Abstract

Background:

Infectious illness in the workplace places a substantial cost burden on employers due to productivity losses from employee absenteeism and presenteeism.

Aim:

Given the clear impacts of infectious illness on workplaces, this review aimed to investigate the international literature on the effectiveness and cost-benefit of the strategies non-healthcare workplaces use to prevent and control infectious illnesses in these workplaces.

Methods:

MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus with Fulltext and Business Source Complete were searched concurrently using EBSCO Host 1995–2016.

Findings:

Infection prevention and control strategies to reduce workplace infectious illness and absenteeism evaluated in the literature include influenza vaccination programs, use of alcohol-based hand sanitiser and paid sick days. While the reported studies have various methodological flaws, there is good evidence of the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in preventing workplace infectious illness and absences and moderate evidence to support hand hygiene programs.

Discussion:

Some studies used more than one intervention concurrently, making it difficult to determine the relative benefit of each individual strategy. Workplace strategies to prevent and control infectious illness transmission may reduce costs and productivity losses experienced by businesses and organisations related to infectious illness absenteeism and presenteeism.

Keywords: Infectious illness, absenteeism, presenteeism, productivity cost, infection prevention, influenza vaccination, hand hygiene, paid sick days

Background

There are limited recent data on infectious illness impacts in the workplace; however, those sources that are available indicate that employers have become increasingly aware of the cost burden of employee absenteeism and presenteeism (Berger et al., 2001; Brandt-Rauf et al., 2001). Absenteeism is defined as missed work days (Poston et al., 2011), while attending work while ill is termed presenteeism (Skagen and Collins, 2016). Feeney et al. (1998) estimated that 50–60% of all workplace absenteeism was caused by respiratory disorders or gastroenteritis. Globally, annual influenza incidence rates have been estimated at 5–10% in adults (World Health Organization, 2014). In workplaces, influenza incidence rates have been in the range of 12–23.7% (Mohren et al., 2005; Schanzer et al., 2011) depending on the timeframe being audited. Approximately 70% of employees with influenza are absent from work during their infection, which can result in an average loss of 3% of annual work hours (Mohren et al., 2005; Schanzer et al., 2011).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), almost 26 million employees in the United States of America (USA) were infected with H1N1 during the 2009 pandemic peak (Drago and Miller, 2010); 18 million took sick leave, eight million did not. As each employee with influenza who attends work is estimated to infect an additional 0.9 co-workers (Lovell, 2005), an estimated seven million H1N1 infections occurred due to presenteeism (Drago and Miller, 2010). Approximately 16% of influenza transmission is estimated to occur in the workplace (Edwards et al., 2016).

Annually, approximately 500 million non-influenza viral respiratory tract infections occur in the USA, resulting in 70 million lost workdays (Fendrick et al., 2003), while in the Netherlands, the incidence rate over three years was 50% and almost 30% of these took sick leave (Mohren et al., 2005). There is considerably less literature regarding gastroenteritis as a specific cause of absence. In the Netherlands, the gastroenteritis incidence rate was 10.1% during 1998–2001 and the absence rate was 45.3% (Mohren et al., 2005).

Infectious illnesses have considerable impacts on workplace productivity and costs. For example, in France and Germany, lost productivity related to infectious illnesses in the workplace cost an estimated $US10–15 billion per year (Lynd et al., 2005; “Economic and social…,” 2006). Associated costs due to influenza were $87.1 billion in the USA in 2003; $6.2 billion were attributed to productivity losses (Molinari et al., 2007). Lost productivity due to acute respiratory illness (ARI) in the USA accounts for as much as 75% of the total economic burden (Palmer et al., 2010). A 2003 study estimated that non-influenza viral respiratory illness resulted in an economic impact of $40 billion in the USA annually (Fendrick et al., 2003). For each influenza-like illness (ILI) episode, an average of 23.6 and 23.9 work hours were lost during the 2007/2008 and 2008/2009 influenza seasons, respectively (Tsai et al., 2014).

Associated costs of preventable illnesses typically exceed treatment costs (Fendrick et al., 2011; Goetzel et al., 2004). In the USA in 2003, the direct healthcare costs associated with influenza were $10.4 million, while the costs due to lost earnings and employee deaths were $16.3 million (Molinari et al., 2007). For the common cold in the USA during 1997, healthcare costs were $17 billion while economic costs were $22.5 billion (Fendrick et al., 2003).

