Abstract

Objective

Evaluate effectiveness and harms of interventions for patellar tendon related pain in children and adolescents.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Medline via Pubmed, Embase via OVID, CINAHL via Ebsco, SportDiscus up until 24 November 2017 were searched.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Inclusion criteria were (1) controlled or randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs), (2) participants with diagnosis of patellar tendon related disorder, (3) participants≤18 years of age at enrolment and (4) published in a peer-reviewed English or Scandinavian language journal.

Results

Of 530 studies identified, eight were included after screening, with three included in data synthesis. To be included in data synthesis, we required studies to have included (and have data available for) a minimum of 10 participants under 18 years. All studies were rated as being at high risk of bias. For adolescents with patellar tendinopathy, one RCT compared eccentric exercises to usual care and found no difference between groups. In adolescents with Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD), injection of local anaesthetic with dextrose proved superior to either usual care or local anaesthetic alone (three armed RCTs). In a retrospective case controlled study in adolescents with OSD, surgery provided no benefit over conservative management in terms of persistent symptoms and had a higher complication rate.

Conclusion

There is weak evidence to support the use of dextrose injection with local anaesthetic and no evidence to support the use of specific types of exercises to treat children/adolescents with OSD/patellar tendinopathy. Until further evidence arises, clinicians should include load modification and advise on a return to sport based on symptoms.

Keywords: tendinopathy, tendinosis, tendon, children, adolescent

What is already known?

Patellar tendon related pain is relatively common in physically active children and adolescents.

What are the new findings?

Only three randomised controlled clinical trials have tested an intervention versus comparator in a population with a reasonable number of children and adolescents.

All studies had a high risk of bias. Specifically, ‘usual care’ provided was highly variable which provided a substantial source of bias.

In one study, hyperosmolar dextrose injection (combined with local anaesthetic) was superior to both local anaesthetic injection and usual care.

This review found no evidence to justify surgery for Osgood-Schlatter disease.

Introduction

Patellar tendon related pain conditions are common in children and adolescents, appear to begin in childhood and increase in prevalence during adolescence up to age 18.1 Patellar tendon related pain is an umbrella term, which encompasses Osgood-Schlatter’s disease (OSD), Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease and patellar tendinopathy. OSD affects 1 in 10 adolescents and as many as 1 in 5 in certain sports.2 3 There is a paucity of high-quality evidence relating to prognosis.

In one prospective cohort study in 18 adolescents with OSD, even 2 years after initial diagnosis, over 60% demonstrated persistent patellar tendon changes (evaluated by ultrasonography) and continued to display deficits in functional performance. Individuals with a history of OSD can experience persistent pain, years later, in their early 20s,4–6 associated with OSD lesions, underscoring that these pain complaints may not go away on their own if treated with a ‘wait and see’ approach. Interventions which reliably improve long-term outcomes are needed.7

While there is a large body of randomised trials and high-quality systematic reviews for managing patellar tendon related disorders in adults, there is a complete lack of systematic evaluations of treatment strategies specifically for adolescents and children.8 Considering patellar tendon related pain seem to start around the age of 10,1 there is a need for evidence and syntheses specific to this population. This is especially important considering some of these patellar tendon related pain complaints are unique to adolescent period, for example, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome and OSD.

The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review (and if possible, meta-analysis) of the benefits and harms of different treatment options for patella tendon related pain in children and adolescents.

Methods

The systematic review was prospectively registered the review in PROSPERO (registration number 82736 link). The review was informed according to the Cochrane guidelines and is reported according to the PRISMA statement.

Data sources and searches

We carried out a systematic search in the following bibliographic databases: Medline via Pubmed, Embase via OVID, CINAHL via Ebsco, SportDiscus up until 24 November 2017. The search terms and strategy were developed with a research librarian and are available in online supplementary material 1.

bmjsem-2018-000383supp001.docx (195.5KB, docx)

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies evaluating any intervention for any type of patellar tendon related pain in children or adolescents were eligible for inclusion, providing the design included an intervention and a comparator. Specifically, non-randomised controlled clinical trials and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including semi/quasi-randomised and cluster randomised trials) were eligible. Any therapeutic intervention or control treatments were included (including, but not restricted to, non-surgical interventions, injection-based interventions, exercise, surgical interventions or standard care/wait and see and so on). Studies had to include children or adolescents (aged under 18 years), with patellar tendon related pain. We included any publications in English or Scandinavian languages. Studies were excluded if reporting on primary complaints of patellofemoral joint disorders including patellofemoral pain a, patellofemoral instability, acute traumatic causes of knee pain, inflammatory arthritis, or if they included a population age >18 years. If the study included a mixed-age population extending across the age limits in our inclusion criteria, we requested age-specific data for those <18 years from trial authors.

