Introduction

Historical trauma and unresolved grief are associated with adverse impacts on the health and well-being of American Indians (AI) in the US (M. Yellow Horse Brave Heart and DeBruyn 1998; M. Yellow Horse Brave Heart 1999). Many events contribute to AI historical trauma and unresolved grief such as genocide, loss of land, forced removal from homelands, involuntary relocation to other lands, disease, warfare, colonization, and forced cultural assimilation through compulsory boarding school attendance (Duran et al. 1998; M. Yellow Horse Brave Heart and DeBruyn 1998; Evans-Campbell 2008; M. Yellow Horse Brave Heart et al. 2011). The purpose of AI boarding schools was the assimilation of AI children by removing them from their families and tribal communities. In AI residential boarding schools children were forced to adopt the English language, a non-Native culture and way of life, and Christianity, etc. (Adams 1995; Child 1998). American Indian boarding schools operated on small budgets resulting in malnourishment, inadequate health care, overcrowding, and some students died of disease and starvation (Child 1998; Smith 2007). Accounts of boarding school experiences detail incidents of punishment for use of traditional tribal language, culture, and spirituality, with extensive descriptions of culture shock (Adams 1995; Child 1998). Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse are often reported by AIs attending boarding school (Smith 2004, 2009; Churchill 2004). A prevailing sense of despair, loneliness, and isolation from family and community are often described (Child 1998). Evidence suggests boarding school attendance has lasting negative effects on AIs (Smith 2004, 2007, 2009; Kaspar 2014; Bombay et al. 2014).

An AI specific theoretical model suggests that unresolved historical trauma which includes boarding school experiences and genocide are leading contributors to the chronic disease disparities currently experienced by AIs (Warne 2015). Negative boarding school experiences become part of an individual’s adverse childhood experiences and carry forward to adverse adulthood experiences. Unresolved adult issues are then transferred to offspring creating adverse childhood experiences for the next generation. Moreover, adverse adult experiences such as poverty, poor nutrition, racism, and substance abuse also contribute to poor health outcomes (Warne 2015).

Health care practitioners increasingly recognize the detrimental consequences of the US boarding school experience on AI health (Brasfield 2001; Heckert and Eisenhauer 2014). The term “residential school syndrome” is suggested as a diagnostic term to describe a common etiology experienced by AI survivors of boarding school experiences (Brasfield 2001). The criteria for the diagnosis are similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, but specifically focus on boarding school attendance symptoms. The criteria include persistent and disturbing memories, dreams, feelings, flash backs, etc. of boarding school experiences after attendance ceases. The criteria also consist of avoidance of stimuli related to boarding school and numbing responses not present prior to but evident after attendance. Proposed criteria include but are not limited to parenting deficiencies, substance use disorders, anger, as well as intergenerational impacts (Brasfield 2001).

Studies from Canadian among Aboriginal people report boarding school attendance negatively affects physical health status (Kaspar 2014; Barton et al. 2005). Although the earlier study was small and primarily descriptive it reported those who attending boarding school had worse physical health status than those who did not (Barton et al. 2005). The later, a secondary analysis of cross-sectional national data from the Aboriginal Peoples Survey, found boarding school attenders were more likely to have poorer physical health status than non-attenders (Kaspar 2014). Furthermore, the results pointed to multiple paths to poor health status with socioeconomic status and community adversity mediating the relationship of boarding school attendance and physical health status (Kaspar 2014).

AI boarding school research in the US focuses on the concomitant behavioral health, psychological, and emotional impacts (M. Yellow Horse Brave Heart et al. 2011; Evans-Campbell et al. 2012). The literature is silent regarding the impact of boarding school attendance on the physical health of AIs who reside in the US. Our hypothesis was that boarding school attendance among Northern Plains (NP) tribal members would be associated with lower self-reported physical health status while controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, and health variables. Since an increased number of health conditions is associated with poorer physical health status, we control for the number of mental health disorders and the number of physical health conditions (Lluch-Canut et al. 2013; Ko and Coons 2005).

