Abstract

Background: Significant health disparities are present in Marshallese adults residing in the United States, most notably a high incidence of type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions. There is limited research on medication adherence in the Marshallese population. Objective: This study explored perceptions of and experiences with medication adherence among Marshallese adults residing in Arkansas, with the aim of identifying and better understanding barriers and facilitators to medication adherence. Methods: Eligible participants were Marshallese adults taking at least one medication for a chronic health condition. Each participant completed a brief survey and semistructured interview conducted in Marshallese by a bilingual Marshallese staff member. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated from Marshallese to English. Qualitative data were coded for a priori and emergent themes. Results: A total of 40 participants were included in the study. The most common contributing factor for nonadherence was forgetting to take medication (82%). A majority of participants (70%) reported difficulty paying for medicine, 45% reported at least one form of cost-related nonadherence, and 40% engaged in more than one cost-related nonadherence practice. Family support and medication pill boxes were identified as facilitators for medication adherence. The majority of the participants (76.9%) stated that they understood the role of a pharmacist. Participants consistently desired more education on their medications from pharmacy providers. Conclusion: This is the first study to explore barriers and facilitators to medication adherence among Marshallese patients. The findings can be used to develop methods to improve medication adherence among Marshallese.

Keywords: medication adherence, cost-related nonadherence, Pacific Islander, pharmacist

Introduction

The United States has seen a rapid increase in the Pacific Islander population, with the most rapid growth occurring in southern states.1,2 Arkansas, which increased by 197% from 2000 to 2016,3,4 now has the largest population of Marshallese in the continental United States.2 Marshallese migrants from the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) are the most common Pacific Islander population residing in Arkansas. The RMI was a territory of the United States and the primary site of the US nuclear testing program from 1946 to 1958.5 In 1986, the RMI became an independent nation but now has a Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the United States. The COFA allows Marshallese migrants to travel, work, and reside in the United States without a visa and allows for US military control of the region.6 After the COFA agreement, Arkansas attracted Marshallese migrants looking for employment and educational opportunities, which led to the Marshallese population’s rapid growth in the state.

The Marshallese community faces significant health disparities7-10 and higher rates of chronic diseases than the US general population.10-14 A recent study of Marshallese adults in Arkansas found that 38.4% of participants had a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level indicative of diabetes (≥6.5%), and 32.6% had prediabetes (5.7% to 6.4%).15 Furthermore, 41.2% had hypertension and 39.1% had prehypertension.15 The study found more than half of those with biometric readings indicative of diabetes and hypertension had not been previously diagnosed by a health care provider.15

The lack of care is due in part to COFA migrant exclusion from Medicaid in 1996,16-19 which has resulted in a large number of uninsured Marshallese. Initially after the signing of the COFA in 1986, Marshallese migrants to the United States were eligible for Medicaid and other federal programs.6 However, the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act excluded COFA migrants from the “qualified immigrants” category eligible for Medicaid.17,20,21 State governments can extend Medicaid coverage to COFA migrants through state funds, but Arkansas has not extended coverage to COFA migrants residing in state.17,22

Medication adherence is a well-documented, crucial component of successful chronic disease management.23-25 Ethnic minority groups show lower rates of medication adherence and face a variety of barriers to successful medication adherence.26-30 In particular, minority groups face personal, economic, social, and cultural barriers.26-30 There are few studies on medication adherence among Pacific Islanders; however, available studies found that Pacific Islanders encounter sociocultural barriers, including a lack of understanding of chronic disease management, financial concerns, and cultural practices that influence medication adherence.31-34 While there are not specific studies on medication adherence among the Marshallese, published studies in this population document lower treatment adherence among those with a diabetes diagnosis than among non-Marshallese populations with a diabetes diagnosis, exacerbating the significant health disparities faced by the Marshallese community.35,36

This study explored perceptions of and experiences with medication adherence among Marshallese adults, with the aim of identifying and better understanding barriers and facilitators to medication adherence among those with a chronic health condition. The study is a part of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) initiative between the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and the Marshallese community in Arkansas.37 This CBPR partnership works to address the health disparities in the Arkansas Marshallese community.38 Community stakeholders have identified chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, as a top health concern.39 The study will contribute to future patient-centered interventions to improve medication adherence among Marshallese patients.40

Methods

Research Method and Approach

This study utilized the mixed-methods design of concurrent triangulation to explore the perceptions of and experiences with barriers and facilitators to medication adherence among Marshallese patients with a chronic disease living in Arkansas.41-46 As is typical in mixed-methods concurrent triangulation designs, qualitative and quantitative data were collected in one simultaneous phase. The quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed independently, and the results of each were combined and presented together. This design allowed the research team to corroborate findings across both types of data, compensating for potential weaknesses in either type of data and resulting in better understanding of the barriers and facilitators to medication adherence in the study population.

Study Setting

Participants were recruited from the UAMS North Street Clinic, which serves Marshallese patients living in Arkansas who have limited access to health care services. Bilingual Marshallese staff and community health workers (CHWs) are part of the clinic team, assisting patients and health care providers to ensure all services are culturally appropriate and communicated effectively. CHWs also connect patients with community services and help them navigate the health care system. The study was implemented in the clinic by bilingual Marshallese staff who were provided with study specific training, including consent procedures, interview facilitation skills, quality control procedures, confidentiality, data security, and human subjects protection.

