Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

More than half of older adults (age ≥ 65 yr) have 2 or more high-burden multimorbidity conditions (i.e., highly prevalent chronic diseases, which are associated with increased health care utilization; these include diabetes [DM], dementia, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], cardiovascular disease [CVD], arthritis, and heart failure [HF]), yet most existing interventions for managing chronic disease focus on a single disease or do not respond to the specialized needs of older adults. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify effective multimorbidity interventions compared with a control or usual care strategy for older adults.

METHODS:

We searched bibliometric databases for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating interventions for managing multiple chronic diseases in any language from 1990 to December 2017. The primary outcome was any outcome specific to managing multiple chronic diseases as reported by studies. Reviewer pairs independently screened citations and full-text articles, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We assessed statistical and methodological heterogeneity and performed a meta-analysis of RCTs with similar interventions and components.

RESULTS:

We included 25 studies (including 15 RCTs and 6 cluster RCTs) (12 579 older adults; mean age 67.3 yr). In patients with [depression + COPD] or [CVD + DM], care-coordination strategies significantly improved depressive symptoms (standardized mean difference −0.41; 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.59 to −0.22; I2 = 0%) and reduced glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (mean difference −0.51; 95% CI −0.90 to −0.11; I2 = 0%), but not mortality (relative risk [RR] 0.79; 95% CI 0.53 to 1.17; I2 = 0%). Among secondary outcomes, care-coordination strategies reduced functional impairment in patients with [arthritis + depression] (between-group difference −0.82; 95% CI −1.17 to −0.47) or [DM + depression] (between-group difference 3.21; 95% CI 1.78 to 4.63); improved cognitive functioning in patients with [DM + depression] (between-group difference 2.44; 95% CI 0.79 to 4.09) or [HF + COPD] (p = 0.006); and increased use of mental health services in those with [DM + (CVD or depression)] (RR 2.57; 95% CI 1.90 to 3.49; I2 = 0%).

INTERPRETATION:

Subgroup analyses showed that older adults with diabetes and either depression or cardiovascular disease, or with coexistence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure, can benefit from care-coordination strategies with or without education to lower HbA1c, reduce depressive symptoms, improve health-related functional status, and increase the use of mental health services.

Protocol registration:

PROSPERO-CRD42014014489

By the year 2050, 2 billion people worldwide will be aged 60 years and older.1,2 In Canada, older adults (age ≥ 65 yr) represent the fastest-growing proportion of the population — by 2036, they will make up 25% of the population and consume 62% of the health care budget.2 These projections, coupled with a rise in global life expectancies,1 will lead to an increased number of people who will develop high-burden chronic diseases (i.e., highly prevalent and associated with premature death and increased health care utilization).3 The burden of chronic disease is a global phenomenon, with more than half of older adults living with multimorbidity4 (co-existence of 2 or more chronic diseases).5 These trends are similar in Canada (42.6%),6,7 the United States (62.5%)8 and the United Kingdom (46.5% to 64.1%).9 Moreover, older adults with multimorbidity have greater health care needs, are at higher risk for adverse health outcomes and are admitted to hospital more frequently,10 yet only 55% receive appropriate care.7,8 In response, different interventions for managing chronic disease have been created (i.e., those that facilitate ongoing, proactive and preventive support for optimal management of disease). These strategies have potential to improve care for older adults,11,12 but are not usually developed for older adults nor sustainable, and focus only on a single disease.8,13,14

We know very little about the potential impact of interventions for managing multiple chronic diseases, and no existing systematic review focuses exclusively on older adults. To address these gaps, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify effective multimorbidity interventions (those that integrate the care of 2 or more high-burden chronic diseases) compared with a control or usual care strategy in older adults (age ≥ 65 yr), and to determine which components of these interventions optimize their impact.

Methods

Our systematic review protocol has been published15 and is registered with PROSPERO (the international prospective register of systematic reviews): registration no. CRD42014014489. We applied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)16 quality and publication standards.

Data sources and searches

An experienced information specialist executed our search strategy (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.171391/-/DC1) and a second information specialist appraised it using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist.17 We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, AgeLine and the Cochrane Library for studies in any language from 1990 to December 2017. This date restriction was applied because few multimorbidity studies were published before 1990.18 We applied a validated, age-specific search filter to focus our studies on older adults (age ≥ 65 yr).19 We searched the grey literature using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Grey Matters tool20 and scanned the reference lists of included studies to identify additional articles.

Study selection

Reviewer pairs were calibrated to ensure screening reliability. This exercise was repeated until there was at least 80% agreement, after which reviewer pairs selected the remainder of potentially relevant articles independently. The same procedure was used for selecting full-text articles. Disagreements at both levels were resolved through discussion.

