Summary

While certain medical societies have released guidelines on the use of social media, plastic surgery, with its inherent visual nature and potential for sensationalism, could benefit from increasing direction regarding the ethical use of social media. We hypothesized that while general platitudes for use exist in the literature, guidelines articulating the boundaries of professional use are nonspecific. Systematic searches of MEDLINE, Embase.com, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were completed on January 18, 2017. Searches consisted of a combination of MeSH terms and title and abstract keywords for social media and professionalism concepts. Additionally, we manually searched the three highest impact plastic surgery journals (ending in October 2017). Two authors screened all titles and abstracts. Studies related to clinical medicine, patient care, and the physician-patient relationship were included for full text review. Articles related to surgery merited final inclusion. The initial search strategy yielded 954 articles, with 27 selected for inclusion after final review. Our manual search yielded nine articles. Of the articles from the search strategy, ten were published in the urology literature, eight in general surgery, six in plastic surgery, three in orthopedic surgery, and one in vascular surgery. Key ethical themes emerged across specialties, although practical recommendations for professional social media behavior were notably absent. In conclusion, social media continues to be a domain with potential professional pitfalls. Appropriate use of social media must extend beyond obtaining consent, and we must adhere to a standard of professionalism far surpassing that of today's media culture.

Introduction

Social media has attained an undeniably significant influence within medicine. Not only does it provide means of networking at professional conferences and discussing the latest scientific papers with colleagues [1], surgeons also utilize social media for marketing and branding, educating the public, and communicating directly with patients [2]. Plastic surgeons have led the way in this regard, given the consumer-driven nature of the surgical services offered [2]. Importantly, 59-70% of plastic surgery patients stated in prior surveys that the Internet functions as a valuable resource for evaluating plastic surgeons and understanding potential surgical procedures [3]. Given the current cultural climate and the expectations of the public, almost 60% of surveyed plastic surgeons felt that social media engagement is inevitable and beneficial for the maintenance of a successful practice [4].

However, the prevalence of social media in the various surgical specialties should give us considerable pause. Breaches of patient confidentiality still occur, and these infractions are not without serious consequences [5]. Even more disquieting is the sensationalism that distinguishes the content of social media posts by a small percentage of plastic surgeons. Photographs and videos capturing sensitive anatomy and operative procedures in a sometimes casual manner render these posts potentially unprofessional and disrespectful, which violates the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) Code of Ethics' mandate to always use respectful language and images. While the Social Media Task Force was established by the ASPS in 2015 to promote responsible social media use, the ASPS Code of Ethics still does not provide specific guidance on social media. However, the Code of Ethics was written to be a fluid and timeless document, much like the Constitution. As such, terms like “electronic media” appear in the Code of Ethics, which necessarily includes the realm of social media, instead of referring to specific social media platforms. Furthermore, aside from enumerating social media's many benefits, the plastic surgery literature does not adequately address what constitutes both professional and ethical conduct on social media. As such, we hypothesized that the surgical literature would provide generalized maxims on the appropriate use of social media without specifically defining professional content.

To test our hypothesis we performed a rigorous review of the literature to assess published recommendations from all surgical specialties for the professional use of social media. Based upon our review of included articles, we discuss the potential implementation of society guidelines, as well as strategies for helping to equip plastic surgeons to use social media effectively, safely, and professionally.

Methods

We ran comprehensive literature searches in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, Embase.com, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on January 18, 2017. Each search consisted of a combination of controlled terms (MeSH in Ovid and Cochrane; EMTREE in Embase) and title and abstract keywords for the social media and professionalism concepts. A pre-identified set of five key articles were used to generate relevant search terms and to test the effectiveness of the searches. In order to minimize the possibility of missed studies, we supplemented the comprehensive database searches with a manual search of the three highest impact plastic surgery journals over a ten-month period (ending in October 2017). Duplicates were removed in Endnote X6. The reproducible searches for all databases are available at DOI:10.7302/Z2VH5M1H.

Two authors (KB & NB) independently screened all titles and abstracts in DistillerSR. For inclusion, studies had to relate to clinical medicine, direct patient care, and the physician-patient relationship. Studies meeting these criteria underwent full-text review. The same criteria were used for inclusion at this stage, with the addition that each study relates to social media, professionalism, and surgery. Disagreements at both stages were resolved through discussion. The screening questions and decision data are available at DOI: 10.7302/Z2VH5M1H.

