Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The objective of this study was to characterize risk for and temporal trends in postpartum hemorrhage across hospitals with different delivery volumes.

STUDY DESIGN:

This study used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample to characterize risk for postpartum hemorrhage from 1998 to 2011. Hospitals were classified as having either low, moderate or high delivery volume (≤1000, 1001 to 2000, >2000 deliveries per year respectively). The primary outcomes included postpartum hemorrhage, transfusion, and related severe maternal morbidity. Adjusted models were created to assess factors associated with hemorrhage and transfusion.

RESULTS:

Of 55,140,088 deliveries included for analysis 1,512,212 (2.7%) had a diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage and 361,081 (0.7%) received transfusion. Risk for morbidity and transfusion increased over the study period, while the rate of hemorrhage was stable ranging from 2.5% to 2.9%. After adjustment, hospital volume was not a major risk factor for transfusion or hemorrhage.

DISCUSSION:

While obstetric volume does not appear to be a major risk factor for either transfusion or hemorrhage, given that transfusion and hemorrhage-related maternal morbidity are increasing across hospital volume categories, there is an urgent need to improve obstetrical care for postpartum hemorrhage. That risk factors are able to discriminate women at increased risk supports routine use of hemorrhage risk assessment.

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States1 and risk for severe hemorrhage appears to be rising.2–5 Maternal mortality reviews have demonstrated that maternal deaths caused by hemorrhage are the most likely to be preventable.6,7 Major safety and quality improvement initiatives, such as the Hemorrhage Bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety, have been developed to reduce maternal risk by improving preparedness for, recognition of, and responses to maternal hemorrhage.5,8

Understanding how hospital delivery volume relates to risk for postpartum hemorrhage may be important in improving patient care and reducing risk. If hemorrhage-related morbidity were found to be increasing across hospital volume settings, this would support the need for quality improvement initiatives focused on this issue at all hospitals; in fact, prior research has demonstrated possible increased risk at low-volume centers.3 Efforts to improve safety culture in diagnosing and responding to hemorrhage could lead to meaningfully improved outcomes. Secondly, understanding maternal risk would add to knowledge on obstetric quality: Little is known regarding how procedural volume (number of deliveries) relates to the complication rate (postpartum hemorrhage) in this context.

Given that (i) the epidemiology of postpartum hemorrhage may vary based on hospital volume, and (ii) it is unclear to what degree risk varies across hospitals with different delivery volumes, the purpose of this analysis was to determine whether risk was increasing temporally across obstetric volume settings for postpartum hemorrhage, hemorrhage-related severe morbidity, and transfusion.

METHODS

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were used for the analysis. The NIS is the largest publicly available, allpayer inpatient database in the United States and it contains a sample of approximately 20% of all hospitals within the United States selected to generate a sample that is maximally representative of all U.S. hospitals. All discharge claims in selected hospitals are included through 2011. Hospitals included for sampling in the NIS encompass academic, community, nonfederal, general, and specialty-specific centers throughout the United States. Approximately 8 million hospital stays from 45 states in 2010 are included in the NIS.9 Sampling weights are included in the NIS and can be applied to provide national estimates and were used in this analysis. Due to the de-identified nature of the data set, institutional review board exemption was obtained from Columbia University to perform this study.

We analyzed women from 16 to 49 years of age hospitalized for a delivery between 1998 and 2011. Patients were included if International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, (ICD-9) billing codes v27.x and 650 were present; these codes identify nearly all delivery hospitalizations.10 Patients at very high risk for peripartum hysterectomy with the following diagnoses were excluded; cervical cancer (180.x), ovarian cancer (183.x), vasa previa (663.5x), placenta acceta (667.0x, 667.1x), and placenta previa (641.0x, 641.1x) in the setting of prior cesarean delivery (654.x). The primary outcomes used in the analysis were: (i) postpartum hemorrhage (666.x), (ii) transfusion (99.x) and (iii) severe maternal morbidity related to postpartum hemorrhage (666.x) and/or transfusion (99.x). The hypothesis of this study was that risk was increasing temporally across hospitals with low, medium, and high clinical volume. Given that the diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage is based on a clinical assessment of blood loss that may be inaccurate and varies for vaginal and cesarean delivery,10 evaluating other events such as transfusion or severe morbidity associated with hemorrhage may add a more specific assessment of maternal risk. To classify severe morbidity, measures and diagnoses of severe morbidity were reviewed in the research literature.1,11–13 This analysis utilized fourteen diagnoses of acute organ injury and critical illness used as outcomes for a validated obstetric comorbidity index: acute heart failure, acute liver disease, acute myocardial infarction, acute renal failure, acute respiratory failure, coagulopathy/ disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), coma, delirium, puerperal cerebrovascular disorders, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, shock, status asthmaticus, and status epilepticus.12

For each hospital, we calculated the total number of delivery hospitalizations and divided this by the number of years in which a hospital had at least one delivery. Hospitals were categorized as low (≤1000 deliveries per year), medium (1001 to 2000 deliveries per year), or high volume (>2000 deliveries per year). Prior analyses have used varying obstetric volume cutoffs;14,15 the volume categories used in this analysis were chosen because they represent easily interpretable and clinically meaningful distinctions in obstetric volume. Based on prior analyses, approximately 25% of deliveries occur annually in low-volume hospitals, 25% in medium volume hospitals, and 50% in high volume hospitals. In addition to annualized delivery volume, hospital characteristics included location (urban versus rural), teaching status (teaching versus nonteaching), hospital bed size, and region (Eastern, Midwest, South, or West).

Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage were determined by a review of the literature and included in the model. These included mode of delivery (vaginal operative or nonoperative delivery, primary or repeat cesarean delivery), induction of labor, multiple gestation, placental abruption, uterine fibroids, stillbirth, antepartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, polyhydramnios, placenta previa, suspected macrosomia, preexisting diabetes, asthma, chronic hypertension and preeclampsia/eclampsia.2,11,16–18 Patient demographic characteristics were also individually evaluated and included for analysis. Patient characteristics included maternal age, race (white, black, Hispanic ethnicity), insurance status, year of discharge, and median household income determined the patient’s residential ZIP code.

