Abstract

Decision-making by intensivists around accepting patients to intensive care units is a complex area, with often high-stakes, difficult, emotive decisions being made with limited patient information, high uncertainty about outcomes and extreme pressure to make these decisions quickly. This is exacerbated by a lack of clear guidelines to help guide this difficult decision-making process, with the onus largely relying on clinical experience and judgement. In addition to uncertainty compounding decision-making at the individual clinical level, it is further complicated at the multi-speciality level for the senior doctors and surgeons referring to intensive care units. This is a systematic review of the existing literature about this decision-making process and the factors that help guide these decisions on both sides of the intensive care unit admission dilemma. We found many studies exist assessing the patient factors correlated with intensive care unit admission decisions. Analysing these together suggests that factors consistently found to be correlated with a decision to admit or refuse a patient from intensive care unit are bed availability, severity of illness, initial ward or team referred from, patient choice, do not resuscitate status, age and functional baseline. Less research has been done on the decision-making process itself and the factors that are important to the accepting intensivists; however, similar themes are seen. Even less research exists on referral decision and demonstrates that in addition to the factors correlated with intensive care unit admission decisions, other wider variables are considered by the referring non-intensivists. No studies are available that investigate the decision-making process in referring non-intensivists or the mismatch of processes and pressure between the two sides of the intensive care unit referral dilemma.

Keywords: Decision-making, intensive care units, admission, referral

Background

Intensive care units (ICUs) are specially staffed and equipped, separate and self-contained areas of a hospital dedicated to the management of patients with life-threatening conditions. They provide dedicated facilities for the support and monitoring of vital physiological functions and use the specialist knowledge and skills of medical, nursing and other personnel experienced in the management of these problems. These units are widely recognised to reduce mortality rates in critical illness and do so in a cost-effective manner.1,2 However, the number of beds is a limited resource, with far more referrals made than available bed numbers. This problem is only expected to worsen over the coming years with the rise in demand for intensive care bed days estimated to likely be in the order of 4% per annum.3 It is also acknowledged that not all patients benefit from admission to the ICU, with evidence that certain patient factors (e.g., comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and end-stage liver cirrhosis, and conditions such as multi-organ failure) are associated with better or worse outcomes from referral to ICUs than others.3

With this mismatch of supply and demand, it is the job of senior intensivists to decide how to allocate this resource. These are often high-stakes, difficult, emotive decisions being made with limited patient information, high uncertainty about outcomes and extreme pressure to make these decisions quickly. This is exacerbated by a lack of clear guidelines to help guide this difficult decision-making process, with the onus largely relying on clinical experience and judgement. A recent report by a task force of the world federation of societies of intensivists that explored issues of triage and guidelines stated that ‘Although algorithms can be useful they can never supplant the role of skilled intensivists’.4 However, a lack of guidelines, when working in ambiguous, pressurised and risky contexts, can derail decision-making due to the tendency to rely on psychological biases and faulty heuristics that override more rational processing. For example, using ‘representative heuristics’ to label a patient as ‘unlikely to do well’ on ICU based on prototypical knowledge about that patient type, instead of more rational consideration of the specific qualities of that patient, an issue that is often exacerbated by time pressure to make these decisions quickly.

This uncertainty, compounding decision-making at the individual clinical level, is further complicated at the multi-speciality level for the senior doctors and surgeons referring to ICUs. The lack of consensus around what constitutes an intensive care patient at the unit level can risk further ambiguity for those referring to the unit. Furthermore, these decisions mirror the challenges of those faced by intensivists, also being; difficult, high-stakes, emotive decisions made with lack of time and often without a full understanding of what intensive care can offer these patients. This decision also lacks any clear guidelines or algorithms to help guide it.

This is a systematic review of the existing literature about this decision-making process and the factors that help guide these decisions on both sides of the ICU admission dilemma.

