Abstract

Background

Mothers with ovarian cancer are at risk for experiencing additional demands given their substantial symptom burden and accelerated disease progression.

Objective

This study describes the experience of mothers with ovarian cancer, elucidating the interaction between their roles as mothers and patients with cancer.

Interventions/Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of focus groups with women with advanced ovarian cancer. Using descriptive coding, we developed a coding framework based on emerging findings and group consensus. We then identified higher-order themes capturing the breadth of experiences described by mothers with ovarian cancer.

Results

Eight of the thirteen participants discussed motherhood. The mean age of participants was 48.38 (SD = 7.17). All women were White (9/9), most had some college education (6/9), and the majority were married (5/9). Mean time since diagnosis was 7.43 months (SD = 4.69); over half of women (5/9) were currently receiving treatment. Themes and exemplar quotes reflected participants’ evolving self-identities from healthy mother to cancer patient to woman mothering with cancer. Sub-themes related to how motherhood was impacted by symptoms, demands of treatment, and the need to gain acceptance of living with cancer.

Conclusions

The experience of motherhood impacts how women experience cancer and how they evolve as survivors. Similarly, cancer influences mothering.

Implications for Practice

Healthcare providers should understand and address the needs of mothers with ovarian cancer. This study adds to the limited literature in this area and offers insight into the unique needs faced by women mothering while facing advanced cancer.

Introduction

Women with ovarian cancer experience multiple ongoing cancer- and treatment-related symptom burden and additional threats to their quality of life. The most frequently reported symptoms in this population include fatigue, sleep disturbances, abdominal pain, and gastrointestinal concerns which are often difficult to manage and make day-to-day life challenging.1 Although the median age of diagnosis of ovarian cancer is 63 years,2 younger women are nonetheless frequently diagnosed. Women with a genetic predisposition to ovarian cancer (e.g., BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutations) are diagnosed at earlier ages and with more aggressive types of cancer than women without these vulnerabilities.3,4Research has demonstrated that younger women report higher levels of distress and lower quality of life than older women.2,3

One reason frequently posited for younger ovarian cancer survivors’ higher distress is their concurrent demands of family, career, and personal development.3 Women diagnosed in their 30s and 40s are frequently building their professional careers, starting families or raising young children, and managing the often-competing demands of these multiple roles. While these developmental stages likely impact women’s quality of life once diagnosed with cancer, no research to date has focused on how motherhood impacts ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences.

Estimates from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that over 1.58 million U.S. cancer survivors live with children under the age of 18.2 Yet the experiences of these patients remain largely unknown. The main objective of this study is to describe how ovarian cancer patients who are mothers perceive the impact of their cancer on their experience as a mother.

Materials and Methods

Parent Study

The parent study included four audio-recorded and transcribed focus group sessions of women with a history of ovarian cancer. Focus group participants (N=13) were recruited from a randomized clinical trial to improve symptom management among women with recurrent ovarian cancer [Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 259] and from the local chapter of the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition (NOCC). Eligibility criteria included adult (≥18 years old) females with a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Focus groups were held at a local café. The principal investigator of the parent study (TH) received training in qualitative analysis and focus group methodologies and led all focus groups with research assistants taking notes to document body language and the general tone of each group. Participants were asked questions about (1) how they manage their cancer- and treatment related symptoms, (2) how they define self-advocacy, and (3) how they self-advocate for their symptoms and in general. Participants were not explicitly asked about their experience as a mother, nor were specific questions asked regarding mothering. Additional details about the parent study are reported elsewhere.5

Qualitative Analysis

For the current study, we reviewed all four transcriptions and audio files from the parent study. We searched for the terms “mom”, “mother”, “kid”, “child(ren)”, “son”, and “daughter” in addition to reading the full transcripts for references to motherhood, parenting, and children. We extracted all discussions related to these topics. We used an adapted framework analysis to summarize and synthesize qualitative data into major themes and sub-themes for each question and for each participant. This iterative process began with a close read of all references to motherhood (coding) and successively summarizing the data to more abstract categories (sub-themes, themes, and overarching themes) that encompassed the codes.6 Specifically, the primary reviewer (JA) sent the five other reviewers excerpts from the first focus group to review and code using descriptive, axial coding. We included multiple reviewers to increase the trustworthiness and decrease any potential bias of our analysis. All six reviewers teleconferenced biweekly to discuss their coding and to develop an initial coding framework, including a codebook with detailed descriptions of each code. Using this coding framework, we then iteratively worked through the additional three transcripts, meeting regularly to discuss findings and revise the coding framework accordingly. We discussed any codes or excerpts for which there was disagreement until consensus was achieved. The primary reviewer maintained an audit trail documenting the rationales for any coding decisions that were made.

