Abstract

This study examined processes by which extracurricular participation is linked with positive ethnic intergroup attitudes in multiethnic middle schools in California. Specifically, the mediating roles of activity-related cross-ethnic friendships and social identities including alliances with multiple groups were examined in a sample including African American or Black, East or South-East Asian, White, and Latino youth (N = 1,446; Mage = 11.60 in sixth grade). Results of multilevel modeling suggested that in addition to activity-related cross-ethnic friendships, complex social identities mediated the association between availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities and ethnic intergroup attitudes. Results are discussed in terms of how activities can be structured to promote cross-ethnic relationships and complex social identities, as well as positive ethnic intergroup attitudes.

Most adolescents prefer to spend time with and befriend same-ethnic peers, even when opportunities for cross-ethnic interaction exist (e.g., Hamm, Brown, & Heck, 2005). Moreover, practices such as academic tracking keep students from different ethnic groups apart at school (Oakes, 1995; Rees, Argys, & Brewer, 1996). Given that affiliating with cross-ethnic peers is linked with a number of positive outcomes, including more positive attitudes about ethnic out-groups (e.g., Feddes, Noack, & Rutland, 2009), a key question is as follows: how can school contexts be structured to connect youth from different ethnic backgrounds? In this study, we examine the opportunities that extracurricular activities (i.e., school-based activities occurring outside of the regular curriculum, such as performing arts and sports) provide for fostering positive intergroup attitudes in urban middle schools. Our main goal was to extend research on contact theory (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998) by examining how extracurricular activities may not only facilitate close cross-ethnic friendships, but also complex and inclusive social identities, in a study spanning the sixth and seventh grade in ethnically diverse schools in the United States.

Extracurricular Activities and Positive Intergroup Attitudes

Prior research suggests that extracurricular activities are an ideal context for positive peer relations within schools. Unlike classroom settings that afford few opportunities for unstructured peer interaction, extracurricular activities frequently encourage (and at times also require) peer collaboration, providing an opportunity for youth to work together toward a common objective (e.g., as in team sports or drama; Dworkin, Larson, & Hansen, 2003; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2013). Often, youth also self-select activities out of intrinsic interest or enjoyment (Hansen & Larson, 2007). Hence, extracurricular activities are likely to facilitate positive peer interactions, and ultimately a greater understanding of peers involved in the activity. Indeed, youth recognize that their activities enable them to connect with peers sharing similar interests, to make new friends, to spend time with existing friends, and to find a sense of acceptance and belonging with one’s peers (Brown & Evans, 2002; Denault & Poulin, 2016; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2013; Schaefer, Simpkins, Vest, & Price, 2011). Although activities play important social functions facilitating positive peer interactions and friendships, few studies have investigated the ways in which activity participation in multiethnic schools is linked with positive cross-ethnic attitudes.

In multiethnic school settings, ethnically diverse extracurricular activities can provide an ideal context for positive interactions across ethnic groups (Moody, 2001; Watkins, Larson, & Sullivan, 2007). Many extracurricular activities meet the optimal conditions for intergroup contact identified by Allport (1954), such as common goals, equal status, and support from authorities for cross-ethnic collaboration (see also Dworkin et al., 2003; Pettigrew, 1998). Whereas in most classrooms students work independently toward their personal goals, members of the basketball team must collaborate to advance the ball down the court, and youth in a choir need to work together to produce a musical piece in harmony. Thus, compared to academic classes that frequently divide ethnic groups (e.g., Oakes, 1995), extracurricular activities are more likely to unite a diverse set of youth. In line with these assumptions, White athletes expressed more positive intergroup attitudes when they had a greater proportion of Black teammates (Brown, Brown, Jackson, Sellers, & Manuel, 2003). Therefore, we presume that multiethnic extracurricular activities will foster positive attitudes about ethnic out-groups.

Whereas there is some evidence suggesting that participating in extracurricular activities with peers of various ethnicities is linked with positive intergroup attitudes in high school (Brown et al., 2003; Patchen, 1982), we are not aware of any research examining these relations at an earlier developmental phase. Investigating intergroup attitudes during early adolescence seems particularly important, inasmuch as middle schools draw students from various neighborhood elementary schools, and hence are typically more diverse. In-group preference has also been shown to emerge as early as childhood (Bigler, Jones, & Lobliner, 1997; Dunham, Baron, & Carey, 2011), making it especially critical to examine intergroup attitudes in the expanding middle school context. Therefore, investigating the ways in which extracurricular activities are associated with intergroup attitudes seems particularly critical during early adolescence.

Given our goal to examine the link between extracurricular involvement and intergroup attitudes in multiethnic middle schools, we specifically focus on cross-ethnic friendships and social identities as two possible, developmentally relevant mediators. These two constructs are supported by past research examining how intergroup contact promotes positive intergroup attitudes through (1) cross-ethnic friendships (Feddes et al., 2009) and (2) identification with multiple social groups (Schmid, Hewstone, Tausch, Cairns, & Hughes, 2009). To our knowledge, however, no study has examined these mediators in the same study during early adolescence.

Cross-ethnic friendships as a mediator.

Close friendships become increasingly important during early adolescence, as youth turn to friends for validation, intimacy, and support (Berndt, 1982; Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). Given that the formation and maintenance of friendships are fostered by proximity, as well as common interests and activities (e.g., Clark & Ayers, 1992; Dworkin et al., 2003; Kandel, 1978; Nahemow & Lawton, 1975), it is reasonable to expect that multiethnic extracurricular activities (as settings for close interaction and shared interests) will foster cross-ethnic peer relationships (Dworkin et al., 2003; Patchen, 1982). Opportunities for friendships with out-group members are, in turn, important to positive intergroup attitudes (Pettigrew, 1998; Turner, Hewstone, Voci, Paolini, & Christ, 2007). For instance, in their study of German and Turkish children, Feddes et al. (2009) found that cross-ethnic friendship nominations were linked with more positive perceptions of out-group members (i.e., as friendly or smart). Thus, taking advantage of opportunities to make cross-ethnic friends in extracurricular activities should help foster more positive attitudes about other ethnic groups.

Social identity complexity as a mediator.

Research on adults suggests that complex social identities also help explain how out-group contact is linked with positive intergroup relations (Schmid, Hewstone, & Al Ramiah, 2013; Schmid, Hewstone, & Tausch, 2014; Schmid et al., 2009). Much like adults, young adolescents start to define themselves in terms of multiple social identities (e.g., I am a Latina basketball player and debate team member; Tanti, Stukas, Halloran, & Foddy, 2011; Verkuyten & Kinket, 1999). These selfdescriptors, and adolescents’ ability to see themselves fulfilling multiple roles simultaneously (e.g., self with family, friends, or teachers; Harter, 1999), partly reflect their newly developed multiple classification skills (Aboud, 1988; Bigler & Liben, 1992), as well as new opportunities for social affiliation.

Thus, self-definition becomes increasingly complex as youth have opportunities to identify with multiple roles, groups, and activities. In the context of multiethnic schools, it is then reasonable to expect that identifying with multiple social groups that include cross-ethnic peers might help account for how extracurricular activity involvement is associated with positive intergroup attitudes.