Our eligibility criteria were informed by the PICO (patient, problem or population; intervention; comparison, control or comparator; and outcome) criteria.21 We included adults aged 65 years or older with multimorbidity (2 or more high-burden chronic conditions) as suggested by national and international public health agencies.22,23 We also considered adults older and younger than 60 years as long as the mean age of the study population was ≥ 65 years. Interventions for managing chronic conditions had to be deliberately created to address multimorbidity,5 whereby all study participants had to have the same chronic disease dyad or triad combination (e.g., diabetes [DM] + depression). We distinguished these from comorbidity cases that involved interventions that targeted people with the same index disease (e.g., DM) but could have different combinations of other diseases (i.e., some had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] as a comorbidity; others had heart failure [HF], osteoporosis, and so on),24 but overall the study population varied in terms of the combination of chronic diseases they had. Interventions for managing chronic disease could be complex (multiple components or targets), facilitate ongoing and proactive support for optimal disease management, and include quality improvement components.25,26 The comparator could be any control or usual care strategy.

The primary outcome could be any patient-relevant chronic disease management outcome as reported by studies (e.g., glycemic control as part of DM care). Secondary outcomes included quality of life, functional status (cognitive, physical, social, psychological functioning), treatment adherence, harms, satisfaction, health services utilization (e.g., hospital admission, emergency department visits) and costs. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental trials, and mixed-methods studies that included an RCT.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were abstracted in duplicate using a standardized, pilot-tested form on study characteristics, PICO follow-up and risk of bias. Outcomes were classified using the Cochrane Consumers and Communication group taxonomy27,28 (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.171391/-/DC1). Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool,29 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool,30 and GRADEPro (overall quality of evidence across our meta-analyses).31 Conflicts regarding all assessments were resolved through team discussion.

Deconstruction of interventions

To determine which component or combination of components contributed to outcomes, each strategy for managing chronic disease was deconstructed by reviewer pairs using content analysis.32 This involved extracting the description of the intervention for managing chronic disease from each article, identifying individual components and assigning a code to each (e.g., education, case management), drawing on the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of quality improvement strategies.25,26 This process led to the iterative development of a codebook of intervention components (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.171391/-/DC1).

Data synthesis and analysis

We summarized descriptively studies according to study and patient characteristics and assessed the effects of interventions for managing chronic disease across different outcomes. We explored the potential sources of statistical, methodological and clinical heterogeneity, and considered performing a meta-analysis for studies with the same outcome and similar combination of intervention com ponents (e.g., education plus case management). We defined high-statistical heterogeneity as I2 ≥ 75%.29 We used a random-effects model, given the expected high heterogeneity among complex interventions. For continuous outcomes, mean differences or standardized mean differences were used as effect measures, and relative risk (RR) with their confidence intervals (CIs) were used for binary outcomes. Planned subgroup analyses were used to investigate outcomes by disease cluster, type of intervention, and similar disease component combinations. All analyses were conducted using the R statistical package.

Ethics approval

Because this was a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies, no ethics approval was required.

