Abstract

Numerous scholars have stated that there is a silent crisis in men’s mental health. In this article, we aim to provide an overview of core issues in the field of men’s mental health, including a discussion of key social determinants as well as implications for mental health services. Firstly, we review the basic epidemiology of mental disorders with a high incidence and prevalence in men, including suicide and substance use disorder. Secondly, we examine controversies around the low reported rates of depression in men, discussing possible measurement and reporting biases. Thirdly, we explore common risk factors and social determinants that may explain higher rates of certain mental health outcomes in men. This includes a discussion of 1) occupational and employment issues; 2) family issues and divorce; 3) adverse childhood experience; and 4) other life transitions, notably parenthood. Fourthly, we document and analyze low rates of mental health service utilization in men. This includes a consideration of the role of dominant notions of masculinity (such as stubbornness and self-reliance) in deterring service utilization. Fifthly, we note that some discourse on the role of masculinity contains much “victim blaming,” often adopting a reproachful deficit-based model. We argue that this can deflect attention away from social determinants as well as issues within the mental health system, such as claims that it is “feminized” and unresponsive to men’s needs. We conclude by calling for a multipronged public health–inspired approach to improve men’s mental health, involving concerted action at the individual, health services, and societal levels.

Keywords: men, gender, sex, men’s mental health, social determinants, mental health services, health service utilization

Abstract

Nombre de scientifiques ont déclaré qu’il y a une crise silencieuse de la santé mentale des hommes. Dans cet article, nous entendons offrir un aperçu des principaux enjeux du domaine de la santé mentale des hommes, y compris une discussion des déterminants sociaux clés, ainsi que des implications pour les services de santé mentale. Premièrement, nous examinons l’épidémiologie de base des troubles mentaux qui ont une incidence et une prévalence élevées chez les hommes, notamment le suicide et le trouble d’utilisation de substance. Deuxièmement, nous examinons les controverses au sujet des faibles taux déclarés de dépression chez les hommes, et discutons des mesures possibles et des biais de déclaration. Troisièmement, nous explorons les facteurs de risque communs et les déterminants sociaux qui peuvent expliquer les taux élevés de certains résultats de santé mentale chez les hommes. Cela comprend une discussion des (i) enjeux professionnels et d’emploi; (ii) questions familiales et de divorce; (iii) expériences indésirables dans l’enfance; et (iv) autres transitions de la vie, notamment la condition de parent. Quatrièmement, nous documentons et analysons les faibles taux d’utilisation des services de santé mentale chez les hommes. Cela inclut de prendre en considération le rôle des notions dominantes de masculinité (comme l’entêtement et la confiance en soi) pour éviter l’utilisation des services. Cinquièmement, nous notons qu’un certain discours sur le rôle de la masculinité contient beaucoup de « blâme jeté sur la victime » et adopte un modèle de reproche basé sur un déficit. Nous croyons que cela peut détourner l’attention des déterminants sociaux et des enjeux au sein du système de santé mentale, comme les allégations que le système est « féminisé » et qu’il ne répond pas aux besoins des hommes. Nous concluons en demandant une approche à branches multiples inspirée de la santé publique pour améliorer la santé mentale des hommes, mettant en jeu une action concertée au niveau individuel, ainsi qu’au niveau des services de santé et sociétal.

Researchers have long been interested in the impact of sex and gender on mental health. This interest has led to the development of two somewhat distinct but overlapping fields: the field of women’s mental health and the field of men’s mental health.

Interest in men’s mental health has increased dramatically in recent years due to a variety of factors. Firstly, studies in psychiatric epidemiology consistently indicate that men experience a significantly higher incidence and prevalence of certain mental health outcomes than women.1 Secondly, wider social science research suggests that broad socioeconomic change is leading to the marginalization of certain subgroups of men.2,3 Thirdly, activists and scholars from related domains including criminology, education, and psychology have successfully agitated for more attention to men’s (and boy’s) issues and well-being.4,5 All of these have legitimized the development of the field of men’s mental health, which now has common themes and focal points.