Methods

Data Source

This secondary analysis drew upon data collected through the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP). AI-SUPERPFP is the largest comprehensive assessment to date of the prevalence of alcohol, drugs, mental disorders and associated service utilization in two AI populations located in distinct geographic locations (Northern Plains and Southwest). AI-SUPERPF included tribally enrolled members, aged 15–54 at the time of sampling, who lived on or within 20 miles of their reservation. Data were acquired by computer-assisted personal interviews between 1997–1999 using stratified random sampling procedures (Anthony et al. 1994).

Once located, 77% agreed to participate. Data were collected by tribal members who received intensive training in research and interview procedures. Prior to initiation of the AI-SUPERPFP, approval was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and tribal governments through tribal resolution. All participants gave informed consent. Detailed descriptions of the AI-SUPERPFP methods are documented elsewhere (Janette Beals et al. 2003; The Regents of the University of Colorado 2015). This analysis focused on the Northern Plains sample (n=1638). The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined the present analyses “not human subject research.” Tribal approvals of these analyses were obtained through tribal research review boards or by tribal resolutions.

Measures

Outcome Measure

The Physical Component Summary Score (PCS) of the SF-36 was the outcome variable and measured participant self-reported physical health status (Ware 1994). The PCS score ranges from 0 to 100 (mean=50 and standard deviation=10) with higher scores indicating better health status. Prior to AI-SUPERPFP data collection, focus groups comprised of tribal members reviewed and adapted the SF-36 for cultural relevance. Several changes were made to the physical functioning questions. For instance, mopping, sweeping, and horseback riding were substituted for pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling or playing golf. Questions that asked about walking block(s) were changed to walking yards, as blocks in the conventional sense do not exist on NP tribal lands. A question that inquired about the limitations of climbing several flights of stairs was changed to climbing a steep hill given that few buildings had flights of stairs. The general health question that asked, “I expect my health to get worse” was deleted. Focus group participants felt the expectation of one’s health worsening contradicted cultural ideology.

Four scales comprise the PCS score and include physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health. The physical functioning scale included 10 questions related to physical limitations in daily activities; role-physical involved 4 measures associated with limitations in work or other activities; bodily pain was comprised of 2 questions related to the intensity of pain experienced and limitations due to pain. General health included 4 questions, one a self-rated question of health from poor to excellent, as well as other questions associated with personal health (Ware 1994). The PCS score was derived using established algorithms and scores were standardized to allow for meaningful comparison to other studies (Ware 1994). Previous analyses using the AI-SUPERPFP sample demonstrated that the PCS performed well among the NP Tribes (Jiang et al. 2009; Mitchell and Beals 2011); Cronbach’s α’s = 0.91. The minor changes to the questions, did not impact the overall scoring of the PCS. Analysis of the psychometric properties of the SF-36 used in these analyses were comparable to previous work with an AI sample (J. Beals et al. 2006).

Primary Independent Variable

Boarding school attendance was our primary independent variable. Attendance was a self-reported (yes=1/no=0) response to the question “Did you ever attend boarding school?”

Other Independent Variables

Demographic variables

Demographic variables were age and gender (female=1/male=0). Age at the time of interview was dichotomized using those aged younger than 21 as the reference group. We use age as a control variable. Those 20 and younger who attended boarding school would have had dissimilar experiences to those 21 and older. This age dichotomy corresponds to a time when tribes in the NPs began to manage and oversee boarding schools instituting changes that produced an educational environment supportive of cultural traditions, language and heritage, and thus is starkly different from environments experienced by older study participants. These changes began in the early 1970s (Indian Education Act of 1972; Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975; Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978; Ziibiwing Center of Anishinable Culture and Lifeways 2011). When the AI-SUPERPFP interviews took place in the late 1990s, participants aged 20 or younger were less likely to have attended boarding school and, for those that did attend, did so in an educational environment quite different from those of older study participants.

Socioeconomic (SES) variables

Socioeconomic (SES) variables were married or cohabitating (living as though married), high school completion or the equivalent, unemployed at the time of the interview, and living in a household below the US Federal poverty level. These were all coded as dichotomous indicators (1=yes/0=no).

