Abstract

Fosfomycin is resurfacing as a “last resort drug” to treat infections caused by multidrug resistant pathogens. This drug has a remarkable benefit in that its activity increases under oxygen-limited conditions unlike other commonly used antimicrobials such as β-lactams, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides. Especially, utility of fosfomycin has being evaluated with particular interest to treat chronic biofilm infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa because it often encounters anaerobic situations. Here, we showed that P. aeruginosa PAO1, commonly used in many laboratories, becomes more susceptible to fosfomycin when grown anaerobically, and studied on how fosfomycin increases its activity under anaerobic conditions. Results of transport assay and gene expression study indicated that PAO1 cells grown anaerobically exhibit a higher expression of glpT encoding a glycerol-3-phosphate transporter which is responsible for fosfomycin uptake, then lead to increased intracellular accumulation of the drug. Elevated expression of glpT in anaerobic cultures depended on ANR, a transcriptional regulator that is activated under anaerobic conditions. Purified ANR protein bound to the DNA fragment from glpT region upstream, suggesting it is an activator of glpT gene expression. We found that increased susceptibility to fosfomycin was also observed in a clinical isolate which has a promoted biofilm phenotype and its glpT and anr genes are highly conserved with those of PAO1. We conclude that increased antibacterial activity of fosfomycin to P. aeruginosa under anaerobic conditions is attributed to elevated expression of GlpT following activation of ANR, then leads to increased uptake of the drug.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance (AMR), multi-drug resistance (MDR), fosfomycin, anaerobiosis, cystic fibrosis

Introduction

Although fosfomycin is classified as an old antimicrobial agent, it has recently re-attracted. This drug is still effective against multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens because there is no structural relationship between the drug and other commonly used antimicrobials such as β-lactams including carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides (Cassir et al., 2014). Fosfomycin is transported into the bacterial cells via GlpT and UhpT, glycerol-3-phosphate and glucose-6-phosphate symporters, respectively, then inhibits MurA activity, which transfers phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to the 3′-hydroxyl group of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine in the initial step for bacterial cell wall biosynthesis (Kadner and Winkler, 1973; Argast et al., 1978; Bush, 2012). This drug is rather more effective under anaerobic conditions whereas most of other drugs decrease their activities (Inouye et al., 1989; Bryant et al., 1992; Morrissey and Smith, 1994; Grif et al., 2001; Kohanski et al., 2010). In our previous studies on Escherichia coli, we found that FNR (Fumarate Nitrate Reduction) and CRP (cAMP receptor protein) are positive regulators of both glpT and uhpT genes, and activities of these regulators increase under anaerobic conditions, which results in increased intracellular accumulation of fosfomycin (Kurabayashi et al., 2015b, 2017).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a well-studied opportunistic pathogen. Its serious infections often occur in not only compromised hosts but also patients suffering from chronic respiratory infections such as cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (Murray et al., 2007; Turner et al., 2014). Treatment of P. aeruginosa infections is generally difficult because of its innate tolerance to antimicrobial agents (Hoiby, 2011; Poole, 2011). In addition, advanced multidrug resistant (MDR) strains have been often isolated in clinical settings (Obritsch et al., 2004; Aloush et al., 2006). Recently, utility of fosfomycin is proposed for treating MDR P. aeruginosa infections although P. aeruginosa produces an enzyme from the chromosomally encoded fosA gene that inactivates fosfomycin by transferring glutathione molecule to this drug (Rigsby et al., 2004, 2005). P. aeruginosa is a facultative anaerobe, and it is able to grow with nitrate or nitrite when oxygen is restricted (Schreiber et al., 2007). During infections, this bacterium often encounters oxygen-limited situations, for instance, when it forms a poly-microbial structure as biofilm, where bacterial cells in biofilm compete with other bacterial members to utilize oxygen (Worlitzsch et al., 2002; Yoon et al., 2002). As well as E. coli, P. aeruginosa is more susceptible to fosfomycin under anaerobic conditions compared to when it is grown under aerobic conditions (Inouye et al., 1989). However, unlike E. coli and its related members, P. aeruginosa lacks fnr and uhpT genes while glpT gene is conserved, hence fosfomycin uptake depends on only GlpT (Stover et al., 2000; Castaneda-Garcia et al., 2009).

We have been interested in obtaining insights into the mechanism how fosfomycin is more effective against anaerobically grown cells, which enables us to create an idea to enhance efficacy of fosfomycin treatment. In this study, we aim to study the mechanism how P. aeruginosa is sensitive to fosfomycin in situations grown under anaerobic conditions.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. A non-PAO1 P. aeruginosa clinical isolate designated Ps.a-682 was originally isolated from sputum in a hospitalized patient and is highly resistant to levofloxacin and aztreonam (MICs of 64 and 32 mg/L, respectively) and intermediate resistant to piperacillin and cefepime (MICs of 32 and 8 mg/L, respectively). Except in experiments to test drug susceptibility, all bacteria were grown in LB (Luria-Bertani) medium (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan). To grow P. aeruginosa, we supplied 0.5% (w/v) of potassium nitrate (KNO3) into the medium because this compound can be typically utilized as a substrate in the denitrification for facultative anaerobic growth (Schreiber et al., 2007). For drug susceptibility tests, bacteria were grown in Mueller Hinton medium (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) containing 0.5% of KNO3. P. aeruginosa strains were aerobically grown in glass tube with shaking at 160 rpm. For anaerobic cultures, we used a sealed container with gas generators, AnaeroPack-Anaero (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The cell growth was monitored by absorbance at 600 nm. For marker selection and maintaining plasmids, antibiotics were added to growth media at the following concentrations; 300 mg/L carbenicillin and 100 mg/L gentamicin for P. aeruginosa, 150 mg/L ampicillin, 15 mg/L chloramphenicol, and 20 mg/L gentamicin for E. coli.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype/phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| PAO1 | P. aeruginosa laboratory strain | Stover et al., 2000 |

| PAO1ΔglpT | glpT mutant from PAO1 | This work |

| Ps.a-682 | P. aeruginosa clinical isolate from sputum | This work |

| MG1655 | E. coli K12, wild-type, reporter strain | Blattner et al., 1997 |

| MC4100 | E. coli K12, lacking the endogenous lacZ gene | Casadaban, 1976 |

| RosettaTM(DE3) | T7-expression strain, CmR | Novagen/EMD Bioscience |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Gm | Suicide vector with a sacB gene; GmR | Hoang et al., 1998 |

