Abstract

Background:

There was still conflict on the antithrombotic advantage of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel among East Asian population with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). We considered that the baseline bleeding risk might be an undetected key factor that significantly affected the efficacy of ticagrelor.

Methods:

A total of 20,816 serial patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) from October 2011 to August 2014 in the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region were enrolled in the present study. Patients receiving ticagrelor or clopidogrel were further subdivided according to basic bleeding risk. The primary outcome was net adverse clinical events (NACEs) defined as major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (MACCE, including all-cause death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, or stroke) and any bleeding during 1-year follow-up. Comparison between ticagrelor and clopidogrel was adjusted by propensity score matching (PSM).

Results:

Among the 20,816 eligible PCI patients who were included in this study, there were 1578 and 779 patients in the clopidogrel and ticagrelor groups, respectively, after PSM, their clinical parameters were well matched. Patients receiving ticagrelor showed comparable NACE risk compared with those treated by clopidogrel (5.3% vs. 5.1%, P = 0.842). Furthermore, ticagrelor might reduce the MACCE risk in patients with low bleeding risk but increase MACCE in patients with moderate-to-high bleeding potential (ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel, low bleeding risk: 2.5% vs. 4.9%, P = 0.022; moderate-to-high bleeding risk: 4.8% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.225; interaction P = 0.021), with vast differences in all bleeding (low bleeding risk: 1.5% vs. 0.8%, P = 0.210; moderate-to-high bleeding risk: 4.8% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.002; interaction P = 0.296).

Conclusion:

Among real-world Chinese patients with ACS treated by PCI, ticagrelor only showed superior efficacy in patients with low bleeding risk but lost its advantage in patients with moderate-to-high bleeding potential.

Keywords: Baseline Bleeding Risk, Clopidogrel, Crusade Score, Efficacy, Ticagrelor

摘要

背景:

ACS患者中,替格瑞洛对比氯吡格雷在抗血栓方面的优势仍存在争议。我们认为基线出血风险可能是一个未被发现的 关键因素,显著影响替格瑞洛的疗效。

方法:

本研究连续纳入我中心2011年10月至2014年8月期间接受经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(PCI)的20816例患者。根据CRUSADE 评分,将接受替格瑞洛或氯吡格雷治疗的患者进一步细分为低和中至高等出血风险组。主要研究终点定义为1年随访期内的 净临床不良事件(NACE),由主要心脑血管不良事件(MACCE,包括全因死亡,心肌梗死,缺血驱动的靶血管血运重建 或脑卒中组成)和全部出血组成。替格瑞洛与氯吡格雷之间的比较通过倾向评分匹配(PSM)按照1:2的比例进行匹配校正。

结果:

本研究共纳入20,816例PCI患者, 经PSM校正后, 氯吡格雷组和替格瑞洛组分别有1578例和779 例患者被纳入分析,临床基线指标匹配良好。接受替格瑞洛治疗的患者与氯吡格雷治疗组相比NACE风险相当 (5.3% 比 5.1%,P = 0.842),MACCE发生率数值上有所降低(3.1%比4.0%,P = 0.246),全部出血显著增加 (2.3%vs 1.0%,P = 0.015)。在不同出血风险人群的分析中,发现对于基础出血风险低的患者,替格瑞洛可以明显 降低MACCE风险,但在出血中-高危的患者中,替格瑞洛组MACCE发生率反而有所增加(替格瑞洛与氯吡格雷,低 危:2.5% 比 4.9%,P = 0.022; 中-高危:4.8% 比 3.0%,P = 0.225; 相互作用P = 0.021),全部出血的比较结果在两类人群中也 有较大差异(替格瑞洛与氯吡格雷,低危:1.5%比0.8%,P = 0.210;中-高危:4.8%比3.0%,P = 0.002; 相互作用P = 0.296)。

结论:

