Abstract

Catalysis by the RNase H-superfamily members is generally believed to require only two Mg2+ ions coordinated by active-site carboxylates. By examining the catalytic process of B. Halodurans RNase H1 in crystallo, however, we find that the two canonical Mg2+ ions and an additional K+ fail to align the nucleophilic water for RNA cleavage. Substrate alignment and product formation require a second K+ and a third Mg2+, which replaces the first K+ and departs immediately after cleavage. A third transient Mg2+ has also been observed for DNA synthesis, but there it coordinates the leaving group instead of the nucleophile as in this hydrolysis reaction. These transient cations have no contact with enzymes. Other DNA and RNA enzymes that catalyze consecutive cleavage and strand transfer reactions in a single active site may likewise require cation trafficking coordinated by substrate.

Keywords: catalysis, phosphoryltransfer, nucleic acid, hydrolysis, metal ions

Introduction

Through the analysis of DNA synthesis in crystallo by time-resolved X-ray crystallography, our group has shown that binding of two canonical Mg2+ ions by DNA pol η is insufficient to initiate the reaction, and a third Mg2+ ion transiently bound to the incoming dNTP is required for catalysis 1,2. The question is whether capture of a transient third Mg2+ ion for catalysis is specific for DNA polymerase or a general requirement for all enzymes thought to use the two-metal-ion mechanism. Here we study ribonuclease H1 (RNase H1), which cleaves the RNA strand in RNA/DNA hybrids to remove RNA primers and resolve R-loops 3,4, as an enzyme unrelated to DNA pol η, to investigate whether additional cations are similarly required for RNA hydrolysis. RNase H1 has many homologues, including the RNA silencing factor Argonaute, PIWI, and many DNA transposases from HIV integrase to RAG1/2 recombinase 5–7, which all bind two Mg2+ ions (A and B) in the active site and catalyze an SN2 type nucleotidyltransfer reaction 8–11, and therefore may be expected to use a similar mechanism.

Taking a similar approach to studies of DNA polymerases 1,12,13, we crystallized wildtype (WT) RNase H1 complexed with an RNA/DNA hybrid in the presence of Ca2+ ions, which support enzyme-substrate complex formation but prevent chemical reaction. Replacement of Ca2+ by Mg2+ at pH 7.0 led to catalysis in crystallo, and using freeze-trapping, we characterized catalytic intermediates by X-ray crystallography 14. In our high-resolution structures, we find that K+ ions likely play catalytic roles in the RNA hydrolysis reaction. A transiently bound third Mg2+, although difficult to observe, is indeed involved in RNase H1 catalysis, but it coordinates the nucleophile instead of the leaving group as in the DNA synthesis reaction.

Results

Substrate design and RNA cleavage in crystallo

RNase H1 is a non-sequence specific nuclease and can slide along the hybrid duplex in RNase H1-RNA/DNA co-crystals, resulting in mixed positional registers 8,15. Based on the minimal recognition site of four ribonucleotides, we designed a 6 bp substrate with four RNA/DNA base pairs in the center and one DNA/DNA base pair at each end (Fig. 1a), which led to a unique binding and cleavage site by RNase H1 and an end-to-end stacking of the hybrid nucleic acids. These co-crystals diffracted X-rays up to 1.27 Å resolution, compared to the previous best value of 1.65 Å 8,15.

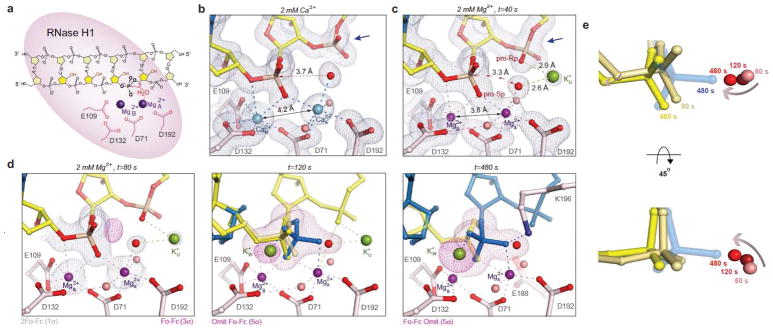

Figure 1.

RNA hydrolysis by RNase H1. (a) Diagram of the RNA/DNA hybrid for in crystallo cleavage. (b, c) The Ca2+- (light blue) and Mg2+-bound (purple) RNase H1 ES complexes. The blue arrowheads mark the 3′-downstream phosphate. (d) RNase H1 in crystallo catalysis at t=80, 120 and 480 s after soaking in 2 mM MgCl2. The substrate (yellow) and product (blue) are shown with grey 2Fo-Fc and pink Fo-Fc maps. The Fo-Fc maps at 120 and 480 s were calculated with the scissile phosphate omitted. (e) Substrate alignment during the reaction, with the earlier time points in the lighter colors.