Health Variables

Health Variables included the number of DSM-IV disorders and the number of physical health problems experienced within the last year. A culturally adapted version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview assessed the presence of 9 psychiatric disorders using DSM-IV criteria which including: major depressive episode, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence (Andrews and Peters 1998; R. C. Kessler and Ustun 2004; Ronald C. Kessler et al. 1998) (American Psychiatric Association 1994). The number of health problems was a count of 31 common chronic physical health problems diagnosed by a doctor and experienced within past year. These chronic health problems included but were not limited to arthritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, kidney problems, stroke, and high cholesterol, etc.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample: means and standard deviations for continuous variables and number and percent for categorical variables. Linear regression was used to examine the bivariate associations of the physical health status score with each variable. Mean values, 95% confidence intervals, and statistical significance are reported. Individuals who attended boarding school and those who did not were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and x2 tests for categorical variables. Sample weights were used to account for the differential probability of selection into the sample (Cochran 1977).

To test our hypothesis we used Mplus, (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014) estimating nested linear regression models, progressively adding in blocks of variables beginning with the bivariate relationship of boarding school attendance to the physical health status (Model 1). Next we added demographic and SES indicators (Model 2). In examining the health related variables, we first added in the number of DSM-IV disorders (Model 3), followed by the number of physical health problems (Model 4). Improvements in the fit of models were assessed by R-squared and are reported for each model.

Substantial decreases in the magnitude of parameter estimates between Model 3 and Model 4 indicated a potential for mediation with the number physical health problems acting as a mediator. Therefore, we conducted post-hoc mediation analysis using Baron and Kenny (1986) criteria and definitions of full and partial mediation. Full mediation occurs when statistically significant relationships between physical health status (the outcome) and independent variable(s) are no longer statistically significant when the mediating variable (number of physical health problems) is included in the model, while partial mediation occurs when relationships are greatly reduced with the number of health problems in the model (Baron and Kenny 1986). Mediation was tested using path analysis in Mplus and indirect, direct, and total effects for all variables were reported (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014). Throughout, we used full information maximum likelihood, the default method for handling missing data in Mplus, allowing us to retain the entire sample for all nested models (n=1638) (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2014). Only 2% of the data was missing from the data used in these analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the sample appear in Table 1. The average physical health status score was 50.6 (SD=9.4); 48% attended boarding school. Eighty-six percent of the sample was 21 or older; 51% was female; 51% was married/cohabitating; 47% had a high school education or equivalent; 32% was unemployed; and 62% lived below the US federal poverty level. The average number of DSM-IV disorders was .35 (SD=.72); the average number of health problems was 1.6 (SD=2.2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Sample and Bivariate Associations of PCS Score with Covariates

| Entire Sample | PCS Score with Covariates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/mean | %/sd | mean | 95% CI | |

| Physical Component Summary Score | 50.6 | 9.4 | ||

| Attended Boarding School | 786 | 48% | 49.5 | 48.6, 50.5*** |

| Demographics | ||||

| Aged 21+ | 1409 | 86 % | 50.3 | 49.3, 51.2*** |

| Female | 835 | 51% | 49.8 | 48.8, 51.7*** |

| Socioeconomic Variables | ||||

| Married/cohabitating | 835 | 51 % | 50.0 | 49.1, 51.0* |

| High School Graduate or GED | 770 | 47% | 50.7 | 51.4, 51.6 |

| Unemployed | 524 | 32% | 47.9 | 46.8, 49.0*** |

| Below federal poverty level | 1016 | 62% | 50.2 | 49.2, 51.2* |

| Health Variable (past year) | ||||

| Number of DSM-IV disorders | 0.35 | 0.72 | 49.5 | 48.7, 50.2*** |

| Number of health problems | 1.6 | 2.2 | 53.5 | 53.3, 53.6*** |

PCS=Physical Component Summary Score, n=number, sd= standard deviation, %=percent, CI=confidence interval,

pvalue≤.05,

pvalue≤.01,

pvalue≤.001

Table 2 depicts the results of the nested linear regression Models 2–4. Model 1, not shown, is the bivariate association of physical health status and boarding school attendance which indicates those who attended boarding school had lower physical health status scores than those who did not (β= −1.93, z = −3.94, SEM= .49, p <.001, two-tailed). Including demographic and SES variables (Models 2) attenuated the relationship of boarding school and physical health status but the association remained statistically significant. Model 3 generated results similar to the 2 preceding models but also revealed that the number of DSM-IV disorders was associated with a decrease in physical health status. Model 4 indicated controlling for other variables, unemployment and the number of physical health problems were associated with a decrease in physical health status. The results of Model 4 also revealed that variables statistically significant in Model 3 (boarding school, age, gender) were no longer statistically significant when the number of self-reported health problems was included in the model. This suggests that the number of self-reported health problems fully mediated these relationships. Additionally, Model 4 also highlights a marked reduction in the relationship of physical health status to unemployment and the number of DSM-IV disorders compared to Model 3, implying that the number of self-reported health problems partially mediated these relationships.