After the reviewers analyzed and coded the mothering-related excerpts from all four focus groups, each reviewer independently organized the final list of codes into higher-order groupings based on their close readings of the original transcripts and codes. All reviewers submitted their higher-order codes to the group, and a meeting was devoted to a collective discussion of how they had each developed their respective grouping schemas. The primary and senior authors (JA and TH) compared and contrasted these groupings before arriving at a final integrative coding schema which was shared with and confirmed by all reviewers. We used Microsoft Word and Excel for all coding procedures.

Results

Sample

The sample is described in Table 1. Nine of the thirteen women from the parent study independently mentioned being a mother during their focus group discussion and were included in this secondary analysis. Five of these women had been recruited from the GOG 259 research study; the remaining four women were recruited from the local NOCC chapter. Some women knew their sub-type of ovarian cancer-type (e.g., epithelial, germ cell, etc.), but most did not.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| M (SD) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 53.00 (13.48) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 5 (55.56%) | |

| Never married | 3 (33.33%) | |

| Divorced | 1 (11.11%) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 8 (88.89%) | |

| Black | 1 (11.11%) | |

| Education | ||

| High school | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Associated degree/some college | 5 (55.56%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 (11.11%) | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 1 (11.11%) | |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$25,000 | 1 (11.11%) | |

| $25–39,000 | 3 (33.33%) | |

| $40–84,000 | 2 (22.22%) | |

| >$85,000 | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Current employment status | ||

| Working full- or part-time | 3 (33.33%) | |

| Retired, not working | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Full-time homemaker | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Disabled | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Cancer characteristics | ||

| Years since diagnosis | 6.11 (4.28) | |

| Number of cancer recurrences | 0.89 (1.17) | |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||

| Stage I | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Stage II | 1 (11.11%) | |

| Stage III | 4 (44.44%) | |

| Stage IV | 1 (11.11%) | |

| Currently receiving treatment | ||

| Yes | 5 (55.56%) | |

| No | 3 (33.33%) |

Participants reported a mean age of 53.00 years (SD = 13.48). All women in this sample were White (9/9, 100.00%), and most had earned at least an associate’s degree or completed some college (7/9, 77.78%). More than half of women were married (5/9, 55.56%). The mean time since diagnosis was 6.11 months (SD = 4.28) and just over half (5/9, 55.56%) of the women were currently receiving treatment.

Coding Framework

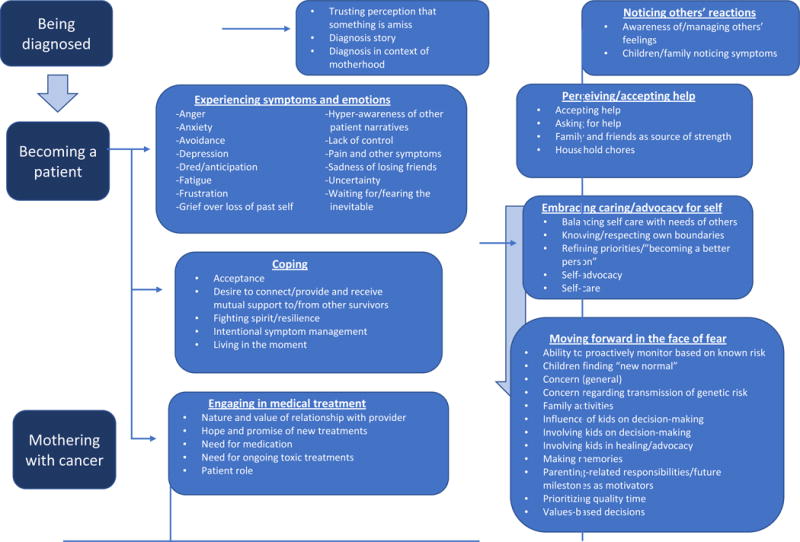

Our coding framework resulted in a central theme that encapsulated all higher-order themes and their respective individual codes. Importantly, our analysis was descriptive in nature and did not aim to identify a process. However, the qualitative data reflected a transformative, evolutionary process that, while not necessarily linear or unidirectional, was nonetheless described by the majority of mothers. The overarching theme described by the women in this study was that of role transformation. Women described this transformative process as one in which they took on specific role, first of being someone receiving the diagnosis of ovarian cancer, then taking the identity of a patient with cancer, and finally as someone who is simultaneously and inextricably a mother and a patient with cancer. Within each of these roles, common themes and sub-themes emerged as the women described their experiences managing their cancer while mothering. These are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Role transformation with themes and sub-themes