Results

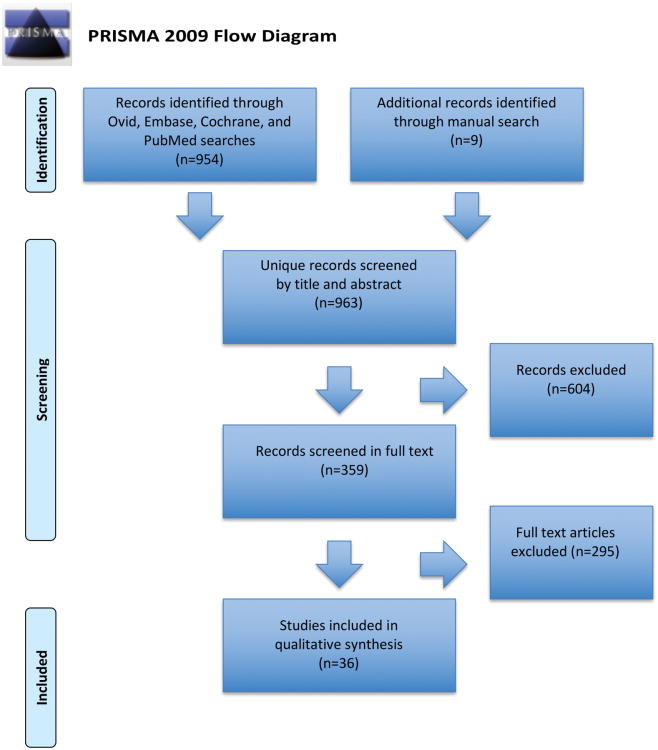

The search strategy yielded 954 articles (Figure 1). Title/abstract review was performed utilizing the three selected questions as mentioned in the methods section. After review and subsequent resolution of conflicts, 353 articles remained. After full text review and resolution of conflicts, 27 articles were selected for inclusion (Table 1). Nine articles were also included from manual review of articles published by plastic surgery journals with the three highest impact factors (Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgery, and Aesthetic Surgery Journal) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Prisma 2009 Flow Diagram. (from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Table 1. Summary of Articles Included in Literature Review.

| Reference | Surgical specialty discussed | Article Objectives | Journal | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landman et al., 2010 | General surgery | To assess use of SoMe by faculty and residents at one program and to present guidelines | Journal of Surgical Education | Understand institutional policies, educate faculty/residents on policies, appoint dept. rep to manage SoMe; monitor your online presence, understand privacy settings, remember audience, maintain boundaries, be aware of post permanence |

| Patel et al., 2011 | Plastic surgery | To discuss ethical issues when using SoMe for marketing | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Overlap between work and play can compromise patient-physician relationship |

| Wong and Gupta, 2011 | Plastic surgery | To compare traditional marketing methods with SoMe in plastic surgery | Aesthetic Surgery Journal | Communication with patients on SoMe never replaces clinical evaluation; PHI must remain private |

| Azu et al., 2012 | General surgery | To discuss impact of Internet use and SoMe and to provide recommendations for professional use | The American Surgeon | Maintaining digital identity is important; physicians need to monitor online presence; profiles should not contain religious or political preferences |

| Lifchez et al., 2012 | Plastic surgery | To review laws governing online communication and to discuss professional behavior online | Journal of Hand Surgery | Do not start doctor-patient relationship online; posts may be disseminated without your knowledge; user has full responsibility for posted content; adhere to HIPAA; OCR can investigate in absence of complaint |

| Vardanian et al., 2012 | Plastic surgery | To evaluate trends of SoMe use among practicing plastic surgeons | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | One third of plastic surgeons limit SoMe use out of concern for patient confidentiality; 25% feel governing bodies should regulate SoMe content |

| Devon, 2013 | General surgery | To discuss ethics of posting mission trip photos on SoMe | JAMA | Establish guidelines before mission trips, obtain consent from international patients |

| Indes et al., 2013 | Vascular surgery | To review applications of SoMe in vascular surgery and limitations of use | Journal of Vascular Surgery | Educate patients that SoMe does not replace phone calls and appointments; avoid inappropriate contact with patients; start with professional website, then provide corresponding link in SoMe profile; start with only one SoMe platform; utilize disclaimers |

| Workman and Gupta, 2013 | Plastic surgery | To evaluate smartphone apps useful to plastic surgeons | Aesthetic Surgery Journal | Advancing technology requires scrutiny of new marketing strategies; follow society codes of ethics |

| Katz, 2014 | Urology | To discuss the EAU guidelines | European Urology | Physicians held to higher standard; guidelines helpful but not as effective as actively teaching trainees online professionalism |

| Loeb et al., 2014 | Urology | To review benefits of SoMe collaboration and journal clubs | European Urology | Remember professional and confidentiality standards; Twitter is open environment seen by anyone; identify yourself as a physician; maintain boundaries |