Method

PubMed literature search

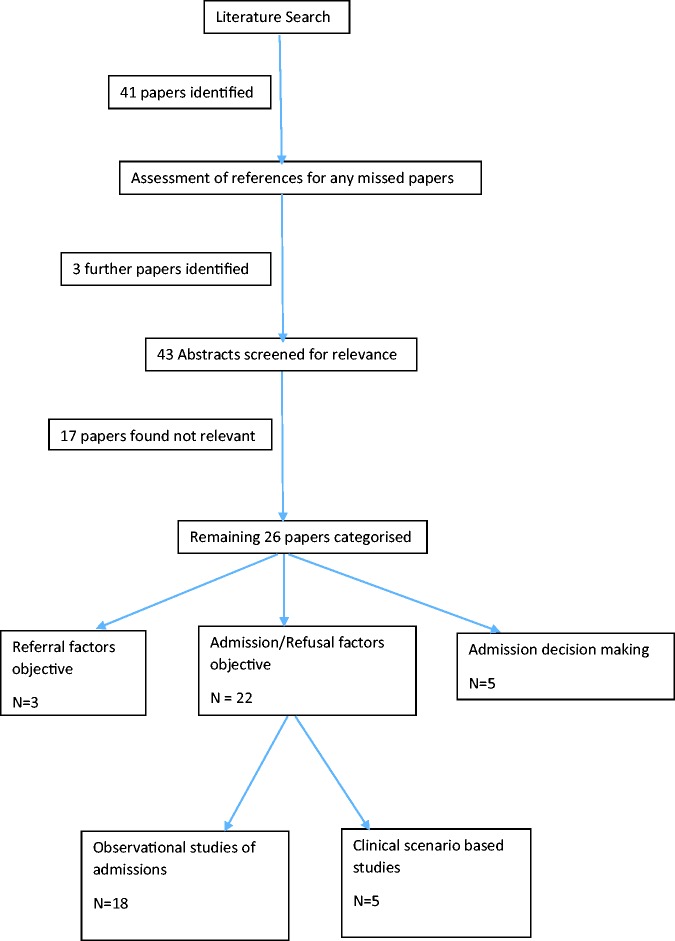

Terms: ‘intensive care unit’, ‘referral’, ‘admission’, ‘accepting’, ‘refusal’. Forty-one papers were identified and a further three identified from manual searching of references. Abstract assessment for relevance led to 17 papers being discarded as not relevant due to being either not primary research or due to studying intensive care factors not to do with admission or referral factors. Further content analysis of the remaining 26 papers led to them being allocated into four categories:

Objective factors correlated with admission decisions by intensivists

Factors identified in clinical scenario-based studies investigated intensive care decision-making

Qualitative investigation of decision-making in ICU admission decisions by intensivists

Factors identified in referring to ICU decision-making by non-intensivists

Papers were analysed and results presented within these categories, with some papers fulfilling criteria to be analysed under multiple categories (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systematic literature search methodology.

Results

Objective factors correlated with admission decisions by intensivists

From the 18 observational prospective studies analysing factors that correlated with ICU admission or rejection, some common themes were seen (see Table 1 for a breakdown of these studies).

Table 1.

Observational prospective studies analysing factors associated with ICU admission or rejection.

| Paper | Type of research | Study population | Aims | Outcomes | Limitations | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Prospective, observational cohort study of lung cancer inpatients with organ failure | 140 Lung cancer patients with organ failure | To investigate factors associated with ITU admission in this population | Factors independently associated with ICU referral were performance status, nonprogressive malignancy and no explicit refusal of ICU admission by the patient and/or family. Factors independently associated with ICU admission were the initial ward being other than the lung cancer unit and an available medical ICU bed. | Referral and admission criteria objective | |

| 6 | A single-centre, prospective, observational study was conducted among consecutive patients in whom an evaluation for ICU admission was requested during times of ICU overcrowding | 95 Patients were evaluated for possible ICU admission during the study period | To investigate characteristics of patients accepted and declined for ITU admission in periods of overcrowding | Triage decisions were not related to the number of available beds in ICU, age or gender. A linear correlation was observed between severity of illness, expressed by APACHE-II scores and the likelihood of being admitted to ICU | American | Admission criteria objective |

| 7 | A single-centre, prospective, observational study of 165 consecutive triage evaluations | 165 Consecutive triage evaluations | To assess factor in admission to ITU | Age, gender and number of ICU beds available at the time of evaluation were not associated with triage decisions | Admission criteria objective | |

| 8 | Observational simulation study of physician decisions in patients’ admissions | 100 Physicians given simulated patient cases | To assess decision making in admitting patients to ITU | Low agreement in decision-making, varies greatly for bed space availability and patient choices | Admission criteria objective | |