在中国的ACS患者中,与氯吡格雷相比,替格瑞洛仅在出血风险较低的患者中表现出显著的抗栓优势,而在出血中-高 危患者中却并不优于氯吡格雷。

INTRODUCTION

Ticagrelor was strongly recommended for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS),[1,2] mainly according to the results of the PLATO trial.[3,4] Consistent results were also reported in real-world studies such as the PRACTICAL study from the SWEDEHEART registry.[5] However, there was also conflicting evidence on the efficacy of ticagrelor among the East Asian population with ACS. The PHILO study[6] recruited 817 East Asian patients with ACS and found no improvement; however, a numerical increase in ischemic risk (using a definition that is consistent with PLATO) in patients receiving ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel. The most recent meta-analysis,[7] which focused on the population of East Asia, also demonstrated no advantage of ticagrelor on antithrombotic efficiency. Whereas, two recent real-world studies reported that ticagrelor could provide a marginally or significantly favorable antithrombotic efficacy in patients with ACS[8] or acute myocardial infarction (AMI),[9] both with similar major bleeding rates compared with clopidogrel. These contradictory results have caused considerable confusion regarding the efficacy of ticagrelor, providing the impetus to formulate better antiplatelet strategies.

Bleeding is an independent risk factor for ischemic events.[10,11] There is concern that compared with Western patients, East Asian patients suffer more bleeding with the “standard” antiplatelet therapy, which was also called the “East Asian paradox.”[12] In the PLATO trial, the increases in non-CABG-related major bleeding was approximately 170% versus 19% among East Asian patients versus the whole population.[3,13] Another real-world study from China also showed that bleeding could be lowered by approximately 40% after switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel.[14] Therefore, the potential bleeding risk of East Asian patients might be closely related to the efficacy of ticagrelor, and the risk greatly changed when ticagrelor was applied from Phase III randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to the real-world clinical practice. However, the impact of baseline bleeding risk on the efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel has never been reported in the East Asian population.

The present study was a single-center, large-sample, pragmatic clinical trial, which divided the ACS patients by low- and moderate-to-high baseline bleeding risk according to the CRUSADE score.[15] We aim to clarify the influence of baseline bleeding risk on the efficacy advantage of ticagrelor and to provide more evidence for the optimal use of ticagrelor in the East Asian population.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region. Since the present study was a post hoc analysis of exist data, there was no informed consent.

Study population and design

Utilizing information in the preregistered database, a total of 20,816 serial ACS patients from October 2011 to August 2014 in the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region were enrolled in the present study. There were no special exclusion criteria. Patients were divided into two groups based on drug administration at discharge. The baseline bleeding risk was judged according to the CRUSADE score and was categorized into low bleeding risk (which contain CRUSADE risk levels from extremely low-to-low) and moderate-to-high bleeding risk (which contain CRUSADE risk levels from moderate to extremely high). Comparisons between ticagrelor and clopidogrel, as well as the subgroup analysis of different bleeding risk, were both adjusted by the propensity score matching (PSM).

Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcome was net adverse clinical events (NACEs) defined as major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (MACCE, a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, or stroke) and any bleeding as defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition (Grades 1–5)[16] during 1-year follow up. Major secondary end-points were MACCE and any bleeding at 1 year. CRUSADE levels were defined as extremely low, low, moderate, high, and extremely high, corresponding to the CRUSADE score ranges of 1–20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–91, respectively.[15]

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages and compared using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Continuous data are summarized by the means and standard deviations, and the data were compared using an independent t-test. PSM was performed to minimize the differences in the baseline characteristics between the treatments of ticagrelor and clopidogrel. Unbalanced baseline factors were adjusted using multivariate logistic regression analysis, conditional on covariates such as sex, smoking status, ACS spectrum, previous ischemic stroke, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min, use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI), and the presence of multivessel disease. The PSM was used to match patients administered ticagrelor and those given clopidogrel in a 1:2 ratio. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the study population

A total of 20,816 patients with ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were included in this study, with 779 patients in the group treated with ticagrelor. The clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor was more likely to be administered in patients with poorer medical history, such as smoking (57.3% vs. 47.8%, P < 0.001) and prior stroke (8.9% vs. 6.9%, P = 0.034), and ACS categories of higher risk, such as ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (30.3% vs. 18.0%, P < 0.001) or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (12.2% vs. 8.8%, P = 0.001). Patients assigned to ticagrelor treatment seem to have better profiles of renal function (eGFR: 124.38 ± 36.04 vs. 102.08 ± 34.23 ml/min, P < 0.001; eGFR <60 ml/min: 2.4% vs. 6.0%, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population before and after PSM

