Abstract

Eagle syndrome is an uncommon condition caused by an elongated ossified styloid process. The majority of individuals with an elongated ossified styloid process are asymptomatic. Therefore, this condition is diagnosed based on clinical presentation, with radiologic imaging serving to confirm the diagnosis. The styloid process is considered elongated if measuring greater than 3 cm, but there is little correlation between length of the styloid process and severity of symptoms. This syndrome was originally described in post-tonsillectomy patients, but has since been seen in other clinical settings. We present a case of Eagle syndrome that became symptomatic after a dental procedure (wisdom teeth removal). A literature review performed with focus on various etiologies of Eagle syndrome diagnosis found a previously published case of Eagle syndrome presenting as pain of dental origin;1 however, no case reports of symptoms arising in a patient post-dental procedure were found in our search.

Keywords: Dental procedure, Eagle syndrome, elongated styloid process, wisdom tooth removal

Introduction

An ossified styloid process longer than 3 cm in length may represent Eagle syndrome under appropriate clinical contexts of dysphagia, throat pain, foreign body sensation and referred facial and ear pain. Incidental detection of an elongated styloid process in an asymptomatic patient does not constitute Eagle syndrome. In addition, the typical symptoms described with Eagle syndrome are nonspecific and may be due to reasons other than just the presence of an enlarged styloid process. This is supported by the fact that there a high prevalence of enlarged styloid processes in the general population that is disproportionate to the prevalence of Eagle syndrome. Also, even with bilaterally enlarged styloid processes, symptoms are frequently unilateral.2 A careful physical examination and search for other potential causes even with a radiological finding of an enlarged styloid process is warranted before concluding a diagnosis of Eagle syndrome.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old African American male presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with odynophagia for five days. The pain started approximately two hours following tooth extraction at a dentist’s office. Pain was described as 10/10 in intensity, continuous, sharp, non-radiating, associated with globus sensation, cyclical vomiting and dysphagia. There was worsening of the pain on swallowing, yawning and chewing. Laboratory values upon presentation demonstrated mildly elevated white blood cell count of 11.8 × 103 cells/mcl without left shift. Basic metabolic panel was otherwise unremarkable. On the basis of history and clinical evaluation, peritonsillar abscess and retropharyngeal abscess was suspected, and a computed tomography (CT) exam of the neck soft tissue was ordered. On the CT exam, there was no evidence of peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess (Figure 1). However, the styloid processes of the patient were noted to be elongated, with the left measuring approximately 4.7 cm and the right measuring 4.6 cm (Figure 2). Additionally, multiple calcifications were seen at the tip of the left styloid process with unusual configuration at the superior surface of the left hyoid, suggesting a pseudoarticulation. Although the right styloid was also elongated, it did not reach the hyoid (Figure 3). The patient was admitted, empirically treated for symptoms with oral pain medication and discharged with recommended outpatient follow-up. However, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

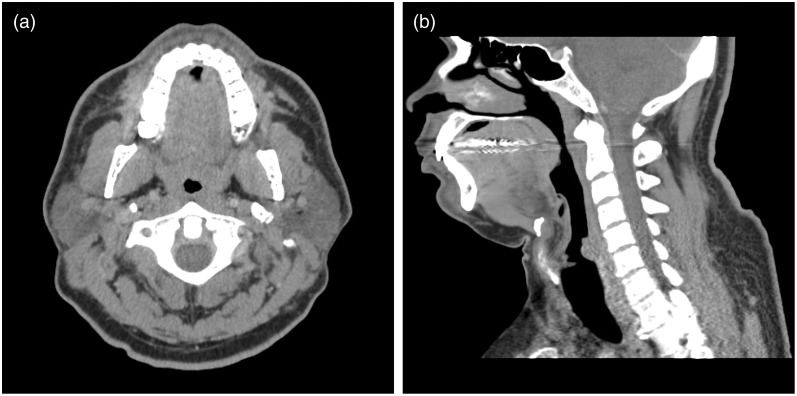

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the neck in soft tissue window. Figure 1(a) is the axial slice at the level of the tonsils, showing no evidence of retropharyngeal abscess or any fluid collection within the masticator space. The parapharyngeal space is also normal bilaterally. Figure 1(b) is the sagittal reformatted image at midline of the neck, again demonstrating normal prevertebral soft tissue with a thin strip of prevertebral fat. There is beam-hardening artifact.