| 9 | A single-centre, prospective, observational study of 572 consultations for ITU admission and decisions | 572 ITU admission consultations were recorded | To assess the main factors in the decision to admit to ITU | Patients were less likely to be admitted if their functional baseline was poor and if a DNR was in place. Patients’ age, insurance, ethnicity, severity of illness, presence of malignancy or whether patient’s primary physician was on staff were not independently associated with admission | American, single centre | Admission criteria objective |

| 10 | An observational, prospective study over a six-month period of all adult patients triaged for admission to a medical ICU | 398 Patients requested for ITU admission were assessed | To assess the factors associated with decisions to admit to ITU | Refusal of ICU admission was correlated with the severity of acute illness, lack of ICU beds and reasons for admission request | Morrocan, single centre | Admission criteria objective |

| 11 | Observational, prospective single-centre study of 100 referral to ITU decisions | 100 Patients referred for ITU admission were assessed | To assess factors associated with decisions to admit to ITU and outcomes in those admitted versus not | Patients most likely to receive triage decisions were medical inpatients who had expressed wishes about end-of-life care, who were functionally limited with comorbid conditions or referred by junior doctor. Age, gender, race, diagnostic category, bed status and reason for referral did not impact on admission or triage decisions | Single centre | Admission criteria objective |

| 12 | Observational, prospective, multinational, multicentre study | 8616 Patients referred for ITU admission were assessed | To assess factors associated with decisions to admit to ITU and outcomes in those admitted versus not | Variables positively associated with probability of being admitted to ICU included ventilators in ward; bed availability; Karnofsky score; absence of comorbidity; presence of haematological malignancy; emergency surgery and elective surgery (versus medical treatment); trauma, vascular involvement and liver involvement and acute physiological score II | Admission criteria objective | |

| 13 | Cohort prospective study in a tertiary hospital | 359 Patients referred for ITU admission were assessed | To assess factors associated with decisions to admit to ITU and outcomes in those admitted vs. not | Age, score system and organ dysfunctions were greater in priority groups 3 and 4, and these were related with refusal from the ICU | Admission criteria objective | |

| 14 | Observational, prospective, single-centre study | 250 Patients classified as triage priority 3 when referred for ITU admission were assessed | To identify factors associated with the triage decision for patients classified as Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) Triage Priority 3 | For triage 3 priority patients, medical patients were more likely to be rejected than surgical or neurosurgical patients. Those with a poorer physician-predicted chance of long-term survival were more likely to be rejected than those with a better predicted prognosis | Single centre | Admission criteria objective |

| 15 | Prospective, observational, single-centre study of factors influencing decisions in ITU admission | Data were collected on 179 patients referred for ITU admission | To assess factors associated with decisions to admit to ITU | The only factor that influenced MICU admission was the presence of DNR order. There was no difference between the age, APACHE II scores or functional status between admitted or refused | Admission criteria objective | |

| 16 | Prospective, observational study in the medical ICU in a tertiary nonuniversity hospital | Cohort of 180 patients aged 80 years or over who were triaged for admission to ITU | To assess factors relating to admission to ITU in patients aged over 80 referred | Factors independently associated with refusal were nonsurgical status, age older than 85 years and full unit | Admission criteria objective age | |

| 17 | Prospective, observational study of admission decisions for patients referred for ITU admission | 356 Patients referred for ITU admission in University Hospital of the West Indies | To assess factors relating to admission to ITU in patients referred | The APACHE II score was the strongest predictor of ICU admission, with admission more likely as the score decreased. Of 311 requests considered suitable for admission, 26 (8%) were refused admission due to resource limitations | West Indies, single centre | Admission criteria objective |

| 18 | Observational, prospective, multiple-centre study | To identify factors associated with granting or refusing ICU admission | 574 Patients from four university hospitals and seven primary-care hospitals in France | The reasons for refusal were too-well-to-benefit, too-sick-to-benefit, unit too busy and refusal by the family. Two patient-related factors were associated with ICU refusal: dependency and metastatic cancer. Other risk factors were organizational, namely, full unit, phone admission and daytime admission | French | Admission criteria objective and reasons given |