Indeed, interest in men’s mental health tends to revolve around a number of related issues, which will be discussed separately throughout this article. Firstly, we will discuss the basic epidemiology of mental disorders with a high incidence and prevalence in men. This will include a critical discussion of possible biases associated with low reported rates of depression. Secondly, we will explore common risk factors that may explain the higher rates of certain mental health outcomes in men. Thirdly, we will examine low rates of mental health service utilization in men and possible reasons to explain low service usage. A companion work in this issue examines specific clinical interventions for men in more detail,6 so this important area of men’s mental health is not emphasized in the present article.

Epidemiological Background

There are certain mental health outcomes that have a much higher prevalence in men. Indeed, recent North American research consistently indicates that men make up around 75% of suicide and 75% of substance use disorder (SUD) cases.7,8

The most recent detailed report from Statistics Canada indicates that there were 3890 suicides in 2009, of which 2989 were men (77%).7 Gender interacts with ethnicity to produce extremely high rates of suicide in some groups of men. Among the Canadian Inuit, for example, one recent study found that the ratio of suicide between men and women is 4.7:1 compared to 3.3:1 in the general Canadian population.8 These findings correspond with within-group suicide rates among ethnic minorities in the United States. Figures from a recent study by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that the ratio of suicide between African American men and women is 4.5:1 compared to 3.6:1 among the general US population.9

Likewise, men are much more likely to develop SUD than women. A 2012 Statistics Canada survey indicated that 6.4% of men met the threshold for at least 1 reported SUD compared to 2.5% of women.10 This survey indicates that men have higher rates of 1) non-cannabis drug abuse (0.9% men v. 0.5% women), 2) cannabis dependence and abuse (1.9% men v. 0.7% women), and 3) alcohol abuse or dependence (4.7% men v. 1.7% women). Recent statistics also show that 82% of deaths in the recent fentanyl crisis in British Columbia were men.11

Men also have significantly higher rates of mental disorders categorized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as “neurodevelopmental disorders.” According to a 2007 study, the male-to-female ratio of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis in Canada was almost 2.5:1.12 This ratio is similar to those found in other countries. Another study indicates that 14.2% of American boys were diagnosed with ADHD, compared to 6.4% of American girls, during the years 2013 to 2015.13 Boys are also significantly more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).14 Canadian research suggests that the male-to-female ratio for ASD ranges from 2.5:1 in Nova Scotia to 5.7:1 in Montreal.14 This is consistent with other research. In the United Kingdom; the prevalence of ASD in men is 1.8% compared to 0.2% for women.15

Men also have significantly higher rates of disruptive and impulse control disorders. Research from the United States indicates that the prevalence of intermittent explosive disorder is 9.3% for men compared to 5.6% for women.16 Further, a recent meta-analysis found that the global male-to-female ratio of oppositional defiant disorder is 1.6:1.17 For conduct disorder (CD), data from the Ontario Child Health Study indicate that the 6-month prevalence is 8.1% for boys compared to 2.7% for girls.18 A more recent study in the United States reported that the lifetime prevalence of CD is 12% for boys compared to 7.1% for girls.19

Common Mental Disorders: Real Differences or Artifactual Differences?

Psychiatric surveys routinely indicate that men have a significantly lower prevalence than women of common mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, at a ratio of approximately 1:2.20,21 Yet, some research indicates that these differences may be exaggerated due to measurement and reporting biases.

For example, research has found that men are much less likely to acknowledge and report possible symptoms of mood disorders such as depression and judge their symptoms as less severe in comparison to women. As Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus22 have suggested, men tend to blunt the reporting of possible symptoms of mood disorders perhaps because such symptoms are inconsistent with dominant notions of masculinity. Considering that most epidemiological measures of depression and anxiety rely on self-reported severity-based scales, these gendered differences in expression may influence both the reported incidence and prevalence.23,24

Furthermore, some researchers have gone so far as to suggest that there is a distinct and unrecognized “male depressive syndrome”25 that correlates with the older notion of “masked depression.”26 This is based on data suggesting that women tend to “act in” when faced with psychosocial suffering, while men “act out.” This “acting out” often involves high levels of alcohol and drug misuse, dangerous risk taking, poor impulse control, and increased anger and irritability. Again, these behaviours are more consistent with dominant notions of masculinity in comparison to crying or talking. Some have stated that these behaviours are “depressive equivalents,”27 masking an underlying sadness, loneliness, and alienation that reaches pathological levels in the afflicted men.