Selection of studies

Duplicates were removed and relevant studies identified from the search were imported into Covidence for screening. Studies were independently screened by title and abstract by two authors (TO and GC). This was followed by full text evaluation of the selected studies from the first selection step by both authors. Disagreement between the two reviewers was solved by consensus involving a third reviewer (BD).

Outcomes

Our primary domains of interest were pain, function and sport participation. Reports on the number and type(s) of adverse effects (harms) related to interventions were extracted and recorded. Additionally, all other reported outcomes were considered of potential interest and extracted. We did not impose any restrictions on endpoints; a priori we defined endpoints of interest as immediate effects (0–7 days after receiving treatment), short-term (1 week to 3 months), medium-term (3–6 months) and long-term (above 6 months).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (GC and BD) independently extracted data. Data were extracted using a custom data extraction sheet in Covidence. Data regarding study design and setting, sample characteristics (including diagnoses, age, sex, demographics), inclusion criteria, intervention types and characteristics, follow-up, compliance, withdrawals, outcomes and any adverse events were extracted. Inconsistencies were resolved by consensus discussion. A third review (MSR) was available for disagreements that could not be resolved by discussion.

If relevant data were not available from full-text articles or trial registrations, authors were contacted to provide this information. For studies including mixed populations (both adolescents and adults), individual participant data for those 18 and under were requested. Authors were sent two subsequent reminders over 6 weeks. Studies were excluded from data synthesis if individual patients were not provided or studies included less than 10 participants under 18.

Risk of bias assessment

Two independent raters (BD and GC) assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Each trial was evaluated across seven domains of bias, including one or more items that are were appraised in two parts. Assessment followed the description in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions, V.5.1 (Part 2: 8.5.1) as follows. First, the relevant trials’ characteristics related to the item were summarised. Second, each bias domain was judged as high or low risk of bias, according to their possible effect on the results of the trial. When the possible effect was unknown or insufficient detail was reported, the item was judged as unclear. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. A third party (MSR) was available in case of persistent disagreement.

Data analysis

It was specified a priori, a meta-analysis would only be performed if data were available for similar time-points, outcomes and interventions. As this was not possible, we conducted a narrative synthesis of the results based on the domains of interest.