| Murphy et al., 2014 | Urology | To discuss BJUI SoMe guidelines | British Journal of Urology International | Adherence to proposed guidelines allow for engagement with minimal risk |

| Roupret et al., 2014 | Urology | To discuss benefits and risks of SoME and recommendations of the EAU | European Urology | Protect doctor-patient relationship, consider context, represent yourself only, use caution if mixing personal and professional, assume permanence of posts, maintain limits with patients, refrain from self-promotion |

| Adams et al., 2015 | General surgery | To use a case study to determine ethical issues surrounding use of SoMe in healthcare | Cambridge University Press | Be aware of intent and hierarchy of doctor-patient relationship; stay up-to-date on SoMe platform terms of use |

| Azoury et al., 2015 | General surgery | To review benefits of SoMe, its potential threat to professionalism, and AMA guidelines | Bull Am CollSurg | Be aware of potential dangers; use highest privacy settings; establish professional and personal accounts; maintain boundaries with patients; avoid texting/emailing patients about medical concerns; actively manage one's online presence; avoiding social media out of fear is not the solution |

| Borgmann et al., 2015 | Urology | To determine impact of Twitter on practice, research, and activities | Canadian Urology Association Journal | Follow society (EAU, BJUI) guidelines |

| Ehlert, 2015 | Urology | To review use, risks, and platforms of SoMe | Urology Practice | Online content is permanent, separate accounts does not eliminate risk, audience is infinite, avoid direct contact with patients, utilize disclaimers |

| Fuoco and Leveridge, 2015 | Urology | To understand practices and attitudes of Canadian urologists re: SoMe | British Journal of Urology International | SoMe should be used for collaboration, not patient interactions |

| Herron, 2015 | Orthopedic surgery | To explore opportunities for SoMe use and relevant ethical concerns | Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med | Adhere to HIPAA, follow institutional policies, avoid communicating PHI over SoMe, utilize disclaimers, do not engage patients in social relationships, consent to publish patient information, separate personal and professional accounts |

| Kodadek, 2015 | General surgery | To discuss risks of SoMe and consequences of misuse | Bull Am CollSurg | User has no control over audience, posts are permanent, surgeon use can affect professionalism of entire field |

| Modgil et al., 2015 | Urology | To review the concept of SoMe, opportunities for use in urology, and responsible use | Journal of Clinical Urology | Follow society guidelines; recognize posting as public and permanent; declare COI; avoid direct contact with patients on SoMe |

| Mohuiddin et al., 2015 | General surgery | To measure effectiveness of case-based sessions for training residents in professional use of SoMe | Indian J Surg | Residents interested in changing specific use of SoMe after sessions; sessions made residents more aware of SoMe's impact on career |

| Palacios-Gonzalez, 2015 | Discussed with plastic surgery literature | To determine if consent required for publication of patient images, if SoMe is adequate place for images to be displayed, and if special considerations should be taken into account for SoMe | Med Health Care and Philos | Informed consent mandatory for publishing clinical images, SoMe publication only if consent obtained, consent process must disclose permanence of SoMe posts, providers should moderate comments |

| Langenfeld et al., 2016 | General surgery | To evaluate program directors' approach to teaching online professionalism | Journal of Surgical Education | Online information is permanent; program directors should lead by example. |

| Mata et al., 2016 | Urology | Urology | Develop a digital identity before someone else does; follow society guidelines; maintain professionalism; guard patient confidentiality; posts are permanent. | |

| McLawhorn et al., 2016 | Orthopedic surgery | To review state of SoMe use in orthopedic surgery and unique practice risks | Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med | Keep personal and professional profiles separate; keep medical advice general; always use disclaimers; follow society guidelines; monitor online presence; avoid starting doctor-patient relationship online |

| Rivas et al., 2016 | Urology | To review opportunities and appropriate use of SoMe in urology | Cent European J Urol | Be aware of risks and follow society guidelines |

| Duymus et al., 2017 | Orthopedic surgery | To determine prevalence of SoMe use among orthopedic surgeons and its effects on physician-patient communication | Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma | Be aware that content can be found despite privacy settings; distinct difference between medical and SoMe cultures |

SoMe = social media; EAU = European Association of Urology; OCR = Office of Civil Rights; PHI = protected health information; COI = conflict of interest

Table 2. Summary of Articles Included After Manual Search of Top Three Plastic Surgery Journals.

