Abstract

This study seeks to characterize how non-directed living kidney donors use media and informational resources over the course of their kidney donation journey. We conducted semi-structured interviews with non-directed donors (NDDs) who initiated kidney transplant chains. Interview transcripts were reviewed and references to media or informational resources were classified by type and pattern of use. More than half (57%) of NDDs reported that an identifiable media or informational resource resulted in their initial interest in donation. Two-thirds (67%) of NDDs cited the influence of stories and personal narratives on their decision to donate. After transplant, media and informational resources were used to promote organ donation, connect with other donors or recipients, and reflect on donation. From the study’s findings, we conclude that media and informational resources play an important role in the process of donation for NDDs, including inspiring interest in donation through personal narratives. Media sources provide emotionally and intellectually compelling discussions that motivate potential donors. The results of this study may facilitate the development of more targeted outreach to potential donors through use of personal narratives in articles and television programming about donation.

Keywords: Altruism, kidney donation, kidney transplant chains, non-directed donors, transplant, media, social media

Introduction

At the end of 2015, there were >100,000 individuals awaiting kidney transplant in the United States (U.S.). In that same year, 15,000 kidney transplantations were performed—10,000 deceased donor and 5,000 living donor transplants (OPTN data, Jan. 2016). A shortage of willing donors, who are matched to their recipients, limits the number of transplants that can be completed.

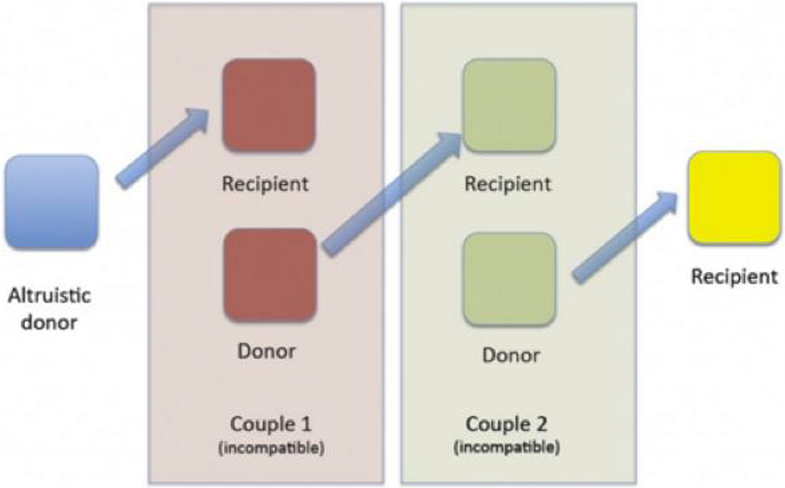

One strategy for increasing transplantation involves efficient use of living donors’ contributions via kidney transplant chains. Most living donor kidney transplants are “directed”, where the kidney donor has a direct relationship with the recipient. A small number of living donor kidney transplants are from non-directed donors (NDDs), who donate their kidneys to strangers. These donors are also known as altruistic, unspecified, anonymous, and “Good Samaritan” donors (Maple et al., 2014). NDDs are a valuable asset to the transplant community because there is flexibility in the use of their contributions. Organs from NDD’s can be donated to a single, matched individual on a waiting list, or they can catalyze kidney transplant chains, which enable several successive transplants (Figure 1) (Melcher et al., 2013). A recent nationwide study showed that 77 NDDs enabled 373 transplantations over a 46-month period, exemplifying the capacity of NDDs for increasing the volume of living-donor transplantation (Melcher et al., 2013).

Figure 1:

Initiation of a Kidney Chain by a Non-Directed (Altruistic) Kidney Donor. Adapted from “Give a Kidney - One’s Enough” A registered charity in England and Wales. Copyright 2015

A second strategy for increasing transplantation involves expanding the donor pool through improved outreach to potential donors. Prior attempts to promote organ donation used multiple modes of media including flyers, pamphlets, mailings, television programming, videos, books, websites, and social media (Alvaro, Jones, & Robles, 2006; Morgan, 2009; Wakefield, Loken, & Hornik, 2010). In 2012, Facebook successfully initiated one of the largest outreach campaigns to register potential deceased organ donors (Cameron et al., 2013). In cooperation with the transplant team at Johns Hopkins, the Living Legacy Foundation of Baltimore and Donate Life America, Facebook offered users the opportunity to list themselves as organ donors in their profiles. When Facebook users designated themselves as donors, they were prompted to sign up as organ donors with their state registry. On the first day of the campaign, 13,054 new organ donors registered, a 21.1-fold increase from baseline (Cameron et al., 2013). Similarly, YouTube has been used to promote organ donation and smartphone apps have been developed to serve as electronic organ-donor cards and to access national transplant registries (Connor, Brady, & Marson, 2014; Tian, 2010; VanderKnyff, Friedman, & Tanner, 2014). A 2014 study showed that a two-year media campaign via television and radio could significantly increase the intent to become an organ donor among Hispanic Americans (Salim et al., 2014). Even direct mail campaigns have been shown to increase registration of organ donors (Quick, LaVoie, Morgan, & Bosch, 2015).