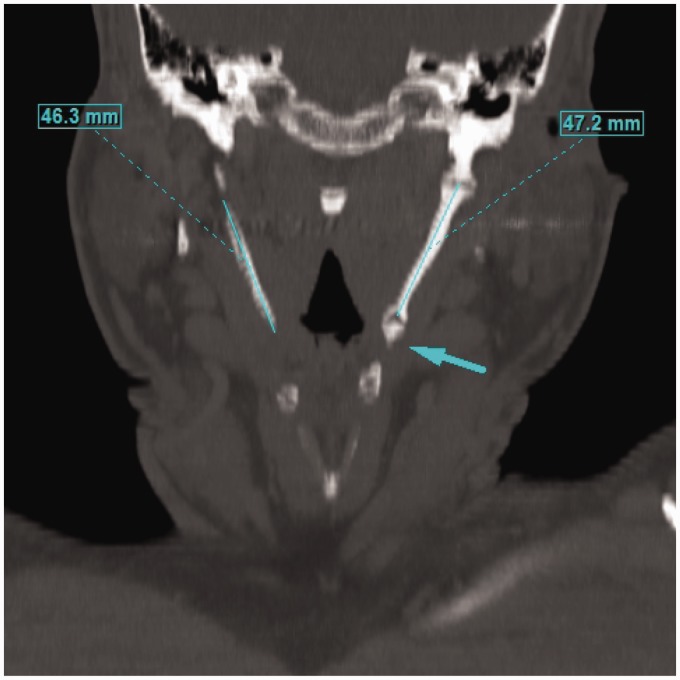

Figure 2.

Multiplanar reconstruction frontal view of the patient’s neck computed tomography in bone window (W/L 2000/500). Measurement of styloid processes showing on image, left = 4.7 cm; right = 4.6 cm. Arrow indicates partially visualized ossified pseudoarticulation of the left styloid with the superior aspect of the left hyoid.

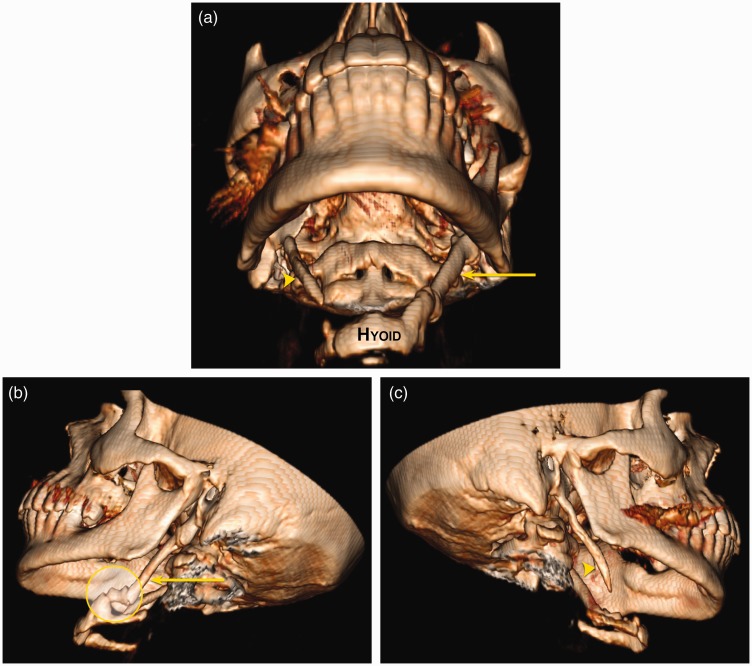

Figure 3.

Multiple three-dimensional volume-rendered images with soft tissue segmented and removed. Both elongated styloid processes are seen in Figure 3(a) (left styloid process: arrow, right styloid process: arrowhead), in close proximity to the hyoid bone. Figures 3(b) and 3(c) are oblique images showing each elongated styloid process individually. The abnormal configuration of the superior aspect of the hyoid bone with pseudoarticulation to the left styloid process is seen in Figure 3(a) and 3(b) (yellow circle).

Discussion

The styloid process is a thin bony projection of the temporal bone extending inferiorly. It connects with lesser cornua of the hyoid bone through the stylohyoid ligament.3 This combination of anatomical structures is known as the stylohyoid apparatus.4,5 If the styloid process is more than 3 cm in length, it is considered abnormally elongated.6 It is frequently associated with an ossified stylohyoid ligament. The overall prevalence of an elongated styloid process is said to range from 2% to 30% in adults. Only less than 0.5 percent of those having an enlarged styloid process will be symptomatic, suggesting poor correlation between radiographic and clinical findings.5 There is very little correlation between severity of symptoms and the severity of ossification.7

Current literature theorizes that an enlarged styloid process can impinge and irritate the 5th, 7th, 10th and 11th nerve with resulting recurrent throat pain, dysphagia, sensation of foreign body in the throat, referred facial pain and referred ear pain.8 On clinical exam, an ossified stylohyoid ligament can be palpated and tenderness can be elicited.

