336 | .175 | .866 |

| Class II Obesity | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 3.0 | 7.9 | 3.5 | 4.9 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 1.9 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 4.1 | 10.3 | 5.4 | 0.9 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 6.6 | 1.2 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 3.7 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 0.7 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 4.4 | 9.5 | 5.4 | 1.9 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 4.7 | 10.2 | 7.0 | — | 1.0 | 6.5 |

| 2013–2014 | 6.0 | 8.6 | 8.9 | — | 0.4 | 4.4 |

| 2015–2016 | 3.8 | 9.5 | 6.3 | — | 1.2 | 6.5 |

| pa | .200 | .754 | .142 | — | .489 | .554 |

| pb | .087 | .596 | .037 | .279 | .890 | .945 |

| Class III Obesity | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 1.0 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 0.5 | — | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2013–2014 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 2.0 | — | 0.0 | 2.1 |

| 2015–2016 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 2.6 | — | 0.0 | 1.3 |

| pa | .139 | .808 | .537 | — | — | .650 |

| pb | .003 | .263 | .215 | .155 | — | .311 |

—, not applicable.

P value from an adjusted Wald test comparing the 2013–2014 cycle to the 2015–2016 cycle.

P value from the linear trend across 1999–2016.

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Males From 1999 to 2016 by Race and/or Ethnicity

| White | African American | Hispanic | Other, Including Asian American | Asian American | Other Non–Asian American | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 27.5 | 30.9 | 37.4 | 25.5 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 28.2 | 27.5 | 38.8 | 35.6 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 35.2 | 30.7 | 40.4 | 22.8 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 28.2 | 31.1 | 40.1 | 26.2 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 29.6 | 33.4 | 39.7 | 29.0 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 30.5 | 37.3 | 39.8 | 29.4 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 28.1 | 34.2 | 40.7 | — | 25.1 | 38.7 |

| 2013–2014 | 31.5 | 33.1 | 41.3 | — | 24.6 | 31.3 |

| 2015–2016 | 30.2 | 32.0 | 46.3 | — | 23.9 | 44.6 |

| pa | .642 | .676 | .133 | — | .880 | .113 |

| pb | .714 | .017 | .021 | .935 | .772 | .324 |

| Class I Obesity | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 11.0 | 16.5 | 22.9 | 14.6 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 15.0 | 15.6 | 20.6 | 18.1 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 17.6 | 16.4 | 21.5 | 16.9 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 13.8 | 18.3 | 25.0 | 11.1 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 15.9 | 17.5 | 24.2 | 17.7 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 16.6 | 24.3 | 23.6 | 14.2 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 12.6 | 20.4 | 23.9 | — | 11.5 | 21.6 |

| 2013–2014 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 21.2 | — | 11.3 | 21.0 |

| 2015–2016 | 14.7 | 19.3 | 28.0 | — | 11.2 | 29.7 |

| pa | .544 | .443 | .059 | — | .979 | .439 |

| pb | .472 | .041 | .208 | .756 | .933 | .400 |

| Class II Obesity | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 2.8 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 5.4 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 8.7 | 4.7 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 4.6 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 4.9 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 3.5 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 3.6 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 4.2 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 5.3 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 4.9 | 12.0 | 8.1 | 4.2 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 3.2 | 10.3 | 8.3 | — | 2.8 | 11.6 |

| 2013–2014 | 4.7 | 6.2 | 7.8 | — | 2.1 | 8.8 |

| 2015–2016 | 4.0 | 8.6 | 11.9 | — | 1.5 | 8.8 |

| pa | .578 | .278 | .062 | — | .681 | .998 |

| pb | .927 | .046 | .023 | .821 | .316 | .773 |

| Class III Obesity | ||||||

| 1999–2000 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | — | — |

| 2001–2002 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | — | — |

| 2003–2004 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 | — | — |

| 2005–2006 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2007–2008 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 2.0 | — | — |

| 2009–2010 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 1.9 | 0.0 | — | — |

| 2011–2012 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 | — | 0.8 | 7.1 |

| 2013–2014 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 2.1 | — | 0.9 | 6.2 |

| 2015–2016 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 4.0 | — | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| pa | .329 | .390 | .138 | — | .330 | .149 |

| pb | .399 | .107 | .069 | .613 | .346 | .242 |

—, not applicable.

P value from an adjusted Wald test comparing the 2013–2014 cycle to the 2015–2016 cycle.

P value from the linear trend across 1999–2016.

Differences From the Last Cycle

There are few differences in the prevalence of overweight and all classes of obesity since the last NHANES cycle, 2013–2014 and 2016–2016. One exception is a sharp increase in the prevalence of class I obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds, particularly in young males. Another notable increase is for overweight, from 36% to 48%, in among older adolescent females. There were no other significant changes from the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 cycles for any of the race and/or sex subgroups in any of the obesity categories.

