Abstract

This narrative review highlights key issues in men’s mental health and identifies approaches to research, policy and practice that respond to men’s styles of coping. Issues discussed are: 1) the high incidence of male suicide (80% of suicide deaths in Canada, with a peak in the mid-50 s age group) accompanied by low public awareness; 2) the perplexing nature of male depression, manifesting in forms that are poorly recognised by current diagnostic approaches and thus poorly treated; 3) the risky use of alcohol among men, again common and taking a huge toll on mental and physical health; 4) the characteristic ways in which men manage psychological suffering, the coping strengths to be recognised, and the gaps to be addressed; 5) the underutilization of mental health services by men, and the implication for clinical outcomes; and 6) male-specific approaches to service provision designed to improve men’s accessing of care, with an emphasis on Canadian programs. The main conclusion is that a high proportion of men in Western society have acquired psychological coping strategies that are often dysfunctional. There is a need for men to learn more adaptive coping approaches long before they reach a crisis point. Recommendations are made to address men’s mental health through: healthcare policy that facilitates access; research on tailoring interventions to men; population-level initiatives to improve the capacity of men to cope with psychological distress; and clinical practice that is sensitive to the expression of mental health problems in men and that responds in a relevant manner.

Keywords: Barriers to treatment, Common mental disorders, Depressive disorders, emental health, Gender, Healthcare utilization

Abstract

Enjeux importants de la santé mentale des hommes Cet examen narratif présente les principaux enjeux de la santé mentale des hommes et énumère les approches de la recherche, des politiques et de la pratique qui répondent aux styles d’adaptation des hommes. Les enjeux discutés sont : 1. l’incidence élevée de façon inquiétante du suicide masculin (80 % des décès par suicide au Canada, avec une pointe dans le groupe d’âge de mi-cinquantaine) accompagnée d’une faible sensibilisation du public; 2. la nature déroutante de la dépression masculine, qui se manifeste sous des formes mal reconnues par les approches diagnostiques actuelles et qui est donc mal traitée; 3. l’usage risqué de l’alcool par les hommes, encore une fois répandu de façon inquiétante, qui a de très lourdes répercussions sur la santé mentale et physique; 4. les façons caractéristiques des hommes de composer avec la souffrance psychologique, les aptitudes d’adaptation à reconnaître et les lacunes à aborder; 5. la sous-utilisation par les hommes des services de santé mentale et l’implication pour les résultats cliniques; et 6. les approches typiquement masculines de la prestation de services conçue pour améliorer l’accès aux soins pour les hommes, en mettant l’accent sur les programmes canadiens. La principale conclusion est qu’une forte proportion d’hommes dans la société occidentale ont acquis des stratégies d’adaptation qui sont souvent dysfonctionnelles. Il y a un besoin pour les hommes d’apprendre plus d’approches d’adaptation, bien avant d’atteindre le point d’une crise. Des recommandations qui abordent la santé mentale des hommes se trouvent dans : les politiques de santé qui facilitent l’accès; la recherche sur la personnalisation des interventions pour les hommes; les initiatives dans la population pour renforcer la capacité des hommes de s’adapter à la détresse psychologique; et la pratique clinique qui est sensible à l’expression des problèmes de santé mentale chez les hommes et qui y répond de façon pertinente.

Introduction

There is increasing public awareness of the importance of a gendered perspective on the mental health of Canadian men. This perspective considers effective intervention approaches, barriers to accessing appropriate care and psychological coping issues. It has been observed that men’s mental health issues have been ‘hidden in plain sight’. For example, even though it is well known that most suicide deaths are males, there has historically been a lack of attention to this dramatic gender disparity, whether in health research, policy, or care delivery. The research literature on men’s mental health, policy addressing this area, and psychological care specifically targeting men are all in early stages of development.

The aim of this review is to highlight some of the key issues in men’s mental health. The time is right to implement new approaches to research, policy and practice that respond to men’s styles of coping, vulnerability and psychological suffering. We are past the point where mere calls to action will suffice.