Rates of postpartum hemorrhage, transfusion, and severe morbidity were calculated and are demonstrated as temporal trends. Adjusted risk ratios for these outcomes accounting for demographic, hospital, and medical/obstetric risk factors were derived from fitting weighted random-intercept log-linear regression models based on the Poisson distribution. Hospitals formed the random intercept term. To obtain population prevalences all analyses were weighted by the sampling weights in the NIS data. To determine how well the randomintercept models accounted for patient risk for the three primary outcomes, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were created and the area under the curve (AUC) was determined. Sensitivity analyses for the ROC curves based on fixed effects log-linear Poisson models were performed to test the discriminatory ability of models based on measurable demographic, obstetric, and hospital factors apart from center clustering effects. The random-intercept models were then repeated for each of the three outcomes (hemorrhage, transfusion, and morbidity) based on the hospital delivery volume categories (low, moderate, and high volume).

Finally, it is well established that risk for severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations in the US is increasing.1 To better differentiate morbidity risk associated specifically with hemorrhage from increased comorbid risk in the general population, we (i) characterized severe morbidity related to hemorrhage/transfusion as a proportion of severe morbidity occurring for all delivery hospitalizations, and (ii) evaluated risks of severe morbidity in women with and without transfusion/hemorrhage over the study period. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC.).

RESULTS

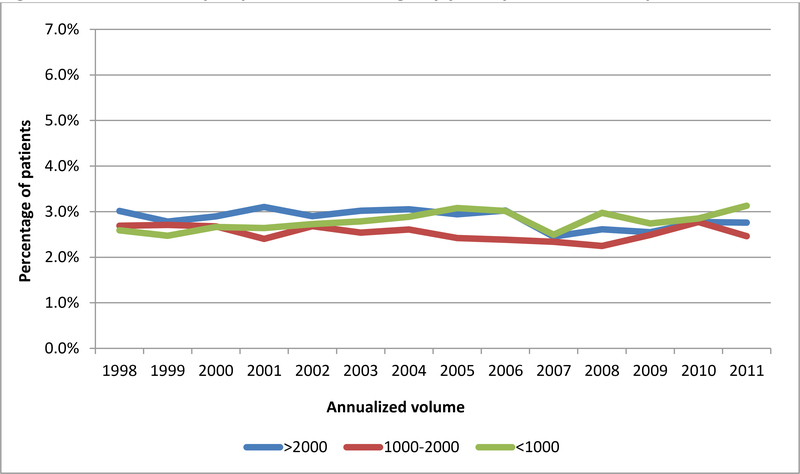

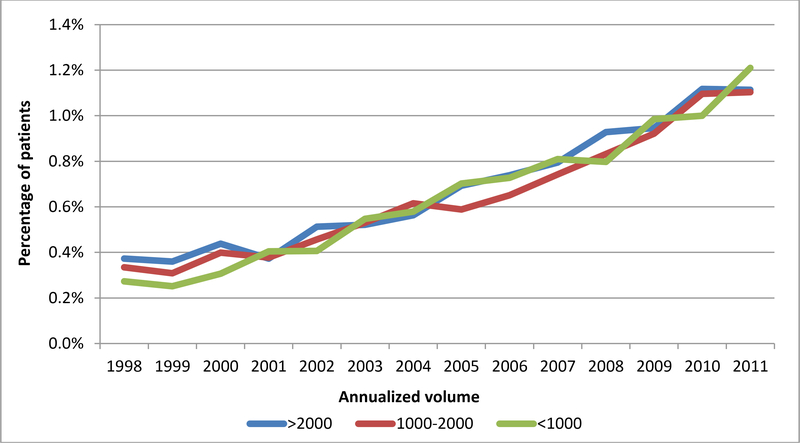

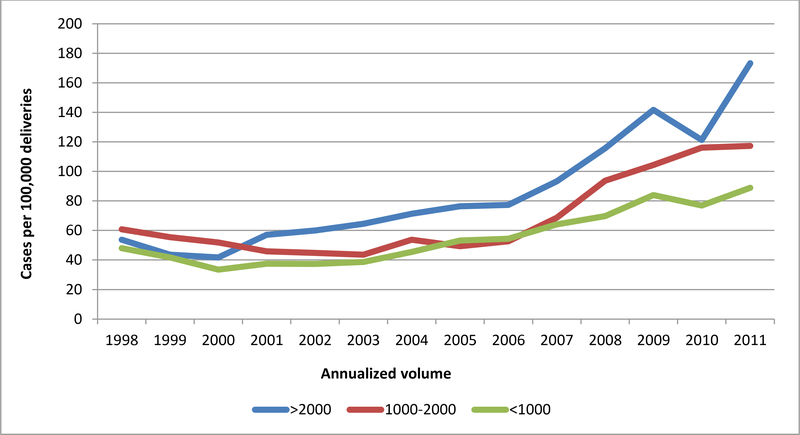

55,140,088 deliveries were included in the analysis. Postpartum hemorrhage occurred at a rate of 2.7% (n=1,512,212) overall, and at rates of 2.9%, 2.5%, and 2.8% at low, medium and high volume hospitals, respectively. Blood transfusion occurred overall at a rate of 0.7% (n=361,081), and at rates of 0.7%, 0.6%, and 0.7% at low, medium, and high volume hospitals, respectively. Severe maternal morbidity associated with postpartum hemorrhage and/or blood transfusion occurred in 75.3 per 100,000 deliveries, and rates of 54.8, 68.4, and 86.0 at low, medium and high volume hospitals, respectively. The most common causes of hemorrhage/transfusion-related morbidity included coagulopathy/DIC (present in 37.8% of morbidity cases), respiratory failure (17.7%), shock (15.8%), acute renal failure (14.9%), acute heart failure (9.7%), and pulmonary edema (8.1%). While the risks of postpartum hemorrhage were stable throughout the study period (Figure 1A), the risks of transfusion increased over time, but were similarly across volume categories (Figure 1B). In terms of hemorrhage/transfusion related morbidity, the risk increased for all hospital volume categories, but the increase was largest at high volume centers (Figure 1C). Risk factors associated with the highest rates of severe maternal morbidity included stillbirth (1148.2 per 100,000), antepartum hemorrhage (1444.8 per 100,000), and abruption (991.1 per 100,000) (Table 1).

