Abstract

Introduction

Suicide is increasing in the UK, and hanging is now the commonest mechanism. United Kingdom intensive care unit outcomes (including organ donation) after hanging have not been reported.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of cases admitted to a UK tertiary intensive care unit with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hanging/asphyxia. Case analysis divided between those with and without a history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and outcomes described using the cerebral performance category score.

Results

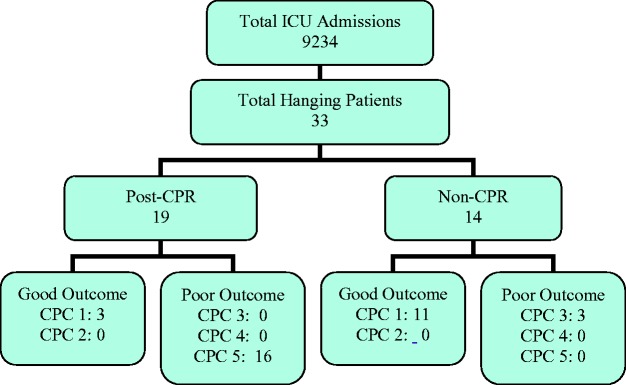

A total of 33 cases were reviewed, 19 with a history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (three survivors with cerebral performance category of 1–2), 14 without history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (14 survivors, 11 cerebral performance category score of 1, 3 cerebral performance category score of 3). Three cases went on to have a good neurological outcome with a cerebral performance category score of one, and 16 died. The three survivors only had bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and cardiac arrest was not independently confirmed. All three had a good neurological recovery despite two having hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy on computed tomography head. Of the three survivors, one received no temperature management and two received targeted temperature management. Median intensive care unit length of stay after hanging with cardiopulmonary resuscitation was 3.0 days (2.4–6.7 days). Fifteen patients were discussed with the organ donation specialist nurse, with six consenting to donation and six declining consent, with 18 solid organs donated. All 14 of those without a history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation survived, 11 with a cerebral performance category score of 1 and three having a cerebral performance category score of 3. No patients received active temperature management. Median intensive care unit length of stay in this group was 2.9 days (1.2–3.8).

Conclusions

Outcomes after confirmed cardiac arrest following hanging are poor, in keeping with existing international data, even in those surviving to intensive care unit admission. Despite low rates of consent to organ donation, the overall organ donation is high due to high referral rates. Despite the poor prognosis in this population, early initiation of full resuscitation should be offered to optimise survival and facilitate the possibility of donation.

Keywords: Hanging, asphyxia, intensive care, outcomes, critical care, organ donation, tissue and organ procurement, United Kingdom

Introduction

Suicide rates in the United Kingdom are rising, with an incidence of 10.9 deaths per 100,000 of the population. This increase is fuelled by an increase in numbers in Wales and Northern Ireland.1 Hanging is now the most common method of suicide for both sexes, accounting for 58 and 43% of suicides in males and females, respectively, with a concurrent increase in non-fatal self-harm by hanging.2 However, guidelines for management are not available, and outcomes and impact on UK critical care have not been reported. Decisions regarding admission to intensive care unit (ICU) following devastating brain injuries (DBI) are complex due to the lack of accurate early prognostic factors and highly resource intensive resuscitation. However, improved knowledge of likely outcomes of patients surviving to ICU admissions will help support families, who are known to value honest consistent information.3

Kim et al. recently described a large cohort of hangings from Korea, a country with the second highest suicide rate in the world (28.9 per 100,000 population).4,5 The authors identified significant outcome differences, with poor neurological outcomes in those suffering a cardiac arrest compared to those without an episode of cardiac arrest.4 Initial Glasgow coma score (GCS) on arrival to the Emergency Department (ED) and pH was reported as predictive of outcomes. In the 121 patients successfully resuscitated after cardiac arrest, only 5 (4.1%) recovered with a good neurological outcome (good outcome being predicted by higher first arterial pH and serum bicarbonate). The authors concluded that in those without cardiac arrest, survival was 100%, with 12/159 (7.5%) having a poor neurological outcome.

