Abstract

Application of exogenous products, such as creams, to the skin can result in subclinical changes in selected epidermal functions such as transepidermal water loss (TEWL), hydration, redness, and pH; these changes may lead to or contribute to irritation. Changes in skin surface inflammatory factors may provide further insight into this potential for irritation. The objective of this study was to evaluate the changes in epidermal properties and inflammatory mediators after four days of topical application of two different polymers formulated in cosmetic creams. Ten healthy volunteers (mean ± SD age: 20.0 ± 2.4 years) completed the study. TEWL, color, and pH were not significantly different after repeated application of these polymers. Hydration was significantly lower at sites treated with polymer A after 5 days. Significant increases in IL-1α, IL-1RA, and IL-1β were observed post-cream application at sites treated with polymer A. This is the first study to apply noninvasive measurements to quantify subclinical changes in epidermal properties and inflammatory mediator expression before and after the application of a cosmetic product, which will allow for a more enhanced safety profile to be achieved.

Keywords: epidermis, inflammation, irritation, cosmetic, topical, transepidermal water loss, hydration, cytokine, chemokine

1. Introduction

The topical application of creams can influence several epidermal functions, such as transepidermal water loss (TEWL), hydration, color, and skin pH[1, 2]. Monitoring changes in these factors may shed light on a product’s potential for irritation and effects on the epidermal barrier function. In addition to changes in these parameters, changes in skin surface inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines could further clarify the potential for irritation at a subclinical level that is not obvious to the naked eye. Changes in inflammatory markers occur within the epidermis upon irritation. In murine epidermis, mRNA levels of TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF increased after acute and chronic barrier disruption, indicating that cytokine production may be stimulated by a change in barrier function[3]. Similarly, in other animal models, barrier function disruption has been shown to increase epidermal cytokine levels of TNFα, IL-1α, and IL-6[3–5]. Furthermore, an increase in mRNA levels of TNFα, IL-8 IL-10, and INFγ after tape stripping was observed in human volunteers[6].

One of the challenges with preclinical formulation and development of cosmetic creams is that these epidermal properties and changes in inflammatory profiles cannot be observed by the naked eye. The evaluation of changes in the skin after application of an exogenous product, such as a cosmetic cream, allows for a more complete understanding of the safety and efficacy of the product. There are a number of models available for examining the effect of cosmetic products on the skin, including in vitro and in vivo methods[7]. In vitro models, including skin culture models, are inadequate to accurately represent the complex interaction and signaling pathways between various structures of whole skin. Animal models also have several drawbacks including suboptimal representation of human skin structure, and in recent years, testing on animal has begun to fall out of favor with the public. In 2013, the European Union (EU) banned the use of animal models for testing cosmetic products sold in the EU, and the focus on cruelty-free product testing is also growing in the United States of America.

Typical methods for measuring cytokines in the skin are invasive, including skin biopsies, microdialysis, and tape stripping. Having a noninvasive method for determining changes pre- and post-application of a topical cream would be very beneficial as a screening tool in product development. Previous work has demonstrated that cytokines, chemokines, and inflammatory mediators can be extracted from the surface of the skin using simple skin wash techniques[8], allowing for noninvasive quantification of various skin inflammatory markers.

The objective of this study was to use non-invasive methods to assess skin surface properties and inflammatory markers after repeated topical applications of proprietary cosmetic polymers formulated by Ashland Specialty Ingredients, Inc. Noninvasive techniques were used to measure TEWL, hydration, redness, and skin pH before and after cream application. Epidermal inflammatory markers were also quantified at baseline (day 1) and on day 5, after product was applied for four days. To our knowledge this is the first study to utilize noninvasive measurements to quantify subclinical changes in epidermal properties and inflammatory marker expression following the use of a cosmetic product in order to obtain a more comprehensive safety profile of the product.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The creams and polymers evaluated in this study are proprietary products formulated by Ashland (Bridgewater, NJ). Triton™ X-100 was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). USP grade sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was obtained from Amresco LLC (Solon, OH). Protease and metalloproteinase inhibitors were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). The multiplex fluorescent bead-based immunoassay kit was obtained from EMD Millipore Corp (Billerica, MA). The Micro BCA protein assay kit was purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL).

2.2. Clinical study procedures

All clinical study procedures were approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board and followed guidelines outlined by the Declaration of Helsinki. Study procedures took place in the Clinical Research Unit at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment in the study. Healthy Caucasian volunteers between the ages of 18–30 were enrolled in the study. Subjects were in generally good health with no dermatological disorders or chronic medical conditions. Exclusion criteria included inability to give consent; severe general allergies (indoor, outdoor, or seasonal); any active medical conditions, including ongoing dermatological conditions; use of any medications or herbal supplements (vitamins and oral contraceptives were allowed); or pregnant/nursing.

