ABSTRACT

Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) catalyzes the interconversion of nucleoside diphosphates and triphosphates using ATP as phosphate donor. This housekeeping enzyme is present in several subcellular compartments. The main isoform (NDPK1) is located in the cytosol and is highly expressed in meristems and provascular tissues. The manipulation of NDPK1 levels in transgenic potato roots demonstrates that this enzyme plays a key role in the transfer of energy between the cytosolic adenine and uridine nucleotide pools and in the distribution of carbon between starch and cellulose. Modulation of the expression of NDPK1 also alters the homeostasis of root respiration, glycolytic flux, reactive oxygen species production and growth. Herein, we propose a model summarizing the effects of the manipulation of NDPK1 levels on root metabolism. The model also accounts for G-quadruplex DNA binding, a moonlighting activity recently attributed to NDPK1, which possibly contributes to the metabolic phenotype of transgenic roots.

Keywords: Nucleoside diphosphate kinase, carbon metabolism, starch, cellulose, respiration, reactive oxygen species, root, moonlighting enzyme

Introduction

Nucleoside diphosphate kinases (NDPKs, EC 2.7.4.6) catalyze the reversible transfer of the terminal phosphate from a donor nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) to an acceptor nucleoside diphosphate (NDP). In vivo, this housekeeping reaction mainly proceeds in the NTP generating direction, with ATP as phosphate donor (NDP+ATP→NTP+ADP). This reaction is therefore important for the homeostasis of NTP pools. In animal cells, NDPKs are also recognized to play additional roles in an array of unrelated processes including transcriptional regulation of gene expression,1 tumor metastasis,2 signalling,3 development,4 mitophagy,5 and DNA repair.6 This functional versatility may be mediated by various moonlighting activities, including histidine protein kinase activity,7 nuclease activity,8,9 or their ability to interact with numerous protein partners,10,11 DNA,1,6 or lipid bilayer.12,13

In plants, the NDPK family is divided into four types (I-IV) based on phylogenetic analyses and patterns of subcellular localization.14 Type I isoforms are represented by one or two genes, depending on the species and are predominantly cytosolic. Studies in potato demonstrate that NDPK1, belonging to Type I, constitute the bulk of NDPK activity and likely represents the most highly expressed isoform.14–16 In various species, expression of NDPK1 is spatio-temporally regulated during growth and development.17–20 In potato roots, immunolocalization studies have demonstrated the enhanced expression of NDPK1 in meristems and provascular tissues.15 Using data mining of available Arabidopsis expression datasets (http://bar.utoronto.ca/),21 we have compiled the expression of the five annotated NDPK genes in two different zones of root development22,(Figure 1). These data show that NDPK1 has a unique expression pattern among all NDPK genes. Maximum levels of NDPK1 expression are found in procambium cells while expression of genes for other isoforms are either absent (NDPK2, NDPK4 and NDPK5) or extremely low (NDPK3) in this cell type. This expression profile supports the previous hypothesis that NDPK1 could fulfill a key role to sustain primary cell wall deposition during early root growth.15 In this scenario, NDPK1 housekeeping activity provides UTP required as co-substrate for the cytosolic synthesis of UDP-glucose (UDPG) by UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGPase). UDPG is the major precursor for the synthesis of cellulose and other cell wall carbohydrates. Recently, we have used a genetic approach to test the implication of NDPK1 in carbohydrate metabolism.16 This work provides evidence that the above hypothesis is valid and that the role of NDPK1 in plants may very well lie beyond a simple housekeeping function.16

Figure 1.

Spatiotemporal expression levels of Arabidopsis NDPK genes in root tissues. (A) Left: Cross-section diagram of an Arabidopsis root from a 5–6 day old seedling taken from two different zones of development: young (meristematic zone) and old (elongation and maturation zones) as defined by ref. 22. Right: Schematic cut-away portion of stele in cross-section. Different root tissues are defined and color-coded. (B) Heatmap showing absolute spatiotemporal expression levels of NDPK genes in root tissues defined in (A). Expression values were obtained from Arabidopsis eFP Browser21 based on microarray root spatiotemporal map.22.