Results

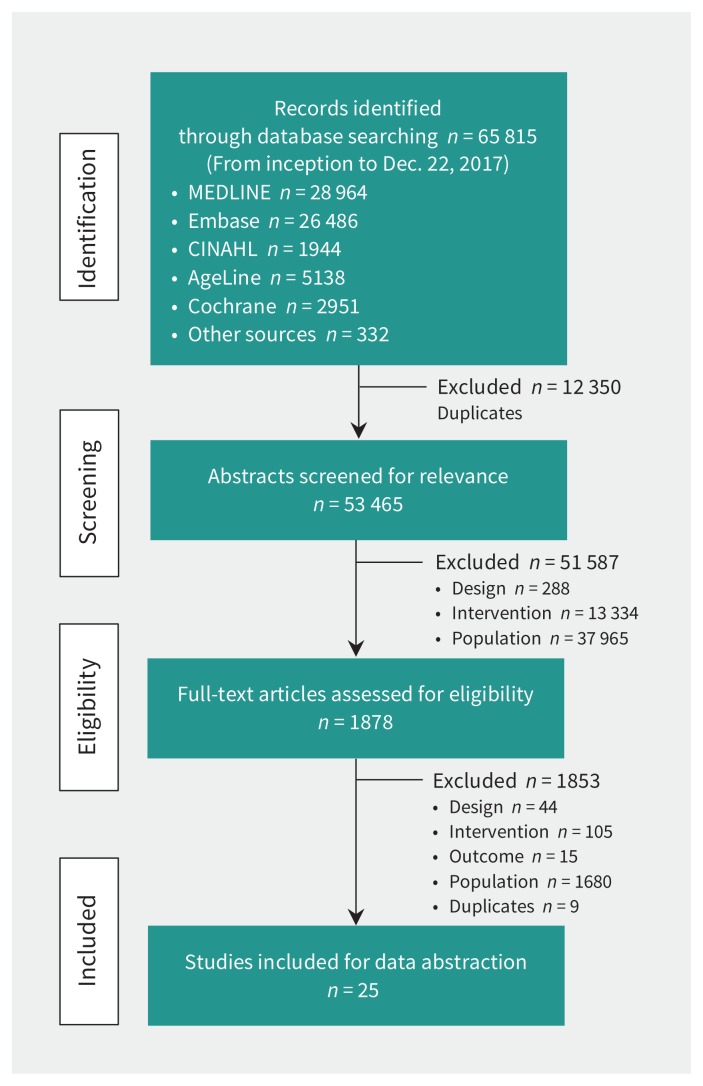

Figure 1 shows the flow of article selection. We screened 53 465 abstracts and identified 1878 potentially relevant full-text articles. Of these, 25 studies and 3 companion reports were included in the systematic review (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.171391/-/DC1), representing 12 579 older adults (mean age 67.3 yr, range 61–86 yr; 55% women).33–61 Designs were RCTs (n = 15), cluster RCTs (n = 6), mixed-methods (n = 3) and uncontrolled (n = 1) studies published between 2003 and 2018 in the US (n = 11), Australia (n = 7), Europe (n = 6) and Canada (n = 1). Follow-up ranged from 2 to 52 weeks (mean 26.3 wk). The most common chronic conditions occurring in disease clusters were DM (n = 13), depression (n = 10), HF (n = 7) and COPD (n = 7). The most frequently occurring disease dyads were [DM + depression (n = 4)44,49,60 or cardiovascular disease (CVD) (n = 4)40,49,53,56] and [HF + COPD (n = 3)46,52,57].

Figure 1:

Flow of article selection for the systematic review.

The types of interventions for managing chronic diseases are described in Appendix 3. Most studies were classified as care coordination (n = 10) or information and health technology (n = 7). Deconstruction of these interventions showed 9 components, of which the most frequently occurring were education targeting patients, providers or both (88%); disease management (52%); and self-management (48%). Interventions were delivered in primary care (n = 8), at home (n = 7), in outpatient clinics (n = 5), hospitals (n = 3), and nursing homes (n = 2).

The risk of bias assessment for the 21 included RCTs are shown in Appendix 5 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.171391/-/DC1). Most studies had low risk of bias for random-sequence generation (86%), blinding of outcome assessors (62%), incomplete or selective reporting of outcomes (88%) and other biases (86%); and unclear risk of bias for allocation sequence (48%) and blinding of patients or personnel (48%). Two studies (10%) had high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel.

All primary and secondary outcomes data are available in Appendices 6–12 (at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.171391/-/DC1).

Primary outcomes

Depression

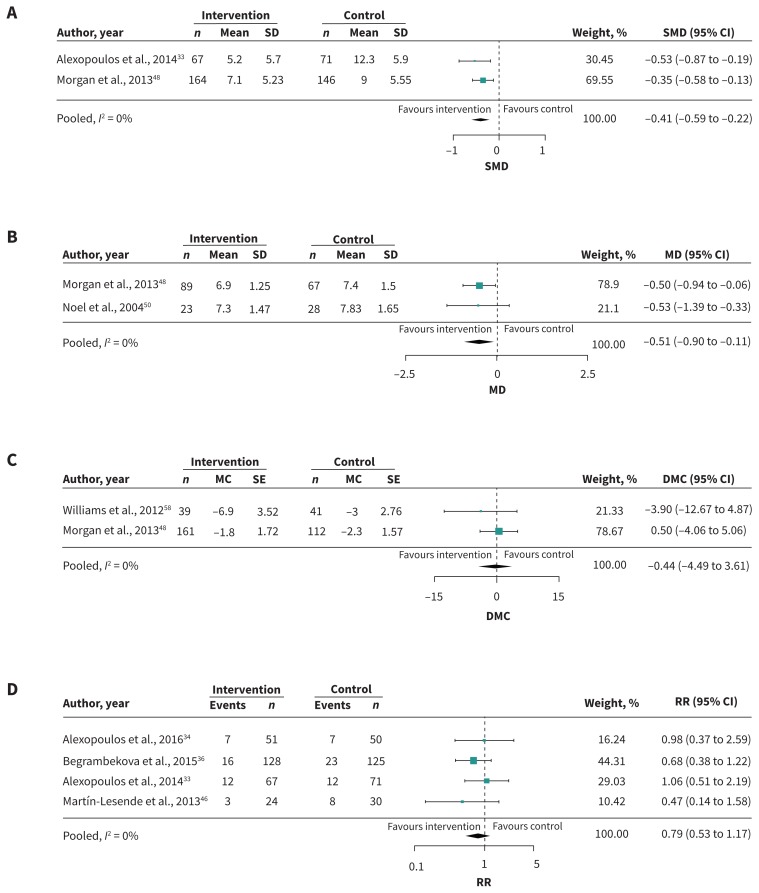

Of 14 studies investigating depression, 6 studies evaluating care-coordination interventions (n = 3314)33,45,47,48,55,60 and 2 studies of cognitive-behavioural interventions43,44 (n = 400) significantly reduced depressive symptoms in patients with [depression + another disease (COPD,33,44 arthritis,55 dementia43,47 or DM44,60)]; and for patients with [DM + CVD]48 (p value range < 0.001 to 0.021). The other studies did not report effect sizes. A subgroup of 2 trials (n = 448)33,48 of case management + self-management + education that were pooled in a meta-analysis showed significantly improved depressive symptoms in patients with [depression + COPD] or [CVD + DM] (standardized mean difference −0.41; 95% CI −0.59 to −0.22; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2A, Table 1).