Outcomes from hanging are diverse, ranging from full neurological recovery to DBI including brain death. Patients with a history of hanging can become organ donors but are considered to be high-risk donors by the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) Blood and Transplant.6 This ‘high-risk donor’ status is applied to those donors who may pose an increased risk to the recipient due to their lifestyle or mode of death. There are concerns about the quality of donated organs, particularly lungs, due to both global tissue hypoxia and lung injury.7 Donation after an episode of hanging accounted for 211 potential donors out of 25,073 (0.8%) in a three-year period from April 2010 to March 2013. Nationally, 82% of potential (un-consented) donors proceed to donation after hanging, against a background of 74%. Overall ‘event’ rates (including death, transplant failure or graft failure), for all organs combined, are similar between donations after hanging compared to national average (10.7% from post-hanging donors compared to 12.6% for all donors). There is concern regarding the viability of lung transplant after hanging due to asphyxia and negative intra-thoracic pressures, but international survival rates appear comparable to unselected donors.7 In the UK, however, there were 29 lung transplants from post-hanging donors in a 10-year period (2003–2013), with 22 ‘events’ in the first year after transplant. This gives a rate of 76%, compared to 12.6% for all donors.6

In this case series from a UK tertiary critical care unit, we examine outcomes (including donation rates) for patients admitted to intensive care with a history of hanging.

Methods

Setting and design

This service evaluation was a retrospective analysis of hanging patients admitted to the general adult ICU of the University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff from February 2010 to October 2016. Patients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of ‘Hanging or Strangulation’ were included and divided into those who did have a period of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (post-CPR group) and those that did not have a period of CPR (non-CPR group) in the 24 h prior to admission to intensive care. The project was confirmed to be a service evaluation by the Innovation and Improvement Department and approved to continue without review by the local ethics committee.

Data collection

Data were collected from the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) data set, radiology reports, biochemistry records and patient notes; including ED records, ICU notes and ICU discharge letters. Organ donation data were retrieved from the audit data of the local NHS Blood and Transplant Service team. Where available, the data collected were based on that reported by Kim et al.4

Demographic data were age, sex, hanging time, hanging height, hanging type (complete versus incomplete) and presence of a hanging mark.

Pre-hospital variables included; first saturation, first heart rate, first cardiac rhythm, first GCS and pre-hospital airway management.

ED data included first recorded observations of arterial oxygen saturation, first respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, rhythm and results from the first ED arterial blood gas (ABG) (pH, bicarbonate and lactate).

ICU data included ICNARC score and predicted mortality, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score and predicted mortality, use of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) or targeted temperature management (TTM), length of stay (LOS), discharge destination, survival, cerebral performance category (CPC) at the time of ICU discharge. CPC was measured from discharge letters and entries regarding neurological progress in the clinical notes. Good outcome was defined as a CPC of 1–2, with poor outcome defined as CPC 3–5.

Radiological data included presence of positive findings on computed tomography (CT) head, CT cervical spine and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Neurophysiological assessment included electrical encephalogram or somato-sensory evoked potentials (EEG/SSEP).

Organ donation data were collected for referral, consent outcome, type of donation considered (donation after brain death (DBD) or donation after circulatory death (DCD)) and type of organs donated.

Data analysis

Descriptive data analysis was performed on SPSS v.24. Direct comparisons of outcome rates and predictors of outcome were not attempted as the numbers were likely to be too small to allow meaningful statistical analysis, and this would be outside the remit of the service evaluation. An anonymised data set is available for review on request to the corresponding author.

Results

There were a total of 9234 admissions to UHW ICU between 01 February 2010 and 31 October 2016. In this time period, there were 19 patients with the diagnosis of hanging with a history of CPR in the 24 h prior to admission, and 14 without a history of CPR, representing a total of 0.36% of ICU admissions. Combined mean age was 33 (range 17–73), with 28/33 (84%) being male. None of the patients had evidence of pre-existing major ill health, when assessed by ICNARC past medical history scoring. Breakdown of CPR status and neurological outcome is summarised in Figure 1. For demographics, interventions and outcomes, see Table 1.

Figure 1.

Number of admissions with hanging and subsequent neurological outcome. CPC: cerebral performance category.

Table 1.

