Abstract

Background:

Family caregivers of patients with mental disorders play the most important role in the care of psychiatric patients (PPs) and preventing their readmission. These caregivers face different challenges in different cultures. We conducted this study to determine the challenges of caregivers of patients with mental disorders in Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a narrative review with a matrix approach conducted by searching electronic databases, SID, IRANMEDEX, MAGIRAN, PUBMED, SCOPUS, Web of Sciences, from February 2000 to 2017. Searched keywords include challenges, family caregivers of psychiatric patient, family caregivers and psychiatric patient, mental illness, families of psychiatric patient, and Iran. One thousand two hundred articles were found in English and Farsi, and considering inclusion and exclusion criteria, 39 articles were examined.

Results:

The results of the studies show that not meeting the needs of caregivers, burnout and high burden of care, high social stigma, low social support for caregivers, and low quality of life of caregivers were among the most important challenges faced by caregivers.

Conclusions:

Despite the efforts of authorities in Iran, family caregivers of patients with mental disorders still face challenges. Therefore, the need for all-inclusive support for family caregivers of patients with mental health problems is necessary.

Keywords: Caregivers, Iran, literature review, mental disorders

Introduction

Among medical diseases, psychiatric disorders have a high prevalence and are a significant burden. According to the most recent meta-analysis, the average prevalence of mental disorders in the world is 13.4%,[1] and 30–50% of psychiatric patients (PPs) experience relapse of symptoms in the first 6 months and 50–70% in the first 5 years after discharge from the hospital.[2],[3],[4] Due to deinstitutionalization of the treatment and care of PPs, the role of family caregivers of these patients is important in reducing the number of hospital admissions.[5] Family caregivers of PPs while being able to manage and control the patient and their disease play a vital role in maintenance and rehabilitation of patients.[6] Thus, family caregivers of PPs suffer great pressure physically, mentally, and socially in the course of care and control of the sick members of the family.[7],[8]

In fact, patients and their families are constantly affected by the changes resulting from the disease and its treatment. These changes gradually reduce the levels of performance and the ability of family members, destruction of emotional system and communication structures of family, ineffective relationships among members, emergence of financial and economic problems, reduced social interactions of the family, changes in roles, reduced life expectancy, and emergence of symptoms such as anger, feeling guilty, grief, and even denial.[9],[10]

Overall, mental burden of care for a PP while reducing the quality of life of caregivers can jeopardize their physical and mental health, and ultimately lead to poor care, leaving the treatment, or violent behavior with patients and these problems can exacerbate disorder in patients.[5],[11] Thus, if caregivers are left without adequate social support, they can also be considered as hidden patients.[12]

Studies show that the status of caregivers of patients with mental disorders has been neglected in in some countries. Although some of the needs and challenges for caregivers and family members of patients may be common with the patients, they have unique needs with many uncertainties.[13] On the other hand, many doctors and health care workers, particularly psychiatric nurses, often focus their care more on the patient and ignore the family and main caregivers of the patient. These doctors and nurses exclude them from the disease, treatment, and decision-making processes and do not consider their needs; hence, families do not have a chance to express their concerns and needs and are at a risk of serious problems.[14] By identifying the problems and challenges of the caregivers of the patient's admission to hospital, psychiatric nurses can plan for their issues and problems.

Although numerous studies have been conducted on family caregivers of mentally ill patients in Iran, a comprehensive overview and scientific study has not been conducted to determine their challenges. Therefore, in this study, scientific evidences and other relevant documents were reviewed to capture the challenges of caregivers of patients with mental health problems in the Iranian context.

Materials and Methods

This is a narrative review study using a matrix approach in 2017. A review study includes a summary of previous findings in the literature review of research on a particular topic.[15] The existence of a wealth of information is both an opportunity and a challenge. A systematic method of review is needed for these texts to be used with full performance to overcome this challenge. Therefore, we used the matrix method[15] to achieve the study objectives.

Initially, a team consisting of nursing faculty members of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran and a librarian were arranged. Literature search was carried out by the principal author (M.A). The extracted documents were reviewed by other researchers independently to include relevant and appropriate documents in the study.

The search took place in electronic databases SID, IRANMEDEX, MAGIRAN, Google scholar, PUBMED SCOPUS, Web of Sciences, in English and Persian, from 2000 to 2017 with the following keywords – family caregivers of PPs, family caregivers and PPs, family of PPs, and Iran. A librarian helped in literature search. Finally, 1200 published documents (i.e., 1100 papers, 45 theses, and 55 books) related to the challenges of family caregivers of PPs in Iran were retrieved.