While these direct media campaigns have successfully recruited organ donors, the general media has a more complex effect on societal perceptions of organ donation. In attempt to understand this complex effect on public opinion, several studies have sought to characterize the content of media that covers organ donation. Many forms of general media present only the most interesting (and unusual) stories about organ donation. For example, Harrison et al. found that while organ donation appears with high frequency on television news, a large amount of airtime is dedicated to a small number of stories about organ donation (Harrison, Morgan, & Chewning, 2008). Dramatic stories are overrepresented in this form of media (Harrison, Morgan, & Chewning, 2008). Additionally, facts about donation are occasionally distorted during discussions among news anchors (Harrison, Morgan, & Chewning, 2008). Similarly, while organ donation is commonly portrayed in entertainment television (153 episodes featured plotlines with organ donation), these episodes often present uncommon and unlikely scenarios such as transplantation of illegally acquired organs or organs harvested accidentally from patients without brain death (Harrison, Morgan, & Chewning, 2008). Exaggerated, negative, and suspicious representations of organ donation in television media has been documented and discussed in several other studies (Morgan, et al., 2005; Morgan, Harrison, Chewning, Davis, & Dicorcia, 2007; Morgan, Harrison, Afifi, Long, & Stephenson, 2008). Not all portrayals of organ donation in television media are negative. Many television programs (both news and entertainment) emphasize positive elements of donation, such as the altruism of donors (Harrison, Morgan, & Chewning, 2008; Morgan, Harrison, Chewning, Davis, & Dicorcia, 2007). However, suspicious representations of organ donation seem to be commonplace in television media. Print media tends to present organ donation in a positive light, though also with a focus on dramatic, unusual stories. A study of the representation of organ donation in newspapers found that most articles discussed the health implications of donation and the shortage of organs available for transplant (Feeley & Vincent, 2007). Of these articles, 57% portrayed organ donation in a positive light and only 14% were negative (e.g. medical errors or complications).

What is the influence of this media coverage of organ donation on individual and societal perceptions of donation? Mass media is frequently cited as a source of information about organ donation, and several studies have sought to identify which media sources increase the public knowledge (Feeley & Vincent, 2007; Feeley & Servoss, 2005). For example, Rubens et al. found that of 742 students, most knew about organ donation from TV, newspaper and magazines (Rubens et al., 1998). Morgan et al. found that among a population of African American subjects, the most commonly cited sources of information regarding organ donation were family members (42%), television (38%), newspapers (31%), magazines (26%), and radio (18%) (Morgan, et al., 2003). How opinions are shaped by these sources of information is difficult to assess. However, literature supports the notion that societal opinions about organ donation are indeed shaped by media content, in both positive and negative ways. Morgan et al. found that in family discussions about organ donation, negative opinions about organ donation “were almost always justified with information, stories, or images from the mass media” (Morgan et al., 2005). Interestingly, this is in contrast to positive opinion about donation, which were more likely to be “attributed to personal values and beliefs” (Morgan et al., 2005). Negative opinions about donation may result from a focus on certain problems in entertainment television and the news. For example, participants had a “belief in a black market for transplants [that] is widespread among Americans” and a fear that “doctors manipulate the organ allocation system”—two scenarios that receive significant media attention despite low frequency in the U.S. From this and other studies, however, it is clear that media may significantly shape individual and societal opinions—and likely actions—regarding organ donation. Quick and colleagues have documented that greater coverage of organ donation on television news programs (on NBC, ABC, and CBS) positively correlates with the number of organs transplanted. Though cause and effect are impossible to infer from this study, it is reasonable to suspect that greater awareness of organ donation leads to higher donation rates (Quick et al., 2007).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify and characterize media utilization by NDDs, specifically, at all stages of their kidney donation process.

While several studies have sought to analyze the motivations of kidney donors, especially NDDs, few have characterized the way media played a role in their decision to donate (Jacobs, Roman, Garvey, Kahn, & Matas, 2004; Maple et al., 2014; Matas, Garvey, Jacobs, & Kahn, 2000). A University of Minnesota study of NDDs recognized that at least 65% of individuals who contacted their center with an interest in non-directed donation learned about kidney donation from the media or the Internet (Jacobs et al., 2004). Similarly, a cross-sectional study of the motivations, outcomes and characteristics of NDDs showed that 58.2% of donors learned about altruistic kidney donation through the media (Maple et al., 2014). This statistic highlights the significant role of the media in NDD transplantation and therefore the potential utility of studying this relationship.

In this study, we publish data from semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 30 non-directed kidney donors recruited from three kidney donation agencies. The purpose of this study is to a) characterize the forms of media and informational resources used by NDDs during their donation process, b) characterize how NDDs used resources during their donation process, and c) identify how these resources influenced NDDs in their decision to donate.

Methods

Study design

This is a qualitative, content analysis study that employed grounded-theory techniques to analyze interviews with participating NDDs and describe their use of media and informational resources. The study is ancillary to a larger study, Understanding Donor Choice (UDC), which aims to describe the characteristics and decisional processes of NDDs. The COREQ 32-item criteria checklist for comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies was adopted as the primary guide for the procedures and report process of this study (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). An Institutional Review Board approved all study activities.