Figure 1A. Incidence of postpartum hemorrhage by year by annualized hospital volume.

Legend. Figure 1A demonstrates rates of postpartum hemorrhage by hospital volume category in low volume (<1000 deliveries per year), moderate volume (1000–2000 deliveries per year), and high volume hospitals (>2000 deliveries per year).

Figure 1B. Incidence of transfusion by year by annualized hospital volume.

Legend. Figure 1B demonstrates rates of transfusion by hospital volume category.

Figure 1C. Incidence of severe maternal morbidity associated with transfusion and/or hemorrhage by annualized hospital volume.

Legend. Figure 1C demonstrates rates of severe maternal morbidity associated with transfusion and/or hemorrhage per 100,000 delivery hospitalizations.

Table 1.

Demographic, obstetrical, medical characteristics

| All patients n, (%) | Postpartum hemorrhage, n (%) | Transfusion, n (%) | Severe morbidity rate* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All deliveries | 55,140,088 | 1,512,212 (2.7) | 361,081 (0.7) | 75.3 |

| Annualized delivery | ||||

| <1000 | 11,230,325 | 320,153 (2.9) | 74,962 (0.7) | 54.8 |

| 1000–2000 | 13,616,378 | 343,646 (2.5) | 87,362 (0.6) | 68.4 |

| >2000 | 30,367,385 | 848,414 (2.8) | 198,757 (0.7) | 86.0 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Primary cesarean | 9,239,847 (16.8) | 204,178 (2.2) | 146,377 (1.6) | 209.3 |

| Repeat cesarean | 6,700,795 (12.2) | 89,215 (1.3) | 67,861 (1.1) | 98.9 |

| Operative vaginal | 3,778,877 (6.9) | 143,935 (3.8) | 23,948 (0.6) | 62.1 |

| Non-operative vaginal | 35,494,568 | 1,074,884 (3.0) | 122,895(0.4) | 37.3 |

| Labor induction | 9,850,056 (17.9) | 354,209 (3.6) | 58,401 (0.6) | 74.9 |

| Multiple gestation | 950,569 (1.7) | 51,974 (5.5) | 26,957 (2.8) | 347.3 |

| Stillbirth | 368,156 (0.7) | 22,857 (6.2) | 14,320 (3.9) | 1148.2 |

| Placental abruption | 573,709 (1.0) | 27,182 (4.7) | 31,589 (5.5) | 991.1 |

| Fibroids | 398,697 (0.7) | 13,423 (3.4) | 7,415 (1.9) | 236.8 |

| Antepartum | 140,432 (0.3) | 6,435 (4.6) | 7,612 (5.4) | 1444.8 |

| Polyhydramnios | 350,453 (0.6) | 11,318 (3.2) | 4,017 (1.2) | 145.1 |

| Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | 2,054,401 (3.7) | 121,060 (5.9) | 57,554 (2.8) | 569.9 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 952,954 (1.7) | 61,228 (6.4) | 13,683 (1.4) | 267.4 |

| Placenta previa | 217,265 (0.4) | 13,329 (6.1) | 16,766 (7.7) | 540.4 |

| Suspected macrosomia | 1,418,938 (2.6) | 51,895 (3.7) | 10,108 (0.7) | 75.7 |

| Asthma | 1,204,754 (2.2) | 37,690 (3.1) | 11,852 (1.0) | 135.6 |

| Chronic hypertension | 806,335 (1.5) | 27,684 (3.4) | 12,394 (1.5) | 351.8 |

| Preexisting diabetes | 423,618 (0.8) | 10,725 (2.5) | 5,117 (1.2) | 200.3 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 16–17 | 1,693,316 (3.1) | 52551 (3.1) | 14,137 (0.8) | 53.6 |