DISCUSSION

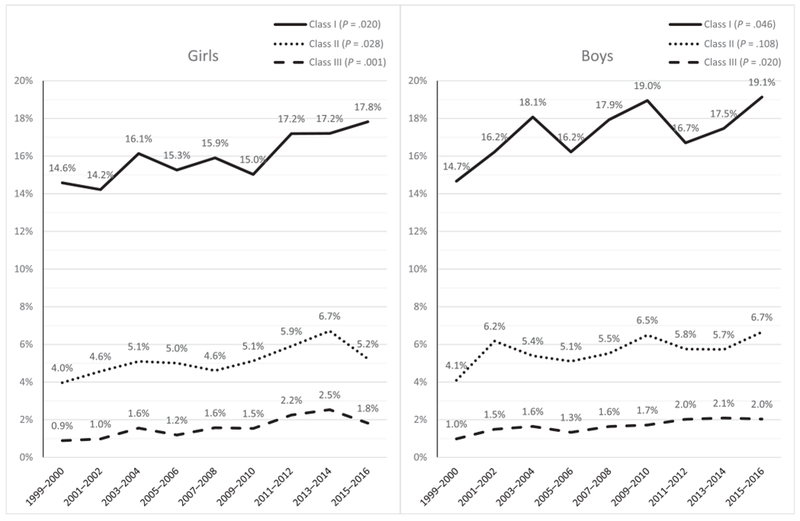

Despite reports that obesity in children and adolescents in the United States has stabilized in recent years,1 our more nuanced view highlights the continued upward trend for this nationally representative sample (Fig 1). Significant increases in obesity and severe obesity in children aged 2 to 5 years and adolescent females aged 16 to 19 years from 2015 to 2016, compared with previous years, show that obesity is increasing in these subgroups. Whether this year-over-year change represents a trend remains to be seen because shifts per cycle can be large. We recommend that readers consider both the long-term trends as well as changes over 2-year cycles when considering the effects in specific populations.

FIGURE 1.

The prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among US children 2 to 19 years of age from 1999 to 2016.

The prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States remains high, with ~1 in 5 children having obesity. By applying updated obesity classifications16 to data starting in the 1999–2000 cycle of the NHANES, there continue to be increases in most categories of obesity across all age groups. By age, adolescents have had a significantly increased prevalence across all obesity categories since the 1999–2000 cycle. Substantial racial-ethnic differences remain, with African Americans and Hispanics having a higher prevalence across nearly all classes of obesity and all years between 1999 and 2016. Notably, Asian Americans have a much lower prevalence of obesity in all age and sex categories. There were few differences in obesity prevalence from the previous cycle (2013–2014), with the exception of Hispanic males, who saw significant increases, and boys ages 2 to 5 years, who have had a 40% increase in prevalence since 2011.

Despite intense clinical and public health focus on obesity and weight-related behaviors during the past decade, obesity prevalence remains high, with scant evidence that these efforts are counteracting the personal and environmental forces that contribute to excess weight gain in children, at least on a national scope. These findings are disappointing in light of reported decreases in obesity prevalence in younger children,2,4,17–21 which was the only age group as a whole to see a significant increase in prevalence since the 2013–2014 NHANES cycle. Most disconcerting are the substantial disparities in obesity by race and ethnicity; statistical and clinical differences in prevalence between Hispanics and all other races are astounding, with nearly half of all Hispanic youth having overweight or obesity. Building on our previous work,5,6,12 we have been able to document the steadily rising levels of severe obesity, modeled on adult criteria of class I, II, and III obesity, with the rise of children with severe obesity having been the most significant.

Public health efforts to address obesity in children have been extensive, from Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move campaign to the American Academy of Pediatrics establishing a Section on Obesity in 2013 that is distinct from other groups in the academy as well as countless efforts led by states, hospitals, and communities. Despite these efforts, which may have had greater impact in defined populations, more resources are clearly necessary. The obesity epidemic is becoming endemic, and this decline in Americans’ health is occurring without impactful policy at the national level. Evidence-based efforts focused on policy, family-based change, and health improvement (versus weight loss alone) may take another decade to see positive results; effective prevention and treatment interventions remain undeveloped or have not been effectively disseminated, and more insight is needed into the moderators and mediators of excessive weight gain. Additionally, evidence that behaviors in high-risk groups start at a young age suggests that efforts need to focus early in children’s lives.22

There are few long-term studies of obesity development or treatment outcomes because this work is occurring in a Biggest Loser environment, with the focus being on short-term changes in weight that we are only beginning to see as an erroneous pursuit in adult populations.23 These efforts are hampered by declining research dollars, limited or nonexistent reimbursement for prevention and treatment, and difficulties in changing local and national policies that impact environmental health. Finally, there is some evidence of an association between poverty and obesity,24 undoubtedly influencing the health of children nationwide. Activities with the aim of decreasing the prevalence of childhood obesity should not cease but redouble as an effort to improve the health of children and families and stem the rising costs of health care in the United States.