The multidisciplinary research team included individuals with experience in kidney transplantation, urology, nursing, and health services research. Team members had extensive experience conducting qualitative and quantitative research studies with clinical populations. All authors had multiple roles in the development, implementation, and evaluation of this study. Among the various roles, there were two interviewers and four coder analysts who were trained and overseen by an experienced qualitative researcher.

Patient Selection

Thirty-one NDDs were enrolled in the study. Participants were recruited from three sources: 1) The National Kidney Registry, 2) Living Donation California, and 3) the UCLA Kidney Exchange Transplant Program. Sample size was determined according to grounded theory guidelines, also applicable to content analysis, which requires 20–30 in-depth interviews in order to achieve category saturation (Charmaz, 2014; Thorne, 2016). Seventy-six NDDs were contacted and invited to participate in the UDC study. Potential participants were asked to directly contact the study coordinator if they wished to participate in the study. Of the 46 individuals who responded to the invitation: 31 were enrolled, 9 were lost to follow-up, 5 were ineligible, and 1 withdrew from the study. One NDD interview was excluded from the analysis due to a failed recording, thus there were a total of 30 NDDs included in the current study. The study coordinator, interviewers, and qualitative/quantitative analysts had no prior communications or relationships with the study sample.

Participants were required to have donated a kidney as an NDD within the U.S., be ≥ 21 years of age or older, and able to read and speak English. Individuals were excluded from our analysis if they had not completed a non-directed donation.

Data

Upon receiving oral consent from the participants, interview dates were scheduled. All interviews were conducted via telephone from a private office. The interviews were audio recorded and ranged from 45–90 minutes in duration. Qualitative data was collected by interviewers utilizing a semi-structured interview guideline. Quantitative data was collected by survey following the interview. All participants received a $15 gift card for their participation. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using Atlas.ti. Survey data were entered and imported into SAS (Durham, NC).

Analysis

Analysts coded interview data by reading each transcript in its entirety and identifying references to media and informational resources. Each transcript was read by each of the four coders and analyzed line-by-line to code references to media by media type, time of media exposure (before or after transplant), and the role that media played for the interview subject. Codes for media type and media role were refined in weekly meetings, with comparison of each coder’s results, until consensus was reached on the set of codes to be used. Rigor in the qualitative analysis was strengthened through maintaining memos on the discussion of coding discrepancies.

Eight categories were developed for “type of media/informational resources”: internet sources, articles, television programming, social media, events/speakers, video content, print content (mailings/flyers/posters) and other. For references that may have been categorized by more than one media/resource type (e.g. a newspaper article accessed via the web), the reference was assigned to what was deemed its primary category. For the purposes of this study, a newspaper or magazine article accessed via the web was categorized as an article. YouTube videos were categorized as video content and not as internet sources or social media. Explicit references to Facebook, Instagram or Twitter were categorized as social media, as were any references to NDDs finding “posts” by acquaintances online. The category of internet sources included references to searching online or to informational websites, such as the National Kidney Registry’s website. For a detailed description of how these categories were organized see Appendix A.

Seven major themes were identified by coders to describe the role of media and informational resources (e.g. the way these resources were used) during non-directed donation that are elaborated in the results below. During the content analysis process, senior authors approved final decisions, processes, and interpretation of results.

A descriptive analysis of demographic variables was completed. For continuous variables such as age, we calculated mean and standard deviation. For categorical variables, we calculated frequencies.

Results

Participant demographics

Several demographic trends were demonstrated within the study group. The majority of NDDs were white individuals (97%) with college degrees (87%). Most were married (77%) and had annual household incomes >$100,000 (64%) (Table 1). These NDDs had a tendency to engage in other altruistic activities: 77% of participants were engaged in volunteer activities at the time of interview.

Table 1:

Demographic information for participating NDDs

| Characteristic | n = 30 (%) | Mean (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Database | -- | |

| Living Donor California | 6 (20%) | |

| National Kidney Registry | 21 (70%) | |

| UCLA | 3 (10%) | |

| Sex | -- | |

| Male | 13 (43%) | |

| Female | 17 (57%) | |

| Age at interview | 47.5 (27–63) | |

| ≤50 | 16 (53%) | |

| >50 | 14 (47%) | |

| Race | -- | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (3%) | |

| White | 29 (97%) | |

| Education level | -- | |

| No college | 4 (13%) | |

| College degree | 26 (87%) | |

| Income level† | -- | |

| <$25,000 | 1 (4%) | |

| $25–50,000 | 3 (11%) | |

| $50–100,000 | 6 (21%) | |

| >$100,000 | 18 (64%) | |

| Insurance type | -- | |

| Private | 22 (73%) | |

| Medicare | 0 (0%) | |

| Medicaid | 2 (7%) | |

| Military insurance | 1 (3%) | |

| Other government plan | 2 (7%) | |

| Other insurance plan | 1 (3%) | |

| Marital status | -- | |

| Single | 3 (10%) | |

| Married | 23 (77%) | |

| Divorced | 4 (13%) | |

| Widow | 0 (0%) | |

| Blood donors† | 21 (75%) | -- |

| Registered organ donors † | 28 (100%) | -- |

| Registered bone marrow donors † | 21 (75%) | -- |

| Donors of other organs † | 2 (7%) | -- |

| Current volunteer work | 24 (77%) | -- |

| Past volunteer work | 27 (96%) | -- |

Data missing for two participants (percentage calculated with 28 total participants)

Types of informational resources and media used by NDDs

Ninety-seven percent of NDDs made reference to the role that media or promotional events played in their kidney donation process. A range of resource types were discussed, including internet content, newspaper/magazine articles (often published online), social media, and television programming. The various types of informational resources used by NDDs are listed, by frequency of use, in Table 2.