2.3. Experimental procedures

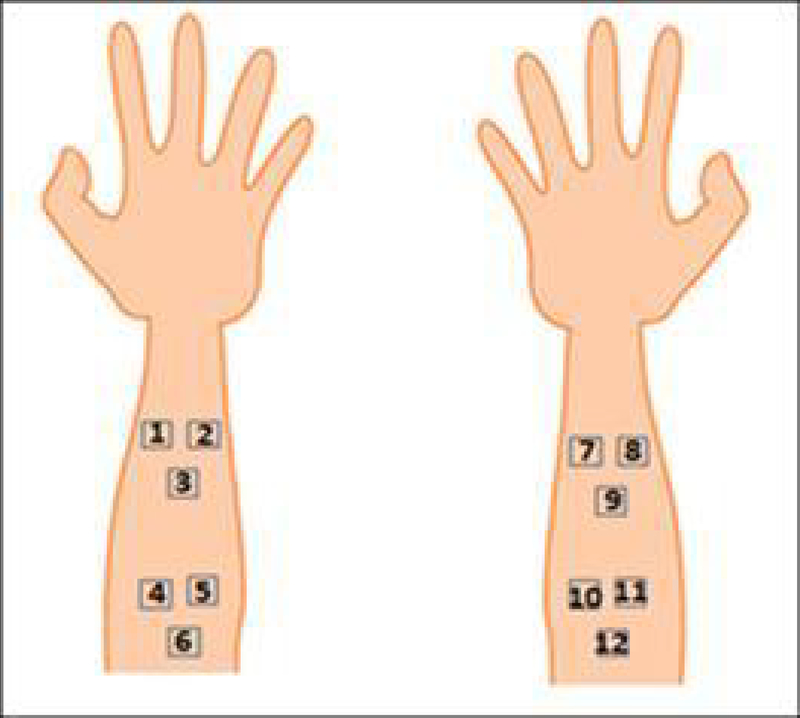

Four sites of 5×5 cm each were marked on the volar forearms, which served as the application area for each of the creams. Within each application area, three individual 2×2 cm sites were marked, and served as three independent measurement sites (Figure 1). Four conditions were examined: cream containing Polymer A, cream containing Polymer B, placebo cream, and no treatment. Table 1 describes the treatment applied to the sites.

Figure 1.

Location of the 12 measurement sites on the volar forearm

Table 1.

Descriptions of the treatments and corresponding measurement sites.

| Measurement sites | Treatment |

|---|---|

| 1–3 | Control (no cream) |

| 4–6 | Polymer A |

| 7–9 | Placebo |

| 10–12 | Polymer B |

Subjects came in daily for five consecutive days. On day 1, baseline measurements were made in triplicate at each of the measurement sites. TEWL was measured using an open chamber evaporimeter (Tewameter TM 300, Acaderm Inc., Menlo Park, CA). The probe was placed on the surface of the skin for approximately 15 seconds until the reading stabilized. The hydration of the skin was measured with a corneometer (Corneometer® CM 825, Acaderm Inc., Menlo Park, CA). The probe was placed on the surface of the skin for less than 5 seconds to make the measurement. The redness of the skin was measured with a tristimulus colorimeter (ChromaMeter CR-400, Konica Minolta, Ramsey, NJ). The probe was placed on the surface of the skin, and the a* value was recorded (this represents the red/green axis). The pH of the skin was measured with a pH skin probe (Skin-pH-Meter PH 905, Acaderm Inc., Menlo Park, CA). The probe was placed lightly on the skin for less than 5 seconds to make the measurement. After these measurements were made, the skin surface was gently swabbed in order to collect skin surface cytokines, chemokines, and other markers. For each study, 0.1% Triton™ X-100 solution in 1X PBS was prepared fresh and filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (EMD Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA). Gauze pads were soaked in 500 μl of the filtered solution. Using these pads, each site was swabbed systematically, five times in two directions. The gauze pads were placed into 0.22 μm filter centrifuge tubes (EMD Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA) and the buffer solution was extracted from the gauze swabs via centrifugation at 1200xg at 4°C for 10 minutes (Centrifuge 5804R, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The wash fluid was collected and treated with protease and metalloprotease inhibitors per manufacturer instructions. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. The swab procedure was only conducted on days 1 and 5.

After the skin was swabbed the subjects sat for 30 minutes, after which time 200 μL of each study cream was gently rubbed into its respective treatment area. The creams were re-applied to the subjects’ arms each day for the next three days (resulting in a total of four cream applications). On day 5, no cream was applied and the measurements and swab procedures were repeated at all measurement sites.

2.4. Skin wash fluid sample processing

The concentration of 12 analytes in the skin wash fluid were analyzed with a multiplexed fluorescent bead-based immunoassay according to manufacturer instructions, using a Luminex® 200 system (Luminex, Austin, TX). Table 2 describes the various classes of analytes analyzed. The amount of analyte was normalized to total soluble protein, which was determined using a BCA assay. Analytes are reported as pg analyte/μg total protein.

Table 2.

Class of analytes detected in skin wash fluid collected from subjects.

| Category | Specific analytes measured |

|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, GM-CSF, TNFα, TNFβ |

| Anti-inflammatory cytokines | IL-10, IL-13, IL-1RA |

| Chemokines | IL-8 |

| Interferons | INFγ |

2.5. Statistical analysis

The analysis focused on two main sets of models, both of which fall under the generalized linear mixed modeling (GLMM) framework. The first model set treats time and treatment (cream), along with their interaction, as main effects. This model allows us to test the significance of baseline (day 1) vs. day 5 measurements for each individual treatment (cream). Random effect intercepts were included for subject and site number nested within each subject. This utilizes all of the observations in the data set while accounting for correlation between observations from the same subject and sites within the same treatment group. The second model set treats site (cream) as a main effect so we can test the significance between the effects of the different creams. Random effects for subject and time point (baseline vs. day 5) nested within the subject were included to still account for time.

For each outcome, the two main models were fit controlling for demographic information, including sex, age, height, weight, and BMI. Using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) to compare between models with the same outcome[9], the best subset of control variables was identified and estimates were generated using the best fit models. The AIC was also used to determine the proper link function for each outcome (identity link for normal distribution, log link for right-skewed distribution). Since each model includes multiple comparisons between time or site (cream), the Bonferroni correction was used to lower the threshold of significance in order to minimize the likelihood of committing a type 1 error. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Ten healthy Caucasian subjects completed the study. Subjects had a mean (± SD) age of 20.0 ± 2.4 years and a mean BMI of 22.1 ± 3.1 kg/m2. Demographics of the subjects are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographics for subjects completing the study. All values are reported as mean ± SD (range).

| Sex | Females: 6 |

|---|---|

| Males: 4 | |

| Age, years (range) | 20.0 ± 2.4 (18 – 25) |

| Height, cm (range) | 174.4 ± 10.5 (151.6 – 191.6) |

| Weight, kg (range) | 67.4 ± 12.4 (47.0 – 85.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (range) | 22.1 ± 3.1 (17.3 – 26.5) |

3.2. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL)

