Main Text

Despite the fact that the idea of personalized medicine in cancer has been accentuated in the last years of research, this concept is well rooted in the history of medicine: “It is more important to know what sort of person has a disease than to know what sort of disease a person has” (Hippocrates 450–370 BCE). We understood that the right therapy has to be administrated in the right amount, to the right patient, under the right conditions, and finally at the right time. But what if the safe amount is not necessarily the most effective one? In light of these aspects, researchers have developed combinatorial strategies of anti-cancer drugs to avoid a heavy insult in terms of toxicity and also installation of drug resistance. The question that arises at this moment is: how do we deal with the last generation forms of therapy in the name of microRNA (miRNA) modulation?

miRNAs are short non-coding sequences that impair the expression of specific genes mainly by targeting the complementary transcript. The panel of targeted transcripts is now made available through a wide selection of databases that comprise the experimental validation of the interactions and also the predicted ones (e.g. miRWalk1). Although this vast network of regulation is responsible for the normal function of numerous pathways inside the cell, the aberrant expression of miRNAs is becoming a central part in cancer initiation and development. We are currently aware that these small transcripts are involved in every cancer hallmark mainly through downregulated profiles for the tumor suppressor miRNAs and exacerbated expression for the oncogenic ones. These aspects were discussed over and over in the last years in the scientific literature and numerous proposals with miRNAs as therapeutic agents were published in the oncological domain.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 However, considering the complex scheme behind miRNA signaling, where the targeting takes place in a multicoordinated system—one miRNA can target multiple transcripts and one transcript can be targeted by more than one miRNA—the following statement becomes plausible: one single miRNA sequence, despite the extended role throughout entire signaling pathways, is not able to hazardously disrupt the development of cancer cells and completely eradicate the pathology within the organism in safe administrated doses. This affirmation comes from the idea that a tumor suppressor gene could be experimentally enforced through downregulation of an oncogenic complementary miRNA, but this is not necessarily a secure strategy considering that there are other miRNAs that can still target the same transcript. Still, the same miRNA can simultaneously target tumor suppressor and oncogenic genes in context-dependent situations, weakening the treatment efficiency or, even worse, producing long-term side effects. Moreover, the ability of cancer cells to develop compensatory mechanism by activating bypassing systems is also affecting the possibility of using miRNAs as single agents in preclinical and/or clinical therapeutics. The first clinical trial involving the experimental upregulation of miR-34 has underlined important safety aspects regarding this type of therapeutic approach and urged the need for other perspectives.

To obtain a superior yield in terms of cancer therapy, we are proposing a novel kind of approach where miRNA modulation could be used as the first line of treatment to disrupt the cancer cell at multiple levels, followed by administration of small molecule inhibitors for specific cancer-driven targets in the attempt to obtain a superior effect at lower doses. This approach has a molecular level of action for both therapeutic molecules, where the suppression of a specific target by a small molecule inhibitor could be sustained by a synergistic miRNA concentrated on the same oncogenic pathway. Moreover, the ability of miRNAs to modulate multiple transcripts from the same or interconnected molecular mechanisms (e.g. apoptosis, epithelial to mesenchymal transition [EMT], angiogenesis, etc.) represents a steady advantage,8, 9, 10 where the effect of miRNA will be perceived at a more general level and the small molecule will strongly attack the principal knot from the altered oncogenic pathway (the principal knot is considered a molecule that is strongly overexpressed and functional within a oncogenic pathway; the principal knot can also be cancer specific). In this way, the tendency of cancer cells to overcome the impairing effects through activation of adaptive loops will be hampered by a well-chosen non-coding sequence able to modulate targets that could be used by malignant cells for activation of secondary paths. Importantly, the chosen signaling knot (referred to as the main targeted oncogenic molecule) will be inhibited by both agents to obtain a maximum impairing effect with smaller doses. In this way, the potential toxicity and implicit side effects will be strongly diminished, preserving or even improving the malignant inhibitory effect. In general terms, the exogenous miRNA is used for weakening of cancer cell due to its ability to target multiple transcripts, where the second line of treatment is used as a powerful targeted agent able to eradicate the cancer cell through different mechanisms (e.g. apoptosis, inhibition of cell cycle, necrosis, etc). The effect of the second therapeutic will be significantly improved due to the already weak malignant phenotype obtained after the restoration of a specific miRNA expression. This approach represents a novel perspective upon miRNA therapeutics, where the non-coding sequence is not the central part of the treatment scheme, but is contributing to the efficiency of the second type of therapy. Despite the fact that the proposed molecule for the second administration consists in a specific small molecule inhibitor, there is the possibility to replace this one with other types of therapies, even with the classical chemotherapy.