Eagle first described this entity in 1937, dividing it into two subtypes: “classic syndrome” and “stylocarotid artery syndrome.”9 It is more common in women.4 Originally, Eagle syndrome was described in a post-tonsillectomy setting, presumably due to scarring in the tonsillar fossa in the vicinity of the stylohyoid apparatus. Currently, this is no longer a prerequisite but rather a constellation of findings that can be seen in other scenarios. For example, fracture of the styloid process and/or an ossified stylohyoid ligament can be clinically symptomatic.9 A review of the literature found several cases of Eagle syndrome presenting as a result of blunt trauma such as motor vehicle crash, fall and assault.10 Another theory suggests degenerative and inflammatory changes in the tendonous portion of the stylohyoid insertion as a trigger for symptoms.11

In addition, an enlarged styloid process can compress the adventitia of the external and internal carotid arteries and irritate underlying nerve endings causing facial pain. This entity is sometimes considered a separate set of pathology under carotidynia.5 Rare cases with Eagle syndrome resulting in carotid artery dissection as well as transient ischemic attacks with ipsilateral head rotation have also been reported.12,13 There are two reported cases of sudden death that have forensically been attributed to cerebrovascular accidents related to Eagle syndrome.14,15

Eagle syndrome can be treated both non-surgically and surgically. Non-surgical treatment options include steroid injection and analgesic medications. Surgical resection can be via an intraoral or extraoral approach.16,17 Pros of transoral approach are minimal scar formation, fewer complications and being less time consuming. Cons are poor visibility and greater risk of deep neck infection. Pros of extraoral are excellent visibility. Cons are scar and possibility of facial nerve injury. Even after surgery, there is an estimated 20% recurrence of the symptoms of the facial pain.5

Overall, the signs, symptoms and imaging findings of Eagle syndrome are not very specific and other oral, dental and temporomandibular joint pathologies should be kept under differentials.18 However, this is an important entity to consider as a part of the differential in patients who have undergone dental procedures presenting with neck pain.9 As noted above, Eagle syndrome may also masquerade as dental pain.19

The specific diagnosis of Eagle syndrome should be considered with the appropriate clinical presentation and styloid process of longer than 3 cm. Radiologically, plain film, CT and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction are all tools that can be used in diagnosis. CT is superior in that it offers the ability to visualize and prepare 3D reconstructions for surgical reference.11

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Jennifer H. Lee, MFA, for her assistance.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Aral IL, Karaca I, Güngör N. Eagle’s syndrome masquerading as pain of dental origin. Case report. Aust Dent J 1997; 42: 18–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeckler SR, Betancur AG, Yaniv G. The eagle is landing: Eagle syndrome—an important differential diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62: 501–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville B, Damm DD, Allen C, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 4th ed. Chapter 1. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2016.

- 4.Langlais RP, Miles DA, Van Dis ML. Elongated and mineralized stylohyoid ligament complex: A proposed classification and report of a case of Eagle’s syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986; 61: 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedlar J and Frame J. Oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2nd ed. Section III, Chapter 52. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2009, pp.969-970.

- 6.Piagkou M, Anagnostopoulou S, Kouladouros K, et al. Eagle’s syndrome: A review of the literature. Clin Anat 2009; 22: 545–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savranlar A, Uzun L, Uğur M, et al. Three-dimensional CT of Eagle’s syndrome. Diagn Interv Radiol 2005; 11: 206–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Som PM and Curtin HD. Head and neck imaging. 5th ed. Chapter 42. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby, 2011, p.2726.

- 9.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process. Report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1937; 25: 584–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann A, Wood C, Carter R, et al. Eagle syndrome presenting after blunt trauma: A case series. J Vasc Surg 2016; 63: 297–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with Eagle syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 1401–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subedi R, Dean R, Baronos S, et al. Carotid artery dissection: A rare complication of Eagle syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2017; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Farhat HI, Elhammady MS, Ziayee H, et al. Eagle syndrome as a cause of transient ischemic attacks. J Neurosurg 2009; 110: 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clément R, Barrios L. Eagle syndrome and sudden and unexpected death: Forensic point of view about one case. J Forensic Res 2014; 5: 230. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar P, Rayamane AP, Subbaramaiah M. Sudden death due to Eagle syndrome: A case report. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2013; 34: 231–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blythe JN, Matthews NS, Connor S. Eagle’s syndrome after fracture of the elongated styloid process. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 47: 233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beder E, Ozgursoy OB, Karatayli Ozgursoy S. Current diagnosis and transoral surgical treatment of Eagle’s syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 1742–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fini G, Gasparini G, Filippini F, et al. The long styloid process syndrome or Eagle’s syndrome. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2000; 28: 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zohar Y, Strauss M, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome masquerading as pain of dental origin. J Maxillofac Surg 1986; 14: 294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]