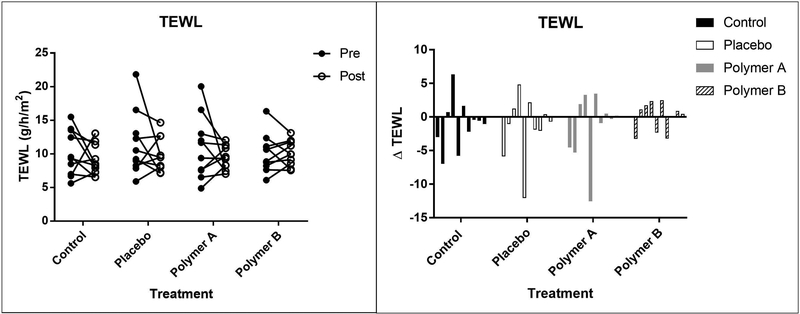

The mean (± SD) TEWL values decreased from baseline (day 1) to day 5 for all treatment groups, with the exception of the polymer B treatment group. TEWL values were as follows (baseline values reported first): control: 10.2 ± 3.4 g•m−2•h−1 vs. 9.1 ± 2.3 g•m−2•h−1; placebo: 11.4 ± 4.7 g•m−2•h−1 vs. 9.9 ± 2.6 g•m2•h−1; polymer A: 10.9 ± 4.7 g•m−2•h−1 vs. 9.5 ± 1.8 g•m−2•h−1; polymer B: 10.1 ± 2.9 g•m−2•h−1 vs. 10.1 ± 1.9 g•m−2•h-1. There was no significant difference between baseline and post-cream application for any of the treatment groups (p>0.05). Treatment group was found to have a significant effect on TEWL. The polymer B group overall had significantly higher TEWL measurements compared to the no cream group when accounting for time (p=0.0009). TEWL values for the control group were overall significantly lower compared to placebo cream group after accounting for time (p<0.0001). TEWL measurements for each subject are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Mean TEWL values at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported as g/h/m2 (left panel). Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. The lines connect pre- and post-treatment measurements for that subject. Right panel: Change in TEWL values from baseline to day 5. Each bar represents a different subject.

3.3. Hydration

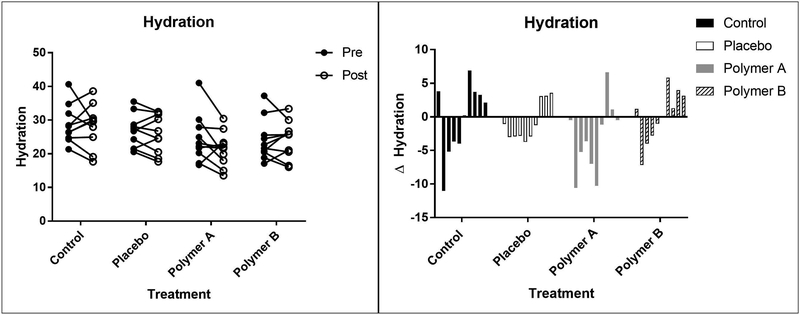

Mean (±SD) measurements of hydration (in arbitrary units, AU) from baseline (day 1) to day 5 were as follows: control: 28.7 ± 5.7 AU vs. 28.3 ± 6.4 AU; placebo: 26.7 ± 5.0 AU vs. 25.9 ± 5.7 AU; polymer A: 24.5 ± 7.2 AU vs. 21.4 ± 5.2 AU; polymer B: 24.1 ± 6.2 AU vs. 24.1 ± 5.6 AU. The decrease in hydration from baseline to day 5 was significant for the polymer A group (p=0.0027). Treatment group was found to have a significant effect on hydration (p<0.0001). The polymer A group and polymer B group overall had significantly lower hydration measurements than the control group (p<0.0001 for both polymers) and the placebo cream group (p<0.0001 for both polymers). The magnitude of change between the baseline and post-cream application was consistent across the treatment groups. Hydration values for each subject are represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3:

Mean hydration measurements at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported as arbitrary units (left panel). Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. The lines connect pre- and post-treatment measurements for that subject. Right panel: Change in hydration values from baseline to day 5. Each bar represents a different subject.

3.4. Color

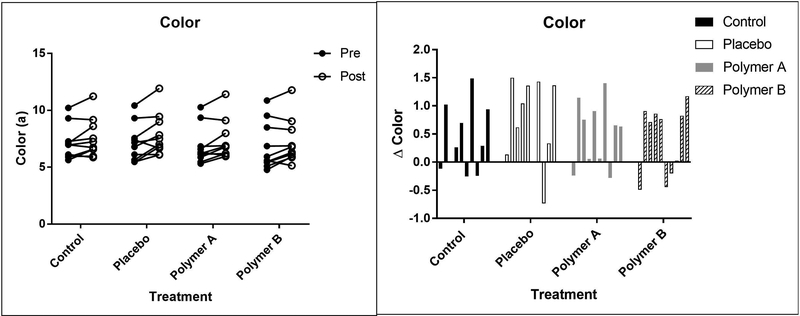

The mean (±SD) a* value was slightly higher post-treatment from baseline (Figure 4). From baseline (day 1) to day 5, redness (measured in AU) was as follows: control group: 7.1 ± 1.5 AU vs 7.6 ± 1.7 AU; placebo group: 7.1 ± 1.7 AU vs 7.8 ± 1.8 AU; polymer A group: 6.8 ± 1.6 AU vs 7.3 ± 1.7 AU; polymer B group: 6.8 ± 2.1 AU vs 7.2 ± 2.0 AU. Measurements of redness were significantly higher post-cream application for the placebo group (p=0.0003), though the difference in redness for all of the treatment groups was not clinically significant and could not be seen to the naked eye. Treatment group was found to have a significant effect on color (p = 0.0021). The polymer A and polymer B groups were significantly less red overall compared to the control group (p<0.005 for both polymers) and the placebo cream group (p<0.0001 for both polymers).

Figure 4:

Mean color (redness) values at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported as arbitrary units known as a* (left panel). Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. The lines connect pre- and post-treatment measurements for that subject. Right panel: Change in a* values from baseline to day 5. Each bar represents a different subject.