To capture the intersections of multiple social identities, we rely on a construct called social identity complexity. This construct is measured by assessing the perceived membership overlap between the groups with which a person aligns himself or herself (Roccas & Brewer, 2002). For example, the question for a Latina, who identifies herself as a basketball player and as part of the school debate team, is to what degree the members of these groups overlap. When she perceives the members of her salient social groups to overlap substantially (e.g., most debate team members are basketball players and Latinos), her social identity complexity is low because the groups converge. In contrast, when only a few debate team members are basketball players and Latinos, her social identity complexity is high because in-group members in one group belong to out-groups in the other two groups.

Complex social identities that bridge different ethnic groups can therefore diffuse boundaries between (ethnic) in-groups and out-groups. Greater social identity complexity (i.e., low convergence of groups) has been shown to be associated with positive attitudes about ethnic out-groups among young adolescents in multiethnic schools (Knifsend & Juvonen, 2013, 2014), as well as among adults in diverse neighborhoods (Miller, Brewer, & Arbuckle, 2009; Schmid et al., 2013). Because crossethnic availability underlies such identity complexity (e.g., Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014), as the boundaries defining one’s important social in-groups become increasingly diffused and inclusive through contact with different out-groups (Schmid et al., 2013) the social identity complexity construct might help account for the link between activity-based availability of cross-ethnic peers and intergroup attitudes. Whether social identity complexity can predict intergroup attitudes over and beyond cross-ethnic friendships is a question that, to our knowledge, has not yet been examined.

The Current Study

The main goal of this study was to examine how availability of cross-ethnic peers within extracurricular activities during the first year of middle school is related to ethnic intergroup attitudes 1 year later. Within the context of our study, extracurricular activities were broadly defined to include any school-based clubs or groups occurring outside of the regular curriculum; they varied across multiple dimensions, including activity interdependence (i.e., individual- or team-oriented) or number of hours per week. Capitalizing on a sample from 11 multiethnic urban middle schools with data collected at two waves spanning the sixth and seventh grades, we presume that initial cross-ethnic friendships in a new school setting are particularly meaningful to subsequent intergroup attitudes. Consistent with contact theory, we first hypothesize that activity-related cross-ethnic friendships in the sixth grade mediate the link between cross-ethnic availability in extracurricular activities in sixth-grade and ethnic intergroup attitudes at seventh grade. These associations are tested in our first mediational model. To determine whether friendships in extracurricular contexts play a particularly important role in intergroup attitudes, we also test whether cross-ethnic friendships outside of extracurricular activities are linked with subsequent intergroup attitudes.

For our second main hypothesis, we examine the role of social identity complexity as a mediator. We presume that in addition to earlier cross-ethnic friendships, the ways in which youth come to identify with multiple groups can also explain why youth in ethnically diverse extracurricular activities might have more positive intergroup attitudes. Thus, in a second mediational model, we hypothesize that greater social identity complexity at seventh grade mediates the association between earlier cross-ethnic exposure in extracurricular activities and concurrent intergroup attitudes, controlling for earlier activity-related cross-ethnic friendships when testing each association in the model. Although youth with many cross-ethnic friends are likely to have complex social identities, friendships are also formed with individuals outside of the groups with which youth identify. Hence, close relationships and social identities should each in turn contribute to how comfortable one feels about ethnic out-groups. Social identity complexity is assessed at a different time point, seventh grade, than sixth-grade cross-ethnic friendships for two reasons. Based on past research documenting that earlier cross-ethnic friendships shape subsequent attitudes toward those ethnic groups (Feddes et al., 2009; Levin, Van Laar, & Sidanius, 2003), we assess friendships at sixth grade. For social identity complexity, we have no data prior to seventh grade because pilot testing indicated that naming multiple identities was very difficult for many students during sixth grade. While school transitions can serve as a catalyst for changes in identity (e.g., French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006), we presume that identification with activities (as well as other social groups) does not occur immediately during the first year in a new school. Hence, unlike crossethnic availability in extracurricular activities and activity-related cross-ethnic friendships, which are assessed during the sixth grade, social identity complexity is measured only during the second year. To ensure that each social identity is meaningful, we also measure the perceived importance of each social identity named.

METHOD

This study relied on data from a large, longitudinal study investigating the associations between school ethnic diversity and psychosocial adjustment in 26 public middle schools (Grades 6 through 8) in a large metropolitan area in California. The schools were selected based on their ethnic composition, such that ethnic groups varied in their relative size across the schools. Analyses for the current study rely on data from the spring of the sixth and seventh grades from 11 multiethnic schools where social identity data were available. The current study extends earlier published cross-sectional analyses in a seventh-grade sample based on four schools (n = 622; Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014), by including data from seven additional schools and using sixth-grade data on cross-ethnic peers in schools and in extracurricular activities, as well as on cross-ethnic friendships. Schools sampled included students from middle socioeconomic status and working-class communities. The freereduced lunch eligibility ranged from 25% to 80%. The schools range from moderate (n = 706) to large (n = 2,065) in size and reflect the overall diversity of the metropolitan area.

Participants

The sample from these 11 schools was comprised of 2,826 students. Of this sample, 75% (n = 2,131) were involved in at least one extracurricular activity during the sixth grade. Given the hypothesis regarding intergroup attitudes, where attitudes were assessed about the four major pan-ethnic groups, our analyses relied on a subsample of extracurricular participants who self-reported themselves as African American or Black, East or South-East Asian, White, or Latino. Of the 1,543 participants from four major pan-ethnic groups, 97 were further excluded because each of these was the only student participating in a particular extracurricular activity (n = 62), or because they did not report any friends (n = 35), meaning we could not compute scores reflecting cross-ethnic availability or cross-ethnic friendships. The final analytic sample (N = 1,446; 54% female; Mage = 11.60 in sixth grade) was 44% Latino (n = 631), 28% White (n = 397), 17% African American or Black (n = 250), and 12% East or South-East Asian (n = 168).

Procedure

In sixth grade, students were recruited to participate in a study examining what school and life is like for sixth graders like themselves. After a short presentation, students brought home parent consent forms and informational letters explaining the study. To increase the number of returned consent forms (either allowing or not allowing study participation), students and parents returning the consent form were entered into a raffle of $50 gift cards. The average recruitment rate (i.e., average number of students returning consent forms) across all schools was 81% (range = 72%–94%). Only students who returned a parent consent form permitting participation and assented to participate at Wave 1 in fall of sixth grade were included in the study (average retention rate = 83%).

Sixth-grade data on school diversity, cross-ethnic availability at school, cross-ethnic availability in extracurricular activities, and cross-ethnic friendships in and outside of activities were assessed in the spring. Data on social identity complexity and ethnic intergroup attitudes were collected during seventh grade from the same adolescents, with the social identity complexity measure requiring two class periods. Researchers, who were the principal investigators, graduate students, or trained undergraduate students, read most items aloud to the students. Students received $5 for their participation at each wave of data collection in the sixth grade (i.e., fall and spring) and $10 in the seventh grade.

Measures

Demographic covariates.

Students reported their gender, ethnic group, language spoken at home, and immigration (i.e., generational) status in the fall of sixth grade. Ethnicity, used both as a covariate and in the social identity complexity measure, was reported based on a list with 13 options. Parents also reported their highest level of education in the fall of sixth grade.