| Characteristics | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 779) | Clopidogrel (n = 20,037) | Statistical values | P | Ticagrelor (n = 779) | Clopidogrel (n = 1558) | Statistical values | P | |

| Female, n (%) | 225 (28.9) | 5961 (29.7) | 0.270* | 0.604 | 225 (28.9) | 441 (28.3) | 0.085 | 0.771 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 60.54 ± 10.53 | 61.30 ± 10.64 | 1.951† | 0.051 | 60.54 ± 10.53 | 60.97 ± 10.54 | 0.918 | 0.359 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||||||

| Current smoker | 446 (57.3) | 9578 (47.8) | 26.829* | <0.001 | 446 (57.3) | 900 (57.8) | 0.056 | 0.813 |

| Hypertension | 451 (57.9) | 11,398 (56.9) | 0.312* | 0.576 | 451 (57.9) | 849 (54.5) | 2.435 | 0.119 |

| Diabetes | 192 (24.6) | 4734 (23.6) | 0.432* | 0.463 | 192 (24.6) | 371 (23.8) | 0.198 | 0.657 |

| Prior, n (%) | ||||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 121 (15.5) | 3535 (17.6) | 2.305* | 0.129 | 121 (15.5) | 269 (17.3) | 1.122 | 0.290 |

| Stroke | 69 (8.9) | 1380 (6.9) | 4.494* | 0.034 | 69 (8.9) | 130 (8.3) | 0.176 | 0.675 |

| ACS categories, n (%) | ||||||||

| Unstable angina | 448 (57.5) | 14,657 (73.1) | 92.132* | <0.001 | 448 (57.5) | 896 (57.5) | <0.001 | 1.000 |

| NSTEMI | 95 (12.2) | 1767 (8.8) | 10.496* | 0.001 | 95 (12.2) | 194 (12.5) | 0.032 | 0.859 |

| STEMI | 236 (30.3) | 3613 (18.0) | 74.826* | <0.001 | 236 (30.3) | 468 (30.0) | 0.016 | 0.899 |

| eGFR, mean ± SD | 124.38 ± 36.04 | 102.08 ± 34.23 | −17.512† | <0.001 | 124.38 ± 36.04 | 104.78 ± 32.90 | −12.552 | <0.001 |

| <60 ml/min, n (%) | 19 (2.4) | 1207 (6.0) | 17.385* | <0.001 | 19 (2.4) | 38 (2.4) | <0.001 | 1.000 |

| Platelet, mean ± SD | 213.03 ± 54.00 | 205.75 ± 51.58 | −3.799† | <0.001 | 213.03 ± 54.00 | 204.84 ± 50.69 | −3.475 | 0.001 |

| <100 × 109/L, n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 118 (0.6) | – | 0.809 | 5 (0.6) | 8 (0.5) | – | 0.770 |

| Hemoglobin, mean ± SD | 139.90 ± 16.56 | 138.30 ± 15.79 | −2.735† | 0.006 | 139.90 ± 16.56 | 139.11 ± 15.05 | −1.109 | 0.267 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 46 (5.9) | 1175 (5.9) | 0.002* | 0.962 | 46 (5.9) | 85 (5.5) | 0.198 | 0.656 |

| Medications before PCI, n (%) | ||||||||

| Aspirin | 776 (99.6) | 19559 (97.6) | 13.294* | <0.001 | 776 (99.6) | 1534 (98.5) | 6.070 | 0.014 |

| Loading dose regimen | 698 (89.6) | 18263 (91.1) | 2.203* | 0.138 | 698 (89.6) | 1442 (92.6) | 5.865 | 0.015 |

| GPI use, n (%) | 273 (35.0) | 4794 (23.9) | 50.340* | <0.001 | 273 (35.0) | 543 (34.9) | 0.008 | 0.927 |

| Radial access, n (%) | 744 (95.5) | 18,005 (89.5) | 26.748* | <0.001 | 744 (95.5) | 1492 (95.8) | 0.083 | 0.774 |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 476 (61.1) | 10,829 (54.0) | 15.057* | <0.001 | 476 (61.1) | 956 (61.4) | 0.014 | 0.904 |

| RVD (mm), mean ± SD | 3.00 ± 0.37 | 2.99 ± 0.36 | 0.651† | 0.515 | 3.00 ± 0.37 | 2.95 ± 0.45 | 0.612 | 0.618 |

| Other medication, n (%) | ||||||||

| Statins | 749 (96.1) | 17,008 (84.9) | 75.920* | <0.001 | 749 (96.1) | 1502 (96.4) | 0.756 | 0.756 |

| β-blocker | 588 (75.5) | 15,916 (79.4) | 7.130* | 0.008 | 588 (75.5) | 1174 (75.4) | 0.005 | 0.946 |

