Abstract

This study was conducted to evaluate the effects of different levels of dietary phytase supplementation in the layer feed on egg production performance, egg shell quality and expression of osteopontin (OPN) and calbindin (CALB1) genes. Seventy-five White Leghorn layers at 23 weeks of age were randomly divided into 5 groups consisting of a control diet with 0.33% non-phytate phosphorus (NPP) and 4 low phosphorus (P) diets: 2 diets (T1 and T2) with 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase or commercial phytase and another 2 diets (T3 and T4) with 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase or commercial phytase with complete replacement of inorganic P. The results indicated that there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in egg production performance and quality of egg during the first 2 months of trial. However, in next 2 months, a significant drop in egg production and feed intake was observed in birds fed diets with low P and 500 FTU/kg supplementation of laboratory produced phytase. Osteopontin gene was up-regulated whereas the CALB1 gene was down regulated in all phytase treatment groups irrespective of the source of phytase. The current data demonstrated that 250 FTU/kg supplementation of laboratory produced phytase with 50% less NPP supplementation and 500 FTU/kg supplementation of commercial phytase even without NPP in diet can maintain the egg production. The up-regulation of OPN and down regulation of CALB1 in egg shell gland in the entire phytase treated group birds irrespective of the source of enzymes is indicative of the changes in P bio-availability at this site.

Keywords: Phytase, Layer, Egg production, Gene expression, Egg shell

1. Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is a major and essential mineral for all animals and is involved directly or indirectly in all physiological functions and also a component of large co-enzymes (Anselme, 2003). To reduce excess P excretion and better utilization, phytase enzyme is supplemented for maintaining optimum economical poultry production. Laying birds require high calcium (Ca) level for egg shell deposition and bone maintenance (Pizzolante et al., 2009). Both minerals are most crucial during the laying period (De Vries et al., 2010). The Ca and P levels in the diet also influence the eggshell formation which in turn linked with quality of egg in the laying birds.

The levels of Ca and P control the expressions of genes and these products involved in physical and chemical parameters of the calcification processes. The osteopontin (OPN) comprises of a polyaspartic acid sequence, sites of Ser/Thr phosphorylation that mediate hydroxyapatite binding, and 2 highly conserved tripeptide arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid (RGD) motifs in the chicken that mediate cell attachment/signaling (Sodek et al., 2000). Additionally, OPN shows other post-translational modifications such as glycosylation and sulfation for metabolism and other functions. This phosphoprotein is found in the eggshell and the gene expressed in egg shell gland (ESG) of chicken (Fernandez et al., 2003; Mann et al., 2007). In the chicken, uterine expression of the OPN gene is temporally associated with eggshell mineralization through a coupling of physical expansion of the uterus with OPN gene expression (Lavelin et al., 2000). Calbindin (CALB1) on the other hand is a 28 kDa calcium binding protein (Chard et al., 1993), which was found in the ESG, and predominantly a Ca2+ dependent protein and related to eggshell quality (Nys et al., 1989, Bar et al., 1992). The presence of CALB1 in the shell gland mucosa of laying hens increases with the onset of egg production, and it decreases as egg production ceases (Corradino et al., 1968).

Keeping the above background in mind the current study was designed to understand the comparative efficacy of low P diets supplemented with laboratory produced phytase derived from fungal and commercially available phytase which is derived from microbes especially recombinant bacteria on egg production and egg shell quality; and the effects of different diets on expression of the CALB1 and OPN genes in layer chicken. The study was also to test whether laboratory produced phytase was of similar efficacy as that of commercial phytase.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design and diets

Seventy-five White Leghorn layer birds at 15 weeks of age were procured from a commercial layer farm, housed in individual laying cages fitted with individual feeder and water supply. The cages were illuminated with 24-h lighting. Birds were fed standard diets till 22 weeks of age and then shifted to experimental diets by 23 weeks of age when all the birds were in peak egg production. Birds were randomly assigned to 5 treatment groups and each treatment group had 15 replicates. Dietary treatment groups consisted of a control diet with 0.33% non-phytate phosphorus (NPP) and 4 low P diets: 2 treatment diets (T1 and T2) with 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase or commercial phytase and another 2 treatment diets (T3 and T4) with 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase or commercial phytase with complete replacement of inorganic P. All the birds were offered feed ad libitum during the entire 17-wk experimental period. The composition of diet and the nutrient content for the experimental layers are given in Table 1. The experimental diet contained 2600 ME (kcal/kg), 17% CP and 3.5% Ca in all the groups.

