Abstract

Over 25% of Persian Gulf War (PGW) veterans with Gulf War Illness (GWI) (chronic health complaints of undetermined etiology) developed GI symptoms (diarrhea and abdominal pain) and somatic complaints. Objectives: Our study objective was to determine if veterans with GWI and GI symptoms exhibit heightened patterns of somatic pain perception (hypersensitivity) across nociceptive stimuli modalities. Methods: Subjects were previously deployed GW Veterans with GWI and GI symptoms (n=53); veterans with GWI without GI symptom (n=47); and veteran controls (n=38). We determined pain thresholds for contact thermal, cold pressor, and ischemic stimuli. Results: Veterans with GWI and GI symptoms showed lower pain thresholds (p<0.001) for each stimulus. There was also overlap of somatic hypersensitivities among veterans with GI symptoms with 20% having hypersensitivity to all 3 somatic stimuli. Veterans with GWI and GI symptoms also showed a significant correlation between M-VAS abdominal pain ratings and heat pain threshold, cold pressor threshold, and ischemic pain threshold/tolerance. Discussion: Our findings show that there is widespread somatic hypersensitivity in veterans with GWI/GI symptoms that is positively correlated with abdominal pain ratings. In addition, veterans with somatic hypersensitivity that overlap have the greatest number of extraintestinal symptoms. These findings may have a translational benefit: strategies for developing more effective therapeutic agents that can reduce and/or prevent somatic and GI symptoms in veterans deployed to future military conflicts.

Keywords: Gulf War Illness (GWI), Heat Pain Threshold (HPTh), Cold Pressor Pain Threshold (CPTh), Ischemic Pain Threshold (IPTh), Ischemic Pain Tolerance (IPTo)

INTRODUCTION

Over 700,000 United States military personnel participated in the Persian Gulf War between August 1990 and March 1991. By April 1997, the Persian Gulf Registry had identified a large number of these veterans as having chronic health disorders of undetermined etiology. Within 6 to 12 months after their return, up to 25% of Veterans had persistent gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms possibly related to their military service in the Gulf.1–3 The economic impact of these chronic GI disorders (workup, treatment, indirect costs, lost work) is estimated to be over $897 million (VA Environmental Epidemiology Service). Costs continue to grow because a large number of veterans still serve in the Middle East and are at high risk for developing the same chronic disorders.

Among the symptoms most frequently reported by veterans with Gulf War Illness (GWI) were chronic fatigue, frequent or persistent headache, frequent or persistent muscle or joint pain, and GI symptoms. GI symptoms (e.g. diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain) reported by these veterans accounted for the majority of complaints.4–6 It is estimated that over 50% of veterans deployed in the Gulf during the Gulf war in 1990–1991 developed acute gastroenteritis.7 Thus, acute gastroenteritis may be an underlying factor leading Gulf War Veterans to develop GWI with persistent GI symptoms.8–9 Veterans deployed to the Persian Gulf are exposed to a highly stressful environment, making them more susceptible to the development of persistent GI symptoms.

Interestingly, it is the Gulf War Veterans with GI symptoms that also have the greatest number of somatic complaints. The acute GI symptoms following gastroenteritis resolve within a week, however, a significant number of Gulf War Veterans are left with chronic and persistent abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating.4 Transient small bowel and colonic inflammation due to enteric infections acquired by veterans in the Persian Gulf may cause sensitization of the gut and enteric neurons to nociceptive stimuli, which can persist long after resolution of the inflammation, similar to changes observed in animal models of functional GI disorders.10–12 Sensitization of enteric neurons may then lead to central sensitization and be manifested by evidence of somatic hypersensitivity to experimental nociceptive stimuli as we have shown in patients with IBS.11,13–15

The overall goal of the current study was to determine alterations of pain processing mechanisms reflected in somatic hypersensitivity to experimental nociceptive stimuli in veterans with GWI with and without chronic GI symptoms compared to healthy veteran controls. Thus, our overall hypothesis was to determine if veterans with GWI and chronic GI symptoms exhibit heightened patterns of somatic pain perception (hypersensitivity) across nociceptive stimuli modalities. Well-controlled sensory stimuli designed to separately evaluate central and peripheral mechanisms were used to evaluate pain threshold affective ratings of contact thermal, cold pressor, and ischemic stimuli to compare differences in somatic hypersensitivity between veterans with GWI with GI symptoms; veterans with GWI without GI symptoms; and veteran controls. In addition to assessing perceptual responses, we also attempted to determine if the VAS ratings of the abdominal pain positively correlated with perceptual responses to the experimental pain stimuli in the veterans with GWI and GI symptoms.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

The study was performed at The Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Cincinnati, Ohio and the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating centers. All subjects signed informed consent prior to the start of the study. We enrolled consecutive veterans that (i) were previously deployed to the Persian Gulf, (ii) were between the ages of 30–72 at the time of enrollment, and (iii) developed GWI with or without chronic GI symptoms. Controls consisted of deployed GW veterans who did not develop GWI or GI symptoms.