These differences in symptomatology present a number of challenges to psychiatric epidemiology. First, “acting out” symptoms are not included in standardized diagnostic or measurement criteria of depression and anxiety. This may result in inaccurately low prevalence rates as well as a preponderance of male false-negatives. This may help explain the comparatively low rates of common mental disorders and high rates of substance abuse and antisocial personality disorders in men. Second, this danger of misclassification may be compounded by issues of comorbidity, which are common between psychiatric conditions.28 Indeed, research has found that comorbidity between depression/anxiety and SUD is significantly more common in men than women.29 Third, in communities where alcohol and drug use are culturally prohibited, the disparity between men’s and women’s reporting of depressive symptoms narrows.30,31 In fact, studies that include “acting out” symptoms in depression measures suggest that men and women meet depression criteria in similar proportions.32

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that epidemiological and diagnostic measures are faulty is the large discrepancy between men’s low rates of depression and high rates of suicide. Depression is heavily implicated in suicide, underlying approximately half of completed suicides.33 Nevertheless, men kill themselves at a much higher proportion than women, despite experiencing significantly lower rates of depression. The hidden nature of men’s mental health symptoms, and the disconnect between low rates of diagnosis and high rates of suicide, has led some scholars to suggest a “silent crisis” in men’s mental health that is not being sufficiently addressed.34

Common Risk Factors: Employment and Occupational Issues

Epidemiological research on suicide, substance abuse, and depression in men indicates numerous common underlying risk factors. One of the key common risk factors is employment and occupational issues. Research indicates that unemployment can be a chronic stressor, while being made unemployed or redundant can be an acute stressor. Numerous studies have found that unemployment has a greater impact on the mental health of men in comparison to women.

For example, a 2009 meta-analysis of data from 26 predominantly Western countries between 1963 and 2004 found that the effect of unemployment on mental health was significantly stronger for men than for women.35 Likewise, a study using data from 1994 involving adults aged 25 to 64 years from the Catalonia region of Spain found that unemployment had nearly twice as severe an effect on the self-reported mental health of men than women.36

This difference between men and women may be because work has traditionally been the domain from which a man derives his self-identity, self-esteem, and self-worth. Work also provides status, income, and resources that can be used to support men and their families. As such, rupture and discontinuity in the work domain can lead to significant psychosocial stress as well as severe financial strain.

Indeed, one study found that low job security and conflict resulting from competing family and work responsibilities were predictive of depression. On the other hand, moderate levels of job strain were in fact found to be a protective factor against the development of depression in men,37 indicating the role of work in mental health promotion.

Indeed, uncertainty of employment, as well as levels of danger within the workplace, appears to be related to poor mental health. For example, recent research has found that male-dominated industries in economic precarity such as coal mining and commercial fishing have high rates of suicide. These industries have also seen the greatest increase in suicide over the past 30 years. In contrast, more gender-balanced growth industries such as white collar occupations have the lowest suicide rate and have had the greatest decrease in suicide over the past 30 years.38

These trends in men’s mental health are likely linked to macro-socioeconomic forces. The past decades have seen profound restructuring of Western economies with a transition from a manufacturing economy to a service-based knowledge economy. This has led to a decline in male-oriented industries with the closure of factories, mines, mills, and other manual industries that often gave men (especially rural less-educated men) a job for life and a meaningful place in their local communities.39 Indeed, research suggests that the highest male suicide rates in Canada are in rural areas of high unemployment.40,41