Another Perspective on miRNA Therapeutics

One of the marked points in molecular oncology consists of the implementation of non-coding RNA sequences, partially represented by miRNAs, as important influencers of cancer-related pathways.3

Despite numerous research conducted on this type of therapy,11, 12, 13 there are still major concerns related to the actual clinical effects of miRNA modulation. As is the case of any other drug, there is the need for numerous optimization protocols in order to reduce the unwanted effects and potentiate the beneficial one. Several issues related to delivery platforms—optimal dosage, unwanted toxicity, and achieving targeted administration—are still the subjects of intense studies.14, 15 One particular situation that is quite specific for non-coding oligonucleotides-based therapies is that, compared to the usual situation, where one main target is affected, miRNAs influence numerous elements within the cell, and the assessment of the specific downstream effect becomes much more difficult to evaluate. In the moment of increased administration, when the dose is being pushed to the highest levels to obtain a clear effect, the risk of unwanted targeting is clearly potentiated. This type of toxicity is primarily divided into two categories: hybridization dependent and hybridization independent (or chemistry-related effects). For the first category, it is possible to force the modulation of the targeted genes by administering excess therapeutic compound (exaggerated pharmacology) or to determine off-target effects caused by unspecific binding. For the last case, there is also the possibility of saturation concept, when the exogenous sequence is administrated in doses that exceed the amount of target sequences present in the malignant cell and, in this way, the probability of off-target effects is majorly increased. The second primary category, chemistry-related effects, generally refers to the structure of the miRNA sequence and the biological effects that are unrelated to the hybridization action. Importantly, like any other DNA- or RNA-based regimens, miRNA therapeutics can induce an innate immune response that will trigger an entire cascade of pro-inflammatory events. Nevertheless, another important aspect—secondary related to toxicology—consists of the gradual aspects of the therapeutic efficiency, where miRNAs act on primary targets that, in their turn, modulate downstream effectors. Considering that the sum of the pharmacological effects over time is able to cause a change in the disease phenotype establishes the pharmacological activity of a compound, it is highly possible that the immediate effect observed after miRNA exogenous expression or inhibition is not completely underlying the overall preclinical or clinical changes. This is actually a crucial issue in managing the dose of administrated miRNA compound, where a specific amount of inhibitor or mimic can cause a certain effect at the present time, an effect that can be potentiated afterwards, revealing supplementary toxicity.11, 16

In light of these aspects, it is crucially important to manage the doses of administrated miRNA therapeutics at highly specific levels and not lose sight of the potential side effects in favor of the beneficial and prominent ones.