| pBBR1MCS4 | Broad range host vector; ApR | Kovach et al., 1995 |

| pBBR1MCS4lacZ | pBBR1MCS4 with promoterless lacZ; ApR | This work |

| pBBRglpT(PAO1)-P | glpT promoter reporter from PAO1; ApR | This work |

| pBBRglpT(Ps.a-682)-P | glpT promoter reporter fromPs.a-682; ApR | This work |

| pBBRfosA(PAO1)-P | fosA promoter reporter from PAO1; ApR | This work |

| pBBRglpR(PAO1)-P | glpR promoter reporter from PAO1; ApR | This work |

| pNN387 | Single copy plasmid with promoterless lacZ; CmR | Elledge and Davis, 1989 |

| pNNglpT(PAO1)-P | glpT promoter reporter from PAO1; CmR | This work |

| pBBR1MCS5 | Broad range host vector; GmR | Kovach et al., 1995 |

| pBBR1MCS5glpT | GlpT expression; GmR | This work |

| pTrc99A | Vector for IPTG-inducible expression; ApR | Kurabayashi et al., 2015b |

| pTrc99Aanr | ANR expression in E. coli; ApR | This work |

| pQE80L | Vector for expression of His-tagged protein; ApR | Qiagen |

| pQE80anr | N-terminal His6-ANR overexpression plasmid; ApR | This work |

ApR, ampicillin resistance; CmR, chloramphenicol resistance; GmR, gentamicin resistance.

General Molecular Techniques

We used KOD-FX-Neo (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) as a DNA polymerase for PCR, and PCR was run on Bio-Rad T100 Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). The amplified DNA fragments were purified with PureLink PCR purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) when necessary. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA, United States). We used Ligation high Ver.2 as a reagent containing DNA ligase (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Plasmids were prepared from E. coli host using Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA Purification Systems (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, United States). These reagents and kits were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA sequencing was performed by the contract service supplied from Eurofins Genomics (Tokyo, Japan).

Cloning and Mutant Constructions

To construct in-frame deletion of glpT in PAO1 background, we performed a gene replacement strategy based on homologous recombination using pEX18Gm vector as previously described (Hoang et al., 1998). We amplified a flanking DNA fragment including both upstream and downstream region of glpT by sequence overlap extension PCR with primer pairs, delta1/delta2 and delta3/delta4 primers as listed in Table 2. The upstream flanking DNA included 450 bp and the first three amino acid codons. The downstream flanking DNA included the last two amino acid codons, the stop codon, and 450 bp of DNA. These deletion constructs were ligated into BamHI and HindIII-digested pEX18Gm and introduced into PAO1. We selected sucrose-resistant/gentamicin-sensitive colonies, and confirmed the resulting mutant strains using PCR analysis and DNA sequencing.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | DNA sequence (5′–3′) | Use |

|---|---|---|

| glpT-PA-delta1 | gcgggatccgtcggcgtgttctggggatc | glpT deletion construction |

| glpT-PA-delta2 | gagccgccgcgtcatcagccggctccgaacatcgcgagctccg | glpT deletion construction |

| glpT-PA-delta3 | aagcggagctcgcgatgttcggagccggctgatgacgcggcgg | glpT deletion construction |

| glpT-PA-delta4 | gcgaagcttatctggcggaactgcccgac | glpT deletion construction |

| lacZ-F | gcgggtacctttcacacaggaaacagctatg | pBBR1MCS4lacZ construction |

| lacZ-R | gcctctagattatttttgacaccagaccaac | pBBR1MCS4lacZ construction |

| glpT-PA-PF-NsiI | gcgatgcatcgccctcggccagcgcagg | pBBRglpT(PAO1)-P and pBBRglpT(Ps.a-682) construction |

| glpT-PA-PR-KpnI | gcgggtaccgcgagctccgcttgttgttg | pBBRglpT(PAO1)-P and pBBRglpT(Ps.a-682) construction |

| fosA-PF | gcgatgcatatggtcgaggtcgacgtgc | pBBRfosA(PAO1)-P construction |

| fosA-PR | gcgggtaccgggggctccttgcaagatg | pBBRfosA(PAO1)-P construction |

| glpR-PF | gcgatgcatagccggagtgcgacgagcc | pBBRglpR(PAO1)-P construction |

| glpR-PF | gcgggtaccgggttgttctcgtgctgcc | pBBRglpR(PAO1)-P construction |

| glpT-PA-PF-NotI | gcggcggccgccgccctcggccagcgcagg | pNNglpT(PAO1)-P construction |

| glpT-PA-PR-HindIII | gcgaagcttgcgagctccgcttgttgttg | pNNglpT(PAO1)-P construction |

| pBBRglpT-PA-F | gcgggtaccgcgggccggagcgatacac | pBBR1MCS5glpT construction |

| pBBRglpT-PA-R | gcgaagctttcagccggcttgctgcggc | pBBR1MCS5glpT construction |

| pTrcanr-F | gcgccatggccgaaaccatcaaggtgc | pTrc99Aanr construction |

| pTrcanr-R | gcgggatcctcagccttccagctggccgc | pTrc99Aanr construction |

| pQE80anr-F | gcgggatccgccgaaaccatcaaggtgcg | pQE80anr construction |

| pQE80anr-R | gcgaagctttcagccttccagctggccg | pQE80anr construction |

| glpT-PA-PR-6FAM | tcgcgagctccgcttgttg | DNase I footprinting analyses |

| glpT-PA-RACE1 | cagccgttgatgaagagcagg | 5′-RACE analysis |

| glpT-PA-RACE2 | ggccgaacggcaggaagacc | 5′-RACE analysis |

| glpT-PA-RACE3 | tggcgatggccgacatcgcg | 5′-RACE analysis |

We constructed lacZ reporter plasmids to measure promoter activities of glpT in PAO1 and Ps.a-682, and fosA and glpR in PAO1, designated pBBRglpT(PAO1)-P, pBBRglpT(Ps.a-682)-P, pBBRfosA(PAO1)-P, and pBBRglpR(PAO1)-P, respectively. The lacZ gene PCR-amplified from E. coli MG1655 (Blattner et al., 1997) was ligated into the broad-host-rage vector, pBBR1MCS4 (Kovach et al., 1995) digested with KpnI and XbaI to initially generate pBBR1MCS4lacZ. We, respectively, PCR-amplified the 300 bp region upstream of glpT from PAO1, and Ps.a-682 and fosA and glpR from PAO1 with primers listed in Table 2. These DNA fragments were, respectively, ligated into pBBR1MCS4lacZ digested with NsiI and KpnI, then the region sequence containing lac promoter between NsiI and KpnI sites on the parent vector was replaced with that of glpT, fosA or glpR promoter.