The impact of, and costs associated with, presenteeism are also significant (Johns, 2010; Mohren et al., 2005). Sick employees demonstrate decreased reaction times and alertness, and increased anxiety, which decrease their efficiency at work (Smith et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2004). Ill employees assess their own efficiency at up to 45% lower than usual (Keech et al., 1998). The consequences of presenteeism include later serious and chronic illness, which could subsequently increase absenteeism (Hansen and Anderson, 2008; Johns, 2010; Kivimäki et al., 2005). A study by Bramley et al. (2002) found that the work hours lost and costs due to presenteeism exceeded those due to absenteeism and every cold resulted in an average loss of 8.7 h, 5.9 of which were due to presenteeism; costs related to the common cold for employers in the USA were $25 billion annually, $16.6 billion due to presenteeism.

Health-related workplaces such as hospitals are aware of the potential consequences of infectious illnesses, both to employees and patients, follow strict guidelines to prevent infection (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2010; Pratt et al., 2007) and have robust evidence-based infection prevention and control programs. Non-health workplaces are not bound by such guidelines and are less well informed on workplace infection prevention (Hansen et al., 2017). Given the clear impacts of infectious illness on workplaces, this review aimed to investigate the international literature on the effectiveness and cost-benefit of the strategies non-healthcare workplaces use to prevent and control infectious illnesses in these workplaces.

Methods

An integrative literature review (Whitmore and Knalf, 2005) was used to investigate these topics. While there are multiple approaches to reviewing the literature including systematic reviews, qualitative reviews and meta-analyses, ‘the integrative review method is the only approach that allows for the combination of diverse methodologies (for example, experimental and non-experimental research)’ and therefore is useful in evaluating the strength of the scientific evidence and identifying research gaps when there are few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to review (Whitmore and Knafl, 2005, p 546).

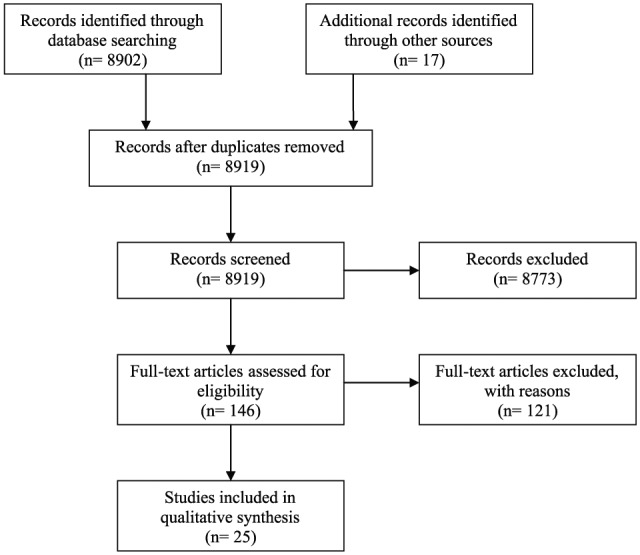

Ethical approval for this review was not required. MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus with Fulltext and Business Source Complete were searched concurrently using EBSCO Host, which eliminates duplicates. Inclusion criteria were any English language articles published between 1995 and 2016 pertaining to human adults. Any non-health workplaces and infection control measures were included in the review. Non-health workplaces were defined as workplaces that did not offer healthcare as their primary product. Search terms are listed in Table 1. Articles were selected that included at least one keyword from the two lists shown in Table 1. Reference lists of selected articles were also searched for additional relevant sources. Only research papers and reviews were considered for full text retrieval. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram for the search results.

Table 1.

Literature search keywords.

| List 1 | List 2 |

|---|---|

| glandular fever | absenteeism |

| influenza | work loss |

| common cold | productivity loss |

| gastro* | sickness absence |

| respiratory infection | worker absence |

| communicable disease | health absence |

| infectious illness | presenteeism |

| viral illness | work* |

| respiratory tract infection | |

| diarrhoea |

Wildcard symbol, to find words starting with the same letters.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of search results.

Quality assessment was performed after the papers were collected. Each paper was examined for methodological flaws that potentially induce bias (supplementary material appendices 1–4). Although not numerically weighted for scientific rigidity, papers were still described and compared accordingly.