| Reference | Article Objectives | Journal | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rohrich, 2017 | To discuss impact of SoMe on academic and personal life as well as risks | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Keep professional and personal accounts separate; don't allow patients access to personal profiles; provide a measured responses to inflammatory comments; avoid sensationalism; cite papers to back up posts; consent for any patient video/photo posted |

| Gould et al., 2017 | To provide overview of SoMe and tips for use | Aesthetic Surgery Journal | Impressions made online may be indelible; protect patient privacy; avoid using as sounding board |

| Reissis et al., 2017 | To discuss misuse of SoMe among plastic surgeons and future directions | Aesthetic Surgery Journal | Avoid glamorization of procedures; follow advertising guidelines for SoMe use; need clear society guidelines for SoMe activity |

| Liu, 2017 | To discuss “A Primer on Social Media for Plastic Surgones: What do I need to Know About Social Media and How Can it Help my Practice?” | Aesthetic Surgery Journal | Clarify inaccuracies online; poor judgment reflects on entire profession |

| Nazarian, 2017 | To discuss “Advertising on Social Media: The Plastic Surgeon's Prerogative” | Aesthetic Surgery Journal | Avoiding SoMe makes us obsolete; harness SoMe to educate and provide information on training and board certification |

| Dorfman et al., 2017 | To provide an ethical analysis of patient videos on social media as well as guidelines for appropriate use | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Obtain fully informed consent, recognizing evolving social media platform policies and permanence of online content; promote patient beneficence over surgeon's interests |

| Furnas, 2017 | To discuss “The Ethics of Sharing Plastic Surgery Videos on Social Media: Systematic Literature Review, Ethical Analysis, and Proposed Guidelines” | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Many technological advances met with extreme criticism but later adopted; few unprofessional posts should not ruin potential good of SoMe |

| Lu et al., 2017 | To discuss “The Ethics of Sharing Plastic Surgery Videos on Social Media: Systematic Literature Review, Ethical Analysis, and Proposed Guidelines” | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Raw, graphic videos inappropriate for majority of Snapchat audience; easy to blur professional lines; patient compensation for posts inappropriate |

| Teven et al., 2017 | To review possible negative consequences of posting patient material online and to suggest a specific consent form for social media use | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | Online content is permanent and difficult to remove; loss of copyright once images/videos posted; patients cannot revoke consent once material is posted; should have separate consent form for social media posts |

Of the articles retrieved by the search strategy, ten were related to appropriate social media use in urology, eight in general surgery, six in plastic surgery, three in orthopedic surgery, and one in vascular surgery. An additional article was included due to its extensive discussion regarding the ethics of clinical and surgical photography in social media, and is summarized with the plastic surgery literature. All articles were written between 2010 and 2017.

Urology

The urology literature explored both positive and negative aspects of social media use in surgical practice, more so than other specialties. Recommendations included following society guidelines (if they exist) [1,6], guarding patient confidentiality [6,7], declaring conflicts of interest (COI) [1], avoiding direct contact with patients online [7], considering a potentially infinite audience [7], and remembering that one's online posts are permanent [1,6,7]. Another article recommended creating separate personal and professional accounts and encouraged the use of disclaimers—that the information provided does not substitute for a surgical consultation [7]. Guidelines provided by the American Urological Association (AUA) include 1) be professional, 2) protect confidentiality, 3) allow for interaction, 4) be courteous, 5) exercise discretion, 6) support AUA's identity, and 6) be thoughtful [8]. The European Association of Urology has developed specific guidelines as well, encouraging providers to establish a professional identity in line with career goals, assume that anything posted is permanent, maintain clear limits with patients, refrain from self-promotion, and not accept friend requests from patients [9]. The British Journal of Urology International (BJUI) also suggests users identify themselves as physicians, state that views are not necessarily those of one's institution, alert colleagues if their posts are inappropriate, and strive for accuracy [10]. Finally, Katz suggests that guidelines alone are likely less effective than actively teaching physicians and trainees what constitutes professional online conduct [11].

General and Vascular Surgery

Several articles exist in the general surgery literature. A survey study concluded that program directors should be well versed in the professional use of social media so as to lead residents and colleagues by example [8]. Adams et al. encouraged awareness of intent when posting, as well as staying up-to-date on social media platforms' terms of use and privacy settings. They also suggested that patients may feel pressure to consent to online publication of photographs and videos secondary to the power differential inherent to the physician-patient relationship [12]. Repeated themes included the avoidance of undermining the profession's image, blurring patient/physician boundaries, and HIPAA violations [2]. Using the highest privacy settings, actively managing one's online presence, knowing institutional policies, remembering potential audiences, and being conscious of posts' permanence were emphasized as well [2,13-15]. Azoury et al. reviewed the American Medical Association social media guidelines and purported that avoiding social media entirely was not the solution, especially with current cultural expectations [2]. Consent for both clinical photography, as well as use of photography on social media, was particularly emphasized [16]. The article from the vascular surgery literature warned that patients may rely on social media to communicate with physicians, rather than keeping appointments or returning phone calls. They also suggested starting with one social media platform and expanding according to the needs of one's practice [13].