| 18–19 | 3,889,546 (7.1) | 116070 (3.0) | 31,270 (0.8) | 58.0 |

| 20–24 | 13,592,857 | 381937 (2.8) | 94,603 (0.7) | 60.4 |

| 25–29 | 15,189,026 | 411644 (2.7) | 86,492 (0.6) | 66.0 |

| 30–34 | 13,036,596 | 342022 (2.6) | 75,492 (0.6) | 81.3 |

| 35 | 7,812,747 (14.2) | 207987 (2.7) | 59,086 (0.8) | 122.4 |

| Discharge year | ||||

| 1998 | 3,505,578 (6.4) | 95,419 (2.7) | 10,981 (0.3) | 54.1 |

| 1999 | 3,656,664 (6.6) | 95,117 (2.6) | 10,603 (0.3) | 46.2 |

| 2000 | 3,884,785 (7.0) | 105,525 (2.7) | 13,863 (0.4) | 42.5 |

| 2001 | 3,815,910 (6.9) | 102,237 (2.7) | 14,896 (0.4) | 49.8 |

| 2002 | 3,988,487 (7.2) | 109,814 (2.8) | 17,535 (0.4) | 51.8 |

| 2003 | 3,927,782 (7.1) | 109,241 (2.8) | 21,129 (0.5) | 54.5 |

| 2004 | 4,070,598 (7.4) | 116,154 (2.9) | 23,784 (0.6) | 62.2 |

| 2005 | 4,096,636 (7.4) | 118,215 (2.9) | 27,506 (0.7) | 64.9 |

| 2006 | 4,140,424 (7.5) | 118,060 (2.9) | 29,371 (0.7) | 66.5 |

| 2007 | 4,418,172 (8.0) | 108,317 (2.5) | 34,969 (0.8) | 82.3 |

| 2008 | 4,126,560 (7.5) | 112,245 (2.7) | 34,297 (0.8) | 101.3 |

| 2009 | 4,044,383 (7.3) | 106,901 (2.6) | 38,911 (1.0) | 120.8 |

| 2010 | 3,786,793 (6.9) | 106,678 (2.8) | 39,589 (1.1) | 111.8 |

| 2011 | 3,751,315 (6.8) | 108,289 (2.9) | 43,648 (1.2) | 142.4 |

| Household income | ||||

| Lowest quartile | 10,849,242 | 286,576 (2.6) | 105,884 (1.0) | 93.6 |

| Second quartile | 13,432,526 | 375,337 (2.8) | 92,782 (0.7) | 73.7 |

| Third quartile | 13,873,587 | 392,816 (2.8) | 78,482 (0.6) | 70.1 |

| Highest quartile | 16,066,371 | 428,024 (2.7) | 74,309 (0.5) | 67.3 |

| Unknown | 992,362 (1.8) | 29,459 (3.0) | 9,624 (1.0) | 96.0 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Medicare | 268,832 (0.5) | 6,951 (2.6) | 3,604 (1.3) | 84.1 |

| Medicaid | 21,779,883 | 608,944 (2.8) | 182,847 (0.8) | 68.3 |

| Private | 29,663,328 | 793,391 (2.7) | 146,340 (0.5) | 83.8 |

| Self pay | 1,875,371 (3.4) | 56,339 (3.0) | 17,553 (0.9) | 65.3 |

| Other | 1,504,701 (2.7) | 43,501 (2.9) | 9,957 (0.7) | 61.1 |

| Unknown | 121,973 (0.2) | 3,086 (2.5) | 779 (0.6) | 84.1 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 22,688,983 | 588,946 (2.6) | 115,675 (0.5) | 62.5 |

| Black | 5,672,291(10.3) | 146,131 (2.6) | 65,751 (1.2) | 136.2 |

| Hispanic | 9,741,873 (17.7) | 275,760 (2.8) | 82,293 (0.8) | 80.8 |

| Other | 4,326,772 (7.8) | 130,228 (3.0) | 32,724 (0.8) | 113.2 |

| Unknown | 1,278,4169 | 371,148 (2.9) | 64,637 (0.5) | 53.9 |

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| Small | 6,279,303 (11.4) | 176,830 (2.8) | 39,045 (0.6) | 61.5 |

| Medium | 14,926,928 | 404,355 (2.7) | 99,860 (0.7) | 69.7 |

| Large | 33,844,469 (27.1) | 927,213 (2.7) | 221,508 (0.7) | 80.3 |

| Unknown | 163,388 (0.3) | 3,814 (2.3) | 669 (0.4) | 70.6 |

| Hospital Location | ||||

| Rural | 7,237,065 (13.1) | 224,167 (3.1) | 50,914 (0.7) | 53.8 |

| Urban | 47,813,635 | 1,284,231 (2.7) | 309,498 (0.7) | 78.5 |

| Unknown | 163,388 (0.3) | 3,814 (2.3) | 669 (0.4) | 70.6 |

| Hospital Region | ||||

| Northeast | 921,6070 (16.7) | 237,915 (2.6) | 65,159 (0.7) | 77.0 |

| Midwest | 11,912,631 | 358,669 (3.0) | 64,405 (0.5) | 62.8 |

| South | 20,465,815 | 492,342 (2.4) | 154,177 (0.8) | 77.2 |

| West | 13,619,571 | 423,285 (3.1) | 77,340 (0.6) | 82.2 |

| Hospital Teaching | ||||

| Non-teaching | 29,899,880 | 735,980 (2.5) | 176,936 (0.6) | 60.1 |

| Teaching | 25,150,820 | 772,419 (3.1) | 183,476 (0.7) | 93.3 |

| nknown | 163,388 (0.3) | 3,814 (2.3) | 669 (0.4) | 70.6 |

cases of severe morbidity per 100,000 deliveries associated with postpartum hemorrhage and/or transfusion

In the adjusted analysis, hospital volume was not associated with risk for hemorrhage, transfusion, or severe morbidity (Table 2) with the exception of a small increase in risk for hemorrhage in low volume hospitals (adjusted risk ratio (RR) 1.14 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04–1.25). While primary and repeat cesarean were associated with lower risk of postpartum hemorrhage compared to non-operative vaginal delivery, risk was higher with primary and repeat cesarean for both transfusion and severe morbidity. While conditions such as stillbirth, placental abruption, and antepartum hemorrhage were associated with modestly increased probability of hemorrhage (RR 1.66 95% CI 1.59–1.73, RR 1.67 95% CI 1.61–1.74, RR 1.51 95% CI 1.40–1.64, respectively), they were associated with very large increases in risk for transfusion (RR 3.25 95% CI 3.13–3.39, RR 4.18 95% CI 4.05–4.30, RR 4.10 95% CI 3.88–4.33, respectively) and severe morbidity (RR 7.97 95% CI 7.31–8.67, RR 4.88 95% CI 4.51–5.26, RR 6.68 95% CI 5.91–7.55, respectively). While year of delivery was not a major determinant of hemorrhage with risk ratios over the study period ranging from 0.95 to 1.09, the latter years of the study period were associated with increased risk for transfusion and severe morbidity; with 1998 as a reference the risk ratios for transfusion and severe morbidity in 2011 were 2.82 (95% CI 2.54–3.12) and 2.04 (95% CI 1.76–2.35) respectively. Severe maternal morbidity associated with postpartum hemorrhage or transfusion increased with increasing maternal age but similar trends were not seen for postpartum hemorrhage or blood transfusion. Insurance status, household income, hospital location, region and bed size did not affect any of the three outcomes.