*χ2 values; -: Fisher exact test; †t values. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <120 g/L for men or <11 g/L for women. PSM: Propensity score matching; ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI: ST elevation myocardial infarction; SD: Standard deviation; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; PCI: Percutaneous coronary inervention; GPI: Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; RVD: Reference vessel diameter.

We found that GPI was more frequently used in patients with ticagrelor (35.0% vs. 23.9%, P < 0.001), which was complicated with a higher incidence of multivessel disease (61.1% vs. 54.0%, P < 0.001). Nonetheless, the number of stents, along with the reference vessel diameter, were both comparable between the two groups. Radial access was more commonly applied in ticagrelor-treated patients (95.5% vs. 85.5%, P < 0.001). For other medications in the ticagrelor group, more patients received statins (96.1% vs. 84.9%, P < 0.001), while a fewer were treated with β-blockers (75.5% vs. 79.4%, P = 0.008).

There were 1578 and 779 patients in the clopidogrel and ticagrelor groups after PSM, respectively, and the clinical characteristics were well matched, with the exception of a higher level of eGFR in the ticagrelor group. However, the proportion of patients with an eGFR below 60 ml/min was comparable after PSM between the two groups. Although there was a significant difference in aspirin use and the loading dose, both were comparable between the two treatment groups.

One-year clinical outcomes in patients treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel

As shown in Table 2, among the unmatched population, the primary end-point of NACE was higher in patients in the ticagrelor group (5.3% vs. 4.1%, P = 0.116). Ticagrelor treatment did not significantly influence the risk of the composite endpoints of MACCE (ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel: 3.1% vs. 3.2%, P = 0.842) or its individual components (P > 0.05). Whereas ticagrelor significantly increased major bleeding risk defined as BARC3–5 (0.8% vs. 0.3%, P = 0.037), as well as BARC2–5 (1.0% vs. 0.4%, P = 1.022) and all bleeding (2.3% vs. 1.0%, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

The 1-year clinical outcomes of the study population before and after PSM, n (%)

| Outcomes | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 779) | Clopidogrel (n = 20,037) | χ2 values | P | Ticagrelor (n = 779) | Clopidogrel (n = 1558) | χ2 values | P | |

| NACE | 41 (5.3) | 825 (4.1) | 2.469 | 0.116 | 41 (5.3) | 79 (5.1) | 0.040 | 0.842 |

| MACCE | 24 (3.1) | 643 (3.2) | 0.040 | 0.842 | 24 (3.1) | 63 (4.0) | 1.343 | 0.246 |

| Death | 7 (0.9) | 242 (1.2) | 0.606 | 0.436 | 7 (0.9) | 19 (1.2) | 0.486 | 0.486 |

| MI | 5 (0.6) | 92 (0.5) | 0.540 | 0.463 | 5 (0.6) | 15 (1.0) | 0.630 | 0.427 |

| Stroke | 1 (0.1) | 30 (0.1) | – | 1.000 | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | – | 0.670 |

| TVR | 13 (1.7) | 325 (1.6) | 0.010 | 0.919 | 13 (1.7) | 29 (1.9) | 0.109 | 0.741 |

| All bleeding | 18 (2.3) | 195 (1.0) | 13.244 | <0.001 | 18 (2.3) | 16 (1.0) | 5.969 | 0.015 |

| BARC2–5 | 8 (1.0) | 84 (0.4) | – | 0.022 | 8 (1.0) | 6 (0.4) | – | 0.084 |

| BARC3–5 | 6 (0.8) | 60 (0.3) | – | 0.037 | 6 (0.8) | 3 (0.2) | – | 0.068 |

–: Fisher exact test. PSM: Propensity score matching; NACE: Net adverse clinical event; MACCE: Major adverse cardiac or cerebral events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium.