Orthopedic Surgery

Literature discussing social media use in orthopedic surgery similarly recommended that providers keep personal and professional profiles separate, as well as provide medical advice of a general nature, not substituting for a clinical encounter. Following society guidelines was advised. McLawhorn et al. also warned that physician-patient relationships are easily initiated online if precautions are not taken, and should be actively avoided [17]. Another article reminded readers that all online content is easily found, and social media users should bear this in mind [18]. Further recommendations included following institutional policies, avoiding communication of personal health information (PHI) over social media, using disclaimers, avoiding social relationships with patients, obtaining consent, and separating personal and professional accounts [19].

Plastic Surgery

In the plastic surgery literature, the importance of consent for publication of both identifiable and de-identified material on social media was reiterated. [20,21]. Given the unique risks of social media, a consent form specific to social media posts should be developed [22]. Additionally, the initiation of doctor-patient relationships on social media was discouraged, as well as interactions that could constitute patient care [3,23]. Protecting patient confidentiality, maintaining boundaries, and knowing the potential for limitless dissemination and permanence of content were recurring themes as well [23,24]. Separating professional and personal accounts, avoiding sensationalism, and monitoring one's online presence was advised [21, 25]. Advertising guidelines of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and American Board of Plastic Surgery should be applied to social media use, revisiting these guidelines and amending them with social media in mind as needed [29].

More recently, Dorfman et al. performed an ethical analysis of posting patient videos on social media, emphasizing the importance of fully informed consent, patient beneficence, and balancing competing interests between the patient and surgeon [26]. An invited discussion by Furnas recalled the rapidity of previous cultural changes and the slower nature of ethical responses. Prior technological advances were met with extreme criticism, similar to some responses to social media, yet were eventually adopted. The few plastic surgeons who “cross ethical lines” should not ruin the potential good of social media for the rest of us [27]. Lu et al. acknowledged the importance of addressing challenging ethical questions brought to light by plastic surgery videos on social media, and both discussions mentioned the development of a consent form specific to social media publication by the American Society of Plastic Surgery (ASPS), which is currently underway [28].

Discussion

With the advent of Facebook in 2004, social media rapidly revolutionized culture and social engagement. Social media in surgery has similarly allowed instantaneous online connections with colleagues, facilitating collaboration and propagation of important research findings [13,30]. Surgeons across specialties utilize social media to educate patients about living a healthy lifestyle, screening guidelines, and treatment options [1,19,30]. Social media platforms are used for online journal clubs [31], and channels for advocacy and career development [32]. Vascular surgeons have even touted social media as a way to recruit patients for research studies [13]. Finally, social media is an important marketing and branding agent for plastic surgeons, who provide cosmetic procedures in an increasingly competitive market [3,4]. A large percentage of patients are online, searching for information about surgeons and other patients' experiences. Some surgeons feel (rightly so) that failing to meet them there renders us obsolete [33] and may lead patients down a path toward less qualified “cosmetic surgeons” [43].

However, the use of social media by healthcare providers may invite significant risk if not used with caution. As mentioned previously, HIPAA violations still occur, sometimes by posting seemingly unidentifiable information [10,34]. Additionally, surgeons'posts might be viewed as specific medical advice if appropriate disclaimers are not provided, leading to potentially litigious consequences [7,18]. Surgeons may also begin online communication with patients, inadvertently beginning doctor-patient relationships outside the usual clinical encounter [3,23]. These relationships are easily developed across state lines where physicians are not licensed with real legal implications. Furthermore, surgeons may assume the ear of a specific audience, but social media posts can reach an infinitely large audience with unanticipated views and beliefs [14,35]. A large percentage of this audience is also young and likely immature. Twenty-three percent of SnapChat users are between the ages of 13 and 17 [36], and 59% of Instagram users fall between the ages of 18 and 25 [37]. Even more troubling is that posts are irrevocable, with an infinite potential to offend others if we fail to exercise discernment regarding content [6]. However, some social media content disappears after time, rendering activity difficult to regulate. What is perhaps more problematic are the frequent attempts to provide content that is titillating and sensational.“Medutainment”was initially coined as a term for educating medical students in such a way that information is more readily retained [38,39]. In the context of social media, “medutainment” refers to the use of the surgeon-patient encounter as a source of entertainment for the public under the guise of medical education and degrades the fiduciary responsibility a surgeon has toward his or her patient. For example, a plastic surgeon posting about an intravaginal laser could easily provide information about the procedure and indications for treatment without posting a video of the probe being repeatedly inserted into a patient's vagina. Embracing whatever means necessary to advertise without established standards for policing ourselves results in caveat emptor trumping our fundamental commitment to primum non nocere.