Table 2.

Log linear regression models for postpartum hemorrhage, hemorrhage associated with blood transfusion and maternal morbidity associated with postpartum hemrorhage and/or blood transfusion.

| Postpartum hemorrhage | Hemorrhage with transfusion | Severe maternal morbidity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annualized delivery | ||||||

| <1000 | 1.14 | (1.04–1.25) | 1.10 | (0.99–1.23) | 1.02 | (0.91–1.15) |

| 1000–2000 | 1.04 | (0.97–1.13) | 1.04 | (0.94–1.14) | 0.99 | (0.90–1.09) |

| >2000 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Primary cesarean | 0.59 | (0.56–0.62 | 2.78 | (2.72–2.85) | 3.35 | (3.15–3.55) |

| Repeat cesarean | 0.47 | (0.44–0.49) | 2.45 | (2.39–2.52) | 2.22 | (2.07–2.38) |

| Operative vaginal | 1.26 | (1.23–1.30) | 1.95 | (1.90–2.01) | 1.88 | (1.71–2.07) |

| Non-operative vaginal | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Labor induction | 1.24 | (1.22–1.26) | 1.02 | (1.00–1.04) | 0.98 | (0.92–1.05) |

| Multiple gestation | 2.32 | (2.25–2.39) | 2.37 | (2.29–2.45) | 1.80 | (1.64–1.98) |

| Stillbirth | 1.66 | (1.59–1.73) | 3.25 | (3.13–3.39) | 7.97 | (7.31–8.67) |

| Placental abruption | 1.67 | (1.61–1.74) | 4.18 | (4.05–4.30) | 4.88 | (4.51–5.26) |

| Fibroids | 1.46 | (1.39–1.53) | 1.39 | (1.33–1.47) | 1.13 | (0.98–1.30) |

| Antepartum | 1.51 | (1.40–1.64) | 4.10 | (3.88–4.33) | 6.68 | (5.91–7.55) |

| Polyhydramnios | 1.15 | (1.10–1.21) | 1.19 | (1.11–1.26) | 1.21 | (0.98–1.49) |

| Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | 2.23 | (2.17–2.29) | 2.80 | (2.72–2.88) | 5.48 | (5.13–5.84) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 2.17 | (2.09–2.25) | 1.77 | (1.67–1.87) | 2.20 | (1.98–2.44) |

| Placenta previa | 2.88 | (2.74–3.02) | 5.12 | (4.89–5.36) | 3.15 | (2.76–3.59) |

| Suspected macrosomia | 1.57 | (1.53–1.61) | 1.05 | (1.01–1.10) | 0.72 | (0.62–0.85) |

| Asthma | 1.02 | (0.99–1.05) | 1.10 | (1.06–1.15) | 1.28 | (1.15–1.42) |

| Chronic hypertension | 1.04 | (1.01–1.08) | 1.01 | (0.97–1.05) | 1.32 | (1.21–1.44) |

| Preexisting diabetes | 0.86 | (0.82–0.90) | 0.96 | (0.90–1.02) | 1.01 | (0.86–1.18) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 16–17 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| 18–19 | 0.98 | (0.95–1.00) | 0.96 | (0.92–1.00) | 1.08 | (0.92–1.28) |

| 20–24 | 0.95 | (0.93–0.97) | 0.87 | (0.83–0.90) | 1.19 | (1.03–1.38) |

| 25–29 | 0.93 | (0.91–0.95) | 0.78 | (0.75–0.81) | 1.38 | (1.19–1.61) |

| 30–34 | 0.92 | (0.90–0.94) | 0.80 | (0.76–0.83) | 1.66 | (1.42–1.93) |

| ≥35 | 0.95 | (0.92–0.97) | 0.90 | (0.86–0.94) | 2.09 | (1.79–2.43) |

| Discharge year | ||||||

| 1998 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| 1999 | 0.98 | (0.93–1.03) | 1.00 | (0.91–1.09) | 0.87 | (0.75–1.02) |

| 2000 | 0.99 | (0.94–1.05) | 1.11 | (1.01–1.22) | 0.81 | (0.69–0.96) |

| 2001 | 1.01 | (0.96–1.07) | 1.17 | (1.06–1.29) | 0.92 | (0.79–1.08) |

| 2002 | 1.03 | (0.98–1.09) | 1.30 | (1.18–1.44) | 0.91 | (0.78–1.07) |

| 2003 | 1.08 | (1.02–1.14) | 1.45 | (1.31–1.60) | 0.90 | (0.76–1.06) |

| 2004 | 1.09 | (1.03–1.15) | 1.51 | (1.37–1.66) | 0.98 | (0.83–1.15) |

| 2005 | 1.08 | (1.02–1.14) | 1.68 | (1.51–1.88) | 1.02 | (0.87–1.19) |

| 2006 | 1.09 | (1.03–1.15) | 1.84 | (1.68–2.02) | 1.10 | (0.94–1.28) |

| 2007 | 0.95 | (0.89–1.00) | 1.99 | (1.81–2.19( | 1.29 | (1.11–1.49) |

| 2008 | 0.96 | (0.90–1.03) | 2.10 | (1.91–2.31) | 1.53 | (1.32–1.77) |

| 2009 | 1.01 | (0.95–1.07) | 2.34 | (2.12–2.58) | 1.81 | (1.57–2.08) |

| 2010 | 1.04 | (0.98–1.11) | 2.51 | (2.28–2.76) | 1.62 | (1.39–1.88) |

| 2011 | 1.06 | (0.99–1.13) | 2.82 | (2.54–3.12) | 2.04 | (1.76–2.35) |

| Household income | ||||||

| Lowest quartile | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Second quartile | 0.99 | (0.98–1.01) | 0.96 | (0.94–0.98) | 0.99 | (0.93–1.05) |