Structures of WT RNase H1-RNA/DNA complexes with two Ca2+ ions bound and with Ca2+ depleted by soaking crystals in an EGTA buffer were determined (Fig. 1b and S1a, Table 1 and Supplementary Data Set 2). Without Ca2+, the metal ion-binding sites (A and B) were occupied by K+ ions from the soaking buffer, and the active-site carboxylates E109 and D71 were disordered or assumed a different conformation (Fig. S1b). To initiate RNA cleavage, Ca2+-depleted crystals were transferred to a buffer containing 2 mM Mg2+ and 200 mM K+ at 22°C (Fig. S1a). After soaking for 40 to 600 s, the crystals were cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen (LN2) to stop the reaction at regular time intervals, and stored for analysis by X-ray diffraction. Reactions in crystallo are usually 20–100 times slower than in solution 1,2,12 probably because of limited Brownian motion.

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

RNase H1WT - substrate complexes (Fig. 1b and 1c)

| Ca2+ bound | Mg2+ bound | |

|---|---|---|

| PDB 6DMN | PDB 6DMV | |

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | C 1 2 1 | C 1 2 1 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 81.5, 37.7, 62.0 | 81.4, 37.8, 62.0 |

| a, b, γ (°) | 90, 95.9, 90 | 90, 96.3, 90 |

| Resolution (Å)1 | 20.0 - 1.27 (1.29 - 1.27) | 20.0 - 1.53 (1.56 - 1.52) |

| Rpim 1 | 0.051 (0.352) | 0.053 (0.866) |

| Rsym or Rmerge 1 | 0.074 (0.51) | 0.077 (>1.0) |

| I/σ (I)1 | 10.8 (2.1) | 10.7 (0.97) |

| CC1/2 1 | (0.727) | (0.373) |

| Completeness (%)1 | 94.3 (92.9) | 99.3 (99.7) |

| Redundancy1 | 3.0 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.7) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å)1 | 18.0 - 1.27 | 19.2 - 1.52 |

| No. reflections1 | 46729 | 28093 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 15.0/17.1 | 16.1/18.2 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein / RNA/ DNA | 2088 / 144 / 121 | 2022 / 122 / 121 |

| Me2+ | 2 Ca2+ | 2 Mg2+ |

| Me+ 4 | 1 K+ | 2 K+ |

| Halides4 | 4 I− | 4 I− |

| Water/ Solvent | 170 / 28 | 175 / 32 |

| Occupancy | ||

| RS: PS | 1.0 : 0 | 1.0 : 0 |

| A site | 0.75 Ca2+ | 1.0 Mg2+ |

| B site | 0.90 Ca2+ | 1.0 Mg2+ |

| U site | 0 | 0.35 K+ |

| B-factors | ||

| Macromolecules | 25.3 | 28.5 |

| MeA / LigA2 | 17.7 / 19.8 | 24.2 / 29.2 |

| MeB / LigB2 | 16.5 / 18.2 | 24.5/ 24.3 |

| MeU / LigU2 | NA | 38.2 / 34.5 |

| Solvent3 | 42.2 | 35.0 |

| R.m.s deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.00 | 1.06 |

Data in the highest resolution shell is shown in the parenthesis.

B-factors of metal ions and their protein, solvent, and nucleotide ligands.

Water, ethylene glycol and glycerol

B factors and occupancies are not listed for non-catalytic monovalent cations and halides

At t=40 s, binding of Mg2+ in the A and B sites was nearly 100% complete, and the four catalytic carboxylates (D71, E109, D132 and D192) and scissile phosphate became fully ordered. However, there was no reaction and no product (Fig. 1c, Table 1). The A-site Mg2+ (Mg2+A) has six ligands in an ideal octahedral geometry, while Mg2+B has five coordinating ligands in a non-ideal coordination geometry as observed with the active-site mutants 8. Mg2+A and Mg2+B are 3.8 Å apart and thus 0.4 Å closer to each other than Ca2+ ions (Fig. 1b) or two Mg2+ ions bound to active-site mutants 8,15. The nucleophilic water molecule coordinated by Mg2+A is also 0.3 Å closer to the scissile phosphate than when coordinated by Ca2+A. Most notably, only in the presence of Mg2+, a K+ ion (K+u for occupying the U site) appeared and coordinated the nucleophilic water and the phosphate 3′ to the scissile bond, which assumed an unusual β torsion angle (Fig. 1c). These differences explain why Ca2+ inhibits RNase H1 16 and also the observation that sulfur replacement of the pro-Rp oxygen of the 3′-phosphate, which coordinates K+u, reduces the catalytic rate of E. coli RNase H1 by seven fold 17. Despite binding of the two Mg2+ and the presence of K+u, the nucleophilic water is misaligned by 20° and too distant (3.3 Å) for the in-line nucleophilic attack (Fig. 1c).