Recruitment

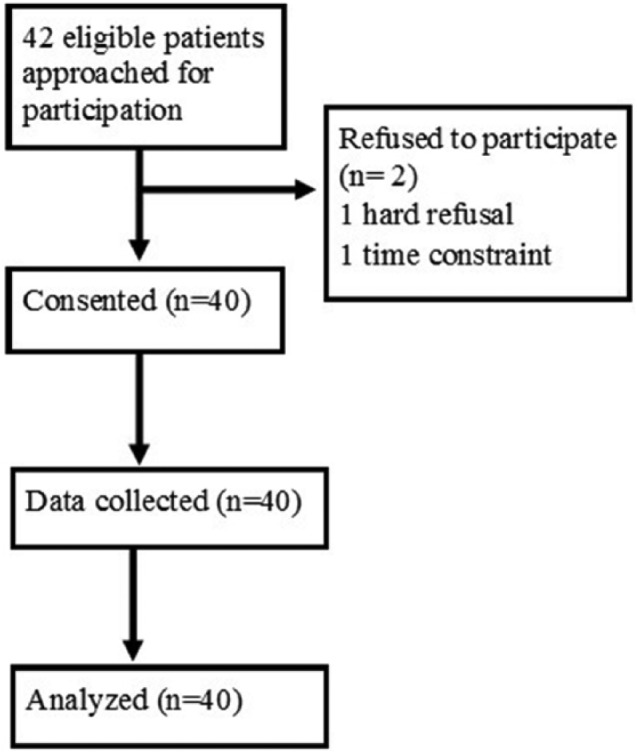

Individuals were eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years of age, self-reported Marshallese, and prescribed one or more prescription medications for a chronic health condition. Recruitment occurred between June 16, 2017, and August 10, 2017. Potential participants were approached during regularly scheduled clinic visits by bilingual Marshallese staff who provided information about the study and asked if they were interested in participating. A total of 42 eligible patients were approached; 40 agreed to participate, and 2 declined (ie, one patient refused, and one patient reported not having enough time) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study recruitment flow diagram.

Consent

Patients who agreed to participate were asked to provide informed consent to join the study. Study staff reviewed consent information orally, provided a written study information sheet to potential participants, and gave them the opportunity to ask questions about the study. All oral and written study information was provided in participants’ language of choice (English or Marshallese). The study was reviewed and approved by the UAMS Institutional Review Board (#206483). Participants were provided a $20 gift card as compensation for their participation.

Data Collection

Participants completed a short survey that included questions about demographic characteristics, health insurance coverage, health status, and medication adherence (see Tables 1 and 2). Survey questions were adapted from the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey47 and the Adherence to Refills and Medication Scale.48 Following the survey, participants took part in a qualitative interview designed to collect information related to participants’ perceptions and experiences with their medication and adherence to medication. The semistructured interview guide allowed participants to speak in-depth about their perceptions and experiences while also ensuring consistency of topics across all interviews. All interviews were conducted in Marshallese by Marshallese study staff trained in qualitative interviewing techniques. Each interview lasted approximately 10 to 20 minutes. All interviews were audio recorded. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and then translated from Marshallese to English by bilingual study staff.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 40)a.

| n (%) or Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Age | 53.08 ± 9.57 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (25.0) |

| Female | 30 (75.0) |

| Education | |

| No high school diploma | 24 (60.0) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 12 (30.0) |

| Some college or college graduate | 4 (10.0) |

| What is the primary source of your health care coverage? | |

| Plan purchased through employer | 10 (25.0) |

| Plan you or another family member bought on your own | 3 (7.5) |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 1 (2.5) |

| No coverage | 26 (65.0) |

| How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself? | |

| Extremely | 6 (15.0) |

| Quite a bit | 6 (15.0) |

| Somewhat | 1 (2.5) |

| A little | 9 (22.5) |

| Not at all | 18 (45.0) |

| Have you been admitted to the hospital in the last 12 months?b | 14 (35.0) |

| Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional EVER told you that you had any of the following: . . ?c | |

| Heart attack | 4 (10.0) |

| Angina or coronary heart disease | 7 (17.5) |

| Stroke | 4 (10.0) |

| Asthma | 6 (15.0) |

| Cancer | 2 (5.0) |

| COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis | 3 (7.5) |

| Some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia | 5 (12.5) |

| A depressive disorder, including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression | 14 (35.0) |

| Kidney disease | 5 (12.5) |

| Diabetes | 38 (95.0) |

| How old were you when you were told you have diabetes? | 43.18 ± 9.09 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Valid percentages only; missing data excluded. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Number and percent of participants that answered affirmatively.

Participants allowed to select multiple response options.

Table 2.