| Third quartile | 0.99 | (0.98–1.01) | 0.90 | (0.87–0.93) | 0.95 | (0.88–1.02) |

| Highest quartile | 0.97 | (0.95–0.99) | 0.87 | (0.84–0.90) | 0.94 | (0.86–1.02) |

| Unknown | 1.05 | (0.99–1.11) | 1.03 | (0.94–1.12) | 1.00 | (0.83–1.21) |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| Medicare | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Medicaid | 1.04 | (0.98–1.11) | 0.73 | (0.67–0.79) | 0.83 | (0.65–1.07) |

| Private | 1.00 | (0.95–1.07) | 0.58 | (0.54–0.63) | 0.68 | (0.53–0.86) |

| Self pay | 1.04 | (0.97–1.11) | 0.81 | (0.74–0.89) | 0.79 | (0.60–1.04) |

| Other | 1.05 | (0.98–1.12) | 0.67 | (0.61–0.74) | 0.66 | (0.50–0.86) |

| Unknown | 1.01 | (0.90–1.13) | 0.71 | (0.60–0.84) | 0.75 | (0.41–1.36) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Black | 1.06 | (1.03–1.09) | 1.48 | (1.44–1.53) | 1.55 | (1.43–1.68) |

| Hispanic | 1.25 | (1.22–1.28) | 1.33 | (1.29–1.37) | 1.19 | (1.09–1.29) |

| Other | 1.23 | (1.20–1.27) | 1.31 | (1.27–1.36) | 1.58 | (1.46–1.71) |

| Unknown | 1.01 | (0.96–1.06) | 1.07 | (1.02–1.14) | 0.95 | (0.87–1.04) |

| Hospital bed size | ||||||

| Small | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Medium | 0.99 | (0.92–1.06) | 0.99 | (0.89–1.09) | 1.04 | (0.92–1.17) |

| Large | 0.91 | (0.85–0.97) | 0.86 | (0.87–1.06) | 1.13 | (1.01–1.27) |

| Unknown | 0.80 | (0.61–1.06) | 0.56 | (0.26–1.23) | 0.82 | (0.40–1.70) |

| Hospital Location | ||||||

| Rural | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Urban | 1.33 | (1.24–1.42) | 1.14 | (1.05–1.25) | 0.92 | (0.82–1.04) |

| Hospital Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Midwest | 1.15 | (1.06–1.25) | 0.89 | (0.79–1.01) | 1.01 | (0.90–1.14) |

| South | 0.83 | (0.76–0.91) | 0.99 | (0.90–1.10) | 1.00 | (0.90–1.12) |

| West | 1.21 | (1.11–1.32) | 0.88 | (0.78–0.99) | 1.27 | (1.13–1.43) |

| Hospital Teaching | ||||||

| Non-teaching | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Teaching | 0.95 | (0.88–1.02) | 0.84 | (0.77–0.92) | 0.78 | (0.71–0.85) |

All data are presented as adjusted risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Three individual models were created for (i) all postpartum hemorrhage, (ii) hemorrhage associated with blood transfusion and (iii) maternal morbidity associated with postpartum hemrorhage and/or blood transfusion

Calculation of the AUC for the ROC curves demonstrated varying accuracy for the outcomes assessed. The accuracy of the log linear random-intercept model was poor for hemorrhage (receiver operator characteristic area under the curve (ROC AUC) 0.618, 95% CI 0.617–0.619), fair for transfusion (AUC 0.776, 95% CI 0.774–0.778), and good for severe morbidity 0.820 (95% CI 0.814–0.824). Sensitivity analyses for the ROC curves including only fixed effects log-linear regression models and excluding center clustering demonstrated similar results: an AUC of 0.626 for hemorrhage (95%CI 0.624–0.627), 0.776 for transfusion (95% CI 0.774–0.778), and 0.820 for severe morbidity (95% CI 0.815–0.825). Finally the random intercept models were repeated and the ROC AUC was calculated individually for each of the volume categories for the outcomes of hemorrhage, transfusion and severe morbidity. For hemorrhage, accuracy was poor for low (AUC 0.637, 95% CI 0.635–0.639), medium (AUC 0.633, 95% CI 0.631–0.635), and high volume hospitals (AUC 0.625, 95% CI 0.624–0.627). For transfusion, accuracy was fair for low (AUC 0.751, 95% CI 0.747–0.755), medium (AUC 0.779, 95% CI 0.775–0.782), and high volume hospitals (AUC 0.788, 95% CI 0.785–0.790). For severe morbidity accuracy was fair for low volume hospitals (AUC 0.782, 95% CI 0.768–0.800), and good for medium (AUC 0.831, 95% CI 0.0.821–0.841) and high volume hospitals (AUC 0.826, 95% CI 0.819–0.831).