Demographics and outcomes; CPR group.

| Case No. | Sex | Age | APACHE II score | Pred. mort. | LOS | PH GCS | ED GCS | pH | Bicarb. | CT HIE | Temp man. | Seizures | Outcome | CPC score | Active withdraw | SNOD referral | Donation consent | Donation type | Donated Organs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 36 | 12 | 28 | 2.5 | 3 | 3 | 6.89 | 10.0 | Yes | TH | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | yes | DCD | K. |

| 2 | M | 25 | 24 | 69 | 12.0 | 3 | 3 | 7.32 | 13.0 | Yes | TH | Yes | Died | 5 | No | No | N/A | UD | Nil |

| 3 | F | 56 | 25 | 72 | 2.3 | – | 3 | 7.15 | – | Yes | TH | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | DCD | L,K. |

| 4 | M | 41 | 27 | 78 | 1.3 | 3 | 3 | 6.87 | 8.9 | Yes | TH | No | Died | 5 | No | Yes | No | – | Nil |

| 5 | F | 26 | 8 | 18 | 3.2 | 3 | 3 | 7.30 | 18.0 | Yes | TH | Yes | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | DCD | K,P,V. |

| 6 | M | 22 | 13 | 31 | 8.5 | 3 | 7 | 7.24 | 19.2 | Yes | No | No | Lived | 1 | Yes | No | N/A | Lived | Nil |

| 7 | F | 30 | 15 | 38 | 3.0 | 3 | 3 | 7.33 | 17.0 | Yes | TH | Yes | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | yes | DBD | L,K. |

| 8 | M | 38 | 11 | 25 | 3.3 | – | 3 | 7.30 | 16.9 | No | TH | Yes | Died | 5 | No | Yes | N/A | UD | Nil |

| 9 | M | 17 | 21 | 59 | 0.8 | 3 | 3 | 7.17 | 15.9 | Yes | TTM | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | No | DBD | Nil |

| 10 | M | 33 | 18 | 48 | 6.1 | 3 | 3 | 6.85 | 9.3 | Yes | TTM | Yes | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | yes | DCD | L, K. |

| 11 | F | 29 | 28 | 80 | 3.0 | – | 3 | 6.89 | 8.5 | Yes | No | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | yes | DBD | K, L, P,V, E. |

| 12 | M | 55 | 20 | 56 | 2.1 | 3 | 3 | 6.99 | – | Yes | TTM | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | No | DBD | Nil |

| 13 | M | 41 | 5 | 12 | 13.7 | – | – | – | – | No | – | – | Died | 5 | – | Yes | N/A | UD | Nil |

| 14 | M | 47 | 16 | 41 | 2.4 | 3 | 3 | – | – | Yes | TTM | No | Died | 5 | No | Yes | N/A | UD | Nil |

| 15 | M | 36 | 6 | 14 | 2.6 | 7 | 5 | – | – | No | TTM | No | Lived | 1 | No | No | N/A | Lived | Nil |

| 16 | M | 50 | 20 | 56 | 3.2 | 3 | 3 | 6.93 | 10.9 | Yes | TTM | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | No | DCD | Nil |

| 17 | M | 26 | 8 | 18 | 6.7 | 3 | 3 | 7.03 | – | Yes | TTM | Yes | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | No | DCD | Nil |

| 18 | M | 73 | 13 | 31 | 2.9 | 3 | 3 | – | – | Yes | TTM | No | Died | 5 | Yes | Yes | No | DCD | Nil |

| 19 | M | 61 | 20 | 56 | 16.2 | 3 | 3 | 7.02 | 13.7 | Yes | TTM | Yes | Lived | 1 | No | – | – | – | – |

Bicarb.: arterial bicarbonate (mmol L–1); CPC: cerebral performance category; CT HIE: computed tomography evidence of hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy; Donation type (UD: uncontrolled death, DBD: donation after brain death, DCD: donation after circulatory death); Donated organs (K: kidneys, L: liver, V: heart valves, P: pancreas, E: eyes); ED GCS: Emergency Department Glasgow coma score; LOS: length of stay (days); N/A: not applicable; PH GCS: pre-hospital Glasgow coma score; Pred. Mort.: predicted mortality (percentage); Sex (M: male, F: female), Temp. Man.: temperature management (TH: therapeutic hypothermia, TTM: targeted temperature management); Pred. Mort.: predicted mortality; SNOD referral: specialist nurse in organ donation referral; –: unrecorded.