Table 1.

Ingredient and nutrient composition of the experimental layer diet (DM basis).1

| Item | Control | T1 and T2 | T3 and T4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient, % | |||

| Maize | 57.75 | 57.75 | 57.95 |

| Soybean meal | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| De oiled rice bran | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Limestone | 7.61 | 8.11 | 8.41 |

| Salt (NaCl) | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.0 | 0.5 | – |

| DL-methionine | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Trace mineral and vitamin premix2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Nutrient composition, % | |||

| ME,3 kcal/kg | 2,614 | 2,614 | 2,620 |

| CP | 17.1 | 17.1 | 17.1 |

| Ca | 3.53 | 3.50 | 3.42 |

| Total P | 0.632 | 0.552 | 0.472 |

| Phytate P | 0.308 | 0.308 | 0.308 |

| Available P3 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.16 |

| Lysine | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Methionine | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Threonine | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

Control = 0.33% non-phytate phosphorus (NPP); T1 = 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T2 = 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg commercial phytase; T3 = 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T4 = 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg commercial phytase.

Trace mineral premix, 1 g/kg; vitamin premix, 1 g/kg and choline, 0.5 g/kg. Trace mineral premix supplied mg/kg diet: Mg, 300; Mn, 55; I, 0.4; Fe, 56; Zn, 30; Cu, 4. Vitamin premix supplied per kg diet: vitamin A, 8250 IU; vitamin D3, 30 mg; vitamin K, 1 mg; vitamin E, 40 IU; vitamin B1, 2 mg; vitamin B2, 4 mg; vitamin B12, 0.01 mg; niacin, 60 mg; pantothenic acid, 10 mg.

Calculated values.

2.2. Phytase for feeding trail

Laboratory produced phytase was produced by immobilization of Aspergillus awamori NCIM 885 strain procured from National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms, Pune following the technique of Lalpanmawia et al. (2014). The crude phytase enzyme obtained from fungal fermentation was filtered, clarified by centrifugation at 5590 × g for 15 min and precipitated from the media by 90% saturation of ammonium sulfate salts. The pellet obtained was dissolved in 0.2 mol/L sodium acetate buffer and respective FTU in the required volume was added in the measured layer diet and mixed uniformly. The commercial phytase (Escherichia coli derived product, 5000 FTU/g) was used for the present study. Phytase activity was determined as per the protocol described by Kim and Lei (2005) and phytate as per Haug and Lantzsch (1983). The Ca and P in feed were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy ICP–OES using a Perkin Elmer instrument.

2.3. Egg production, egg weight and egg shell quality

Egg productions were recorded daily on individual basis. Daily weighed amount of feed was added and residue was recorded every 4 wk interval. Eggs of each bird were taken and weighted twice a week whereas the eggshell weight and the thickness were determined individually at 2-week intervals. Thickness of the eggshells was measured at 3 different locations (middle, broad and narrow end) using a micrometer gauge.

2.4. Collection of eggshell gland tissue samples

The birds were daily monitored for any leg weakness, lameness, etc. At the end of the trial, 6 hens per treatment group were sacrificed after egg production by cervical dislocation. Egg shell glands from the birds were detached from the oviduct, the bulbous were opened, and the inner layer was scraped with sterile micro slides and collected in the micro centrifuge tube containing 0.5 mL RNA later (Sigma Aldrich Cat No. R0901-100ML). Tissue samples were stored at 4 °C overnight and then stored at −80 °C for future use.

2.5. Isolation of total RNA and quality assessment

Total RNA was extracted from minimum 3 randomly selected tissue samples of ESG from each group using TRI Reagent (Sigma Aldrich, TRI Reagent BD Cat #T9424) according to the manufacturer's instruction. About 60 to 100 mg tissue samples in 1 μL TRI Reagent were homogenized in 2 μL micro centrifuge tubes and processed. The total RNA yields and purity were determined using NanoDrop ND-2000 UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Czech Republic) by the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. The integrity of denatured RNA was determined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.2 mol/L 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (pH 7.0). One microgram of sample with one volume of 5 × denaturing buffer were mixed properly and denatured at 60 °C for 10 min.