Figure 2:

Meta-analysis of primary outcomes. (A) Depression: Care-coordination interventions with the exact intervention components of education (ED) + case management (CM) + self-management (SM) in patients with diabetes (DM) + depression (DEP), cardiovascular disease (CVD) or heart failure (HF) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) + DEP. (B) Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c): Care-coordination interventions with ED + CM as shared components in patients with DM + (CVD, COPD or DEP). (C) Systolic blood pressure: interventions with ED + SM as shared components in patients with DM + (chronic kidney disease or CVD). (D) Mortality: Care-coordination interventions with at least ED as the shared component in patients with COPD + (DEP or HF) or DEP + HF. Note: CI = confidence interval, DMC = difference in mean change, MC = mean change, MD = mean difference, RR = relative risk, SD = standard deviation, SE = standard error, SMD = standardized mean difference.

Table 1:

Summary of pooled results

| Outcome | Comparison | Intervention element(s) shared by RCTs | No. of RCTs (no. of patients) | Disease clusters (no. of RCTs) | Pooled effect size (95% CI) | I2*, % | GRADE† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes: chronic disease management | |||||||

| Depression | Care coordination; ED v. usual care or control | ED + CM + SM | 2 (448) | COPD + DEP (1) DM + CVD (1) |

SMD −0.41 (−0.59 to −0.22)‡ | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕○ Moderate |

| HbA1c | Care coordination; ED v. usual care | ED | 3 (500) | DM + CVD (1) DM + COPD + HF (1) DM + DEP (1) |

MD −0.27 (−0.66 to 0.13) | 50 | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

| ED + CM | 2 (207) | DM + CVD (1) DM + COPD + HF (1) |

MD −0.51 (−0.90 to −0.11)‡ | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕○ Moderate |

||

| Systolic blood pressure | ED; SM v. usual care | ED + SM | 2 (354) | DM + CKD (1) DM + CVD (1) |

DMC −0.44 (−4.49 to 3.61) | 0 | ⊕○○○ Very low |

| Mortality | Care coordination; ED; IHT v. usual care | ED | 4 (550) | COPD + DEP (2) COPD + HF (1) HF + DEP (1) |

RR 0.79 (0.53 to 1.17) | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕○ Moderate |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Use of mental health services | Care coordination; ED v. control | ED + CP | 2 (688) | DM + CVD DM + DEP |

RR 2.57 (1.90 to 3.49)‡ | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕○ Moderate |

Note: CI = confidence interval, CKD = chronic kidney disease, CM = case management, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CP = care pathways, CVD = cardiovascular disease, DEP = depression, DM = diabetes, DMC = difference in mean change, ED = education, HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin, HF = heart failure, IHT = information health technology, MD = mean difference, RCT = randomized controlled trial, RR = relative risk, SM = self-management, SMD = standardized mean difference.

Statistical heterogeneity as defined by the I2 statistic.29

GRADE was assessed using GRADEPro.31

Statistically significant.

Glycosylated hemoglobin

Three pooled studies (n = 2222)48,50,60 evaluating care coordination with education did not reduce glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in patients with [DM + another disease (mean difference −0.27; 95% CI −0.66 to 0.13; I2 = 50.12%)]. A subgroup of these (n = 421; 2 RCTs)48,50 consisting of case management + self-management in addition to education significantly reduced HbA1c levels (mean difference −0.51; 95% CI −0.90 to −0.11; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2B, Table 1).

Systolic blood pressure

Meta-analysis of 2 RCTs (n = 365)48,58 evaluating a strategy of education + self-management showed no difference between groups for reducing systolic blood pressure in patients with [DM + CVD or chronic kidney disease] (difference in mean change −0.44; 95% CI −4.49 to 3.61; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2C, Table 1).

Mortality

Meta-analysis of 4 RCTs of care-coordination interventions with education as at least 1 component (n = 550)33,36,38,46 showed decreased mortality across trials in patients with [COPD + (depression or HF)] or [HF + depression], but it did not reach significance (relative risk [RR] 0.79; 95% CI 0.53 to 1.17; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2D, Table 1).