Indeed, statistics indicate that increasing proportions of men are taking on low-wage and low-skilled jobs. For the past 30 years, average male earnings have been steadily declining throughout many Western countries, while women’s earnings have been steadily increasing. Likewise, women under 40 years old are now significantly outearning their male peers, with many men struggling to find a place within the new economy.39

Trends in education, especially high school dropout, are likely implicated in these patterns. In 1990, 58.3% of high school dropouts were men. By 2005, this had increased to 63.7%.42 Male dropout rates in Canada were highest in the Province of Quebec. According to a report by the Action Group on Student Retention and Success in Quebec, 1 in 3 French Canadian boys drop out of high school before receiving a high school diploma.43 Incidentally, Quebec still has one of the highest suicide rates out of all the Canadian provinces.7,40,44 Young men also receive a significantly fewer number of university degrees. According to 2014 figures from Statistics Canada, men received 42% of both undergraduate and graduate degrees.45

Common Risk Factors: Family Issues and Divorce

Family is another life domain by which men garner significant purpose and meaning in life. Evidence suggests that divorce and romantic breakup are strong risk factors for mental illness and suicide.46 One study involving Canadian men and women aged 20 to 64 years found that the incidence of depression between 1994/1995 and 2004/2005 was nearly 4 times higher among recently separated or divorced individuals compared to those still in relationships.47 The same study also indicates that divorced men are roughly twice as likely to report depressive episodes in the 2 years following a divorce than divorced women, indicating that divorce tends to affect men worse than women.

The negative influence of divorce on men’s mental health has been attributed to numerous factors. A key factor is the loss of social support and emotional connectivity. For example, one study indicated that 19% of divorced or separated men reported a drop in social support compared to 11% for women.47 This is consistent with sociological research indicating that women tend to have larger circles of family and friends on whom they can rely after a divorce, whereas men tend to rely largely on their partner and nuclear family for emotional support.48 Thus, the loss of a partner can be particularly hard, as can the loss of any children deriving from the relationship.

Indeed, figures from the Department of Justice Canada show that around 80% of divorced fathers do not have custody of their children following a divorce,49 and only 15% of fathers will have their children live primarily with them.50 Evidence suggests that loss of custody and a negative experience in family court are some of the most stressful aspects of divorce for men and have been implicated in both substance abuse and suicide.51 Like employment loss, loss of custody can leave many men feeling bereft of purpose and meaning in life.

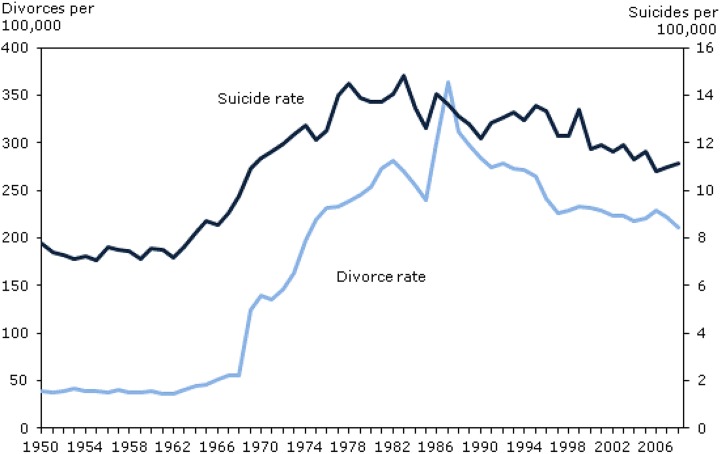

Indeed, rising divorce rates have been linked to rising suicide rates. During the 1950s, both divorce and suicide rates in Canada were fairly stable but began to rise in unison during the 1960s. Dramatic increases in both rates followed the passage of the Divorce Act in 1968 (Figure 1).7

Figure 1.

Association between divorce and suicide in Canada. Sources: Statistics Canada, Vital Statistics: Death Database; Statistics Canada, Vital Statistics: Divorce Database; and Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 051-0001 (Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories).