Findings

Figure 1 illustrates the overall relationship between the overarching theme of transformation, the three roles the women described within this transformation, and the themes, and sub-themes associated with each role. These classifications are not mutually exclusive, nor is movement among them linear. In reality, there is considerable overlap between the sub-themes. Table 2 also presents an overview of the three primary roles and their associated themes in addition to providing selected exemplar quotations for several of the sub-themes.

Table 2.

Role, Themes, Sub-themes, and Exemplar Quotations from Focus Groups with Mothers

| Role | Theme/Subthemes | Selected Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Being diagnosed | Trusting perception that something is amiss | “One day, my defining moment (which probably all of you had), was standing looking in the mirror at Kohl’s, I was shopping with my daughter and she’s in the next dressing room and I said I’m not buying any more clothes, this is ridiculous I look like I’m pregnant all the time and I pushed on my stomach and I thought this doesn’t feel like fat anymore and it was just looking in that mirror at that one moment…you know…okay now I’ve got to get to the bottom of this, something is wrong.” (Ma-FG2) |

| Diagnosis story | “I really didn’t have any symptoms before I was diagnosed either. I’d just moved to Virginia like six to eight months before. I had a newborn. I stopped nursing two weeks before I was diagnosed. I had a kid that just started kindergarten. I was just getting used to it, I was tired but I had three little kids five and under. And, um, I noticed that my belly was getting a little bit bigger. I didn’t have any discharge. I didn’t have any back pain. I didn’t have any bloating. I didn’t have any of that stuff. And um, one day I just did a little twist thing and I could feel something swish.” (Sa-FG3) | |

| Diagnosis in context of motherhood | “Now when I was first diagnosed my daughter was only you know, a year old you know and I vowed to myself, “Oh my goodness I just had this little girl” I’m not going to just lose it all now, you know what I mean?” (Sa-FG3) | |

| Becoming a patient | Experiencing symptoms/emotions | “Nausea can get to you. They have awesome drugs, awesome drugs that help with that. But that was annoying. I never got sick-sick, I just didn’t feel good sometimes. And the kids were at home, so I was motivated to get off the couch and not lay around.” [Sub-theme: Nausea] (Sr-FG4) “…I mean I can’t even get up and get my kids dressed, I’m so tired.” [Sub-theme: Fatigue] (Sa-FG3) “…I mean just this depression you know you kind of have the wheels are always spinning in different scenarios but now you’ve got like death and who will pay the mortgage so the kids can live in the house, you know or how does this even work, you know…Sometimes I take a sleeping pill and just go to bed because I don’t even want to think about it anymore.” [Sub-theme: Concern (general)] (Ti-FG2) |

| Coping | “I can tell you right now any time that I find out that anybody has cancer I’m like give me their number, I’m calling them. I mean even if it’s just an acquaintance you know what I mean?” [Sub-theme: Desire to connect and provide or receive mutual support from other survivors] (Ta-FG1) “I’m just, you know, I’ll fight, I’ll fight tooth and nail… suck it up and don’t lay down…. pull your boots up higher and get through the muck, you know what I mean?” [Sub-theme: Fighting spirit/resilience] (Ta-FG1) “You know you just don’t go quietly and you fight for all you’re worth.” [Sub-theme: Fighting spirit/resilience] (Ta-FG1) |

|

| Engaging in medical treatment | “They listen to you and they care about you and these are people that you’re going to see over and over and over again. And they become family, I mean they really do.” [Sub-theme: Nature and value of relationship with providers] (Sr-FG4) | |

| Mothering with Cancer | Noticing others’ reactions | “Them watching me go through it? Uhhh, awful. Watching my 80-year-old parents take me to chemo, and having to deal with their baby being sick. And just knowing what she has and how bad it can be. I think that is hard. Very hard. I think it is hard to watch. Kids seeing their mummy. It’s tough.” [Sub-theme: Children/family noticing symptoms] (Sr-FG4) |