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

Care-coordination strategies reduced functional impairment among patients with [arthritis + depression] (between-group difference −0.82; 95% CI −1.17 to −0.47)45 or [DM + depression] (between-group difference 3.21; 95% CI 1.78 to 4.63).60 In 3 studies (n = 1913) targeting patients with at least DM, care coordination significantly improved cognitive functioning (between-group difference 2.44; 95% CI 0.79 to 4.09),60 and a self-management strategy reduced DM-related emotional stress (effect size 1.06)49 in depressed patients. A telemedicine strategy improved cognition in patients with [HF + COPD] (p = 0.006).50 Telemedicine did not improve health status among 2 studies of patients with [DM + HF].39,40 Another study that added an integrated nursing and rehabilitation program at home to telemedicine (n = 112)52 significantly improved quality of life in patients with [HF + COPD] (p < 0.001), as did a care-coordination strategy involving case management administered by nurses (n = 1001)45 for [depression + arthritis] (p = 0.005); no effect estimates reported. Two care-coordination strategies significantly reduced dyspnea-related disability in patients with [depression + COPD] (p = 0.044)33 or [DM + depression] (p = 0.022),60 as did home-based telemonitoring in patients with [COPD + HF] (p = 0.0015);38 no effect estimates reported.

Antidepressant use

Two preplanned subgroup analyses of the Integrated Model for Patient Care and Clinical Trials (IMPACT) trial45,60 evaluating a care-coordination intervention with the components of care pathways, disease management and education found that patients with [depression + (arthritis or DM)] were significantly more likely to take antidepressants or partake in psychotherapy than in usual care (66% v. 52%, p < 0.001;45 82% v. 61%, p < 0.001,60 respectively).

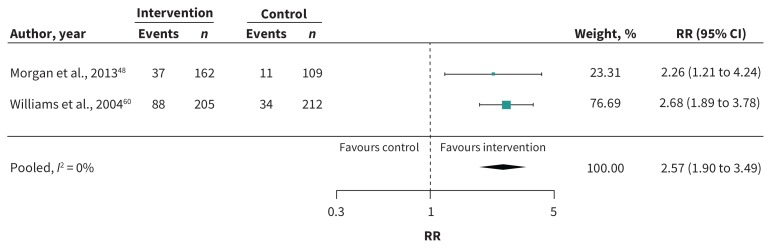

Mental health service use

Meta-analysis of 2 RCTs (n = 688)48,60 showed increased use of mental health services with care-coordination interventions that included at least education + care pathways, compared with controls among patients with [DM + (CVD or depression)] (RR 2.57; 95% CI 1.90 to 3.49; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3; Table 1).

Figure 3:

Meta-analysis of secondary outcomes. Use of mental health services: Interventions with education plus care pathways as shared components in patients with diabetes + (cardiovascular disease or depression). Note: CI = confidence interval, RR = relative risk.

Physical activity

Four studies investigated physical activity in patients with [DM + another disease].35,48,56,60 In particular, a collaborative-care strategy led by nurses (n = 317) significantly increased the number of patients who exercised 30 minutes per day compared with controls (60% v. 29%; p < 0.001)48 as did patients who received care coordination (between-group difference 0.50; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.89; p = 0.001).60

Health care utilization

In 3 studies investigating hospital admissions (n = 465),39,46,50 home telemonitoring (n = 58) targeting patients with [HF + COPD] reduced the risk for at least 1 all-cause hospital admission compared with controls (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.99; p = 0.033).46

Cost

In 2 studies investigating costs, neither found a difference between groups with telemedicine in patients with [COPD + DM + HF] (58% v. 47%; p > 0.05),50 and with care coordination in patients with [DM + depression];60 no effect estimates reported.

Interpretation

Overall, our findings showed that care-coordination interventions (i.e., changes in how, when and where health care is organized and delivered, and who delivers health care27) appear to have the greatest potential for improving primary and secondary outcomes in older adults with multimorbidity. More specifically, our subgroup analyses showed that first, the intervention combination of case management + education + self-management significantly reduced depressive symptoms in older adults with [depression + COPD] or [DM + CVD], and reduced HbA1c levels in those with [DM + another disease]. Second, care-coordination or telemedicine interventions that included at least education as a component significantly reduced dyspnea-related disability and improved cognitive functioning in patients with [DM + depression] or [COPD + HF]. Third, the intervention combination of care pathways and education significantly increased use of mental health services in those with [DM + (depression or CVD)].

These findings support those of previous studies that collaborative care is a promising approach for managing chronic disease,62 particularly for improving outcomes in patients who are depressed and have other co-existing chronic conditions.4,46,63 Of note, 92% of our meta-analyses included older adults with at least depression as part of the disease cluster, highlighting that depression is prevalent among co-existing conditions, in our study most often occurring in combination with DM. We therefore suggest that older adults with [depression + DM] can benefit from care-coordination strategies with or without education (targeting patients and providers) to lower HbA1c, reduce depressive symptoms and increase the use of mental health services.