| 19 | National questionnaire survey using eight clinical vignettes involving hypothetical patients | To assess what factors influence doctors’ decisions about admission to ICU | 232 Swiss doctors specialising in intensive care | Most rated as important or very important the prognosis of the underlying disease and of the acute illness and the patients’ wishes. Few considered important the socioeconomic circumstances of the patients’ religious beliefs and emotional state. In the vignettes factors associated with admission were patients’ wishes, ‘upbeat’ personality, younger age and a greater number of beds | Admission criteria objective and subjective | |

| 20 | Prospective, observational study to assess factors influencing admission decisions, single-centre study | To assess the appropriateness of ICU triage decisions | 334 patient admission decisions were assessed | Reasons for refusal were being too-sick-to-benefit and too-well-to-benefit. Factors independently associated with refusal were patient location, ICU physician seniority, bed availability, patient age, underlying diseases and disability | Single centre | Admission criteria objective and reasons given |

| 21 | Prospective, descriptive evaluation in a multi-disciplinary ICU, university referral hospital | To evaluate factors associated with decisions to refuse ICU admission | 624 patient admission decisions were assessed | Refusal was associated with older age, diagnostic group and severity of illness | Single centre | Refusal criteria objective |

| 22 | Prospective, descriptive, single-centre study | To assess physician decision-making in triage for intensive care | 382 patient admission decisions were assessed | Intensive care admission correlated with APACHE II score, age, a full unit, surgical status and diagnoses | Single centre | admission criteria objective |

DNR: do not resuscitate; ICU: intensive care unit; MICU: medical intensive care unit; ITU: intensive therapy unit.

Factors identified as important varied between studies. The most commonly identified factors were bed availability (n = 8), severity (normally as quantified by APACHE-II score) (n = 10) and the initial ward or team that the patient was referred from (n = 8). However, there was some discordance with a couple of studies identifying that there was no association between bed availability. Other factors identified as associated with ICU admission were do not resuscitate (DNR) status, patient choice, functional baseline, level of referring doctor, level of accepting doctor, a history of active cancer, and admission during daytime hours. The main factor not identified as not associated with ICU admission or rejection was gender (n = 4). Age was an interesting factor with equal number of studies finding an association (n = 4), with higher age being associated with higher levels of ICU rejection, and finding no association (n = 4). See Table 2 for the breakdown of associated factors.

Table 2.

Factors associated with ICU admission or rejection.

| Factor | Studies that identified an association between factor and ITU acceptance/rejection | Studies that identified no association between factor and ITU acceptance/rejection |

|---|---|---|

| Severity | 10 | 2 |

| Bed availability | 8 | 2 |

| Initial ward/team | 8 | 0 |

| Functional baseline | 4 | 1 |

| Age | 4 | 4 |

| Patient choice | 4 | 0 |

| DNR status | 3 | 0 |

| Level of referring doctor | 1 | 0 |

| Level of accepting doctor | 1 | 0 |

| Active cancer | 0 | 1 |

| Day time admission | 1 | 0 |

| Gender | 0 | 4 |

DNR: do not resuscitate; ITU: intensive therapy unit.

Factors identified in clinical scenario-based studies investigated intensive care decision-making

Five studies investigated intensive care decision-making using clinical vignette scenario-based studies (see Table 3 for a breakdown of these studies).

Table 3.

Clinical vignette based studies of ICU decision making.

| Paper | Type of research | Study population | Aims | Outcomes | Limitations | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Vignette-based questionnaire survey to intensivists and non-intensivists | 21 intensivists and 22 internists completed five vignettes | Opinions over benefit of ICU admissions of critically ill medical inpatients differed based on physician specialty, namely intensivists and internists | Physician specialty base did not affect assessments of ICU admission benefit or accuracy in outcome prediction but resulted in a statistically significant difference in level of care assignments. A significant disagreement amongst individuals in each group was found | Canadian, small sample, single centre, ?clear cut vignettes | Scenario-based study |

| 8 | Observational, simulation study of physician decisions in patients’ admissions | 100 physicians given simulated patient cases | To assess decision-making in admitting patients to ITU | Low agreement in decision-making, varies greatly for bed space availability and patient choices | Scenario-based study | |