In the post-CPR group, median age was 36 years (interquartile range (IQR) 26–50). APACHE II and ICNARC scores were 16 (IQR 11–21) and 23 (18–28), respectively. Survival was 3/19 (16%). Initial pre-hospital rhythms were asystole 4, pulseless electrical activity 8, ventricular fibrillation 3 and sinus rhythm 3.

Pre-hospital and first ED GCS were the same; 3/15 in 14 cases (2 survivors), 7 in one case (who survived), 4 missing. Median ED GCS was three (inter-quartile range 3–3). Median ICU LOS was 3.0 days (2.4–6.7 days). However, in all three survivors, there was bystander CPR only, and cardiac output was present on arrival of paramedics. Therefore, cardiac arrest was not independently confirmed. All three were discharged to their normal residence and had a CPC score of 1, despite two having evidence of hypoxic encephalopathy on their CT head. The prognostic factors (as identified by Kim et al.) for the two in whom first ABG results were available showed an initial pH of 7.24 and 7.02 (group median 7.03) and serum bicarbonate of 19.2 and 13.7 mmol/L (group median 13.3 mmol/L).4

Of the post-CPR group, 6/19 patients developed seizures, all of whom died. All patients had a CT head and neck, with 16/19 showing evidence of hypoxic encephalopathy, and none having CT evidence of C-spine fracture. Three patients had EEGs or SSEPs (one showing hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE), one showing status epilepticus, and the last was non-diagnostic). No MRIs were performed. In terms of neuro-protection, seven had TH, and nine had TTM, and two had no temperature management.

Active treatment was withdrawn in 11 patients. Time to decision to withdraw was not collected, but LOS was used as a proxy. Four of these met the brain stem death criteria and were excluded, and in the remaining seven, the ICU LOS was 3.8 days. Four of these became donors and three did not (LOS 3.5 and 4.2 days). In the seven who had withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, all had HIE on CT head. Pupil response and GCS at time of withdrawal were not sought. No MRI was performed. One case of indeterminate prognosis underwent EEG & SSEPs (inconclusive due to noise) and was observed and subsequently discharged (LOS 16 days).

Fifteen patients were discussed or formally referred to a specialist nurse in organ donation (one data set missing for donation referral). Active treatment was withdrawn in 11 patients. Of the 15 discussed or referred with a specialist nurse, six consented to organ donation (two donation after brain death, four non-heart beating donations), and six declined consent. The remaining seven from the post-CPR group were ineligible due to uncontrolled death (four), or surviving (three). In total, six pairs of kidneys, four livers, and two pancreases were retrieved, as well as two sets of heart valves (totally 18 solid organs).

In the non-CPR group, median age was 38 (26–50), APACHE II score was 9.5 (5.75–11.25) and ICNARC score was 14.50 (13.0–20.0). Median GCS in ED was 5.5 (4.75–8.25, four unrecorded). For demographics, interventions and outcomes of the non-CPR group, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics and outcomes; non-CPR group.

| Case no. | Sex | Age | APACHE II Score | Pred. Mort. | LOS | PH GCS | ED GCS | pH | Bicarb. | CT HIE | Temp Man. | Seizures | Outcome | CPC Score | Active withdraw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 57 | 26 | 75 | 4.1 | 5 | 5 | 7.38 | 24.0 | No | TTM | 2 | Lived | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | M | 27 | 10 | 7 | 1.3 | 5 | – | 7.29 | 21.0 | No | No | 1 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | M | 45 | 12 | 14 | 16.8 | 3 | 7 | 7.22 | 17.0 | SDH | No | 2 | Lived | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | M | 47 | 5 | 3 | 0.8 | 6 | 4 | 7.16 | 18.0 | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | M | 29 | 8 | 5 | 2.9 | 3 | 6 | 7.14 | – | Yes | No | 1 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | F | 36 | 12 | 9 | 16.8 | – | – | 7.28 | 17.0 | Yes | TTM | 2 | Lived | 3 | 2 |