As members of a profession, we submit to a higher standard of behavior, and we have a responsibility both to the profession and to our patients [40]. As the culture evolves, new guidelines become necessary to preserve patients' trust and protect public opinion [35]. The public has already demonstrated poor understanding of plastic surgery [41], and sensationalist social media content will only serve to further confuse. Since other specialties have developed specific guidelines for the use of social media, it may prove beneficial to similarly consider additional recommendations for plastic surgeons engaged with social media.

As we evaluate the current use of social media in plastic surgery and consider the adoption of guidelines, several key principles must be considered. First, consent is necessary but not sufficient. A surgeon who posts a graphic video or photograph of a patient after obtaining consent may not have violated any laws, but this does not qualify the post as professional. One aspect of professionalism is the ability “to communicate and interact in a respectful and productive manner”[42]. As such, our social media activity should similarly be “respectful and productive.”To further develop the definition of professional social media use, the American Medical Association (AMA)published guidelines in 2011. The last recommendation says that “physicians must recognize that actions online and content posted may negatively affect their reputations among patients and colleagues, may have consequences for their medical careers, and can undermine public trust in the medical profession” [35]. Furthermore, the Federation of State Medical Boards maintains the “authority to discipline physicians for unprofessional behavior relating to the inappropriate use of social networking media,” which includes inappropriate communication with patients, derogatory remarks about patients, or “use of the Internet for unprofessional behavior” [43]. Unfortunately, certain social media accounts have made it clear that a few plastic surgeons struggle to discern what constitutes respective, productive, and professional content.

As part of our professional duty, we must also recognize the physician-patient power differential. The father of peer review, Henry Beecher, noted that patients consent to almost anything a physician proposes simply out of trust [44]. We must guard against this by facilitating fully informed consent, disclosing that online content is irrevocable and can reach unanticipated audiences. Consent should be obtained for de-identified material as well, since the patient has trusted the surgeon to keep all information surrounding their care private. Furthermore, providing incentives to patients for allowing online publication of photographs and videos should be prohibited, which is in line with the Code of Ethics prohibition of promotions wherein the prize is a surgical procedure.

Notwithstanding the valuable recommendations offered by various surgical specialties, the literature was unable to clarify what defines a post as unprofessional. This may seem like common sense— as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said, “I know it when I see it”—but various social media posts would suggest it is not. The standards for photography and advertising set forth by our societies should also govern social media activity. Applying these standards to social media content may also serve to distinguish board-certified plastic surgeons from other cosmetic “surgeons” on social media [45]. Furthermore, an emphasis on board certification and its importance could successfully replace sensational social media content while still maintaining a competitive edge. Context must be considered as well, as photographs of breasts or genitalia in a journal are not equivalent to mass viewing on social media. Prudence suggests erring toward a more conservative definition of professionalism on social media given the potentially infinite and impressionable audience. Moving forward, our specialty would benefit from evolving guidelines set forth by our societies, as well as a specific consent form for the publication of material on social media, which is currently being overseen by the ASPS social media task force. Historically when professionals have failed to self-regulate, it often falls to the attorneys, lawmakers, and governing bodies to intervene on behalf of the public. As a specialty we would do well to address these issues before outside forces intercede. However, the authors applaud the work that the ASPS has done thus far to curb the small group of plastic surgeons who are using social media unprofessionally, as well as its commitment to disciplinary action in the Code of Ethics in response to unprofessional conduct.