School ethnic diversity.

School ethnic diversity in the sixth grade was calculated using data from the California Department of Education (2011) to consider as a school-level covariate. The ethnic composition of each school (Ds) was calculated using the formula for Simpson’s Index of Diversity (Simpson, 1949), , where p is the proportion of students in the sixth grade who are in ethnic group i. Simpson’s Index of Diversity gives the probability that two students randomly selected from a group (e.g., sixth grade) will belong to different ethnic groups. Based on California Department of Education classifications, calculations of school diversity relied on sixth graders classified as African American, Asian, Hispanic or Latino, White, Filipino or Pacific Islander, Native American, Multiethnic, and Not Reported. Schools ranged in their diversity from moderately diverse (Ds = .48) to diverse (Ds = .72), with an average score of .62 (SD = 0.08).

Availability of cross-ethnic peers at school.

To be able to control for the availability of cross-ethnic classmates in sixth grade at school, we relied on California Department of Education statistics (2011). For every ethnic group within each of the 11 schools, a score was computed reflecting the proportion of sixth-grade peers who belong to ethnic out-groups (i.e., number of sixth-grade students of all other ethnic backgrounds divided by the total number of sixth-grade students, minus oneself). On average, 60% of students’ grademates represented ethnic out-groups (SD = 0.18; range = .32–.99).

Availability of cross-ethnic peers in extracurricular activities.

Our predictor variable, availability of cross-ethnic peers in extracurricular activities, was calculated based on sixth-grade activities offered during the year at each school. Students were asked to check all of the activities they were involved in during the sixth grade. To be able to rely on school-specific extracurricular offerings, we requested lists of all organized clubs and activities that occur throughout the day (e.g., before school, during lunch, or after school) at each school. Extracurricular activities used in the current study consisted of sports (e.g., intramural soccer), performing arts (e.g., drama), visual arts (e.g., art club), academic groups (e.g., leadership), special interest groups (e.g., gardening club), and afterschool programs (e.g., boys’ and girls’ clubs). Across the 11 schools, there were 267 activities offered during the sixth grade (range: 5–53 activities per school), consisting of approximately 57 members (M = 56.90, SD = 45.90).

The ethnic composition of extracurricular activities was calculated using the self-reported ethnicity of each participant in the study. Because we relied only on data reported by study participants (i.e., possibly not all activity members), this measure of ethnic composition was an estimation of the composition of the activity. However, given the level of study participation (over 80%), we presumed that this estimate is representative of the ethnic compositions of activities. While this measure only accounts for sixth-grade peers in the activity, it was assumed that many middle school activities include solely or mainly same-grade students. Availability of cross-ethnic peers in the same grade is also especially relevant to these analyses, given that friendships are typically formed among samegrade peers (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). To create the main variable of interest, the number of cross-ethnic classmates in one’s activity was summed and divided by the total number of peers in one’s activity to obtain a proportion score of activity-based cross-ethnic peers. For adolescents in multiple activities (72%), the denominator consisted of the total number of peers summed across all activities, with those who were in multiple activities with the student counted only once. Similarly, the numerator was the sum of all cross-ethnic peers in one’s activities, with those in multiple activities counted once. On average, over half of the members of one’s activities were from a different ethnic group from one’s own (M = 0.65, SD = 0.20). This estimate is consistent with the high ethnic diversity of the sampled schools.

Cross-ethnic friendships.

Cross-ethnic friendships are the first mediator in our main analyses. Students were asked to provide an unlimited number of nominations of their “good friends” who were in the sixth grade and attended the same school. To assess how many of these friends were of a different ethnic background than the participant, students were asked to indicate whether each named friend was of the same or a different ethnic group as their own. Consistent with prior research on the links between cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, and intergroup attitudes (Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014), this subjective measure of friends’ ethnicity, rather than selfreported ethnic identification by each friend, was used. We presumed that the degree to which youth perceive their friends to belong to different ethnic groups is particularly meaningful psychologically. This measure also enabled us to include friendships with multiethnic peers. Two variables reflecting cross-ethnic friendships were calculated: one for activity-related friendships and the other for friendships outside of activities.

The self-reported extracurricular participation of all students in our sample at each school was used to determine the members in each activity, and subsequently to calculate the proportion of one’s same-grade friends in their activities who belong to a different ethnic group. To be able to calculate the proportion of cross-ethnic friends in the extracurricular activity, we computed for each fellow activity member whether that person (1) was nominated as a friend and (2) whether or not the friend was reported to be of a different ethnic background. For youth in only one activity, the denominator was the number of friends in their activity, and the numerator was the number of activity-related cross-ethnic friends. For youth in multiple activities, the denominator (the total number of activityrelated friends) was defined as the number of friends who were in at least one activity with the student, with those in multiple activities counted only once, and the numerator was the number of those friends who were cross-ethnic. Scores can range from 0 to 1, with a high score indicating that many of one’s activity-related friends are cross-ethnic. Seventy-four percent of the sample had at least one friend who was in one or more activities. On average, approximately half of one’s activityrelated friends were cross-ethnic (M = 0.46, SD = 0.42).

To be able to examine whether other out-ofactivity cross-ethnic friends were also related to intergroup attitudes, another proportion score was calculated. Cross-ethnic friendships outside of activities consisted of the number of nonactivity friends perceived to be of other ethnic backgrounds divided by the total number of nonactivity friends. On average, 40% of one’s out-of-activity friends were cross-ethnic (SD = 0.39).

Social identity complexity

The second mediator tested, social identity complexity, was assessed using a measure based on an adult version (Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Roccas & Brewer, 2002), developed by Knifsend and Juvonen (2013, 2014). As mentioned earlier, social identity complexity was first measured in the seventh grade to afford youth the time to develop meaningful social identities in a new school context. To capture multiple social identities and their overlap, data were collected on two separate days. Participants were first asked to list three social groups that described them at seventh grade. Examples of various in-school and outof-school groups that could describe them were provided (e.g., extracurricular activities, sports, religious groups, or social groups) and with four to five examples of each to ensure that young adolescents understood the task (cf., Brewer & Pierce, 2005). Students were then asked to imagine that they were filling out a new Facebook page describing themselves to people who do not know them, and to list three groups that best describe them as a person.

After identification of social groups on the first day of data collection, research assistants individualized each participant’s questionnaire with the three social identity groups listed on the first day and one additional group membership, selfreported ethnic group, totaling four groups. Ethnicity was used as the fourth social identity because we expected the overlap between one’s ethnic group with their other social groups to be particularly relevant to ethnic intergroup attitudes (Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014). During the second day of data collection, participants then rated the group membership overlap of each bidirectional pairing of their four groups. To orient them to the task, an example was provided where they estimated “How many soccer players are seventh graders?” and “How many seventh graders are in soccer?” on a 5-point scale (1 = almost all; 5 = hardly any). Relying on the same 5-point scale, participants then rated the 12 pairings of their own social groups (e.g., “How many people in [Group A] are in [Group B]? How many people in [Group B] are in [Group A]?”). Social identity complexity scores were calculated as the mean of the 12 ratings reflecting the overlap of the four groups. A high score indicates low perceived membership overlap among groups (i.e., high social identity complexity). On average, adolescents perceived between about half and a few members of one in-group to belong to another in-group (M = 3.25, SD = 0.64), suggesting moderate complexity.