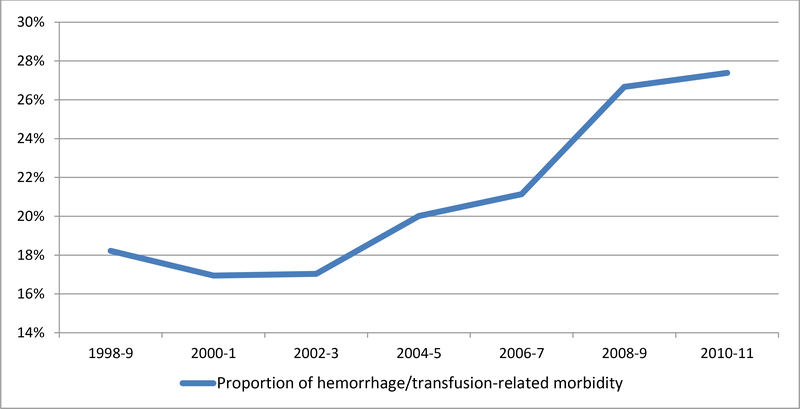

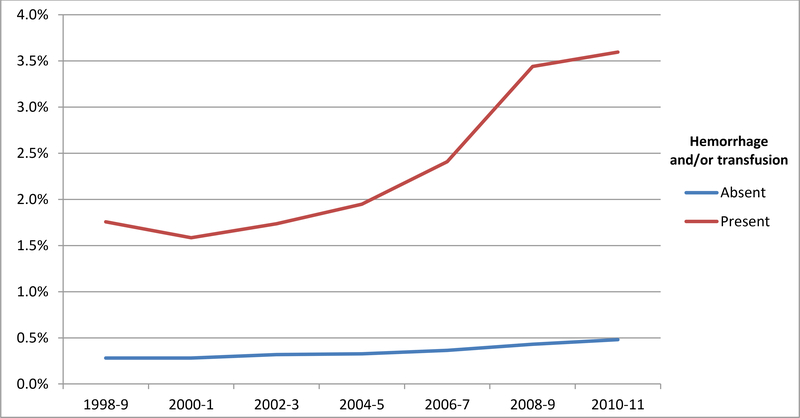

The proportion of severe maternal morbidity associated with hemorrhage and/or transfusion for the entire cohort of 55,140,088 deliveries is demonstrated in Figure 2A. Over the study period, the proportion of transfusion/hemorrhage-related morbidity rose accounting for 18.2% of overall morbidity in 1998–9 compared to 27.3% in 2010–1. Over this same period, absolute risk for severe morbidity during delivery hospitalizations both with and without a diagnosis of hemorrhage and/or transfusion increased (Figure 2B). Risk for morbidity for women without transfusion or hemorrhage rose from 0.25% in 1998 to 0.53% in 2011 while for women with a diagnosis of hemorrhage and/or transfusion, severe morbidity risk rose from 1.85% in 1998 to 3.98% in 2011.

Figure 2A. Proportion of severe maternal morbidity in the entire cohort associated with a diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage and/or receipt of transfusion.

Legend. Figure 2A demonstrates a temporal rise in hemorrhage/transfusion-related morbidity as a proportion of all morbidity over the study period.

Figure 2B. Risk of severe morbidity with and without a diagnosis of hemorrhage and/or transfusion.

Legend. Figure 2B demonstrates rates of severe morbidity for women with and without a diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage and/or transfusion.

DISCUSSION

This analysis of a nationally representative sample of delivery hospitalizations demonstrated several clinically important findings related to postpartum hemorrhage and hospital volume. First, while risk of hemorrhage and transfusion were similar across hospital volume categories, over the study period there were temporal increases in risk for transfusion and hemorrhage-related morbidity. These findings support the need to improve care for postpartum hemorrhage for all hospitals providing care, not just at large referral centers. Research has demonstrated that low-volume hospitals are less likely to have hemorrhage protocols19 and these centers may represent an important focus for quality improvement. Second, our models reveal that while observed factors were poor in predicting the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, they were useful in predicting transfusion and hemorrhage-related morbidity across all hospital volume categories. Given that risk for transfusion and/or morbidity may be anticipated,20,21 these results support the use of routine hemorrhage risk assessment for all centers providing obstetric care.8 These findings agree with prior studies that have demonstrated that hemorrhage risk assessment tools are of limited sensitivity and specificity in detecting hemorrhage overall;21 however, given that our models better discriminated the riskiest hemorrhage cases - those that result in severe morbidity, transfusion, or both – our analysis suggests an important role for hemorrhage risk-factor assessment. Risk assessment may allow for preparation for patients at highest risk for transfusion and hemorrhage/transfusion related morbidity, as well as transfer and triage of the riskiest patients. Timely diagnosis and appropriate responses to large hemorrhage may improve outcomes. Third, temporal trends in transfusion and hemorrhage-related morbidity were discordant from those of postpartum hemorrhage. Given this finding and that the diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage is based on a subjective clinical estimation of blood loss and varies based on whether vaginal or cesarean delivery occurred, evaluating transfusion and hemorrhage-related morbidity may provide a more better estimate of severe hemorrhage and thus the maternal burden posed by this complication.

There are several important considerations in how the findings from this analysis may relate to care quality for obstetric hemorrhage. First, it is unclear whether protocols for postpartum hemorrhage reduce risk for the event; observational research has demonstrated that rates of hemorrhage may be similar in centers with and without hemorrhage-specific protocols.22 The benefit of care quality improvements for hemorrhage management may reside in early detection of and timely response to hemorrhage as opposed to prevention. While death from hemorrhage has decreased based on surveillance data from the Centers from Disease Control and prevention, further reductions may still be possible.1 Second, it is unclear how rising transfusion rates are related to care quality. While it is possible that optimal management of postpartum hemorrhage may reduce the need for transfusion,23 improved care with an increased awareness of hemorrhage risk factors and better blood product availability could also lead to increased transfusion. Research suggests that preparedness for hemorrhage including the availability of hemorrhage protocols and the use of routine risk assessment varies significantly on a hospital basis;24 thus the rising rate of blood product use in this study may be a result of appropriate, high quality care, poor quality care, or both. Hospital level assessment with chart review and evaluation of hemorrhage guidelines is required to properly assess care quality Finally, for the most severe cases of postpartum hemorrhage that may involve risk for maternal death, it is unclear to what degree morbidity such as acute renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and pulmonary edema may be completely preventable; ultimately national improvements in hospital-level management of hemorrhage may be best reflected in decreased risk of death.