Results

Twenty-five articles matching the search criteria were found. Seven pertained to hand hygiene and cough etiquette (supplementary material appendix 1), 17 examined influenza vaccinations (supplementary material appendices 2–4) and another theoretically examined paid sick leave as a method of preventing the spread of infection (Kumar et al., 2013). Comprehensive cost-benefit analyses were only performed for influenza vaccinations. Specific details of study design, sample size, findings and limitations are provided in supplementary material appendices 1–4.

Hand hygiene and cough etiquette

The seven hand hygiene studies used a variety of related interventions, including handwashing or the use alcohol-based hand sanitiser (ABHS), and education about, and/or reinforcement of, regular hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette (Hammond et al., 2000; Hübner et al., 2010; Mott et al., 2007; Savolain-Kopra et al., 2012; Stedman-Smith et al., 2015; Uhari and Möttönen, 1999; van Camp and Ortega, 2007) (supplementary material appendix 1). These studies included three cluster RCTs, two prospective interventional studies, and two with a pre-post design. Six examined infectious illness incidence rates and seven examined absenteeism rates following the introduction of hand hygiene measures. Those that examined infectious illness incidence found a significant reduction in incidence in the range of 6.7–31% overall and 11–50% for specific infections. Changes in absenteeism rates were not as consistent. For example, Mott et al. (2007) found a 44% reduction in absenteeism rates while Uhari and Möttönen (1999) found a 15% increase. Several studies demonstrated methodological inadequacies resulting in potential biases for example limited study duration, lack of blinding, insufficient sample recruitment and significantly different demographics between intervention and control groups (supplementary material appendix 1).

Influenza vaccinations

Studies evaluating the effect of influenza vaccination on workplace absenteeism were more common than hand hygiene studies. Nine studies—including two RCTs, four prospective and two retrospective observational studies, and one with a pre-post test design—found that influenza vaccination significantly decreased absenteeism demonstrating either a 0.15–3.0 day reduction in absences per employee or a 26–43% reduction overall depending on how the findings were presented (Abbas et al., 2006; At’kov et al., 2011; Leighton et al., 1996; Mixeu et al., 2002; Nichol et al., 1995, 2009; Olsen et al., 1998; Samad et al; 2006; Santoro et al., 2004) (supplementary material appendix 2). Three studies—including two RCTs, one prospective observational study and one prospective interventional study—yielded mixed results, finding significantly fewer absences due to one condition or in one season but not another (see supplementary material appendix 3) (Bridges et al., 2000; Campbell and Rumley, 1997; Nichol et al., 1999). Five studies found non-significant differences in absenteeism (Cohen et al., 2003; Dille, 1999; Millot et al., 2002; Morales et al., 2004; Spurzem, 1996) (supplementary material appendix 4). The direction of the non-significant differences was towards a reduction in absenteeism with one exception.

A number of the studies also examined influenza incidence. Eleven reported 24–79.9% fewer episodes of influenza and ILI compared with the unvaccinated group (Abbas et al., 2006; At’kov et al., 2011; Bridges et al., 2000; Dille, 1999; Leighton et al., 1996; Mixeu et al., 2002; Morales et al., 2004; Nichol et al., 1995, 1999, 2009; Santoro et al., 2004). Conversely, four found no significant differences in ILI incidence (Bridges et al., 2000; Millot et al., 2002; Morales et al. 2004; Spurzem, 1996).

Eleven studies also conducted cost-benefit analyses, nine of which (Abbas et al., 2006; Campbell and Rumley, 1997; Cohen et al., 2003; Dille, 1999; Morales et al., 2004; Nichol et al., 1995; Samad et al., 2005; Santoro et al., 2004) found influenza vaccination to be cost-effective (supplementary material appendices 2–4). Cost savings per vaccinated employee of €2.13–5.43, 200 Argentinian pesos and US$6.40–83.34 were reported. Conversely, one study found a net cost of US$11.17–65.69 across two seasons per employee compared to placebo even though the vaccine matched the circulating viral strains (Bridges et al., 2000). Nichol et al. (2003) concluded in their study that the mean break-even cost for the vaccine and its administration was US$43.07 per person vaccinated. Overall, these results suggest that worker vaccination programs may result in significant cost savings for employers in non-health related workplaces.