At t=80 s, a small fraction of substrate underwent reaction as evidenced by the appearance of electron density for the new P-O bond (Fig. 1d, Table 2), although the misaligned substrate form remained dominant. At t=120 s, catalysis reached a point, where 65% substrate and 35% product co-existed in the inverted scissile phosphate configuration. With only minute changes of the active site residues or A and B Mg2+ ions, the majority of nucleophile and scissile phosphate (~40% or 2/3 of the 65% substrate) became well aligned and within 3.0 Å for the in-line nucleophilic attack (Fig. 1d, e). After the reaction reached a plateau, e.g. at t=480 s, the cleaved 5′-phosphate became stabilized by K196, which was disordered in the enzyme-substrate (ES) complex. The freed 3′-OH together with the ribose changed its conformation from 3′ endo to 2′ endo and moved away from the phosphate product (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, alignment of the nucleophile and scissile phosphate occurred gradually over the reaction time and concurrently with product formation (Fig. 1e). The question is what drives substrate alignment and reaction.

Table 2. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| 80 s | 120 s | 480 s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB 6DO8 | PDB 6DO9 | PDB 6DOA | |

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | C 1 2 1 | C 1 2 1 | C 1 2 1 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 81.3, 37.8, 62.1 | 81.3, 37.8, 62.5 | 81.7, 37.9, 62.7 |

| a, b, γ (°) | 90, 96.2, 90 | 90, 96.2, 90 | 90, 96.7, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) 1 | 20.0 - 1.42 (1.44 - 1.42) | 20.0 - 1.36 (1.38 - 1.36) | 50.0 - 1.48 (1.51 - 1.48) |

| Rpim 1 | 0.031 (0.830) | 0.051 (>1.0) | NA |

| Rsym or Rmerge 1 | 0.046 (>1.0) | 0.073 (>1.0) | 0.053 (0.67) |

| I/σ (I) 1 | 19.6 (0.80) | 12.7 (0.80) | 17.6 (1.38) |

| CC1/2 1 | (0.348) | (0.173) | NA |

| Completeness (%) 1 | 96.9 (90.0) | 98.2 (84.8) | 99.5 (99.4) |

| Redundancy 1 | 3.1 (2.5) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.1 (2.7) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å)1 | 19.2 - 1.42 | 19.9 - 1.36 | 31.1 - 1.48 |

| No. reflections1 | 34740 | 40176 | 32224 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 15.0 /16.8 | 15.4 / 17.6 | 15.6 / 18.2 |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein / RNA/ DNA | 2054 / 122 / 121 | 2048 / 147 / 121 | 2096 / 135 / 121 |

| Me2+ | 2 Mg2+ | 2 Mg2+ | 2 Mg2+ |

| Me+ 4 | 2 K+ | 3 K+ | 3 K+ |

| Halides4 | 4 I− | 4 I− | 4 I− |

| Water/ Solvent | 191 / 37 | 187 / 50 | 196 / 55 |

| Occupancy | |||

| RS: PS | 0.80 : 0 | 0.65 : 0.35 | 0.35 : 0.65 |

| A site | 1.0 Mg2+ | 1.0 Mg2+ | 1.0 Mg2+ |

| B site | 1.0 Mg2+ | 1.0 Mg2+ | 1.0 Mg2+ |

| U site | 0.30 K+ | 0.25 K+ | 0.10 K+ |

| W site | 0 | 0.25 K+ | 0.35 K+ |

| B-factors | |||

| Macromolecules | 25.1 | 26.6 | 22.6 |

| MeA / LigA2 | 19.3 / 25.6 | 20.9 / 32.5 | 17.0 / 20.3 |

| MeB / LigB2 | 19.3 / 20.7 | 21.5 / 25.7 | 14.7 / 18.3 |

| MeU / LigU2 | 28.8 / 30.8 | 28.2 / 27.7 | 24.9 / 23.8 |

| MeW / LigW2 | NA | 24.9 / 19.1 | 18.4 / 16.0 |

| Solvent3 | 39.8 | 42.3 | 36.8 |

| R.m.s deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.98 | 1.28 | 1.14 |

Data in the highest resolution shell is shown in the parenthesis.

B-factors of metal ions and their protein, solvent, and nucleotide ligands.