Common Risk Factors: Adverse Childhood Experience

Much evidence suggests that adverse childhood experiences can lead to short-term and long-term psychological and physical health consequences in men and women alike.52 Childhood abuse is common among boys and girls; however, some types of abuse are more prevalent in boys than girls (and vice versa). While sexual abuse tends to be more prevalent in girls, physical abuse tends to be higher in boys.53

Research indicates that boys and girls tend to respond differently to child abuse.54 Abused girls are more likely to display traditional mental health symptoms such as suicidal ideation and low self-esteem, often leading to self-harm and disordered eating. These symptoms can be identified through conventional mental health assessments, leading to targeted treatment and interventions. In contrast, abused boys are more likely to display a constellation of behaviours that may be less easy to classify psychiatrically, including delinquency, disruptive behaviours, school dropout, binge drinking, and risk taking.54 Such “externalizing” behaviours are often considered character issues rather than mental health issues. This means that negative thoughts and behaviours in men and boys are frequently labelled as social problems rather than health problems, leading to a punitive instead of a psychiatric response.

Common Risk Factors: Other Life Transitions

As previously stated, experiencing divorce and being made unemployed are two major risk factors for mental health problems in men. Many men find themselves ill equipped to adapt to a new reality following these transitions. Evidence suggests that other transitions can also increase the risk of mental illness in men and women. These include well-researched transitions such as bereavement and disability onset. However, some studies show that transitions that are generally considered positive and socially valued can also precipitate mental health issues. One such change is the transition to parenthood, which until recently has been underresearched in the case of fatherhood.

While a source of major joy for many men, the onset of fatherhood can also include radical life changes in areas such as work, sleep, financial stability, and social support. A growing number of research studies are indicating a mostly unrecognized syndrome known as paternal postpartum depression (PPD). Meta-analyses have found that PPD affects 10.4% of fathers.55 This is more than double the World Health Organization’s estimate of the global prevalence of depression in men (3.6%).56 PPD is especially prevalent in first-time fathers, and while it can be seen as early as the first trimester, it is highest in the 3- to 6-month postpartum period.57 Besides affecting the individual, PPD has been shown to exacerbate maternal postpartum depression55 and negatively affect the emotional, behavioural, and developmental outcomes of children.58,59 Despite representing a significant public health concern, little attention is paid to PPD in research or mental health promotion.60 Indeed, it is not yet included in the DSM-5. Like many areas of men’s mental health, this is an underresearched and underrecognized issue, passing under the radar of both psychiatry and society.

Health Service Utilization

Much research from across the Western world indicates that men underutilize mental health services in comparison to women. In North America, women are roughly twice as likely to attend mental health services as men.61 Likewise, in Australia, men are 11% less likely than women to see a psychiatrist (7.5% v. 8.3%) and 18% less likely to see other mental health professionals (6.9% v. 8.4%).62 Similar findings have been found in other developed countries.63–65

The most common interpretation for men’s low rates of service utilization surround masculine gender socialization.66 It is hypothesized that men are socialized to be stoic, stubborn, and self-reliant in the face of adversity. As such, seeking professional help for mental health issues may contradict these deeply held notions of masculinity that make up a core part of many men’s identity.67,68 As such, many men make the decision not to use mental health services, as this could be perceived (by themselves and others) as “unmanly” and a sign of weakness.

To this end, numerous initiatives have attempted to counter men’s alleged negative attitude to seeking help. This includes Canada’s Man-Up Against Suicide project69 and aspects of Australia’s beyondblue organization.70 Such programs may account, at least in part, for modest increases in the use of mental health services among men in recent years.71 However, the common interpretation that men’s lack of service engagement is due to men’s stubbornness is only part of a much more complex picture and also can reasonably be construed as “victim blaming,” ignoring the role played by social determinants and the cultural climate as well as any possible problems in the existing mental health system.