| 24 | Scenario-based survey of differences between Australian CrCU doctors and New Zealand CrCU doctors | Scenario-based survey of 238 Australian/New Zealand doctors | To assess differences in admission policies | New Zealand doctors have more selective views of what constitutes an appropriate admission to intensive care. But views vary massively within each group | Australian/New Zealand no generalised applicability | Scenario-based study |

| 19 | National questionnaire survey using eight clinical vignettes involving hypothetical patients | To assess what factors influence doctors’ decisions about admission to intensive care | 232 Swiss doctors specialising in intensive care | In the vignettes factors associated with admission were patients’ wishes, ‘upbeat’ personality, younger age and a greater number of beds. Correlations between decisions on admission were very weak | Swiss | Decision-making in admission, scenario-based study |

| 25 | Hypothetical case scenario-based questionnaire | To assess the importance of age as a factor in admission decisions | When age was the only difference between two patients in a hypothetical case scenario, 80.7% of respondents chose the younger patient (age 56 years) for admission and 13.2% chose the older patient (age 82 years). Following the provision of more detailed medical and social information, however, only 53.5% chose the younger patient and 41.2% chose the older patient. | Decision-making in admission, scenario-based study |

CrCU: critical care unit; DNR: do not resuscitate; ITU: intensive therapy unit.

Two of these used general scenarios to a population of intensivists to identify important factors. These studies identified similar factors to the above category of studies, including age, bed space and patient choice. Interestingly, the most important finding in each of these studies was the low agreement in decision-making amongst the intensivists, with very weak correlations between decisions to admit.

One of the studies used scenarios to assess the difference in admitting decisions between Australian and New Zealand intensivists. Although it did find that New Zealand intensivists had more selective views of what constitutes an appropriate admission to intensive care, it also found that views vary massively within each group.

One study used a scenario-based design to assess decision-making around patient age and ICU admission decisions. When the vignette differed only by age of the patient, the vast majority picked to admit the younger patient; however, following the provision of more detailed medical and social information skewed in the favour of the older patient, this levelled out to half the participants picking the younger patient. This study again showed big differences in the decisions made between intensivists within the group of intensivists making decisions.

The final scenario-based study aimed to investigate the differences in opinion over the benefit of ICU admission from intensivists and non-intensivists. They found that there was no difference in assessments of ICU admission benefit between intensivists and non-intensivists; however, a statistically significant difference in levels of care assignments, such as treatment limitations and DNCPR decisions, was found between them. Again the most striking finding was the significant disagreement amongst individuals in each group regarding admission decisions.

Qualitative investigation of decision-making in ICU admission decisions by intensivists

Five studies investigated the decision-making process by use of surveys or interviews (see Table 4 for a breakdown of these studies).

Table 4.

Survey or interview based studies of ICU decision making.

| Paper | Type of research | Study population | Aims | Outcomes | Limitations | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | Combined observation and interviews with critical care physicians | 30 Critical care doctors managing 71 referrals and conducted 10 interviews with senior decision-makers in a UK hospital | Explore the themes in accepting intensivists’ decision-making | Patient, physician and contextual factors strongly shaped the decision to transfer the patient to critical care. There were no absolute patient indications or contraindications for transfer to critical care. Instead, sets of relative indications and contraindications for admission were ‘summed’, with the overall balance swaying the eventual outcome | Qualitative research | Accepting admission decision-making |

| 27 | Survey-based study of ITU doctors in 20 ITUs in Milan | 225 Doctors from 20 ITUs in Milan responded to the survey | To assess physicians’ perceptions and attitudes regarding inappropriate admissions and resource allocation in the intensive care setting | Inappropriate admissions were acknowledged by 86% of respondents. The reasons given were clinical doubt (33%); limited decision time (32%); assessment error (25%); pressure from superiors (13%), referring clinician (11%) or family (5%); threat of legal action (5%) and an economically advantageous ‘Diagnosis Related Group’ (1%) | Italian | Decision-making admission |

| 19 | National questionnaire survey using eight clinical vignettes involving hypothetical patients | To assess what factors influence doctors’ decisions about admission to intensive care | 232 Swiss doctors specialising in intensive care | Most rated as important or very important the prognosis of the underlying disease and of the acute illness and the patients’ wishes. Few considered important the socioeconomic circumstances of the patients’ religious beliefs and emotional state | Admission criteria objective and subjective | |

| 25 | Hypothetical case scenario-based questionnaire | To assess the importance of age as a factor in admission decisions | In a ranking of several admission factors, age was found to be of less importance than severity of presenting illness, previous medical history and DNR status but of more importance than patient motivation, ability to contribute to society, family support and ability to pay for care | Age questionnaire |

DNR: do not resuscitate; ITU: intensive therapy unit.