2.6. Synthesis of single stranded cDNA from total RNA samples

The cDNA from 4 μg total RNA was synthesized by reverse transcription (RT) using RevertAid minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, Catalog No. K1621) following manufacturers protocol. The cDNA was diluted to 100 ng/μL stock and stored frozen at −80 °C until use.

2.7. Design and synthesis of qPCR primers and determination of primer efficiency

Primers for the endogenous control β-actin and the test genes CALB1 and OPN were designed using Primer 3 web tool (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/primer3/) input software (Table 2).

Table 2.

qPCR primers of endogenous control (β-actin) and test genes osteopontin and calbindin used for relative quantification of gene expression with their melt temperature (Tm), GC content and amplicon sizes.

| Genes | Accession No. | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Tm, °C | GC, % | Size, bp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | NM_205518.1 | Left | AGAGCTATGAACTCCCTGATGG | 54.8 | 50 | 106 |

| Right | CCACAGGACTCCATACCCAAG | 56.3 | 57.1 | |||

| Osteopontin | NM_204535.4 | Left | AAGAGGCCGTGGATGATGATG | 54.36 | 52.38 | 254 |

| Right | ATCCTCAATGAGCTTCCTGGC | 54.36 | 52.38 | |||

| Calbindin | NM_205513.1 | Left | CTCCGACGGCAATGGGTAC | 55.4 | 63.2 | 96 |

| Right | GGTGTTAAGTCCAAGCCTGCC | 56.3 | 57.1 |

The efficiency of the endogenous control and test gene assays were determined in 5 folds serially diluted cDNA template starting from 50 to 0.4 ng in duplicate with triplicate non template control (NTC) and negative RT (diluted RNA). The calculated efficiency of endogenous control gene β-actin, OPN and CALB1 was 2.02, 2.03 and 1.93, respectively.

2.8. Relative expression analysis of CALB1 and OPN by qPCR

The relative expression of the chicken eggshell gland OPN and CALB1 genes was measured by SYBR green based qPCR. In brief, the PCR amplification of endogenous control and the test genes were performed in triplicate 10 μL reaction mixtures containing 4 μL template (10 ng cDNA), 0.5 μL of 2.5 μmol/L each forward and reverse primers, 5 μL of 2 × Fast Start SYBR Green master mix (Roche, Cat. No. 6924204001) for the sample (+RT), 10 ng total RNA for non-reverse transcriptase (-RT) and water for NTC.

The reaction was performed in Light Cycler 480 Instrument using Light Cycler 480 Multiwell plate 96; clear (Roche, Cat. No. 05102413001). The PCR cycling condition was comprised of 95 °C for 3 min initial denaturation followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 15 s; and 60 to 97 °C for melting curve analysis. Target gene expression relative to β-actin level was determined by the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method as described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data on egg production, egg quality and relative expression of test genes were subjected to one-way analysis of variance for completely randomized design and tested for significance between the dietary treatments means (SPSS, 2010 Version 18.0). The values were significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Egg laying performance, egg weight and egg shell quality

The egg production performance remained the same (P > 0.05) during the first 2 months of trial from 23 to 31 weeks. There was a significant drop in egg production and feed intake during 32 to 40 weeks in birds fed diets with low P and laboratory produced phytase at 500 FTU/kg (Table 3). In the other 3 groups, the production performance remained unchanged. The results of this study indicated that laboratory produced phytase at 250 FTU/kg was able to replace 0.7% NPP supplementation whereas the commercial phytase at 500 FTU/kg was able to replace whole of inorganic P in layer diet. Feed conversion ratio was better (P < 0.05) in the diets with low P and laboratory produced phytase at 500 FTU/kg probably due to lower feed intake in this group. Egg quality in terms of egg weight, eggshell weight and shell thickness did not differ (P > 0.05) during 23 to 31 weeks and 32 to 40 weeks of laying among the treatment groups (Table 4).

Table 3.