We also constructed pNNglpT(PAO1)-P, a lacZ reporter plasmid to measure glpT promoter activity of PAO1 in E. coli, the heterologous host background. We PCR-amplified the 300 bp region upstream of this gene with primers, glpT-PA-PF-NotI and glpT-PA-PR-HindIII, and ligated it into NotI and HindIII-digested pNN387 plasmid with promoterless lacZ (Elledge and Davis, 1989).

To construct glpT expression plasmid, pBBR1MCS5glpT, we PCR-amplified the glpT gene and its 201 bp region upstream, then ligated into pBBR1MCS5 (Kovach et al., 1995) digested with KpnI and HindIII.

To construct ANR and His6-ANR expression plasmids, pTrc99Aanr and pQE80anr, respectively, the anr gene was PCR-amplified with the primer pair shown in Table 2. These products were ligated into pTrc99A plasmid digested with NcoI and BamHI and pQE80L plasmid (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) digested with BamHI and HindIII. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Fosfomycin Susceptibility Assays

MIC assays were performed by a serial agar dilution method with the standard method of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2011). The MICs were determined as the lowest concentration at which growth was inhibited. We also performed disk assays using BD Sensi-Disc Fosfomycin 50 (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States). The susceptibility to fosfomycin of P. aeruginosa strains was evaluated by the diameter (mm) of inhibitory zones on the Mueller Hinton agar culture. For these assays, bacteria were aerobically or anaerobically grown for 20 h (for aerobic cultures) or 22 h (for anaerobic cultures) in the Mueller Hinton medium containing KNO3 because the anaerobic growth was moderately slower than aerobic growth even when KNO3 is present.

Fosfomycin Active Transport Assays

Assays to test fosfomycin accumulation in bacterial cells were conducted as previously described (Kurabayashi et al., 2014). Bacteria were grown in 20 ml of LB medium containing 0.5% of KNO3 to late-logarithmic phase and re-suspended in 1 ml of LB. This suspension was incubated for 60 min at 37°C in the presence of 2 mg of fosfomycin per ml, and then washed at three times with hypertonic buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.3], 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 150 mM NaCl) to remove the antibiotic. Cells were re-suspended in 0.5 ml of distilled water and plated on LB agar to determine the number of colony forming units (CFU)/ml. The bacteria re-suspension was boiled at 100°C for 3 min to release the fosfomycin. After centrifugation, the antibiotic concentration in the supernatant was determined by a diffusion disk assay. In this assay, sterilized assay disks (13 mm; Whatman, Florham Park, NJ, United States) were saturated with 0.1 ml of the supernatant and deposited onto LB agar plates overlaid with a 1:10 dilution of an overnight culture of E. coli MG1655 as a reporter strain (Blattner et al., 1997). Commercial fosfomycin was used to make a standard curve (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Fosfomycin concentration in supernatants was quantified by the diameter (mm) of inhibitory zones on the LB agar culture and represented as ng per 107 cells.

Overexpression and Purification of His6-ANR

N-Terminal six histidine tagged ANR protein, His6-ANR was expressed in and purified from E. coli RosettaTM (DE3) (Novagen/EMD Bioscience, Philadelphia, PA, United States). Bacteria containing recombinant plasmid were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.4 in LB, 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-b-D-thiogalactopyranoside) was then added, and culture growth was continued for 3 h. Cells were harvested and disrupted in EzBactYeastCrusher containing 60 mg/L lysozyme (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). The equal volume of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.9], 500 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol) was added to the cell lysate. After centrifugation, the resulting supernatant was mixed with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) for 1 h. After washed with 50 mM imidazol twice, His6-ANR was eluted with 200 mM imidazol. The purified protein was dialyzed (1-kDa cutoff) in buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0). The protein was >95% pure as estimated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). The purified protein was incubated with 100 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 0.1 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) for 4 h prior to footprinting experiment. ANR carries a [4Fe–4S] cluster in the active center as well as FNR that is produced by E. coli (Yoon et al., 2007). FNR loses its activity in the presence of oxygen because ferrous ions in [4Fe–4S] cluster are oxidized to ferric irons, then dimeric active form is dissociated (Green et al., 1996). That protein is able to form a dimer in the presence of high concentration of reducing agent like DTT even under aerobic conditions (Sharrocks et al., 1991). Therefore, we expected that activity of the purified ANR protein can be maintained in the presence of high concentration of DTT together with ferrous ions.

DNase I Footprinting

DNase I footprinting was performed using a previously described non-radiochemical capillary electrophoresis method on an ABI PRISM genetic analyzer equipped with an ABI PRISM GeneScan (Hirakawa et al., 2005). The 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled (5′), 301-bp DNA fragments (starting at 300 bp upstream of the glpT start codon and ending 1 bp upstream of the glpT start codon) was generated by PCR amplification with primer pairs a 6-FAM labeled reverse primer (glpT-PA-PR-6FAM) and an unlabeled forward primer (glpT-PA-PF-NsiI). The DNA fragment (0.45 pmol) was mixed with purified ANR protein (0–30 pmol) in a 50 μl reaction mixture. After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, DNase I (2.5 units, Promega Corp., Madison, WI, United States) was added. After incubation for 60 s at room temperature, samples were purified for electrophoresis on the ABI PRISM genetic analyzer apparatus.

Promoter Assays

P. aeruginosa strains carrying pBBRglpT(PAO1)-P, pBBRglpT(PA-682)-P, pBBRfosA(PAO1)-P or pBBRglpR (PAO1)-P, each LacZ reporter plasmid were aerobically or anaerobically grown overnight (∼16 h) at 37°C in LB medium containing 0.5% of KNO3. E. coli MC4100 (Casadaban, 1976) strains carrying pNNglpT(PAO1)-P, the LacZ reporter plasmid together with pTrc99A or pTrc99Aanr, the anr overexpression plasmid were anaerobically grown at 37°C in LB medium containing 0.1 mM of IPTG. Each cell culture of 0.5 ml was transferred into a 1.5-ml microtube, and 50 μl of chloroform was added to lyse the cells. After incubation for 5 min, the chemiluminescent signal in the supernatant was generated using a Tropix Galacto-Light Plus kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). The β-galactosidase activity was determined as the signal value normalized to an OD600 of 1.