The use of ranking importance of factors highlighted the importance of many of the factors identified by objective correlation of factors in decision-making or real cases such as severity of illness, patient wishes, DNR status, age and bed availability. A new factor was also identified as playing a role in admission decision-making which was not shown in the objective factor correlation studies – patient’s personality, with an ‘upbeat’ patient personality favouring a decision to admit to ICU.

One study using a survey to investigate intensivists’ perceptions and attitudes regarding inappropriate admissions and resource allocation found that the vast majority admitted to having made inappropriate admission decisions. The reasons behind these included clinical doubt, limited decision time, assessment error, pressure from superiors or referring clinician or family, threat of legal action and in economically advantageous patient groups.

One study used an ethnographic approach of combined observation and interviews to qualitatively investigate the decision-making process and concluded that patient, physician and contextual factors strongly shaped the decision to transfer the patient to intensive care. There were no absolute patient indications or contraindications for transfer to intensive care. Instead, sets of relative indications and contraindications for admission were ‘summed’, with the overall balance swaying the eventual outcome. It also identified a very experientially led decision-making process.

Factors identified in referring to ICU decision-making by non-intensivists

Only three studies investigated decision-making by the referring non-intensivists (see Table 5 for the breakdown of these studies).

Table 5.

Studies investigating decision making by referring non intensivists.

| Paper | Type of research | Study population | Aims | Outcomes | Limitations | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Vignette-based questionnaire survey to intensivists and non-intensivists | 21 Intensivists and 22 internists completed five vignettes | Opinions over benefit of ICU admissions of critically ill medical inpatients differed based on physician specialty, namely intensivists and internists | Physician specialty base did not affect assessments of ICU admission benefit or accuracy in outcome prediction but resulted in a statistically significant difference in level of care assignments. A significant disagreement amongst individuals in each group was found | Canadian, small sample, single centre, ?clear cut vignettes | Referring and accepting |

| 5 | Prospective, observational cohort study of lung cancer inpatients with organ failure | 140 Lung cancer patients with organ failure | To investigate factors associated with ITU admission in this population | Factors independently associated with ICU referral were performance status, nonprogressive malignancy and no explicit refusal of ICU admission by the patient and/or family. Factors independently associated with ICU admission were the initial ward being other than the lung cancer unit and an available medical ICU bed | Referral and admission criteria objective | |

| 28 | Prospective, observational cohort study of patients aged ≥80 years who were triaged in the emergency room, with at least one independent criteria suggesting ITU admission could be useful | Decisions for ITU admission for a total of 2646 Patients aged ≥80 years with at least one criterion in French hospitals | To describe ICU referral decisions by emergency room physicians in patients aged ≥80 years | Factors associated independently with no ICU referral were age, active cancer, unknown hospitalization status, unknown living arrangements, regular psychotropic medications, low severity, low activity in daily living score, emergency and ICU physicians were extremely reluctant to consider ICU admission of patients aged >80 years, despite the presence of criteria indicating that ICU admission was certainly appropriate. | French | Referral admission criteria objective, age |

DNR: do not resuscitate; ICU: intensive care unit; ITU: intensive therapy unit.

One of these studies looked at factors associated with ICU referral. Some of these factors match those identified in factors associated with ICU admission, such as age, severity of illness and functional baseline. Some factors were seen to influence referral decision-making which have not been identified in the studies investigating accepting decision-making, such as active cancer status, unknown living arrangements and regular psychotropic medication use, all of which were correlated with a decision not to refer the patient to ICU.

One, which has already discussed in the scenario-based study section, showed that there was no difference in assessments of ICU admission benefit or accuracy in outcome prediction between intensivists and non-intensivists, but there was a statistically significant difference in level of care assignments. A significant disagreement amongst individuals in each group was found.