| 7 | M | 25 | 9 | 6 | 1.0 | – | – | 7.42 | 24.0 | Yes | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | M | 51 | 9 | 1 | 1.0 | – | – | 7.43 | 25.0 | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | M | 34 | 6 | 4 | 1.7 | 6 | 5 | 7.37 | 21.6 | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | M | 40 | 10 | 7 | 3.7 | 4 | 8 | 7.35 | 21.4 | No | TTM | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | M | 21 | 5 | 3 | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 7.09 | 15.9 | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 12 | M | 48 | 11 | 8 | 3.0 | 7 | 5 | 7.27 | 19.6 | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 13 | M | 59 | 11 | 8 | 2.9 | 5 | 9 | – | – | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

| 14 | M | 17 | 4 | 3 | 1.4 | 3 | 10 | – | – | No | No | 2 | Lived | 1 | 2 |

Bicarb.: arterial bicarbonate (mmol L–1); CPC: cerebral performance category; CT HIE: computed tomography evidence of hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy; ED GCS: Emergency Department Glasgow coma score; LOS: length of stay (days); N/A: not applicable; PH GCS: pre-hospital Glasgow coma score; Pred. Mort.: predicted mortality (percentage); Sex (M: male, F: female), Temp. Man.: temperature management (TH: therapeutic hypothermia, TTM: targeted temperature management); Pred. Mort.: predicted mortality; –: unrecorded.

All 14 survived their ICU admission, with 11 having a discharge CPC of one, and three having a poor neurological outcome (CPC of 3). Those with a poor neurological outcome had an ED GCS of five, seven and unrecorded. Median ICU LOS was 2.9 days (1.2–3.8). Presenting GCS was 5.50 ((4.7–8.3), with 4/14 unrecorded). Mean arterial pH was 7.28 ((7.16–7.37), 2/11 unrecorded). Two patients developed seizures whilst on ICU, both surviving with a good neurological outcome. All non-CPR patients had a CT head, with three showing signs of HIE and one secondary traumatic subdural haematoma (SDH). Again, there were no radiologically confirmed cervical spine fractures. No EEG or MRI was performed in this group. TTM was used for two patients, the others receiving no active temperature interventions.

Discussion

Intensive care outcomes from UK victims of hanging have not previously been reported, nor have the proportion of those presenting to ICU after hanging going on to donate including their clinical presentations. Worldwide outcomes after CPR from hanging-related cardiac arrest are variable (4–46% mortality).4,8 Our rates of neurologically intact survival after CPR are, at first glance, favourable compared to Kim et al.’s survival (3/19 (16%) versus 5/121 (4%), respectively). However, this positive comparison should not be overstated. First, this is likely due to our definition of post arrest as anyone with a history of CPR in the previous 24 h. Second, our cohort includes only those who survived to ICU admission, introducing some survival bias. Finally, our group sizes remain small, and statistical significance of this difference was not assessed due to difference in population composition. In the non-CPR group, our rates of good outcome (CPC 1–2) appear less reassuring; 13/14 (79%) versus Kim’s 12/159 (92%), respectively.

There appears to be a global trend towards use of temperature management in patients with a history of cardiac arrest after hanging, but also in those without history of cardiac arrest. There do not appear to be any randomised controlled trials to confirm or refute its effectiveness in either population. Lee et al. describe a short case series with poor outcomes both with and without TH, but in a cohort with generally poor neurological outcomes.9 Sadaka et al. had a single patient case report with good neurological outcome after TH.10 Baldursdottir et al. describe a case series where temperature management was used, with high rates of neurologically intact survival (in asphyxia group, including hangings).11 Borgquist and Friberg report a series from Sweden in a retrospective observational review, with mixed results (14 pts, good outcome in 6/8 with TH, 3/5 without TH, three post-CPR, one intact survivor).7 In our cohort, temperature management was used in 16/18 patients after cardiac arrest. Two of the non-CPR group received TTM without a history of cardiac arrest, presenting opportunities for standardisation. Use of TTM is controversial, with a lack of guidelines and non-observational evidence for its use. With high rates of good neurological outcome of the norm in the absence of CPR, even without temperature therapies, the benefit of TTM may be limited in this population. It is worth noting that TH gave way to TTM during the period of our service evaluation.