Different from the results in the unmatched population, the incidence of NACE was comparable in the groups treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel after PSM (5.3% vs. 5.1%, P = 0.842). Reductions in the occurrence of MACCE were found in matched patients in the ticagrelor group versus the clopidogrel group (3.1% vs. 4.0%, P = 0.246), mainly due to different degrees of decline in each end-point of ischemia. The safety profile of ticagrelor in comparison to clopidogrel remained after PSM not only for all bleeding (2.3% vs. 1.0%, P = 0.015) but also for the higher trend of bleeding that requires medical therapy (BARC2–5, 1.0% vs. 0.4%, P = 0.084) and for major bleeding (BARC3–5, 0.8% vs. 0.2%, P = 0.068).

Impact of CRUSADE bleeding risk on clinical outcomes of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel adjusted by propensity score matching

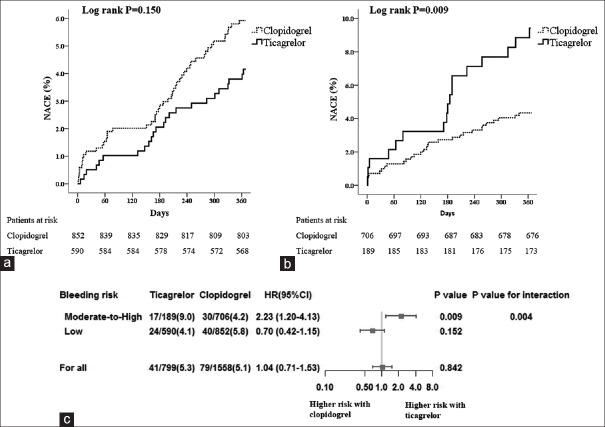

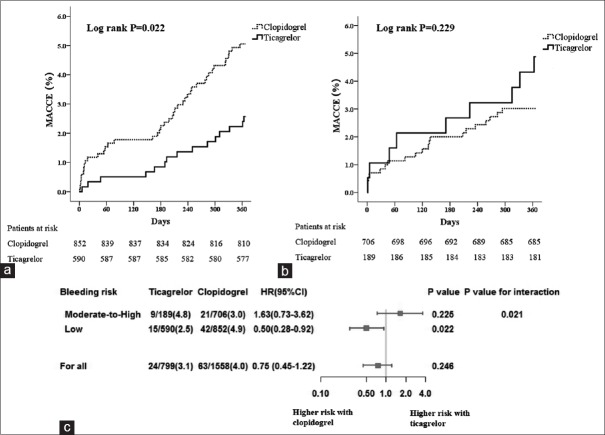

Surprising outcomes were found on the efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel between patients with low- and moderate-to-high baseline bleeding risk. After PSM, there were 1578 patients treated with clopidogrel matched to the 779 patients treated with ticagrelor (2:1). We first noticed that ticagrelor was less frequently administered in patients with low bleeding potential (189/779, 24.3%) whereas the use of clopidogrel accounted for nearly half (706/1578, 44.7%). As demonstrated in Table 3, although with no significance, ticagrelor was found to reduce the number of NACE in patients with a CRUSADE score below 30 (4.1% vs. 5.8%, P = 0.152); however, ticagrelor markedly increased the incidence of NACE in those patients with a CRUSADE score above 30 (9.0% vs. 4.2%, P = 0.009). Our results showed that among patients with low bleeding risk, ticagrelor obviously reduced MACCE risk (2.5% vs. 4.9%, P = 0.022). Meanwhile, ticagrelor only slightly increased all bleeding, as well as bleeding with BARC2o reduce, with no statistical significance (P > 0.05). However, in patients of moderate-to-high bleeding risk, ticagrelor not only does not reduce the risk of MACCE but also causes an increase in the occurrence of MACCE (4.8% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.225), with an extreme increase in all bleeding (4.8% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.006) and bleeding of BARC2–5 (3.2% vs. 0.7%, P = 0.015) and BARC3–5 (2.1% vs. 0.4%, P = 0.040). Time-to-event curves for the first occurrence of NACE, MACCE, and bleeding outcomes in the subgroups of patients with low- and moderate-to-high bleeding risk during the 1-year follow-up period are shown in Figures 1–3 with an interaction analysis.

Table 3.