The Opening toward a New Kind of Cancer Management

The switch from chemotherapy to molecular targeted agents has been implemented already in the oncological field with several successful cases: anti-estrogens and anti-androgens for the curative management of hormone driven breast and prostate cancer, all trans retinoic acid for acute promyelocytic leukemia patients that present translocation in the RARα retinoic acid receptor gene, and imatinib for ABL inhibition.17, 18, 19 The efficiency of these small molecule inhibitors determined the screening for other potential therapeutics with similar mechanisms of action but concentrated on additional altered molecules within the targeted pathology. It is now clear that we understand the importance of stratified medicine, and this concept is generously gaining its value within the clinical scenarios. The switch from the classical standard of care comprising cytotoxic chemotherapy to targeted agents (monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors) in cancer treatment has revolutionized the outcome for several types of oncological patients: imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia and trastuzumab, rituximab and sunitinib in the context of breast malignancies, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and renal cell carcinoma. By affecting specific effectors that contribute to the sustenance of cancer cells, in comparison with the general citotoxicity on dividing cells of the chemotherapeutic regimens, targeted agents have managed to improve the survival statistics and also offer supplementary options for patients with medical comorbidities due to less toxicity and improved tolerability.20, 21, 22 However, there are also some limitations that need to be overcome in order to make the most of this concept.

One such issue pertains to the genetic heterogeneity of cancer cells, including the intra-tumor variations, where the genotype of a cancer cell is not necessarily identical to the genotype and implicit phenotype of another cell within the same malignant mass.23, 24, 25 In this way, such cells could respond in a different manner to the activity of the small molecule inhibitor where, in one particular case, the inhibitory agent is efficient and, in the other case, the effect is diminished or impaired.

Another major issue is drug resistance, where the cell can become insensitive to the action of the small molecule inhibitor through activation of feedback loops26 or alternative signaling pathways.27, 28 Also, there is the possibility of mutation acquisition within the target itself and implicit incompatibility between the small molecule inhibitor and modified targets.29

There are also additional issues related to this type of strategy in cancer treatment, such as the discovery of potent malignant driven targets that, once inhibited, will determine a prominent effect; synthesis of efficient agents; and also time-consuming phases between basic research and clinical implementation.

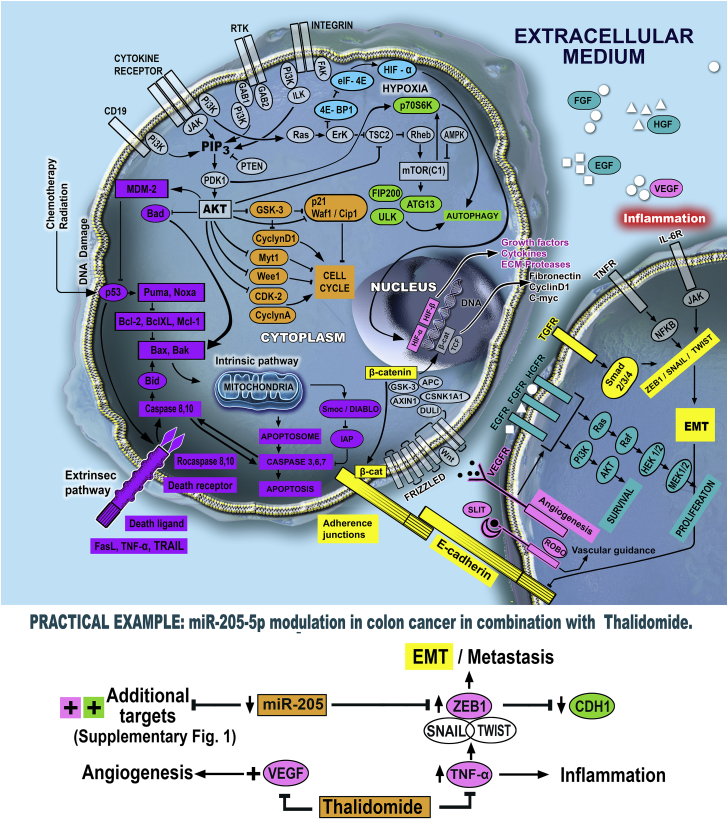

In light of the discussed aspects, we are proposing a novel type of combined therapy by merging the effects of miRNA inhibition or replacement with the action of small molecule inhibitors to obtain a superior inhibitory effect upon cancer cells. Figure 1 presents possible therapeutic options for different pro-carcinogenic signaling networks within cancer cells, based on combinatorial strategies between miRNAs and small molecules.

Figure 1.