There was comprehensive CT imaging of head and neck. As an isolated finding, presence of HIE on CT should not be used to predict neurological outcome, with two of the three post-CPR survivors having positive CT head and having a good neurological outcome. Three non-CPR patients had a CT head suggesting HIE, with two having a good neurological outcome (CPC 1) and one poor (CPC 3). One patient had a secondary SDH, with poor outcome (CPC 3).

We had high rates of cervical spine imaging, with universally normal findings. This compares favourably with Boots et al. who report a low rate of cervical spine radiology (66%), with nine positive findings in 161 patients.8 However, an observational study by Salim et al. described a cohort of 63 US hangings presenting to a trauma centre without a history of arrest or CPR.12 Of these, 19% had injuries on CT, including 5% having cervical spine fractures. This suggests that our high rate of spinal CT is warranted. Data on non-cervical spine CT were not collected during this review, and this question should be looked at in future reviews.

Predicting outcome in suspected DBI, and hence in which cases to withdraw, is notoriously difficult. The 2010 European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines recognised this and described utility of various methods of predicting poor outcome. However, whilst the utility of SSEP and EEG was presented, no formal recommendation for implementation was made.13 In 2015, there were two consensus statements released. Souter et al. released a consensus document advising repeated clinical examination over a suggested period of 72 h as the best way of assessing prognosis, in the absence of validated scoring systems.3 In this case series, 11 patients had organ support withdrawn, including four with acknowledged brain stem death. The time from hanging to withdrawal was not collected in this review, but ICU LOS is likely to be a reasonable surrogate, given that retrieval phase and pre-ICU care are not included, and in ICU patients in whom donation is being considered, the average time from withdrawing organ support to death is 26 min.14 In the seven ‘non-brain stem’ patients in whom withdrawal occurred, the average LOS was 3.8 days. Four of these became donors and three did not (LOS 3.5 and 4.2 days). This suggests that sufficient time for observation was occurring prior to withdrawal. The ERC released updated guidance in December 2015 formalising the use of CT, MRI, SSEP and EEG with clinical findings to define a suggested prognostication statergy.15 SSEP was introduced in response, but was limited in availability due to staffing. Three cases with a history of CPR presented after this date and had life-sustaining treatment withdrawn. One had a LOS of 6.7 and had two CT heads and a non-diagnostic EEG and SSEP. The second had an ITU LOS of 2.9 days, had one CT with HIE but no EEG/SSEP. The third was this patient was of indeterminate prognosis, was observed and discharged after 16.2 days. Clinical parameters (i.e. pupillary and corneal reflexes) were not collected. To demonstrate full compliance with the current ERC guidance, future reviews should routinely include these data.

In our series, organ donation was relatively common outcome (6/19 admissions in the post-CPR group). The 72-h observation period allows assessment of recovery trajectory and optimum chance of both survival and donation, but at the expense of ICU resources.3 The fact that 6 of the 19 went on to donate a total of 18 solid organs suggests that this is justified in facilitating a patients wish to donate. Given that lifetime cost savings per kidney (versus dialysis) are between £47,000 and £170,000, it is also likely to be a cost-effective intervention.16 Finally, it is worth noting that the law surrounding organ donation in Wales changed in December 2015 (shortly before the end of our study) to a system of presumed consent. The impact of this change on consent rates is still being assessed.

It is notable that of the 12 patients where a donor consent process was begun, six families declined to proceed. Given the young age of our hanging victims, previous good health, the suddenness of onset of critical illness, the psychosocial implications of suicide and their previous good health, this may not be surprising. However, it is well below the overall rate reported by NHS Blood and Transplant (74% for all donors, 82% for donors after hanging).6

According to internal audit records, no thoracic organs were donated from our population, due to co-morbidities and poor organ function at the time of offering. Thoracic organs can be used with similar outcomes to those organs from non-hanging patients.17 Our adherence to organ optimisation strategies was not investigated in this review. The care of the potential donor is protocolised and supervised by specialist nurses in organ donation in liaison with transplant surgeons, so assessing adherence to an optimisation strategy may be helpful in demonstrating provision of best practice.