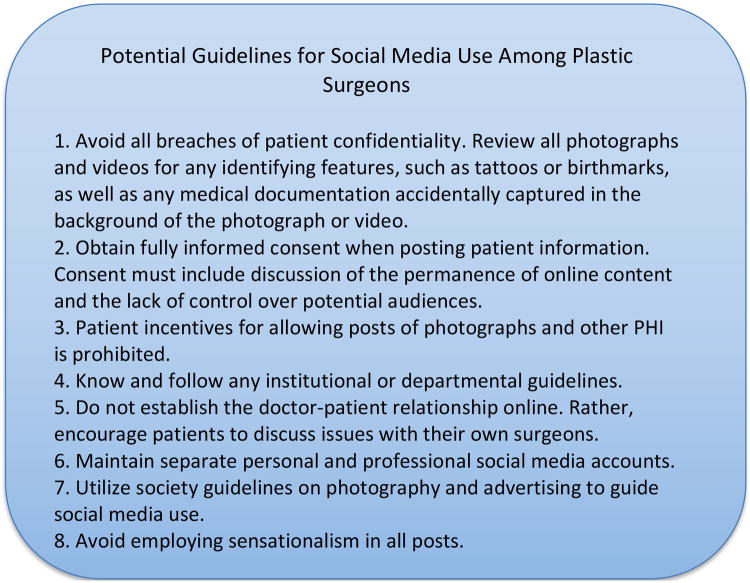

It is imperative to adapt as the culture evolves in order to remain relevant to our patients and provide accurate information about plastic surgery procedures. Creating an online culture of transparency in surgery is possible while still maintaining professionalism, but we must provide clearer direction on how to accomplish this (Figure 2). While maintaining relevance through professional social media activity, we must also protect patients from inaccurate information and false advertising. Board-certified plastic surgeons are woefully under-represented in plastic surgery-related content on social media, which renders it difficult for patients to find credible resources and qualified surgeons and renders our online presence all the more critical [46]. If we do not engage with patients online, the only available information will be from non-core practitioners. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is not to discourage participation in social media but rather to subscribe to a higher standard of online professionalism.

Figure 2.

Potential guidelines for social media use among plastic surgeons.

While our study's strengths lie in its comprehensive search of the surgical literature, it is not without limitations. Given that ethical codes and guidelines are often found in society newsletters or other non-peer reviewed publications, it is possible that more specific recommendations regarding professional social media use were missed. However, given the extensive body of literature on the use of social media and its recent uptake by surgeons, it is more likely that specific guidelines have yet to be developed.

Conclusions

Social media use is indispensable for many plastic surgeons [47]. The various social media platforms offer tremendous opportunities for educating patients, collaborating with colleagues, advertising, and disseminating research findings. However, merely avoiding HIPAA violations is an infinitesimally small part of maintaining online professionalism. The recommendations provided must function as the beginning of a vitally important discussion, and one that must continue to evolve as technology and social media platforms change. It is critical for leaders in plastic surgery to proactively work toward a more concrete definition of online professionalism in order to maintain our reputation and effectiveness long-term.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure Statement: Katelyn G. Bennett is currently supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: 1F32DE027604-01

We have no commercial associations to disclose. Katelyn G. Bennett is supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: 1F32DE027604-01.

Footnotes

This paper has not been presented at any meetings.

References

- 1.Modgil V, Cashman S, Bedi N, et al. Social media in urology—what is all the fuss about? J of Clin Urology Vol. 2015;8(3):160–165. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoury SC, Bliss LA, Ward WH, et al. Surgeons and social media: threat to professionalism or an essential part of contemporary surgical practice? Bull Am Coll Surg. 2015 Aug;100(8):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong WW, Gupta SC. Plastic surgery marketing in a generation of “tweeting”. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(8):972–6. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11423764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardanian AJ, et al. Social media use and impact on plastic surgery practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(5):1184–93. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318287a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy DG, et al. Engaging responsibly with social media: the BJUI guidelines. BJU Int. 2014;114(1):9–11. doi: 10.1111/bju.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mata DA, et al. Curating a Digital Identity: What Urologists Need to Know About Social Media. Urology. 2016;97:5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehlert MJ. Social media and online communication: clinical urology practice in the 21st century. UrolPract. 2014;2(1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Social media best practices. [Accessed September 30, 2017]; Available at: http://auanet.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=20294.