In interpreting the results of this study there are several important limitations. First, in evaluating the relationship between hemorrhage and morbidity, given that this analysis was performed with billing data we were not able to establish causality by chart review. It is possible that in individual cases, a patient could have had postpartum hemorrhage and severe morbidity attributable to a separate, unrelated etiology or complication. However, a number of findings support increasing morbidity specifically in the setting of hemorrhage: (i) absolute risk for morbidity in the setting of hemorrhage increased well beyond the temporal rise in risk for the general population, (ii) the proportion of overall morbidity associated with transfusion/hemorrhage increased during the study period, and (iii) the most common severe morbidity diagnoses associated with hemorrhage/transfusion – DIC, shock, acute renal failure, acute respiratory failure, pulmonary edema – are sequelae of severe hemorrhage. A second limitation is that ancillary ICD-9 coding may be driven by reimbursement policies with codes that carry higher reimbursement or that carry more significant clinical implications more likely to be reported.25 Severe maternal complications and required blood transfusions may be more likely to be reported in comparison to postpartum hemorrhage alone; this may bias our model towards underestimating the prevalence of this diagnosis relative to the others. Third, although the NIS has several strengths as a data set including a geographically diverse, nationally representative sample, it is limited by the variables included in the data set. For example, there may be other hospital factors beyond region, bed size and teaching status that are important in relation to the outcomes being studied that cannot be included in the analysis. Other relevant characteristics such as body mass index and parity are also not included in the NIS. Furthermore, because the NIS does not include data on drug and device use and details of clinical management, this analysis is not able to review how clinical practice and hospital culture affects outcomes. Additionally, some covariates such as anemia on admission were not included given that the validity of these diagnoses is unclear during pregnancy when dilutional anemia may routinely occur. Fourth, classification of annualized hospital delivery volume categories are somewhat arbitrary; we utilized a cutoff of ≤1000 deliveries per year for low volume centers given the clinical interpretability of this cutoff and that it approximately represents the 20% of deliveries occurring in the lowest volume center. Other analyses have used other varying cutoffs3,26 and given that resources may be modest for hospitals with very low volume (<500 deliveries per year) future analyses may be indicated for these centers. Fifth, given that billing data is submitted after a hospitalization, and some risk only becomes clinically apparent during labor or after delivery, risk stratification must be considered a dynamic process throughout the hospital stay. Finally, the NIS does not link patient readmissions across hospitals, so evaluation of women who were discharged and then readmitted with delayed postpartum hemorrhage is not possible. Strengths of this study include the ability to model an estimate of the national population and a 14-year assessment period.

In summary, given that blood transfusion and transfusion/hemorrhage-related maternal morbidity are increasing across hospital volume categories, there is an urgent need to improve maternal care for hemorrhage for all centers providing obstetrical care. That risk-factor base models are able to successfully discriminate women at increased risk for transfusion and morbidity across volume settings supports routine hemorrhage risk assessment.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Friedman is supported by a career development award (K08HD082287) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callaghan WM. Overview of maternal mortality in the United States. Seminars in perinatology 2012;36:2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:449 e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman BT, Berman MF, Riley LE, Leffert LR. The epidemiology of postpartum hemorrhage in a large, nationwide sample of deliveries. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oyelese Y, Ananth CV. Postpartum hemorrhage: epidemiology, risk factors, and causes. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010;53:147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischer A, Meirowitz N. Care bundles for management of obstetrical hemorrhage. Seminars in perinatology 2016;40:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg CJ, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, et al. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: results of a state-wide review. Obstetrics and gynecology 2005;106:1228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Herbst MA, Meyers JA, Hankins GD. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:36 e1–5; discussion 91–2 e7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National Partnership for Maternal Safety: Consensus Bundle on Obstetric Hemorrhage. Obstetrics and gynecology 2015;126:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology 2013;122:233–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Maternal and child health journal 2008;12:469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman BT BM, Riley LE, Leffert LR. The Epidemiology of Postpartum Hemorrhage in a Large, Nationwide Sample of Deliveries. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Development of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients. Obstetrics and gynecology 2013;122:957–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991–2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:133 e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snowden JM, Cheng YW, Emeis CL, Caughey AB. The impact of hospital obstetric volume on maternal outcomes in term, non-low-birthweight pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:380 e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janakiraman V, Lazar J, Joynt KE, Jha AK. Hospital volume, provider volume, and complications after childbirth in U.S. hospitals. Obstetrics and gynecology 2011;118:521–7. 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gynecologists ACoOa. Postpartum Hemorrhage. ACOG Practice Bulletin 2006;76:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant AMJ, Leffert LR, Hoban RA, Yakoob MY, Bateman BT. The Association of Maternal Race and Ethnicity and the Risk of Postpartum Hemorrhage. Anesth Analg 2012;115:1127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mhyre JM SA, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kaminsky S, Bateman BT. Massive Blood Transfusion During Hospitalization for Delivery in New York State, 1998–2007. Obstetrics and gynecology 2013;122:1288–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kacmar RM, Mhyre JM, Scavone BM, Fuller AJ, Toledo P. The use of postpartum hemorrhage protocols in United States academic obstetric anesthesia units. Anesth Analg 2014;119:906–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu E, Jolley JA, Hargrove BA, Caughey AB, Chung JH. Implementation of an obstetric hemorrhage risk assessment: validation and evaluation of its impact on pretransfusion testing and hemorrhage outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015;28:71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dilla AJ, Waters JH, Yazer MH. Clinical validation of risk stratification criteria for peripartum hemorrhage. Obstetrics and gynecology 2013;122:120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailit JL, Grobman WA, McGee P, et al. Does the presence of a condition-specific obstetric protocol lead to detectable improvements in pregnancy outcomes? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:86 e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butwick AJ, Carvalho B, Blumenfeld YJ, El-Sayed YY, Nelson LM, Bateman BT. Second-line uterotonics and the risk of hemorrhage-related morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:642 e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingham D, Scheich B, Byfield R, Wilson B, Bateman BT. Postpartum Hemorrhage Preparedness Elements Vary Among Hospitals in New Jersey and Georgia. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016;45:227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarrazin MSV RG. Finding pure and simple truths with administrative data. JAMA 2012;307:1433–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyser KL, Lu X, Santillan DA, et al. The association between hospital obstetrical volume and maternal postpartum complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:42 e1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]