Table 2.

Nested Linear Regression Models Predicting Physical Health Status with Boarding School as Primary Independent Variable

| Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | 95% CI | Est | SE | 95% CI | Est | SE | 95% CI | |

| Attended Boarding School | −1.38** | .49 | −2.34, −.42 | −1.23** | .49 | −2.19, −.27 | −.39 | .41 | −1.20, .42 |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Aged 21+ | −1.95*** | .54 | −3.02, −.89 | −1.89*** | .54 | −2.94, −.84 | .09 | .50 | −.90, 1.07 |

| Female | −1.38** | .48 | −2.31, −.45 | −1.45** | .47 | −2.38, −.53 | −.40 | .41 | −1.20, .40 |

| Socioeconomic Variables | |||||||||

| Married/cohabitating | −.69 | .49 | −1.65, .27 | −.76 | .49 | −1.71, .19 | −.32 | .42 | −1.14, .50 |

| HS or GED | .42 | .49 | −.54, 1.38 | .26 | .49 | −.69, 1.21 | −0.14 | .42 | −.95, .67 |

| Unemployed | −3.70*** | .58 | −4.84, −2.55 | −3.63*** | .58 | −4.76, −2.49 | −2.29*** | .49 | −3.25, −1.33 |

| Below poverty level | −.13 | .53 | −1.16, .90 | −.05 | .52 | −1.07, .97 | −.01 | .44 | −.87, .84 |

| Health Variables (past year) | |||||||||

| Number DSM-IV disorders | −1.59*** | 0.36 | −2.29, −.89 | −.61* | .31 | −1.21, − .02 | |||

| Number health problems | −2.10*** | .12 | −2.34, −1.87 | ||||||

| R-Squared | .06 | .08 | .31 | ||||||

HS=high school

Table 3 presents results of the path analysis using the number of self-reported health problems as the mediating variable and boarding school as the primary independent variable. The table characterizes the indirect relationship of each variable to physical health status mediated by the number of health problems, the direct relationship of each variable to physical health status, and the combined effects of both the indirect and direct results. The number of self-reported health problems mediated the relationship of boarding school attendance, and also acted as a mediator for age, gender, unemployment, and number of DSM-IV disorders to physical health status (indirect results). The direct estimates indicated unemployment and the number of DSM-IV disorders directly impacted physical health status (similar to Model 4 reported in Table 2). The total (indirect and direct) estimates of the path analysis closely paralleled those reported in Model 4. Holding constant demographic variables, socioeconomic variables, and number of DSM-IV disorders, the results illustrate boarding school attendance was associated with lower physical health status scores indirectly and totally (direct and indirect combined).

Table 3.

Path Analysis of Physical Health Status Mediated by Number of Physical Health Conditions

| Indirect Relationship of Physical Health Status Mediated by Number of Health Problems(+) | Direct Relationship to Physical Health Status | Total (Indirect and Direct) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | 95% CI | Est | SE | 95% CI | Est | SE | 95% CI | |

| Attended Boarding School | −.83*** | 0.26 | −1.33, −.33 | −.39 | .41 | −1.20, .42 | −1.22** | .49 | −2.18, −.26 |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Aged 21+ | −1.94*** | 0.26 | −2.44, −1.44 | .09 | .50 | −.90, 1.07 | −1.83*** | .54 | −2.90, −.81 |

| Female | −1.08*** | 0.24 | −1.54, −.61 | −.40 | .41 | −1.20, .40 | −1.47** | .47 | −2.40, −.55 |

| Socioeconomic Variables | |||||||||

| Married/cohabitating | −.46 | 0.25 | −.94, .03 | −.32 | .42 | −1.14, .50 | −.78 | .49 | −1.73, .17 |