Survey Responses (N = 40)a.

| n (%) or Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| How many medications do you take every day? | 3.18 ± 1.62 |

| Do you understand why you are taking your medicine?b | 40 (100.0) |

| Do you believe the medicine will help you?b | 39 (97.5) |

| Have you ever felt like your medication makes you feel bad?b | 9 (22.5) |

| Have you ever stopped taking your medication before the doctor told you to stop taking it?b | 10 (25.0) |

| When you start feeling better do you stop taking your medicine(s)?b | 7 (17.5) |

| Do you ever forget to take your medicine(s)?b | 33 (82.5) |

| Did you forget to take your medicine anytime this week?b | 20 (50.0) |

| How often do you forget to take your medicine(s)? | |

| All the time | 3 (7.5) |

| Sometimes | 23 (57.5) |

| Never/rarely | 14 (35.0) |

| What do you use to help you remember to take your medicine?c | |

| Pill boxes | 22 (55.0) |

| Family | 20 (50.0) |

| Leave somewhere visible/convenient | 10 (25.0) |

| Calendar | 9 (22.5) |

| Alarms | 4 (10.0) |

| Phones | 1 (2.5) |

| When you are away from home on a trip have you forgotten to bring your medicine(s)?b | 14 (35.0) |

| During the past 12 months were any of the following true for you?c | |

| Skipped medication doses to save money | 15 (37.5) |

| Took less medicine to save money | 5 (12.5) |

| Delayed filling a prescription to save money | 17 (42.5) |

| Engaged in more than one cost-related nonadherence behavior | 16 (40.0) |

| Do you have trouble paying for your medicine?b | 28 (70.0) |

| Have you asked your doctor for a lower cost medication to save money?b | 10 (25.0) |

| Do you know the role of a pharmacist?b | 30 (76.9) |

| Do you ask your pharmacist questions?b | 26 (65.0) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Valid percentages only; missing data excluded. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Number and percent of participants that answered affirmatively.

Participants allowed to select multiple response options.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics for all demographic and close-ended health related questions from the preinterview survey were analyzed. A coding template was used to analyze the qualitative interview.49,50 Two experienced qualitative researchers developed an a priori, preliminary coding template with deductive domains that reflected the main focus of the study, including participants’ (1) general understanding, perceptions, and experience with medication; (2) factors related to nonadherence; (3) facilitators of medication adherence; and (4) understanding the role of and experience with a pharmacist. The research team coded the qualitative data and extracted data from the transcripts for additional analysis. Themes emerged within the broader a priori categories. These emergent themes were coded and incorporated into the coding template. Representative quotes from the interviews were inserted under each thematic domain in the coding template. The research team reviewed each iteration of the coding template to ensure analytic rigor and reliability and confirmed the data and quotes were extracted to the proper domain. A summary of the qualitative responses is provided, including representative quotes from participants’ responses.

Results

A total of 40 eligible patients were enrolled in the study. Table 1 presents participant characteristics. The majority of participants (75%) were female. Participants’ average age was 53 years, with an age range of 34 to 72 years. Sixteen participants (40%) reported they had graduated high school. Almost half of the participants (45%) reported feeling not at all comfortable completing medical forms independently. Most participants (65%) did not have health insurance. Thirty-eight participants (95%) reported being told they have diabetes.

General Understanding, Perceptions, and Experience With Medication

Table 2 presents survey responses. The mean number of medications each participant reported taking was 3.18 (SD = 1.62). All participants reported an understanding of why they were taking their medication(s). With the exception of one participant, all others (97.5%) believed their medication was helping them; however, 22.5% believed their medication was making them feel bad.

When participants were asked if they believed their medication was helping them, participants voiced they could “feel” their medications working. “Because I feel better now that I’m taking them [medications], and I believe that I will live a longer life” (Participant [P] 06). Another reported they could “feel it working, I feel better after I’ve been on medications” (P07). The word “feel” was used by almost every participant when asked if they believed their medication was working. Participants stated “while I’m taking them, I feel the difference. I feel better” (P13), and “I feel stronger now that I’m taking them [medication]” (P21). Other participants associated their medication(s) with clinical results, stating that they believed their medication was working “because of the good result that I see when I check my blood sugar and blood pressure while on medication” (P18) and “because my blood sugar is lower now from the meds” (P34).

While most stated that they believed their medication was helping them, some of the same participants expressed concerns with taking their medication. When asked specifically if they were scared to take their medication, some commented “Yes, scared of overdosing or being poisoned” (P01). Others reported their fear was predicated on concerns voiced by family or community members, citing they were scared because “other people criticize my meds” (P05) and “they tell me that the medicines are poisonous and will hurt me” (P24). Several participants explained that family members had voiced concerns. “They’re saying that the meds will make me more sick” (P02); “A lot of people tell me that they are poisonous” (P38); and “they say that my meds are bad and too strong” (P40). Participants also reported hearing their medications could cause bodily harm and would “ruin their kidneys . . . people are saying that they’re scared to take their medicines because they will damage their kidneys” (P08). Some participants even explained that family members “give me negative feedback and try to prevent me from taking my medicines” (P30).