Water, ethylene glycol and glycerol

B factors and occupancies are not listed for non-catalytic monovalent cations and halides

Monovalent cations are necessary for RNase H1 catalysis

Accompanying the product formation of RNA hydrolysis, a second K+ ion appeared at the W site (K+W) and contacted the pro-Rp oxygen of the scissile phosphate (Fig. 1d). The appearance of K+W and reaction products were correlated as shown in the unbiased Fo-Fc map, and occupancies of both increased with the reaction time until reaching a plateau at t=200 s (Fig. 2a). To determine whether K+ is essential for the reaction, we varied K+ concentrations in the in crystallo reaction and found that both the K+U occupancy and the cleavage product (at t=120 s) decreased significantly with decreasing K+ concentrations (Fig. 2b).

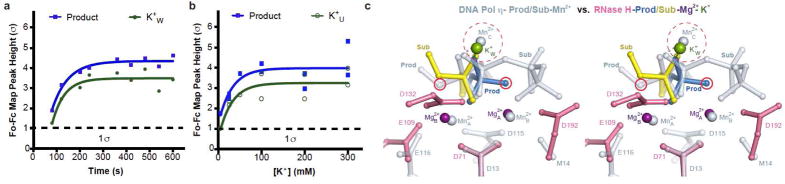

Figure 2.

Essential monovalent cations in the RNase H1 reaction. (a) Correlated appearance of the W-site K+ and RNA cleavage product over the reaction time course. (b) Occupancy of K+U is K+ concentration dependent and correlated with product formation. All data points shown in the plot were collected at t= 120s. (c) Comparison of the W-site K+/Rb+ in RNase H1 and C-site Mn2+ in DNA pol η. The active sites of the two enzymes are superimposed and shown in stereo. The nucleophiles are circled in red.

To verify the locations of monovalent cations, we replaced K+ with Rb+ in the in crystallo reaction buffer to take advantage of the anomalous diffraction of Rb+. Rb+ supports RNase H1 catalysis in solution as does K+ (Fig. S2a). By analyzing the anomalous difference Fourier maps, we detected Rb+U, Rb+W, and a third Rb+ at the V site (Rb+V) (Fig. S2b–c). The U and V sites are only 2.4 Å apart and too close for simultaneous occupancy. Rb+U disappeared in inverse correlation to product formation, while Rb+V appeared in the product state only and was eventually displaced by the ordered K196 in the product state (Fig. 1d).

The W site was vacant in the ES complex and became occupied by K+ or Rb+ in proportion to the amount of product formed (Fig. 2a). When structures of DNA Pol η and RNase H1 were superimposed on the scissile phosphate and two canonical Mg2+ ions, the third Mg2+C (or Mn2+C), which is absolutely required for the DNA synthesis reaction, was within 1 Å of K+w (Fig. 2c, FigS2e). Despite the reversed reactions (nucleic acid synthesis versus degradation) and opposite positions of the nucleophiles, Me2+C in Pol η and K+w/Rb+w in RNase H1 appear concurrently with product formation, and both coordinate the leaving groups without contacting the enzymes and possibly neutralize the transition state.

The conserved third Me2+ in RNase H1 catalysis

To determine the requirement of divalent cations for RNase H1 catalysis, we titrated Mg2+ in the in crystallo reaction and found that the Mg2+ concentration needed to occupy the canonical A and B sites was clearly lower than that required for optimal catalysis (Fig. 3a). The A and B site were 100% occupied by 1 mM Mg2+ at t=40 s, but no reaction product was detected (Fig. 3a). With increasing Mg2+ concentrations, the reaction products began to increase until plateauing at 20 mM Mg2+, while the occupancy of the A and B sites remained unchanged. The disparity suggests that RNase H1 catalysis depends on additional weakly binding Mg2+ ions. However, no additional Mg2+ was observed (Fig. S3a).

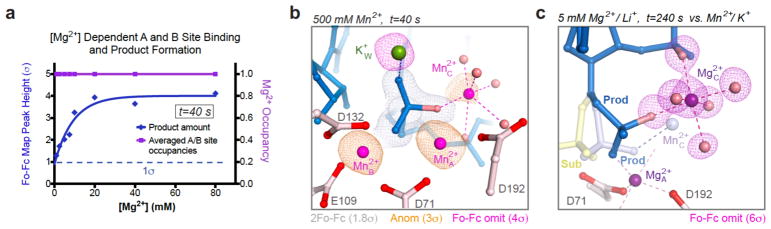

Figure 3.

Detection of a third Me2+ with WT RNase H1. (a) The A and B occupancies (magenta) and product formation (blue) require different Mg2+ concentrations. (b) Mn2+C was detected in 500 mM Mn2+ at t=40s with 100% product formation. The structure is shown with grey 2Fo-Fc, pink omit Fo-Fc and golden anomalous maps. (c) Mg2+C was observed upon product formation in the Li+/Mg2+ buffer and highlighted by the six coordinating ligands (four H2O) and the superimposed Fo-Fc map. Mg2+C and the 5′-phosphate product are shifted by ~1 Å relative to those in the K+/Mn2+ reaction (shown in lighter shades).