| High School Graduate or GED | .40 | 0.24 | −.06, .87 | −.14 | .42 | −.95, .67 | .26 | .49 | −.69, 1.21 |

| Unemployed | −1.36*** | 0.31 | −1.95, −.76 | −2.29*** | .49 | −3.25, −1.33 | −3.65*** | .58 | −4.78, −2.51 |

| Living below federal poverty level | −.03 | 0.26 | −.54, .48 | −.01 | .44 | −.87, .84 | −.04 | .52 | −1.06, .98 |

| Health Variable (past year) | |||||||||

| Number of DSM-IV disorders | −1.00*** | 0.2 | −1.40, −.60 | −.61* | .30 | −1.21, −.02 | −1.61*** | 0.36 | −2.31, −.91 |

| R-Squared | .31 | ||||||||

Note: Est= estimate, SE= standard error, CI= confidence interval,

value≤.05,

pvalue≤.01,

pvalue≤.001

(+)Number of self-reported health problems diagnosed by a doctor within the last year

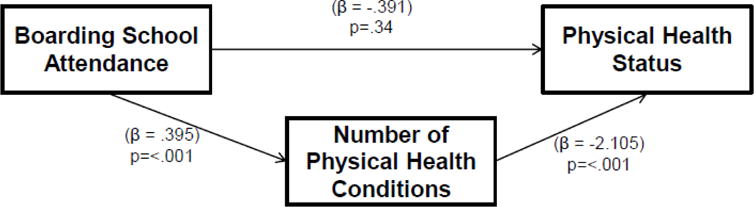

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the number of physical health conditions fully mediating the relationship of boarding school attendance and physical health status. Boarding school attendance is associated with an increase in the number of physical health problems which in turn is related to lower physical health status.

Figure 1.

shows the mediated relationship of boarding school attendance and physical health status (controlling for other variables in the model). The number of physical health problems fully mediated the relationship of boarding school attendance and physical health status producing an indirect result of (.395 *−2.105= −.83). Total results, combining the indirect and direct relationships (−.83+−.39= −1.22) of boarding school and physical health status are comparable to Model 4 prior to the introduction of the mediator.

Discussion

We hypothesized that boarding school attendance among NP tribal members would be associated with lower physical health status scores; our results confirm this hypothesis. As such, our findings complement work completed among Canadian Aboriginal People (First Nations Centre and Aboriginal Health Organization 2003; First Nations Centre 2005; Kaspar 2014). Similarly, to Kaspar’s (2014) work we demonstrated more than one pathway exists between boarding school attendance and poor physical health status. Kaspar’s (2014) work reported socioeconomic and community adversity mediated the relationship of boarding school attendance and physical health status, while we found the number of self-reported health problems mediated the relationship between boarding school attendance and physical health status.

Additionally, our analysis discovered that being female, 21 or older, unemployed, having more DSM-IV disorders, and more self-reported health problems were related to lower physical health status scores. We also found that women reported worse physical health status compared to men; in Kaspar’s (2014) work women had better health status than men. This difference may reflect different risk and protective factors at work that differentiate the Canadian and Northern Plains samples with regard to self-reported health. Kaspar (2014) reported that being married/cohabiting, higher education, and higher income increased the likelihood of reporting better health. We did not find statistically significant relationships among similar variables.

The impact of boarding school attendance on the health of AIs is complex. Future studies of the health consequence of AI boarding school attendance should explore unidentified mediational effects. Given the numerous attempts to force assimilation during AI boarding school attendance, additional unidentified, mediating paths may contribute to the explanation of the relationship between boarding school attendance and particular health outcome(s). Additionally, patterns of intergenerational impacts of boarding school attendance are worthy of exploration among US AI samples as there may be lasting effects that impact the current generation.

Recent research among a Canadian Aboriginal sample reported an intergenerational effect of boarding school attendance on psychological distress. Specifically, physiological distress increased as a function of the number of subsequent generations that attended boarding school (Bombay et al. 2014). Other research among non-Native populations revealed parental transmission of trauma to their children, whereby pre-conception trauma was passed to children through epigenetic alterations, referred to as epigenetic inheritance (Yehuda et al. 2015). That these intergenerational impacts persist underscores the potentially pervasive effect of boarding school attendance on AI health and well-being decades after this educational system and its attendant policies were abolished.