Results

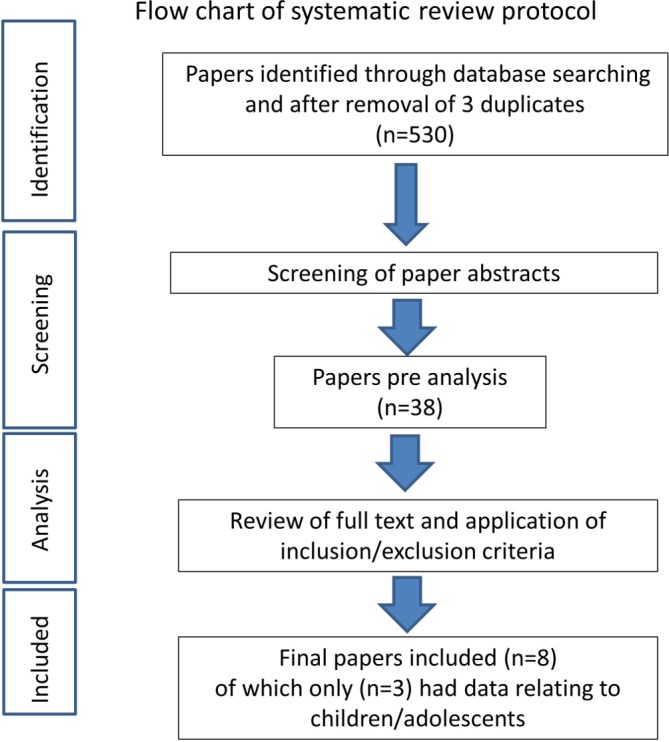

A total of 530 studies were identified by the search strategy. After screening, eight studies were identified as eligible for inclusion (figure 1, PRISMA flowchart). Of these, seven were RCTs, and one was a retrospective non-randomised controlled trial. Two studies specifically included an adolescent-only population (both OSD). The other six studies were on patellar tendinopathy and included a mixed sample. Study characteristics are provided in table 1 and table 2. Additional information of included studies is available in online supplementary material 1 (S1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of systematic review protocol.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Author | Year | Journal | Setting | Population | Age | Type of study | Intervention/s | Comparator | Outcomes | Time points |

| Biernatet al 11 | 2014 | J Strength Cond Res | University physical therapy | Male volleyball players with patellar tendinopathy | Mixed | Randomised controlled trial | Specific exercises including eccentric decline squat | Continued competitive activity and functional exercises | Visa-P Maximal power Jump height | Baseline, 12 weeks, 24 weeks |

| Cannellet al 16 | 2001 | Br J Sports Med | Sports medicine centre | Mixed athletes with jumper’s knee | Mixed | Randomised controlled trial | Drop squat exercises | Leg extension/curl exercises | Pain score Quadriceps moment Hamstring moment | Baseline, 4 weeks |

| Jonsson et al 14 | 2005 | Br J Sports Med | Sports medicine unit | Athletes with jumper’s knee | Mixed | Randomised controlled trial | Eccentric exercises | Concentric exercises | VISA Pain scores (VAS) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks |

| Topolet al 9 | 2011 | Pediatrics | Physical medicine | Children with Osgood Schlatter’s who played sports | All <18 years old | Randomised controlled trial | Local anaesthetic and Local anaesthetic plus dextrose | Usual care | NPSS (Nirschl Pain Phase Scale) | Baseline, 3 months |

| Trailet al 10 | 1988 | J Pediatr Orthop | Secondary care—Orthopaedics | Children with Osgood Schlatter’s | All <18 years old | Retrospective non-randomised parallel group design | Tibial sequestrectomy and mixture of cast/injections/physiotherapy | Reduction of activity/sport avoidance and mixture of cast/injections/physiotherapy | Proportion symptomatic Complication rate | Variable as at final review |

| Wanget al 12 | 2007 | Am J Sports Med | Orthopaedic surgery department | Patients with chronic patellar tendinopathy | Mixed | Randomised controlled trial | Shockwave treatment followed by period of light activity | NSAIDs, physiotherapy and exercise program | Pain scores VISA Knee range of movement | Baseline, variable—2 to 3 years |

| Willberget al 15 | 2011 | Br J Sports Med | Sports medicine unit | Patients with patellar tendinopathy | Mixed | Randomised controlled trial | Arthroscopic shaving | Sclerosing polidocanol injections | VAS at rest VAS on activity Satisfaction | Baseline, variable—approximately 12 months |

| Van Ark et al 13 | 2016 | J Sci Med Sport | Physiotherapy department | Volleyball/basketball players with patellar tendinopathy | Mixed | Randomised controlled trial | Isometric exercises | Isotonic exercises | Pain score | Baseline, 4 weeks |

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 2.

Details of study participants demographics and whether data were provided

| Author | Year | Journal | Intervention group age | Comparator group age | Intervention group sex | Comparator group sex |

| Biernat et al 11 | 2014 | J Strength Cond Res | 17.2 (0.6) | 16.5 (0.8) | All male | All male |

| Cannell et al 16 | 2001 | Br J Sports Med | No response from author within time limit | |||

| Jonsson et al 14 | 2005 | Br J Sports Med | Author confirmed age specific data not obtainable | |||

| Topol, et al 9 | 2011 | P ediatrics | 13.3 (range 10–17) | 51 boys and three girls | ||

| Trail et al 10 | 1988 | J Pediatr Orthop | 13 years 9 months (range 11–17) | 12 years 7 months (range 10–17) | Not stated | Not stated |

| Wang et al 12 | 2007 | Am J Sports Med | Author confirmed no participants under age 18 took part in the study (note study did state age range lower limit was 16) | |||

| Willberg et al 15 | 2011 | Br J Sports Med | No response from author within time limit | |||

| Van Ark et al 13 | 2016 | J Sci Med Sport | Only one under 18 year old participant took part hence study excluded from data analysis |

bmjsem-2018-000383supp002.docx (188.7KB, docx)