Relevant MeSH terms and keywords were used to ensure selected articles included search terms pertaining to (a) family caregiver and/or mental health disorders; (b) challenge and/or problem; (c) caregivers with psychiatric patient; and (d) Iran. Results were combined using the “AND” Boolean operator to ensure inclusion of at least one search terms from each of the four categories. Retrieved articles were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria in this study included national studies exploring the challenges of family caregivers of patients with mental health disorders. Participants were family caregivers of patients with mental health disorders of all ages. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included editorial and review articles, book chapters, preliminary or pilot studies, and studies with the primary focus on the patient and not family caregivers.

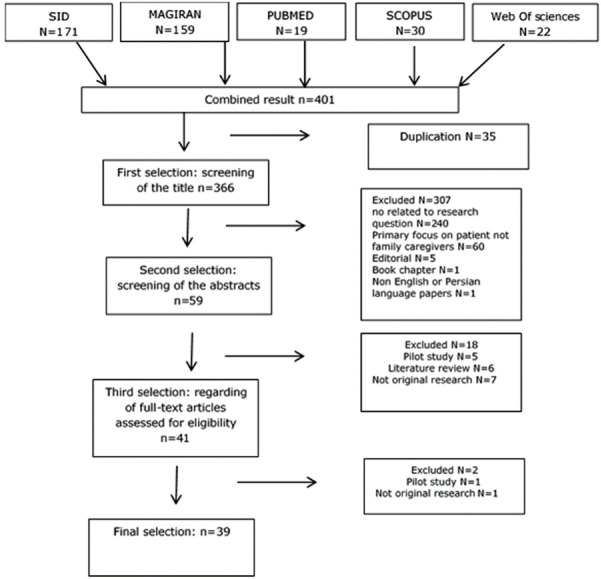

Studies with relevant titles and abstracts were included in the analysis. Relevant articles were then subjected to critical appraisal which involved assessing the methods and results sections to find their strengths and weaknesses as well as their relevance to the review question. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, the reference lists of the selected articles were hand searched for related records, yielding a total of 39 articles for the final review [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Matrix pattern of step by step review

All retrieved articles were read several times by one author and reviewed by the second author to gain a deeper understanding of the studies.

Data were extracted based on the date of publication and sample setting. Core features of analysis were (a) whether the study focused specifically on the challenge or problem in Iranian family caregiver of mental health disorders; (b) whether the study was aimed at the family caregiver or family or both; (c) outcome measures; (d) methods; (e) content; and (f); results. Then, based on common meanings and central issues of these findings, they were organized and integrated as categories and themes.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan Iran (ethical approval code: IR.MUI.REC.1395.3.250). The included studies were checked to ensure respecting the participants' consent.

Results

Of the 39 included studies, 3 were conducted before 2005, 10 from 2005 to 2010, and 26 from 2010 to February 2017. Of these, 21 studies were conducted in a cross-sectional manner in 12 provinces of Iran using convenience sampling with 4582 samples. Ten articles were conducted using an interventional mode with 512 participants and 8 adopted a qualitative approach with 170 caregivers; their findings could explain the conditions of caregivers of patients with mental disorders. These studies used a variety of standard and researcher-developed tools.

After completing the review process, the data were extracted as codes of topics relevant to the review question and were qualitatively categorized by the research team members to find main themes. The challenges of family caregivers of PPs in Iran were specified as (a) not meeting the needs of caregivers, (b) burnout and high burden of care, (c) high social stigma, (d) low social support for caregivers, and (e) low quality of life of caregivers.

Not meeting the needs of caregivers

One of the main challenges for family caregivers of PPs is not meeting their needs. Shamsaei et al. studied the needs of family caregivers of PPs in the cultural context of Iran in a qualitative study. One hundred six contents were extracted from the statements of family caregivers of PPs and classified in five main themes – illness management, consulting, economic needs, continuous care, and attention and understanding of the society. Thus, educational, economic, and moral supports were among the most important unmet needs of these caregivers.[16] In another qualitative study by Shamsaei et al., the need of caregivers to information was one of the main challenges.[17]

In the study by Zeinalian et al. (2011), four problems and needs that most caregivers considered serious included lack of sufficient information for the rehabilitation of patients (98%), despair and suffering of caregivers due to chronic disease (94%), communication problems with patients (92%), and not enough time of caregivers (88%).[18]

Behpajuh et al. showed that the most critical need of caregiver mothers was information about the training process and participation in educational programs and the treatment of their children. Most problems of autistic children were in the areas of speech, social interaction and emotional problems, attention and focus, issues of family, and career.[19]

Currently, the efforts of health authorities in Iran are towards caring for PPs at home beside family members and continuing treatment and care in the family environment. Therefore, identifying and meeting the needs of the family caregivers of PPs help the mental health care team apply proper care interventions to help caregivers and help them in their care.