Despite concerns participants heard from their family or community members, most reported they relied on their own experience and belief that their medication was helping. Participants said they hear “that the [medications] are not good for me to take, but I haven’t felt anything bad” (P01). Others stated,

I used to be scared of taking meds before when I didn’t understand them, but now I’m okay taking them [medication]. Now that they’ve been explained to me, and I see good results after taking them, I’m very happy now. (P13)

Another explained,

I feel the difference since I came from the Marshall Islands. I used to skip taking my meds from the Marshall Islands because I wasn’t sure if they were good for me, but I’m very consistent with my meds and now I feel better. (P23)

Factors Contributing to Nonadherence

When asked about nonadherence behaviors, 25% of participants reported they stopped taking their medication before the doctor told them to stop taking it, and 17.5% stated they stopped taking their medication when they started feeling better. The most commonly reported contributing factor to nonadherence was forgetting to take their medication, with 82.5% reporting they forget to take their medication and 50% reporting they forgot to take their medication within the past week. Qualitative responses regarding nonadherence were also dominated by participants’ discussion about forgetting medication. Some participants simply commented “I forget” (P16) and “Busy and forget” (P20). As one participant elaborated,

I really want to save my life but sometimes I’m really busy. I wake up in the morning, grab my purse without putting them in it, and rush out the door for work without taking them. I’m gone for the whole day and usually return when it’s bedtime and miss the whole day’s doses because I get home late at night. (P27)

When asked about cost-related nonadherence, 45% reported engaging in at least one nonadherence behavior to save money and 40% reported engaging in more than one nonadherence behavior to save money. These included skipping a medication dose (37.5%), taking less medication than prescribed (12.5%), and delaying medication refills (42.5%). Qualitative dialogue also illuminated concerns with the cost of medications. “Sometimes I cannot pick [medication] up from the pharmacy on time because I don’t have money” (P37), and “I don’t have enough money to buy [medication]” (P39). Overall, 70% reported trouble paying for medications. While cost-related nonadherence was high among participants, only 25% had asked their doctor for a lower cost medication.

While we did not include a quantitative question related to transportation, qualitative responses revealed that 12.5% of participants reported not having a ride and not having money for transportation as a factor for nonadherence, stating “sometimes I don’t have a ride, and sometimes I don’t have money for fuel” (P28). Others described that the lack of transportation made them feel helpless. As one participant explained, “When I run out of medicine I will go pick them up if I get a ride. And if you don’t have a ride then what do you do? Nothing, I can’t do anything. . . . I’m helpless” (P40).

Facilitators of Medication Adherence

When participants were asked what they use to help them remember to take their prescription medication, pill boxes (55%) and family support (50%) were the most common responses. Qualitative responses were also dominated by discussion of family support for remembering to take their prescription medication: “My family reminds me” (P05), “my wife and I remind each other” (P26), “I ask my family members to remind me” (P19), “my wife reminds me all the time” (P17), and “my kids remind me” (P21).

Participants also commented that support from family helped them overcome financial and transportation barriers, stating, “My family picks [prescription medications] up for me” (P11), “my brothers drives me [to the pharmacy]” (P19), and “my granddaughter picks them up for me” (P34). Others elaborated, “My sister helps drive me to the pharmacy . . . it’s far from my house and people drive me there” (P40) and “the pharmacy is far from my house so my son drives me there” (P18). Participants also cited “family support” (P08) to help pay for prescription medication as another facilitator to overcome cost-related nonadherence.

While a quantitative question about CHWs was not asked during the interview, qualitative responses found that participants relied on their assistance to help them navigate the health care system and get their prescription medication refilled. Participants stated that they “call the community health workers to help” (P03) and “I inform the community health workers that I’m out of medicine and they help me get them” (P27).

Understanding the Role of and Experience With a Pharmacist

When asked if they knew the role of a pharmacist, more than three quarters (76.9%) stated they did understand the role of a pharmacist. When asked to elaborate on the role of a pharmacist, the vast majority of participants described the pharmacist’s role as providing prescription medication. Participants commented that pharmacists “provide my medicines so I can take them” (P18), “I just know that he provides my medicine” (P19), and “I think they are responsible for making sure that I get the right medicine” (P29).

Participants also described that pharmacists help them remember when to pick up their prescription medication and explain how to properly take the prescription medication, stating, “My pharmacist . . . calls to remind me to pick up my refills and she explains them to me” (P02) and that pharmacists “explain how to take my meds, when to refill or not to refill, and remind me on how to take all my medicine, how much they cost, and stuff like that” (P26). Other participants described an expanded role for pharmacists such as to “help us to stay healthy” (P06) and “take care of our lives” (P38).

When probed about whether or not they asked their pharmacist questions about prescription medications, 65% of participants reported doing so. As one participant elaborated, “It’s always good to have them repeat it so we can understand on how to take our medicine” (P26). When asked about the type of questions participants asked their pharmacist, several participants reported that they wanted to know “how much the [prescription medication] cost” (P03). In addition, participants wanted to know “differences between each medicine and why there are changes in my medications and names” (P07). Some went on to elaborate about confusion over the way the prescription medications looked, the differences in brands, and differences in dosages. “I ask [pharmacists] about the differences between medicines. Why there are changes in my medications with different brands, different doses and colors . . . differences in price of my medicine” (P32).

Participants who did not ask questions stated they did not fully understand their prescription medication. “I would go home without totally understanding my meds” (P13). Some reported being reluctant or afraid to ask question. “I never ask questions . . . because there’s too many people there and so I’m afraid to ask” (P30).