Osgood-Schlatter

Topol et al 9 compared usual care versus local anaesthetic versus local anaesthetic and dextrose in a threearmed RCT for OSD. The outcome was the Nirschl Pain Phase Scale (NPPS) at 3 months. The superiority of dextrose and local anaesthetic compared with local anaesthetic alone was shown (SMD: 0.83, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.45, p=0.006) or usual care (SMD: 1.66, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.36, p<0.0001) (see online supplementary material for Forest plots).

bmjsem-2018-000383supp003.png (16.1KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp004.png (18.5KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp005.png (15.3KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp006.png (15.8KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp007.png (8KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp008.png (5.8KB, png)

Trail10 compared surgery (tibial sequestrectomy) with conservative treatment in a retrospective non-randomised parallel group study of OSD. Participants were categorically rated as ‘symptomatic’ or ‘asymptomatic’ at final review approximately 5 years from initial diagnosis. The odds of being asymptomatic was not significantly different with surgery compared with conservative treatment (OR 1.48, 95% CI 0.33 to 6.65) (see online supplementary material for Forest plots). Several patients in both groups were subject to other interventions (including refraining from sport, cast treatment, physiotherapy and steroid injections).

Patellar tendinopathy

Only one11 of the six studies including mixed populations of adolescents and adults was included in the data synthesis (details of exclusion outlined below). This study by Biernat et al compared the effect of usual care to eccentric exercises in male adolescents on patient-recorded outcomes (VISA-P questionnaire). There was no significant difference between groups at either 12 or 24 weeks (SMD: 0.45, 95% CI −0.44 to 1.35, p=0.32 and SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.26, p=0.42, respectively) (see online supplementary material for Forest plot) table 2.

Two studies were excluded from data synthesis as they did not contain a large enough sample of adolescents (N=0 and N=1 adolescent included).12 13 One study was excluded from data synthesis because data for adolescents could not be extracted,14 and two studies could not be included in the data synthesis due to non-response to requests for data for adolescent participants.15 16

Harms

Only one study reported on potential harms. Trail reported a lower overall complication rate for conservative treatment,10 compared with surgery (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.38) (see online supplementary material for plot harms OR).10 Complications were primarily presence of bony prominence (6 in conservative group and 18 in surgical group). The surgical group had additional complications (three with areas of anaesthesia lateral to scar, one infection, one wound dehiscence, one stiffness and one recurvatum).