There are several important limitations to note. First, the NHANES data are repeated cross-sections and do not allow for the examination of within-child changes over time. However, this approach allows for a richer picture of obesity prevalence across the United States. A second limitation is that the sample sizes prevent detailed subgroup analyses. We present prevalence rates by age, sex, and race, but caution should be used when interpreting these results. Readers should consider the body of evidence rather than focusing on individual tests of significance. Finally, the inclusion of Asian Americans in this report highlights questions about the reference ranges that define obesity. The current reference charts were developed by using data from a more homogenous group than what is seen in the United States today. It is not clear if the definitions of obesity represent similar levels of adiposity across racial and ethnic groups or if they confer similar levels of health risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Nationally representative data provided by the NHANES demonstrates clearly that childhood obesity continues to be a significant concern for the United States. The past 18 years have seen increases in the levels of severe obesity in all ages and populations despite increased attention and efforts across numerous domains of public health and individual care. Groups that are historically disenfranchised are affected the most by this epidemic, predicting increased morbidity across a lifetime. Previously reported improvements seen in younger children were either an anomaly or transient because national data presented here demonstrate a sharp increase from the last cycle. Present efforts must continue, as must innovation, research, and most importantly at this juncture, collaboration among clinicians, public health leaders, hospitals, and all levels of government.

Supplementary Material

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

The US prevalence of child and adolescent obesity has been increasing for 4 decades. Some reports reveal stabilization across the population and decreases among young children aged 2 to 5 years, although severe obesity has increased, with adverse health effects.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

We detail the prevalence of obesity and severe obesity by age and race and/or ethnicity, including Asian American youth, in a nationally representative sample. Despite significant public health initiatives, obesity and severe obesity continue to increase, with a sharp increase being noted in preschool-aged children.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: Dr Skinner, Ms. Ravanbakht, and Dr Armstrong are supported by an American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network Award, 17SFRN33670990.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CDC:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

confidence interval

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2017-4078.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311 (8):806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(219):1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan L, Freedman DS, Sharma AJ, et al. Trends in obesity among participants aged 2-4 years in the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children - United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(45):1256–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Skelton JA. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999-2014. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(5):1116–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner AC, Skelton JA. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999-2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):561–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow SE; Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(suppl 4):S164–S192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DS, Butte NF, Taveras EM, et al. BMI z-scores are a poor indicator of adiposity among 2- to 19-year-olds with very high BMIs, NHANES 1999-2000 to 2013-2014. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(4):739–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1314–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanderwall C, Randall Clark R, Eickhoff J, Carrel AL. BMI is a poor predictor of adiposity in young overweight and obese children. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman DS, Berenson GS. Tracking of BMI z scores for severe obesity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Moss LA, Skelton JA. Cardiometabolic risks and severity of obesity in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1307–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(288):1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002;(246):1–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Skelton JA. Cardiometabolic risks and obesity in the young. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(6):592–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly AS, Barlow SE, Rao G, et al. ; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Severe obesity in children and adolescents: identification, associated health risks, and treatment approaches: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(15):1689–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May AL, Pan L, Sherry B, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: obesity among low-income, preschool-aged children--United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(31):629–634 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan L, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Dalenius K, Grummer-Strawn LM. Trends in the prevalence of extreme obesity among US preschool-aged children living in low-income families, 1998–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2563–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen X, Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Sherry B, Kleinman K, Taveras EM. Decreasing prevalence of obesity among young children in Massachusetts from 2004 to 2008. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):823–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robbins JM, Mallya G, Wagner A, Buehler JW. Prevalence, disparities, and trends in obesity and severe obesity among students in the school district of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2006-2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day SE, Konty KJ, Leventer-Roberts M, Nonas C, Harris TG. Severe obesity among children in New York City public elementary and middle schools, school years 2006-07 through 2010-11. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrin EM, Rothman RL, Sanders LM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences associated with feeding- and activity-related behaviors in infants. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/4/e857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “the biggest loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(8):1612–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H, Andrew M, Gebremariam A, Lumeng JC, Lee JM. Longitudinal associations between poverty and obesity from birth through adolescence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):e70–e76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.