A consistent theme among participants was a desire to better understand the ingredients of their medications. One participant stated,

What are these medicines made from, metformin and glipizide? Since we grew up with herbal medicine and don’t understand about Western medicine, I would like to know how they were made . . . how they came up with the idea to make them, and what they’re made of. (P08)

When asked what pharmacists could do to help Marshallese patients better understand their prescription medication, all participants stated that they wanted the pharmacist to better explain their prescription medication. Example statements included the following: “[Pharmacists] need to thoroughly explain [the prescription medications] to me” (P13), “[pharmacists] need to explain to me, tell me how strong my medicine is and how important it is to take my medicine” (P27), and “[pharmacists] have better understanding about my medicines, and they need to explain before giving them to me” (P18). Participants’ desire for additional explanations also extended to family members. Participants elaborated, “[Pharmacists] need to explain to my family too in order for them to help me in case I forget. [Family] are the ones that I will rely on” (P26). One participant explained,

[Pharmacists] need to make educational classes on the medicines that they give the Marshallese population and the diabetics . . . not just have us take [prescription medications] but explain it in more detail. So we have more knowledge of what we’re putting in our bodies. (P08)

Discussion

This study used the mixed-methods design of concurrent triangulation to explore the perceptions of and experiences with medication adherence among Marshallese patients living in Arkansas, with the goal of better understanding barriers and facilitators to medication adherence. Encouragingly, all of the participants self-reported they understood why they were taking their medication. The majority of participants believed their medications were helping them. Participants described predicating their evaluation of their medication on how it made them “feel.” While these results are overall encouraging, nearly a quarter of participants reported their medications were making them feel bad, and several participants recounted that members of their community and/or family discouraged them from taking medications because they could be harmful and even “poison.” Despite these findings, family members were a primary mechanism of support as they frequently reminded patients to take their medications, provided transportation, and helped overcome financial barriers. These findings are consistent with a growing body of literature that shows the importance of family support for patients with a chronic illness to successfully achieve medication adherence,51-53 especially among minority communities and collectivist cultures.51,54-64 This study’s findings contribute to a better understanding of how family members in Marshallese communities may engage in both supportive and nonsupportive behavior regarding medication adherence for chronic conditions.

The cost of medications was a major concern, with 70% of participants reporting cost as a barrier and 47.5% reporting at least one cost-related nonadherence practice. Prior studies have shown cost-related barriers as being significant for patients with type 2 diabetes or other chronic conditions.65-77 Additionally, a study looking specifically at Pacific Islander communities found cost-related barriers to be a significant cause of nonadherence.78 The present study contributes to our understanding of cost-related nonadherence in the Marshallese community and suggests that cost-related nonadherence may be higher in the Marshallese community compared to other populations.

The most common type of nonadherence among participants was simply forgetting to take their medication, with 82% reporting ever missing a dose and 50% reporting missing a dose in the past week. Similar rates (76%) for forgetfulness of taking medications have been reported in the literature for underserved populations.79

It was notable that 76.9% stated they understood the role of a pharmacist. Previous literature has demonstrated less pharmacist utilization or dissatisfaction with the pharmacist or pharmacy services in minority ethnic groups compared with the rates reported by the Marshallese participants in this study.80,81 More than half (65%) of participants in this study did ask their pharmacist questions, and the qualitative responses revealed that vast majority wanted to have explanations from their pharmacist. Participants desired information about their medication, dosage, cost, and timing, and most notably, they also wanted information about the natural compounds that make up the medication.

Strengths and Limitations

This exploratory study was limited by recruiting all participants from a single clinic. The clinic in which the study took place integrates CHWs and pharmacy providers as part of the clinical team. Cultural competency training is required for all team members; therefore, participants’ high level of understanding about why they were taking medications, understanding of the pharmacists’ role in managing their health, and propensity to ask their pharmacist questions may not be the same as patients from other clinics. The small sample size also limits the generalizability of the study. However, analysis of the transcripts showed that qualitative saturation was reached after 26 participants, with the additional participants adding to the contextual richness, suggesting the sample size was appropriate for this study. The mixed-methods design of concurrent triangulation was a strength that allowed for robust data collection and contextualization of findings across 2 different types of data. Several topics, including transportation, CHWs, and extent of family influence, emerged during the qualitative phase that may not have been identified using only a quantitative survey. While the study does have limitations, it is the first to examine medication adherence among Marshallese and provides a significant contribution to the literature.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

The study is part of the authors’ CBPR collaborative with the Marshallese community. The CBPR team, which includes Marshallese stakeholders and health care providers (pharmacists, physicians, and nurses), has developed recommendations for policy and practice based off exploratory findings of this study. The findings of this study and the recommendations for policy and practice will be disseminated back to the Marshallese community and health care providers who care for the Marshallese community. Additionally, the CBPR team will use the data to design patient-centered interventions.

Participants reported a desire for more education about their medications, including use for chronic conditions and information on the natural compounds the medications consist of. Because of the low educational attainment and low health literacy reported, health care providers should use appropriate terminology and utilize a teach-back or pictorial image method for the patient and/or patient’s caregiver to ensure understanding. These educational strategies have been shown to increase knowledge in other low health literacy groups, specifically among those with chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes.82 Health care providers should engage family members or caregivers in medication education and ask if more information on the chemical properties of the medication is desired, as this was a recurring theme discussed in the qualitative responses.