| Perceiving/accepting help | “Yes, but you know what? It’s really cool. I’ve got really incredible neighbors okay? And they had formed my own team.” [Sub-theme: Support from family and friends] (Sa-FG3) “Yeah. My parents had to get my little girl for that weekend. Like I would have chemo on Tuesday and then it would start maybe like Thursday night.” [Sub-theme: Mothering role affected by symptoms] (Ta-FG1) “Or find that little thing that’s going to make you strong. My daughter makes me strong. My parents make me strong…” [Sub-theme: Family and friends as source of strength] (Ta-FG1) |

|

| Embracing caring/advocacy for self | “It could be there’s a way to advocate for yourself when you’re dealing with the doctors and the hospitals and the professionals (and the bill collectors). But then there’s another kind of self-advocacy when you just say to your best friend’s 21-year-old daughter, no I will not all night babysit for you. Ain’t gonna happen! (Laughter) You know? “ [Sub-themes: self-advocacy, knowing/respecting own boundaries] (Ti-FG2) “But like the last time whenever I was on the couch it was like there were no ands, ifs, or buts about it…there was nothing I could do. (Almost apologetically) So I mean I just gave in and you know laid on the couch.” [Sub-theme: Resignation/giving in to symptoms for self-preservation] (Ta-FG1) “Well, yeah. Anyways, but I uh, I think I try to… I’ve become a better person. I try to deal with others better. I um, and you know any health issues, yeah I get up right up there right away whether it’s you know a pain in my back or you know something with my eyes or whatever, you just…okay here’s what we’re going to do, here’s what we’re not going to do, and that’s just it.” [Sub-themes: Self-care, self-advocacy] (Fr-FG3) |

|

| Moving forward in the face of fear | “The only thing quite honestly when it comes to this stuff is, I think about how much time it’s going to buy me. If it’s not going to buy me a lot of time or if it’s going to be something where I’m going to wind up being in the hospital, because with this last surgery I wound up getting infected and it just turned into a long hospital stay. Um, and it’s my kids, I mean that’s just it, I guess quality time with my kids. If I’m just going to be in the hospital and I’m going to be in and I’m just going to be laying there doing nothing, there’s no sense in me doing it.” [Sub-theme: Prioritizing quality time] (Sa-FG3) “And you know I’ve always got to be strong for my daughter. She really helps me live uh, just you know, making my days…you know what I mean…making me go for that extra day.” [Sub-theme: Parenting-related responsibilities and future milestones as motivators] (Ta-FG1) “And you know she makes me really strong. In fact, she made her first holy communion and I balled my eyes out…This is white dress number one and I’m going for white dress number two!” [Sub-theme: Making memories, Parenting-related responsibilities and future milestones as motivators] (Ta-FG1) “Every birthday, every Christmas, you know every time that one of my kids wakes up with a fever and I’m up with them at night and I’m the one that’s there holding the bucket for them when they’re throwing up. Every little thing like that is like a victory to me. It is odd, but it is my victory because I’m here.” [Sub-themes: Parenting-related responsibilities and future milestones as motivators] (Sa-FG3) |

The first role, or identity, is that of “being diagnosed with cancer.” Women described their memories of being on the precipice of a major life-changing event in which their former, relatively healthy self becomes a self that is ill with cancer as they described the symptoms and experiences leading up to seeking medical care and receiving a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. This role comprised the themes of a woman (a) trusting her perception that something was amiss in her body, (b) telling the story of how she received the diagnosis, and (c) framing the diagnosis in the context of her motherhood. Women described the physical symptoms that led to their diagnoses, some of which were subtle and non-specific, requiring the women to trust their own perceptions that something was amiss and to pursue evaluations to determine the underlying cause. Several women offered examples of how receiving the diagnosis affected them, particularly in the context of being a mother. One participant (Sa-FG3), speaking of attributing her fatigue to the fact that she had a young baby before realizing that it was related to a serious illness, said, “I had a newborn. I stopped nursing two weeks before I was diagnosed. I had a kid that just started kindergarten. I was just getting used to it, I was tired but I had three little kids five and under.” Another woman spoke of having a school-age daughter at the time she was diagnosed and described this relationship as a powerful incentive to maximize both the quantity and quality of time she could spend with her child.