These analyses were subject to several limitations. Notably, we did not examine the relationship between physical health status and community adversity. Future investigations should explore the hypothesis that among AIs in the US, community adversity mediates the relationship between boarding school attendance and health outcome(s). Further, our analyses included only a sample of NP tribes; the generalizability of these results to other AI tribal communities is unknown. Though we focus on NP tribes, they are at high risk for many health-related problems. NP tribes have the highest AI death rates from alcohol, tuberculosis, and injury/poisoning; and the 2nd highest death rates from diabetes and heart disease (Indian Health Service et al. 2008). Moreover, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, liver disease, respiratory disease, stroke, and influenza/pneumonia are contributors to premature death for AIs compared to Caucasians residing in the NP area (Christensen and Kightlinger 2013). Though our dichotomy of the age variable serves as an important control variable marking key educational policy shifts, we may lose potential variation in the health status variable that may be associated with age. Additionally, though the data used in this analysis are over 15 years old, it is the best data available to study the relationship of boarding school attendance and health status among NP AIs. The impact of boarding school attendance on the physical health of NP AIs likely remains unchanged since the collection of this data. Although, dated the results are relevant and complement those emanating from similar work in Canada.

We used an AI specific theoretical model that suggests boarding school and genocide are central contributors to current AI health disparities (Warne 2015). The theoretical model also identifies racism and poor nutrition as adverse adult experiences that contribute to poor health. Our analyses focused only on the impact of boarding school attendance on physical health status. Though genocide, racism, and poor nutrition are theorized as a contributors to AI disease disparities our data did not contain appropriate measures with which to examine these other associations. Future studies including such constructs will build importantly on the current work and amplify the theoretical basis of the effects of childhood adversity into adulthood. Additionally, the physical health status variable is a general measure, as such it does not include disease specific information. For example, future analyses examining the association of AI boarding school attendance with specific chronic conditions will inform AI healthcare program planning and policy. Indeed, we argue that more work focused on the impact of boarding school attendance on the health of AIs is needed amongst tribes across the US.

Conclusion

Practitioners working with AI populations should seek to identify patients who have survived adverse boarding school experiences, determine the relevance of “boarding school syndrome” to their current health challenges, and connect them with services to assist with healing. The impact of boarding school attendance on the health and well-being of AIs needs to be better understood, tied to risk factors, and then inform interventions for families and younger generations. Doing so likely will credit the long recognized negative impact of boarding school attendance on lives, health, and well-being of American Indians. Such advances promise to facilitate the healing that AI boarding school survivors, tribal governments, and tribal organizations seek, as they work to redress the effects of this devastating experience (Wharton and Shelton 2015; The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition 2013–2014).

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under Award Number U54MD008164 (Elliott). This project was also supported by NIMHD P60 MD000507 (SM Manson) and NIMH R01 MH48174 (SM Manson).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards and Author Disclosures

Research Involving Human Subjects

This was a secondary analysis and was determined non-human subjects by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review boards. We also obtained tribal research review approval through institutional review boards or tribal resolution.

Informed Consent

This was a secondary data analysis project. Informed consent was obtained for the original data collection.

Contributions

Dr. Running Bear performed the literature search, completed the statistical analysis, and drafted sections of the manuscript. Drs. Beal and Kaufman assisted in the design of the study, selection of appropriate statistical analyses, and drafting and edited the manuscript. Dr. Manson assisted in the design of the study, assisted in obtaining the necessary human subjects approvals, and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Running Bear, Beals, Kaufman, and Manson have no actual or potential conflicts that could inappropriately influence their contribution to this manuscript.