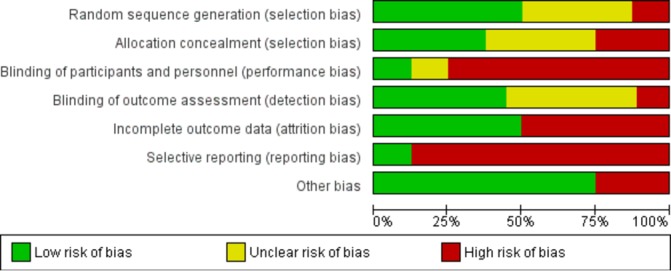

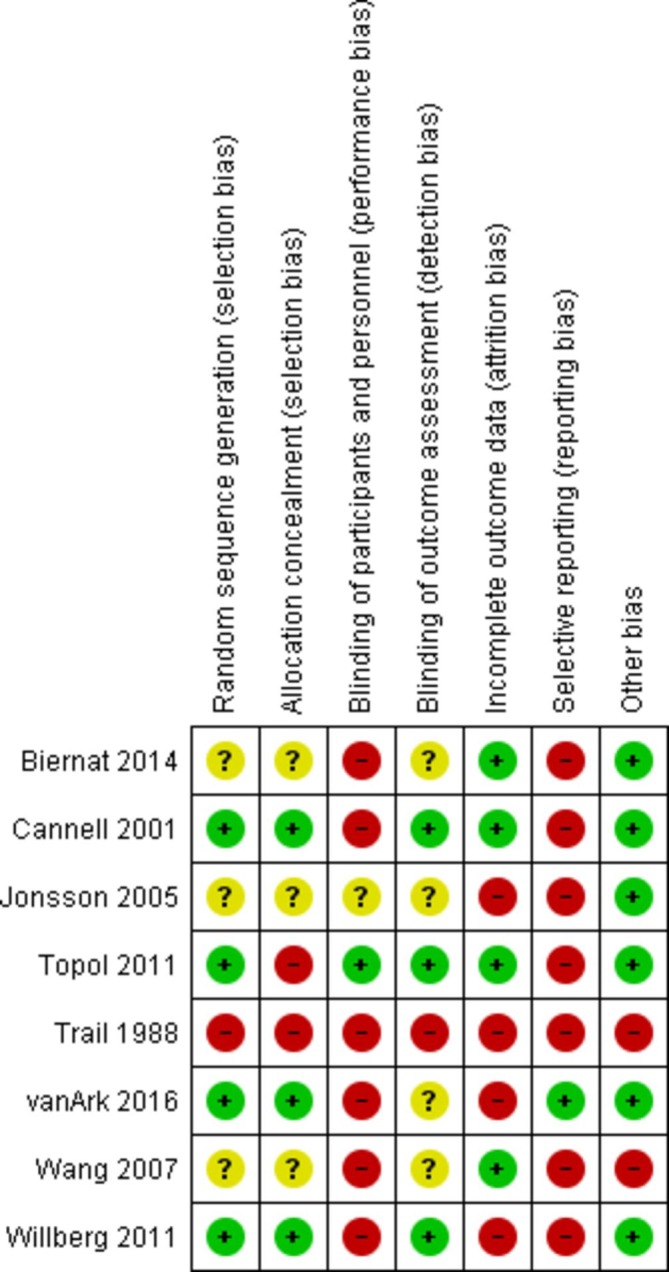

Risk of bias

Overall, all studies were deemed to be at high risk of bias, particularly in the domains of reporting bias and performance bias (figure 2 and figure 3)

Figure 2.

Risk of bias within studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary graph.

Studies identified and excluded at each stage are detailed in figure 1.

Discussion

The key finding of this review is the lack of studies assessing the effectiveness of interventions for patellar tendon related pain in children and adolescents. Despite commonality of these disorders in this population, only three studies have assessed any intervention. All three were at high risk of bias, especially reporting bias, blinding and had significant methodological weaknesses (with one being a retrospective parallel group case-series). This makes in nearly impossible to guide clinical practice on how to best to manage these common pain complaints in children and adolescents.

Adults and adolescents—potentially not the same

The problem is that while there is evidence supporting certain interventions (eg, tendon loading programmes) for patellar tendon related pain in adults,17 the findings of these cannot be directly transferred into children and adolescents. The pathological features of tendinopathy includes increased cellularity, a loss of collagen structure and chondroid metaplasia.18 19 There is an increasing body of evidence demonstration the role of chronic inflammation as part of this degenerative process18 20 21 Tendon loading programmes have been associated with an improved collagen turnover in adults suggesting a possible mechanisms of effect. However, an important difference between adults and adolescents is the maturity of the patellar tendon insertion, the enthesis organ.22 It is a possible that overly aggressive sporting activity and tendon loading during development may actually have a negative long-term impact in terms of both tendon structure and the risk of adulthood symptoms. Notably, a recent study has shown that increased sporting activity has a detrimental impact on the developing hip, which supports this theory. As we do not yet have a clear understanding of how the pathology of patellar tendon related pain during maturation, caution needs to be taken in applying such effective interventions from adults to children and adolescents. This is particularly as adolescence is proposed to be a critical time for the formation of normal tendon attachment.23 24

Devil in the detail

One of the serious concerns with the included studies is the multiple differences in treatment between control and experimental arms. For example, in Topol et al 9 the control group did not have a period of rest, which was in contrast to both injection therapy groups. This makes it difficult to elucidate if the observed effects were actually due to the intervention or to the removal of aggravating activities. Furthermore, a dextrose injection at 3 months was used as an ‘incentive’ for study participation and offered to all participants that did not reach an NPPS score of 0 (regardless of treatment allocation), to avoid dropout in the control arm. This could potentially influence participants’ reporting, if they had a favourable perception of the injection, and reported lower outcomes to receive it.