Critical Issues

Male Suicide

Suicide in men has been described by a leading researcher as a ‘silent epidemic’. 1 It is ‘silent’ because there is low public awareness regarding the magnitude of this problem, with surprisingly little research and few preventive efforts specifically targeting male suicide. Furthermore, men are reluctant to seek help for suicidality. It is ‘epidemic’ because of the high incidence and because it is a major contributor to men’s mortality: between the ages of 15 and 44 y, suicide is among the top 3 sources of men’s mortality.2 Across all countries reporting these data (except China and India), the male suicide rate that is 3- to 7.5-times that of women.3 In Canada, the male suicide rate is about 3 times that of women.4

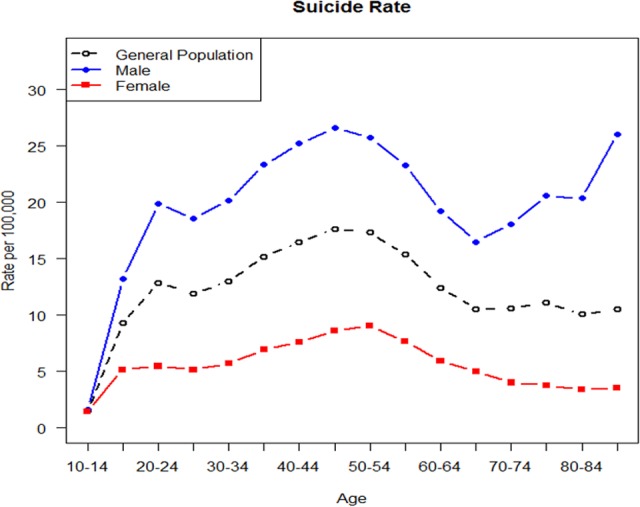

Figure 1 charts the age- and gender-specific incidence of suicide in Canada, based on data from 2000 to 2011. The chart shows 2 patterns:

The male suicide rate increases fairly steadily with age, peaking in the late 40s, then falling significantly and rising again in the 80s.

Male rates of suicide are greater than female rates at all ages and substantially greater across most of the lifespan.

Figure 1.

Average Age-Specific Suicide Rates Ages 10+ from 2000 to 2011. (Reproduced with permission from Jones W, Goldner EM, Butler A, McEwan K. Informing the future: mental health indicators for Canada technical report. Mental Health Commission of Canada RFP No. MHCC-DATA-2013-2014-02; 2015. Page 314.)

The peak in suicide rate among Canadian men in their 40s and 50s is surprising in light of past data showing a peak of suicide in younger age groups.5,6 However, a change in this suicide pattern seems to be underway. It is apparent that our knowledge of men’s suicide is lagging behind changes in the age-specific incidence of this cause of death.7 Until we understand the underlying reasons for this relative increase in men’s suicide rates in middle age, including potential cohort effects, we will not be able to implement effective preventive action.

To address male suicide, it will be important to understand how suicidality manifests in men and how it can be detected at an early stage. A recent review found that signs indicative of increased suicidal risk in men include ‘desperation and frustration in the face of unsolvable problems, helplessness, worthlessness, statements of suicidal intent’.8 However, the reviewers highlight the uncertainty regarding the sensitivity and specificity of these signs in identifying men’s suicidal risk and call for prospective research to identify signs of imminent risk of suicidal ideation, attempt, or death in men. A recent longitudinal study of 13,884 men found that one aspect of Western role norms of masculinity may contribute to men’s suicide ideation, in that men who strongly identified as ‘self-reliant’ had 34% greater odds of reporting thoughts of suicide.9 However, suicidal thinking alone is not a sufficient predictor of an imminent attempt.10 An intriguing qualitative study examined factors that interrupt suicide attempts in men, finding that ‘suicidal ideation may be reduced through provision of practical help to manage crises, and helping men to focus on obligations and their role within families’.11 Further, in a survey of men who had previously made a suicide attempt, 67% reported ‘thinking about the consequences for family’ helped prevent future attempts.12

Follow-up analyses highlight some tensions between suicidal men and their support systems that interfere with effective suicide prevention.13 For example, it is difficult to identify which changes in behaviour signify imminent risk of an attempt v. normal fluctuations in mood; or difficulty in monitoring signs of risk while still affording at-risk men privacy and autonomy. Though recent work suggests that men are more likely than women to develop an ‘acquired capability’ for suicide through greater insensitivity to pain and reduced fear of death,14 there is still considerable debate over the role of biology15 v. social factors (e.g., men tend to have a higher occupational exposure to pain-habituating experiences16).