Burnout and high care burden

Another important challenge of family caregivers of PPs in Iran is burnout and high care burden. In the study by Navidian et al., 26.4% of the caregivers had mild, 60.8% moderate, and 12.8% high mental pressure, i.e., a total of 73.6% of family caregivers had moderate-to-high mental pressure.[7] Cheemeh et al. showed that the average burnout of caregivers of male patients was significantly higher than the burnout of caregivers of female patients (24.31 versus 20.25). General health score of caregivers of single patients was lower than the score of caregivers of married patients, and caregivers of employed patients had better mental health (28.69 versus. 21.28).[20]

In the study by Sharif et al., the score of burden of care of caregivers was 18.66 and reached 11.44 after psychological intervention.[21] In a study Shamsaei et al. examined the meaning of health from the perspective of family caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. In data analysis, six main themes –living hell, psychological burnout, self-neglect, need for support, condemned to isolation, and shame – were extracted. All participants reported feelings of sadness, internal suffering, lack of joy, despair, and emptiness in their experiences.[22]

Saleh et al. (2014) obtained a moderate score of social health of caregivers of veterans, 12.59. Moreover, 18.8% of these caregivers have had very high social health – 22.6% high, 17.6% moderate, 21.6% low, and 15.5% very low.[23]

Abdollahpour et al. obtained the average care burden of family caregivers caring for patients with dementia (55.2), implying that the burden of care providers in more than 50% of the caregivers of these patients (score of burden of care 58–116) was moderate to severe.[24]

In their study, Navidian et al. mentioned the burden of caring of 73.6% of caregivers of PPs as moderate to severe.[25] In another study, Shamsaei et al. examined the burden of caring of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Iran; 7.6% of the caregivers had no burden of care or had very mild form of it, 23.5% had mild to moderate, 41.8% moderate to severe, and 27.1% had severe burden of care.[26] Hosseini et al. found that 35% of caregivers had a score of GHQ >23.[27]

As studies showed care pressure of caregivers of mentally ill patients is high, and it is possible that these pressures reduce the level of patient care and jeopardize the physical and mental health of the caregiver.

High social stigma

Stigma is considered as one of the major challenges of caregivers. Vagei et al. (2015) obtained the mean (SD) score of stigma in families of patients with schizophrenia 42.6 (9.2) (out of 68), where the highest mean was for withdrawal from society 12.4 (3.3) and the lowest was for loneliness 9.8 (3).[28] In the qualitative study of Shamsaei et al., experiences of family caregivers of mentally ill patients in Iran were in three main themes – negative judgment, shame, stigma and social isolation.[29] Sadeghi et al. (2004) showed that 49% of caregivers for schizophrenia, 30% of people from major depressive disorder (MDD) group, and 50.5% of bipolar group were complaining about discrimination and ridicule because of PPs in the family.[30]

In their study, Shah et al. concluded that 45% of the caregivers of schizophrenic patients and 32.5% of depression group were ridiculed and discriminated against.[31]

Families and those without mental illness (especially at an early age, particularly at the school level) should be aware of how compassionate kindness leads to stigma and discrimination and pose obstacles among caregivers and family of PPs.

Low social support for caregivers

Social support for caregivers of patients with mental disorders can be evaluated in four areas, including social support, information support, moral support, and support for family caregivers of war veterans.