Identified weaknesses

Direct comparison between case series is difficult due to differences in study setting, population characteristics and definitions of neurological outcome. The most recently published series, Kim et al. report on patients presenting to an ED rather than those admitted to ICU.4 This may have resulted in survival bias in our analysis. Earlier case series will report from periods where there are important variations in ICU management, particularly around neuro-protective interventions. For a single centre study, our numbers are relatively high (others report case series of 13, 15 and 25 patients), however, it does give small group sizes for comparison.9,11,7 The nature of this service evaluation is a description of presentations and evaluation of management. Whilst these outcome data may be helpful to inform a general discussion of outcomes in populations with and without CPR, in the absence of statistical analysis of predictors of mortality or CPC, it cannot be used for individual prognostication.

During the case series, there were important changes in optimal management and legal context, including prognostication in DBI, temperature interventions and presumed consent. Future evaluations should include data on prognostication, such as time period of observation and adherence to ERC guidelines.

Conclusion

Outcomes from hanging after a confirmed cardiac arrest are poor, in keeping with existing international data, even in those surviving to ICU admission, and this should guide discussions with family members. Whilst low absolute numbers prevent an assessment of factors related to poor outcome beyond presence of CPR, it is notable that all post-CPR patients with seizure activity died. However, prognostication should follow the ERC 2015 guidance.15 Given all patients with a confirmed cardiac arrest died, and temperature interventions were not used in any of the non-CPR group, this service evaluation can offer little clarity regarding the utility of temperature manipulation after hanging in the absence of CPR. High rates of CT imaging were noted, but extra-axial imaging may be warranted. Donation rates were high compared to a general ICU admission, but consent rates did not reflect those in general or specifically after hanging.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Jason Walker, Consultant Anaesthetist, Ysbyty Gwynedd, Bangor, UK for advice on applicability of statistics. All work was performed at General Intensive Care Unit, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, UK.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Geulayov G, Kapur N, Turnbull P, et al. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self harm in three centres in England, 2000-2012: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self harm in England. BMJ Open 2016; 29: e010538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of National Statistics. Suicides in the UK: 2015 registrations. Report, Office of National Statistics, UK, December 2016.

- 3.Souter MJ, Blissitt PA, Blosser S, et al. Recommendations for the critical care management of devastating brain injury: prognostication, psychosocial, and ethical management: a position statement for healthcare professionals from the neurocritical care society. Neurocrit Care 2015; 23: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim MJ, Yoon YS, Park JM, et al. Neurologic outcome of comatose survivors after hanging: a retrospective multicenter study. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34: 1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation. Preventing suicide; a global imperative. Report, World Health Organisation, Geneva, 2014.

- 6.Neuberger J, Watson C and Hulme W. Use of organs from donors with higher risk. Report, NHS Blood and Transplant, UK, October 2014.

- 7.Borgquist O, Friberg H. Therapeutic hypothermia for comatose survivors after near-hanging – a retrospective analysis. Resuscitation 2009; 80: 210–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boots RJ, Joyce C, Mullany DV, et al. Near-hanging as presenting to hospitals in Queensland: recommendations for practice. Anaesth Intensive Care 2006; 34: 736–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee BK, Jeung KW, Lee HY, et al. Outcomes of therapeutic hypothermia in unconscious patients after near-hanging. Emerg Med J 2012; 29: 748–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadaka F, Wood MP, Cox M. Therapeutic hypothermia for a comatose survivor of near-hanging. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30: 251 e1–e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldursdottir S, Sigvaldason K, Karason S, et al. Induced hypothermia in comatose survivors of asphyxia: a case series of 14 consecutive cases. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010; 54: 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salim A, Martin M, Sangthong B, et al. Near-hanging injuries: a 10-year experience. Injury 2006; 37: 435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 2010; 81: 1305–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston R. The length of the donation process – the data [Online]. http://odt.nhs.uk/pps/Length_donation_process_data_2017.pptx (2017, accessed 21 August 2017).

- 15.Nolan JP, Soar J, Cariou A, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines for post-resuscitation care 2015: section 5 of the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for resuscitation 2015. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41: 2039–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Organ donation taskforce. Organs for transplant: the supplement report. Report, Department of Health, UK, January 2008.

- 17.Mohite PN, Patil NP, Sabashnikov A, et al. ‘Hanging donors’: are we still skeptical about the lungs? Transplant Proc 2015; 47: 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]