All veterans with GWI with GI symptoms previously had upper endoscopy/colonoscopy with biopsies that were normal; a normal lactulose breath test to exclude bacterial overgrowth; a negative serum tissue transglutaminase to exclude celiac sprue; and negative stool studies; and underwent a 7-day screening period during which their daily abdominal pain score was recorded on a Mechanical VAS (M-VAS) and a mean was calculated.16 Fibromyalgia (FM) was excluded in all participating veterans using the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for FM.17 The asymptomatic Gulf War Veterans (controls) that were recruited were free of any evidence of acute and/or chronic somatic/abdominal pain based on a complete history and a physical exam. Veterans with GWI and controls were screened for systemic conditions that could affect sensory responses. None of the veterans took serotonin antagonists, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, or analgesic medication for at least 1 month prior to the study. Subjects were instructed to refrain from the use of caffeine for 72 hours before their session.

All Gulf War Veterans completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).18–19 Depressive and anxiety disorders were exclusions if they were severe enough to interfere with the individual’s ability to participate in the study. Therefore, veterans who scored ≥30 on the BDI and/or ≥53 on the STAI were excluded. Such scores are approximately one standard deviation above the mean for general medical patients.

2.2 Experimental Pain Procedures

Each veteran participated in an experimental session lasting approximately 1.5 hours. The order of administration of the 3 pain stimuli was randomly determined for each veteran to prevent any systematic effect of stimulus order. The sensory testing session was done on days that the veterans were free from abdominal pain and/or any extraintestinal symptoms (i.e. migraine headaches, back, or joint pain. The experimenter delivering the nociceptive stimuli was blinded to the group (GWI with abdominal pain, GWI without abdominal pain, control) to which the veteran belonged.

2.3 Heat Pain Threshold (HPTh)

All thermal stimuli were delivered using a computer-controlled Medoc Thermal Sensory Analyzer (TSA-2001, Ramat Yishai, Israel), which is a peltier-element-based stimulator with a 3 × 3 cm thermode. Temperature levels were monitored by a contactor-contained thermistor, and returned to a preset baseline of 32°C by active cooling at a rate of 10°C/Sec. Heat pain thresholds were assessed on the ventral aspect of the right sole of the foot using an ascending method of limits. From a baseline of 32°C, probe temperature increased at a rate of 0.5°C/Sec until the subject responded by pressing a button on a handheld device. This slow rate of rise preferentially activates C-fibers and diminishes artifacts associated with reaction time.20 Veterans were instructed to press the button when the sensation “first becomes painful.” Three trials of HPTh were presented and the average of the 3 trials was calculated for heat pain threshold. The position of the thermode was altered proximal to the site but not overlapping between trials in order to avoid either sensitization or habituation of cutaneous receptors. In addition, interstimulus intervals of at least 5 minutes were maintained between successive stimuli.

2.4 Cold Pressor Pain Threshold (CPTh)

The cold-pressor procedure was conducted as previously described.21–22 Veterans immersed their right foot in 5°C water. The water temperature was maintained (+ 0.1°C) by a refrigeration unit (Neslab, Portsmouth, NH), and the water was constantly recirculated to maintain a constant temperature throughout the water bath and to prevent local warming around the submerged foot. Veterans were told that they could remove their foot at any time if the pain became intolerable. CPTh was determined when the veteran first felt pain. Three trials were done and the average of the 3 trials was computed for cold pain threshold. An interstimulus interval of at least 5 minutes was maintained between successive stimuli.