Social support

One of the very important issues and important responsibilities of all members of society is social support of these caregivers because studies show that the social support for this group is low. Saleh et al. (2014) showed that 6.8% of these caregivers have very high social protection, 38.5% high, 21.5% moderate, 18.5% low, and 15% very low.[23]

Beirami et al (2014) showed that social support score in women taking care of their spouses with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (28.16) is than normal people (33.28).[32]

Information support

Other studies in Iran show information support for these caregivers. In other words, these caregivers have insufficient information about self-care and patients. Mami et al. carried out a program of psycho-education support for families of PPs, which led to increased mental health, social functioning, reduced anxiety, and depressive symptoms; however, the program had no significant effect on decreasing the physical symptoms of caregivers.[33]

The results of Sheikh al-Islami et al. illustrates that the average score of psychological well-being before training was 224 and after training was 373, i.e. training the skills of dealing with stress affects the familial mental health of families of people with mental disorder.[34]

In two studies, Karamlou et al. (2010) showed that psycho-education of families of people with severe mental disorders has no positive effects on their family environment. Family psycho-education increases expressiveness, mental state, and family solidarity, but it does not change the conflict component.[35]

In a study, Sharif et al. reported that psychological training program for families of PPs has a significant impact on psychological symptoms (score 4.78 versus. 3.13) and care burden (score 18.66 versus. 11.45).[36] Studies by Pahlavanzadeh, Mottaghipour, and Koolaee reported similar results.[37],[38],[39]

In the study by Omranifard et al., average score of the pressure imposed on family in the intervention and control groups in none of the three periods, at the beginning of the intervention, 3 months after the intervention, and 6 months after the intervention, had no significant differences. Nevertheless, the quality of life in the intervention group 6 months after the intervention had significantly increased.[40]

According to these studies, low information of family caregivers of patients with mental disorders in Iran is evident. Comprehensive support of caregivers is one of the requirements and one of the main tasks of all individuals and organizations in Iran.

Spiritual support

Another aspect of the protection of these caregivers is spiritual support and some texts have referred to them. Sharifi et al. studied the relationship between the religious commitment of family caregivers of Iranian context and consequences of care. Positive religious coping (tendency to religion), indicating a sense of spirituality, safe relationship with God, belief meaningfulness of life, and spiritual relationship with others, has positive outcomes such as higher self-esteem, better quality of life, psychological adjustment, and more spiritual growth in relation to tension. However, negative religious coping (turning away from religion) represents less safe relationship with God and an uncertain and pessimistic view of the world and has negative consequences such as depression, emotional distress, and lack of physical health, low quality of life, and weak problem solving.[41]

Although Iranian society has entered industrialization, along with these changes, religious beliefs and values have preserved their character. Thus, caregivers with greater moral support have higher mental health that should be considered by authorities in support of caregivers.

Support for family caregivers of mental veterans of war

Some studies have been conducted on caregivers of mental veterans in Iran. Noghani et al. (2016) conducted a study on PTSD veterans' wives and found perceived social support, severity of PTSD of the spouse, and family economic status as factors affecting (64%) the quality of life of the caregivers.[42]

Saleh et al. obtained the average score of social support for caregivers of veterans (21.2); the most important sources of social support were family members followed by relatives and friends. Of these caregivers, 6.8% have very high social support, 38.5% high, 21.2% moderate, 18.5% low, and 15% very low.[23] Beirami et al. showed that social support score in the women taking care of husbands with PTSD (28.16) was less than that of normal people (33.28).[32]

However, family caregivers of mental veterans still have problems and challenges because the sanctity and culture of sacrifice are supported more than other caregivers by both official and nonofficial sources.

Low quality of life

Aali et al. showed that the mean scores of developmental functioning of families of autistic children is less than that of normal children (67.06 versus 80.65). In addition, regarding interest and attraction to human relationships, solving common social problem, logical thinking, and discipline, their findings showed significant differences between developmental functioning of the family of autistic children and developmental functioning of the family of healthy children.[43]

Toubaei et al. showed that the families of depressed people have more satisfaction, physical health, and mental health than families with other psychiatric disorders.[44]

The study by Peyman et al. showed that 23.9% of households have a great tendency to accept their patients at home, 53.8 have a moderate tendency, and 22.3% have no tendency.[45]

Keigobadi et al. showed that the average score of quality of life of caregivers was 4.49 out of 10. Overall, in this study, the quality of life for caregivers was 17% unfavorable, 76.5% somewhat favorable, and 5.9% favorable. From the economic viewpoint, 41.7% were weak, 50% average, and 8.3% good.[46] Noghani et al. showed that the quality of life of these caregivers in all aspects is lower than the others.[42]

Finally, Sharif showed that weak quality of life in women shows the need for more attention to treatment interventions of and social support for promoting well-being and quality of life in this group of caregivers.[47]

As seen from the results of this study, carers of mental patients in Iran have several challenges. Authorities must resolve these challenges with the proper management of caregivers.