3.5. pH

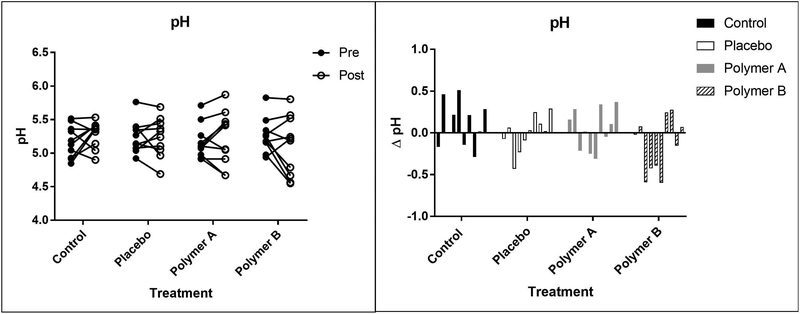

The pH values for each subject are represented in Figure 5. Mean (±SD) pH values were similar across time and treatment groups. From baseline (day 1) to day 5, pH measurements were as follows: control group: 5.2 ± 0.2 vs 5.3 ± 0.2; placebo group: 5.2 ± 0.2 vs 5.2 ± 0.3; polymer A group: 5.2 ± 0.3 vs 5.2 ± 0.4; polymer B group: 5.3 ± 0.3 vs 5.1 ± 0.4. pH measurements were not significantly different overall between baseline and post-cream application (p=0.9915). Treatment group did not have a significant effect on skin pH (p=0.4086). Although time and treatment group were not significant, the interaction between them was significant (p=0.0097). The mean difference between baseline and post-cream application for the control group was significantly greater than the mean difference between the baseline and post-cream application for the polymer B group (p=0.0013).

Figure 5:

Mean pH values at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported as pH units (left panel). Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. The lines connect pre- and post-treatment measurements for that subject. Right panel: Change in pH values from baseline. Each bar represents a different subject.