For example, men’s perspectives on mental health and help seeking are not developed in isolation; they are informed by a broader cultural discourse that affects their experiences and decisions. Notions of masculinity and femininity arise from parenting, education, popular culture, and the media. All this can colour the definition and experience of vulnerability, emotional distress, and mental illness by gender.72

Indeed, some research indicates that societal sympathy is particularly lacking for men with mental health issues, which Stanford University Professor Philip Zimbardo calls an “empathy gap.” For example, a content analysis of Canadian newspaper articles from 2010 to 2011 found that women with mental illness are presented much more sympathetically by the media than men with mental illness.73 A similar study found that the media tended to berate men for being silent about their depression and their reluctance to seek help rather than encourage men to take action.74 This suggests a need for distal action.

The link between social gender norms and men’s reluctance to seek help is well established.75,76 However, much less attention has been paid to the impact that these social norms have on health care providers. Inevitably, health care providers (as well as health policy-makers) will be influenced by gender norms and unconscious gender biases when treating a man or a woman. At present, there has been little research on gender biases affecting men in psychiatric clinics. With that said, much research indicates that traditional notions of masculinity are institutionalized in the wider medical system.77 Indeed, a qualitative study found that health care providers often encourage “stoical masculinity” among suffering male cancer patients.78, p 99 Other research suggests that physicians spend significantly less time with men than women during health visits79–81 and that men are often given fewer and briefer explanations.79,81,82

In mental health specifically, social gender norms may result in professionals being less likely to probe for emotional or psychological suffering in men.66,67 Some studies have found that health care providers are both less likely to diagnose mental illness in men than women and are less likely to act upon mental illness in men once it is detected.83 Likewise, a qualitative study from Toronto found that dismissive and intolerant attitudes of health care providers were implicated in suicidal men’s decision to use alcohol, drugs, and sex in response to mental health issues rather than utilizing formal services.84

Gendered attitudes of health care providers, either implicitly or explicitly communicated, may reinforce some men’s beliefs that mental health services are not appropriate for them. They may also intensify (and unintentionally validate) men’s tendency to downplay or minimize the severity of mental health symptoms in the clinical encounter.85

All of the above have led some scholars to suggest that mental health services are inherently “feminized,”2,86 as they prioritize factors such as talk, emotional vulnerability, and in-depth self-disclosure as core aspects of healing (all allegedly feminine traits). Some have argued that this is a consequence of a predominantly female workforce; according to figures from the US Department of Labor, 68% of psychologists, 82% of social workers, and 88% of psychiatric aides are women.87 Although some men may prefer consultation with female health professionals, it has been suggested that many men may feel especially self-conscious about disclosing issues to women.88 This raises the issue of choice and gender matching of client and clinician, which has received little attention in comparison to ethnic matching.89 This should be an area for future research.

Conclusion

Attention to men’s mental health has been increasing in recent years. Hitherto, men’s mental health issues have often been explained through deficit-based models, frequently involving victim blaming. In this article, we propose a new public health–oriented approach, which includes documenting and addressing distal and proximate social determinants of mental health as well as a critical examination of the nature of mental health services. Evidence suggests that individual men may need to change; however, health service providers and society as a whole may also need to change. This approach may help address what many are calling the “silent crisis” of men’s mental health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sacha Fernandez and Rachel Catterall for their help researching for this article as well as helpful feedback on earlier drafts from Dan Bilsker, JiaWei (Steve) Wang, and Michael Creed.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sommers CH. The war against boys: how misguided policies are harming our young men. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farrell W. The myth of male power: why men are the disposable sex. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sax L. Boys adrift: the five factors driving the growing epidemic of unmotivated boys and underachieving young men. New York: Basic Books; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kleinfeld J. The state of American boyhood. Gender Issues. 2009;26(2):113–129. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bilsker, this issue.