NDPK1 levels modify starch and cellulose contents in transgenic roots

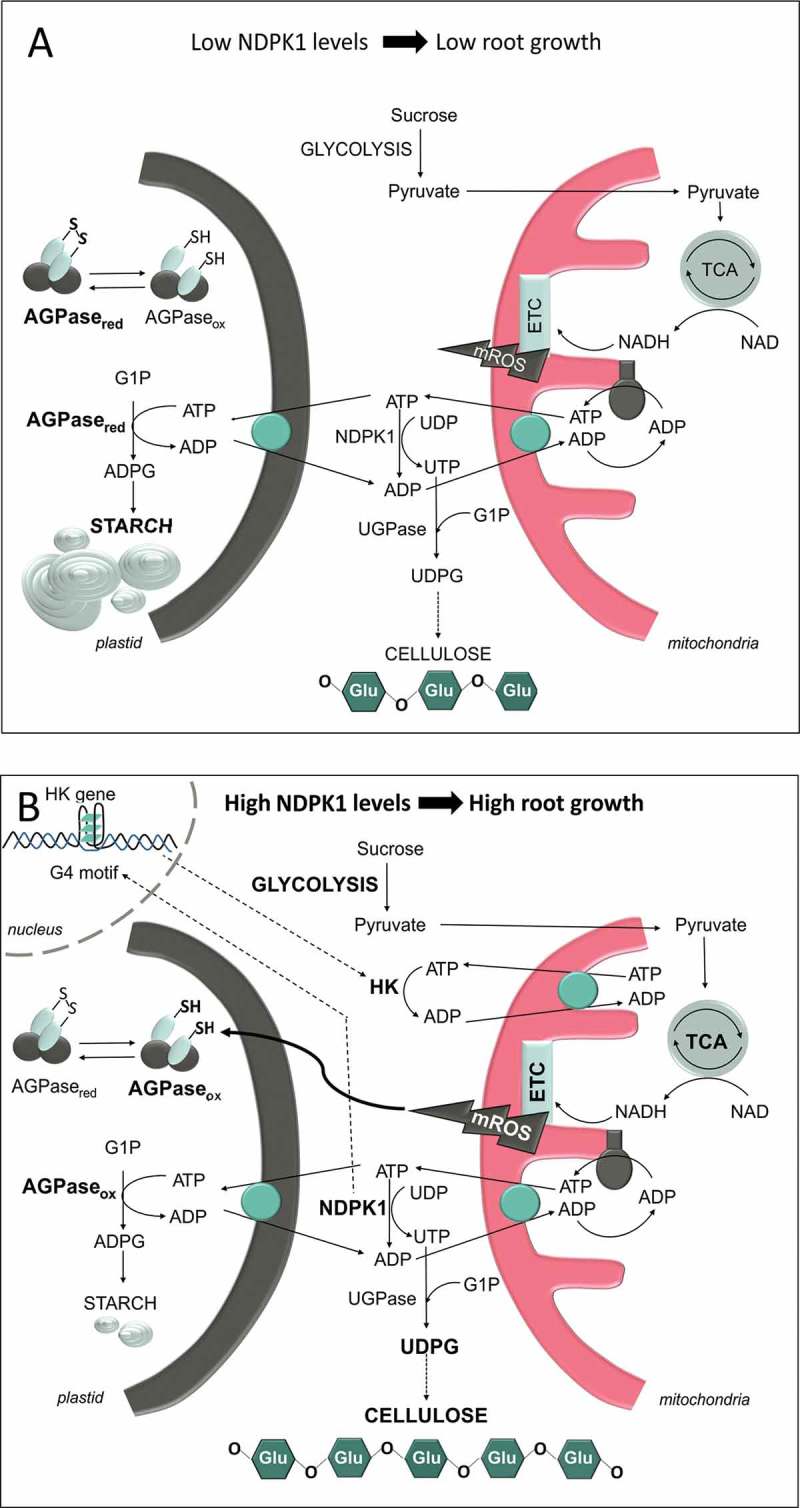

NDPK1 activity allows a straightforward transfer of energy between adenine and uridine nucleotide pools in the cytosol.23 The main effects of decreasing and increasing NDPK1 levels are respectively presented in Figure 2a and 2b. The antisense repression of NDPK1 decreases UTP synthesis and improves availability of ATP, which, in turn, favors metabolic pathways dependent on adenylates (e.g. starch synthesis) (Figure 2a). Conversely, increasing NDPK1 activity enhances the capacity for UTP generation and promotes the activity of metabolic pathways reliant on uridinylates (e.g. UDPG and cellulose synthesis) (Figure 2b). Data obtained with cotton fibers have led to a model in which the provision of UDPG for cellulose biosynthesis is due to metabolic channelling between sucrose synthase (SuSy) and the cellulose synthase complex at the plasma membrane.24 However, the extent of the implication of SuSy in this process has been a matter of controversy in recent years.25,26 Results obtained from the manipulation of NDPK1 expression suggests that the latter could also be relevant to cellulose biosynthesis.

Figure 2.

Schematic model showing the main effects of manipulating the expression of NDPK1 on carbohydrate and energy metabolisms in (A) antisense and (B) sense transgenic potato roots as detailed in the text. ADPG: ADP-glucose; AGPaseox and AGPasered: ADPG pyrophosphorylase oxidized and reduced forms, respectively; ETC: Mitochondria electron transport chain; G1P: Glucose-1-P; G4: G-quadruplex; HK: Hexokinase; mROS: Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; UDPG: UDP-glucose; UGPase: UDPG pyrophosphorylase; TCA: Tricarboxylic acid cycle. Bold characters depict increased values. Dotted lines represent links for which experimental data are incomplete or missing.

NDPK1 levels alters root growth, respiratory metabolism, cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and post-translational redox regulation of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase)