The second role encompasses the experience of “becoming a cancer patient” and includes the three themes of (a) experiencing symptoms and emotions, (b) coping, and (c) engaging in medical treatment. Within each of these three themes are multiple sub-themes. Women spoke of the challenges presented by a multitude of symptoms and side-effects related to their disease and treatment. Physical symptoms including fatigue, nausea, and pain were frequently described as severe and distressing for women, often limiting their ability to engage in family activities and childcare duties. One woman (Sa-FG3) described the severe limitations due to her fatigue, “…I mean I can’t even get up and get my kids dressed, I’m so tired.” Emotional reactions including anger, anxiety, depression, dread, and grief were described as distressing reactions to the overwhelming stress these women felt. The demands of managing the symptoms and emotions of their cancer treatment required women to shift their focus onto their own needs in a way that was often at odds with the demands of motherhood as they had experienced it before becoming ill. They discussed ways they sought to cope with these challenges such as accepting the impact of the illness, seeking support from others, growing a fighting spirit, and living in the moment. For example, on woman (Ta-FG1) described her fighting spirit by saying, “You know you just don’t go quietly and you fight for all you’re worth.” Women also discussed their role as a cancer patient including engagement in medical treatment. They valued their relationships with their health care providers, some of whom became “like family” during their repeated encounters during the course of treatment. They reported recognizing the need for ongoing toxic treatments as a patient with cancer, but maintained hope that new treatments could help them in the future.

The third role identified is that of integrating experience of mothering with the experience of being a cancer patient to become a woman “mothering with cancer.” This role comprises the four themes of (a) noticing others’ reactions, (b) perceiving/accepting help, (c) embracing caring/advocacy for self, and (d) moving forward in the face of fear. Each of the four themes contained numerous sub-themes, including women’s awareness of and need to manage the reactions of others, their struggles with asking for and accepting help, their reliance on family members and friends as sources of strength as well as tangible support and their growing ability for self-care and self-advocacy. As women embraced the identity of striving to balance the competing demands of motherhood and being a cancer patient, they spoke of numerous modifications and adaptations, such as relying on extended family and friends in new ways. Several women described developing new skills in respecting their own boundaries and their needs for self-care as well as changing their expectations of themselves and growing more comfortable relying on others for help and support. For example, one woman (Ti-FG2) described recognizing and asserting her own boundaries when she said, “But then there’s another kind of self-advocacy when you just say to your best friend’s 21-year-old daughter, ‘No, I will not all-night babysit for you. Ain’t gonna happen!’” Women described shifting their focus to making memories and savoring the present time with their children and families, and learning to move forward even as they contended with uncertain futures for themselves and their children. Several women mentioned that their children’s milestones (e.g., graduations, weddings, etc.) served as motivators for them to stay healthy and fight the cancer: “[My daughter] made her first holy communion and I balled my eyes out….This is white dress number one and I’m going for white dress number two!” (Ta-FG1). Children, and the women’s sense of attachment to and responsibility for them, were often cited as catalysts for change, serving as, in the words of one participant (Ta-FG1), “that one little thing that’s going to make you strong.” Even though women were aware of their ongoing risks and potential to pass genetic risks to their children, their decisions about how to live their lives centered around their ability to be an active, loving mother to their children in the present, while preparing their children to face whatever the future might hold.

Discussion

The experiences shared by mothers in the focus groups from which this study derived characterized their experiences with ovarian cancer. Although we did not set out to develop a model or even to identify a process, the experiences described by these nine mothers were those of evolution and transformation through the process of receiving a diagnosis, becoming a patient, and ultimately learning to balance the often-competing demands of mothering with those of being a patient with cancer.

Our results demonstrate that women negotiated mothering in the context of considerable demands on their time and energy. These demands came from multiple sources including managing their physical and emotional symptoms, needing to find coping mechanisms, working with their health care teams, and figuring out how to have an active role in their treatment plans. Nonetheless, women managed to mother even in this challenging context. While these challenges may have added stress and burden to their lives, their stories indicated that their roles as mothers propelled them forward, orienting them toward the future and providing them with strength and motivation to creatively navigate the challenges of their illness and achieve a sense of normalcy for themselves and their families.

Our analysis confirms research documenting high rates of psychological distress in mothers with cancer. Ernst,3 Park,7 Ares,8 and colleagues have documented that patients with advanced cancer living with dependent children not only have higher rates of distress compared to patients without dependent children, but also that these patients prefer more aggressive treatment and were less likely to engage in advance care planning. Similar to our analysis in which women altered their decision-making to focus on providing for their children, mothers may avoid end-of-life planning and/or supportive oncology services with the goal of aggressively treating their cancer and ensuring they can continue their mothering role.