We then resorted to Mn2+, which supports RNase H activity (Fig. S3b) and facilitates detection because of its higher density of electrons than Mg2+, and anomalous diffraction 2. Varying Mn2+ concentrations from 2 to 100 mM in the in crystallo reactions, the disparity between A- and B-site Mn2+ binding and product formation was reproduced (Fig. S3c), although less pronounced than with Mg2+. A third and low-occupancy Mn2+ was observed occasionally upon product formation, but its binding site overlaps with and thus may be competed off by K196 in the product state (Fig. S3d). Only in 500 mM Mn2+ could we unequivocally detect the third Mn2+ (Mn2+C) with an occupancy of 0.30 at t=40 s, when the reaction was complete, while K196 remained disordered (Fig. 3b). Although high concentrations of Mn2+ in solution inhibit product release and reduce steady state kcat (Fig. S3b), a phenomenon known as attenuation 18, in crystallo an overdose of Mn2+ stabilized the product state as the reaction was limited to a single turnover. Mn2+C is coordinated by four water ligands, the pro-Rp oxygen atom of the 3′ phosphate, and the nucleophilic oxygen atom that become the 5′-phosphate product. One of the water ligands of Mn2+C overlaps with K+U, which explains the disappearance of K+U when the reaction occurs. Another water ligand of Mn2+C overlaps with K+V, suggesting that K+V may replace Me2+C before K196 and the associated E188 clear the cations out (Fig. S3d, Video 1).

The third Mg2+ (Mg2+C) was also observed in an in crystallo reaction with 5 mM Mg2+ and 200 mM Li+ (Fig. 3c). Li+ is a poor substitute of K+ for RNase H1 catalysis in solution (Fig. S2a), because Li+ and Mg2+ compete for the same binding sites. Li+ slowed down Mg2+ binding in the A and B sites before reaction took place (Fig. S2d), and after product formation Li+ may fail to displace Mg2+C via the V-site. Mg2+C (observed with Li+) and Mn2+C share the same six coordination ligands and are nearly superimposable except that Mg2+C together with the 5′-phosphate product is shifted by ~ 1.0 Å from the active site (Fig. 3c).

Verification of K+ and Mg2+ requirement with mutant RNases H1

To avoid displacement of Me2+C by the protein sidechains, we replaced K196 and E188 with alanine. E188 forms a salt bridge with K196 in the product state (Fig. S3b) and is also involved in catalysis 8,15. RNaseH1K196A and RNaseH1E188A are both defective in catalysis in the presence of Mg2+, but these defects were rescued by Mn2+ (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Data Set 1). Even WT RNaseH1 is significantly activated by Mn2+, which is not as stringent as Mg2+ in coordination requirement and probably tolerates the five-liganded B-site much better than Mg2+. In the presence of 4 mM Mn2+, the third Mn2+ (Mn2+C) was detected with RNaseH1E188A as early as 40 s when product began forming. By 240 s, when the reaction was nearly complete, Mn2+C together with K+W was unmistakably present in the product complexes of both RNaseH1K196A and RNaseH1E188A (Fig. 4b, Fig. S4a), and K196 was disordered in the absence of E188.

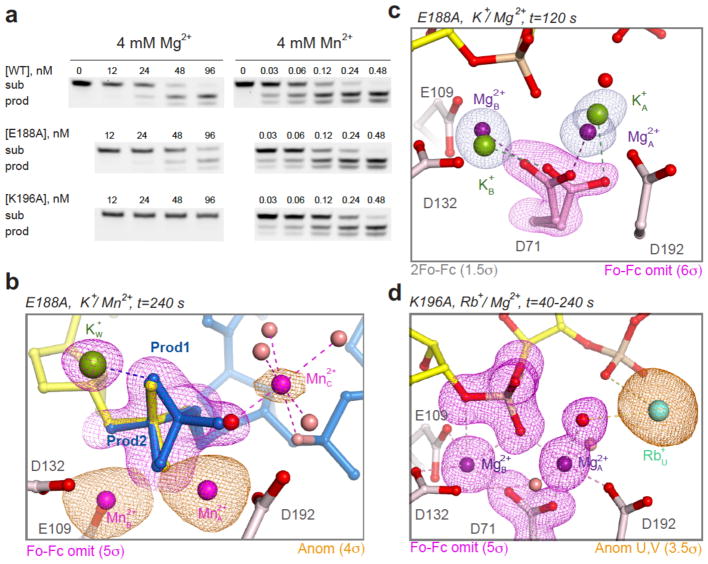

Figure 4.