Interestingly, the manipulation of NDPK1 induced pronounced differences in growth, consistent with the growth-related expression of NDPK1 in meristematic and provascular tissues (Figure 1).15 The increase root growth associated with high NDPK1 activity level is sustained by higher rates of glycolytic flux and O2 uptake. This stimulation of respiration maybe linked to increased NDPK1 catalytic activity generating a high turnover rate of cytosolic ATP and consequently feeding ADP back to oxidative phosphorylation. It could also be connected to a possible channeling of ATP between cytosolic pyruvate kinase (PKc) and NDPK1, which were shown to interact in a recent survey.27 The interaction of PKc and NDPK1 would consequently serve to increase pyruvate production, thereby stimulating glycolytic and respiration rates. Increased respiration in NDPK1 root overexpressors, leads to higher mitochondrial ROS production. This results in an oxidation (inactivation) of AGPase, a key redox-regulated enzyme of starch synthesis, probably contributing to low starch levels in NDPK1 root overexpressors.

NDPK1 moonlighting as a regulator of gene expression?

An increase in hexokinase (HK) activity is observed in roots with high NDPK1 levels and could contribute to ATP turnover. Indeed, NDPK and HK produce ADP, which could be taken up by the mitochondrial adenylate translocator thereby stimulating respiration. The mechanism modulating HK expression in roots overexpressing NDPK1 could involve a moonlighting activity described for maize NDPK1 which was reported to bind a G-quadruplex (G4) DNA motif from the 5′UTR antisense strand of maize HK4 gene.28 Interestingly, this element is also present in other HK genes from several species (e.g. Arabidopsis, rice, and potato).16,29 Another NDPK1 moonlighting activity is suggested by a recent study providing evidence that Arabidopsis NDPK1 interacts with several proteins involved in translation initiation and mRNA processing or metabolism.27 This activity could also be implicated in the regulation of HK genes. However, the involvement of NDPK1 in the regulation of mRNA metabolism remains to be formally demonstrated. Moonlighting properties of NDPK1 could be even more widespread, as the enzyme also interacts with proteins involved in a variety of processes, including ROS detoxification, carbohydrate metabolism, signal transduction or cytoskeleton.27 Nevertheless, the functionality of these interactions has yet to be established.