The Main Pathways Involved in Cancer Development and Potential Therapeutic Combinations Targeted toward Them

The survival, proliferation, and invasion of malignant cells are sustained by specific interconnected mechanisms, where central genes are losing their normal function and/or expression and contribute to the development of cancer. To control this aberrant signaling, there is the possibility to use miRNAs in combination with small molecule inhibitors to restrict the pathological function of a central gene through a multi-targeted approach. Moreover, due to the multiple targets corresponding to a specific miRNA sequence, it is also possible to target more than one mechanism, disrupting the cancer cells at multiple levels.

The proposed idea consists of administration of miRNA inhibitors or mimics prior to small molecule inhibitors to prepare an appropriate background for the specific activity of the second therapeutic. In this way, the non-coding sequence will target the central knot (also targeted by the small molecule inhibitor) but will probably also diminish the levels of additional transcripts involved in the same pathway and other signaling networks (even in drug resistance), due to the heterogeneous profile of targeted genes. The role of miRNA is to prepare the field for the strong effect of the small molecule inhibitor, weakening the cancer cells at multiple levels. After this initial administration, the second agent targeted toward the same central oncogenic molecule will represent the decisive line of treatment in terms of cancer impairment. The sequence of treatment, where miRNA modulator is given as a first agent, is specifically chosen in favor of the other possibilities—concomitant administration or second line of treatment; the ability of miRNAs to target multiple oncogenic targets at once will be used to destabilize the malignant cell, weaken its ability to respond through compensatory feedbacks, and increase the efficiency of the small molecule inhibitor.

By implementing this type of combined strategy, the downsides, like genetic heterogeneity, associated with reduced therapeutic effects and also drug resistance could be strongly diminished. A crucial aspect is also represented by the administrated doses, where the amount of drugs for both type of agents will be significantly reduced proportionally with the occurrence of toxicity events. We mentioned the importance of miRNA mimic or inhibitor doses where, in this particular case, the dose can be lower than the maximum tolerable dosage (MTD). Considering the fact that the role of miRNA is to weaken the cancer cells and prepare the field for the action of the small molecule inhibitor, the doses will be lower than the ones used in the miRNA monotherapeutic approach (it is not followed by the acquisition of a stringent effect, but rather a moderate one). The lack of previous in vivo models for the evaluation of long term toxicity associated with miRNA treatment is currently a stringent issue; once the lowest dose of miRNA mimic or inhibitor that has a strong impairment effect in combination with a small molecule inhibitor is established, the potential toxicity has to be followed throughout a long term interval in immunocompetent animal models that allows the identification of adverse immune reactions. The establishment of the lowest dose needs to be done by evaluation of a wide range of treatment concentrations in vitro, where at least two will be tested in imunocompromised platforms for malignant inhibition to choose the lowest dose with an actual effect. Moreover, long term toxicity events need to be evaluated for miRNA and small molecule inhibitor as single agents and in combination to assess the degree of dependency. Importantly, the possible delayed side effects due to the pyramidal action of miRNAs are also limited in the case of a lower dose; the long term follow up is also a crucial issue for identification of delayed side effects. Another aspect is related to the action of the small molecule inhibitor, because these agents are not as specific as monoclonal antibodies (another type of targeted therapy) and generally interrupt the activity of tyrosine kinases (e.g. epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR], HER2/neu, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] receptor). Even so, the administrated route, usually orally, and also the reduced costs compared to other forms of targeted therapies are favoring their possible use in cancer.21 Therefore, by decreasing the aggressiveness of the cancer cells through prior miRNA administration, the dose of small molecule inhibitor can also be reduced with further benefits regarding the diminishment of off-target effects upon healthy cells (a significant part of malignant tumors overexpress specific molecules targeted by small molecule inhibitors, therefore it is plausible that the active agent will prioritize the cell most abundant in the complementary target; decreased doses also mean less concentration of surplus active agent that can attack healthy cells).