Table 2:

Informational resources used by NDDs

| Resource type | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Internet content | 24 (80%) |

| Article (Newspaper/Magazine) | 14 (47%) |

| Television content | 9 (30%) |

| Social Media | 9 (30%) |

| Events/Speakers | 6 (20%) |

| Video content | 9 (30%) |

| Print content (Mailing/Flyer/Poster) | 6 (20%) |

| Other | 3 (10%) |

Role of media and informational resources in the period prior to transplantation

Of the 30 donors, 28 (93%) made direct reference to using media to learn more about the process of donation and 17 (57%) indicated that they were first inspired toward non-directed kidney donation through media (Table 3). Inspiration to donate was most commonly stimulated by newspapers/magazine articles (20%) or television programming (17%), but also by the Internet (7%), print content (7%), and social media (3%). For the majority of study participants, media content led them to the idea of kidney donation. They were not actively seeking opportunities for altruism. The small minority who were passively interested in altruistic opportunities discovered media sources about non-directed donation that guided them.

Table 3:

Role of media for NDDs n (%)

| Pre-transplant period | |

| Media provided information about donation | 28 (93%) |

| Media created impulse to donate | 17 (57%) |

| Post-transplant period | |

| Promote organ donation and spread awareness | 12 (40%) |

| Connect with other donors | 4 (13%) |

| Self-reflection | 3 (10%) |

| Contact organ recipient or obtain information about recipient | 3 (10%) |

| Other (e.g. religious expression, stay-up-to-date with transplant news, unknown, etc.) |

9 (31%) |

Media as inspiration to become a non-directed kidney donor.

Many participants described first learning about living or non-directed kidney donation through the media (Table 4). Indeed, many participants answered the question “How did you decide to donate your kidney?” with a description of media sources that influenced them. Many of these participants explicitly credited these sources with providing the inspiration for their decision to become an NDD.

Table 4:

Media as inspiration to become a non-directed kidney donor

| …I somehow came across a link to the article that was in the New York Times about the long donation chain and I started reading that article and was immediately struck by it… halfway through the 1st page and I knew that I was going to do it |

Donor 167 |

| I learned that I could in 2010 from a news article that I sort of forgotten where I found it. But I thought that is something I can do… |

Donor 199 |

| The first thing that I read that illuminated the possibility that someone could donate their kidney… was an article by Larissa MacFarquhar called ‘The Kindest Cut’… that sort of planted the seed. I think the second time that I thought seriously about it was after the New York Times A1 feature where they talked about the NKR chain that had 60 people in it… |

Donor 177 |

| [Katie Couric] did a story on kidney chains. And it was I think connecting 20 different people across the country. And it all started with a carpenter. And this average Joe kind of carpenter. And I thought that the whole story was so amazing because I didn’t know you could do that. I didn’t know there were people who could donate to folks they weren’t related to. I didn’t know you could do that when you were alive. ... it was just a matter of a week maybe that I had emailed or signed up on the National Kidney Registry site as a courier of my interest… |

Donor 151 |

| I had seen an update from a friend online that he had donated his kidney to a friend. I actually thought he had donated it to a stranger at the time... But I just always had thought what a neat thing. And it sort of percolated in the back of my mind that might be something I would like to do… |

Donor 156 |

Interestingly, several sources were cited more frequently than others as the inspiration to become an NDD. Four donors cited a New York Times article entitled,”60 Lives, 30 Kidneys, All Linked” (Sack, n.d.). Two donors cited a Katie Couric evening news story about a kidney transplant chain (aired in November 2010). Both of these sources reached a broad audience and provided first person narratives from kidney donors and recipients.

Indeed, first-person narratives and donor/recipient stories were common to many media sources that inspired NDDs to donate. For example, NDDs in this study made reference a New Yorker article entitled “The Kindest Cut” (MacFarquhar, 2009), a New York Times Magazine article, several local newspaper articles (e.g. the Star Ledger), and several speaking engagements all of which contained stories about donation providing inspiration to them to become NDDs. Sixty-seven percent of study participants cited media sources with donation stories as an influence in their decision to become an NDD.

Role of media and informational resources in the period following transplantation

When discussing the role of media post-transplantation, NDDs focused less on media as a source of inspiration or information and more on the use of media to promote organ donation, to connect with other donors, and as a mode for self-reflection (Table 3). The forms of media used by NDDs in the post-transplant period differed from forms used in the pre-transplant period. For example, video content played a more important role for NDDs after undergoing transplantation.