We contributed to the current limited knowledge on which interventions are effective for older adults with multimorbidity. A Cochrane review investigated health service or patient-oriented interventions in patients of any age with multimorbidity and found mixed results,64 but suggested that strategies targeting specific risk factors or focusing on difficulties with daily functioning may be more effective.64 Our review builds on this work in several respects. We included a larger number of articles (n = 25) and older adults (n = 12 579) and identified interventions that were designed for specific combinations of chronic diseases (rather than for an index disease with co-existing conditions). We deconstructed interventions to help identify which studies were the most appropriate to pool in a meta-analysis and performed targeted searches for each chronic disease (embedded within our overall search strategy) to capture a broader perspective of multimorbidity. As such, we included a wider spectrum of disease clusters, intervention types, outcomes and settings, thereby making our systematic review among the most comprehensive of those investigating multimorbidity, and the only one targeting older adults specifically.

Our study highlights the paucity of interventions specifically created to address multimorbidity in older adults, particularly for chronic diseases that most frequently occur in clusters (DM, depression, HF, CVD and COPD). In particular, depression in DM is common, and because each can be a risk factor for the other, self-care and medication adherence are often substantial obstacles to improving outcomes.66 Future studies should investigate the potential impact of interventions that consider commonly occurring disease dyads: [DM + depression], [DM + CVD], [COPD + HF]. Stepped-care models of care (i.e., care that is adjusted in stages) have potential to effectively treat common disease dyads such as depression in DM,51,67,68 but require further evidence of effectiveness on patient-relevant outcomes for their routine use.

The lack of optimized strategies for managing multimorbidity (and common disease dyads) is also an indication that clinical practice guidelines that focus on the clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity are lacking. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline is one of the first to tackle this.69 In Canada, despite having good-quality guidelines, most focus on a single disease, and therefore have limited relevance and applicability to multimorbidity management.70 Second, multimorbidity management can be confusing for patients and overwhelming for providers because of the heterogeneous nature of multimorbidity71 disease and treatment interactions and possible conflicts,72,73 and the difficulty of attributing symptoms to conditions.71 Therefore, optimized multimorbidity management requires a better understanding of health priorities both from the patient and provider perspectives.

We conducted a realist review alongside our systematic review (to understand the underlying mechanisms of our findings), which confirmed this. When mitigating the complexities of multimorbidity management, patients tend to focus on reducing their undesired symptoms and preserving their quality of life, while providers focus on the conditions that most threaten a patient’s morbidity and mortality.74 As such, interventions need to consider not only the clinical aspects of care, but patients’ health priorities and goals, as well as their social and emotional vulnerabilities. Lastly, the mean follow-up period of our included studies was relatively short (mean 26.3 wk), which highlights an important gap in the literature — complex interventions are not designed for sustained use. This is consistent with our recent scoping review, which found that very few studies focus on the sustainability of implemented interventions.75 If interventions don’t have sustainability capacity, they are less likely to achieve desired outcomes and can even be harmful, and contribute to research waste.76 Future management interventions for multiple chronic diseases should be sustainable to optimize their impact, be designed and implemented to meet the specialized needs of older adults, and ensure a good balance between clinical and patient priorities.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. As with any systematic review, it is possible that we may not have captured all potentially relevant articles, particularly as we had a very large yield at both levels of screening. However, we conducted 5 (title or abstract) and 2 (full-text) calibration exercises with 6 reviewer pairs to attain our screening reliability goal. Additionally, an experienced information specialist developed our search strategy and another validated it using the PRESS checklist.17 This approach increases the overall quality of the evidentiary base of systematic reviews by enhancing the comprehensiveness of database searches and reducing the potential for errors.65 Second, 6 RCTs had missing data on certain outcomes that precluded meta-analyses; 2 authors provided missing data. Third, few studies defined multimorbidity, and fourth, studies ranged widely in the outcomes they considered and how they measured them. As such, there was potential for their misclassification. However, we used established Cochrane classification systems25,26,62 and pilot-tested all our systematic review tools at all stages of screening and abstraction, to optimize reliability. These processes also helped us to elucidate clinically relevant messages from high-quality trials. Lastly, we acknowledge that mid-aged adults also have a high prevalence of multimorbidity, but we focused on older adults because they represent a relatively unstudied population, and given their projected population growth, they urgently need our attention to optimize their care.

Conclusion

Care-coordination interventions with one or a combination of case management, care pathways, self-management and education appear to have the greatest potential for impact. In particular, older adults with [DM + (depression or CVD)] or [COPD + HF] can benefit from care-coordination or telemedicine strategies with or without education to lower HbA1c, reduce depressive symptoms, improve health-related functional status and increase the use of mental health services.

Acknowledgements

In addition to their core research team, the authors would like to thank the following research staff who helped throughout the screening and data abstraction phases of their systematic review: Chamila Adhihetty, Arnav Agarwal, Ronak Brahmbhatt, Ryan Kealey, Fissan Lau, Lori Wheelan and Lisa Ye. They also thank Laure Perrier, Becky Skidmore and Alissa Epworth for helping to develop and execute the search strategy.