Data also show that there are small molecules able to modulate the expression of miRNAs by targeting the mature sequence or upstream intermediary ones.30 One such strategy is opening the idea of similar approaches with the proposed strategy by using small molecule inhibitors able to modulate miRNAs levels and inhibit central oncogenic knots within the targeted pathways. However, within this kind of approach, the tracking of the modified levels of miRNA becomes more difficult due to the intermediary action of the small molecule inhibitor. Moreover, the advantage of the previous proposed strategy is the ability to administrate significantly smaller doses of exogenous miRNAs for the destabilization of cancer cells (and not complete annihilation) instead of applying a small molecule in higher doses to achieve a modified level of the targeted miRNA.

Practical Example

In one of our previous studies, we established that miR-205 is downregulated in colon cancer patients and cells, with a direct inhibition ability upon ZEB1; in turn, ZEB1 inhibits the levels of CDH1 (E-cadherin), a key epithelial marker associated with the establishment of adherence junctions between cells (also found as downregulated in the same patients). By extrapolation, miR-205 is able to inhibit the process of EMT in colon cancer by impairment of ZEB1 expression and indirect upregulation of CDH1, as shown in our previous article.10 Additionally, miR-205 has, as a direct target, the VEGF transcript, a central molecule for angiogenesis that allows the formation of new blood vessels for the sustenance of cancer cells and also for the migration of the mesenchymal ones.31 VEGF was found as positive in colorectal cancer tissue, with further association with advanced disease and poor prognosis.32 Therapeutic upregulation of miR-205 could be followed by administration of thalidomide, a small molecule inhibitor known for its ability to inhibit tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)33—a gene with inflammatory implications and ability to modulate EMT and cancer invasion;34, 35, 36 TNF-α is also overexpressed in colorectal cancer.37 Moreover, thalidomide is an anti-angiogenic compound that sustains and elevates the action of miR-205 (VEGF inhibition).38

Figure S1 shows the additional miR-205-validated targets, revealing the capacity of this miRNA to influence numerous pathways within cancer cells, including apoptosis through Bcl-2, but also to target simultaneously tumor suppressor genes like PTEN. Therefore, the idea of using miRNA regulators in decreased doses just to induce a destabilization within the cell becomes even more feasible, taking into consideration the multiple targets but also the heterogeneity of the targets in terms of oncogenic or tumor suppressor activity.

What the Future Holds?

A simple search comprising the key words “miRNAs” and “therapy” in the field of cancer will result in an overwhelming number of articles, with numerous miRNAs proposed for therapeutic purposes regarding inhibition of carcinogenesis. The classical approach consists of the modulation of a single miRNA sequence to restore the expression of a specific target gene and sometimes multiple ones to trigger a fatal mechanism for cancer cells. This modulation has been proposed even with the administration of small molecule inhibitors able to modulate the expression of miRNAs—alone or in combination with the actual antisense miRNA.39, 40 But is this mono-target strategy really going to work in actual patients? Considering the heterogeneous character of cancer, the multitude of miRNAs that are actually deregulated in malignant cells, and the ability of cancer cells to develop compensatory mechanisms to avoid the therapeutic insult, we probably need to consider another approach to make the best of miRNA therapeutics. In this sense, the wiser alternative could be represented by the implementation of strategies where miRNAs are used as disruptors of cancer cells and sensitization agents, making the malignant mass more weak and susceptible for the next line of treatment. This approach allows the administration of minimal doses, significantly reducing the possible secondary and toxic effects and also the long term ones that are still unknown in the case of miRNAs. Moreover, the efficiency of the second treatment will significantly increase, even in the case of chemotherapy, due to the ability of miRNAs to target multiple genes and disorganize, to a certain point, the pathological signaling. Not in the least, the experimental character of the combination between miRNAs and small molecule inhibitors can also be subjected to several pitfalls, requiring extensive preclinical optimizations. The difficulty consists mainly in the merged nature of the therapeutic regimen, where side effects associated with both miRNA and small molecule inhibitors need to be evaluated separately and, more laboriously, in combination.