3.6. Skin surface analytes

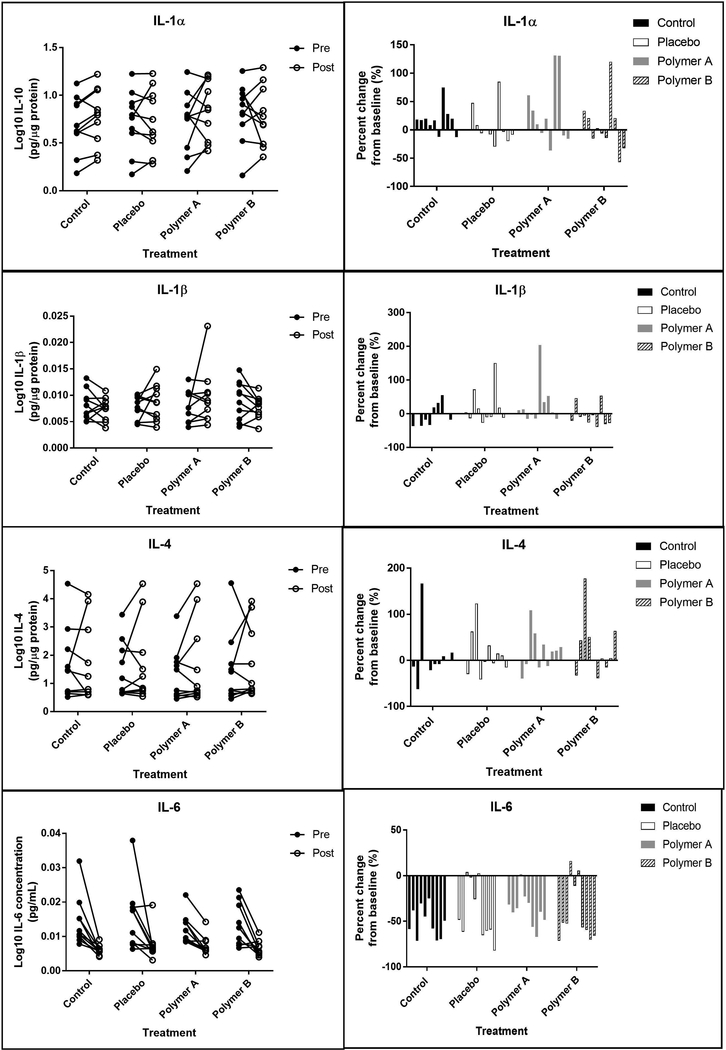

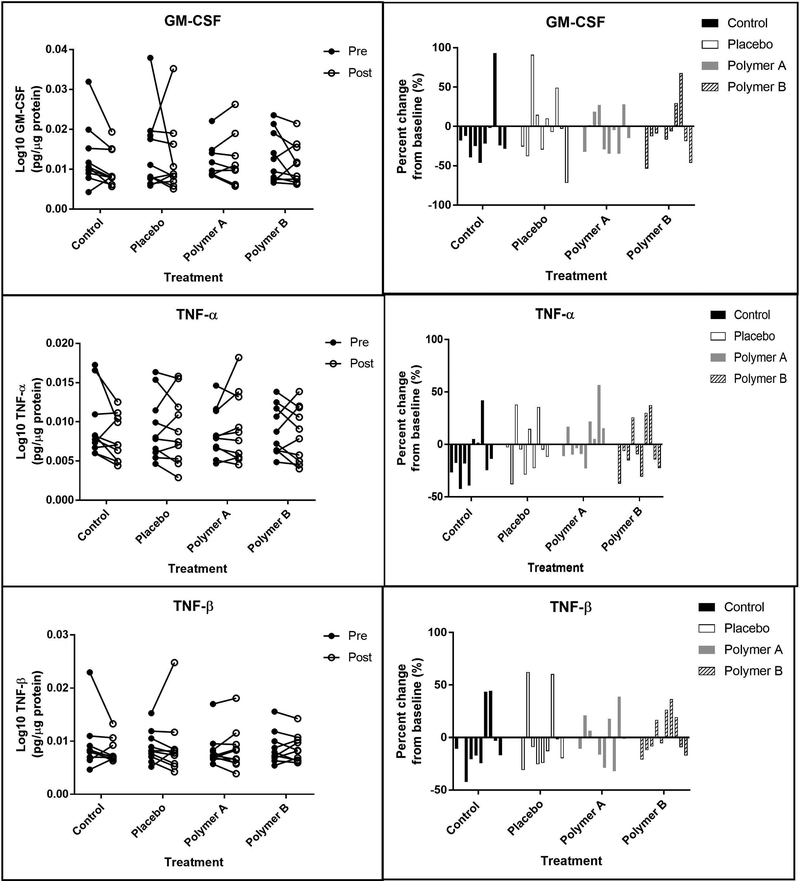

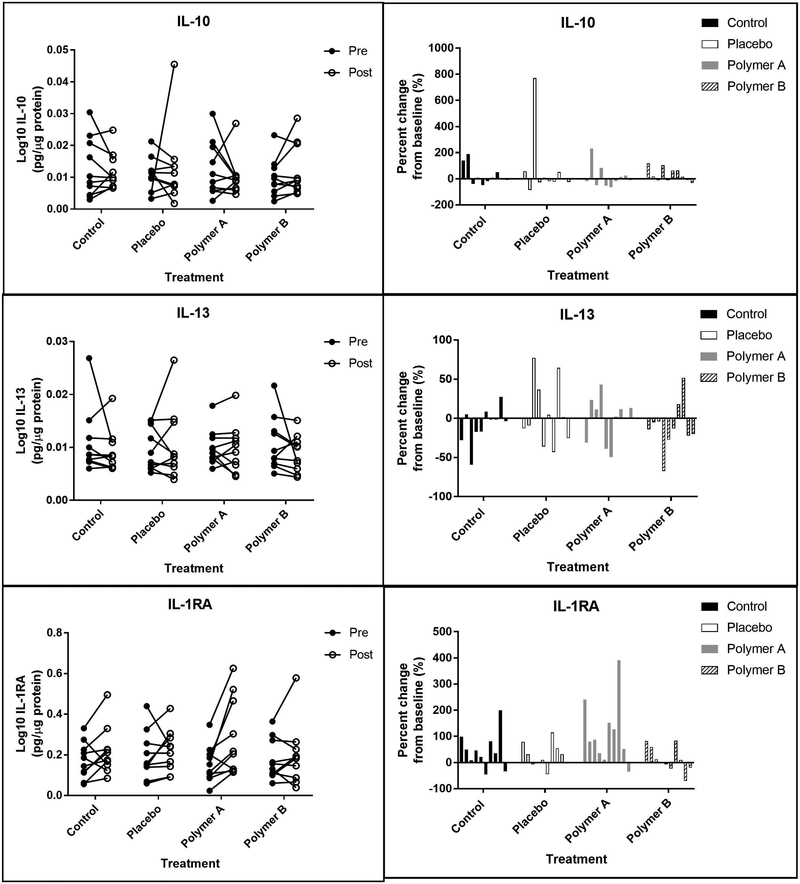

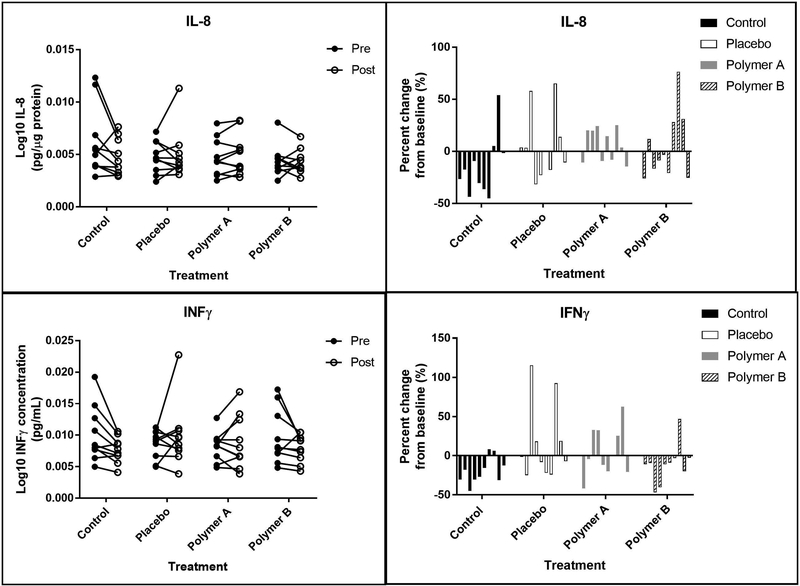

Figures 6,7,8,9 shows the 12 skin surface inflammatory mediators that were evaluated in this study. No pairwise comparisons for any of the treatment groups had significant p-values at the Bonferroni corrected level of significance. IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1RA were significantly higher on day 5 for the polymer A treatment group (p<0.005 for each). IL-1α and IL-1RA were significantly higher on day 5 for the control treatment group (p<0.001).

Figure 6:

Pro-inflammatory interleukins. Left panels: Concentrations of interleukins (IL) 1α, 1β, 4, and 6 at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and at day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported in pg analyte/μg total soluble protein. Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. Right panels: Normalized % change from baseline. The % change was calculated for each mediator using the equation: % change = (post-baseline) baseline x 100. Each bar represents an individual subject (n=10) and that subject’s change from baseline for each condition.

Figure 7:

Pro-inflammatory mediators. Left panels: Concentrations of GM-CSF, TNF-α and TNF-β at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and at day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported in pg analyte/μg total soluble protein. Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. Right panels: Normalized % change from baseline. The % change was calculated for each mediator using the equation: % change = (post-baseline) baseline x 100. Each bar represents an individual subject (n=10) and that subject’s change from baseline for each condition.

Figure 8:

Anti-inflammatory interleukins. Left panels: Concentrations of interleukins (IL) 10, 13, and 1RA at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and at day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported in pg analyte/μg total soluble protein. Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. Right panels: Normalized % change from baseline. The % change was calculated for each mediator using the equation: % change = (post-baseline) baseline x 100. Each bar represents an individual subject (n=10) and that subject’s change from baseline for each condition.