This study echoes the findings of the small number of existing studies focused on understanding mothers with chronic or life-limiting illness. Wilson,9 for example, analyzed an empirical study of mothers living with HIV and found a similar theme of disease causing role disruption and reconfiguration of self-identity. Similarly, Fisher10 noted how mothers with breast cancer reconstructed their identities to maintain a sense of normalcy and continue their mothering role in the context of cancer. Davey11 and colleagues qualitatively explored the experience of women with breast cancer caring for their children and found similar dialectics between wanting to manage their children’s experience of their cancer, protecting them from the physical and emotional problems, while also wanting to foster open, safe communication and realistic expectations about the realities of the cancer.

There are limitations to this qualitative study. Since the parent study was focused on self-advocacy rather than motherhood, we did not specifically request information about being a mother on our socio-demographic form, and therefore we do not know if other women from the parent study may have been mothers as well. For the same reason, we do not have demographic information regarding the number or ages of children that each of the women had. However, the women included in this secondary analysis all spontaneously discussed being mothers during their participation in the focus groups, suggesting that mothering was a significant and important role in their lives and in their cancer journeys, and strengthening the results of this analysis. Given the small sample of this qualitative study, future research should include a larger, more diverse sample of patients with ovarian cancer.

Conclusions

This study provides descriptive insight into the understudied area of mothering with ovarian cancer. The words of the mothers in this study described a transformational experience from being diagnosed with cancer to becoming a cancer patient to negotiating mothering in the face of cancer, and they illuminate the demands of being a mother while facing the challenges of managing a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. While these mothers sought to provide for and nurture their children while managing their own illness, they also spoke of the need to continuously reprioritize and renegotiate competing demands. Future research should consider how motherhood impact the decision-making, symptom management, and supportive care needs and priorities of mothers with cancer.

Implications for Practice.

Additional research is needed to further elucidate the experience of mothers with cancer so that tailored interventions can be developed to meet the specific needs of this population in a manner that supports their optimal quality of life and goals of care through healthy integration of the roles of cancer patient and mother. These findings provide insight into the transforming roles from healthy mother to cancer patient to woman mothering with cancer experienced by mothers with ovarian cancer. This knowledge informs practitioners’ interactions with women facing the unique challenges of being a mother and being a cancer patient. In order to more fully address the needs of mothers facing ovarian cancer, clinicians should consider mothers’ priorities of providing and caring for their children and families and their goal-setting, treatment-planning, and supportive care discussions with patients should explore and acknowledge these important motivations.

Acknowledgments

Funding: (JA and TH) T32 NR011972 National Institute of Nursing Research (PI: Bender)

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Janet A. Arida, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Toby Bressler, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, New York.

Samantha Moran, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Sara D’Arpino, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Alaina Carr, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado.

Teresa L. Hagan, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Price MA, Bell ML, Sommeijer DW, et al. Physical symptoms, coping styles and quality of life in recurrent ovarian cancer: a prospective population-based study over the last year of life. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Alfano CM, McNeel TS. Parental cancer and the family: a population-based estimate of the number of US cancer survivors residing with their minor children. Cancer. 2010;116(18):4395–4401. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernst J, Götze H, Krauel K, et al. Psychological distress in cancer patients with underage children: gender-specific differences. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):823–828. doi: 10.1002/pon.3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mays D, DeMarco TA, Luta G, et al. Distress and the parenting dynamic among BRCA1/2 tested mothers and their partners. Health Psychol. 2014;33(8):765–773. doi: 10.1037/a0033418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagan TL, Donovan HS. Ovarian Cancer Survivors’ Experiences of Self-Advocacy: A Focus Group Study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(2):140–147. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.A12-A19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale N, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(11) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020748910002063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park EM, Deal AM, Check DK, et al. Parenting concerns, quality of life, and psychological distress in patients with advanced cancer. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arès I, Lebel S, Bielajew C. The impact of motherhood on perceived stress, illness intrusiveness and fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors over time. Psychol Health. 2014;29(6):651–670. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.881998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson S. “When you have children, you”re obliged to live’: motherhood, chronic illness and biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(4):610–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher C, O’Connor M. “Motherhood” in the context of living with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(2):157–163. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821cadde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davey MP, Nino A, Kissil K, Ingram M. African American Parents’ Experiences Navigating Breast Cancer While Caring for Their Children. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1260–1270. doi: 10.1177/1049732312449211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]