Of the 30 donors, 19 (63%) made reference to their use of media or their participation in promotional events after completing their kidney donations. Promotion of organ donation (and of non-directed donation, specifically) was the most common reason NDDs cited for using the media post-transplantation (Table 2). The most common mediums discussed by these donors were internet sources (30%), articles (23%), events and speakers (20%), video content (17%), television content (10%), and print content (10%).

Media as a means to promote donation.

Forty-one percent of participants promoted organ donation post-transplant (Table 5). This number reflects all forms of organ donation, though most NDDs specifically promoted non-directed kidney donation by writing articles for newspapers and magazines and accepting speaking engagements with organizations such as Donate Life California (Donor 14). One participant (Donor 22) even enlisted a documentary filmmaker to make a documentary about the donation journey.

Table 5:

Media as a means to promote donation

| … I’ve become involved with a donate life California. I sometimes speak. I’ve spoken at Berkeley a couple times to some groups of about 200 kinds; young people. I have spoken in the service organizations around here. I’ve also a donate life ambassador or something. So I’ll sometimes talk to the DMV; they’re the ones that sign people up to be organ donors. And sometimes I have been to the local high school with some other people involved; and we’ve spoken to classes about our experiences. |

Donor 14 |

| …I said, I’m going to do this anyway… somebody needs to make a film, because people need to know about this and be able to do this. You can reach people with newspaper articles and a web site, but film is just really provocative. It really gets people thinking. |

Donor 22 |

| So the funny thing is after I donated I wrote about it. It got published as an opinion piece in a newspaper … the whole chain donation resonated for me and sort of maximized the benefit of what you can do for multiple people. That’s probably the basic structure of how I’d talk to people about it. |

Donor 177 |

Only a few NNDs discussed the specific arguments they used to promote non-directed donation. One NDD (Donor 177) wrote an opinion piece about non-directed donation for a newspaper that discussed the significance of numbers and statistics in advocacy. When writing about non-directed donation, this NDD highlighted the number of people in need of kidneys and the number of people that can be helped by a single NDD through chain donations.

Media as a means to connect with other donors.

Several donors highlighted the role that media played after donation in helping them connect with other donors (Table 6). The Internet provided a forum for NDDs to connect with one another, to share ideas and experiences. For example, one NDD (Donor 194) mentioned how the Internet and social media provided a forum for discussing the variability in follow-up care that NDDs experienced at different transplant centers. The donor used social media to advise potential donors on how to find mentors to guide them. Others discussed how they connected with prospective NDDs to answer questions about donation. One participant (Donor 156) saw a poster about a state’s transplant foundation and joined the organization’s mentoring program.

Table 6:

Media as a means to connect with other donors

| You kind of become a part of a little - even though it’s part of the Internet; kind of a part of a group that you didn’t even know existed with the organ donors and so forth. It’s almost like a little fraternity or sorority or whatever you want to call it. |

Donor 14 |

| One of the sort of lingering issues in my community – by that I mean the donor community is the follow-up care. It’s very, very inconsistent across the board and I hear with other conversations I do have via the Internet, phone calls, and social media |

Donor 194 |

| Online there are groups… I joined some groups having to do with kidney donation on YouTube and on Facebook…. and on LinkedIn. |

Donor 181 |

Media as a means of self-reflection.

Many donors used media not to reach or inspire others, but rather to focus on processing their experiences as donors (Table 7). Though these donors didn’t describe their use of media as “self-reflection”, the context and description of their media use indicated a process of reflection. For example, one donor blogged about the experience (Donor 181) to create something “meaningful” and “share personal things”. Another donor (Donor 27) described participating in an event, the Transplant Games, to acknowledge the 10-year anniversary of their donation. The donor wrote “I was trying to figure out some way to acknowledge that it is 10 years because I kind of hid behind this wall of anonymity for 10 years…I was trying to figure a way to acknowledge the anniversary in a subtle way.” Another donor (Donor 167) described posting on social media to acknowledge the one-year anniversary of their transplant. These individuals used media and other resources as a tool not only to reach other people, but also to acknowledge meaningful dates (anniversaries) or to reflect on the uniqueness of their journey (“to share personal things”). These examples illustrate how some NDDs sought to express or acknowledge their own experiences through media use, which can be described as self-reflection.

Table 7:

Media as a means of self-reflection

| And my 1-year anniversary I posed about it on Facebook saying I was 1 year post-donation and got a lot of feedback from people – from friends saying that they consider me to be a hero and everybody re-expressing their amazement |

Donor 167 |

Discussion

Analysis of Results

This study has significant implications for recruitment of potential NDDs and living kidney donors. As most NDDs highlighted the impact of media in inspiring them to become donors, the role of media in promoting donation cannot be underestimated. This study underscores what types of media may most effectively reach potential donors and prompt them to follow through with donating a kidney. Newspaper and magazine articles, as well as TV programming, were the two most commonly cited forms of media to spark interest in donation among NDDs. In this study, NDDs highlighted the information articles and television provided, including explanations of chain donation and the ethical issues of living donation. Articles and TV programming may provide more information about donation than other forms of media.