2.5 Ischemic Pain Threshold (IPTh) and Tolerance (IPTo)

The ischemic test was conducted using a modified submaximal effort tourniquet test.23 The right arm was exsanguinated by elevating it above heart level for 60 secs after which the right arm was occluded with a straight segmental blood pressure cuff inflated to 240 mm Hg using a Hokanson cuff inflator and air source (Bellevue, WA). Veterans were then instructed to do 20 hand grip exercises of 2-sec duration at 4-sec intervals at 50% of their maximum grip strength. Veterans were instructed to say “pain” when they first felt pain (IPTh) and to continue until the perceived pain became intolerable (IPTo) or for 15-min. Then, the trial was repeated for a total of 3 times with at least 5 minutes in-between testing, and the average time to IPTh and IPTo was recorded for each veteran.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done using SAS software, Version 9.4 of the SAS system (SAS institute Inc.) and Prism version 6. The analysis involved one between- and two within-subject variables, and, consequently, the repeated measures command within the General Linear model module of SPSS was also used. Differences between veterans with GWI and GI symptoms; veterans with GWI without GI symptoms; and asymptomatic veterans for HPTh, CPTh, and IPTh were tested. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s comparison was used to analyze the pain testing data. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Pearson correlations between M-VAS abdominal pain ratings in the GWI with GI symptoms and HPTh, CPTh, IPTh, and IPTo were analyzed.

3. RESULTS

Gulf War Veterans that had been deployed were recruited for this study from the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida and from the Cincinnati VAMC in Cincinnati, Ohio. A total of 138 veterans completed the study: 53 had documented GWI with chronic GI symptoms; 47 had GWI without GI symptoms; and 38 were asymptomatic and did not develop GWI or GI symptoms during deployment and were asymptomatic at the time of this study and served as controls. Clinical characteristics and demographics of the enrolled Gulf War Veterans were similar in the 3 groups (Table 1). Mean age was 47.9±3.0 years; 93% were male. There was no difference between the two groups in age, sex or ethnicity using a comparison analysis. There were no group differences on the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or between Gulf War Veterans who developed GWI and asymptomatic veterans (p=0.7). Covariate analysis was done but did not reveal any effects of group membership on scores on the STAI, or BDI. Some of the veterans with GWI and chronic GI symptoms included in the study had a history of extraintestinal symptoms, but they were all free from acute abdominal pain and/or extraintestinal symptoms during the day of sensory testing.

Table 1.

Demographics of Enrolled Gulf War Veterans

| GWI/GI Symptoms (N=53) | GWI (N=47) | Controls (N=38) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||

| Age--yr | 49.1±3.7 | 48.2±1.2 | 46.6±4.1 |

| Sex—no. (%) | |||

| Male | 48 (91) | 47 (100) | 34 (90) |

| Female | 5 (9) | 0 | 4 (10) |

| Ethnic group-no. (%) | |||

| White | 27 (51) | 39 (83) | 21 (55) |

| Black | 25 (47) | 8 (17) | 17 (45) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Plus-minus values are means±SD. There were no significant differences between the 3 groups. All Gulf War Veterans were deployed to the Persian Gulf.

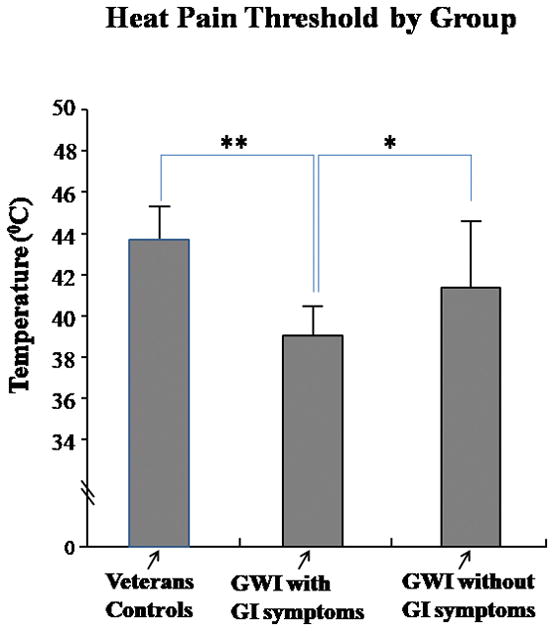

3.1 Heat Pain Threshold (HPTh)

Gulf War Veterans with GWI/GI symptoms exhibited lower HPTh in response to the thermal probe stimulation of the sole of the foot compared to veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms) (*p<0.01) and veteran controls (**p<0.001) (Figure 1). There was no significant difference between veteran controls and veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms). Comparison of tests of thermal stimulation of the foot yielded a significant main effect for group (p<0.001). This indicated that veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had significantly higher pain ratings compared to veterans with GWI and veteran controls.

Figure 1.