Paid sick leave

A simulated modelling study examined the effect of access to paid sick days (PSDs) on infectious illness incidence, presenteeism and absenteeism (Kumar et al., 2013). This study found that in a simulated influenza epidemic, 11.59% of influenza infections were due to workplace transmission and that 72% of these were due to presenteeism. Access to universal PSDs reduced workplace infections by 5.86% in this model; allowing employees with influenza to take one or two PSDs reduced workplace influenza infections by 25.33% and 39.22%, respectively (Kumar et al., 2013). This study however, was purely theoretical and made many simplifying assumptions, for example that employees are physically evenly dispersed and racially and sexually heterogeneous through the workplace. However, research has shown that this is generally not the case (Danon et al., 2012; Read et al., 2008).

Discussion

This review identified first that infectious illness in the workplace places a substantial cost and productivity burden on employers. The review also identified strategies that have been implemented by organisations to reduce or control infectious illness impacts and evaluations of the effectiveness of these strategies. Introduction of hand hygiene programs, including the use of ABHS, and influenza vaccination are the two most widely reported and evaluated strategies.

Six studies were found on the effect of hand hygiene on infectious illness rates and related absenteeism, excluding one primarily performed on students that additionally recorded teacher absence (Hammond et al., 2000). Among the intervention groups, significantly lower infectious illness incidence rates were found in all six studies while significantly lower absenteeism was found in three; however, the majority of these studies had some methodological inadequacies such as lack of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding, so positive results should be interpreted cautiously. The strongest studies methodologically (the three cluster RCTs) did not demonstrate a significant reduction in absenteeism; in fact, one demonstrated a significant increase in absenteeism in the intervention group, suggesting that while employers could adopt hand hygiene as a precautionary measure to prevent the spread of infection, it may not impact favourably on absenteeism. Having said this, one of the RCTs was impacted by the global hand hygiene education campaign associated with the H1N1 pandemic that began part way through the study; this could have affected the behaviour of the control group (Savolainen-Kopra et al., 2012).

The results of these studies also suggest that ABHS availability may decrease absenteeism, although doubt remains whether the addition of hand hygiene education and reinforcement further results in further decreases in absenteeism. Reviews conducted in home and community settings (Bloomfield et al., 2007) as well as elementary school settings (Meadows and Le Saux, 2004) have also found that various aspects of hand hygiene can be beneficial in decreasing infectious illness incidence and absenteeism; however, the quality of the available evidence is lacking due to poor methodological design (van de Mortel, 2008). Unfortunately, no cost-benefit analyses for hand hygiene and ABHS were found, so this remains an area that requires further research.

Influenza vaccination had stronger supporting evidence for efficacy than hand hygiene programs. Seventeen studies were conducted in a variety of workplace settings. Overall, infectious illness absenteeism in response to influenza vaccination declined significantly in nine studies and declined in at least one season or condition in another three studies among vaccinated workers. A further four studies found non-significant declines in absenteeism. Eleven of these studies also conducted cost-benefit analyses, with net savings in the range of US$6.40–83.34 (and savings of up to US$238–900 if operating costs are included) per vaccinated employee, although one study reported a net cost of US$11.17–65.69 per vaccinated employee across two seasons. However, methodological inadequacies are ubiquitous throughout these studies, with the majority failing to use randomisation and blinding. The strongest studies methodologically were more likely to demonstrate a significant reduction in absenteeism following vaccination. For example, 100% of the RCTs demonstrated a significant decline in absenteeism following vaccination versus 60% of prospective interventional studies, 50% of prospective observational studies and 50% of retrospective observational studies.

Overall, the results from these studies suggest that influenza vaccination programs may decrease infectious illness incidence and absenteeism, and may also result in significant cost savings for employers. This is similar to the conclusions made from recent Cochrane systematic reviews conducted in community and aged care settings; however, the potential benefits of vaccination in those reviews were not as optimistic as those of this review (Demicheli et al., 2014; Jefferson et al., 2012). While vaccines were found to be effective in preventing influenza in children over the age of two years, for younger children there was little evidence available (Jefferson et al., 2012). A very modest decrease in absenteeism and influenza symptoms was found in healthy adults including pregnant women (Demicheli et al., 2014). No conclusions could be drawn regarding the effects of vaccines on the elderly due to the generally low quality of available evidence (Jefferson et al., 2010). Neither of these reviews examined potential cost-benefits.