- 7. Navaneelan T. Health at a glance. Suicide rates: an overview. Catalogue no. 82-624-X. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chachamovich E, Kirmayer J, Haggarty J, et al. Suicide among Inuit: results from a large, epidemiologically representative follow-back study in Nunavut. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(6):268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64(2):1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pearson C, Janz T, Ali J. Health at a glance. Mental and substance use disorders in Canada Catalogue no. 82-624-X Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. British Columbia Coroners Service. Fentanyl-detected illicit drug overdose deaths: January 1, 2012 to April 30, 2017 Burnaby (BC): Office of the Chief Coroner, Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brault MC, Lacourse É. Prevalence of prescribed attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medications and diagnosis among Canadian preschoolers and school-age children: 1994–2007. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. [Updated; cited 2017 Jul 28] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/adhd.htm.

- 14. Fombonne E. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(6):591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brugha T, McManus S, Meltzer H, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in adults living in households throughout England: report from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007 Leeds: NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kessler RC, Coccaro EF, Fava M, Jaeger S, Jin R, Walters E. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):669–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Demmer DH, Hooley M, Sheen J, McGillivray JA, Lum JA. Sex differences in the prevalence of oppositional defiant disorder during middle childhood: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(2):313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, et al. Ontario child health study: II. Six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(9):832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006;36(5):699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patten SB, Williams JV, Lovarato DH, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of major depressive disorder in Canada in 2012. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(1):23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watterson R, Williams J, Lovarato D, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(1):24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus J. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1994;115(3):424–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parker G, Fletcher K, Paterson A. Gender differences in depression severity and symptoms across depressive sub-types. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(6):486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walinder J, Rutz W. Male depression and suicide. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(S2):S21–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Real T. I don’t want to talk about it: overcoming the secret legacy of male depression. Dublin: Newleaf; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cochran SV, Rabinowitz FE. Men and depression: clinical and empirical perspectives. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, et al. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bolton M, Robinson J, Sareen J. Self-medication of mood disorders with alcohol and drugs in the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Egeland JA, Hostetter AM. Amish study, I: affective disorders among the Amish, 1976-1980. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(1):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lowenthal K, Goldblatt V, Gorton T, et al. Gender and depression in Anglo-Jewry. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1051–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin L, Neighbors H, Griffith D. The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs. women: analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(10):1100–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moller-Leimkuhler A. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? Eur Ach Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bilsker D, White J. The silent epidemic of male suicide. BC Med J. 2011;53(10):529–534. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: meta-analyses. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74(3):264–282. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Artazcoz L, Benach J, Borrell C, et al. Unemployment and mental health: understanding the interactions among gender, family roles, and social class. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):82–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang J, Patten S, Currie SA. Population-based longitudinal study on work environmental factors and the risk of major depressive disorder. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(1):52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roberts SE, Jaremin B, Lloyd K. High-risk occupations for suicide. Psychol Med. 2013;43(6):1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Autor D, Wasserman M. Wayward sons: the emerging gender gap in labor markets and education. Washington (DC): Third Way; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Burrows S, Auger N, Tamambang L, et al. Suicide mortality gap between Francophones and Anglophones of Quebec, Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(7):1125–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Government of Canada. EI program characteristics for the period of September 10, 2017 to October 07, 2017. [Updated; cited 2017 Sep 28]. Available from: http://srv129.services.gc.ca/eiregions/eng/rates_cur.aspx.

- 42. Bowlby G, McMullen K. Provincial drop-out rates: trends and consequences. Education Matters. 2005;2(4):81–004x. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Action Group on Student Retention and Success in Quebec. Knowledge is power: toward a Quebec-wide effort to increase student retention. Montreal: McKinsey and Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sakinofsky I, Webster G. The epidemiology of suicide in Canada In: Cairney J, Streiner DL, editors. Mental disorder in Canada: an epidemiological perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2010. p 357–389. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Statistics Canada. Canadian postsecondary enrolments and graduates, 2013/2014. [Updated; cited 2017 Jul 28] Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/151130/dq151130d-eng.htm.

- 46. Gove W. The relationship between sex roles, marital status, and mental illness. Soc Forces. 1972;51(1):34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rotermann M. Marital breakdown and subsequent depression. Health Rep. 2007;18(2):33–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alexander J. Depressed men: an exploratory study of close relationships. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Department of Justice, Government of Canada. Selected statistics on Canadian families and family law. [Updated; cited 2017 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/famil/stat2000/index.html.