Figure 9:

Chemokines and interferons. Left panels: Concentrations of interleukins (IL) 8 and INFλ at baseline (“pre”, closed circles) and at day 5 (“post”, open circles), reported in pg analyte/μg total soluble protein. Each set of connected circles represents a different subject, with a different color for each subject. Right panels: Normalized % change from baseline. The % change was calculated for each mediator using the equation: % change = (post-baseline) baseline x 100. Each bar represents an individual subject (n=10) and that subject’s change from baseline for each condition.

The following skin surface analytes were not significantly different between baseline (day 1) and day 5 when normalized to total protein content in the wash fluid for any of the treatment groups: GM-CSF, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, INFy, TNFα, and TNFβ. Treatment group did not significantly affect the following skin surface analytes: GM-CSF, IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, INFy, TNFα, and TNFβ.

Treatment group had a significant effect on IL-1α concentrations, with the polymer B treatment group having an overall significantly higher IL-1α concentration compared to the no cream group (p=0.0014). Polymer A and polymer B treatment groups had overall significantly higher IL-1α concentrations compared to the placebo cream group after accounting for time (p<0.01). Treatment group also had a significant effect on IL-8 concentrations, with the polymer B group having an overall significantly lower IL-8 concentration compared to the control group when taking time into account (p=0.0004).

The interaction between time and treatment group was evaluated to determine if the change in analyte concentration between baseline and post-cream application was consistent across the treatment groups. This interaction was found to be significant for four analytes: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1RA, and INFy. For IL-1α, the mean ratio for the polymer A change was 57% greater than that for the polymer B change (p=0.0044). Additionally, the mean ratio for the change at control sites was 67% greater than that for the polymer B (p=0.0015). For IL-1β, the mean ratio for the placebo change is 34% greater than that of the polymer B change (p=0.0043); the mean ratio for the polymer A change was 43% greater than that of the polymer B change (p=0.0006). For IL-1RA, the mean ratio for the polymer A change was 82% greater than that for the placebo cream and 116% greater than that of polymer B (p<0.005 for both comparisons). Finally, the mean ratio for the placebo cream changes in INFy was 35% greater than that for the polymer B creams (p=0.0025).

4. Discussion

Commercial topical skin care products (creams, gels, ointments, etc.) are designed to address a wide variety of cosmetic indications, including skin protection, reduction of fine lines and wrinkles, and reversing signs of sun damage. It is important that topically applied products do not induce changes in the skin’s epidermal barrier properties or induce expression of inflammatory modulators (cytokines or chemokines). Historically, the methods for evaluating skin irritation have relied upon subjective visual assessment of redness, lesions, or dryness. These subjective analyses do not permit quantification of subclinical processes or irritation, and alterations in epidermal characteristics cannot be detected before changes are seen by the naked eye.

In this small pilot study, skin on the forearm of healthy human volunteers was treated with creams containing proprietary polymers developed by Ashland Specialty Ingredients. As high molecular weight polymers are not expected to penetrate the stratum corneum, their effects on the epidermis would be due to physical changes in the properties of the stratum corneum, and not as a result of conventional bioactive cosmetic ingredients. Noninvasive techniques were used to evaluate surrogate markers of epidermal barrier function, including TEWL, hydration, colorimetry (redness), and pH. A noninvasive skin swab technique was used to collect cytokines, chemokines, and other known mediators of skin inflammation. This is the first study to evaluate barrier function and skin surface inflammatory analytes at a subclinical level for skin treated with cosmetic products.

4.1. Epidermal barrier function

The barrier function of the skin prevents both the influx of exogenous compounds and the efflux of water and electrolytes. Therefore, a competent skin barrier is essential for maintaining homeostasis and preventing skin irritation. Intact skin prevents excessive water loss to the external environment, which in turn correlates with a low TEWL measurement. TEWL values for intact skin of the forearms of Caucasian individuals range between 4 to 9 g•m−2•h−1, although these values can be influenced by a wide range of factors [10, 11],[12]. Increases in TEWL measurements are indicative of deficiencies in the skin barrier function, and increases of 2–3x baseline have been reported following exposure to irritants[13]. In this study, there were no significant changes in TEWL observed from baseline to post-cream application in any treatment group (p>0.05), indicating that none of the treatments disrupted barrier function. This is particularly important because disruption of the barrier could lead to downstream problems with infection, irritation, or absorption of exogenous substances. Significantly higher TEWL measurements were observed overall for the placebo group and polymer B group as compared to the control group when clustering observations by time point (p<0.001). The change from baseline was not significantly different between the treatment groups (p>0.05). In other words, the higher TEWL values observed for the placebo and polymer B groups were likely due to external factors besides the application of the cream. One potential explanation is that both the placebo cream and the polymer B cream were applied to the right forearm, while the no cream control condition was located on the left forearm (Figure 1). TEWL measurements have been shown to be increased on the dominant forearm (most commonly the right forearm) compared to the non-dominant forearm[14], which may be due to repetitive movements with the dominant hand that could affect the stratum corneum.

Adequate hydration of the stratum corneum is important for both barrier function and aesthetic purposes. Formulations that lead to drying of the skin could cause irritation and poor acceptance by users. Overall, the polymer A treatment group had significantly lower hydration after cream application compared to baseline measurements (p=0.0027). On a subject level, the hydration measurements decreased for all treatment groups from baseline to post-cream application in half of the subjects, while the hydration measurements increased for all treatment groups from baseline to post-cream application in 3 of the 10 subjects. Interestingly, the subjects with similar trends regarding change in hydration status were evaluated in the clinic within a few weeks of one another. That is, the subjects with a decrease in hydration status were all scheduled within a three-week timeframe, and the subjects with an increase in hydration status were scheduled within a different two-week timeframe. Changes in the stratum corneum can be affected by external temperature and humidity[15], and room conditions where the study visits took place have the potential to influence hydration measurements in as little as 30 minutes[16]. Therefore, these trends may be the result of environmental conditions at the time of the subject’s visits. Though the hydration status of the skin decreased for many subjects, the change from baseline was not significantly different for the control, placebo, or polymer B groups (p>0.05); change from baseline was significant for polymer A (p=0.0027). There were no visual differences at the sites of cream application for any of the subjects, and subjects did not report any adverse reactions, including dryness or itching, indicating that these changes are likely not clinically relevant.