Discussion

We conducted this study to examine the challenges of family caregivers of mentally ill patients in Iran. The results indicated that the challenges faced by family caregivers of mentally ill patients in Iran include not meeting the needs of caregivers, burnout and high care burden, high social stigma, low social support of caregivers, and quality of life.

The results of the included studies with others conducted outside Iran show similarities and differences in the needs of family caregivers of these patients in Iran and other countries. Ploeg et al. in Canada concluded that caregivers of PPs need social life, tool support, emotional support, information support, and telephone access to the professional treatment team as well as access to experienced counterparts.[48] Wancata et al. in Austria showed that relieving social isolation is among the components with a high percentage among caregivers' needs, and the fear of labeling and discrimination has the lowest percentage,[49] which is justified by cultural differences. Altruism is considered one of the ancient Persian cultures. Iranians are not indifferent to the family and their neighbors and social view is dominant in Iran. Thus, social isolation has no place in Iran. Another point is that expression of the needs and problems and caring for PPs are under the influence of culture. In Asian countries, unlike European countries, due to issues such as honor, people refrain from expressing these problems and hide them that eventually leads to loss of social support.[50]

In terms of perceived stigma, families of PPs have medium and higher levels of stigma.[30],[31],[51] In the study by Yin et al., majority of family caregivers were hiding the disease of their family members suffering schizophrenia and did not have support of their friends.[52] In the study by Sanden et al., families of patients with social problems had limited their social relationships with friends due to stigma.[53] The study of stigma in patients with mental disorders in Iran and Sweden showed that Iranians, in comparison with Swedish, had fewer stigmas in loneliness that can be due to the Islamic beliefs of the Iranians.[54]

In connection with the burden of caring for PPs, many studies showed that not only in Iran but also in other countries the burden of caring for PPs is significant, and the psychological and mental health of these caregivers have many challenges and they often experience a high percentage of anxiety and depression.[55],[56] In a study on Jamaican Africans, Alexander et al. showed that the burden of family caregiving is moderate in patients with schizophrenia.[57] Caregivers of PPs in Zimbabwe experience significant burden of care,[58] while this is moderate to severe in Iran. Chien showed that in China care burden of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia is high.[59]

Padierna showed a very high burden of care for patients with eating disorders in Spain,[60] but the burden of care for schizophrenic patients in Iran is more than other patients' care burden. The findings of this study show low level of education of family caregivers of patients was associated with an increased burden of care. Zahid and Pahlavanzadeh showed a significant relationship between high level of education and burden of care. It is likely that rising educational levels leads to increased accountability and understanding of the complexity of their patient care.[61],[62] Gafari et al. showed that education is insufficient for informal caregivers' of multiple sclerosis patients.[63]

In the field of social support of family caregivers of PPs, it should be stated that Iranian society is sensitive to the problems of their fellow and has a great desire to overcome them, and people unofficially support these caregivers. However, officially, the Deputy of Department of Medical University nationwide covers acute patients, and welfare organization covers the treatment of chronic PPs, and Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans covers PTSD veterans and their family caregivers. These organizations are mostly responsible for economic and health care support.

Another type of support in Iran is spiritual support. Perception of caregivers of their care responsibility as punishment from God or the feeling that God has abandoned them is associated with higher levels of symptoms of depression, whereas feeling God's presence in the lives and preserving religious beliefs and faith could increase their adaptability by changing caregivers' perception of care burden.[54] In general, religion and spirituality can affect people's adaptability to stressful situations by providing a framework for understanding the meaning and cause of negative events as well as providing a hopeful vision of life. In fact, religious commitment acts as a buffer against stress and moderates negative effects of care on health of caregivers.

Studies in Iran showed that families with PPs have lower quality of life. This finding is consistent with other studies on the significant effects of patient care, especially those with mental disorders. Boyer et al. showed that the selected samples from Chile and France were of poor quality of life.[64] In this regard, Wong et al. concluded that the stress of caring for a relative with a mental illness could reduce their quality of life.[65] Hayes et al. considered the quality of life of caregivers in Australia low as well. Boyer et al. consider the reason of low quality of family life in what these families do today for their patients that was the responsibility of psychiatric centers in the past. Thus, social services available do not supply these changes sufficiently.[64]

Overall, caregivers of patients with mental disorders not only in Iran but also in most countries have many problems and challenges in coping with mental illness. The objective and subjective burnout of family increases in cases where patients with mental disorders are unable to function, are dependent, or have not learned social skills. Thus, family members, especially caregivers, due to using energy and time to provide the care needed, are in danger of reduced quality of life. They experience great emotional stress associated with supporting patient, lack of enjoyable activities, housekeeping problems, feeling of being unwanted, participation in care, uncertain prognosis, and lack of access to social support needed. Nurses can offer training needed such as identifying sources of support, self-efficacy techniques, and empowerment to the family, especially the main caregivers.