Impact of CRUSADE bleeding risk on clinical outcome of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel adjusted by PSM, n (%)

| Outcomes | Moderate-to-high bleeding risk | Low bleeding risk | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 189) | Clopidogrel (n = 706) | χ2 values | P | Ticagrelor (n = 590) | Clopidogrel (n = 852) | χ2 values | P | |

| NACE | 17 (9.0) | 30 (4.2) | 6.748 | 0.009 | 24 (4.1) | 49 (5.8) | 2.055 | 0.152 |

| MACCE | 9 (4.8) | 21 (3.0) | 1.470 | 0.225 | 15 (2.5) | 42 (4.9) | 5.233 | 0.022 |

| Death | 3 (1.6) | 8 (1.1) | – | 0.708 | 4 (0.7) | 11 (1.3) | 1.273 | 0.259 |

| MI | 1 (0.5) | 8 (1.1) | – | 0.693 | 4 (0.7) | 7 (0.8) | – | 1.000 |

| Stroke | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | – | 0.378 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | – | 0.274 |

| TVR | 4 (2.1) | 6 (0.8) | – | 0.232 | 9 (1.5) | 23 (2.7) | 2.215 | 0.137 |

| All bleeding | 9 (4.8) | 9 (1.3) | – | 0.006 | 9 (1.5) | 7 (0.8) | 1.574 | 0.210 |

| BARC2-5 | 6 (3.2) | 5 (0.7) | – | 0.015 | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | – | 0.571 |

| BARC3-5 | 4 (2.1) | 3 (0.4) | – | 0.040 | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0.167 |

–: Fisher exact test. PSM: Propensity score matching; NACE: Net adverse clinical event; MACCE: Major adverse cardiac or cerebral events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium.

Figure 1.

Impact of bleeding risk on NACE among patients receiving ticagrelor versus clopidogrel. (a and b) Time-to-event curves for the NACE through 1-year follow-up in patients with low (a) or moderate-to-high bleeding risk (b); (c) Subgroup analysis on the net efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with different bleeding risk. NACE: Net adverse clinical event.

Figure 3.

Impact of bleeding risk on all bleeding among patients receiving ticagrelor versus clopidogrel. (a and b) Time-to-event curves for the all bleeding through 1-year follow-up in patients with low (a) or moderate-to-high bleeding risk (b); (c) Subgroup analysis on the safety of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with different bleeding risk.

Figure 2.

Impact of bleeding risk on MACCE among patients receiving ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel. (a and b) Time-to-event curves for the MACCE through 1-year follow-up in patients with low (a) or moderate-to-high bleeding risk (b); (c) Subgroup analysis on the ischemic efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with different bleeding risk. MACCE: Major adverse cardiac or cerebral events.

DISCUSSION

The current study observed the efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel among real-world Chinese patients with ACS undergoing PCI and the subgroups of patients with different baseline bleeding risks according to the CRUSADE score. We found that compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor brought no antithrombotic benefit in the whole ACS population or in those with moderate-to-high baseline bleeding risk but markedly reduced the ischemic events in patients with low baseline bleeding risk. The baseline bleeding potential obviously affected the efficacy of ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel.

Unlike in Western countries, evidence for the efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel was conflicting in the population of East Asia. A randomized trial[6] and meta-analysis[7] demonstrated that ticagrelor was no longer superior over clopidogrel in efficiency, with increased major bleeding. Whereas, two observational studies reported that ticagrelor offered significantly or marginally better anti-ischemic protection than clopidogrel in ACS[8] or AMI[9] patients, both without an increase in the rate of major bleeding. The above evidence implied that some critical factor might be closely involved in the efficacy of ticagrelor, which was special in East Asian patients and was changed when ticagrelor was applied from Phase III RCTs to the real-world clinical practice.