Confirmation of Me2+C using E188A and K196A mutant RNases H1. (a) In solution RNA cleavage of RNA/DNA hybrids (similar to those used in crystallization, see Methods) by WT and mutant RNases H1 with Mg2+ or Mn2+. Images were visualized with a Typhoon FLA 9500 biomolecular imager (see Methods). Uncropped gel images are presented in Supplementary Data Set 1. (b) RNaseH1E188A in crystallo reaction with 4 mM Mn2+ confirmed the appearance of Mn2+C with product formation (blue). The golden anomalous map and pink Fo-Fc omit map are superimposed. (c) Delayed binding of A and B-site Mg2+ ions by RNaseH1E188A and absence of K+U for 120 s. (d) The in crystallo catalysis by RNaseH1K196A revealed that A- and B-site Mg2+ binding took place in 40 s, but the reaction did not occur for more than 240 s.

The roles of E188 and K196 extend beyond facilitating Mn2+C removal and product release. Reactions in crystallo with Mg2+ and RNaseH1E188A revealed that binding of two canonical Mg2+ ions was delayed. The lingering K+ ions in the A and B sites were easily detected because the catalytic carboxylate D71 partially retained the K+-binding conformation after 120 s (Fig. 4c, S1b). Without A- and B-site Mg2+, K+U was absent too. It took almost 200 s for Mg2+ to fully occupy the A and B sites instead of 40 s as with WT RNase H1 (Fig. S5a). Afterwards, the reaction proceeded similarly to WT, and by t=360 s Mg2+C appeared with the products in the same position as in the WT RNase H1/Li+ reaction (Fig. S5b–c).

Reactions in crystallo with RNaseH1K196A confirmed the disparity between the A- and B-site Mg2+ binding, which took less than 40 s, and product formation, which was not detectable for more than 240 s (Fig. 4d). For more than 200 s, two Mg2+ and a K+ occupied A, B and U sites as with WT RNase H1, but there was no sign of reaction. Using Rb+, we detected concurrent W-site occupancy and product formation after t=480 s. Without K196, both recruitment of Me+ to the W site and reaction were delayed, and the cleaved 5′-phosphate product was inverted and adopted the same conformation as the substrate form (Fig. S4b). The inversion became obvious when the reaction was complete at t=1800 s. Even in the Mn2+-dependent reactions, a fraction of the 5′ phosphate products were inverted without an ordered K196 (Fig. 4b, Fig. S4a). RNA hydrolysis, however, was readily detected by visualizing the cleaved 3′-ribose product, which moved out of the active site by ~7 Å (Fig. S4b). K196 is conserved throughout the RNase H superfamily (Fig. S4c) 19,20, and its role in RNA hydrolysis appears analogous to that of R61 of Pol η in DNA synthesis 1,2. K196 may help aligning RNA substrate to capture the transient cations for catalysis (Fig. 4d) and facilitating removal of the cations for product turnover.