Reliability was calculated using a Spearman– Brown split-half coefficient. The 12 ratings were divided into two subsets, such that bidirectional pairings were in different subsets (i.e., “How many people in [Group A] are in [Group B]?” in one subset, “How many people in [Group B] are in [Group A]?” in the other subset). The Spearman–Brown reliability coefficient was .94, suggesting that the social identity complexity measure has good internal consistency.

Importance of social identities.

On the second day, participants were asked to rate the importance of the four groups with which they identified. Although this measure is not included in our main analyses, it was important to verify that identities listed were in fact valued, given that social identity complexity should be based on meaningful social groups (Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Youth rated the importance of the three self-identified social groups as well as their ethnicity (e.g., “How important is it to you that you are a [Group A] member?”). Responses were on a 5-point scale (1 = definitely not important; 5 = definitely important). The average importance of ethnicity (i.e., the only group identity not self-nominated; M = 4.07, SD = 1.08) was similar to the overall importance ratings across all types of identities (M = 3.97, SD = 1.05).

Ethnic intergroup attitudes.

Items assessing the degree to which seventh-grade students wanted to associate with ethnic in-group and out-group members were used to calculate social distance (Bogardus, 1933; Jones, 2004; Marsden, 1988), our outcome variable reflecting ethnic intergroup attitudes. We chose to focus on developmentally relevant behavioral items, part of a larger battery of intergroup attitudes measures, to expand on prior research on social identity complexity that has relied mainly on affective measures of in-group bias (e.g., Schmid et al., 2009, 2013).

Participants were first provided with an example where they were asked to rate whether they would like to eat lunch, get together at their house, dance together at a party, or sit together on a school bus with kids who were in the eighth grade (i.e., outgroup based on grade), on a 5-point scale (1 = no way!; 5 = for sure yes!). After completing the example, participants responded to the same four items for Asian, Black, Latino, and White youth (e.g., “Now think about doing these things with kids who are [Ethnic Group]. Would you want to eat lunch with...”), for a total of 16 items. Blocks of the four items within each ethnic group were presented in four different, randomly assigned orders. Consistent with prior studies of social identity complexity (Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014), we relied on an aggregated measure of social distance from all three ethnic outgroups. Social distance was calculated by subtracting the average of 12 items for three ethnic out-groups from the average of four items for members of one’s own ethnic group. Because items were rated on a 1–5 scale, social distance scores could range from –4 (high out-group preference) to 4 (high in-group preference). Thus, higher scores indicated greater social distance (i.e., less positive ethnic intergroup attitudes), whereas lower social distance scores indicate that ethnic out-groups are rated more similarly to one’s in-group (i.e., more positive ethnic intergroup attitudes). On average, adolescents rated their in-group higher than outgroups (M = 0.46, SD = 0.69). Cronbach’s alphas calculated among four in-group items (α = .85) and 12 out-group items (α = .94) indicated good internal reliability.

RESULTS

The results section consists of three parts. To preface our main analyses focusing on extracurricular activity–related cross-ethnic friendships and complex social identities, we first describe ethnic group differences in extracurricular participation and in cross-ethnic availability in activities. Second, the social identity groups listed by young adolescents are examined. In the third part, we test our main hypotheses. Specifically, we examine first whether cross-ethnic friendships mediate the association between cross-ethnic availability in extracurricular activities and ethnic intergroup attitudes. Subsequently, we test whether social identity complexity can help explain how cross-ethnic availability in activities is associated with positive intergroup attitudes, over and above cross-ethnic friendships controlled for in each model.

Ethnic Context of Extracurricular Activities

Ethnic group differences in activity participation in the sixth grade were found to be significant, F (3,1433) = 6.75, p < .001, η2 = .01, controlling for gender, language spoken at home, generational status, and parental education. Post hoc t-tests with a Bonferroni correction suggested that African American or Black youth were less involved than East or South-East Asian and White youth, ps < .01. Similarly, Latino sixth graders were less involved than their East or South-East Asian and White peers, ps < .01. Because our main predictor of interest was availability of cross-ethnic peers in extracurricular activities, ethnic differences in availability were also investigated. Possibly reflecting their smaller group size in our sample and lower rates of extracurricular involvement, African American or Black youth had greater cross-ethnic availability in activities than East or South-East Asian, White, and Latino peers, ps < .01. Similarly, both East or South-East Asian and White youth had more crossethnic peers in their activities than Latino youth, the largest ethnic group in our sample, ps < .001. Interactions by gender were also explored but were not significant.

Although various types of activities could not be statistically compared in our main analyses because the majority of youth (72%) were involved in multiple activities, descriptive analyses suggested the greatest availability of cross-ethnic peers in visual arts activities (M = 0.76, SD = 0.04), followed by performing arts (M = 0.72, SD = 0.14), academic activities (M = 0.69, SD = 0.25), and sports (M = 0.63, SD = 0.25). In general, this pattern was similar across ethnic groups. Due to the small size of some activities and because a majority of youth were in multiple activities, we could not test whether different types of activities in and of themselves were related to our variables of interest. Rather, we focus on the opportunities that any extracurricular participation provides for cross-ethnic friendships, complex social identities, and positive intergroup attitudes.

Social Identities

Trained research assistants categorized social groups into nine categories with high inter-rater reliability, κ = .90. Out-of-school sports (e.g., basketball; 45% of students) were the most common groups listed, followed by groups based on religion (e.g., Christian; 43%), peer crowds (e.g., popular; 35%), and school-based activities (e.g., cooking club; 29%) that are a focus of this study. Out-ofschool performing arts (e.g., dance; 28%), gaming (e.g., video gamer; 18%), special interests (e.g., cooking; 18%), out-of-school visual arts (e.g., animation; 9%), and academic orientation (e.g., good students; 6%) were also listed.

Testing Mediational Effects of Cross-Ethnic Friendships and Social Identity Complexity

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) was used in the current study. HLM not only allows for the nested nature of the data to be accounted for (i.e., students within schools), but enabled us to analyze how both crossethnic friendships and social identity complexity mediate the association of cross-ethnic availability in activities and intergroup attitudes.

Multiple imputation.

Multiple imputation procedures in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) using PROC MI were used to estimate social identity complexity and ethnic intergroup attitudes data for youth in our analytic sample who were missing data (20% for social identity complexity; 14% for ethnic intergroup attitudes). Missing data for social identity complexity were most commonly due to failing to list three social groups, failing to respond to all 12 items, or being absent on one or both data collection days. In the current sample, boys (23% vs. 18% for girls) and African American or Black youth (29%, vs. 20% for Latinos, 18% for Whites, and 16% for East or South-East Asians) were more likely to have missing data for social identity complexity. Demographic groups did not differ in missing data for ethnic intergroup attitudes. Auxiliary variables that were consistent with our hypotheses were included in the multiple imputation, including gender, ethnicity, language spoken at home, generational status, parental education, school-level ethnic diversity, cross-ethnic availability at school and in activities, and cross-ethnic friendships. Given the percentage of missing data, five data sets were imputed to achieve at least 95% efficiency of the imputation estimators, based on prior recommendations (e.g., Yuan, 2000). Main analyses averaged results across the five imputed data sets. The results reported below are similar to those obtained when relying on listwise deletion and maximum likelihood procedures.