Male Depression

Epidemiological research shows that the incidence of unipolar depression in men is half that for women.17 Three main explanations have been proffered. First, men are simply less likely to experience depression, for unclear reasons. Second, men are reluctant to acknowledge depressive symptoms due to aspects of male socialization.18 Third, men experience depression in a specific way, with different symptoms, such that the standard operational criteria for depression (which typically emphasise internalizing symptoms such as sadness and worry) are not valid in a male population.19,20 This latter explanation is built upon the concept of ‘male depressive syndrome’, where externalizing symptoms (e.g., anger, alcohol misuse, risk-taking) are considered indicative of men’s depression yet not diagnostically recognised as such.21,22 A recent systematic review compared the patterns of symptoms in men and women diagnosed with unipolar depression, finding relatively minor differences. They found that effect sizes for these symptoms were small except for risk taking and poor impulse control, indicating that differences between genders on most symptoms may have only minor clinical relevance for the assessment and treatment of depression.23 However, if men’s depression is qualitatively different, many men will not be ‘diagnosed’ as depressed and thus will be absent from the literature. There is some evidence that men describe depression using language (e.g. ‘stressed’, ‘angry, ‘tired’) that does not concord with existing clinical criteria, or endorse different warning signs of depression (e.g., being ‘irritable’, ‘on auto-pilot’, and ‘more aggressive towards others’).12 It is notable that the concept of a male-version depression raises the question of depression’s ontological status—we lose the epistemic shelter of operational definition (as in the DSM, where depression is that which meets the criteria) and must seek a theoretical definition of depression encompassing different presentations.

Men and Substance Use

Alcohol has the greatest impact upon men’s mental health across all substance use. The overuse of alcohol to cope with psychological distress, resulting in significant mental health impact and dependence, is common in men. Men are 2- to 3-times more likely than women to have a serious alcohol use problem.24,25,26 In a 2012 study of mental health and substance use disorders in Canada, it was found that ‘males had higher rates of substance use disorders in the past 12 months…6.4% of males and 2.5% of females reported symptoms consistent with substance use disorder’.27

Alcohol use is a risk factor for a number of serious disorders and sources of mortality.28 As one might expect from their relatively high rate of use, men suffer disproportionately from the health impacts of alcohol: data from 2004 show the rate of global deaths attributable to alcohol use as almost 6-times higher for men (6.3%) than for women (1.1%).29 It is worth noting that alcohol dependence is a strong contributor to suicidality, suggesting a partial explanation for the association between male gender and suicide mortality.30

Regarding the mitigation of alcohol-related risk in men, a systematic review of long-term outcome in alcohol dependence found that men show strikingly worse outcomes than do women.31 Yet, another review found that effort in the primary care setting to reduce levels of problem drinking is equally efficacious for men and women.32

An intriguing development is the potential role of cannabis as a substitute for alcohol in individuals who have been using alcohol in a risky manner.33 Notably, in US states that have legalised medical cannabis, decreases in deaths due to motor vehicle accidents and suicide have been observed; it has been suggested that these decreases may be related to substitution of alcohol by cannabis in young men.34,35 There is a need for research in this area.

Opioid misuse (especially fentanyl) has come into sharp focus due to the staggering number of associated overdose deaths. Despite intense public concern, only recently has attention been drawn to the preponderance of men in these deaths: for example, a review of fentanyl overdose deaths in British Columbia between 2012 and 2017 found that 82% involved men.36 Although there has been some research on gender differences in opioid use,37,38 little is known about the reasons for this substantial disparity in overdose deaths. We speculate that the same social influences and coping strategies leading men to overuse alcohol foster other forms of substance misuse as well.