5′-RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA End) Analysis

5′-RACE was performed according to a method as described previously (Kurabayashi et al., 2015a). We isolated total RNA from the logarithmic phase PAO1 and synthesized cDNA with the unique primer glpT-PA-RACE1 (starting at 396 bp inside the glpT-coding region). To obtain a single RACE product, two-step PCR were performed by using an oligo(dT) primer attached to a 22-base anchor sequence at the 5′ end [primer oligo(dT)-Anchor] and primer glpT-PA-RACE2 (starting at 300 bp inside the glpT-coding region) for the first round, and an anchor primer without the oligo(dT) sequence (PCR anchor) and primer glpT-PA-RACE3 (starting at 217 bp inside the glpT-coding region) for the second round. The obtained 260–290-bp product was TA-cloned, and eight clones were sequenced.

Statistical Analysis

P-value in each assay was determined by unpaired t-test and two-way ANOVA with the GraphPad Prism version6.00.

Results

P. aeruginosa PAO1 Strain Is More Susceptible to Fosfomycin When Anaerobically Grown

Initially, to confirm that the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to fosfomycin indeed increases under anaerobic conditions, we determined the MICs by an agar dilution method for P. aeruginosa when aerobically or anaerobically grown. In this study, we used the PAO1 strain because it has been commonly used for P. aeruginosa studies in laboratory. PAO1 exhibited a relatively low susceptibility to fosfomycin when aerobically grown possibly due to the production of inactivation enzyme from the fosA gene in chromosome (MIC: 64 mg/L) (Table 3). On the other hand, when anaerobically grown, the bacterial cells showed an eightfold lower MIC compared to the cells when aerobically grown (MICs: 8 mg/L for anaerobically grown cells vs. 64 mg/L for aerobically grown cells) (Table 3). To confirm the result of the agar dilution assays, we also performed disk assays. We found that the inhibitory zone of growth formed by fosfomycin for cells when anaerobically grown was larger than that for cells when aerobically grown (diameters: 24 ± 2 mm for anaerobically grown cells vs. 15 ± 1 mm for aerobically grown cells). These results indicate that P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain is more susceptible to fosfomycin when anaerobically grown.

Table 3.

Fosfomycin MICs of P. aeruginosa and its derivatives.

| Strain | Fosfomycin MICs (mg/L) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Anaerobic | |

| PAO1 | 64 | 8 |

| PAO1ΔglpT | >1024 | >1024 |

| PAO1ΔglpT/pBBR1MCS5 | >1024 | >1024 |

| PAO1ΔglpT/pBBR1MCS5glpT | 8 | 4 |

| Ps.a-682 | 64 | 16 |

The glpT Gene Expression of P. aeruginosa Increases when Anaerobically Grown, Resulting in Increased Uptake of Fosfomycin

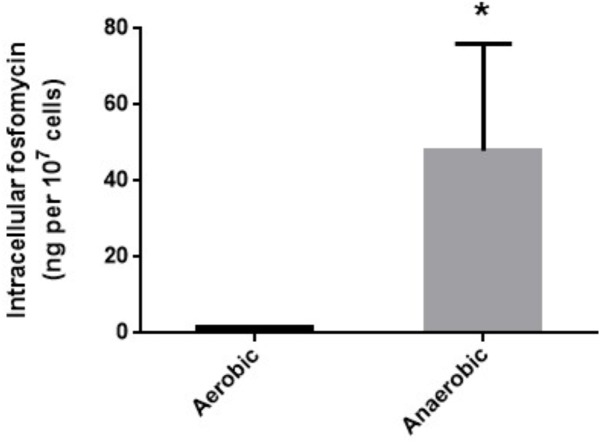

We measured intracellular levels of fosfomycin in anaerobically and aerobically grown cells by transport assay as described in “Materials and Methods” section. The fosfomycin level in cells anaerobically grown was 28-fold higher than that in cells aerobically grown (1.7 ± 0.1 ng/107 cells for aerobically grown cells vs. 47.9 ± 19.0 ng/107 cells for anaerobically grown cells) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Intracellular accumulation of fosfomycin in PAO1 grown under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Accumulation was described as amounts of fosfomycin (ng) in 107 cells. Data plotted are the means from three independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviations, ∗P< 0.05. Asterisks denote significance for values of intracellular fosfomycin amount in bacterial cultures under anaerobic conditions relative to those under aerobic conditions.