See related article at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.181046

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/171391-res

Competing interests: Noah Ivers reports receiving personal fees and grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Government of Ontario during the conduct of the study; he also reports receiving personal fees from Diabetes Canada, outside the submitted work. Noah Ivers held a volunteer position as Chair of the Ontario Vascular Coalition, which envisioned a multicondition approach to management of chronic diseases and risk factors in primary care. Sharon Marr reports a patent issued for the trademark for the Geriatric Certificate program (February 2013). Geoff Wong reports that his salary is partly supported by The Evidence Synthesis Working Group of the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (Project Number 390). He is Deputy Chair of the UK National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment Out-of-Hospital Panel. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Monika Kastner conceived the study; Monika Kastner, Jemila Hamid, Geoff Wong, Noah Ivers and Sharon Straus developed the study design. Jemila Hamid conducted the meta-analyses. All of the authors drafted the manuscript, revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This research was supported by an Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC) Health Systems Research Fund (HSRF) Capacity Award. The MOHLTC had no role in the study’s design, conduct and reporting. Monika Kastner is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award. Noah Ivers is funded by a CIHR New Investigator Award and a Clinician Scientist Award from the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto. Jayna Holroyd-Leduc is funded by a University of Calgary BSF Chair in Geriatric Medicine. Sharon Straus is funded by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation.

Data sharing: The search strategy, extracted data and list of included studies are in the Appendices. Other data sets from this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Disclaimer: Monika Kastner and Jayna Holroyd-Leduc are associate editors for CMAJ and were not involved in the editorial decision-making process for this article.