How Men Cope with Psychological Distress

Recent research has studied the ways in which men cope with psychological suffering. Recent reviews have attributed the use of negative coping styles to the tendency of some men to adhere rigidly to certain stereotyped features of masculinity: misuse of alcohol and drugs to numb distress; concealing and ignoring negative emotions; engaging in risky behaviours; or valuing self-reliance and autonomy over professional care.39,40 Such approaches can increase the risk of suicide, if used in conjunction with social isolation and withdrawal from relationships.11

Some men report attempts to redefine notions of masculine coping; for example, where help-seeking allows for the maintenance of traditional roles such as providing for the family.41 A research group in Australia has been examining positive coping strategies used by men: far from relying only on negative coping strategies, many men reported enacting various prevention and management strategies for mood maintenance.39,42 Interestingly, these positive strategies fell along a continuum – some men were more comfortable with ‘typically masculine’ approaches (e.g. problem solving, achievements, structured plans, goal-setting) while others were open to using less ‘masculine’ strategies (e.g. acceptance of vulnerability, talking openly about problems, seeking help). Crucially, some men described only becoming open to such strategies after significant periods of distress.

Men’s Use of Mental Health Care

A considerable body of research has identified a notably lower utilization of mental health care by men.43 One might assume that this usage pattern reflects a lower rate of common mental health conditions such as depression, but the available research data tends to point rather to men’s reluctance to access mental health care; i.e., a pervasive disinclination to seek help in dealing with psychological distress, whether help from the health system, family members, or friends.44,45 Indeed, men are often unwilling to express or acknowledge psychological suffering.46 A recent review found that the degree of individual adherence to masculine role norms negatively impacts help-seeking, such that treatment is delayed until internal resources are depleted or a crisis-point reached.47 Barriers to help-seeking, such as a need for control, self-reliance or tendency to minimize symptoms, are more likely in the context of long-standing depression in men.48 A recent meta-analysis reported a stronger link between conforming to masculine norms and reduced help-seeking than with mental health outcomes per se.49 Interestingly, Canadian research found that men were unlikely to disclose distress to their doctors, regardless of measures of masculinity or symptom severity.50

Taken together, the research implies a knock-on effect where men do not perceive the need for care, immediate support systems do not identify male-specific warning signs, diagnostic criteria do not detect men with mental health problems, and men delay treatment until problems are too severe to ignore. Efforts have been made to address this poor ‘accessing of care’ (v. ‘access to care’) and there are indicators of change.51 For example, in Australia, the proportion of men with mental health problems who used appropriate services has increased from 32% in 2006–2007, to 40% in 2011–2012.52 However, there is substantial room for improvement.

Male-Specific Mental Health Services

A recently released policy review, ‘Keeping It Real’, emphasizes the importance of implementing novel programs that reach out to men, and designing care approaches that enhance coping.53 Promising examples of online interventions to enhance psychological coping include the MoodGym program; however, such online interventions show lower uptake and adherence in men.54,55,56 A review noted a ‘high drop-out rate amongst males in particular and certain programmes such as MoodGym appear insufficiently engaging to adult men’.55 Nonetheless, we would argue that given existing challenges to men’s timely accessing of appropriate care, development of e-health interventions is still a promising avenue, particularly where such programs are designed with men’s input.

Male-specific programs include:

The Australian ‘Well@Work’ program, which aims to improve workplace mental health in male-dominated workforces (e.g., police, fire, and emergency services);57

An ambitious mental health prevention and promotion program targeting adolescent boys via community-based sports clubs, funded by the Movember Foundation;58

A Canadian adaptation of the Australian Men’s Shed program, which focuses on the mental health of older men;59,60

HeadsUpGuys, a website where men can access psychoeducation regarding depressive symptoms among men, practical tips for preventing and dealing with depression, how to access professional services, and videos of men who have overcome depression;61

BroMatters, which provides psychoeducation about stress, depression, and alcohol use, along with self-help in the form of CBT, mindfulness relaxation programs and strategies for workplace stress.62

DUDES Club, a ground-breaking program primarily targeting the health and well-being of indigenous men in Vancouver, BC’s Downtown Eastside—a group of men facing high risk of addiction, poverty, and homelessness.63 The goal of DUDES Club is to promote health literacy and build a sense of ‘brotherhood’. It integrates traditional indigenous medicine and teachings and provides access to healthcare professionals who facilitate interactive ‘health discussions’.

Although several of these programs have received formative evaluation, it must be emphasised that none has been proven effective by controlled research trials. They are promising but unproven.