Heat Pain Threshold by Group: Gulf War Veterans with GWI/GI symptoms exhibited lower HPTh in response to the thermal probe stimulation of the sole of the foot compared to veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms); *p<0.01; **p<0.001

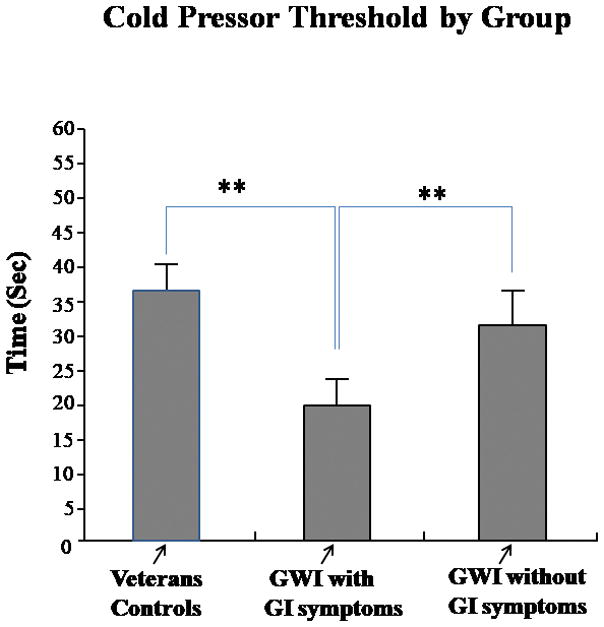

3.2 Cold Pressor Pain Threshold (CPTh)

In the cold pressor test, veterans with GWI/GI symptoms exhibited lower CPTh scores in response to cold water immersion of the foot compared to veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms) (*p<0.01) and veteran controls (**p<0.001) (Figure 2). There was no significant difference between control veterans and veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms). Comparison of cold water immersion of the foot yielded a significant main effect for group (p<0.001). The results indicated that on this test, too, veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had significantly higher pain ratings compared to veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms) and veteran controls.

Figure 2.

Cold Pressor Threshold by Group: Gulf War Veterans with GWI/GI symptoms exhibited lower CPTh in response to immersion of their right foot in 5°C water compared to veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms). *p<0.01; **p<0.001

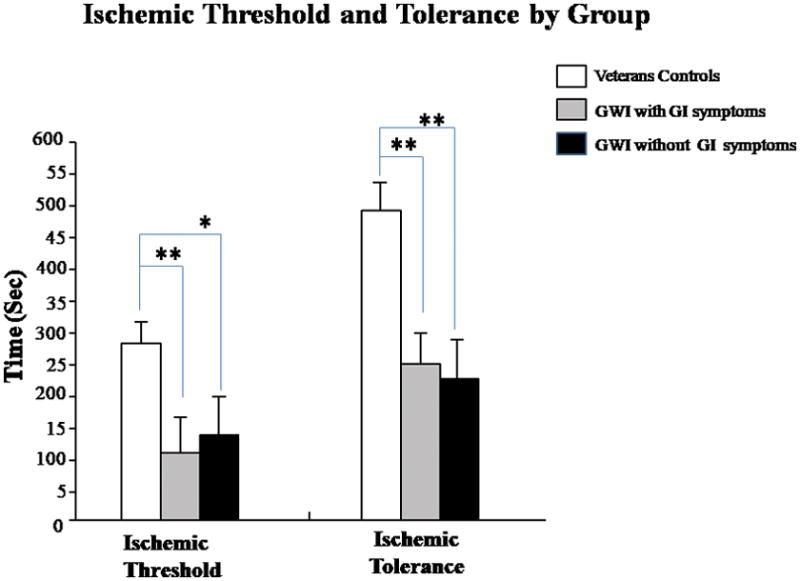

3.3 Ischemic Pain Threshold (IPTh) and Ischemic Pain Tolerance (IPTo)

On the modified tourniquet test, veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had a shorter time to IPTh (p<0.001) than veteran controls (Figure 3, Left Panel). Interestingly, veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms) also had a significantly shorter time to IPTh compared to veteran controls (p<0.01) (Figure 3, Left Panel). On the ischemic tolerance test (IPTo), veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had a lower tolerance (IPTo) compared to control veterans (p<0.001) (Figure 3, Right Panel). Similar to IPTh, veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms) also had a significantly shorter time to IPTo compared to veteran controls (p<0.01) (Figure 3, Right Panel).

Figure 3.