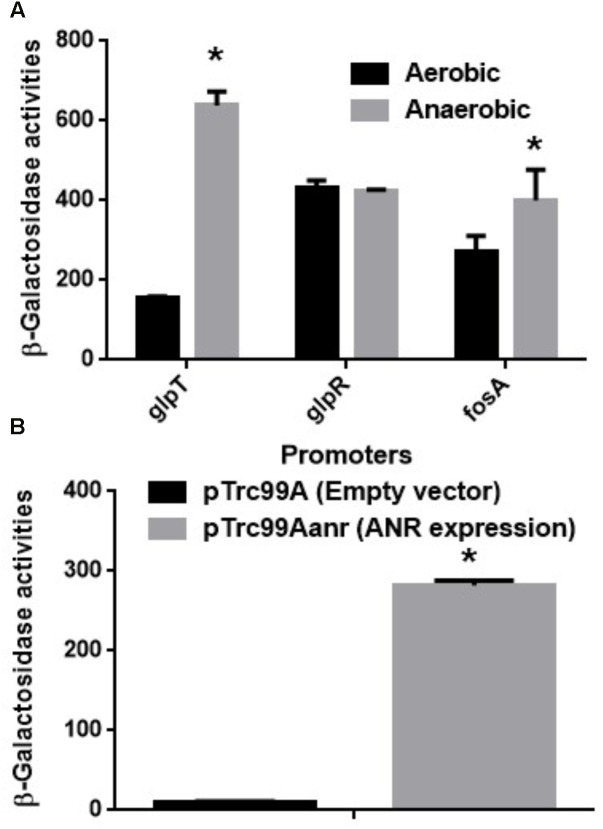

GlpT is an only transporter for fosfomycin uptake in P. aeruginosa since it lacks the uhpT gene (Castaneda-Garcia et al., 2009). Therefore, we also measured promoter activity of glpT in PAO1 cells carrying the lacZ reporter plasmid when grown aerobically and anaerobically. The LacZ activity from the glpT promoter in anaerobically grown cells was 4.5-fold higher than that in aerobically grown cells (Figure 2A). In addition, we constructed the glpT mutant (designated as PAO1ΔglpT), then examined the susceptibility to fosfomycin when it was grown under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. PAO1ΔglpT was very highly resistant to this drug even when grown under anaerobic conditions (MICs: >1,024 mg/L; diameters of inhibitory zone: 7 ± 1 mm for both aerobic and anaerobic cultures) (Table 3). When pBBR1MCS5glpT as an exogenous glpT expression plasmid was introduced into this strain, its susceptibility was increased above the parent level because glpT could be additively expressed due to the leak from the lac promoter on the plasmid in addition to its own promoter (MICs: 4 mg/L for anaerobically grown cells vs. 8 mg/L for aerobically grown cells; diameters of inhibitory zone: 29 ± 1 mm for anaerobically grown cells vs. 23 ± 1 mm for aerobically grown cells) (Table 3). These combined results indicate that increased susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to fosfomycin under anaerobic conditions is due to elevated expression of GlpT that leads to increased intracellular accumulation of the drug.

FIGURE 2.

(A) β-Galactosidase activities of PAO1 containing pBBRglpT(PAO1)-P, pBBRglpR(PAO1)-P or pBBRfosA(PAO1)-P, the lacZ reporter plasmid grown under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. (B) β-Galactosidase activities correspond to glpT promoter activities of PAO1 in E. coli MC4100, the heterologous host containing pNNglpT(PAO1)-P, the lacZ reporter plasmid with pTrc99A (empty vector) or pTrc99Aanr (anr expression plasmid). Data plotted are the means from three independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviations, ∗P< 0.01. Asterisks denote significance for values of glpT promoter activity in PAO1 cultured under anaerobic conditions relative to those under aerobic conditions or in MC4100 with anr gene expression relative to those without anr gene expression.

GlpR is a repressor for the glpT gene expression, then it might participate in the increase in glpT expression during anaerobic growth. To test this hypothesis, we examined glpR expression between aerobic and anaerobic conditions by measuring its promoter activities in PAO1 carrying the lacZ reporter plasmid, pBBRglpR(PAO1)-P. However, we observed no significant difference in glpR expression between both conditions (Figure 2A). Apart from GlpT, P. aeruginosa produces chromosomally encoded FosA that confers innate tolerance by inactivating fosfomycin (Rigsby et al., 2004; Rigsby et al., 2005). As unexpected, the activity of fosA promoter in cells when grown anaerobically was rather slightly higher than that in cells when grown aerobically although we do not know this precise reason (Figure 2A).

Anaerobic Regulator, ANR Contributes to Elevation of glpT Expression Under Anaerobic Conditions

ANR is a transcriptional regulator to activate subsets of genes that are essential for anaerobic growth in P. aeruginosa (Sawers, 1991). It is homologous with FNR of E. coli, and activated when oxygen is absent (Yoon et al., 2007). We hypothesized that ANR might contribute to elevation of glpT expression under anaerobic conditions. However, genes activated by ANR include nar operon which encodes nitrate reductase utilized for denitrification (Schreiber et al., 2007). Therefore deletion of anr notably decreases cell growth of P. aeruginosa when cultured under anaerobic conditions, then the growth defect might affect results of the promoter assay to evaluate glpT expression. To avoid this issue, we introduced pNNglpT(PAO1)-P, a lacZ reporter plasmid to measure glpT promoter activity of PAO1, together with pTrc99Aanr, an ANR expression plasmid or pTrc99A, the empty vector, into E. coli, the heterologous host lacking its chromosomal lacZ gene. We found that a LacZ expression from the reporter plasmid in E. coli carrying pTrc99Aanr was 28-fold higher than that in E. coli carrying the empty vector (Figure 2B).

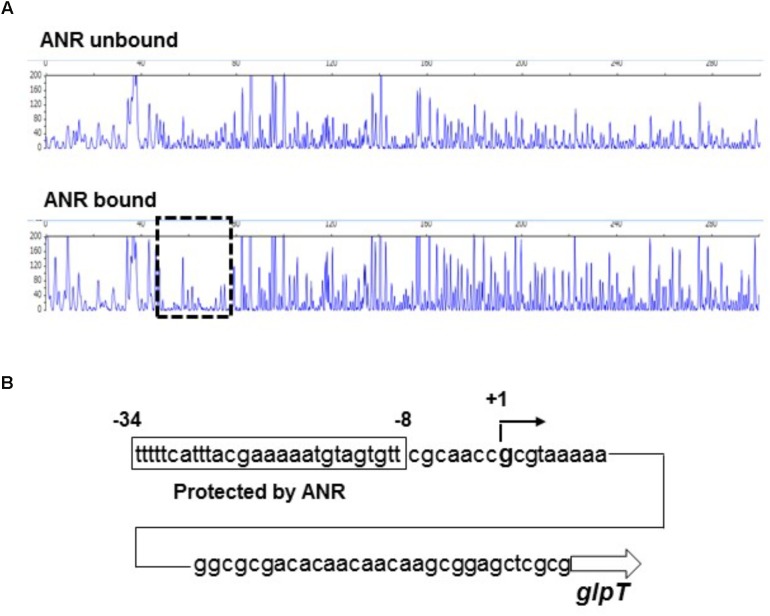

We tested whether ANR binds to the region upstream of glpT including the promoter or not by DNase I footprinting analyses. As described in section “Materials and Methods,” to evaluate the activity of ANR to bind target DNA in the presence of oxygen, we incubated the ANR protein with high amount of DTT prior to the binding assay to reactivate the protein. We found that a 27-bp region located at 47- to 73-bp upstream of glpT translational start is protected from DNase I digestion by ANR (Figure 3A). The protected region contained the sequence (TTCAT-ttac-GAAAA) that is similar to a proposed ANR-binding consensus motif (TTGAT-N4-ATCAA) (Winteler and Haas, 1996; Yoon et al., 2007), suggesting that ANR binds to this site (Figure 3B). The result of 5’-RACE analysis showed that the transcription of glpT is initiated from a G residue located at 39 bases upstream of translational start site, which corresponds to 18 bases downstream of the proposed ANR-binding site (Figure 3B). These results indicate that ANR is an activator of glpT gene expression, and it contributes to elevation of GlpT expression during anaerobic growth of P. aeruginosa.

FIGURE 3.