The results of this study are particularly interesting in the context of current literature on media and organ donation. Most of the subjects of this study were stimulated to donate by information they learned from the general media, not from organized pro-donation campaigns. As highlighted in the introduction, general media coverage of organ donation tends to highlight more extreme – and often negative – stories related to organ donation (Harrison, Morgan, & Chewning, 2008; Morgan, Harrison, Chewning, Davis, & Dicorcia, 2007). This is especially true for television media, both news and entertainment. Indeed, the literature has even suggested that many individuals cite these negative portrayals of organ donation as reasons for not registering as organ donors (Morgan et al., 2005). As such, it is important to note that positive stories about donation on TV played a significant role in encouraging non-directed donation. The influence of print media on non-directed donors is less surprising as print media has been documented to contain more positive donation-related content (Feeley & Vincent, 2007).

It should be noted that the theoretical ability of media to sway public opinion is itself a complex topic. Some social theories, such as agenda setting theory, suggest that media does not truly shape societal opinions, but merely directs society to think about particular topics (Feeley & Vincent, 2007; Kosicki, 1993). Media may set “the public’s agenda for a topic… force attention to certain issues and influence the salience or importance of the topic in the opinions and attitudes of the general public” (Feeley & Vincent, 2007; Kosicki, 1993). Other theories, such as social representation theory, contend that “discursive practices are paramount in the construction of [a] social world” (Moloney & Walker, 2000). In other words, as regards media and organ donation, the way we discuss and portray donation – even via the media – may shape societal opinions on the topic. This tenet is more likely to be true “when individuals lack personal experience with a relatively unknown phenomenon” – a condition that holds true for organ donation (Harrison, Chewning, Davis, & Dicorcia, 2007). The results of this study suggest that while it may be difficult to assess how media shapes individual opinions about donation, media appears to have the power to encourage people towards taking action.

Articles and television programming had the most significant impact on NDDs in this study. These sources often contained specific stories about NDDs and transplant recipients. This result is consistent with current literature on the effectiveness of narrative for motivating living organ donation (Davis, 2011). The emotional appeal of narrative has documented efficacy in motivating individuals toward altruistic behavior. Studts et al. compared two strategies for recruiting medical students into the National Marrow Donor Program (Studts, Ruberg, McGuffin, & Roetzer, 2010). The first strategy used emotional appeal (e.g. a story of marrow donation) and the second used rational appeal (e.g. statistical arguments). Emotional appeal was significantly more effective than rational appeal in recruiting students to become registered marrow donors (85% vs. 49%). Similarly, visual media that uses narrative engenders sympathy or empathy, and thereby encourages a viewer’s involvement in organ donation (Bae, 2008). Articles and TV programming with stories about non-directed donation may make such emotional appeals to potential NDDs. Furthermore, current literature suggests that culturally tailored sources of information are more effective at promoting living donor kidney transplant (Waterman, Robbins, & Peipert, 2016). It can be theorized that articles and television programming contain a wider array of patient stories and may therefore stimulate an interest in donation among a wide range of individuals.

Interestingly, only one donor cited social media exposures as a source of inspiration for becoming a donor. In light of the success that Facebook achieved with their organ donor registration campaign in 2012, this may be surprising. The age and computer literacy of NDD’s does not explain this finding. The average age of NDDs at the time of this study was 47-years old (range of 27–62), while the Pew Research Center estimates that in 2016, 64% of individuals ages 50–64 and 80% of individuals ages 30–49 used at least one social media site (2017). Furthermore, the vast majority of the individuals in this study are college graduates who used the Internet to research information about donation. This makes it unlikely that the study population had a low level of computer literacy. The limited success of social media in promoting non-directed donation might be explained by other considerations. For example, to our knowledge, no large-scale, dedicated social media campaign has been carried out for non-directed donation. This is one simple explanation for social media’s ineffectiveness in promoting non-directed donation. Alternatively, there may be a fundamental difference in the type of campaign that successfully recruits deceased organ donors and the type of campaign that successfully recruits living donors. Living donors make active and conscious sacrifices. Solicitation of this form of goodwill may necessitate more in-depth advocacy. A Facebook registration campaign may never be as effective as a detailed, personal magazine article to inspire potential NDDs.

In addition to providing information about effective recruitment of NDDs, the current study highlights the resources that NDDs found most helpful during their donation. Online resources played the most significant role in providing NDDs with information and support during transplant. Though this is a wide-reaching category, it reflects the language used by participants who discussed finding information “online.” One specific website cited by many NDDs is the National Kidney Registry website. Further studies would be necessary to identify exactly what types of web resources were most useful to donors (e.g., webinars, info graphics, on-line chats). Several donors indicated that the same online resources could be used to better connect potential donors with veteran NDDs who would serve as mentors. Many study participants found that connecting with prior NDDs was helpful during their donation process.