One of the limitations of this review is the difficulty in summarising the results of these very disparate studies. For example, cost savings were variously reported as cost savings per vaccinated employee, cost savings per lost workday, cost savings per dollar spent, cost savings by specific symptoms such as febrile illness, cost savings per vaccinated employee when presenteeism was accounted for and break-even costs for vaccination. Cost savings were also reported in US dollars, Argentinean pesos and Euros, although US dollars were the most common currency reported. Similarly, infectious illness incidence was sometimes reported as total percentage reduction or increase, or specific to particular conditions such as URI, ILI, gastrointestinal illness, febrile illness and serious febrile illness. Absenteeism was variously reported as percentage reduction in absenteeism, reduction in hours of absenteeism per new vaccinees and consecutive vaccinees, reductions in absent days per employee, percentage reduction in total lost workdays, reductions in lost workdays by specific conditions such as URI or febrile illness, days lost per 100,000 worked, reductions by season and reductions in pro rata sick days.

Conclusions

While hand hygiene and influenza vaccination have been identified as appropriate prevention methods, more awareness of effective strategies may reduce the infectious illness cost burden and improve employee health in non-health workplaces. Further research should involve more rigorous research regarding strategy efficacy and cost-benefits in order to ascertain if the generally positive outcomes outlined in this review are supported. More research also should be conducted in regards to workplace infectious illness practices as this review found this information lacking.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_1 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_2 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_3 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_4 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Griffith University librarian Katrina Henderson for her advice on the literature search protocol.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by a Griffith University postgraduate student stipend.

Peer review statement: Not commissioned; blind peer-reviewed.

ORCID iD: Stephanie Hansen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8952-2651

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8952-2651

References

- Abbas M, Fiala L, Tawfiq L. (2006) Workplace influenza vaccination in two major industries in Saudi Arabia: A cost benefit analysis. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association 81(1–2): 59–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- At’kov O, Azarov AV, Zhukov DA, Nicoloyannis N, Durand L. (2011) Influenza vaccination in healthy working adults in Russia: Observational study of effectiveness and return on investment for the employer. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 9(2): 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger ML, Murray JF, Xu J, Pauly M. (2001) Alternative valuations of work loss and productivity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 43(1): 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SF, Aiello AE, Cookson B, O’Boyle C, Larson EL. (2007) The effectiveness of hand hygiene procedures in reducing the risks of infections in home and community settings including handwashing and alcohol-based sanitizers. American Journal of Infection Control 35(10): S27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley TJ, Lerner D, Sarnes M. (2002) Productivity losses related to the common cold. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44(9): 822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt-Rauf P, Burton WN, McCunney RJ. (2001) Health, productivity, and occupational medicine. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 43(1): 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CB, Thompson WW, Meltzer MI, Reeve GR, Talamonti WJ, Cox NJ, Lilac HA, Hall H, Klimov A, Fukuda K. (2000) Effectiveness and cost-benefit of influenza vaccination of healthy working adults. Journal of the American Medical Association 284: 1655–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DS, Rumley MH. (1997) Cost-effectiveness of the influenza vaccine in a healthy, working-age population. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 39(5): 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Darling C, Hampson A, Downs K, Tasset-Tisseau (2003) Influenza vaccinated in an occupational setting: Effectiveness and cost-benefit study. Journal of Occupation Health and Safety, Australia and New Zealand 19(2): 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Danon L, House TA, Read JM, Keeling MJ. (2012). Social encounter networks: Collective properties and disease transmission. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 9(76): 2826–2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dille JH. (1999) A worksite influenza immunization program. Impact on lost work days, health care utilization, and health care spending. Official Journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses 47(7): 301–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Ferroni E, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C. (2014) Vaccines for preventing influenza in health adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 13(3): CD001269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago R, Miller K. (2010) Sick at Work: Infected employees in the workplace during the H1N1 pandemic. Available at: http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/sick-at-work-infected-employees-in-the-workplace-during-the-h1n1-pandemic (accessed 23 March 2016).

- Economic and social impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza (2006) Vaccine 24(44–46): 6776–6778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Tomba G, de Blasio B. (2016) Influenza in workplaces: Transmission, workers’ adherence to sick leave advice and European sick leave recommendations. European Journal of Public Health 26(3): 478–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney A, North F, Head J, Canner R, Marmot M. (1998) Socioeconomic and sex differentials in reason for sickness absence from the Whitehall II Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(2): 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrick AM, Jinnett K, Parry T. (2011) Synergies at Work: Realizing the Full Value of Health Investments. San Francisco, CA: Integrated Benefits Institute/Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. [Google Scholar]

