Abstract

Schistosomiasis is the second most common parasitic infection worldwide. North America is a nonendemic area. However, there are occasional case reports among travelers and immigrants from endemic regions. We describe a case of a 55-year-old Canadian woman who presented with first episode of seizure. Her magnetic resonance imaging scan revealed a mass-like lesion involving the left anterior temporal lobe. The lesion showed T1 hypo- and T2 hyperintense with perilesional brain edema. On post-gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequence, the lesion showed multiple small nodular and linear enhancements, also called an “arborized” appearance. Initially, the lesion was thought to be a malignant tumor. She underwent left anterior temporal lobe resection. Histologic examination showed parasitic eggs with a characteristic lateral spine consistent with Schistosoma mansoni infection. Upon subsequent questioning, it was revealed that the patient lived in Ghana from the ages of 8–10 years and she visited Ghana again 10 years prior for two weeks. She recalled swimming in beaches and rivers. Latent disease, as in this case with presentation, many years or decades after presumed exposure is rare but has been reported. Characteristic magnetic resonance imaging findings may suggest the diagnosis and facilitate noninvasive work-up.

Keywords: Arborized appearance, cerebral schistosomiasis, granuloma, magnetic resonance imaging, tumor-like lesion

Introduction

Schistosomiasis is one of the most common parasitic infections in humans. More than 200 m people in 77 countries are infected worldwide.1,2 The disease is caused by digenetic blood trematodes of the genus Schistosoma, of which the three main species are S. haematobium, S. mansoni, S. japonicum.1

The geographic distribution of the different species depends on the existence of certain species of freshwater snails, which act as intermediate hosts. S. mansoni and S. haematobium are endemic in Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and South America whereas S. japonicum is endemic in the Far East.1,2 Although North America is not an endemic region, the disease has been occasionally reported among travelers and immigrants from endemic areas.3–6

Schistosomiasis infection occurs following skin exposure to infected freshwater, typically when swimming. Schistosoma cercariae depart from snails living in contaminated freshwater and penetrate the skin, occasionally producing dermatitis (“swimmer’s itch”) lasting for several days. Over several weeks, the parasites migrate into the mesenteric venous system of the host to develop into adult worms. Once mature, the worms mate and females produce eggs. Some of these eggs travel to target organs, commonly the bladder, intestines, and liver, and are passed into the urine or stool.2 Less commonly, they affect the central nervous system (CNS).

We report the case of 55-year-old Canadian female patient presenting with a tumor-like brain lesion, with pathological findings consistent with S. mansoni infection. The patient presented many years after presumed exposure.

Case report

A 55-year-old Canadian female presented with worsening left sided headaches for three months and a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. She went to a community hospital, where the initial work-up found an intracerebral mass-like lesion, thought to be a malignant brain tumor. She was subsequently referred to our hospital for treatment. On physical examination, there were no focal neurological deficits. The routine complete blood cell count, routine chemistry, and urinanalysis were normal. Her chest radiograph showed no abnormal findings.

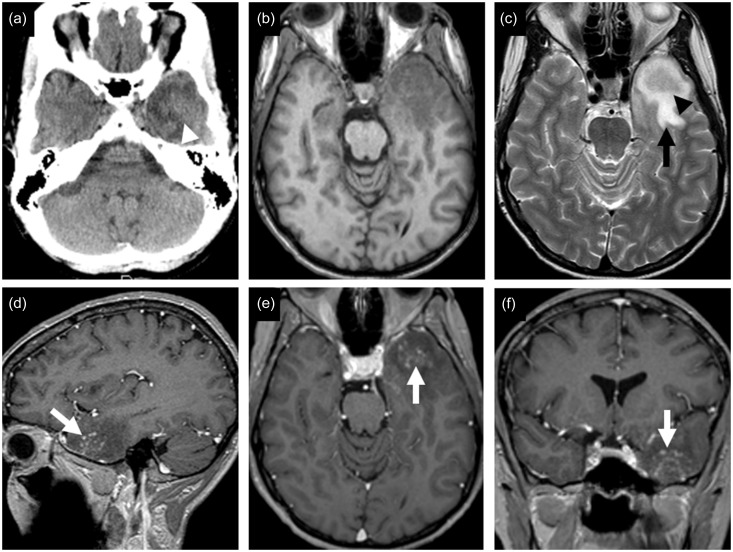

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed an intermediate density mass with surrounding hypoattenuated area of brain edema in left anterior temporal lobe (Figure 1(a)). No calcifications were found. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted images and intermediate signal on T2-weighted images, with surrounding edema and mass effect (Figure 1(b) and (c)). On post-gadolinium T1-weighted sequence, the lesion demonstrated linear and punctate nodular enhancement (Figure 1(d)–(f)).

Figure 1.