Different from clopidogrel, ticagrelor retained its potent platelet inhibition in the East Asian population with no resistance phenomenon reported. Our previous PK/PD trial[17] found that even among patients with an eGFR below 60 ml/min, ticagrelor could inhibit platelet aggregation by 80% (30 patients in the ticagrelor group, all from China mainland). Therefore, the conflicting advantages of ticagrelor were unlikely due to the difference in antiplatelet activity. Substantial evidence has demonstrated that East Asian patients were much more susceptible to bleeding under antiplatelet therapy. It was reported that following the same does of ticagrelor, the degree of platelet inhibition was obviously higher in East Asian patients compared Caucasian.[18] What is worse, even on the same level of on-treatment platelet reactivity, East Asian patients were also more likely to have bleeding events.[19] There is no doubt that bleeding was closely related to the occurrence of ischemic events, directly or indirectly.[10,11] Therefore, it might be the potential bleeding risk responsible for the conflicting results between Western and East Asia, as well as between RCTs and real-world studies among East Asian patients. However, few studies have focused on the impact of baseline bleeding risk on the efficacy of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel.

The present real-world study in mainland China found that the antithrombotic efficiency of ticagrelor was similar in comparison to clopidogrel in the whole ACS population, with an obvious or marginal increase in overall bleeding and major bleeding. We then further divided the patients into low- and moderate-to-high bleeding risk according to the CRUSADE score. First, we noticed that ticagrelor was more frequently administered in patients with low bleeding risk (75.7%), reflecting general concerns about the bleeding risk of ticagrelor and obvious selection bias for patients with low bleeding potential in the real-world clinical practice. We then surprisingly found that when compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor was markedly superior in reducing MACCE in patients with low bleeding risk, with comparable major bleeding and slightly higher overall bleeding, which were quite similar with the results of the two observational studies in Taiwan, China.[8,9] What should also be mentioned is that even in the PRACTICAL study, bleeding that required admission was significantly 20% higher in the ticagrelor group. Hence, if there is no selective bias, East Asians who are more likely to have bleeding may not be the same or even have less major bleeding when using ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel.

Our results also showed that ticagrelor was associated with a worse occurrence of MACCE among patients with moderate-to-high bleeding risk, implying that a high baseline bleeding risk might attenuate the efficacy of ticagrelor in real-world patients of East Asia. What could also be shown is that the results of this subgroup were the primary reason for the comparable efficacy outcomes of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in the whole ACS population. We believe that this finding might also be valuable to explain the outcomes of RCTs from East Asia, because, in an RCT, patients at moderate-to-high bleeding risk could not be excluded from the ticagrelor arm, as long as the general inclusion/exclusion criteria were met.

We noticed that in the following versions of ESC or ACC guidelines, ticagrelor was strongly recommended over clopidogrel in NSTE-ACS patients at moderate-to-high risk of ischemic events and in STEMI patients, as long as there is no contradiction.[1,2] Correspondingly, our results demonstrated that there should be more consideration of the bleeding potentiality, in addition to ischemic risk, when judging whether ticagrelor was superior in an individual patient from East Asia. Just as the DAPT score is used to guide whether to extend the duration of dual-antibiotic therapy,[20] the SYNTAX score II is used to assist in determining the method of revascularization;[21] perhaps for the East Asian population, there should also be an assessment method that combines ischemia and hemorrhage. More clinical trials focusing on a selection of P2Y12 antagonist and duration of the double antiplatelet therapy are still needed to provide critical evidence supporting the decision of optimal antiplatelet regimens, especially among East Asia patients with both high risks at ischemic and bleeding events.

Limitation

First, although ticagrelor was recommended in patients with STEMI, or with NSTE-ACS at moderate-to-high risk of ischemic events,[1,2] patients at low risk of ischemic events might be included in this study because of its nature of real-world study and without specific exclusion criteria. Therefore, the efficacy of ticagrelor might be underestimated. Second, the sample size was reduced after PSM, which leads to the loss of statistical significance in some bleeding results while the data remained unchanged. Third, the present study was observational; although PSM was performed, there might be some potential prognostic factors not included in the database and the matching. In addition, since prasugrel is not available in China, only ticagrelor and clopidogrel were observed in the present study. In addition, high combination rate of GPI (35% after PSM) was observed in the present study. Although we found no interaction impact of GPI on the bleeding outcomes of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel (P = 0.307 for interaction; data not shown), the “bail-out” use of GPI should be more highlighted in the real-world clinical practice. Finally, the study data were also inevitable on selection and (or) treatment bias, as well as underestimated event rate. Temporary discontinuation or switching of ticagrelor because of slight or mild bleeding (BARC1–2) might not be completely recorded in the current observational study, which might partially explain why we failed to discover a direct causation between hemorrhage and ischemic events in the subgroup of moderate-to-high bleeding risk in the current database (data not shown), which should be further confirmed in the further trials.