Author Contributions

I.B.-N. and D.G. designed the concept of the present article. D.G. wrote the manuscript, while I.B.-N. critically revised and improved the final version before publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the “Non-invasive intelligent systems for colorectal cancer diagnosis and prognosis based on circulating microRNAs integrated in the clinical workflow” INTELCOR research grant no. 193/2014; PN-II-PT-PCCA-2013-4-1959 and project “MicroRNAs biomarkers of reponse to chemotherapy and overall survival in colon cancer” from the Terry Fox Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes one figure and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2018.07.013.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Dweep H., Gretz N., Sticht C. miRWalk database for miRNA-target interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1182:289–305. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1062-5_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng Y., Croce C.M. The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2016;1:15004. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berindan-Neagoe I., Monroig Pdel.C., Pasculli B., Calin G.A. MicroRNAome genome: a treasure for cancer diagnosis and therapy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014;64:311–336. doi: 10.3322/caac.21244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braicu C., Calin G.A., Berindan-Neagoe I. MicroRNAs and cancer therapy - from bystanders to major players. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:3561–3573. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320290002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulei D., Mehterov N., Nabavi S.M., Atanasov A.G., Berindan-Neagoe I. Targeting ncRNAs by plant secondary metabolites: The ncRNAs game in the balance towards malignancy inhibition. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.11.003. Published online November 10, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redis R.S., Berindan-Neagoe I., Pop V.I., Calin G.A. Non-coding RNAs as theranostics in human cancers. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012;113:1451–1459. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braicu C., Catana C., Calin G.A., Berindan-Neagoe I. NCRNA combined therapy as future treatment option for cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014;20:6565–6574. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140826153529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berindan-Neagoe I., Calin G.A. Molecular pathways: microRNAs, cancer cells, and microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:6247–6253. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulei D., Mehterov N., Ling H., Stanta G., Braicu C., Berindan-Neagoe I. The “good-cop bad-cop” TGF-beta role in breast cancer modulated by non-coding RNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1861:1661–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulei D., Magdo L., Jurj A., Raduly L., Cojocneanu-Petric R., Moldovan A., Moldovan C., Florea A., Pasca S., Pop L.A. The silent healer: miR-205-5p up-regulation inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition in colon cancer cells by indirectly up-regulating E-cadherin expression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:66. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0102-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christopher A.F., Kaur R.P., Kaur G., Kaur A., Gupta V., Bansal P. MicroRNA therapeutics: Discovering novel targets and developing specific therapy. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2016;7:68–74. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.179431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakraborty C., Sharma A.R., Sharma G., Doss C.G.P., Lee S.S. Therapeutic miRNA and siRNA: Moving from Bench to Clinic as Next Generation Medicine. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah M.Y., Ferrajoli A., Sood A.K., Lopez-Berestein G., Calin G.A. microRNA Therapeutics in Cancer - An Emerging Concept. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown R.A.M., Richardson K.L., Kalinowski F.C., Epis M.R., Horsham J.L., Kabir T.D., De Pinho M.H., Beveridge D.J., Stuart L.M., Wintle L.C., Leedman P.J. Evaluation of MicroRNA Delivery In Vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1699:155–178. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7435-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y., Gao D.Y., Huang L. In vivo delivery of miRNAs for cancer therapy: challenges and strategies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;81:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rooij E., Purcell A.L., Levin A.A. Developing microRNA therapeutics. Circ. Res. 2012;110:496–507. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang M.E., Ye Y.C., Chen S.R., Chai J.R., Lu J.X., Zhoa L., Gu L.J., Wang Z.Y. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1988;72:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien S.G., Guilhot F., Larson R.A., Gathmann I., Baccarani M., Cervantes F., Cornelissen J.J., Fischer T., Hochhaus A., Hughes T., IRIS Investigators Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoelder S., Clarke P.A., Workman P. Discovery of small molecule cancer drugs: successes, challenges and opportunities. Mol. Oncol. 