Sequence of the upstream glpT region and identification of ANR binding site and glpT transcriptional start site. (A) DNase I footprinting of the glpT promoter region. A 6-FAM-labeled DNA fragment was incubated in the presence or absence of ANR (30 pmol) and subjected to DNase I digestion. The fluorescence intensities of the DNA fragments (y-axis) are plotted relative to their size in bases (x-axis). One region (outlined by the dashed line) was protected from DNase I digestion in the presence of 30 pmol ANR protein. (B) Mapping of ANR binding site and glpT transcriptional start site on the glpT upstream region. The region protected from DNase I digestion is indicated by the box. Numbers indicate relative positions to the transcriptional start site.

Fosfomycin is More Active Under Anaerobic Conditions to not Only PAO1 but Also Another Clinical Isolate that Exhibits a Promoted Biofilm Phenotype

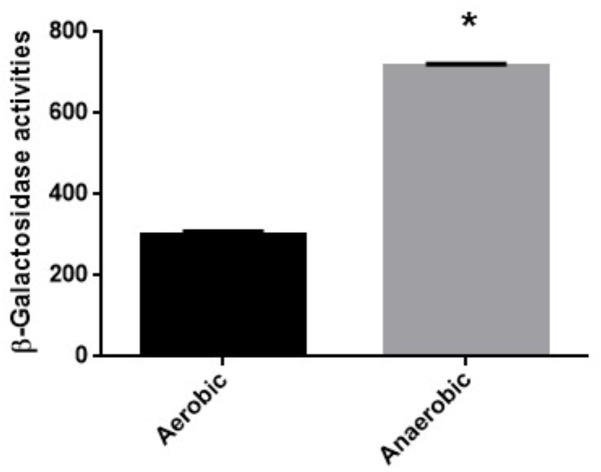

We also determined MICs of fosfomycin in a clinical isolate designated Ps.a-682 that highly forms biofilm when cultured under aerobic or anaerobic conditions since biofilm closely associates with bacterial virulence (Alhede et al., 2014). Therefore, we got interested in Ps.a-682 for this study. As well as PAO1, Ps.a-682 exhibited a fourfold lower MIC during anaerobic cultures compared to aerobic cultures (MICs: 16 mg/L for anaerobically grown cells vs. 64 mg/L for aerobically grown cells; diameters of inhibitory ring: 21 ± 2 mm for anaerobically grown cells vs. 15 ± 1 mm for aerobically grown cells) (Table 3). We also measured promoter activity of glpT by using the lacZ reporter plasmid, pBBRglpT(Ps.a-682)-P in Ps.a-682 when aerobically and anaerobically grown. A LacZ expression from the glpT promoter in cells grown anaerobically was higher than that in cells grown aerobically, which is similar to the results of the experiment with PAO1 (Figure 4). In addition, we determined sequences of the anr open reading frame and region upstream of glpT gene in Ps.a-682. These sequences were >90% identical to those of PAO1, then the region sequence in PAO1 protected from DNase I digestion including the (TTCAT-ttac-GAAAA) site where ANR is proposed to bind was completely conserved in Ps.a-682. These observations suggest that fosfomycin is more active under anaerobic conditions to not only PAO1 but also probably other P. aeruginosa strains, in which both glpT including its promoter and anr are conserved.

FIGURE 4.

β-Galactosidase activities of Ps.a-682 containing pBBRglpT(Ps.a.-682)-P, the lacZ reporter plasmid grown under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Data plotted are the means from three independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviations, ∗P< 0.01. Asterisks denote significance for values of glpT promoter activity in Ps.a-682 cultured under anaerobic conditions relative to those under aerobic conditions.

Discussion

In our previous studies on E. coli, we showed that expression of both glpT and uhpT which encode transporters contributing to fosfomycin uptake is elevated via an activation of FNR, a global anaerobic regulator when anaerobically grown, which leads to increased susceptibility under anaerobic conditions (Kurabayashi et al., 2015b, 2017). In this study, we found that P. aeruginosa also becomes more susceptible to fosfomycin during anaerobic cultures as well as E. coli (Table 3), then expression of glpT and intracellular level of fosfomycin are elevated by following activation of ANR, an anaerobic regulator of P. aeruginosa (Figures 1–4) while uhpT and fnr are absent on P. aeruginosa chromosome (Stover et al., 2000; Castaneda-Garcia et al., 2009). Similar to FNR of E. coli, ANR carries a [4Fe–4S] cluster in the active center, and they form an active dimer in the absence of oxygen (Yoon et al., 2007). They bind to an identical DNA sequence (TTGAT-N4-ATCAA) although glpT including its region upstream in PAO1 has a low sequence identity (<50%) to that in E. coli (Winteler and Haas, 1996; Yoon et al., 2007). GlpR blocks the transcription of glpT while FosA is an enzyme to inactivate fosfomycin. We showed that these productions are unlikely affected by oxygen depletion (Figure 2A). Inactivation of cyaA and ptsI decreases susceptibility to fosfomycin in E. coli. However, we note that these gene products do not contribute to the susceptibility in P. aeruginosa (Castaneda-Garcia et al., 2009).

Glycerol-3-phosphate is a native substrate of GlpT transporter, and it is a sole carbon source for growth (Argast et al., 1978; Kurabayashi et al., 2014). In particular, E. coli is also able to use this compound as an electron donor for anaerobic respiration, where the electron is released in a conversion to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by anaerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GlpABC) and transferred to the terminal reductases via a menaquinone carrier (Varga and Weiner, 1995; Unden and Bongaerts, 1997). These literatures may convince us that E coli increases the storage of glycerol-3-phosphate by elevating GlpT production to sustain its fitness under anaerobic conditions. On the other hand, there is an idea that contribution of GlpT to fitness in P. aeruginosa is less than that in E. coli although metabolism involving glycerol-3-phosphate is relatively less studied in P. aeruginosa (Castaneda-Garcia et al., 2009). P. aeruginosa has a more versatile capability for carbon utilization than E. coli. Indeed, glycerol-3-phosphate supplement does not promote the cell growth when cultured even in minimal medium containing an alternative carbon source such as glucose or glycerol (Castaneda-Garcia et al., 2009). In addition, it is unlikely that it uses glycerol-3-phosphate for anaerobic respiration because it lacks menaquinone and GlpABC while glycerol-3-phosphate may be still able to be used for aerobic respiration involving aerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase encoded by glpD (Schweizer and Po, 1994). However, transcriptome studies showed that the expression of glpD is higher in primary strains isolated from CF patients than that of strains grown in laboratory medium, implying that GlpD might contribute to virulence of P. aeruginosa during chronic respiratory infections (Daniels et al., 2014; Son et al., 2007), which does not exclude a possibility that glycerol-3-phosphate metabolism associated with GlpT-mediated transport participates in the oxygen-limited lifestyle during infection.