Change in erythema from baseline (Δa*) is also an important surrogate marker for assessing skin irritation. A known skin irritant, sodium lauryl sulfate, can produce a Δa* value of up to 4.7 in humans[17]. The a* measurement was increased slightly at day 5 in this study, though the change from baseline was not significantly different between any of the treatment groups (p>0.05). Additionally, no single Δa* surpassed 1.5 (Figure 4); thus, Δa* in all conditions tested were well below values observed with known irritants and are not expected to be clinically significant. The slight increase in redness observed for each of treatment group was likely due to transient external factors, such as temperature of the skin, room, or outdoors, and skin type of the individual.

Under normal conditions, the skin is mildly acidic at pH ~5.5. Even small changes in pH can significantly alter skin barrier function and repair by affecting enzymes required for barrier maintenance and repair. Alkaline cutaneous pH topical products also negatively affect the stratum corneum buffering system and can lead to irritation[18]. Thus, change in pH related to topical application of cosmetic products could potentially lead to a very counterproductive effect and result in irritation. There was no significant change in pH between baseline and post-cream application measurements or between the different treatments (p>0.05) in this study. The change from baseline was significantly greater for the control group compared to the polymer B group (p=0.0013); however, this is likely to not be clinically significant, as the pH values at baseline and post-cream application are within normal range[12, 19].

4.2. Markers of inflammation

Cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators are important in mediating allergic, irritation, and inflammatory processes. It is important that these highly regulated pathways are not disrupted by topical cosmetic products. Many of the inflammatory mediators examined in this pilot study have important roles in skin homeostasis, allergic skin inflammation, and inflammatory pathways following skin irritation[20]. The non-normalized data from the current study were in good agreement with previous work of this type, particularly when comparing subjects of a similar age group [8]. Some of the cytokines known to be involved in the response to skin irritation include IL-1α, IL-1RA, IL-1β, IL-4, GMCSF, IFNγ, and TNFα (generally, increases in these cytokines are observed after irritation). In our study, only four of the 12 mediators measured were significantly different from baseline (day 1) to day 5 when normalized to total protein content in the wash fluid: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1RA, and IL-10.

IL-1α and IL-1RA are both constitutively expressed in the skin under basal conditions. Increases in IL-1α are expected after damage or irritation to the skin[21, 22]. The inflammatory effects of IL-1α are counteracted by the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-1RA, and thus the ratio of IL-1RA/IL-1α is also important. In cases of repeated irritation, the ratio may increase, whereas a change may not be observed after a single irritation[13].

In the current study, IL-1α concentrations were significantly higher on day 5 for the control group and polymer A group (p<0.001); however, the change from baseline was not significantly different between these two groups (p=0.7252). That is, the magnitude of change between baseline and post-cream application was comparable for the control group and polymer A treatment group. IL-1RA concentrations also were significantly higher at day 5 compared to baseline for the control group and polymer A group (p<0.001). The change in IL-1RA concentrations from baseline for the polymer A treatment group was not significantly greater than the change from baseline for the control group (p=0.1250). On the other hand, the change from baseline for the polymer B treatment group was significantly different than the control group for IL-1α concentrations (p=0.0015), and IL-1RA concentrations (p=0.0223).

For the majority of subjects, a slight increase in the mean IL-1RA/IL-1α ratio was observed when comparing baseline vs. post-application: control: 0.628 ± 0.142 vs 0.661 ± 0.116; placebo: 0.645 ± 0.167 vs 0.667 ± 0.159; polymer A: 0.583 ± 0.123 vs 0.668 ± 0.148; polymer B: 0.599 ± 0.135 vs 0.601 ± 0.143). The mean IL-1RA/IL-1α change from baseline was the greatest for the polymer A group (difference of 0.085) and the least for the polymer B group (difference of 0.002). Overall, this shift was observed for all treatment groups, including the control group, and this increase was small in comparison to the threefold increase observed after repeated irritation with a known irritant[13].

IL-1β concentrations were significantly higher at day 5 for the polymer A group (p=0.0031). This may be the result of an outlier, as a single subject experienced a 200% increase in IL-1β at the polymer A sites, while the remaining subjects had much less dramatic changes (<50% change) in IL-1β expression (Figure 6). Finally, the change from baseline for the polymer B group was significantly smaller than that of the placebo group for IL-1β and INFγ (p<0.005), although there was no significant difference between baseline and post-cream application for either of these cytokines for the polymer B treatment group (p>0.0338). Since both of these mediators have been known to increase after barrier disruption[3, 6], minimizing changes from baseline, as seen with polymer B, is ideal

4.3. Applications for other topical products

Topical products have previously been evaluated for irritation potential through subjective assessments based on the visual appearance and feeling of the skin once the product is applied. While these attributes are important to consider, they do not comprehensively describe how the product affects the skin on a variety of levels. Changes in barrier function or inflammatory processes that cannot be visually observed would provide further insight to the safety and efficacy of the product. The methods used in this study allow for these subclinical changes to be quantified, which provides an in-depth level of screening not currently completed for cosmetic products. The methods used in this study are all noninvasive, quick, and can be easily applied in a clinical setting.

Alterations in TEWL, pH, or inflammatory mediators may be indicative of irritation, but would not be detected through the current subjective methods of evaluation. Therefore, assessing these changes could increase the safety profile of the product in question. In this study, hydration appeared to follow similar trends in each of the treatment groups within each individual subject, but the trends between subjects varied (which is not unexpected). As previously mentioned, this may be due to external factors beyond what can be reasonably managed in a small pilot study. Additionally, subjects did not express concerns about the dryness of their skin throughout the study, indicating that while the skin was objectively drier, it did not influence the subject’s overall perception of hydration. Therefore, hydration may not be a primary endpoint of interest when evaluating irritation potential on this subclinical level. Ultimately, the methods of evaluation will vary depending on the product of interest and its intended use. The ease and rapidness of these measurements allow these methods to be translatable to a wide range of products and populations.