Discussion

Comparison of RNase H1 hydrolysis and DNA synthesis

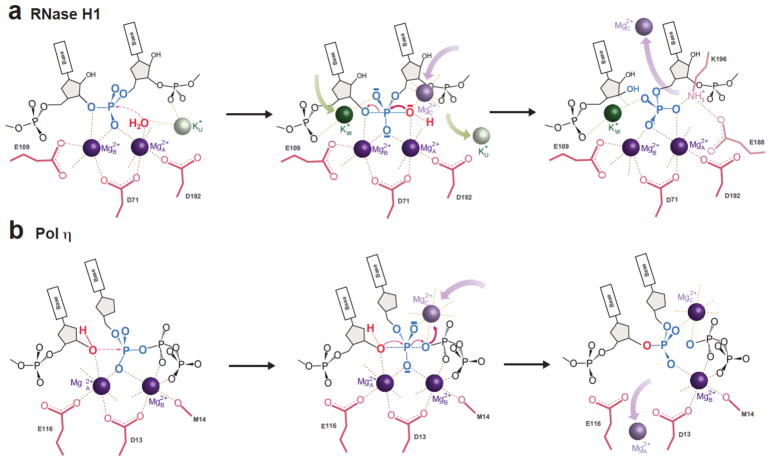

Both DNA synthesis and RNA hydrolysis reactions require a transiently bound third Me2+, but RNA hydrolysis, with mono- and di-valent cation trafficking, is much more complicated (Fig. 5). Upon binding of A- and B-site Mg2+ ions, Pol η aligns the DNA and an incoming dNTP perfectly for the synthesis reaction 1. In contrast, RNase H1 fails to align the substrates (Fig. 1c–e). Substrate alignment and catalysis by RNase H1 require the appearance of K+W to coordinate the scissile phosphate, and transiently bound Mg2+C to replace K+U and synergize with Mg2+A to activate the nucleophilic water for nucleophilic attack. K+W and Mg2+C may also neutralize the negative charge built up in the transition state during RNA hydrolysis. Although the transiently bound Me2+C is located on opposite sides of the scissile phosphate and coordinates attacking versus leaving group in the two reactions, it may be essential for driving the reaction in both cases (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Catalytic mechanism of RNase H1. (a) Diagram of RNA hydrolysis catalyzed by RNase H1. ES complex formation with two Mg2+ and one K+ ions; binding of two additional cations, K+w and Mg2+C (replacing K+U), for substrate alignment and product formation; and release of Mn2+C and K+v facilitated by K196 and E188. (b) Cation trafficking in the DNA synthesis reaction is similar except for (1) the perfect substrate alignment without Me2+C in Pol η, (2) Me2+C coordinating the leaving group in Pol η vs the nucleophile in RNase H1, and (3) no detectable K+ in DNA synthesis.

A significant difference between the two reactions is the nature of the nucleophiles. In DNA polymerase, the 3′-OH is docked via DNA, which interacts extensively with the enzyme, but the nucleophilic H2O for RNA hydrolysis is a free entity. The K+ and Mg2+ trafficking in the RNA hydrolysis reaction likely provides additional energy to align and deprotonate the nucleophilic H2O 21. For product release, spontaneous departure of Me2+A appears sufficient in the DNA synthesis reaction 1,2, but in the RNA hydrolysis reaction the A and B-site Mg2+ remain, while Mg2+C is quickly replaced by K+V and K196 (Fig. 5).

We suggest that these results demand a reconsideration of reaction mechanisms. The conventional transition state theory is now over 80 years old, but there is a dearth of experimental observations for the actual conversion of reactants to products. Enzymes are assumed to accelerate reaction rates by stabilizing transition states as intermediate configurations between substrate and product, and thus lowering the energy barrier to product formation. However, we find little movement of the catalytic residues or the A and B-site Me2+ ions during reactions catalyzed by RNase H1 or DNA pol η. Instead, each reaction acquires cations transiently bound to substrate only (Fig. 5). Rather than electrostatic reorganization or hydrogen tunneling 22–24, we have observed distinct forms of cation trafficking for substrate alignment and overcoming energy barriers to product formation.

K+ is the most abundant monovalent cation in cells. Monovalent salts are known for their roles in establishing membrane potential, osmoregulation and integrity of macromolecular structures 25,26. K+ and Na+ ions have also been noted for coordinating ligands in various ATPases and GTPases 27,28. However, monovalent cations have not been reported to participate directly in catalysis. Unlike Ca2+, Zn2+ or Mg2+, it is impossible to remove all Na+ and K+ during assays. Detailed and high-resolution analyses of in crystallo catalysis may be the only way to uncover catalytic roles for physiologically abundant salts and transiently associated ions.

We anticipate that cation trafficking and a transiently bound third Mg2+ ion are general features among the RNase H1 superfamily. Mg2+ cannot be replaced by protein sidechains because of the +2 charge and the stringent requirement for octahedral coordination. We have shown that the C-site Me2+ is highly selective in the DNA synthesis reaction 1,2. The distinct cation trafficking and different roles of the third Mg2+ in RNA cleavage and DNA synthesis shed light on how HIV-1 integrase and RAG1/2 recombinase, and other members of this superfamily, can catalyze consecutive strand cleavage and transfer reactions in a single active site.

Data availability

The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes: 6DMN, 6DMV, 6DO8, 6DO9, 6DOA, 6DOB, 6DOC, 6DOD, 6DOE, 6DOF, 6DOG, 6DOH, 6DOI, 6DOJ, 6DOK, 6DOL, 6DOM, 6DON, 6DOO, 6DOP, 6DOQ, 6DOR, 6DOS, 6DOT, 6DOU, 6DOV, 6DOW, 6DPP, 6DOX, 6DOY, 6DOZ, 6DP0, 6DP1, 6DP2, 6DP3, 6DP4, 6DP5, 6DP6, 6DP7, 6DP8, 6DP9, 6DPA, 6DPB, 6DPC, 6DPD, 6DPE, 6DPF, 6DPG, 6DPH, 6DPI, 6DPJ, 6DPK, 6DPL, 6DPM, 6DPN, 6DPO. Source data for Fig. 4a is available with the paper online. Other data and results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the help of D. Kaufman and L. Wise in RNase H1 protein preparation and co-crystallization. We thank L. Tabak for generous support of N.L.S., and R. Craigie, F. Dyda, M. Gellert and D. Leahy for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Intramural AIDS targeted Anti-Viral Program (IATAP) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK036144-11) to W. Y. and N.L.S., and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to N. S. (via L. Tabak).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

N.L.S. and W.Y. designed experiments, N.L.S. carried out experiments, N.L.S. and W.Y. interpreted results and wrote the paper.