- 9.Roupret M, et al. European Association of Urology (@ Uroweb) Recommendations on the Appropriate Use of Social Media. European Urology. 2014;66(4):628–632. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy DG, et al. Engaging responsibly with social media: The British Journal of Urology International (BJUI) guidelines. Bju International. 2014;114(1):9–11. doi: 10.1111/bju.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz MS. Social Media and Medical Professionalism: The Need for Guidance. European Urology. 2014;66(4):633–634. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams SA, van Veghel D, Dekker L. Developing a Research Agenda on Ethical Issues Related to Using Social Media in Healthcare Lessons from the First Dutch Twitter Heart Operation. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2015;24(3):293–302. doi: 10.1017/S0963180114000619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Indes JE, et al. Social media in vascular surgery. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2013;57(4):1159–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landman MP, et al. Guidelines for Maintaining a Professional Compass in the Era of Social Networking. Journal of Surgical Education. 2010;67(6):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodadek LM. First-place essay-con: the writing is on the (Facebook) wall: the threat posed by social media. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2015 Nov;100(11):21–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devon KM. Status Update: Whose Photo Is That? 18. Vol. 309. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association; 2013. pp. 1901–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLawhorn AS, et al. Social media and your practice: navigating the surgeon-patient relationship. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9(4):487–495. doi: 10.1007/s12178-016-9376-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duymus TM, et al. Social media and Internet usage of orthopaedic surgeons. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2017;8(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herron PD. Opportunities and ethical challenges for the practice of medicine in the digital era. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(2):113–7. doi: 10.1007/s12178-015-9264-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palacios-Gonzalez C. The ethics of clinical photography and social media. Medicine Health Care and Philosophy. 2015;18(1):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s11019-014-9580-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohrich RJ. So, Do You Want to Be Facebook Friends? How Social Media Have Changed Plastic Surgery and Medicine Forever. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2017;139(4):1021–1026. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teven CM, Park JE, Song DH. Social Media and Consent: Are Patients Adequately Informed? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lifchez SD, et al. Guidelines for Ethical and Professional Use of Social Media in a Hand Surgery Practice. Journal of Hand Surgery-American Volume. 2012;37A(12):2636–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould DJ, Grant Stevens W, Nazarian S. A Primer on Social Media for Plastic Surgeons: What Do I Need to Know About Social Media and How Can It Help My Practice? Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(5):614–619. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEvenue G, et al. How Social Are We? A Cross-Sectional Study of the Website Presence and Social Media Activity of Canadian Plastic Surgeons. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2016;36(9):1079–1084. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorfman RG, et al. The Ethics of Sharing Plastic Surgery Videos on Social Media: Systematic Literature Review, Ethical Analysis, and Proposed Guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):825–836. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furnas HJ. Discussion: The Ethics of Sharing Plastic Surgery Videos on Social Media: Systematic Literature Review, Ethical Analysis, and Proposed Guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):837–839. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu J, Nigam M, Song DH. Discussion: The Ethics of Sharing Plastic Surgery Videos on Social Media: Systematic Literature Review, Ethical Analysis, and Proposed Guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):840–841. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reissis D, Shiatis A, Nikkhah D. Advertising on Social Media: The Plastic Surgeon's Prerogative. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(1):NP1–NP2. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivas JG, Socarras MR, Blanco LT. Social Media in Urology: opportunities, applications, appropriate use and new horizons. Central European Journal of Urology. 2016;69(3):293–298. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2016.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loeb S, Catto J, Kutikov A. Social Media Offers Unprecedented Opportunities for Vibrant Exchange of Professional Ideas Across Continents. European Urology. 2014;66(1):118–119. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgmann H, et al. Novel survey disseminated through Twitter supports its utility for networking, disseminating research, advocacy, clinical practice and other professional goals. Cuaj-Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2015;9(9-10):E713–E716. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nazarian S. Comments on “Advertising on Social Media: The Plastic Surgeon's Prerogative”. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2017;37(2):20–21. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagu T, et al. Content of weblogs written by health professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1642–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0726-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shore R, et al. Report of the AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: professionalism in the use of social media. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22(2):165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snapchat user demographics: Distribution of Snapchat users in the United States as of February 2016, by age. [Accessed October 1, 2017]; Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/326452/snapchat-age-group-usa/

- 37.The Instagram demographics and usage statistics marketers need to know in 2017. [Accessed October 1, 2017]; Available at: http://mediakix.com/2016/09/13-impressive-instagram-demographics-user-statistics-to-see/#gs.AqXjLNU.

- 38.Medutainment and Emergency Medicine. Part 2. Why are we talking about it? [Accessed January 11, 2018]; Available at: http://stemlynsblog.org/medutainment-and-emergency-medicine-part-2-why-are-we-talking-about-it/

- 39.Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013 Jun;88(6):893–901. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vercler CJ. Narrating Bioeth. 1. Vol. 5. Spring; 2015. Surgical ethics: surgical virtue and more; pp. 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Blacam C, et al. Public perception of Plastic Surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hochberg MS, Berman RS, Pachter HL. Professionalism in Surgery: Crucial Skills for Attendings and Residents. Adv Surg. 2017;51(1):229–249. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Model Guidelines for the Appropriate Use of Social Media and Social Networking in Medical Practice. Report of the Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism Adopted as policy by the House of Delegates of the Federation of State Medical Boards. [Accessed January 29, 2018]; Available at: https://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/pub-social-media-guidelines.pdf.

- 44.Beecher HK. Ethics and clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1966;274(24):1354–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196606162742405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cosmetic surgery advertising on Instagram misleading. [Accessed October 1, 2017]; Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/885055?nlid=117667_2983&src=WNL_mdplsfeat_170905_mscpedit_plas&uac=111321SV&spon=48&impID=1425970&faf=1.

- 46.Dorfman RG, Vaca EE, Mahmood E, et al. Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing. Aesthet Surg J. 2017 Aug 30; doi: 10.1093/asj/sjx120. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel A, et al. “Friending” Facebook? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):45e–6e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]