5. Limitations

Some limitations exist in this work. First, this was a small study with a small number of participants. This limitation is somewhat offset by the experimental design in which each treatment condition contained multiple measurement sites, and each of the epidermal properties were measured in triplicate at each measurement site. Overall this allowed for a large amount of data to be collected. Some factors were out of the control of the investigators, such as external temperature and humidity, which may influence some of the properties measured in this study, particularly hydration. Finally, the subjects enrolled in this study were young, healthy volunteers with no ongoing dermatological conditions. Therefore, caution must be exercised when interpreting these results, as these outcomes may not be as generalizable to other populations. For example, it has been previously shown that the presence and concentration of inflammatory factors are altered in different age groups. In particular, there appears to be a shift towards a pro-inflammatory state in elderly individuals[8], which may present a different potential for irritation than what was presented here. However, the evaluation of these creams in various populations is beyond the scope of the small pilot study. Rather, this study has shown the ability of evaluating these subclinical changes after product application, which may be used in future studies.

6. Conclusions

This study is the first to objectively and noninvasively quantify subclinical changes in epidermal barrier properties and inflammatory mediator presence after the application of cosmetic polymers. These methods can be applied in future studies to evaluate the potential for irritation beyond visual inspection for a range of cosmetic and topical products. Overall, these methods will provide noninvasive means for enhancing the safety profile of skin products.

7. Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was performed in the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54TR001356. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

8. References

- 1.Buraczewska I, Berne B, Lindberg M, Torma H, and Loden M, Changes in skin barrier function following long-term treatment with moisturizers, a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol, 2007. 156(3): p. 492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loden M, The clinical benefit of moisturizers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2005. 19(6): p. 672–688; quiz 686–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood LC, Jackson SM, Elias PM, Grunfeld C, and Feingold KR, Cutaneous barrier perturbation stimulates cytokine production in the epidermis of mice. J Clin Invest, 1992. 90(2): p. 482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood LC, Elias PM, Calhoun C, Tsai JC, Grunfeld C, and Feingold KR, Barrier disruption stimulates interleukin-1 alpha expression and release from a pre-formed pool in murine epidermis. J Invest Dermatol, 1996. 106(3): p. 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang XP, Schunck M, Kallen KJ, Neumann C, Trautwein C, Rose-John S, and Proksch E, The interleukin-6 cytokine system regulates epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis. J Invest Dermatol, 2004. 123(1): p. 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nickoloff BJ and Naidu Y, Perturbation of epidermal barrier function correlates with initiation of cytokine cascade in human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1994. 30(4): p. 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidgwick GP, McGeorge D, and Bayat A, Functional testing of topical skin formulations using an optimised ex vivo skin organ culture model. Arch Dermatol Res, 2016. 308(5): p. 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinn PM, Holdren GO, Westermeyer BA, Abuissa M, Fischer CL, Fairley JA, Brogden KA, and Brogden NK, Age-dependent variation in cytokines, chemokines, and biologic analytes rinsed from the surface of healthy human skin. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akaike H, A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1974. 19: p. 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kompaore F, Marty JP, and Dupont C, In vivo evaluation of the stratum corneum barrier function in blacks, Caucasians and Asians with two noninvasive methods. Skin Pharmacol, 1993. 6(3): p. 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimes P, Edison BL, Green BA, and Wildnauer RH, Evaluation of inherent differences between African American and white skin surface properties using subjective and objective measures. Cutis, 2004. 73(6): p. 392–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boer M, Duchnik E, Maleszka R, and Marchlewicz M, Structural and biophysical characteristics of human skin in maintaining proper epidermal barrier function. Postepy Dermatol Alergol, 2016. 33(1): p. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jongh CM, Lutter R, Verberk MM, and Kezic S, Differential cytokine expression in skin after single and repeated irritation by sodium lauryl sulphate. Exp Dermatol, 2007. 16(12): p. 1032–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treffel P, Panisset F, Faivre B, and Agache P, Hydration, transepidermal water loss, pH and skin surface parameters: correlations and variations between dominant and non-dominant forearms. Br J Dermatol, 1994. 130(3): p. 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black D, Del Pozo A, Lagarde JM, and Gall Y, Seasonal variability in the biophysical properties of stratum corneum from different anatomical sites. Skin Res Technol, 2000. 6(2): p. 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cravello B and Ferri A, Relationships between skin properties and environmental parameters. Skin Res Technol, 2008. 14(2): p. 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnetz E, Diepgen TL, Elsner P, Frosch PJ, Klotz AJ, Kresken J, Kuss O, Merk H, Schwanitz HJ, Wigger-Alberti W, and Fartasch M, Multicentre study for the development of an in vivo model to evaluate the influence of topical formulations on irritation. Contact Dermatitis, 2000. 42(6): p. 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bornkessel A, Flach M, Arens-Corell M, Elsner P, and Fluhr JW, Functional assessment of a washing emulsion for sensitive skin: mild impairment of stratum corneum hydration, pH, barrier function, lipid content, integrity and cohesion in a controlled washing test. Skin Res Technol, 2005. 11(1): p. 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berardesca E, Pirot F, Singh M, and Maibach H, Differences in stratum corneum pH gradient when comparing white Caucasian and black African-American skin. Br J Dermatol, 1998. 139(5): p. 855–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sehra S, Yao Y, Howell MD, Nguyen ET, Kansas GS, Leung DY, Travers JB, and Kaplan MH, IL-4 regulates skin homeostasis and the predisposition toward allergic skin inflammation. J Immunol, 2010. 184(6): p. 3186–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkins MA, Osterhues MA, Farage MA, and Robinson MK, A noninvasive method to assess skin irritation and compromised skin conditions using simple tape adsorption of molecular markers of inflammation. Skin Res Technol, 2001. 7(4): p. 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angelova-Fischer I, Becker V, Fischer TW, Zillikens D, Wigger-Alberti W, and Kezic S, Tandem repeated irritation in aged skin induces distinct barrier perturbation and cytokine profile in vivo. Br J Dermatol, 2012. 167(4): p. 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]