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- 1.Nakamura T, Zhao Y, Yamagata Y, Hua YJ, Yang W. Watching DNA polymerase eta make a phosphodiester bond. Nature. 2012;487:196–201. doi: 10.1038/nature11181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao Y, Yang W. Capture of a third Mg(2)(+) is essential for catalyzing DNA synthesis. Science. 2016;352:1334–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tadokoro T, Kanaya S. Ribonuclease H: molecular diversities, substrate binding domains, and catalytic mechanism of the prokaryotic enzymes. FEBS J. 2009;276:1482–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ. Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J. 2009;276:1494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W, Steitz TA. Recombining the structures of HIV integrase, RuvC and RNase H. Structure. 1995;3:131–4. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowotny M. Retroviral integrase superfamily: the structural perspective. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:144–51. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MS, Lapkouski M, Yang W, Gellert M. Crystal structure of the V(D)J recombinase RAG1-RAG2. Nature. 2015;518:507–11. doi: 10.1038/nature14174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell. 2005;121:1005–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowotny M, et al. Structure of human RNase H1 complexed with an RNA/DNA hybrid: insight into HIV reverse transcription. Mol Cell. 2007;28:264–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steitz TA, Steitz JA. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6498–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang W, Lee JY, Nowotny M. Making and breaking nucleic acids: two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freudenthal BD, Beard WA, Shock DD, Wilson SH. Observing a DNA polymerase choose right from wrong. Cell. 2013;154:157–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamsen JA, et al. Time-lapse crystallography snapshots of a double-strand break repair polymerase in action. Nat Commun. 2017;8:253. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samara NL, Gao Y, Wu J, Yang W. Detection of Reaction Intermediates in Mg2+-Dependent DNA Synthesis and RNA Degradation by Time-Resolved X-Ray Crystallography. Methods Enzymol. 2017;592:283–327. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowotny M, Yang W. Stepwise analyses of metal ions in RNase H catalysis from substrate destabilization to product release. EMBO J. 2006;25:1924–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosta E, Yang W, Hummer G. Calcium inhibition of ribonuclease H1 two-metal ion catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3137–44. doi: 10.1021/ja411408x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haruki M, Tsunaka Y, Morikawa M, Iwai S, Kanaya S. Catalysis by Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI is facilitated by a phosphate group of the substrate. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13939–44. doi: 10.1021/bi001469+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keck JL, Goedken ER, Marqusee S. Activation/attenuation model for RNase H. A one-metal mechanism with second-metal inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34128–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanaya S. Enzymatic activity and protein stability of E. coli ribonuclease H. INSERM; Paris: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naumann TA, Reznikoff WS. Tn5 transposase active site mutants. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17623–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200742200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosta E, Nowotny M, Yang W, Hummer G. Catalytic mechanism of RNA backbone cleavage by ribonuclease H from quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8934–41. doi: 10.1021/ja200173a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warshel A, et al. Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3210–35. doi: 10.1021/cr0503106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamczyk AJ, Cao J, Kamerlin SC, Warshel A. Catalysis by dihydrofolate reductase and other enzymes arises from electrostatic preorganization, not conformational motions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14115–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111252108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klinman JP, Kohen A. Hydrogen tunneling links protein dynamics to enzyme catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:471–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051710-133623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodgkin AL, Keynes RD. Active transport of cations in giant axons from Sepia and Loligo. J Physiol. 1955;128:28–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang F. Mechanisms and significance of cell volume regulation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26:613S–623S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu X, Machius M, Yang W. Monovalent cation dependence and preference of GHKL ATPases and kinases. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:268–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gohara DW, Di Cera E. Molecular Mechanisms of Enzyme Activation by Monovalent Cations. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:20840–20848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.737833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes: 6DMN, 6DMV, 6DO8, 6DO9, 6DOA, 6DOB, 6DOC, 6DOD, 6DOE, 6DOF, 6DOG, 6DOH, 6DOI, 6DOJ, 6DOK, 6DOL, 6DOM, 6DON, 6DOO, 6DOP, 6DOQ, 6DOR, 6DOS, 6DOT, 6DOU, 6DOV, 6DOW, 6DPP, 6DOX, 6DOY, 6DOZ, 6DP0, 6DP1, 6DP2, 6DP3, 6DP4, 6DP5, 6DP6, 6DP7, 6DP8, 6DP9, 6DPA, 6DPB, 6DPC, 6DPD, 6DPE, 6DPF, 6DPG, 6DPH, 6DPI, 6DPJ, 6DPK, 6DPL, 6DPM, 6DPN, 6DPO. Source data for Fig. 4a is available with the paper online. Other data and results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.