References

- Adams DW. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the boarding school experience, 1875–1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Peters L. The psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33(2):80–88. doi: 10.1007/s001270050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence from tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton SS, Thommasen HV, Tallio B, Zhang W, Michalos AC. Health and quality of life of Aboriginal residential school survivors, Bella Coola Valley, 2001. Social Indicators Research. 2005;73(2):295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P, the AI-SUPERPFP Team Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: Walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):259–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1025347130953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Welty TK, Mitchell CM, Rhoades DA, Yeh JL, Henderson JA, et al. Different factor loadings for SF36: the Strong Heart Study and the National Survey of Functional Health Status. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(2):208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2014;51(3):320–338. doi: 10.1177/1363461513503380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasfield C. Residential school syndrome. British Columbia Medical Journal. 2001;43(2):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Child BJ. Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M, Kightlinger L. Premature mortality patterns among American Indians in South Dakota, 2000–2010. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(5):465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill W. Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The genocidal impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. Third. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Duran E, Yellow Horse M. Native Americans and the Trauma of Hisotry. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: a multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. [Review] Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(3):316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T, Walters KL, Pearson CR, Campbell CD. Indian boarding school experience, substance use, and mental health among urban two-spirit American Indian/Alaska natives. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):421–427. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.701358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Centre. The First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) 2002/03: Results for Adults, Youth, and Children Living in First Nations Communities. Ottawa, Ontario: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Centre, & Aboriginal Health Organization. What First Nations People Think About Their Health and Health Care: National Aboriginal Health Organization’s Public Opinion Poll on Aboriginal Health and Health Care in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heckert W, Eisenhauer C. A Case Report of Historical Trauma Among American Indians on a Rural Northern Plains Reservation. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2014;10(2):106–109. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- . Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978.

- . Indian Education Act of 1972. (Vol. 241).

- Indian Health Service, Office of Public Health Support, & Division of Program Statistics. Indian Health Service Regional Differences in Indian Health. Washington: Government Printing Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- . Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975.

- Jiang L, Beals J, Whitesell NR, Roubideaux Y, Manson SM, Team, T. A.-S. Health-related quality of life and help seeking among American Indians with diabetes and hypertension. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(6):709–718. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar V. The lifetime effect of residential school attendance on indigenous health status. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(11):2184–2190. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, Abelson JM, McGonagle KA, Kendler KS, Knauper B, et al. Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7(1):33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y, Coons SJ. An examination of self-reported chronic conditions and health status in the 2001 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. Current Medical Research & Opinion. 2005;21(11):1801–1808. doi: 10.1185/030079905X65655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lluch-Canut T, Puig-Llobet M, Sanchez-Ortega A, Roldan-Merino J, Ferre-Grau C, Positive Mental Health Research, G Assessing positive mental health in people with chronic physical health problems: correlations with socio-demographic variables and physical health status. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:928. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, Beals J. The utility of the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6) in two American Indian communities. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(3):752–761. doi: 10.1037/a0023288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Boarding School Abuses, Human Rights, and Reparations. Social Justice. 2004;31(4):89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools. Amnesty International Magazine 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Indigenous Peoples and Boarding Schools: A comparative study. New York: United Nations; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. 2013–2014 http://www.boardingschoolhealing.org/.Accessed 8/20/2015.

- The Regents of the University of Colorado. National Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. American Indian Services Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project. 2015 http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/PublicHealth/research/centers/CAIANH/NCAIANMHR/ResearchProjects/Pages/AI-SUPERPFP.aspx. Accessed July 14, 2015 2015.

- Ware JE., Jr . SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Warne D. American Indian health disparities: psychosocial influences. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2015;9(10):567–579. [Google Scholar]

- Wharton DR, Shelton BL. Boarding School Healing. 2015 http://www.narf.org/cases/boarding-school-healing/. Accessed 8/20/2015.

- Yehuda R, Daskalakis N, Bierer LM, Bader HN, Klengel T, Holsboer F, et al. Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biological Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.005. Available online 8/12/2015(In press, accepted manuscript) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellow Horse Brave Heart M. Gender differences in the historical trauma response among the Lakota. [Comparative Study] Journal of Health & Social Policy. 1999;10(4):1–21. doi: 10.1300/J045v10n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellow Horse Brave Heart M, Chase J, Elkins J, Altschul DB. Historical trauma among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):282–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellow Horse Brave Heart M, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian Holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. [Historical Article Review] American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziibiwing Center of Anishinable Culture and Lifeways. American Indian Boarding Schools: an exploration of global ethinc & cultural cleansing. In: Bosworth DA, editor. A supplementary Curriculum Guide: Ziibiwing Center of Anishinable Culture and Lifeways. 2011. [Google Scholar]