The high frequency of patellar tendon related disorders in the sporting population is consistent with an ’overuse’ type aetiology. In this context, any advice on activity modification and the manner in which it is delivered may be crucial in influencing both short-term and long-term outcomes. Keeping this in mind, it is arguable what constitutes ‘usual care’ in daily practice and in the included studies may have been. The ‘usual care’ was highly variable and included factors such as the degree to which sporting activity was continued and the degree to which pain was experienced and/or allowed during sport or exercises. In the study by Topol et al,9 only participants in the injection arms were encouraged to engage in a sporting activity, only if the activity was not accompanied or followed by pain during the period of treatment. This contrasted with Biernat et al in which both experimental and control groups were subject to the same advice as regards continuing sporting activity.11

Harms

The study by Trail10 demonstrated a significantly higher complication rate with surgery versus conservative treatment, indicating that currently the use of surgery in this context should only take place in the more regulated context of a clinical trial. Notably, no studies analysed longer term outcomes into early adulthood, highlighting an area for future research.

Lack of knowledge hampers clinical practice

The absence of high-quality evidence presents a challenge to clinicians treating children and adolescents with patellar tendon related pain. Adolescence is a key developmental period, with a mature proximal patellar tendon enthesis occurring after peak height velocity.25 Given that patellar tendon structure is a predictor for pain,26 it is reasonable to argue that caution should be exercised when treating patients with an immature enthesis. Training beyond pain in order to satisfy short-term sporting objectives could have negative long term implications for the individual.27 Until further evidence arises, clinicians should be aware of the potential differences in patellar tendon related pain between adolescents and adults. These types of pain complaints are often associated with high levels of sports participation and sports specialisation. As sustained overload is thought to be a risk factor for developing, for example, OSD,28 it seems sensible that the mainstay of treatment include some form of load management. This type of treatment could include education where adolescents and parents are taught to modify training and loading (including recovery) based on symptoms but this has yet to be evaluated in a clinical trial.

Future research

Malliaras et al 17 concluded that high-quality studies comparing different loading programmes and evaluating clinical and mechanistic outcomes are needed in both Achilles and patellar tendinopathy rehabilitation in adults.17 The evidence relating to adolescents and children is worse, and this is concerning given the potential long-term consequences of overuse on the developing bone tendon interface. Understanding the impact of patellar tendon related pain disorders on the maturing tendon and entheses on both structural and functional outcomes in both the short and longer term, will be critical in the understanding of the natural history of patellar tendon related disorders in adolescents. It is also essential to explore the needs and preference of the young patients being treated. It is likely that these developing young individuals have specific needs which have yet to be addressed during treatment. Future studies may also wish to identify phenotypes associated with a particular poor prognosis to understand the trajectory of pain and impairments during this crucial period of life.

Despite the commonality of patella tendon related pain in children and adolescents, there is a paucity of evidence specific to this population to guide clinical practice. There is weak evidence to support the use of dextrose injections and no evidence to support the use of specific types of exercises. Further research is essential to ascertain how best to manage the many children and adolescents suffering from these pain complaints. Until further evidence arises, clinicians should include load modification and advise on a return to sport based on symptoms.

Footnotes

Contributors: BJFD, SH, SK and MSR contributed to study conception and design, data analysis, drafting of the article and critical revision of the article. GC and TO contributed to study design, data collection and analysis and the critical revision of the article. NT contributed to study design, data collection and critical revision of the article.