The in vitro antimicrobial tests according to a guideline of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) suggested that MICs of fosfomycin are very high for most of P. aeruginosa strains including clinical isolates (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2011), suggesting its low efficacy to this bacterium. The in vitro antibacterial activity in common cases was evaluated in bacteria when cultured aerobically. However, P. aeruginosa is often under oxygen-depleted conditions during infection, for instance, when it forms a poly-microbial complex termed biofilm in patients suffering from chronic respiratory infectious diseases, such as CF (Singh et al., 2000). Therefore, data of in vitro CLSI test might underestimate the in vivo efficacy of fosfomycin. Some of in vitro studies showed that most of antimicrobials including tobramycin and ciprofloxacin that are commonly used for treatment of P. aeruginosa infections are less effective under anaerobic conditions (Bryant et al., 1992; Morrissey and Smith, 1994; Kohanski et al., 2010), which is one of reasons why bacteria in biofilm are hard to be completely expelled. Thus, these literatures encourage us to use fosfomycin for treatment of chronic biofilm infection caused by P. aeruginosa although P. aeruginosa still produces glutathione-S-transferase to inactivate fosfomycin which is encoded by fosA on the chromosome.

Recently, a combination therapy using fosfomycin together with tobramycin, an aminoglycoside is being proposed for treatment of airway infections caused by bacteria including typically P. aeruginosa in CF patients (McCaughey et al., 2012; Diez-Aguilar et al., 2015). It is expected to confer a synergistic bactericidal activity to P. aeruginosa because fosfomycin addition reduced transcripts of narG/H genes which encode nitrate reductase subunits being essential for anaerobic nitrate respiration when grown with tobramycin although the molecular mechanism has still been unknown (McCaughey et al., 2013). This literature suggests that the co-drug treatment is effective to P. aeruginosa settled in biofilm sites probably under oxygen-depleted conditions by inhibiting the nitrate respiration in addition to the innate antimicrobial activity of these drugs such as inhibition of cell-wall and protein syntheses. In other works, administration of fosfomycin together with β-lactams such as imipenem is expected to synergistically increase the bactericidal activity to P. aeruginosa by blocking peptidoglycan (PG) recycling (Borisova et al., 2014; Hamou-Segarra et al., 2017).

Fosfomycin increasingly interests as an alternative option for treatment of infections, particularly caused by refractory strains as multi-drug resistant P. aeruginosa (MDRP) while a shortage of new antimicrobial agents becomes a critical issue at present. We believe that this study will contribute to provide extensive information to make fosfomycin treatment more effective to P. aeruginosa infection rising a serious health issue in worldwide.

Author Contributions

All of the authors designed the research. HH and KK performed the research. HH, KK, KT, and HT analyzed the data; HH, KT, and HT wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was kindly supported by JSPS KAKENHI “Grantin-Aid for Young Scientists (B)” Grant Number 17K17631, JST program; “Improvement of Research Environment for Young Researchers,” Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology (Gunma University Operation Grants), the Yakult Bioscience Research Foundation, the Takeda Science Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Research Grant, and Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from Japan Agency Research and Development, AMED.