- Fendrick AM, Monto AS, Nightengale B, Sarnes M. (2003) The economic burden of non-influenza-related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine 163(4): 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W. (2004) Health absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 46(4): 398–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond B, Ali Y, Fendler E, Dolan M, Donovan S. (2000) Effect of hand sanitizer use on elementary school absenteeism. American Journal of Infection Control 28(5): 340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CD, Andersen JH. (2008) Going ill to work—What personal circumstances, attitudes and work-related factors are associated with sickness presenteeism? Social Science and Medicine 67(6): 956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S, Zimmerman P, van de, Mortel T. (2017) Assessing workplace infectious illness management in Australian workplaces. Infection, Disease and Health 22(1): 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner N-O, Hübner C, Wodny M, Kampf G, Kramer A. (2010) Effectiveness of alcohol-based hand disinfectants in a public administration: Impact on health and work performance related to acute respiratory symptoms and diarrhoea. BMC Infectious Disease 10: 250–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Al-Ansary LA, Ferroni E, Thorning S, Thomas RE. (2010) Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 17(2): CD004876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson T, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C, Demicheli V, Ferroni E. (2012) Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 15(8): CD004879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns G. (2010) Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31(4): 519–542. [Google Scholar]

- Keech M, Scott AJ, Ryan PJ. (1998) The impact of influenza and influenza-like illness on productivity and healthcare resource utilization in a working population. Occupational Medicine 48(2): 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki M, Head J, Ferrie JE, Hemingway H, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG. (2005) Working while ill as a risk factor for serious coronary events: The Whitehall II study. American Journal of Public Health 95(1): 98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Grefenstette JJ, Galloway D, Albert SM, Burke DS. (2013) Policies to reduce influenza in the workplace: Impact assessments using an agent-based model. American Journal of Public Health 103(8): 1406–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton L, Williams M, Aubery D, Parker SH. (1996) Sickness absence following a campaign of vaccination against influenza in the workplace. Occupational Medicine (London) 46(2): 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell V. (2005) Valuing Good Health: An Estimate of Costs and Savings for the Healthy Families Act. Available at: http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/valuing-good-health-an-estimate-of-costs-and-savings-for-the-healthy-families-act (accessed 25 January 2016).