Ischemic Threshold and Tolerance by Group; Gulf War Veterans with GWI/GI symptoms exhibited lower IPTh and IPTo in response to immersion of their right foot in 5°C water compared to veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms); *p<0.01; **p<0.001

3.4 M-VAS Abdominal Pain Correlations

Pearson correlations between M-VAS abdominal pain ratings and the main outcome measures of heat pain threshold, cold pressor threshold, and ischemic pain threshold were analyzed (Table 2). Among veterans with GWI/GI symptoms, there were significant correlations between the M-VAS abdominal pain ratings and heat pain threshold, cold pressor threshold, and ischemic pain threshold and tolerance. Thus, veterans with greater average daily abdominal pain had greater somatic sensitivity to experimental nociceptive testing.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients for veterans with GWI and GI symptoms

| M-VAS Abdominal Pain Rating | ||

|---|---|---|

| Heat Pain Threshold (HPTh) | 0.694 | p<0.001 |

| Cold Pressor Threshold (CPTh) | 0.682 | p<0.001 |

| Ischemic Pain Threshold (IPTh) | 0.764 | p<0.001 |

| Ischemic Pain Tolerance (IPTo) | 0.792 | p<0.001 |

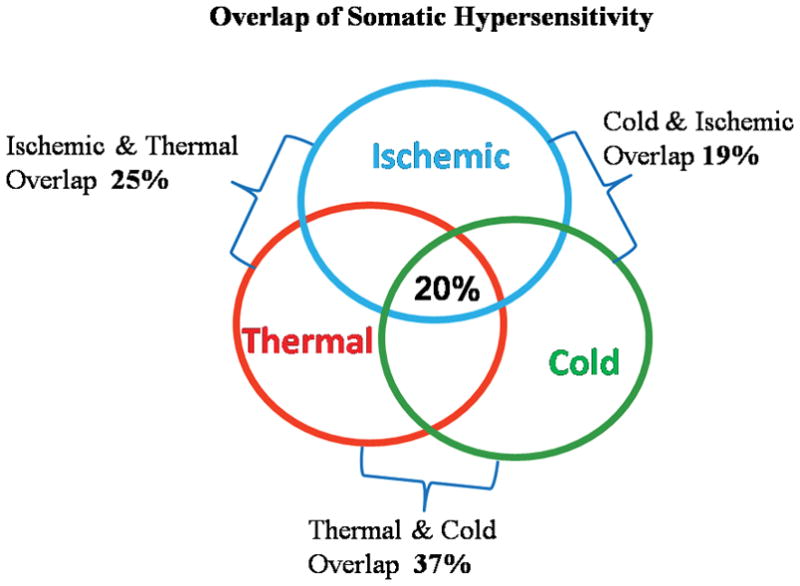

3.5 Overlap of Somatic Hypersensitivity in Gulf War Veterans

Figure 4 depicts the overlap among veterans with GWI/GI symptoms who had hypersensitivity to thermal, cold pressor, and ischemic nociceptive stimuli. A total of 20% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had hypersensitivity to all 3 nociceptive stimuli (thermal, cold, and ischemic). Overlap of both thermal and ischemic hypersensitivity were present in 25% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms. A total of 19% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had overlap of both cold and ischemic hypersensitivity. Finally, the largest overlap (37%) was between thermal and cold hypersensitivity in veterans. There were no differences in scores on the BDI and STAI between the groups of veterans with overlap. The 20% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms that had overlap with all 3 nociceptive stimuli also had a history of >85% of extraintestinal symptoms.

Figure 4.

Overlap of Somatic Hypersensitivity: depicts the overlap among veterans with GWI/GI symptoms who had hypersensitivity to thermal, cold pressor, and ischemic nociceptive stimuli. A total of 20% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had hypersensitivity to all 3 nociceptive stimuli (thermal, cold, and ischemic). Overlap of both thermal and ischemic hypersensitivity were present in 25% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms. A total of 19% of veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had overlap of both cold and ischemic hypersensitivity. Finally, the largest overlap (37%) was between thermal and cold hypersensitivity in veterans.

4. DISCUSSION

Here we have shown that the onset of chronic abdominal pain and GI symptoms in veterans with GWI is common during deployment and often persists after deployment. This study demonstrates several important new findings. Our present study compared differences in somatic hypersensitivity between veterans with GWI/GI symptoms and is unique in several ways. To our knowledge, this is the 1st study to examine somatic pain perception in veterans with GWI using a battery of diverse experimental pain procedures and well-validated psychophysical pain testing procedures. Second, our results show the presence of somatic hypersensitivity in veterans with GWI/GI symptoms suggesting an alteration in afferent pain processing mechanisms. This suggests that chronic peripheral nociceptive input from the gut may sensitize spinal cord neurons as we have previously shown in patients with functional bowel disorders such as IBS.11,13–15 Third, there was a significant overlap of thermal, ischemic, and cold pressor hypersensitivities among veterans with GWI/GI symptoms (Figure 4). This suggests that different mechanisms may play a role in the hypersensitivity seen with diverse nociceptive pain stimuli, as veterans with a history of the greatest number of extraintestinal symptoms had the highest overlap of hypersensitivities to nociceptive stimuli. Finally, there was a positive correlation of abdominal pain ratings and somatic hypersensitivity in veterans with GWI/GI symptoms on the experiment nociceptive pain tests. This correlation suggests the possibility of viscerosomatic convergence of central and peripheral pain processing pathways in veterans with GWI/GI symptoms.