Unconditional models.

Unconditional models examining the degree to which schools vary in cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, and ethnic intergroup attitudes were first tested in SAS version 9.2 using PROC MIXED. Variance at the activity level was not tested because cross-ethnic availability and cross-ethnic friendships were aggregated across multiple activities for youth in two or more activities, meaning that there were not true activity-level groupings. A fully unconditional, two-level model showed variability of students within schools (measured with the intraclass correlation coefficient, or ICC) for activity-related crossethnic friendships (ICC = 7% of total variance, χ2 = 312.02, p < .001), cross-ethnic friendships out of activities (ICC = 7% of total variance, χ2 = 158.08, p < .001), social identity complexity (ICC = 3% of total variance, χ2 = 38.06, p < .001), and intergroup attitudes (ICC = 2% of total variance, χ2 = 47.38, p < .001). Thus, subsequent models considered students within schools using HLM.

Mediator models.

Correlations of main model variables are presented in Table 1. To examine multiple mediators in HLM, procedures employed in prior studies (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001; Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, & Petty, 2011; Tormala, Petty, & Brinol, 2002; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010) were followed using SAS PROC MIXED. First, we tested how activity-related cross-ethnic friendships in sixth grade (M1) mediate the association of sixthgrade availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities (X) and seventh-grade ethnic intergroup attitudes (Y) by examining the a path (X to M1) and the b path (M1 to Y, with X in the model). In a second mediational model, the role of the second mediator (M2) is then assessed by examining its own a path (X to M2) and b path (M2 to Y, with X in the model), while controlling for the first mediator variable (M1). In this study, the second mediator is seventh-grade social identity complexity (M2), and its mediational role is examined while controlling for cross-ethnic friendships in the sixth grade (M1) in each path. The Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation (MCMAM; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Selig & Preacher, 2008) generates 95% confidence intervals (CI) with 20,000 repetitions of indirect effects based on unstandardized regression coefficients (a*b), in R-3.3.1 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Confidence intervals that do not contain 0 are considered significant at α < .05.

Table 1:

Pearson’s Correlations of School Diversity, Cross-Ethnic Availability in Activities, Cross-Ethnic Friendships, Social Identity Complexity, and Social Distance From Ethnic Out-Groups

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School diversity | - | .48*** | .55*** | .19*** | .18*** | .11*** | −.17*** |

| 2. Availability of cross-ethnic peers at school | - | .83*** | .25*** | .10** | .18*** | −.15*** | |

| 3. Availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities | - | .33*** | .07* | .18*** | −.15*** | ||

| 4. Cross-ethnic friends in activities | - | −.01 | .15*** | −.16*** | |||

| 5. Cross-ethnic friends—other | - | −.06 | −.03 | ||||

| 6. Social identity complexity | - | −.15*** | |||||

| 7. Social distance | - |

Note. Cross-ethnic availability at school and cross-ethnic friends were calculated as a proportion of sixth-grade peers at school and friends, respectively. Cross-ethnic friends—other indicates the proportion of outside-of-activity friends who were cross-ethnic. Social distance is the measure reflecting ethnic intergroup attitudes (i.e., lower social distance reflects more positive intergroup attitudes).

N = 1,446 adolescents.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

All variables of interest were measured at the individual level. Based on recommendations by Zhang, Zyphur, and Preacher (2009), both withinschool and between-school effects were included in each model by group-mean centering Level 1 predictors, and by entering the mean of each predictor (i.e., availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities, cross-ethnic friendships, or social identity complexity) at each school as a Level 2 predictor. The group mean of each predictor at each school is entered to parse out individual- versus school-level effects. Covariates in each equation included ethnicity, gender, language spoken at home, generational status, parental education, and cross-ethnic availability at school at Level 1, and school-level ethnic diversity and means of all relevant predictors at Level 2.

Cross-ethnic friendships as a mediator.

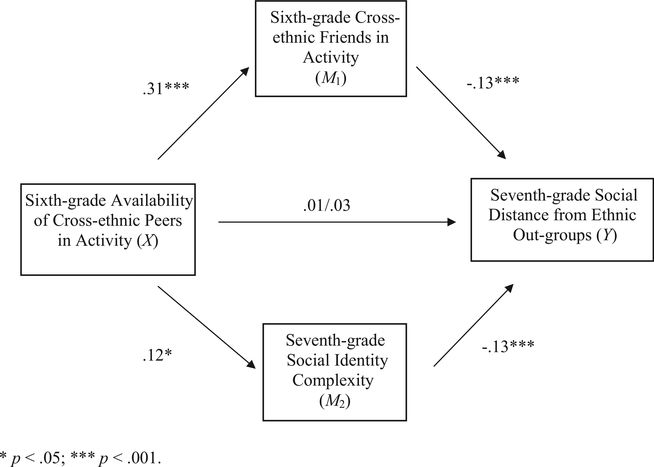

First, greater availability of cross-ethnic peers in one’s extracurricular activities in the sixth grade (X) was associated with a greater proportion of activityrelated cross-ethnic friendships in sixth grade (M1), B = .82, SE = .13, β = .31, p < .001 (a path). Second, a greater number of cross-ethnic friendships in activities (M1) was associated with lower distance from ethnic out-groups in seventh grade (i.e., more positive intergroup attitudes; Y), B = .22, SE = .05, β = .13, p < .001 (b path; see Figure 1). Availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities (X) was not directly linked with intergroup attitudes (Y). Coefficients reflecting school-level means of cross-ethnic availability in activities and cross-ethnic friendships at Level 2 did not play a significant role in any of these associations. MCMAM testing (Preacher & Selig, 2012; Selig & Preacher, 2008) suggested a small, but significant, indirect effect of cross-ethnic friendships, a*b =–.18, 95% CI [.29, –.09], completely standardized a*b = –.04. In line with our hypothesis, youth in activities with more cross-ethnic peers had more activity-related crossethnic friends, which in turn were linked with lower social distance (i.e., positive ethnic intergroup attitudes). Analyses testing cross-ethnic friendships outside of activities as a mediator were not significant, suggesting that compared to any cross-ethnic friendships, those formed specifically within extracurricular activities played a unique role.

FIGURE 1.

Standardized regression coefficients of mediator models. The first coefficient of X on Y reflects the direct link. The second coefficient of X on Y reflects the direct link with M1 (cross-ethnic friends in activity) and M2 (social identity complexity) in the model. Associations between X and M1 and M1 and Y are from the first mediational model (testing cross-ethnic friendships as a mediator; coefficients reported in text). Associations between X and Y, X and M2, and M2 and Y are from the second mediational model (testing social identity complexity as a mediator; coefficients reported in Table 2).

Social identity complexity as a mediator.