A literature review in Iran and this study have some limitations, especially in using standard search terms in national databases that provide the majority of citations in national prevalence studies. To overcome this problem, we used all synonyms of search terms separately in both Persian and English languages. Another major limitation was the lack of good coverage in searching universities research projects and student's thesis.

Conclusion

Results of this study showed that family caregivers of PPs face many challenges in Iran. Uncertainties in meeting the needs of caregivers and the lack of their provision, burnout and high care burden, high social stigma, low social support from caregivers, and low quality of their life were the most important challenges in the literature. Three key elements in relation to these families should never be forgotten: first, every member of society should respect and pay attention to the vital role caregivers play, and this can reduce a lot of stress these caregivers experience. Second, members of professional health team should provide more opportunities to train proper care, support resources in society, and proper communication skills not only for caregivers but also for members of the community by improving interprofessional approach. Third, officials and policymakers can consider the problems and challenges of these caregivers and by adopting appropriate legislation facilitate the path of solving the problems of these caregivers. Therefore, the need for all-inclusive support of family caregivers of patients with mental health problems seems necessary.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgement

This study is derived from a PhD thesis of Nursing sponsored by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors are thankful to the Vice-chancellor for the approval of this research project (code: 395250).

References

- 1.Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual Research Review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:345–65. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadock BJ, Kaplan VA. Kaplan and Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang Y-C, Chou F-C. Effects of Home Visit Intervention on Re-hospitalization Rates in Psychiatric Patients. Community Ment Health J. 2015;5:595–605. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9807-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hengartner MP, Klauser M, Heim G, Passalacqua S, Andreae A, Rössler W, et al. Introduction of a Psychosocial Post Discharge Intervention Program Aimed at Reducing Psychiatric Rehospitalization Rates and at Improving Mental Health and Functioning. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;5:25–34. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awad AG, Voruganti LNP. The Burden of Schizophrenia on Caregivers. PharmacoEconomics. 2012;26:149–62. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haresabadi M, Bibak B, Bayati H, Akbari M. Assessing burden of family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia Admitted in IMAM REZA hospital. Bojnurd J Med Univ North Khorasan. 2013;4:165–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navidian A, Salar AR, Hashemi Nia A, A K. Study of mental exhaustion experienced by family caregivers of patients with mental disorders, Zahedan Psychiatric Hospital. J Babol Uni Med Sci. 2001;3:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker ET, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Almeida DM. Daily stress and cortisol patterns in parents of adult children with a serious mental illness. Health Psychol. 2012;31:130–8. doi: 10.1037/a0025325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zendjidjian X, Richieri R, Adida M, Limousin S, Gaubert N, Parola N, et al. Quality of life among caregivers of individuals with affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:660–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lillis C, LeMone P, LeBon M, Lynn P. Study guide for fundamentals of nursing: The art and science of nursing care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Möller-Leimkühler AM, Wiesheu A. Caregiver burden in chronic mental illness: The role of patient and caregiver characteristics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262:157–66. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson P, Trauer T, Kelly B, O'Connor M, Thomas K, Summers M, et al. Reducing the psychological distress of family caregivers of home-based palliative care patients: Short-term effects from a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1987–93. doi: 10.1002/pon.3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid-Büchi S, Halfens RJ, Dassen T, van den Borne B. Psychosocial problems and needs of posttreatment patients with breast cancer and their relatives. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friðriksdóttir N, Sævarsdóttir Þ, Halfdánardóttir SÍ, Jónsdóttir A, Magnúsdóttir H, Ólafsdóttir KL, et al. Family members of cancer patients: Needs, quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:252–8. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.529821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coughlan M, Cronin P. Doing a literature review in nursing, health and social care. 2 edition. London: Sage; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shamsaee, Mohammadkhan, Vanaki Needs of family caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. J Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. 2011;17:57–63. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shamsaei F, Cheraghi F, Esmaeilli R. The Family Challenge of Caring for the Chronically Mentally Ill: A Phenomenological Study. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9:18–26. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeinalian P, Mottaghipour Y, Samimi M. Validity and the cultural adaptation of the carers'needs assessment for schizophrenia and assessing the needs of family members of bipolar mood disorder and schizophrenia spectrum patients. J Ment Health Principles. 