These findings extend our studies of GWI. Our research team has been studying Gulf War Veterans with GWI and chronic GI pain disorders that started during their deployment to the Persian Gulf in 1990–91.4 The pathophysiologic mechanisms of GI symptoms are not well understood, but these mechanisms cause significant morbidity in Gulf War Veterans. Among the symptoms most frequently reported by veterans with GWI were chronic fatigue, frequent or persistent headache, frequent or persistent muscle or joint pain, and GI pain. Indeed, GI symptoms reported by these veterans accounted for the majority of complaints.3,5,24

The mechanisms underlying the GI symptoms are unclear. One of the earliest studies evaluated 57 deployed and 44 non-deployed members of a National Guard unit in an attempt to better define the etiology and prevalence of chronic GI symptoms in Persian Gulf War Veterans.6 After deployment to the Persian Gulf region, up to 80% reported chronic GI pain that persisted after their tour of duty. The abrupt onset of gastrointestinal pain was coincidental with deployment to a stressful wartime environment. Despite this high prevalence, the mechanisms of chronic gastrointestinal pain in Gulf War Veterans is not well understood.4,11 There have been several potential causes entertained including a post-infectious, IBS-like syndrome.25–27 The acute symptoms will usually resolve within a week although abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating often persist. Interestingly, transient bowel inflammation may cause sensitization of the gut that persists long after resolution of the inflammation, similar to the sensitization shown in animal models of gastrointestinal pain.10,28–34

Somatic symptoms may be important in GWI/GI symptoms as they exhibit a wide variety of somatic symptoms including back pain, migraine headaches, heartburn, dyspareunia, and muscle pain in body regions somatotopically distinct from the gut. Collectively, these somatic symptoms suggest that Gulf War Veterans with GWI/GI symptoms may also suffer from central hyperalgesic dysfunction similar to patients with IBS.14,21 Patients with other chronic pain disorders such as temporomandibular disorders have also been shown to have generalized hyperalgesia.35–36 Newer studies now suggest that processing of visceral and somatic stimuli overlap as a result of viscerosomatic convergence in the lumbosacral distribution.11 Chronic afferent nociceptive input from the gut may sensitize spinal cord neurons that exhibit somatotopic overlap with the gut. This spinal sensitization could be created and/or maintained by tonic impulse input from the gut to the spinal cord. We have previously shown that using a local anesthetic blockade in the colon (i.e. lidocaine jelly), both visceral and somatic hypersensitivity in IBS patients is diminished.17 Several recent studies by our group using an animal model of visceral and somatic hypersensitivity further supports the possibility of viscerosomatic convergence in these Gulf War Veterans with GWI and chronic GI symptoms.11 In this model, NMDA NR1 subunit expression was greater in the L4-S1 in laminae I & II of the spinal cord compared to the T10-L1 cord.32–34 Thus, our current findings for Gulf War Veterans confirm and extend our previous studies that suggest that a chronic visceral drive from the gut may be an underlying mechanism of somatic hypersensitivity in patients with other chronic pain conditions, such as IBS patients.

Our findings indicate that veterans with GWI/GI symptoms have greater thermal sensitivity than veterans with GWI and veteran controls as the former group reported a lower pain threshold to heat stimuli applied to the sole of the foot. These findings support our previous studies indicating that some IBS patients are more sensitive to heat stimuli than controls.14 The cold pressor task is a commonly used experimental pain task and cardiovascular challenge. Veterans with GWI/GI symptoms also showed significantly lower thresholds to the cold pressor stimuli applied to the foot compared to veterans with GWI and veteran controls. Finally, during the ischemic test, veterans with GWI/GI symptoms had a shorter time to pain threshold and pain tolerance. Interestingly, in comparison to the thermal and cold pressor tests, veterans with GWI (no GI symptoms) had a lower ischemic threshold and tolerance compared to veteran controls. These findings can be explained given the perceptual qualities of the ischemic test, the robust pain experienced may be more likely to reveal somatic hypersensitivity. The modified submaximal effort tourniquet procedure used in our current study produces a diffuse, deep pain that is associated with activation of a large number of C fibers in the muscle, compared to other nociceptive stimuli, which include primarily cutaneous stimuli of shorter duration and activate a greater proportion of a-delta fibers.23 Others have reported hypersensitivity when using this ischemic pain stimulus in temporomandibular disorders, fibromyalgia, and interstitial cystitis.37–38 It is interesting that there is a significant overlap in hypersensitivities among veterans with GWI/GI symptoms with thermal, cold pressor, and ischemic hypersensitivity. This suggests that different mechanisms may be at play in the hypersensitivities seen with diverse nociceptive pain stimuli, as the veterans with a history of the greatest number of extraintestinal symptoms had the greatest overlap of hypersensitivities to nociceptive stimuli.