References

- 1.Chatterji S, Byles J, Cutler D, et al. Health, functioning, and disability in older adults — present status and future implications. Lancet 2015;385:563–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada yearbook. Seniors. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2012. Cat no 11-402-X 2012. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-x/2012000/chap/seniors-aines/seniorsaines-eng.htm (accessed 2017 May 8). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Major non-communicable diseases and their risk factors. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available: www.who.int/ncds/en/ (accessed 2018 Aug. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Multimorbidity: technical series on safer primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252275/9789241511650-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 2018 Aug. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts KC, Rao DP, Bennett TL, et al. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease multimorbidity and associated determinants in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2015;35:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feely A, Lix LM, Reimer K. Estimating multimorbidity prevalence with the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37:215–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd C, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: How should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010;32: 451–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Badamgarav E, et al. Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illness — which ones work? Meta-analysis of published reports. BMJ 2002;325:925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:740–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasseville M, Chouinard MC, Fortin M. Patient-reported outcomes in multimorbidity intervention research: a scoping review. In J Nurs Stud 2018;77:145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastner M, Perrier L, Hamid J, et al. Effectiveness of knowledge translation tools addressing multiple high-burden chronic diseases affecting older adults: protocol for a systematic review alongside a realist review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, et al. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62: 944–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ 2012;345:e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kastner M, Wilczynski NL, Walker-Dilks C, et al. Age-specific search strategies for Medline. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grey matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2015. Available: www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters (accessed 2017 May 8). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone PW. Popping the (PICO) question in research and evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res 2002;15:197–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preventing chronic disease strategic plan 2013–2016. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Living long and well in the 21st century: strategic directions for research on aging. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefèvre T, Ivernois J-F, De Andrade V, et al. What do we mean by multimorbidity? An analysis of the literature on multimorbidity measures, associated factors, and impact on health services organization. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2014;62:305–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy; 2015. Ottawa: The Centre for Practice Changing Research; Available: http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy (accessed 2017 May 8). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shojania KG, Ranji SR, Shaw LK, et al. AHRQ technical reviews. In: Closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Vol. 2: Diabetes care Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cochrane Consumers & Communication: Outcomes of interest to the Cochrane Consumers & Communication Group. London (UK): Cochrane Group; 2012; Available: https://cccrg.cochrane.org/sites/cccrg.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/Outcomes.pdf (accessed 2018 Aug. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill S, Lowe D, McKenzie J. Identifying outcomes of importance to communication and participation. In: Hill S, editor. The knowledgeable patient: communication and participation in health. London (UK): Wiley Blackwell; 2011:40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62: 107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Sirey JA, et al. Untangling therapeutic ingredients of a personalized intervention for patients with depression and severe COPD. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:1316–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexopoulos GS, Sirey JA, Banerjee S, et al. Two behavioural interventions for patients with major depression and severe COPD. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;24:964–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker A, Herzberg D, Marsden N, et al. A new computer-based counselling system for the promotion of physical activity in patients with chronic diseases–results from a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begrambekova Y, Mareev V, Lomonosov M. Role of depression in effectiveness of disease management programs [abstract]. Eur Journal Heart Failure 2015;17(Suppl 1): 5–441. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begrambekova Y, Mareev V, Drobizhev M. Influence of psychoemotional disorders on the effectiveness of education and active outpatient control in heart failure patients. Russian J Cardiol 2016;136:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernocchi P, Vitacca M, La Rovere MT, et al. Home-based telerehabilitation in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2018;47:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowles KH, Holland DE, Horowitz DA. A comparison of in-person home care, home care with telephone contact and home care with telemonitoring for disease management. J Telemed Telecare 2009;15:344–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodaty H, Draper BM, Millar J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of different models of care for nursing home residents with dementia complicated by depression or psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doyle C, Bhar S, Fearn M, et al. The impact of telephone-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy and befriending on mood disorders in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Health Psychol 2017;22:542–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katon W, Unützer J, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care 2006;29:265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiosses DN, Rosenberg PB, McGovern A, et al. Depression and suicidal ideation during two psychosocial treatments in older adults with major depression and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;48:453–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamers F, Jonkers CC, Bosma H, et al. A minimal psychological intervention in chronically ill elderly patients with depression: a randomized trial. Psychother Psychosom 2010;79:217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:2428–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martín-Lesende I, Orruño E, Bilbao A, et al. Impact of telemonitoring home care patients with heart failure or chronic lung disease from primary care on healthcare resource use (the TELBIL study randomised controlled trial). BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McSweeney K, Jeffreys A, Griffith J, et al. Specialist mental health consultation for depression in Australian aged care residents with dementia: a cluster randomized trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:1163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morgan MA, Coates MJ, Dunbar JA, et al. The TrueBlue model of collaborative care using practice nurses as case managers for depression alongside diabetes or heart disease: a randomised trial. BMJ Open 2013;3. pii: e002171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naik AD, White CD, Robertson SM, et al. Behavioral health coaching for rural-living older adults with diabetes and depression: an open pilot of the HOPE Study. BMC Geriatr 2012;12:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noel HC, Vogel DC, Erdos JJ, et al. Home telehealth reduces healthcare costs. Telemed J E Health 2004;10:170–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pols AD, van Dijk SE, Bosmans JE, et al. Effectiveness of a stepped-care intervention to prevent major depression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or coronary heart disease and subthreshold depression: a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scalvini S, Bernocchi P, Baratti D, et al. Multidisciplinary telehealth program for patients affected by chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [abstract]. Proceedings from the European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure 2016 conference; 2016 May 21–24; Florence (Italy) Eur J Heart Failure 2016. (Suppl 1):94. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnipper JL, Linder JA, Palchuk MB, et al. Effects of documentation-based decision support on chronic disease management. Am J Manage Care 2010;16(12 Suppl HIT):SP72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sran M, Mercier J, Wilson P, et al. Physical therapy for urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or low bone density: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2016;23:286–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unützer J, Hantke M, Powers D, et al. Care management for depression and osteoarthritis pain in older primary care patients: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23:1166–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White KM, Terry DJ, Troup C, et al. An extended theory of planned behavior intervention for older adults with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Aging Phys Act 2012;20:281–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitten P, Mickus M. Home telecare for COPD/CHF patients: outcomes and perceptions. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams A, Manias E, Walker R, et al. A multifactorial intervention to improve blood pressure control in co-existing diabetes and kidney disease: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:2515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams A, Manias E, Liew D, et al. Working with CALD groups: testing the feasibility of an intervention to improve medication self-management in people with kidney disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Renal Soc Australas J 2012;8:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams JW, Katon W, Lin EH, et al. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:1015–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu CJ, Chang AM, Courtney M, et al. Peer supporters for cardiac patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Int Nurs Rev 2012;59:345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luijks H, Lucassen P, van Weel C, et al. How GPs value guidelines applied to patients with multimorbidity: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maly RC, Leake B, Frank JC, et al. Implementation of consultative geriatric recommendations: the role of patient-primary care physician concordance. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1372–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(3):CD006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 2004;27: 2154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hermanns N, Caputo S, Dzida G, et al. Screening, evaluation and management of depression in people with diabetes in primary care. Prim Care Diabetes 2013; 1:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Firth N, Markham M, Kellett S. The clinical effectiveness of stepped care systems for depression in working age adults: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2015;170: 119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farmer C, Fenu E, O’Flynn N, et al. Clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2016;354:i4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fortin M, Contant E, Savard C, et al. Canadian guidelines for clinical practice: an analysis of their quality and relevance to the care of adults with comorbidity. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sinnige J, Korevaar JC, Westert GP, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in a primary care population aged 55 years and over. Fam Pract 2015;32:505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luijks HD, Loeffen MJ, Lagro-Janssen AL, et al. GPs’ considerations in multimorbidity management: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e503–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harris MF, Dennis S, Pillay M. Multimorbidity: negotiating priorities and making progress. Aust Fam Physician 2013;42:850–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kastner M, Hayden L, Wong G, et al. Underlying mechanisms of complex interventions addressing the care of older adults with multimorbidity: a realist review. BMJ Open. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Cardoso R, et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2016;11:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moher D, Glasziou P, Chalmers I, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research: Who’s listening? Lancet 2016;387:1573–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]