References

- Alhede M., Bjarnsholt T., Givskov M., Alhede M. (2014). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: mechanisms of immune evasion. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 86 1–40. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800262-9.00001-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloush V., Navon-Venezia S., Seigman-Igra Y., Cabili S., Carmeli Y. (2006). Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors and clinical impact. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 43–48. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.43-48.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argast M., Ludtke D., Silhavy T. J., Boos W. (1978). A second transport system for sn-glycerol-3-phosphate in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 136 1070–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner F. R., Plunkett G., III, Bloch C. A., Perna N. T., Burland V., Riley M., et al. (1997). The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277 1453–1462. 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova M., Gisin J., Mayer C. (2014). Blocking peptidoglycan recycling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa attenuates intrinsic resistance to fosfomycin. Microb. Drug Resist. 20 231–237. 10.1089/mdr.2014.0036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant R. E., Fox K., Oh G., Morthland V. H. (1992). Beta-lactam enhancement of aminoglycoside activity under conditions of reduced pH and oxygen tension that may exist in infected tissues. J. Infect. Dis. 165 676–682. 10.1093/infdis/165.4.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K. (2012). Antimicrobial agents targeting bacterial cell walls and cell membranes. Rev. Sci. Tech. 31 43–56. 10.20506/rst.31.1.2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadaban M. J. (1976). Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104 541–555. 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassir N., Rolain J. M., Brouqui P. (2014). A new strategy to fight antimicrobial resistance: the revival of old antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 5:551. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda-Garcia A., Rodriguez-Rojas A., Guelfo J. R., Blazquez J. (2009). The glycerol-3-phosphate permease GlpT is the only fosfomycin transporter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol 191 6968–6974. 10.1128/JB.00748-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2011). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 20th Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M 100-S21. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels J. B., Scoffield J., Woolnough J. L., Silo-Suh L. (2014). Impact of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase on virulence factor production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can. J. Microbiol. 60 857–863. 10.1139/cjm-2014-0485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Aguilar M., Morosini M. I., Tedim A. P., Rodriguez I., Aktas Z., Canton R. (2015). Antimicrobial activity of fosfomycin-tobramycin combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates assessed by time-kill assays and mutant prevention concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 6039–6045. 10.1128/AAC.00822-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge S. J., Davis R. W. (1989). Position and density effects on repression by stationary and mobile DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 3 185–197. 10.1101/gad.3.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Irvine A. S., Meng W., Guest J. R. (1996). FNR-DNA interactions at natural and semi-synthetic promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 19 125–137. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.353884.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grif K., Dierich M. P., Pfaller K., Miglioli P. A., Allerberger F. (2001). In vitro activity of fosfomycin in combination with various antistaphylococcal substances. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48 209–217. 10.1093/jac/48.2.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamou-Segarra M., Zamorano L., Vadlamani G., Chu M., Sanchez-Diener I., Juan C., et al. (2017). Synergistic activity of fosfomycin, beta-lactams and peptidoglycan recycling inhibition against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 448–454. 10.1093/jac/dkw456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H., Inazumi Y., Masaki T., Hirata T., Yamaguchi A. (2005). Indole induces the expression of multidrug exporter genes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 55 1113–1126. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T. T., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Kutchma A. J., Schweizer H. P. (1998). A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212 77–86. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiby N. (2011). Recent advances in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis. BMC Med. 9:32. 10.1186/1741-7015-9-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye S., Watanabe T., Tsuruoka T., Kitasato I. (1989). An increase in the antimicrobial activity in vitro of fosfomycin under anaerobic conditions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 24 657–666. 10.1093/jac/24.5.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadner R. J., Winkler H. H. (1973). Isolation and characterization of mutations affecting the transport of hexose phosphates in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 113 895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski M. A., Dwyer D. J., Collins J. J. (2010). How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 423–435. 10.1038/nrmicro2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Hill D. S., Robertson G. T., Farris M. A., Roop R. M., II, et al. (1995). Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166 175–176. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurabayashi K., Hirakawa Y., Tanimoto K., Tomita H., Hirakawa H. (2014). Role of the CpxAR two-component signal transduction system in control of fosfomycin resistance and carbon substrate uptake. J. Bacteriol. 196 248–256. 10.1128/JB.01151-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurabayashi K., Hirakawa Y., Tanimoto K., Tomita H., Hirakawa H. (2015a). Identification of a second two-component signal transduction system that controls fosfomycin tolerance and glycerol-3-phosphate uptake. J. Bacteriol. 197 861–871. 10.1128/JB.02491-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurabayashi K., Tanimoto K., Fueki S., Tomita H., Hirakawa H. (2015b). Elevated Expression of GlpT and UhpT via FNR activation contributes to increased fosfomycin susceptibility in Escherichia coli under anaerobic conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 6352–6360. 10.1128/AAC.01176-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurabayashi K., Tanimoto K., Tomita H., Hirakawa H. (2017). Cooperative Actions of CRP-cAMP and FNR Increase the Fosfomycin Susceptibility of Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) by Elevating the Expression of glpT and uhpT under Anaerobic Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 8:426. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughey G., Gilpin D. F., Schneiders T., Hoffman L. R., McKevitt M., Elborn J. S., et al. (2013). Fosfomycin and tobramycin in combination downregulate nitrate reductase genes narG and narH, resulting in increased activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa under anaerobic conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 5406–5414. 10.1128/AAC.00750-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughey G., McKevitt M., Elborn J. S., Tunney M. M. (2012). Antimicrobial activity of fosfomycin and tobramycin in combination against cystic fibrosis pathogens under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. J. Cyst. Fibros. 11 163–172. 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey I., Smith J. T. (1994). The importance of oxygen in the killing of bacteria by ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin. Microbios 79 43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T. S., Egan M., Kazmierczak B. I. (2007). Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic colonization in cystic fibrosis patients. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 19 83–88. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3280123a5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obritsch M. D., Fish D. N., MacLaren R., Jung R. (2004). National surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates obtained from intensive care unit patients from 1993 to 2002. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 4606–4610. 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4606-4610.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2011). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front. Microbiol. 2:65. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby R. E., Fillgrove K. L., Beihoffer L. A., Armstrong R. N. (2005). Fosfomycin resistance proteins: a nexus of glutathione transferases and epoxide hydrolases in a metalloenzyme superfamily. Methods Enzymol. 401 367–379. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01023-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby R. E., Rife C. L., Fillgrove K. L., Newcomer M. E., Armstrong R. N. (2004). Phosphonoformate: a minimal transition state analogue inhibitor of the fosfomycin resistance protein, FosA. Biochemistry 43 13666–13673. 10.1021/bi048767h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawers R. G. (1991). Identification and molecular characterization of a transcriptional regulator from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 exhibiting structural and functional similarity to the FNR protein of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5 1469–1481. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber K., Krieger R., Benkert B., Eschbach M., Arai H., Schobert M., et al. (2007). The anaerobic regulatory network required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa nitrate respiration. J. Bacteriol. 189 4310–4314. 10.1128/JB.00240r-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. P., Po C. (1994). Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the glpD gene encoding sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 176 2184–2193. 10.1128/jb.176.8.2184-2193.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrocks A. D., Green J., Guest J. R. (1991). FNR activates and represses transcription in vitro. Proc. Biol. Sci. 245 219–226. 10.1098/rspb.1991.0113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. K., Schaefer A. L., Parsek M. R., Moninger T. O., Welsh M. J., Greenberg E. P. (2000). Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407 762–764. 10.1038/35037627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son M. S., Matthews W. J., Jr., Kang Y., Nguyen D. T., Hoang T. T. (2007). In vivo evidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nutrient acquisition and pathogenesis in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect. Immun. 75 5313–5324. 10.1128/IAI.01807-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover C. K., Pham X. Q., Erwin A. L., Mizoguchi S. D., Warrener P., Hickey M. J., et al. (2000). Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406 959–964. 10.1038/35023079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner K. H., Everett J., Trivedi U., Rumbaugh K. P., Whiteley M. (2014). Requirements for Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute burn and chronic surgical wound infection. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004518. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unden G., Bongaerts J. (1997). Alternative respiratory pathways of Escherichia coli: energetics and transcriptional regulation in response to electron acceptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1320 217–234. 10.1016/S0005-2728(97)00034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga M. E., Weiner J. H. (1995). Physiological role of GlpB of anaerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Cell Biol. 73 147–153. 10.1139/o95-018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winteler H. V., Haas D. (1996). The homologous regulators ANR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and FNR of Escherichia coli have overlapping but distinct specificities for anaerobically inducible promoters. Microbiology 142 685–693. 10.1099/13500872-142-3-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worlitzsch D., Tarran R., Ulrich M., Schwab U., Cekici A., Meyer K. C., et al. (2002). Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 109 317–325. 10.1172/JCI0213870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. S., Hennigan R. F., Hilliard G. M., Ochsner U. A., Parvatiyar K., Kamani M. C., et al. (2002). Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Dev. Cell 3 593–603. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00295-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. S., Karabulut A. C., Lipscomb J. D., Hennigan R. F., Lymar S. V., Groce S. L., et al. (2007). Two-pronged survival strategy for the major cystic fibrosis pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, lacking the capacity to degrade nitric oxide during anaerobic respiration. EMBO J. 26 3662–3672. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]