Simply forgetting to take their medication was reported by most participants. Medication adherence tools including pillboxes should be encouraged by health care providers. Furthermore, phone applications and text message reminders should be explored as a tool to help patients remember to take their medication. While results of previous studies of medication reminder phone applications and text message reminders have been mixed in other populations,83-86 future research is warranted to determine what adherence tools may be most helpful and effective with the Marshallese population.

While there were no specific survey questions on transportation, it was described as a barrier by some participants in the qualitative interview. Therefore, information should be provided to Marshallese patients on delivery services provided by local pharmacies. A systematic review of diabetic patients utilizing mail order compared to local retail pharmacies found that those using mail order pharmacies had an increase in adherence of ~8%; however, most of the studies assessed adherence by having a “pill in hand” rather than a “pill taken,” possibly overestimating the improvement in adherence.87

Cost was reported as a concern by 70% of participants, with 47.5% engaging in cost-related nonadherence practices. Health care providers can discuss generic medications or cheaper alternative therapies for patients. Additionally, the high uninsured rates demonstrate the access barrier for COFA migrants because of their exclusion from Medicaid. Ultimately, Medicaid access must be restored. Twenty-one bills have been introduced into Congress in an effort to restore COFA eligibility for Medicaid since 2001.88 The most recent bill “Restoring Medicaid for Compact of Free Association Migrants Act of 2015” was sponsored by Sen. Mazie K. Hirono (D-HI) and read twice before being referred to the Committee on Finance in May 2015.89 Health care providers can support and advocate for these bills, which would provide critical coverage for COFA migrants, including Marshallese.

Conclusion

This mixed-methods study provided insight on barriers and facilitators to medication adherence in the Marshallese in Arkansas. Throughout the interviews, the Marshallese participants expressed difficulty remembering to take their medications and described cost-related nonadherence behaviors to save money. Participants consistently desired family engagement with medication management and more education on their medications, including specific chemical contents. Further research is needed to determine which adherence tools may be most effective for the Marshallese population.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by the Translational Research Institute (Grant #1U54TR001629-01A1) through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This pilot study was also funded in part by a grant from the Sturgis Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or Sturgis Foundation.

ORCID iD: Jonell S. Hudson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8457-0582

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8457-0582

References

- 1. Grieco EM. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: Census 2000 Brief. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2001. https://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-14.pdf Accessed June 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hixson L, Hepler BB, Kim MO. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: 2010. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2012. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-12.pdf Accessed June 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Census Bureau. Profile of general demographic characteristics: 2000 census summary file 1 (SF-1) 100-percent data, Table DP-1. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- 4. US Census Bureau. ACS demographic and housing estimates: 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table DP05. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- 5. Barker HM. Bravo for the Marshallese: Regaining Control in a Post-Nuclear, Post-Colonial World. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6. 108th United States Congress. Compact of Free Association Amendments Act of 2003. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-108publ188/html/PLAW-108publ188.htm. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 7. Schiller J, Lucas J, Ward B, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat 10. 2012;10(252):1-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Look MA, Trask-Batti MK, Agres R, Mau ML, Kaholokula JK. Assessment and Priorities for Health & Well-Being in Native Hawaiians & Other Pacific Peoples. Honolulu, HI: Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research, University of Hawaii-Manoa; 2013. http://blog.hawaii.edu/uhmednow/files/2013/09/AP-Hlth-REPORT-2013.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moy KL, Sallis JF, David KJ. Health indicators of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in the United States. J Community Health. 2010;35:81-92. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9194-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. Profile: Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=65. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 11. Tung WC. Diabetes among Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2012;24:309-311. doi: 10.1177/1084822312454002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP, Baumhofer KN, Kaholokula JK. Cardiometabolic health disparities in native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:113-129. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okihiro M, Harrigan R. An overview of obesity and diabetes in the diverse populations of the Pacific. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 suppl 5):S5-71-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hawley NL, McGarvey ST. Obesity and diabetes in Pacific Islanders: the current burden and the need for urgent action. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:29. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0594-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McElfish P, Rowland B, Long C, et al. Diabetes and hypertension in Marshallese adults: results from faith-based health screenings. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:1042-1050. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0308-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McElfish P, Hallgren E, Yamada S. Effect of US health policies on health care access for Marshallese migrants. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:637-643. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McElfish PA, Purvis RS, Maskarinec CG, et al. Interpretive policy analysis: Marshallese COFA migrants and the Affordable Care Act. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:91. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saunders A, Schiff T, Rieth K, Yamada S, Maskarinec GG, Riklon S. Health as a human right: who is eligible? Hawaii Med J. 2010;69(6 suppl 3):4-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shek D, Yamada S. Health care for Micronesians and constitutional rights. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(11 suppl 2):4-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Medicaid restoration for compact of free association migrants. http://www.apiahf.org/policy-and-advocacy/policy-priorities/health-care-access/medicaid-restoration-compact-free-associati Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 21. United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Hawai’i; Korab V. Fink. http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2014/04/01/11-15132.pdf Accessed June 21, 2018.