It should be noted that the vast majority of subjects in this study were white (97%), college educated (87%), and of high socioeconomic status (67% with income >$100,000). There are several explanations for this trend. Current literature suggests that higher level of education is associated with greater exposure to all forms of pro-donation sources (direct campaigns, press, radio, and information from health professionals) (Conesa et al., 2004). It is also possible that high socioeconomic status facilitates the practical needs of altruistic donation by allowing, for example, unpaid time off from work. The predominance of white donors in this study may reflect racial differences in knowledge about donation, attitudes toward donation, and social norms surrounding organ donation. For example, African American and European populations exhibit many differences in these three realms and African Americans tend to have lower rates of donation (Morgan, Miller, & Arasaratnam, 2003).

Limitations

There are several important limitations of this study. This is a qualitative, descriptive study that aims to describe one aspect of interviews conducted with NDDs. Discussion of media in these interviews was incidental and unprompted. Subjects were not surveyed about the role media and events played in their process of kidney donation. Subjects discussed media’s role in donation after questions such as “how did you decide to donate your kidney?”

As such, data can be used to attain a rough measure of how many donors used each form of media, but not to attain a quantitative assessment of exactly how many donors used each form of media. Additionally, the participants were not queried as to what specific aspect of the media resource moved them to donate. However, because participants were not asked directly about media use, this study provides a unique perspective: all references to the media were sufficiently important to the narrative of the NDD that they were discussed without any prompt.

While this study size was appropriate for qualitative research methodology, this issue should be explored in a larger population of NDDs, which would provide power for subsequent quantitative studies.

Conclusion

Non-directed donors are an invaluable resource to the kidney transplant world and this study reveals the significant role that media plays in their donations at all stages of the transplant process. The current study identified the types of media used by NDDs and the way in which those forms of media contributed to their donation. In depth study of the way media can shape the course of donation for a non-directed donor may provide new, more effective tools for recruiting NDDs in the future.

Practice Implications

This study provides preliminary evidence that non-directed kidney donors use media and informational resources throughout the process of kidney donation. Media can be used to reach out to potential NDDs and there is evidence that articles and television programming containing stories about donation may be the most effective form of outreach to potential donors. Informational resources are heavily utilized by NDDs and more data is needed to determine how these resources can be made more helpful to individuals navigating the donation process. In the period after transplantation, NDDs frequently become advocates for living kidney donation and they often use media outlets for that advocacy. Providing opportunities for NDDs to advocate for living donation on the web, through video content or written content may allow for these NDDs to become more effective proponents of living donation. Lastly, NDDs should be provided forums in which to connect with other donors or their recipients, as this is how many NDDs use the media after completing their donation. Further studies are needed in which NDDs are surveyed directly about their use of media and information resources, as well as the resources they found to be most helpful. This research might improve our outreach to potential donors and our facilitation of a straightforward donation process for NDDs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21NR014349.

Appendices

Appendix A: Classification of media and informational resources

| Internet sources | • Any references to activities done “online” |

| • References to known webpages e.g. the NKR website | |

| • References to “googling” | |

| • References to information obtained via email blast | |

| Articles | • References to any article written for published newspaper or magazine – even if accessed online. Includes, New York Times articles, New Yorker articles, school alumni magazines |

| Television programming | • Any reference to content seen on TV |

| • References to a known television show or program | |

| Social media | • References to known social media sites – e.g. Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn |

| • References to “social media” | |

| • References to “posts” of friends seen online | |

| • References to YouTube were excluded from this category and categorized as video content | |

| Events/speakers | • References to any event about transplants, kidney donation etc. |

| • References to speaking engagements or informational talks | |

| Video content | • References to any content in the form of video or film (e.g. documentary films) |

| • References to YouTube content | |

| Print content | • References to books, flyers, pamphlets etc. |

| Other | • Not otherwise classified (e.g. radio) |

References

- Alvaro E, Jones S, & Robles A (2006). Hispanic organ donation: impact of a Spanish-language organ donation campaign. Journal of the National Medical Association, 1, 28–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H (2008). Entertainment-Education and Recruitment of Cornea Donors: The Role of Emotion and Issue Involvement. Journal of Health Communication, 13, 20–36. doi:10.1080/10810730701806953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron Massie, Alexander Stewart, Montgomery Benavides, Fleming, et al. (2013). Social Media and Organ Donor Registration: The Facebook Effect. American Journal of Transplantation, 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=v_GGAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=YVZrP7FCj6&sig=-nNQhuCDyDCTNaaH007bIPYs96s

- Conesa C, Zambudio AR, Ramírez P, Canteras M, Rodríguez M, & Parrilla P (2004). Influence of different sources of information on attitude toward organ donation: a factor analysis. Transplantation Proceedings, 36, 1245–1248. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K, Brady R, & Marson L (2014). A “smarter” way to recruit organ donors? Transplantation, 97, e16–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CL (2011). How to increase living donation. Transplant international: official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation, 24, 344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeley TH, & Servoss TJ (2005). Examining College Students Intentions to Become Organ Donors. Journal of Health Communication, 10, 237–249. doi:10.1080/10810730590934262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeley TH, & Vincent D (2007). How Organ Donation Is Represented in Newspaper Articles in the United States. Health Communication, 21, 125–131. doi:10.1080/10410230701307022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C, Roman D, Garvey C, Kahn J, & Matas A (2004). Twenty‐Two Nondirected Kidney Donors: An Update on a Single Center’s Experience. American Journal of Transplantation, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison TR, Morgan SE, & Chewning LV (2008). The Challenges of Social Marketing of Organ Donation: News and Entertainment Coverage of Donation and Transplantation. Health Marketing Quarterly,25, 33–65. doi:10.1080/07359680802126079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosicki GM (1993). Problems and Opportunities in Agenda-Setting Research. Journal of Communication,43, 100–127. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01265.x [Google Scholar]