Conclusions

The central conclusion we derive from the literature on men’s mental health is this: a high proportion of men in Western society have acquired psychological coping strategies that are often dysfunctional and leave them vulnerable to a number of negative physical or psychological outcomes. This acquisition is not necessarily inherent to being male, but rather a product of various degrees of socialization to Western role norms. The problematic coping strategies include:

Failing to obtain appropriate support from friends, family, or healthcare providers;

Overusing alcohol to lessen emotional suffering

Denying suffering, ‘sucking it up’

Isolation, or reducing social connectedness in times of distress

Each of these coping strategies will, in situations, be appropriate and adaptive; for example, indifference to suffering in emergency situations where certain tasks must be accomplished. Likewise, brief periods of isolation can relieve stress. However, using these strategies excessively or rigidly leaves men vulnerable to a wide range of negative consequences and less able to access the health buffering effects of diverse social support networks.64 There is a need for men to learn adaptive coping approaches long before they reach a crisis point.

Recommendations

Policy

Healthcare policy should mandate that Health Services to men be delivered in a way that is appropriate and acceptable to those men in need. Male-focused programs appear to hold considerable potential for improving our management of men’s mental health. However, such programs have thus far reached only a small proportion of the male population, and it is unclear how scalable they are to the male population vulnerable to mental health conditions and psychological suffering.

Further, though many countries have mental health strategies that acknowledge gender differences, very few articulate strategies aimed at men. Future policy development should identify men as a vulnerable population and articulate specific strategies to address the known factors that increase mental health risk among men. A useful resource for policy development is the Keeping It Real report, which focuses on policy development aimed at young men’s mental health.53

Research

The Canadian research agenda should make men’s mental health a priority, including outcome research to determine how existing treatment methods could be tailored to a male population and how men can be encouraged to increase appropriate use of mental health services.65 Furthermore, suicide-prevention research, which has focused on teens and young adults, should prioritize middle-aged men, as they are the most vulnerable group.

Population Health Intervention

Population-level initiatives should be implemented to enhance the capacity of Canadian men to cope with psychological distress and thus help prevent the negative consequences of poorly managed suffering. Such an initiative would be based on evidence about positive coping strategies, tailored knowledge translation, and social marketing. One approach would involve community education and prevention campaigns that engage with traditional notions of masculinity and seek to reframe men’s vulnerability to mental health problems, men’s typical responses to such vulnerability, and the act of help-seeking as brave and a ‘masculine’ thing to do.66 Another would involve novel delivery of treatment and skills development to larger population groups, whether through new technology or diverse settings. Continued development and evaluation of online interventions designed to engage men is a promising approach.

Clinical Practice

This review points to several important aspects of clinical work with male patients. First, men are more prone to anger and interpersonal aggression, a coping pattern with substantial negative impact on quality of life and relationships. There is a need for enhanced clinical focus on identifying and modifying anger coping skills in men. Second, identifying high-risk use of alcohol is a key issue in the clinical care of men. High-risk use is, of course, far more common than diagnosable alcohol dependence (which requires intensive treatment). Controlled drinking or supported self-care interventions are appropriate for most men overusing alcohol.67,68 Third, the clinician must be sensitive to suicidality in men, even where the patient dismisses his own emotional suffering and presents relationship or occupational crises in a calm and ‘rational’ manner.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. BBC NEWS, UK. The silent epidemic of male suicide. 2008. February 4 London (UK): BBC News; [Cited 2017 July 31] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/7219232.stm. [Google Scholar]