- 22. Cook SL. The Affordable Care Act. What does it mean to Arkansans? http://docplayer.net/9227186-The-affordable-care-act-what-does-it-mean-to-arkansans-sandra-l-cook-mpa-consumer-assistance-specialist-arkansas-insurance-department.html Accessed June 21, 2018.

- 23. Burkhart PV, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35:207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ. 2006;333:15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38875.675486.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brundisini F, Vanstone M, Hulan D, DeJean D, Giacomini M. Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ differing perspectives on medication nonadherence: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:516. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mishra SI, Gioia D, Childress S, Barnet B, Webster RL. Adherence to medication regimens among low-income patients with multiple comorbid chronic conditions. Health Soc Work. 2011;36:249-258. doi: 10.1093/hsw/36.4.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jeragh-Alhaddad FB, Waheedi M, Barber ND, Brock TP. Barriers to medication taking among Kuwaiti patients with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1491-1503. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S86719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barton SS, Anderson N, Thommasen HV. The diabetes experiences of Aboriginal people living in a rural Canadian community. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13:242-246. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2005.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henderson LC. Divergent models of diabetes among American Indian elders. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2010;25:303-316. doi: 10.1007/s10823-010-9128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shaw JL, Brown J, Khan B, Mau MK, Dillard D. Resources, roadblocks and turning points: a qualitative study of American Indian/Alaska Native adults with type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2013;38:86-94. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stewart DW, Depue J, Rosen RK, et al. Medication-taking beliefs and diabetes in American Samoa: a qualitative inquiry. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:30-38. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wong M, Haswell-Elkins M, Tamwoy E, McDermott R, d’Abbs P. Perspectives on clinic attendance, medication and foot-care among people with diabetes in the Torres Strait Islands and Northern Peninsula Area. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13:172-177. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1854.2005.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Capstick S, Norris P, Sopoage F, Tobata W. Relationship between health and culture in Polynesia—a review. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1341-1348. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Norris P, Fa’alau F, Va’ai C, Churchward M, Arroll B. Navigating between illness paradigms: treatment seeking by Samoan people in Samoa and New Zealand. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:1466-1475. doi: 10.1177/1049732309348364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McElfish PA, Rowland B, Long CR, et al. Diabetes and hypertension in Marshallese adults: results from faith-based health screenings. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:1042-1050. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0308-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Felix H, Xiaocong L, Rowland B, Long CR, Yeary KHK, McElfish PA. Physical activity and diabetes-related health beliefs of Marshallese adults. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41:553-560. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.41.5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McElfish PA, Goulden PA, Bursac Z, et al. Engagement practices that join scientific methods with community wisdom: designing a patient-centered, randomized control trial with a Pacific Islander community. Nurs Inq. 2017;24(2), e12141. doi: 10.1111/nin.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McElfish PA, Moore R, Laelan M, Ayers BL. Using CBPR to address health disparities with the Marshallese community in Arkansas. Ann Hum Biol. 2018;45:264-27. doi:10.1080/03014460.2018.1461927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McElfish PA, Kohler P, Smith C, et al. Community-driven research agenda to reduce health disparities. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8:690-695. doi: 10.1111/cts.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuntz JL, Safford MM, Singh JA, et al. Patient-centered interventions to improve medication management and adherence: a qualitative review of research findings. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97:310-326. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bergman M. Advances in Mixed Methods Research: Theories and Applications. London, England: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3rd ed. London, England: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML, Hanson WE. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003:209-240. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Johnson RB, Onweugbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definitions of mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1:112-133. doi: 10.1177/1558689806298224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33:14-26. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033007014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhpi.html. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- 48. Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Development and evaluation of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) among low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health. 2009;12:118-123. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. King N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Cassell C, Symon G, eds. Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004:256-270. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nadin S, Cassell C. Using data matrices. In: Cassell C, Symon G, eds. Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004:271-287. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Family support, medication adherence, and glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1239-1245. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:207-218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miller TA, DiMatteo MR. Importance of family/social support and impact on adherence to diabetic therapy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:421-426. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S36368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tang TS, Brown MB, Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Social support, quality of life, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:266-276. doi: 10.1177/0145721708315680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burns KK, Nicolucci A, Holt RI, et al. ; DAWN2 Study Group. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs second study (DAWN2™): cross-national benchmarking indicators for family members living with people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30:778-788. doi: 10.1111/dme.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nicolucci A, Burns KK, Holt RI, et al. ; DAWN2 Study Group. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs second study (DAWN2™): cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30:767-777. doi: 10.1111/dme.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Peyrot M, Burns KK, Davies M, et al. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs 2 (DAWN2): a multinational, multi-stakeholder study of psychosocial issues in diabetes and person-centred diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:174-184. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Holt RI, Nicolucci A, Burns KK, et al. ; DAWN2 Study Group. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs second study (DAWN2™): cross-national comparisons on barriers and resources for optimal care—healthcare professional perspective. Diabet Med. 2013;30:789-798. doi: 10.1111/dme.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: a joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1372-1382. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Baig AA, Benitez A, Quinn MT, Burnet DL. Family interventions to improve diabetes outcomes for adults. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1353:89-112. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pamungkas RA, Chamroonsawasdi K, Vatanasomboon P. A systematic review: family support integrated with diabetes self-management among uncontrolled type II diabetes mellitus patients. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7:E62. doi: 10.3390/bs7030062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rintala TM, Jaatinen P, Paavilainen E, Astedt-Kurki P. Interrelation between adult persons with diabetes and their family: a systematic review of the literature. J Fam Nurs. 2013;19:3-28. doi: 10.1177/1074840712471899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mayberry LS, Rothman RL, Osborn CY. Family members’ obstructive behaviors appear to be more harmful among adults with type 2 diabetes and limited health literacy. J Health Commun. 2014;19(suppl 2):132-143. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.938840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bennich B, Røder M, Overgaard D, et al. Supportive and non-supportive interactions in families with a type 2 diabetes patient: an integrative review. Diebetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:57. doi: 10.1186/s13098-017-0256-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Patel MR, Piette JD, Resnicow K, Kowalski-Dobson T, Heisler M. Social determinants of health, cost-related nonadherence, and cost-reducing behaviors among adults with diabetes: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 2016;54:796-803. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Musich S, Cheng Y, Wang SS, Hommer CE, Hawkins K, Yeh CS. Pharmaceutical cost-saving strategies and their association with medication adherence in a Medicare supplement population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1208-1214. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Marcum ZA, Zheng Y, Perera S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported medication non-adherence among older adults with coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and/or hypertension. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9:817-827. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McHorney CA, Spain CV. Frequency of and reasons for medication non-fulfillment and non-persistence among American adults with chronic disease in 2008. Health Expect. 2011;14:307-320. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Piette JD, Beard A, Rosland AM, McHorney CA. Beliefs that influence cost-related medication non-adherence among the “haves” and “have nots” with chronic diseases. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:389-396. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S23111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1749-1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Piette JD, Wagner TH, Potter MB, Schillinger D. Health insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of care. Med Care. 2004;42:102-109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108742.26446.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zheng Z, Han X, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Do cancer survivors change their prescription drug use for financial reasons? Findings from a nationally representative sample in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1453-1463. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tseng CW, Tierney EF, Gerzoff RB, et al. Race/ethnicity and economic differences in cost-related medication underuse among insured adults with diabetes: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:261-266. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Briesacher BA, Gurwitz JH, Soumerai SB. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: a review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:864-871. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1829-1835. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tseng CW, Brook RH, Keeler E, Steers WN, Mangione CM. Cost-lowering strategies used by Medicare beneficiaries who exceed drug benefit caps and have a gap in drug coverage. JAMA. 2004;292:952-960. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Steinman MA, Sands LP, Covinsky KE. Self-restriction of medications due to cost in seniors without prescription coverage. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:793-799. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McElfish P, Long C, Payakachat N, et al. Cost-related nonadherence to medication treatment plans: Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey, 2014. Med Care. 2018;56:341-349. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Allen CG, Brownstein JN, Satsangi A, Escoffery C. Community health workers as allies in hypertension self-management and medication adherence in the United States, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E179. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Alzubaidi H, McNamara K, Versace VL. Predictors of effective therapeutic relationships between pharmacists and patients with type 2 diabetes: Comparison between Arabic-speaking and Caucasian English-speaking patients [published online November 23, 2017]. Res Social Adm Pharm. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Olenik NL, Gonzalvo JD, Snyder ME, Nash CL, Smith CT. Perceptions of Spanish-speaking clientele of patient care services in a community pharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11:241-252. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Negarandeha R, Mahmoodib H, Noktehdanb H, Heshmat R, Shakibazadeh E. Teach back and pictorial image educational strategies on knowledge about diabetes and medication/dietary adherence among low health literate patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2013;7:111-118. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hincapie AL, Gupta V, Brown SA, Metzger AH. Exploring perceived barriers to medication adherence and the use of mobile technology in underserved patients with chronic conditions [published online December 6, 2017]. J Pharm Pract. doi: 10.1177/0897190017744953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sugita H, Shinohara R, Yokomichi H, Suzuki K, Yamagata Z. Effect of text messages to improve health literacy on medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2017;79:313-321. doi: 10.18999/nagjms.79.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Nelson LA, Mayberry LS, Wallston K, Kripalani S, Bergner EM, Osborn CY. Development and usability of REACH: a tailored theory-based text messaging intervention for disadvantaged adults with type 2 diabetes. JMIR Hum Factors. 2016;3:e23. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.6029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bergner EM, Nelson LA, Rothman RL, Mayberry L. Text messaging may engage and benefit adults with type 2 diabetes regardless of health literacy status. Health Lit Res Pract. 2017;1:e192-e202. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20170906-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fernandez EV, McDaniel JA, Carroll NV. Examination of the link between medication adherence and use of mail-order pharmacies in chronic disease states. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:1247-1259. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.11.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Health care for COFA migrants. https://www.apiahf.org/resource/health-care-for-cofa-migrants/ Accessed March 21, 2018.

- 89. 114th United States Congress. Restoring Medicaid for Compact of Free Association Migrants Act of 2015. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1301 Accessed March 26, 2018.