One study investigated the difference in factors correlated with both ICU referral and admission in a specific subpopulation of patients – those with lung cancer. They found that factors associated with ICU acceptance were similar to those outlined in the above for the general patient population of: bed space and initial ward they were referred from. Interestingly, here the most important factor for admission acceptance was being from a ward other than the lung cancer ward. Factors correlated with ICU referral were performance status, nonprogressive malignancy and no explicit refusal of ICU admission by the patient and/or family.

Discussion

This review had analysed many different study designs and approaches investigating decision-making in ICU referral and admission decisions. A wealth of information in the form of many, large, well-designed, prospective, observational studies exists assessing the patient factors that correlated with ICU admission decisions. Analysing these together suggests that the factors consistently found to be correlated with a decision to admit or refuse a patient from ICU are bed availability, severity of illness, initial ward or team referred from, patient choice, DNR status and functional baseline. These factors identified by this study type were also identified using clinical scenario-based studies to investigate factors associated with ICU admission decisions.

Some factors are not surprising including DNR status, patient choice and functional baseline, whilst others may be due to the varying health economics of the studies (for example, limited bed capacity or the severity of illness of patients accepted to a unit).

Age as a factor has been found to be associated with ICU admission decision and not associated with ICU admission decision in equal numbers of studies. Several survey studies done with intensivists themselves have shown that the majority of intensivists think that age is an important factor. Even amongst the dearth of information that exists on decision-making in referring non-intensivists, it has been shown that age is a factor that correlates with the decision to refer to ICU. Further investigation of this complex variable by way of clinical scenarios adjusted by age shows that age is an important variable when all other patient factors are matched, but when further patient information is available in favour of the older patient, it become less important. We suspect that this is because age may be clinically used as a surrogate for comorbidity and frailty.

Much less research has been done on the decision-making process itself and the factors that are important to the accepting intensivists when they make these decisions. The few small studies that exist show that in general the factors which objectively correlate to admission decisions are subjectively considered by intensivists too, with other factors such as patient personality, which may be harder to capture in an observation objective study design. The only study that exists looking qualitatively at the decision-making process by an interview-based study design gives an overview on how these patient factors added to physician and contextual factors to shape the decision to transfer the patient to ICU, with sets of relative indications and contraindications being ‘summed’, with the overall balance swaying the eventual outcome.26 It has also been shown that intensivists are under a lot of pressure during these decisions and that the vast majority are aware of making the wrong decision at times due to external stressors influencing their decision-making such as clinical doubt, limited decision time, assessment error, pressure from superiors or referring clinician or family or threat of legal action.27

Even less research exists on referral decision, with only a small study investigating factors that are correlated with ICU referral and demonstrating that as well as the factors correlated with ICU admission decisions, other wider variables are considered by the referring non-intensivists such as active cancer status, unknown living arrangements and regular psychotropic medication use, perhaps suggesting a more holistic patient assessment.28 No studies are available that investigate decision-making process in referring non-intensivists or the mismatch of processes and pressure between the two sides of the ICU referral dilemma.

Conclusion

Many prospective observational studies and clinical scenario-based studies exist assessing the patient factors correlated with ICU admission decisions. Analysing these together suggests that the factors consistently found to be correlated with a decision to admit or refuse a patient from ICU are bed availability, severity of illness, initial ward or team referred from, patient choice, DNR status, age and functional baseline. There has been very limited investigation of the actual decision-making process and the factors that are important to the accepting intensivists. The few small-scale studies that exist show that in general the factors which objectively correlate to admission decisions are subjectively considered by intensivists too, with other factors such as patient personality, which may be harder to capture in an observation objective study design. Even less research exists on referral decision, with only one small study investigating factors that are correlated with ICU referral and demonstrating that as well as the factors correlated with ICU admission decisions, other wider variables are considered by the referring non-intensivists. No studies are available that investigate decision-making process in referring non-intensivists or the mismatch of processes and pressure between the two sides of the ICU referral dilemma.