2011;12:684–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behpagoh A, Mahmodi M. Need Assessment for Social Support in Mothers of Children with Autism. J Psychol growth. 2016;11:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chimeh N, Malakoti S, Panaghi L, Ahmad Abadi Z, Nojomi M, Ahmadi Tonkaboni A. Care giver burden and mental health in schizophrenia. J Fam Res. 2008;4:277–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharifi M, Fatehizade M. The effectiveness of group problem-solving training on burnout in women caregivers of family patient member in Falavarjan, Isfahan, IR Iran. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2013;14:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saleh S, Zahedi Asl M. Correlation of Social Support with Social Health of Psychiatry Veterans Wives. Iran J War Public Health. 2014;6:201–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdollahpour I, Noroozian M, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. Caregiver burden and its determinants among the family members of patients with dementia in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:544–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navidian A, Bahari F. Burden experienced by family caregivers of patients with mental disorders. Pak J Psychol Res. 2008;23:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamsaei F, Cheraghi F, Bashirian S. Burden on Family Caregivers Caring for Patients with Schizophrenia. Iran J Psychiatry. 2015;10:239–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosseini S, Sheykhmounesi F, Shahmohammadi S. Evaluation of mental health status in caregivers of patients with chronic psychiatric disorders. Pakistan journal of biological sciences. 2010;13:325–9. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.325.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaghee S, Salarhaji A. Stigma in family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia hospitalized in ibn-sina psychiatric hospital of mashhad in 2014-2015. J Torbat Heydariyeh Uni Med Sci. 2015;3:10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamsaee F, Mohammadkhan S, Vanaki Z. Meaning of Health from the perspective of family caregivers Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Qualitative Study. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2013;1:52–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadeghi M, Kaviani H, Rezaee R. Comparison of the stigma of mental illness in families of patients with depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Cogn Sci News. 2004;5:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahveisi B, Shoja S, Fadaee F, Dolatshahi B. Compare the stigma of mental illness in families of patients with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder without a psychiatric traits. J Rehab Ment Disord. 2008;8:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beirami M, Andalib M, Poresmaeel A, Mohammadibakhsh L. Comparison of perceived social support and religiosity in PTSD patients, Their wives and control group. J Med Sci. 2014;17:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mami S, kaikhavani S, amirian K, neyazi E. The effectiveness of family psychoeducation (Atkinson and coia model) on mental health family members of patients with psychosis. Scientific Journal of Ilam University of Medical Sciences. 2016;24:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheikholeslami F, Khalatbary J, Ghorbanshiroudi S. Effectiveness of Stress Coping Skills Training With Psycho-Educational Approach among Caregiversof Schizophrenic Patients on Family Function And Psychological Wellbeing. Holistic Nurs Midwif J. 2016;26:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karamlou S, Mazaheri A, Mottaghipour Y. Effectiveness of family psycho-education program on family environment improvement of severe mental disorder patients. Int J Behav Sci. 2010;4:123–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharif F, Shaygan M, Mani A. Effect of a psycho-educational intervention for family members on caregiver burdens and psychiatric symptoms in patients with schizophrenia in Shiraz, Iran. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:48–57. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pahlavanzadeh S, Navidian A, Yazdani M. The effect of psycho-education on depression, anxiety and stress in family caregivers of patients with mental disorders. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2010;14:228–36. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mottaghipour Y, Woodland L, Bickerton A, Sara G. Working with families of patients within an adult mental health service: Development of a programme model. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14:267–71. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koolaee AK, Etemadi A. The outcome of family interventions for the mothers of schizophrenia patients in Iran. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56:634–46. doi: 10.1177/0020764009344144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omranifard V, Esmailinejad Y, Maracy MR, Jazi AHD. The Effects of Modified Family Psychoeducation on the Relative's Quality of Life and Family Burden in Patients with Bipolar Type I Disorder. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2009;27:100–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharifi M, Fatehizade M. The relationship between religious coping with depression and burnout in in family caregivers. Modern Care. J Sch Nurs Mid Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2012;9:327–35. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muralidharan A, Lucksted A, Medoff D, Fang LJ, Dixon L. Stigma: A Unique Source of Distress for Family Members of Individuals with Mental Illness. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43:484–93. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9437-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aali S, Amin A, Abdekhodaee M, Ghanaee A, Moharrari F. Function of families with children with autism spectrum disorders compared to Families with children healthy. Med J Mashhad Uni Med Sci. 2015;1:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toubaei S, Mani A. Life satisfaction and mental health in depressed patients' families. Int J Behav Sci. 2010;4:177–82. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peyman N, Bahrami M, Yousef S, Vahedian M. Investigating the problems and the family willing to accept and care of mental patient: At home after discharge from the hospital Psychiatric city of Mashhad. Qua J Fund Ment Health. 2005;25:63–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keighobadi S, Neishabouri M, Haghighi N, Sadeghi T. Assessment of Quality of life in Caregivers of Patients with Mental Disorder in Fatemie hospitals of Semnan city. Adv Nurs Mid. 2013;22:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharif Ghaziani Z, Ebadollahi Chanzanegh H, Fallahi Kheshtmasjedi M, Baghaie M. Quality of Life and Its Associated Factors among Mental Patients Families. J Health Care. 2015;17:166–77. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ploeg J, Biehler L, Willison K, Hutchison B, Blythe J. Perceived support needs of family caregivers and implications for a telephone support service. Can J Nurs Res Arch. 2016;33:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wancata J, Krautgartner M, Berner J, Scumaci S, Freidl M, Alexandrowicz R, et al. The Carers' needs assessment for Schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:221–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan SW. Global perspective of burden of family caregivers for persons with schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2011;25:339–49. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin Y, Zhang W, Hu Z, Jia F, Li Y, Xu H, et al. Experiences of stigma and discrimination among caregivers of persons with schizophrenia in China: A Field Survey. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Sanden RL, Bos AE, Stutterheim SE, Pryor JB, Kok G. Experiences of stigma by association among family members of people with mental illness. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:73–85. doi: 10.1037/a0031752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobsson L, Ghanean H. Internalized stigma of mental illness in Sweden and Iran–A comparative study. Open J Psychiatr. 2013;3:370–4. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogilvie AD, Morant N, Goodwin GM. The burden on informal caregivers of people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steele A, Maruyama N, Galynker I. Psychiatric symptoms in caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: A review. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander G, Bebee C-E, Chen K-M, Vignes R-MD, Dixon B, Escoffery R, et al. Burden of caregivers of adult patients with schizophrenia in a predominantly African ancestry population. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marimbe BD, Kajawu L, Muchirahondo F, Marimbe BD, Cowan F, Lund C. Perceived burden of care and reported coping strategies and needs for family caregivers of people with mental disorders in Zimbabwe: Original research. Africa J Disabil. 2016;5:1–9. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v5i1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chien WT, Chan SW, Morrissey J. The perceived burden among Chinese family caregivers of people with schizophrenia. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1151–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Padierna A, Martín J, Aguirre U, González N, Muñoz P, Quintana JM. Burden of caregiving amongst family caregivers of patients with eating disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2013;48:151–61. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zahid MA, Ohaeri JU. Relationship of family caregiver burden with quality of care and psychopathology in a sample of Arab subjects with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:71–80. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pahlavanzadeh S, Dalvi-Isfahani F, Alimohammadi N, Chitsaz A. The effect of group psycho-education program on the burden of family caregivers with multiple sclerosis patients in Isfahan in 2013-2014. Iranian J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20:420–5. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.161000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gafari S, Khoshknab MF, Nourozi K, Mohamadi E. Informal caregivers' experiences of caring of multiple sclerosis patients: A qualitative study. Iranian J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2017;22:243–9. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.208168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyer L, Caqueo-Urízar A, Richieri R, Lancon C, Gutiérrez-Maldonado J, Auquier P. Quality of life among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: A cross-cultural comparison of Chilean and French families. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:42–50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong DFK, Lam AYK, Chan SK, Chan SF. Quality of life of caregivers with relatives suffering from mental illness in Hong Kong: Roles of caregiver characteristics, caregiving burdens, and satisfaction with psychiatric services. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:15–23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hayes L, Hawthorne G, Farhall J, O'Hanlon B, Harvey C. Quality of life and social isolation among caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: Policy and outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:591–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]