Funding: The TRYG Foundation is acknowledged for provided support for this project (Grant ID: 118547).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Simpson M, Rio E, Cook J. At What Age do children and adolescents develop lower limb tendon pathology or tendinopathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2016;46:545–57. 10.1007/s40279-015-0438-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Lucena GL, dos Santos Gomes C, Guerra RO. Prevalence and associated factors of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in a population-based sample of Brazilian adolescents. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:415–20. 10.1177/0363546510383835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kujala UM, Kvist M, Heinonen O. Osgood-Schlatter’s disease in adolescent athletes. Retrospective study of incidence and duration. Am J Sports Med 1985;13:236–41. 10.1177/036354658501300404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pihlajamäki HK, Visuri TI. Long-term outcome after surgical treatment of unresolved osgood-schlatter disease in young men: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92(Suppl 1):258–64. 10.2106/JBJS.J.00450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eun SS, Lee SA, Kumar R, et al. Direct bursoscopic ossicle resection in young and active patients with unresolved Osgood-Schlatter disease. Arthroscopy 2015;31:416–21. 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Circi E, Beyzadeoglu T. Results of arthroscopic treatment in unresolved Osgood-Schlatter disease in athletes. Int Orthop 2017;41:351–6. 10.1007/s00264-016-3374-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaya DO, Toprak U, Baltaci G, et al. Long-term functional and sonographic outcomes in Osgood-Schlatter disease. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1131–9. 10.1007/s00167-012-2116-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rathleff MS, Vicenzino B, Middelkoop M, et al. Patellofemoral pain in adolescence and adulthood: same same, but different? Sports Med 2015;45:1489–95. 10.1007/s40279-015-0364-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Topol GA, Podesta LA, Reeves KD, et al. Hyperosmolar dextrose injection for recalcitrant Osgood-Schlatter disease. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1121–e1128. 10.1542/peds.2010-1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trail IA. Tibial sequestrectomy in the management of Osgood-Schlatter disease. J Pediatr Orthop 1988;8:554–7. 10.1097/01241398-198809000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biernat R, Trzaskoma Z, Trzaskoma L, et al. Rehabilitation protocol for patellar tendinopathy applied among 16- to 19-year old volleyball players. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:43–52. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31829797b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang CJ, Ko JY, Chan YS, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave for chronic patellar tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:972–8. 10.1177/0363546506298109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Ark M, Cook JL, Docking SI, et al. Do isometric and isotonic exercise programs reduce pain in athletes with patellar tendinopathy in-season? A randomised clinical trial. J Sci Med Sport 2016;19:702–6. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jonsson P, Alfredson H. Superior results with eccentric compared to concentric quadriceps training in patients with jumper’s knee: a prospective randomised study. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:847–50. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willberg L, Sunding K, Forssblad M, et al. Sclerosing polidocanol injections or arthroscopic shaving to treat patellar tendinopathy/jumper’s knee? A randomised controlled study. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:411–5. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.082446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cannell LJ, Taunton JE, Clement DB, et al. A randomised clinical trial of the efficacy of drop squats or leg extension/leg curl exercises to treat clinically diagnosed jumper’s knee in athletes: pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:60–4. 10.1136/bjsm.35.1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, et al. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med 2013;43:267–86. 10.1007/s40279-013-0019-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dean BJ, Gettings P, Dakin SG, et al. Are inflammatory cells increased in painful human tendinopathy? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:216–20. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, et al. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med 1999;27:393–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dakin SG, Martinez FO, Yapp C, et al. Inflammation activation and resolution in human tendon disease. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:ra173. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scott A, Lian Ø, Bahr R, et al. Increased mast cell numbers in human patellar tendinosis: correlation with symptom duration and vascular hyperplasia. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:753–7. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.040212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR, et al. Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites (‘entheses’) in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat 2006;208:471–90. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00540.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rudavsky A, Cook J, Magnusson SP, et al. Characterising the proximal patellar tendon attachment and its relationship to skeletal maturity in adolescent ballet dancers. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2017;7:306–14. 10.11138/mltj/2017.7.2.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ducher G, Cook J, Lammers G, et al. The ultrasound appearance of the patellar tendon attachment to the tibia in young athletes is conditional on gender and pubertal stage. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13:20–3. 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rudavsky A, Cook J, Magnusson SP, et al. Characterising the proximal patellar tendon attachment and its relationship to skeletal maturity in adolescent ballet dancers. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2017;7:306–14. 10.11138/mltj/2017.7.2.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McAuliffe S, McCreesh K, Culloty F, et al. Can ultrasound imaging predict the development of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1516–23. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Çakmak S, Tekin L, Akarsu S. Long-term outcome of Osgood-Schlatter disease: not always favorable. Rheumatol Int 2014;34:135–6. 10.1007/s00296-012-2592-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hall R, Barber Foss K, Hewett TE, et al. Sport specialization’s association with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J Sport Rehabil 2015;24:31–5. 10.1123/jsr.2013-0101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2018-000383supp001.docx (195.5KB, docx)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp002.docx (188.7KB, docx)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp003.png (16.1KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp004.png (18.5KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp005.png (15.3KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp006.png (15.8KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp007.png (8KB, png)

bmjsem-2018-000383supp008.png (5.8KB, png)