- 2. British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency, Ministry of Health Planning Selected Vital Statistics and Health Status Indicators: Annual Report 2002. Victoria (BC): Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones W. Background Epidemiological Review of Selected Conditions. Burnaby (BC): Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shah A. The relationship between suicide rates and age: an analysis of multinational data from the World Health Organization. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(6):1141–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicidologi. 2002;7(2):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu G, Wilcox HC, Wissow L, et al. Midlife suicide: an increasing problem in US Whites, 1999-2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(6):589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hunt T, Wilson CJ, Caputi P, et al. Signs of current suicidality in men: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017. [Cited 2017 July 31];12(3):10 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5371342/doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pirkis J, Spittal MJ, Keogh L, et al. Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(3):319–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Player MJ, Proudfoot J, Fogarty A, et al. What interrupts suicide attempts in men: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shand FL, Proudfoot J, Player MJ, et al. What might interrupt men’s suicide? Results from an online survey of men. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fogarty AS, Spurrier M, Player MJ, et al. Tensions in perspectives on suicide prevention between men who have attempted suicide and their support networks: Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Health Expect. Forthcoming 2017;21(1):261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Witte TK, Gordon KH, Smith PN, et al. Stoicism and sensation seeking: male vulnerabilities for the acquired capability for suicide. J Res Pers. 2012;46(4):384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deshpande G, Baxi M, Witte T, et al. A neural basis for the acquired capability for suicide. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bryan CJ, Cukrowicz KC, West CL, et al. Combat experience and the acquired capability for suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(10):1044–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, et al. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord. 1993;29(2):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aneshensel CS, Estrada AL, Hansell MJ, et al. Social psychological aspects of reporting behavior: lifetime depressive episode reports. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28(3):232–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rutz W, von Knorring L, Pihlgren H, et al. Prevention of male suicides: lessons from Gotland study. Lancet. 1995;345(8948):524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Möller-Leimkuühler AM. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Addis ME. Gender and depression in men. Clin Psychol Sci Pr. 2008;15(3):153–168. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rice SM, Aucote HM, Parker AG, et al. Men’s perceived barriers to help seeking for depression: longitudinal findings relative to symptom onset and duration. J Health Psychol. 2015;22(5):529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cavanagh A, Wilson CJ, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Differences in the expression of symptoms in men versus women with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):29–38, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, et al. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1487–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Eighth Special Report to the US Congress on Alcohol and Health. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eaton WW, Kramer M, Anthony JC, et al. The incidence of specific DIS/DSM-III mental disorders: data from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1989;79:163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. CDC - Fact Sheets - Alcohol Use and Health - Alcohol. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. July 25 [Cited 2017 July 31]. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rehm J, Mathers CF, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moreira CA, Marinho M, Oliveira J, et al. Suicide attempts and alcohol use disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:521.25725594 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bravo F, Gual A, Lligoña A, et al. Gender differences in the long-term outcome of alcohol dependence treatments: an analysis of twenty-year prospective follow up. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(4):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ballesteros J, González-Pinto A, Querejeta I, et al. Brief interventions for hazardous drinkers delivered in primary care are equally effective in men and women. Addiction. 2004;99(1):103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lucas P, Walsh Z, Crosby K, et al. Substituting cannabis for prescription drugs, alcohol and other substances among medical cannabis patients: the impact of contextual factors. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35(3):326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI. Medical marijuana laws, traffic fatalities, and alcohol consumption. J Law Econ. 2013;56(2):333–369. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anderson DM, Rees DI. The legalization of recreational marijuana: how likely is the worst-case scenario? J Policy Anal Manage. 2014;33(1):221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. British Columbia Coroners Service. Fentanyl-Detected Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths: January 1, 2012 to April 30, 2017. Burnaby (BC): Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, Office of the Chief Coroner; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Back SE, Payne RL, Simpson AN, et al. Gender and prescription opioids: findings from the national survey on drug use and health. Addict Behav. 2010;35(11):1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jamison RN, Butler SF, Edwards RR, et al. Gender differences in risk factors for aberrant prescription opioid use. J Pain. 2010;11(4):312–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Whittle EL, Fogarty AS, Tugendrajch S, et al. Men, depression, and coping: are we on the right path? Psychol Men Masc. 2015;16(4):426–438. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spendelow JS. Men’s self-reported coping strategies for depression: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Psychol Men Masc. 2015;16(4):439–447. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roy P, Tremblay G, Robertson S. Help-seeking among male farmers: connecting masculinities and mental health. Sociologia Ruralis. 2014;54(4):460–476. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Proudfoot J, Fogarty AS, McTigue I, et al. Positive strategies men regularly use to prevent and manage depression: a national survey of Australian men. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kessler RC, Brown RL, Broman CL. Sex differences in psychiatric help-seeking: evidence from four large-scale surveys. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(1):49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moller-Leimkuhler AM. Barriers to help seeking by men: a review of socio-cultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1–3):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Doherty DT, Kartalova-O’Doherty Y. Gender and self-reported mental health problems: predictors of help seeking from a general practitioner. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(1):213–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Good GE, Mintz LB. Gender role conflict and depression in college men: evidence for compounded risk. J Couns Dev. 1990;69(1):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Seidler ZE, Dawes AJ, Rice SM, et al. The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;49:106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rice SM, Fallon BJ, Aucote HM, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the male depression risk scale: furthering the assessment of depression in men. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wong YJ, Ho MR, Wang SY, et al. Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(1):80–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wide J, Mok H, McKenna M, et al. Effect of gender socialization on the presentation of depression among men: a pilot study. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(2):e74–e78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whiteford HA, Buckingham WJ, Harris MG, et al. Estimating treatment rates for mental disorders in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(1):80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harris MG, Diminic S, Reavley N, et al. Males’ mental health disadvantage: an estimation of gender-specific changes in service utilisation for mental and substance use disorders in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(9):821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Baker D, Rice S. Keeping It Real: Reimagining Mental Health Care for All Young Men. Melbourne (AUS): Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Twomey C, O’Reilly G, Byrne M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the computerized CBT programme, MoodGYM, for public mental health service users waiting for interventions. Br J Clin Psychol. 2014;53:433–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Robertson S, White A, Gough B, et al. Promoting Mental Health and Wellbeing with Men and Boys: What Works? Leeds (UK): Centre for Men’s Health, Leeds Beckett University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fogarty AS, Proudfoot J, Whittle EL, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a brief web and mobile phone intervention for men with depression: men’s positive coping strategies and associated depression, resilience, and work and social functioning. JMIR Ment Health. 2017;4(3):e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Deady M, Peters D, Lang H, et al. Designing smartphone mental health applications for emergency service workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2017;67(6):425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Movember Australia. Report Cards. Melbourne (AUS): Movember Foundation; c2017 [Cited 2017 July 31] https://au.movember.com/report-cards/view/id/3276/a-national-and-sustainable-sports-based-intervention-to-promote-mental-health-and-reduce-the-risk-of-mental-health-problems-in-australian-adolescent-males [Google Scholar]