- Lynd LD, Goeree R, O’Brien BJ. (2005) Antiviral agents for influenza: A comparison of cost-effectiveness data. PharmacoEconomics 23(11): 1083–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows E, Le Saux N. (2004) A systematic review of the effectiveness of antimicrobial rinse-free hand sanitizers for prevention of illness-related absenteeism in elementary school children. BMC Public Health 4: 50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millot JL, Aymard M, Bardol A. (2002) Reduced efficiency of influenza vaccine in prevention of influenza-like illness in working adults: a 7-month prospective survey in EDF Gaz de France employees, in Rhone-Alpes, 1996–1997. Occupational Medicine (London) 52(5): 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mixeu MA, Vespa GN, Forleo-Neto E, Toniolo-Neto J, Alves PM. (2002) Impact of influenza vaccination on civilian aircrew illness and absenteeism. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 73(9): 876–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohren DCL, Swaen GMH, Kant I, van Schayck CP, Galama JM. (2005) Fatigue and job stress as predictors for sickness absence. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine 12(1): 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, Bridges CB. (2007) The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: Measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 25(27): 5086–5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales A, Martinez MM, Tasset-Tisseau A, Rey E, Baron-Papillon F, Follet A. (2004) Costs and benefits of influenza vaccination and work productivity in a Colombian company from the employer’s perspective. Value Health 7(4): 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott PJ, Sisk BW, Arbogast JW, Ferrazzano-Yaussy C, Bondi CA, Sheehan JJ. (2007) Alcohol-based instant hand sanitizer use in military settings: A prospective cohort study of Army basic trainees. Military Medicine 172(11): 1170–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2010) Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare. Canberra, ACT: NHMRC. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol KL, D’Heilly SJ, Greenberg ME, Ehlinger E. (2009) Burden of influenza-like illness and effectiveness of influenza vaccination among working adults aged 50–64 years. Clinical Infectious Diseases 48(3): 292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol KL, Lind A, Margolis KL, Murdoch M, McFadden R, Hauge M, Magnan S, Drake M. (1995) The effectiveness of vaccination against influenza in healthy, working adults. New England Journal of Medicine 333: 889–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol KL, Mendelman PM, Mallon KP. (2003) Cost benefit of influenza vaccination in healthy, working adults: An economic analysis based on the results of a clinical trial of trivalent live attenuated influenza virus vaccine. Vaccine 21: 2207–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol KL, Mendelman PM, Mallon KP, Jackson LA, Gorse GJ, Belshe RB, Glezen WP, Wittes J. (1999) Effectiveness of live, attenuated intranasal influenza virus vaccine in healthy, working adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 282(2): 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen GW, Burris JM, Burlew MM, Steinberg ME, Patz NV, Stoltzfus JA, Mandel JH. (1998) Absenteeism among employees who participated in a workplace influenza immunization program. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 40: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LA, Rousculp MD, Johnston SS, Mahadevia PJ, Nichol KL. (2010) Effect of influenza-like illness and other wintertime respiratory illnesses on worker productivity: The child and household influenza-illness and employee function (CHIEF) study. Vaccine 28(31): 5049–5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston W, Jitnarin N, Haddock CK, Jahnke SA, Tuley BC. (2011) Obesity and injury-related absenteeism in a population-based firefighter cohort. Obesity 19(10): 2076–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt RJ, Pellowe CM, Wilson JA, Loveday HP, Harper PJ, Jones SR, MCDougall C, Wilcox MH. (2007) National evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. Journal of Hospital Infection 65(Suppl 1): S1–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JM, Eames KT, Edmunds WJ. (2008) Dynamic social networks and the implications for the spread of infectious disease. Journal of The Royal Social Interface 5(26): 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad AH, Usul MH, Zakaria D, Ismaili R, Tasset-Tisseau A, Baron-Papillon F, Follet A. (2006) Workplace vaccination against influenza in Malaysia: Does the employer benefit? Journal of Occupation Health 48: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro N, Tasset-Tisseau A, Nicoloyanis N, Armoni J. (2004) Nine years of influenza vaccination in an Argentinean company: Costs and benefits for the employer. International Congress Series 1263: 590–4. [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen-Kopra C, Haapakoski J, Peltola PA, Ziegler T, Korpela T, Anttila P, Amiryousefi A, Huovinen P, Huvinen M, Noronen H, Riikkala P, Roivainen M, Ruutu P, Teirila J, Vartiainen E, Hovi T. (2012) Hand washing with soap and water together with behavioural recommendations prevents infections in common work environment: An open cluster-randomized trial. Trials 13: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanzer DL, Zheng H, Gilmore J. (2011) Statistical estimates of absenteeism attributable to seasonal and pandemic influenza from the Canadian Labour Force Survey. BMC Infectious Diseases 11: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skagan K, Collins AM. (2016) The consequences of sickness presenteeism on health and wellbeing over time: A systematic review. Social Science Medicine 161: 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AP, Brice C, Leach A, Tiley M, Williamson S. (2004) Effects of upper respiratory tract illnesses in a working population. Ergonomics 47(4): 363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Thomas M, Whitney H. (2000) Effects of upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance over the working day. Ergonomics 43(6): 752–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurzem CW. (1996) Influenza vaccination: impact on certificated school staff absenteeism. PhD thesis. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman-Smith M, DuBois CLZ, Grey S, Kingsbury DM, Shakya S, Scofield J, Slenkovich K. (2015) Outcomes of a pilot hand hygiene randomized cluster trial to reduce communicable infections among US office-based employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 57(4): 374–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y, Zhou F, Kim IK. (2014) The burden of influenza-like illness in the US workforce. Occupational Medicine 64: 341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhari M, Möttönen M. (1999) An open randomised controlled trial of infection prevention in child day-care centres. Paediatric Infectious Disease Journal 18(8): 672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Camp RO, Ortega HJ., Jr (2007) Hand sanitizer and rates of acute illness in military aviation personnel. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 70: 140–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel T. (2008) Is hand hygiene linked to health benefits in the community in developed countries? In: Anderson PL, Lachan JP. (eds) Hygiene and Its Role in Health. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp. 181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore R, Knafl K. (2005) The integrative review: An updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52(5): 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014) Influenza (seasonal). Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/ (accessed 28 April 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_1 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_2 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_3 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention

Supplemental material, JIP772184_Supplementary_Appendix_4 for Infectious illness prevention and control methods and their effectiveness in non-health workplaces: an integrated literature review by Stephanie Hansen, Peta-Anne Zimmerman and Thea F van de Mortel in Journal of Infection Prevention