Concluding remarks

Research on animal NDPKs has demonstrated that their moonlighting activities explain a large part of their functional complexity. Recent progress depicts an emerging picture in which this complexity could be similar for plant NDPK1. A transgenic approach supports the hypothesis that the housekeeping function of NDPK1 sustains respiration and supplies UTP necessary for synthesis of cell wall precursors during early root growth. Recent data suggest that moonlighting activities of plant NDPK1 could also contribute to the metabolic phenotype of transgenic roots.

Funding Statement

JR research is supported by grants from Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies [Projet de recherche en équipe 174601] and by a Discovery grant from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada [RGPIN 227271];

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Sharma S, Sengupta A, Chowdhury S.. NM23/NDPK proteins in transcription regulatory functions and chromatin modulation: emerging trends. Lab Invest. 2018;98(2):175–181. doi: 10.38/labinvest.2017.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan I, Steeg PS.. Metastasis suppressors: functional pathways. Lab Invest. 2018;98(2):198–210. doi: 10.38/labinvest.2017.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Taha IH, Heijman J, Feng Y, Vettel C, Dobrev D, Wieland T. Regulation of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling by NDPK/NME proteins and caveolins: an update. Lab Invest. 2018;98(2):190–197. doi: 10.38/labinvest.2017.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takács-Vellai K, Vellai T, Farkas Z, Mehta A. Nucleoside diphosphate kinases (NDPKs) in animal development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(8):1447–1462. doi: 10.07/s00018-014-1803-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlattner U, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Epand RM, Boissan M, Lacombe ML, Kagan VE. NME4/nucleoside diphosphate kinase D in cardiolipin signaling and mitophagy. Lab Invest. 2018;98(2):228–232. doi: 10.38/labinvest.2017.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puts GS, Leonard MK, Pamidimukkala NV, Snyder DE, Kaetzel DM. Nuclear functions of NME proteins. Lab Invest. 2018;98(2):211–218. doi: 10.38/labinvest.2017.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attwood PV, Muimo R, The actions of NME1/NDPK-A and NME2/NDPK-B as protein kinases. Lab Invest. 2018;98(3):283–290. doi: 10.38/labinvest.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaetzel DM, Zhang QB, Yang MM, McCorkle JR, Ma DQ, Craven RJ. Potential roles of 3ʹ-5ʹ exonuclease activity of NM23-H1 in DNA repair and malignant progression. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2006;38(3–4):163–167. doi: 10.07/s10863-006-9040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang QB, McCorkle JR, Novak M, Yang MM, Kaetzel DM. Metastasis suppressor function of NM23-H1 requires its 3 ‘-5 ‘ exonuclease activity. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(1):40–50. doi: 10.02/ijc.25307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marino N, Marshall JC, Steeg PS. Protein-protein interactions: a mechanism regulating the anti-metastatic properties of Nm23-H1. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;384(4–5):351–362. doi: 10.07/s00210-011-0646-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snider NT, Altshuler PJ, Omary MB. Modulation of cytoskeletal dynamics by mammalian nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) proteins. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2015;388(2):189–197. doi: 10.07/s00210-014-1046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tokarska-Schlattner M, Boissan M, Munier A, Borot C, Mailleau C, Speer O, Schlattner U, Lacombe ML. The nucleoside diphosphate kinase D (NM23-H4) binds the inner mitochondrial membrane with high affinity to cardiolipin and couples nucleotide transfer with respiration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(38):26198–26207. doi: 10.74/jbc.M803132200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francois-Moutal L, Ouberai MM, Maniti O, Welland ME, Strzelecka-Kiliszek A, Wos M, Pikula S, Bandorowicz-Pikula J, Marcillat O, Granjon T. Two-Step Membrane Binding of NDPK-B Induces Membrane Fluidity Decrease and Changes in Lipid Lateral Organization and Protein Cluster Formation. Langmuir. 2016;32(48):12923–12933. doi: 10.21/acs.langmuir.6b03789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorion S, Rivoal J. Clues to the functions of plant NDPK isoforms. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2015;388(2):119–132. doi: 10.1007/s00210-014-1009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorion S, Matton DP, Rivoal J. Characterization of a cytosolic nucleoside diphosphate kinase associated with cell division and growth in potato. Planta. 2006;224:108–124. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorion S, Clendenning A, Rivoal J. Engineering the expression level of cytosolic nucleoside diphosphate kinase in transgenic Solanum tuberosum roots alters growth, respiration and carbon metabolism. The Plant J. 2017;89:914–926. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SK, Chang MC, Tsai YG, Lur HS. Proteomic analysis of the expression of proteins related to rice quality during caryopsis development and the effect of high temperature on expression. Proteomics. 2005;5(8):2140–2156. doi: 10.02/pmic.200401105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Esteso MJ, Selles-Marchart S, Lijavetzky D, Pedreno MA, Bru-Martinez R. A DIGE-based quantitative proteomic analysis of grape berry flesh development and ripening reveals key events in sugar and organic acid metabolism. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(8):2521–2569. doi: 10.93/jxb/erq434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricardo CPP, Martins I, Francisco R, Sergeant K, Pinheiro C, Campos A, Renaut J, Fevereiro P. Proteins associated with cork formation in Quercus suber L. Stem Tissues. J Proteom. 2011;74(8):1266–1278. doi: 10.16/j.jprot.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo GF, Lv DW, Yan X, Subburaj S, Ge P, Li X, Hu Y, Yan Y. Proteome characterization of developing grains in bread wheat cultivars (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12147. doi: 10.86/1471-2229-12-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart NJ. An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” Browser for Exploring and Analyzing Large-Scale Biological Data Sets. Plos One. 2007;2(8):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brady SM, Orlando DA, Lee J-Y, Wang JY, Koch J, Dinneny JR, Mace D, Ohler U, Benfey PN. A High-Resolution Root Spatiotemporal Map Reveals Dominant Expression Patterns. Science. 2007;318(5851):801–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1146265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dancer J, Neuhaus HE, Stitt M. Subcellular compartmentation of uridine nucleotides and nuceloside-5ʹ-diphosphate kinase in leaves. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:637–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amor Y, Haigler CH, Johnson S, Wainscott M, Delmer DP. A membrane-associated form of sucrose synthase and its potential role in synthesis of cellulose and callose in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(20):9353–9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barratt DHP, Derbyshire P, Findlay K, Pike M, Wellner N, Lunn J, Feil R, Simpson C, Maule AJ, Smith AM. Normal growth of Arabidopsis requires cytosolic invertase but not sucrose synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(31):13124–13129. doi: 10.73/pnas.0900689106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Li J, Bahaji A, Almagro G, Montero M, Etxeberria E, Hidalgo M, Sesma MT, Pozueta-Romero J. Sucrose synthase activity in the sus1/sus2/sus3/sus4 Arabidopsis mutant is sufficient to support normal cellulose and starch production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(1):321–326. doi: 10.73/pnas.1117099109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luzarowski M, Kosmacz M, Sokolowska E, Jasinska W, Willmitzer L, Veyel D, Skirycz A. Affinity purification with metabolomic and proteomic analysis unravels diverse roles of nucleoside diphosphate kinases. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(13):3487–3499. doi: 10.93/jxb/erx183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopyov M, Bass HW, Stroupe ME. The maize (Zea mays L.) nucleoside diphosphate kinase1 (ZmNDPK1) gene encodes a human NM23-H2 homologue that binds and stabilizes G-quadruplex DNA. Biochemistry. 2015;54(9):1743–1757. doi: 10.21/bi501284g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg R, Aggarwal J, Thakkar B. Genome-wide discovery of G-quadruplex forming sequences and their functional relevance in plants Scientific Reports. 2016;6:28211. doi: 10.1038/srep28211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]