There are a few limitations of our study. The study was conducted over 20 years after the war and there may be recall bias. Our study population mainly consisted of Gulf War Veterans enrolled in the Gulf War Registry at the Malcom Randall VAMC and at the Cincinnati VAMC. It is not clear whether these findings are applicable to veterans at other VAMCs. Also, veterans who agree to participate may be a biased sample that is more likely to report a higher prevalence of disorders. The higher prevalence of bowel disorders after the Gulf War may be due to increased health care utilization and higher reporting by the Veterans after returning from the War.

5. Summary

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that Gulf War veterans with GWI and persistent GI symptoms commonly have overlapping somatic hypersensitivity. The new findings in our study are important as they may lead to both novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for returning Gulf War Veterans who suffer from GWI/GI symtoms for which there are few available treatments. Gulf War Veterans with evidence of somatic hypersensitivity and GI symptoms may need more broad analgesic therapy rather than treatments just aimed at the gut. Moreover, evidence for the clinical relevance of experimental pain testing could lead to the development of more objective clinical markers of GWI and gastrointestinal symptoms that can be used in clinical trials.39–41 Somatic pain testing might be used to measure the changes in improvement following therapies given in clinical trials. These advances become even more important for an increasing number of veterans who are now serving in the Persian Gulf and are at a high risk of developing these chronic pain disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (CX000642-01A1 and CX001477-01) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK099052). The authors have no financial or other relationship to report that might lead to a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Baker DG, Mendenhall CL, Simbartl LA, Magan LK, Steinberg JL. Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported physical symptoms in Persian Gulf War veterans. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2076–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press; 2014. doi.org/10.17226/18623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA. 1998;280:981–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunphy RC, Bridgewater L, Price DD, Robinson ME, Zeilman CJ, 3rd, Verne GN. Visceral and cutaneous hypersensitivity in Persian Gulf war veterans with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Pain. 2003;102:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy FM, Kang HK, Dalager NA, Lee KY, Allen RE, Mather SH, Kizer KW. The health status of Gulf War veterans: lessons learned from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Registry. Mil Med. 1999;164(5):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sostek MB, Jackson S, Linevsky JK, Schimmel EM, Fincke BG. High prevalence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in a National Guard Unit of Persian Gulf veterans. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2494–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyams KC, Bourgeois AL, Merrell BR, et al. Diarrheal disease during Operation Desert Shield. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1423–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111143252006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Tribble DR. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:891–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez JL, Gelnett J, Petruccelli BP, Defraites RF, Taylor DN. Diarrheal disease incidence and morbidity among United States military personnel during short-term missions overseas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:299–304. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Q, Caudle RM, Price DD, Verne GN. Visceral and somatic hypersensitivity in a subset of rats following TNBS-Induced colitis. Pain. 2008;134(1–2):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Q, Verne GN. New insights into visceral hypersensitivity-clinical implications in IBS Patients. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:349–55. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Q, Yang L, Larson S, Basra S, Merwat S, Croce C, Verne GN. Decreased miR-199 augments visceral pain through translational up-regulation of TRPV1. Gut. 2016;65:797–805. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verne GN, Robinson ME, Vase L, Price DD. Reversal of visceral and cutaneous hyperalgesia by local rectal anesthesia in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients. Pain. 2003;105(1–2):223–230. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Q, Fillingim RB, Riley JL, Malarkey WB, Verne GN. Central and peripheral hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2010 Mar;148:454–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Price DD, Callam CS, Woodruff MA, Verne GN. Effects of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor on temporal summation of second pain (wind-up) in irritable bowel syndrome. J Pain. 2011;12:297–03. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, Harkins SW. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical raing scales. Pain. 1994 Feb;56:217–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geel SE. The fibromyalgia syndrome: musculoskeletal pathophysiology. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23(5):347–353. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberger CD, Gorusch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeomans DC, Proudfit HK. Nociceptive responses to high and low rates of noxious cutaneous heating are mediated by different nociceptors in the rat: electrophysiological evidence. Pain. 1996;68(1):141–150. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price DD, Craggs JG, Zhou Q, Verne GN, Perstein WM, Robinson ME. Widespread hyperalgesia in irritable bowel syndrome is dynamically maintained by tonic visceral impulse input and placebo/nocebo factors: Evidence from human psychophysics, animal models, and neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2009;47(3):995–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rainville P, Feine JS, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. A psychophysical comparison of sensory and affective responses to four modalities of experimental pain. Somatosens Mot Res. 1992;9(4):265–277. doi: 10.3109/08990229209144776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore PA, Duncan GH, Scott DS, Gregg JM, Ghina JN. The submaximal effort tourniquet test: its use in evaluating experimental and chronic pain. Pain. 1979;6:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(79)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(5):491–501. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwee KA, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Marshall JS, Walters SJ, Read NW. Psychometric scores and persistence of irritable bowel after infectious diarrhea. Lancet. 1996;347(8995):150–153. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKendrick MW, Read NW. Irritable bowel syndrome--post salmonella infection. J Infect. 1994;29(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(94)94871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mearin F, Perez-Oliveras M, Perello A, Vinyet J, Ibanez A, Coderch J, Perona M. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: one-year follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):98–104. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaloner A, Rao A, Al-Chaer ED, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Importance of neural mechanisms in colonic mucosal and muscular dysfunction in adult rats following neonatal colonic irritation. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2010;28:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Johnson AC, Cochrane S, Schulkin J, Myers DA. Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 receptor-mediated mechanisms inhibit colonic hypersensitivity in rats. Neurogastroenterology Motil. 2005;17:415–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Prusator DK, Johnson AC. Animal models of gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Animal models of visceral pain: pathophysiology, translational relevance, and challenges. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308(11):G885–903. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00463.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Q, Verne GN. NMDA receptor and colitis: basic science and clinical implications. Rev Analgesia. 2008;10(1):33–43. doi: 10.3727/154296108783994013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Q, Caudle RM, Price DD, Verne GN. Phosphorylation of NMDA NR1 subunits in the myenteric plexus during TNBS induced colitis. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406(3):250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Q, Caudle RM, Price DD, Verne GN. Selective up-regulation of NMDA-NR1 receptor expression in myenteric plexus after TNBS induced colitis in rats. Mol Pain. 2006;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Q, Price DD, Caudle RM, Verne GN. Spinal NMDA NR1 subunit expression following transient TNBS colitis. Brain Res. 2009;1279:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Kincaid S, Sigurdsson A, Harris MB. Pain sensitivity in patients with temporomandibular disorders: relationship to clinical and psychosocial factors. Clin J Pain. 1996;12(4):260–269. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarlani E, Greenspan JD. Evidence for generalized hyperalgesia in temoromandibular disorders patients. Pain. 2003;102(3):221–6. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carli G, Suman AL, Biasi G, Marcolongo R. Reactivity to superficial and deep stimuli in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2002;100(3):259–69. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00297-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fillingim RB, Loeser JD, Baron R, Edwards RR. Assessment of Chronic Pain: Domains, Methods, and Mechanisms. J Pain. 2016;17:T10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fillingim RB, Bruehl S, Dworkin RH, Dworkin SF, Loeser JD, Turk DC, Widerstrom-Noga E, Arnold L, Bennett R, Edwards RR, Freeman R, Gewandter J, Hertz S, Hochberg M, Krane E, Mantyh PW, Markman J, Neogi T, Ohrbach R, Paice JA, Porreca F, Rappaport BA, Smith SM, Smith TJ, Sullivan MD, Verne GN, Wasan AD, Wesselmann U. The ACTTION-American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy (AAPT): An evidence-based and multi-dimensional approach to classifying chronic pain conditions. J Pain. 2014;15:241–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Q, Wesselman U, Walker L, Lee L, Zeltzer L, Verne GN. AAPT diagnostic criteria for chronic abdominal, pelvic, and urogenital pain: Irritable bowel syndrome. J Pain. 2018 Mar 19;(3):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gewandter JS, Chaudari J, Iwan KB, Kitt R, As-Sanie S, Bachmann G, Clemens Q, Lai HH, Tu F, Verne GN, Vincent K, Wesselmann U, Zhou Q, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Smith SM. Research Design Characteristics of Published Pharmacologic Randomized Clinical Trials for Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Chronic Pelvic Pain Conditions: An Acttion Systemic Review. J Pain. 2018 Feb 2; doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.01.007. pii: S1526-5900(18)30055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]