2012;6:155–176. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romond E.H., Perez E.A., Bryant J., Suman V.J., Geyer C.E., Jr., Davidson N.E., Tan-Chiu E., Martino S., Paik S., Kaufman P.A. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerber D.E. Targeted therapies: a new generation of cancer treatments. Am. Fam. Physician. 2008;77:311–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abou-Jawde R., Choueiri T., Alemany C., Mekhail T. An overview of targeted treatments in cancer. Clin. Ther. 2003;25:2121–2137. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott U., Downing J.R., Stratton M.R. Genomics and the continuum of cancer care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:340–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0907178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sellers W.R. A blueprint for advancing genetics-based cancer therapy. Cell. 2011;147:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Palma M., Hanahan D. The biology of personalized cancer medicine: facing individual complexities underlying hallmark capabilities. Mol. Oncol. 2012;6:111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrik-Outmezguine V.S., Chandarlapaty S., Pagano N.C., Poulikakos P.I., Scaltriti M., Moskatel E., Baselga J., Guichard S., Rosen N. mTOR kinase inhibition causes feedback-dependent biphasic regulation of AKT signaling. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:248–259. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johannessen C.M., Boehm J.S., Kim S.Y., Thomas S.R., Wardwell L., Johnson L.A., Emery C.M., Stransky N., Cogdill A.P., Barretina J. COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation. Nature. 2010;468:968–972. doi: 10.1038/nature09627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nazarian R., Shi H., Wang Q., Kong X., Koya R.C., Lee H., Chen Z., Lee M.K., Attar N., Sazegar H. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbons D.L., Pricl S., Kantarjian H., Cortes J., Quintás-Cardama A. The rise and fall of gatekeeper mutations? The BCR-ABL1 T315I paradigm. Cancer. 2012;118:293–299. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monroig Pdel.C., Chen L., Zhang S., Calin G.A. Small molecule compounds targeting miRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;81:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salajegheh A., Vosgha H., Md Rahman A., Amin M., Smith R.A., Lam A.K. Modulatory role of miR-205 in angiogenesis and progression of thyroid cancer. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015;55:183–196. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao D., Hou M., Guan Y.S., Jiang M., Yang Y., Gou H.F. Expression of HIF-1alpha and VEGF in colorectal cancer: association with clinical outcomes and prognostic implications. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:432. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singhal S., Mehta J. Thalidomide in cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002;56:4–12. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(01)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bates R.C., Mercurio A.M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulates the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of human colonic organoids. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:1790–1800. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamauchi Y., Kohyama T., Takizawa H., Kamitani S., Desaki M., Takami K., Kawasaki S., Kato J., Nagase T. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha enhances both epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell contraction induced in A549 human alveolar epithelial cells by transforming growth factor-beta1. Exp. Lung Res. 2010;36:12–24. doi: 10.3109/01902140903042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C.W., Xia W., Huo L., Lim S.O., Wu Y., Hsu J.L., Chao C.H., Yamaguchi H., Yang N.K., Ding Q. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by TNF-α requires NF-κB-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Twist1. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1290–1300. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Obeed O.A., Alkhayal K.A., Al Sheikh A., Zubaidi A.M., Vaali-Mohammed M.A., Boushey R., Mckerrow J.H., Abdulla M.H. Increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-αis associated with advanced colorectal cancer stages. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18390–18396. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Amato R.J., Loughnan M.S., Flynn E., Folkman J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4082–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen D., Danquah M., Chaudhary A.K., Mahato R.I. Small molecules targeting microRNA for cancer therapy: Promises and obstacles. J. Control. Release. 2015;219:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu C., Qian L., Uttamchandani M., Li L., Yao S.Q. Single-Vehicular Delivery of Antagomir and Small Molecules to Inhibit miR-122 Function in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by using “Smart” Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015;54:10574–10578. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.