CT and MRI findings. The mass-like lesion in the left anterior temporal lobe shows intermediate density (white arrowhead) with surrounding hypoattenuated area of brain edema on non-contrast-enhanced CT scan (a). The lesion shows hypointense signal on T1-weighted image (b), and intermediate signal (black arrowhead) with abnormal high signal of surrounding brain edema (black arrow) on T2-weighted image (c). Multiple central linear and nodular enhancing areas, giving an “arborized” appearance (white arrows), are shown on post-gadolinium T1-weighted images (d)–(f). CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

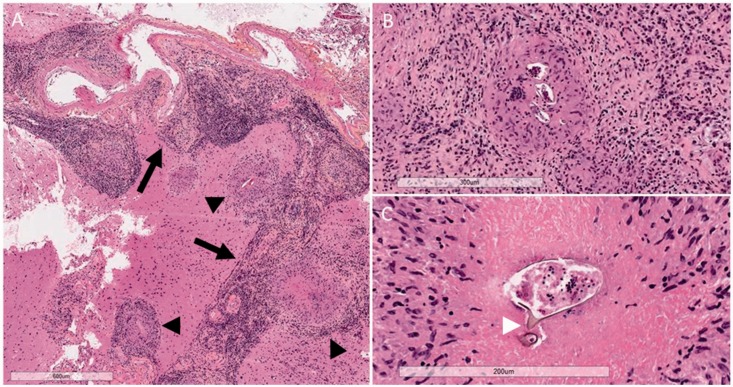

The patient underwent left anterior temporal lobectomy for debulking of the lesion. Histological examination revealed granulomatous inflammation in the brain parenchyma and leptomeninges, composed of organized collections of epithelioid histiocytes with central necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional eosinophils (Figure 2(a) and (b)). The center of these well-formed granulomas often contained ovoid parasitic eggs, consistent with Schistosoma species (Figure 2(b)). Some eggs showed a distinctive lateral spine (Figure 2(c)), suggestive of S. mansoni.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of histopathological findings (hematoxylin phloxine saffron stain): (a) an intense granulomatous inflammatory reaction involving the brain parenchyma and leptomeninges (5×). The inflammatory infiltrate follows leptomeningeal veins in the subarachnoid space in a linear fashion (arrow) with granulomatous inflammation adjacent to these areas (arrowheads); (b) Schistosoma ova, sometimes multiple, within the center of granulomas (10×); (c) some ova demonstrate a distinctive lateral spine (white arrowhead) (20×).

The inflammatory infiltrate followed the leptomeningeal veins and extended into the brain parenchyma via superficial cortical veins. Focally, individual or clusters of granulomas were situated directly adjacent to the linear arrangements of perivascular inflammatory infiltrates (Figure 2(a)).

Subsequent questioning of the patient revealed that the patient was born and currently lived in Toronto, Canada but lived in Ghana from the ages of 8–10 years. During that period, she recalled having a parasitic infection that was presumably treated. She subsequently vacationed in Ghana 10 years prior to presentation for a duration of two weeks. She recalled drinking bottle water, but did eat at local restaurants and swam in local beaches and rivers.

A repeated physical examination and abdominal ultrasonography performed post-operatively revealed no abnormalities. No ova or parasites were found in urine or stool. Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was positive for Schistosoma species with an optical density (OD) of 1.31.

The patient was treated with oral praziquantel 60 mg/kg in two divided doses and retreated in one month’s time, with oral prednisolone and phenytoin. On clinical follow-up, the patient’s symptoms improved and she had no further seizure activity. Subsequent brain imaging showed no residual lesion with resolution of brain edema.

Discussion

Neuroschistosomiasis denotes the symptomatic or asymptomatic involvement of the CNS by Schistosoma species.7 Cerebral involvement tends to be more common in S. japonicum, while spinal cord involvement, also called schistosomal myeloradiculopathy, is more common in S. mansoni and S. haematobium.5,7 Although rare, cerebral involvement with S. mansoni has been reported.3,4,6,8

Regarding the pathogenesis of neuroschistosomiasis, it has been postulated that the ova may reach the CNS through retrograde venous flow into the Batson vertebral epidural venous plexus, which connects the portal venous system to the spinal cord and cerebral veins. This route permits either anomalous migration of adult worms to sites close to the CNS followed by in situ oviposition, or massive embolization of eggs from the portal mesenteric venous system.9–11 Once deposited in the nervous tissue, the embryo excretes antigenic and immunogenic substances that account for the periovular granulomatous reaction.

Common clinical manifestations of cerebral schistosomiasis include headache, seizure, alteration of consciousness, and focal neurological deficit depending on the site of the lesions.12 Duration of symptoms varies from a few weeks to more than one year.13

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of cerebral schistosomiasis characteristically show single or multiple mass-like lesions usually involving cortex and subcortical areas in the cerebral hemispheres, or less commonly the cerebellum and brain stem.12,14 On contrast-enhanced MR imaging, the lesions typically show a unique enhancement pattern of clusters of central linear enhancement surrounded by multiple enhancing punctate nodules, also called an “arborized” appearance, which may be specific for cerebral schistosomiasis.12,14–16 Previous literature3 suggested that linear enhancement may be the result of worms causing local leptomeningeal venous obstruction and slow blood flow. We would speculate that linear enhancement simply represents inflammatory infiltrates following the leptomeningeal veins in the subarachnoid space and superficial veins in the cortex (Figure 2(a)). The inflammation is presumably induced by eggs as they exit the venous system. When eggs become encased by granulomas, which sometimes may occur in clusters, this would correspond to nodular enhancement. In other words, the intravascular-extravascular migration of Schistosoma eggs produces a pattern of inflammation, and thus contrast enhancement, that mirrors the hierarchical branching pattern of leptomeningeal and superficial cortical veins. Hence, this would correspond to an “arborized” pattern of enhancement on MRI. When eggs become associated with granulomatous inflammation after extravasation, this would appear as nodular enhancement adjacent to the arborized/linear/perivascular enhancement.