Subsequently, as shown in Table 2, social identity complexity in seventh grade as a mediator was entered into each model, to test its role over and above cross-ethnic availability at school and friendships. Greater availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities in sixth grade (X) was associated with higher social identity complexity in seventh grade (M2). Moreover, greater social identity complexity (M2) was associated with lower social distance (i.e., more positive intergroup attitudes) at the same time point (Y), even when earlier activity-related cross-ethnic friendships (M1) were included in the model (see Figure 1). School-level means were not significant predictors. MCMAM testing reflected a small, but significant, indirect effect of social identity complexity, a*b = .–08, 95% CI [–.16, –.01], completely standardized a*b = .02.

Table 2.

Second Mediational Model Testing Associations of Availability of Cross-Ethnic Peers in Activities (X), Social Identity Complexity (M2), and Social Distance From Ethnic Out-Groups (Y)

| Predictors | a Path | b Path | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Intercept | 2.96*** | .38 | 0.59 | 1.22 | ||

| Level 1 | ||||||

| African American | −0.16* | .07 | −.10 | 0.02 | 0.07 | .01 |

| Asian | −0.01 | .08 | −.01 | 0.24** | 0.09 | .11 |

| Latino | −0.09 | .06 | −.07 | 0.17** | 0.06 | .12 |

| Male | −0.08 | .04 | −.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | .04 |

| Less English | −0.02 | .06 | −.01 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −.01 |

| 1st generation | 0.03 | .08 | .01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .01 |

| 2nd generation | 0.02 | .05 | .02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | .03 |

| Did not finish high school | −0.00 | .08 | −.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | −.04 |

| High school diploma or GED | −0.17* | .08 | −.08 | −0.08 | 0.08 | −.04 |

| Some college | 0.02 | .07 | .01 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −.02 |

| Four-year college | 0.04 | .07 | .02 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −.03 |

| Did not respond | 0.11 | .09 | .05 | 0.06 | 0.08 | .03 |

| Availability of cross-ethnic peers at school | 0.21 | .25 | .06 | −0.25 | 0.23 | −.06 |

| Availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities | 0.50* | .23 | .12 | 0.13 | 0.22 | .03 |

| Cross-ethnic friends in activities | 0.15** | .05 | .09 | −0.20*** | 0.05 | −.11 |

| Social identity complexity | −0.15*** | 0.03 | −.13 | |||

| Level 2 | ||||||

| School diversity | −0.52 | .78 | −.07 | −1.25 | 0.88 | −.15 |

| Availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities | 0.37 | .64 | .07 | 0.73 | 0.68 | .12 |

| Cross-ethnic friends in activities | 0.37 | .28 | .07 | −0.23 | 0.33 | −.04 |

| Social identity complexity | −0.18 | 0.36 | −.03 | |||

Note. The a path model tests the link between availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities (X) and social identity complexity (M2; coefficient bolded). The b path model tests the association between social identity complexity (M2) and social distance from ethnic out-groups (Y; coefficient bolded).

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

In sum, these results suggest that in multiethnic schools extracurricular activities were associated with more positive intergroup attitudes through two developmentally salient mechanisms: close relationships and social identities. Thus, to promote positive attitudes toward different ethnic groups, youth needed to capitalize on opportunities provided by ethnically diverse activity settings by forming close friendships within their activities and by identifying with cross-cutting social groups.

DISCUSSION

Extending research on contact theory (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998), this study considered participation in school-based, multiethnic extracurricular activities among young adolescents. We demonstrated first how cross-ethnic friendships in the context of activities help explain the association between availability of cross-ethnic peers in activities and positive intergroup attitudes. Second, we showed how complex and inclusive social identities further help account for this link. To our knowledge, the current study is one of the first to document processes by which extracurricular participation might help lower ethnic-based prejudice in multiethnic middle schools. This study also complements research on extracurricular involvement that has focused mainly on the personal benefits (e.g., higher achievement or psychological adjustment; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006) of such involvement in high school by extending analyses to intergroup relations during early adolescence.

To understand how and why extracurricular involvement is associated with positive intergroup relations in multiethnic schools, we first examined the role of cross-ethnic friendships. Consistent with our hypothesis based on contact theory (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998), greater cross-ethnic availability in activities in the sixth grade was associated with more activity-related cross-ethnic friends in sixth grade, which in turn were linked with more positive attitudes about other ethnic groups (i.e., lower social distance) in seventh grade. It is important to note that it was cross-ethnic friendships in activities, and not just any school-based cross-ethnic friends, that helped explain how crossethnic availability in activities was linked with positive intergroup attitudes. Potentially, friendships in activities might differ in important ways from other school-based friendships. Unlike classroombased friendships that may be formed based on proximity (e.g., students in the same English class), extracurricular involvement is voluntary, a purposefully sought out activity based on interest (e.g., Clark & Ayers, 1992; Kandel, 1978; Nahemow & Lawton, 1975). Thus, the personal bonds fostered by these activities appear to be particularly powerful.

To further understand the link between extracurricular activities and intergroup attitudes, we also examined the role of complex, inclusive social identities. Relying on a relatively novel construct, social identity complexity, we demonstrated that such complexity also helps account for the association between earlier exposure to cross-ethnic peers in extracurricular activities and subsequent intergroup attitudes. Extending prior research on school-based availability of cross-ethnic peers (Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014), we showed that exposure to other ethnic groups in extracurricular activities in sixth grade is related to more complex and inclusive social identities in seventh grade. Consistent with research on adults living in ethnically diverse neighborhoods, greater social identity complexity, in turn, was associated with more positive ethnic intergroup attitudes (i.e., lower social distance) at the same time point (Schmid et al., 2013). Belonging to activities with peers from other ethnic groups may help blur the boundaries perceived between ethnic in-groups and out-groups (Brewer & Pierce, 2005). For example, youth in ethnically diverse activities may view their ethnic in-group as linked to ethnic out-groups by a common, superordinate social identity, which has been shown to be associated with more positive intergroup attitudes (e.g., Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000). Given that activities have been shown to foster identity exploration (e.g., Dworkin et al., 2003), they may relate especially strongly to positive intergroup attitudes when identities are seen as inclusive of others.

Together, these results support the important role of extracurricular settings in connecting youth from different ethnic backgrounds in multiethnic schools. Although some of the effects were small, we consider them practically meaningful given substantial statistical controls of individualand school-level variables. Our analyses controlled for school-level ethnic diversity and crossethnic availability, underscoring the specific role of extracurricular involvement in intergroup relations. Unlike educational practices that can separate youth from different ethnic backgrounds, such as academic tracking (Rees et al., 1996), the shared interests and common goals of activities (Dworkin et al., 2003) are more likely to bring a diverse set of youth together. Moreover, activities differ from the typical classroom context in important ways, including greater engagement and an orientation toward experiential learning driven by youth themselves, which is often achieved through peer interdependence and collaboration (Vandell, Larson, Mahoney, & Watts, 2015). Given the high degree of relatively informal, cooperative interaction among activity members, ethnically diverse activities may be uniquely situated to promote positive intergroup contact in school settings (Moody, 2001). When activities interest ethnically diverse groups of students, and are designed to promote positive peer interactions among all members, close crossethnic ties and inclusive social identities are likely to develop.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Given that ethnically diverse extracurricular activities can offer a setting for cross-ethnic friendships and complex, inclusive social identities, understanding availability of cross-ethnic peers across different types of activities is important. While we could not model this explicitly because 72% of youth in our sample belonged to multiple activities, descriptive analyses suggested that cross-ethnic availability was greatest in performing and visual arts. Arts activities may be less susceptible to ethnic cleavages that have been found primarily in sports and academic activities (e.g., soccer or school newspaper; Clotfelter, 2002). Additional research is needed to better understand whether and why activities vary in their cross-ethnic appeal (e.g., specific factors, such as competitive tryouts), especially given that some of the differences noted are small.