Further research should be focussed on factors relating to referral to ICU and how these may differ from those related to ICU admission. In particular, investigating these differences and how they arise from the decision-making process by referring and accepting clinicians may facilitate the referral process and allocation of limited resources in a more efficient manner. We would also recommend further investigation of how the international variation of health economics impacts on clinical decision-making. Finally, it would also be of benefit to analyse the complex factor of age in relation to ICU admission and how it appears to be clinically used as a surrogate for other factors.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Talmor D, Shapiro N, Greenberg D, et al. When is critical care medicine cost-effective? A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness literature. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 2738–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchings A, Durand MA, Grieve R, et al. Evaluation of modernisation of adult critical care services in England: time series and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2009; 339: b4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packham V, Hampshire P. Critical care admission for acute medical patients. Clin Med (Lond) 2015; 15: 388–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanch L, Abillama FF, Amin P, et al. Triage decisions for ICU admission: report from the Task Force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. J Crit Care 2016; 36: 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toffart AC, Pizarro CA, Schwebel C, et al. Selection criteria for intensive care unit referral of lung cancer patients: a pilot study. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orsini J, Blaak C, Yeh A, et al. Triage of patients consulted for ICU admission during times of ICU-bed shortage. J Clin Med Res 2014; 6: 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orsini J, Butala A, Ahmad N, et al. Factors influencing triage decisions in patients referred for ICU admission. J Clin Med Res 2013; 5: 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Tabah A, Vesin A, et al. The ETHICA study (part II): simulation study of determinants and variability of ICU physician decisions in patients aged 80 or over. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen RI, Eichorn A, Silver A. Admission decisions to a medical intensive care unit are based on functional status rather than severity of illness. A single center experience. Minerva Anestesiol 2012; 78: 1226–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louriz M, Abidi K, Akkaoui M, et al. Determinants and outcomes associated with decisions to deny or to delay intensive care unit admission in Morocco. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howe DC. Observational study of admission and triage decisions for patients referred to a regional intensive care unit. Anaesth Intensive Care 2011; 39: 650–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iapichino G, Corbella D, Minelli C, et al. Reasons for refusal of admission to intensive care and impact on mortality. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36: 1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldeira VM, Silva Junior JM, Oliveira AM, et al. Criteria for patient admission to an intensive care unit and related mortality rates. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2010; 56: 528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shum HP, Chan KC, Lau CW, et al. Triage decisions and outcomes for patients with Triage Priority 3 on the Society of Critical Care Medicine scale. Crit Care Resusc 2010; 12: 42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen RI, Lisker GN, Eichorn A, et al. The impact of do-not-resuscitate order on triage decisions to a medical intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2009; 24: 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Montuclard L, et al. Decision-making process, outcome, and 1-year quality of life of octogenarians referred for intensive care unit admission. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32: 1045–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augier R, Hambleton IR, Harding H. Triage decisions and outcome among the critically ill at the University Hospital of the West Indies. West Indian Med J 2005; 54: 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Montuclard L, Timsit JF, et al. Predictors of intensive care unit refusal in French intensive care units: a multiple-center study. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escher M, Perneger TV, Chevrolet JC. National questionnaire survey on what influences doctors’ decisions about admission to intensive care. BMJ 2004; 329: 425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Montuclard L, Timsit JF, et al. Triaging patients to the ICU: a pilot study of factors influencing admission decisions and patient outcomes. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29: 774–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joynt GM, Gomersall CD, Tan P, et al. Prospective evaluation of patients refused admission to an intensive care unit: triage, futility and outcome. Intensive Care Med 2001; 27: 1459–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprung CL, Geber D, Eidelman LA, et al. Evaluation of triage decisions for intensive care admission. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahine J, Mardini L, Jayaraman D. The perceived likelihood of outcome of critical care patients and its impact on triage decisions: a case-based survey of intensivists and internists in a Canadian, quaternary care hospital network. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0149196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young PJ, Arnold R. Intensive care triage in Australia and New Zealand. N Z Med J 2010; 123: 33–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuckton TJ, List ND. Age as a factor in critical care unit admissions. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 1087–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlesworth M, Mort M, Smith AF. An observational study of critical care physicians’ assessment and decision-making practices in response to patient referrals. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giannini A, Consonni D. Physicians’ perceptions and attitudes regarding inappropriate admissions and resource allocation in the intensive care setting. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Boumendil A, Pateron D, et al. Selection of intensive care unit admission criteria for patients aged 80 years and over and compliance of emergency and intensive care unit physicians with the selected criteria: an observational, multicenter, prospective study. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 2919–2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]