When suspected, diagnosis of neuroschistosomiasis can be made noninvasively in several ways. Urine or stool examination for eggs can be positive in up to 50% of neuroschistosomiasis patients, but can be falsely negative.11 Immunological tests can be performed in serum or cerebrospinal fluid. A combination of indirect hemagglutination (IHA) test and ELISA is considered highly sensitive and specific for active disease with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 92.9%.17 Ultimately, a definitive diagnosis can be made if parasite eggs are present in tissue.10,11

Our case highlights several important points. First, the travel and social history can have important implications, but this was overlooked initially. This patient was presumably infected 10 years ago during her last visit to Ghana, where S. mansoni is endemic or, less likely, 45 years ago when she was a child. Untreated individuals can live with schistosomes for a long time.18 Giboda et al. suggested the term “post transmission schistosomiasis” to define disease or persistent infection in individuals who move from an endemic area to a nonendemic area.18 The latent period of infection of S. mansoni is variable and has been reported from 5.7–40 years after exposure.18,19 Second, MR imaging findings of schistosomiasis can have a unique appearance, which may permit the diagnosis to be entertained and noninvasive workup initiated.6

Neuroschistosomiasis can be successfully treated with oral praziquantel with a dose of 40–60 mg/kg per day orally in two divided doses for one day with a possible repeat treatment 2–4 weeks later to increase effectiveness.2 An oral corticosteroid helps to reduce inflammation.11 Antiepileptic drugs may be needed to treat symptomatic seizure. Surgery may be required for management of severe mass effect (rare), hydrocephalus, or for definitive diagnosis when required.11

Conclusion

Cerebral schistosomiasis is rare, especially in North American patients. However, it can occur in patients who have travelled to endemic areas. The diagnosis can be confounded by long latency between exposure and active disease and by the mass-like appearance simulating neoplasm. A unique enhancement pattern on MRI can suggest the diagnosis.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, et al. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 2006; 368: 1106–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis, 2016. http://www.who.int/schistosomiasis/en/ (accessed 11 November 2016).

- 3.Gjerde IO, Mork S, Larsen JL, et al. Cerebral schistosomiasis presenting as a brain tumor. Eur Neurol 1984; 23: 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie IR, Guha A. Manson's schistosomiasis presenting as a brain tumor. Case report. J Neurosurg 1998; 89: 1052–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houston S, Kowalewska-Grochowska K, Naik S, et al. First report of Schistosoma mekongi infection with brain involvement. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: e1–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose MF, Zimmerman EE, Hsu L, et al. Atypical presentation of cerebral schistosomiasis four years after exposure to Schistosoma mansoni. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep 2014; 2: 80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrari TC. Involvement of central nervous system in the schistosomiasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2004; 99: 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero F, Zanini M, Ducati L, et al. Pseudotumoral form of cerebral Schistosomiasis mansoni. J Surg Case Rep 2012; 2012: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pittella JE. Neuroschistosomiasis. Brain Pathol 1997; 7: 649–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carod-Artal FJ. Neuroschistosomiasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2010; 8: 1307–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross AG, McManus DP, Farrar J, et al. Neuroschistosomiasis. J Neurol 2012; 259: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu L, Wu M, Tian D, et al. Clinical and imaging characteristics of cerebral schistosomiasis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2012; 62: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nascimento-Carvalho CM, Moreno-Carvalho OA. Neuroschistosomiasis due to Schistosoma mansoni: A review of pathogenesis, clinical syndromes and diagnostic approaches. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2005; 47: 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Lim CC, Feng X, et al. MRI in cerebral schistosomiasis: Characteristic nodular enhancement in 33 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191: 582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanelli PC, Lev MH, Gonzalez RG, et al. Unique linear and nodular MR enhancement pattern in schistosomiasis of the central nervous system: Report of three patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177: 1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shih RY, Koeller KK. Bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections of the central nervous system: Radiologic-pathologic correlation and historical perspectives. Radiographics 2015; 35: 1141–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Gool T, Vetter H, Vervoort T, et al. Serodiagnosis of imported schistosomiasis by a combination of a commercial indirect hemagglutination test with Schistosoma mansoni adult worm antigens and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with S. mansoni egg antigens. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40: 3432–3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giboda M, Bergquist NR. Post-transmission schistosomiasis: A new agenda. Acta Trop 2000; 77: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vieira P, Miranda HP, Cerqueira M, et al. Latent schistosomiasis in Portuguese soldiers. Mil Med 2007; 172: 144–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]