In addition to examining cross-ethnic appeal of arts, sports, and academic-oriented activities, further research is also needed to systematically test how to maximize the ways in which diverse extracurricular activities can foster the development of cross-ethnic friendships and complex social identities. Extracurricular activities that fulfill the specific tenets of contact theory, such as common goals and equal status, should promote more positive intergroup attitudes (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998). Although we were unable to test such differences in the current study due to the large proportion of youth engaging in multiple activities, qualitative research suggests that cross-ethnic friendships are indeed more common in cooperative or highly interdependent activities, such as drama or orchestra (Patchen, 1982). Considering this question is critical given that schools are in the position to structure extracurricular settings to promote optimal cross-ethnic contact (Moody, 2001). Additionally, our measure of extracurricular participation did not consider intensity (i.e., hours per week), duration, or psychological engagement, dimensions that are receiving greater attention as important to adolescent outcomes (e.g., Vandell et al., 2015). We presume that with greater participation (e.g., higher intensity), effects of cross-ethnic availability in activities would be amplified. Future research focusing on the structure of activity contexts and type of participation would help inform programs on how best to promote conditions facilitating positive ethnic intergroup attitudes.

Further exploration of longitudinal effects is also needed. Guided by contact theory and prior research on social identity complexity, we presumed that friendship formation and social identity development take place in the context of extracurricular activities, rather than cross-ethnic friendships and complex social identities guiding activity selection. No alternative directions of effects were tested in this study because we had systematic and reliable data on school-verified extracurricular activities (and activity-related friendships) only at sixth grade, whereas social identity complexity was successfully assessed only at seventh grade. Although there are good reasons to expect that (1) initial cross-ethnic experiences in a new school setting are particularly meaningful in affecting subsequent intergroup attitudes, and (2) identification with multiple groups requires more time than dyadic friendship formation in a new school, intergroup attitudes ideally should have been assessed at a third time point. With multiple data points for all constructs, it would then also be possible to examine stability and change in cross-ethnic availability in activities, cross-ethnic friendships, or social identity complexity. Future research could also collect data in elementary school or in high school to examine how prior cross-ethnic availability affects cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, and intergroup attitudes in middle school, or the extent to which these associations extend over time.

Research investigating school-level effects is also needed. Although individual-level and school-level predictors were included in our main models, all of our associations operated at the individual level. The lack of school-level effects may be due to the low number of schools (n = 11) or to a relatively narrow range of ethnic diversity in these schools (i.e., from moderate to high). Hence, we do not know whether the current findings will replicate in less diverse extracurricular contexts with fewer opportunities for cross-ethnic interaction. Also, although ethnic identity was rated as important to self-definition as other social identities in our multiethnic sample, the meaning of ethnic group membership can vary in different types of school settings (e.g., Grossman & Charmaraman, 2009). Thus, future research is needed to test whether these findings replicate in less diverse school settings.

Lastly, further development of the social identity complexity measure is needed. In addition to considering intersections in the members across different, mostly achieved groups (e.g., based on extracurricular activities), future research examining the meaning of multiple ascribed identities (e.g., based on gender or ethnicity) would be important. Employing an intersectional approach that examines how ethnicity and gender combine to constitute a distinct, meaningful identity (e.g., Asian male, in addition to Asian and male separately; Rogers, Scott, & Way, 2015), for example, may help us to better understand the experience of belonging to multiethnic activities for youth from various backgrounds. Additionally, our measure of social identity complexity, asking youth to imagine that they were filling out a Facebook page and describing themselves to those who do not know them already, may have been more likely to elicit achieved social identities. Future research could provide an open-ended prompt to assess which social identities are most likely to be reported spontaneously.

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The current study suggests ways in which extracurricular involvement is beneficial during the middle school years. First of all, the level of extracurricular involvement was very high, with 75% of the larger sample involved in at least one activity. Given that friendships gain new meaning in early adolescence (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995), and that this developmental phase is also critical for developing multiple social identities, it may be especially crucial for young adolescents to try out and participate in extracurricular activities. In middle school, activities are typically less time-intensive than in high school, and indeed 72% of extracurricular participants were engaged in multiple activities. These high levels of participation, and the positive psychosocial correlates documented in this study, suggest that middle school activities should not be the first programs to be cut during times of budget reductions.

Our findings also underscore the importance of extracurricular activities that are accessible to all youth, especially those from minority backgrounds who are less likely to participate (e.g., Brown & Evans, 2002). Given ethnic differences in participation found in the current study, it may be particularly important for schools to provide a number of activity options that appeal to a range of interests, skills, and backgrounds. Schools also may be in the position to encourage all students to participate by offering activities during school hours, defraying the costs of participation, and communicating with parents the utility of extracurricular involvement (Brown & Evans, 2002; Simpkins, O’Donnell, Delgado, & Becnel, 2011). When activities are ethnically diverse, those in charge of running them (i.e., coaches or teachers) are also in the position to encourage positive cross-ethnic interaction in activities in ways that facilitate cross-ethnic friendships, and to foster a strong sense of belonging to a common activity (e.g., Houlette et al., 2004). In the event that schools (and subsequently, their extracurricular activities) are ethnically homogenous, it may be especially important to encourage youth to participate in community-based programs (e.g., community sports leagues or church youth groups) that include diverse youth, to foster positive cross-ethnic peer relations. Findings of the current study clearly indicate that extracurricular involvement can play a critical role in fostering positive intergroup relations in multiethnic settings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health. Any opinion, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health. This material is also based on the work supported by the American Association of University Women American Dissertation Fellowship, and the Provost’s Research Incentive Fund at California State University, Sacramento. The authors would like to thank members of the UCLA Middle School Diversity Project for their assistance with data collection, as well as Andrew Fuligni, Sandra Graham, and Tara K. Scanlan for their comments on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Casey A. Knifsend, California State University, Sacramento

Jaana Juvonen, University of California, Los Angeles.

REFERENCES

- Aboud FE (1988). Children and prejudice. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ (1982). The features and effects of friendship in early adolescence. Child Development, 53, 1447–1460. doi: 10.2307/1130071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, Jones LC, & Lobliner DB (1997). Social categorization and the formation of intergroup attitudes. Child Development, 68, 530–543. doi: 10.2307/1131676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, & Liben LS (1992). Cognitive mechanisms in children’s gender stereotyping: Theoretical and educational implications of a cognitive-based intervention. Child Development, 63, 1351–1363. doi: 10.2307/1131561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogardus ES (1933). A social distance scale. Sociology and Social Research, 17, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, & Pierce KP (2005). Social identity complexity and outgroup tolerance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 428–437. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KT, Brown TN, Jackson JS, Sellers RM, & Manuel WJ (2003). Teammates on and off the field? Contact with Black teammates and the racial attitudes of White student athletes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 1379–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.15591816.2003.tb01954.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, & Evans WP (2002). Extracurricular activity and ethnicity: Creating greater school connection among diverse student populations. Urban Education, 37, 41–58. doi: 10.1177/0042085902371004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, & Raudenbush SW (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, & Furman W (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58, 1101–1113. doi: 10.2307/1130550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education (2011). DataQuest [Data file and code book]. Retrieved from http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/onJune21,2012.