- 59. Men’s Sheds Canada. Winnipeg (MB): Canadian Men’s Sheds Association; [Cited 2017 September 18] http://menssheds.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nurmi MA, MacKenzie CS, Roger K, et al. Older men’s perceptions of the need for and access to male-focused community programmes such as Men’s Sheds. Ageing Soc. 2016. [Cited 2017 September 18]. doi:10.1017/S0144686X16001331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. HeadUpGuys | Manage & Prevent Depression in Men. Vancouver (BC): HeadsUpGuys; [Cited 2017 July 31] https://headsupguys.org. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang J, Patten SB, Lam RW, et al. The effects of an e-mental health program and job coaching on the risk of major depression and productivity in Canadian male workers: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(4):e218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gross PA, Efimoff I, Lyana P, et al. The DUDES Club: a brotherhood for men’s health. Can Fam Phys. 2016;62: e311–e318. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Smith DT, Mouzon DM, Elliott M. Reviewing the assumptions about men’s mental health. Am J Mens Health. 2016. [Cited 2017 July 31]. doi: 10.1177/1557988316630953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Värnik A, Kõlves K, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, et al. Suicide methods in Europe: a gender-specific analysis of countries participating in the “European Alliance Against Depression”. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(6):545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Man Therapy uses a caricature “Dr. Brian Ironwood” to talk about men’s problems, with some evidence of impact. Media Releases. Hawthorn (AUS): Beyond Blue Ltd; c2016 [Cited 2017 July 31] http://www.beyondblue.org.au/media/media-releases/media-releases/almost-half-of-aussie-men-have-listened-to-dr-brian-ironwood-s-mental-health-messages. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ettner SL, Xu H, Duru OK, et al. The effect of an educational intervention on alcohol consumption, at-risk drinking, and health care utilization in older adults: The Project SHARE study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(3):447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Brief Intervention for Hazardous and Harmful Drinking: A Manual for Use in Primary Care. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]