- MacFarquhar L (2009). The kindest cut: what sort of person gives a kidney to a stranger? New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19701991 [PubMed]

- Maple H, Chilcot J, Burnapp L, Gibbs P, Santhouse A, Norton S, Weinman J, et al. (2014). Motivations, outcomes, and characteristics of unspecified (nondirected altruistic) kidney donors in the United Kingdom. Transplantation, 98, 1182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloney G, & Walker I (2000). Messiahs, Pariahs, and Donors: The Development of Social Representations of Organ Transplants. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30, 203–227. doi:10.1111/1468-5914.00126 [Google Scholar]

- Matas A, Garvey C, Jacobs C, & Kahn J (2000). Nondirected Donation of Kidneys from Living Donors. New England Journal of Medicine, 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher ML, Veale JL, Javaid B, Leeser DB, Davis CL, Hil G, & Milner JE (2013). Kidney transplant chains amplify benefit of nondirected donors. JAMA Surgery, 148, 165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE, & Cannon TE (2003). African Americans’ knowledge about organ donation: Closing the gap with more effective persuasive message strategies. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95, 1066–1071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE, Miller JK, & Arasaratnam LA (2003). Similarities and Differences Between African Americans and European Americans Attitudes, Knowledge, and Willingness to Communicate About Organ Donation1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 693–715. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01920.x [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE, Harrison TR, Long SD, Afifi WA, Stephenson MS, & Reichert T (2005). Family discussions about organ donation: how the media influences opinions about donation decisions. Clinical Transplantation, 19, 674–682. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE, Harrison TR, Chewning L, Davis L, & Dicorcia M (2007). Entertainment (Mis)Education: The Framing of Organ Donation in Entertainment Television. Health Communication, 22, 143–151. doi:10.1080/10410230701454114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE, Harrison TR, Afifi WA, Long SD, & Stephenson MT (2008). In Their Own Words: The Reasons Why People Will (Not) Sign an Organ Donor Card. Health Communication, 23, 23–33. doi:10.1080/10410230701805158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE (2009). The intersection of conversation, cognitions, and campaigns: The social representation of organ donation. Communication Theory, 19, 29–48. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01331.x/full [Google Scholar]

- Quick BL, Meyer KR, Kim DK, Taylor D, Kline J, Apple T, & Newman JD (2007). Examining the association between media coverage of organ donation and organ transplantation rates. Clinical Transplantation, 21, 219–223. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick B, LaVoie N, Morgan S, & Bosch D (2015). You’ve got mail! An examination of a statewide direct‐mail marketing campaign to promote deceased organ donor registrations. Clinical Transplantation, 29, 997–1003. wiley. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubens AJ, Oleckno WA, & Cisla JR (1998). Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of college students regarding organ/tissue donation and implications for increasing organ/tissue donors. College Student Journal, 32, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Sack K (n.d.). 60 lives, 30 kidneys, all linked. New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- Salim A, Ley E, Berry C, Schulman D, Navarro S, Zheng L, & Chan L (2014). Increasing Organ Donation in Hispanic Americans: The Role of Media and Other Community Outreach Efforts. JAMA Surgery, 149, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2017, January 12). Retrieved September 13, 2017, from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/

- Studts JL, Ruberg JL, McGuffin SA, & Roetzer LM (2010). Decisions to register for the National Marrow Donor Program: rational vs emotional appeals. Bone marrow Transplantation, 45, 422–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice, 2. Routledge. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QRsFDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=K9KSx0lftp&sig=KK25B3Dd8cObPeYgaP8HDGdLxpQ

- Tian Y (2010). Organ donation on Web 2.0: content and audience analysis of organ donation videos on YouTube. Health communication, 25, 238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. highwire. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderKnyff J, Friedman D, & Tanner A (2014). Framing Life and Death on YouTube: The Strategic Communication of Organ Donation Messages by Organ Procurement Organizations. Journal of Health Communication, 20, 1–9. taylorfrancis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield MA, Loken B, & Hornik RC (2010). Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet (London, England), 376, 1261–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AD, Robbins ML, & Peipert JD (2016). Educating Prospective Kidney Transplant Recipients and Living Donors about Living Donation: Practical and Theoretical Recommendations for Increasing Living Donation Rates. Current Transplantation Reports, 3, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman A, Robbins M, Paiva A, Peipert J, Kynard-Amerson C, Goalby C, Davis L, et al. (2014). Your Path to Transplant: a randomized controlled trial of a tailored computer education intervention to increase living donor kidney transplant. BMC Nephrology, 15, 166 BMC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]