- Clark ML, & Ayers M (1992). Friendship similarity during early adolescence: Gender and racial patterns. Journal of Psychology, 126, 393–405. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1992.10543372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotfelter CT (2002). Interracial contact in high school extracurricular activities. Urban Review, 34, 25–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1014493127609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denault A, & Poulin F (2016). What adolescents experience in organized activities: Profiles of individual and social experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 42, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2015.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, & Carey S (2011). Consequences of “minimal” group affiliations in children. Child Development, 82, 793–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin JB, Larson R, & Hansen D (2003). Adolescents’ accounts of growth experiences in youth activities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 17–26. doi: 10.1023/A:1021076222321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feddes AR, Noack P, & Rutland A (2009). Direct and extended friendship effects on minority and majority children’s interethnic attitudes: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 80, 377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, & Eccles JS (2006). Extracurricular involvement and adolescent adjustment: Impact of duration, number of activities, and breadth of participation. Applied Developmental Science, 10, 132–146. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1003_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, & Simpkins SD (2013). Organized outof-school activities and peer relationships: Theoretical perspectives and previous research In Fredricks JA & Simpkins SD (Eds.), Organized out-of-school activities: Settings for peer relationships. (pp. 1–17). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, & Aber JL (2006). The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 42, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, & Dovidio JF (2000). Reducing intergroup bias: The common ingroup identity model. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JM, & Charmaraman L (2009). Race, context, and privilege: White adolescents’ explanations of racial-ethnic centrality. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 139–152. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9330-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JV, Brown BB, & Heck DJ (2005). Bridging the ethnic divide: Student and school characteristics in African American, Asian-Descent, Latino, and White adolescents’ cross-ethnic friend nominations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 21–46. doi: 10.1111/j.15327795.2005.00085.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DM, & Larson RW (2007). Amplifiers of developmental and negative experiences in organized activities: Dosage, motivation, lead roles, and adultyouth ratios. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28, 360–374. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Houlette MA, Gaertner SL, Johnson KM, Banker BS, Riek BM, & Dovidio JF (2004). Developing a more inclusive social identity: An elementary school intervention. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 35–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00098.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PE (2004). False consensus in social context: Differential projection and perceived social distance. British Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 417–429. doi: 10.1348/0144666042038015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB (1978). Similarity in real-life adolescent friendship pairs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 306–312. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.36.3.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knifsend CA, & Juvonen J (2013). The role of social identity complexity in intergroup attitudes among young adolescents. Social Development, 22, 623–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00672.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knifsend CA, & Juvonen J (2014). Social identity complexity, cross-ethnic friendships, and intergroup attitudes in urban middle schools. Child Development, 85, 709–721. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, & MacKinnon DP (2001). Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36, 249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin S, Van Laar C, & Sidanius J (2003). The effects of ingroup and outgroup friendships on ethnic attitudes in college: A longitudinal study. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 6, 76–92. doi: 10.1177/1368430203006001013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV (1988). Homogeneity in confiding relations. Social Networks, 10, 57–76. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(88)90010-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, & Cook JM (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KP, Brewer MB, & Arbuckle NL (2009). Social identity complexity: Its correlates and antecedents. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 12, 79–94. doi: 10.1177/1368430208098778 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J (2001). Race, school integration, and friendship segregation in America. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 679–716. doi: 10.1086/338954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nahemow L, & Lawton MP (1975). Similarly and propinquity in friendship formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 205–213. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.32.2.205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, & Bagwell CL (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 306–347. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes J (1995). Two cities’ tracking and within-school segregation. Teachers College Record, 96, 681–690. [Google Scholar]

- Patchen M (1982). African American–Caucasian contact in schools: Its social and academic effects. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Selig JP (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6, 77–98. doi: 10.1016/0272-7757(95)00025-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DI, Argys LM, & Brewer DJ (1996). Tracking in the United States: Descriptive statistics from NELS. Economics of Education Review, 15, 83–89. doi: 10.1016/0272-7757(95)00025-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roccas S, & Brewer MB (2002). Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 88–106. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LO, Scott MA, & Way N (2015). Racial and gender identity among Black adolescent males: An intersectionality perspective. Child Development, 86, 407–424. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, & Petty RE (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5/6, 359–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer DR, Simpkins SD, Vest AE, & Price CD (2011). The contribution of extracurricular activities to adolescent friendships: New insights through social network analysis. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1141–1152. doi: 10.1037/a0024091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid K, Hewstone M, & Al Ramiah A (2013). Neighborhood diversity and social identity complexity: Implications for intergroup relations. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 135–142. doi: 10.1177/1948550612446972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid K, Hewstone M, & Tausch N (2014). Secondary transfer effects of intergroup contact via social identity complexity. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53, 443–462. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid K, Hewstone M, Tausch N, Cairns E, & Hughes J (2009). Antecedents and consequences of social identity complexity: Intergroup contact, distinctiveness threat, and outgroup attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1085–1098. doi: 10.1177/0146167209337037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, & Preacher KJ (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software]. Retrieved July 11, 2016, from http://quantpsy.org/

- Simpkins SD, O’Donnell M, Delgado MY, & Becnel JN (2011). Latino adolescents’ participation in extracurricular activities: How important are family resources and cultural orientation? Applied Developmental Science, 15, 37–50. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.538618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EH (1949). Measurement of diversity. Nature, 163(688). doi: 10.1038/163688a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanti C, Stukas AA, Halloran MJ, & Foddy M (2011). Social identity change: Shifts in social identity during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormala ZL, Petty RE, & Brinol P (2002). Ease of retrieval effects in persuasion: A self-validation analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1700–1712. doi: 10.1177/014616702237651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RN, Hewstone M, Voci A, Paolini S, & Christ O (2007). Reducing prejudice via direct and extended cross-group friendship. European Review of Social Psychology, 18, 212–255. doi: 10.1080/10463280701680297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, Larson RW, Mahoney JL, & Watts TW (2015). Children’s organized activities In Bornstein MH, Leventhal T, & Lerner R (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 4, 7th ed., pp. 305–344). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins N, Larson R, & Sullivan P (2007). Learning to bridge difference: Community youth programs as contexts for developing multicultural competencies. American Behavioral Scientist, 51, 380–402. doi: 10.1177/0002764207306066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YC (2000). Multiple imputation for missing data: Concepts and new development. In Proceedings of the twenty-fifth annual SAS users group international conference (Paper 267) Cary, NC: SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ, & Preacher KJ (2009). Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 695–719. doi: 10.1177/1094428108327450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, & Chen Q (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]