- 50. Sinha M. Parenting and child support after separation or divorce Catalogue no. 89-652-X Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Felix DS, Robinson WD, Jarzynka KJ. The influence of divorce on men’s health. J Men Health. 2013;10(1):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, et al. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Neglect. 1992;16(1):101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thompson MP, Kingree JB, Desai S. Gender differences in long-term health consequences of physical abuse of children: data from a nationally representative survey. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chandy JM, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Gender-specific outcomes for sexually abused adolescents. Child Abuse Neglect. 1996;20(12):1219–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(19):1961–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2009;50(3):254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ramchandani PG, O’Connor TG, Evans J, et al. The effects of pre-and postnatal depression in fathers: a natural experiment comparing the effects of exposure to depression on offspring. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2008;49(10):1069–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ramchandani P, Stein A, Evans J, et al. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective population study. Lancet. 2005;365(9478):2201–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vasiliadis HM, Lesage A, Adair C, et al. Do Canada and the United States differ in prevalence of depression and utilization of services? Psychiatric Serv. 2007;58(1):63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: summary of results, 2007. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dezetter A, Briffault X, Bruffaerts R, et al. Use of general practitioners versus mental health professionals in six European countries: the decisive role of the organization of mental health-care systems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(1):137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gagné S, Vasiliadis HM, Préville M. Gender differences in general and specialty outpatient mental health service use for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Möller-Leimkühler AM. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Courtenay W. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Heifner C. The male experience of depression. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1997;33(2):10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Man-Up Against Suicide. Home page. [Updated; cited 2017 Jul 28]. Available from: manupagainstsuicide.ca.

- 70. beyondblue. Home page. [Updated; cited 2017 Jul 28]. Available from: beyondblue.org.au.

- 71. Harris MG, Diminic S, Reavley N, et al. Males’ mental health disadvantage: an estimation of gender-specific changes in service utilisation for mental and substance use disorders in Australia. Aust NZ J Psychiat. 2015;49(9):821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Inckle K. Strong and silent: men, masculinity, and self-injury. Men Masc. 2014;17(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Whitley R, Adeponle A, Miller AR. Comparing gendered and generic representations of mental illness in Canadian newspapers: an exploration of the chivalry hypothesis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(2):325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bengs C, Johansson E, Danielsson U, et al. Gendered portraits of depression in Swedish newspapers. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(7):962–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gough B. Try to be healthy, but don’t forgo your masculinity: deconstructing men’s health discourse in the media. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(9):2476–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Johnson J, Oliffe J, Kelly M, et al. Men’s discourses of help-seeking in the context of depression. Sociol Health Ill. 2012;34(3):345–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moynihan C. Men, women, gender and cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2002;11(3):166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Broom A. The eMale: prostate cancer, masculinity and online support as a challenge to medical expertise. J Sociol. 2005;41:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Brooks GR. Masculinity and men’s mental health. J Am Coll Health. 2001;49(6):285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Blanchard CG, Ruckdeschel JC, Blanchard EB, et al. Interactions between oncologists and patients during rounds. Ann Int Med. 1989;99:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Waitzkin H. Doctor-patient communication: clinical implications of social scientific research. J Am Med Assoc. 1984;252(17):2441–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, et al. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(6):381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Stike C, Rhodes AE, Bergmans Y, et al. Fragmented pathways to care: the experiences of suicidal men. Crisis. 2006;27(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. O’Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G. ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Morison L, Trigeorgis C, John M. Are mental health services inherently feminised? Psychologist. 2014;27(6):414–416. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. Labor force statistics from the current population survey. [Updated; cited 2017 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

- 88. Banks I. No man’s land: men, illness, and the NHS. BMJ Brit Med J. 2001;323(7320):1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ziguras S, Klimidis S, Lewis J, et al. Ethnic matching of clients and clinicians and use of mental health services by ethnic minority clients. Psychiat Serv. 2003;54(4):535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]