In conclusion, among real-world Chinese patients with ACS treated by PCI, the MACCE rate in the ticagrelor group was numerically lower than that in the clopidogrel group and affected by the baseline bleeding risk of patients. Ticagrelor showed superior efficacy in patients with low bleeding risk but loss its advantage in those with moderate-to-high bleeding risk.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was sponsored by a grant from the National Key Research and Development Project (No. 2016YFC1301300).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Qiang Shi

REFERENCES

- 1.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, et al. Authors/Task Force Members. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society Of Cardiology (ESC) and the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS) Developed with the special contribution of the European association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: An update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1235–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg PG, James S, Harrington RA, Ardissino D, Becker RC, Cannon CP, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes intended for reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A Platelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial subgroup analysis. Circulation. 2010;122:2131–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927582. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahlén A, Varenhorst C, Lagerqvist B, Renlund H, Omerovic E, Erlinge D, et al. Outcomes in patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel after acute myocardial infarction: Experiences from SWEDEHEART registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3335–42. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw284. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto S, Huang CH, Park SJ, Emanuelsson H, Kimura T. Ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel in Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese patients with acute coronary syndrome – Randomized, double-blind, phase III PHILO study. Circ J. 2015;79:2452–60. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0112. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu B, Lin H, Tobe RG, Zhang L, He B. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in East-Asian patients with acute coronary syndromes: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7:281–91. doi: 10.2217/cer-2017-0074. doi: 10.2217/cer-2017-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CH, Cheng CL, Kao Yang YH, Chao TH, Chen JY, Li YH, et al. Cardiovascular and bleeding risks in acute myocardial infarction newly treated with ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel in Taiwan. Circ J. 2018;82:747–56. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0632. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen IC, Lee CH, Fang CC, Chao TH, Cheng CL, Chen Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome in Taiwan: A multicenter retrospective pilot study. J Chin Med Assoc. 2016;79:521–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2016.02.010. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamon M, Filippi-Codaccioni E, Riddell JW, Lepage O. Prognostic impact of major bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. EuroIntervention. 2007;3:400–8. doi: 10.4244/eijv3i3a71. doi: 10.4244/EIJV3I3A71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornara S, Somaschini A, De Servi S, Crimi G, Ferlini M, Baldo A, et al. Prognostic impact of in-hospital-bleeding in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.076. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine GN, Jeong YH, Goto S, Anderson JL, Huo Y, Mega JL, et al. Expert consensus document: World Heart Federation expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:597–606. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.104. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang HJ, Clare RM, Gao R, Held C, Himmelmann A, James SK, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: A retrospective analysis from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J. 2015;169:899–905e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.015. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Xi S, Liu J, Qin L, Jing J, Yin T, et al. Switching between ticagrelor and clopidogrel in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention: Insight into contemporary practice in Chinese patients. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2016;18:F19–26. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suw034. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suw034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, Gage BF, Rao SV, Newby LK, et al. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: The CRUSADE (Can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress ADverse outcomes with early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) bleeding score. Circulation. 2009;119:1873–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.828541. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.828541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: A consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Qi J, Li Y, Tang Y, Li C, Li J, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor vs. Clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and chronic kidney disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:88–96. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13436. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng R, Butler K. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and tolerability of single and multiple doses of ticagrelor in Japanese and caucasian volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;52:478–91. doi: 10.5414/CP202017. doi: 10.5414/CP202017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon TJ, Tantry US, Park Y, Choi YM, Ahn JH, Kim KH, et al. Influence of platelet reactivity on BARC classification in East Asian patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Results of the ACCEL-BLEED study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:979–92. doi: 10.1160/TH15-05-0366. doi: 10.1160/TH15-05-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh RW, Secemsky EA, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, Gershlick AH, Cohen DJ, et al. Development and validation of a prediction rule for benefit and harm of dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year after percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2016;315:1735–49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3775. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farooq V, van Klaveren D, Steyerberg EW, Meliga E, Vergouwe Y, Chieffo A, et al. Anatomical and clinical characteristics to guide decision making between coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for individual patients: Development and validation of SYNTAX score II. Lancet. 2013;381:639–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60108-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]