Egg production performance of commercial layers into 2 phases from 23 to 31 wk and 32 to 40 wk.

| Groups1 | Egg production, % |

Feed intake, g/bird |

FCR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 to 31 wk | 32 to 40 wk | 23 to 31 wk | 32 to 40 wk | 23 to 31 wk | 32 to 40 wk | |

| Control | 93.4 | 96.6a | 100.8 | 106.6a | 2.04 | 1.95a |

| T1 | 90.1 | 96.4a | 99.9 | 106.7a | 2.01 | 1.91a |

| T2 | 93.5 | 96.5a | 102.2 | 108.4a | 2.09 | 1.97a |

| T3 | 90.3 | 73.6b | 102.1 | 96.7b | 1.98 | 1.83b |

| T4 | 95.5 | 98.3a | 105.7 | 108.1a | 2.06 | 1.97a |

| SEM | 0.94 | 1.598 | 0.87 | 0.899 | 0.016 | 0.017 |

| P-value | 0.318 | 0.001 | 0.296 | 0.001 | 0.191 | 0.045 |

FCR = feed conversion ratio; SEM = standard error of mean.

a,b Different letters indicate significant difference within columns (P < 0.05).

Control = 0.33% non phytate phosphorus (NPP); T1 = 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T2 = 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg commercial phytase; T3 = 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T4 = 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg commercial phytase.

Table 4.

Egg quality of commercial layers into 2 phases from 23 to 31 wk and 32 to 40 wk.

| Groups1 | Egg weight, g |

Shell weight, mm |

Shell thickness, mm |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 to 31 wk | 32 to 40 wk | 23 to 31 wk | 32 to 40 wk | 23 to 31 wk | 32 to 40 wk | |

| Control | 51.5 | 54.7 | 10.3 | 10.25 | 0.382 | 0.363 |

| T1 | 51.9 | 56.2 | 9.7 | 10.25 | 0.37 | 0.368 |

| T2 | 50.5 | 55.1 | 10.5 | 10.15 | 0.388 | 0.362 |

| T3 | 49.9 | 53.07 | 10.4 | 9.15 | 0.393 | 0.328 |

| T4 | 52 | 55.05 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 0.393 | 0.365 |

| SEM | 0.32 | 0.374 | 0.13 | 0.177 | 0.0048 | 0.006 |

| P-value | 0.138 | 0.126 | 0.284 | 0.077 | 0.534 | 0.118 |

SEM = standard error of mean.

Control = 0.33% non phytate phosphorus (NPP); T1 = 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T2 = 0.24% NPP + 250 FTU/kg commercial phytase; T3 = 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T4 = 0.16% NPP + 500 FTU/kg commercial phytase.

3.2. Morbidity of birds

Few birds in T3 were observed with leg disorders followed by low feed intake and drop in egg production for few days. However, they recovered from the problem but with lower egg production.

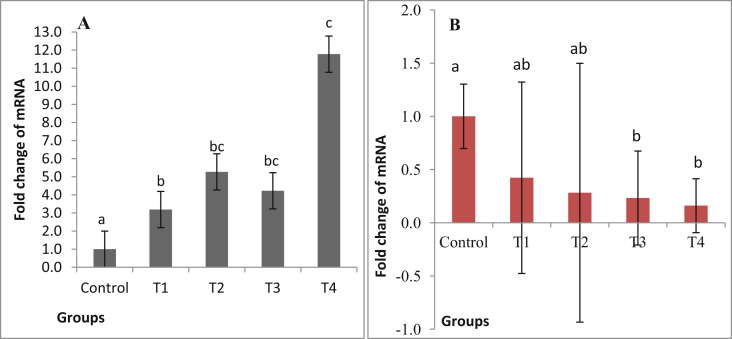

3.3. Changes in relative expression of OPN and CALB1 in eggshell gland

The relative expression of OPN genes was found up-regulated (P < 0.05) in the birds of all the treatment groups supplemented with the commercial and laboratory produced phytases at the level of 500 and 250 FTU/kg feed as compared to the control which were supplemented with the recommended level of NPP. The maximum of 11.78 folds up-regulation was observed in group supplemented with commercial phytase at the level of 500 FTU/kg feed (T4).

The expression of CALB1 was found significantly down regulated (P < 0.05) birds supplemented with either laboratory produced (T3) or commercial (T4) phytase at the rate of 500 FTU/kg feed. The down regulation of this gene expression was not observed in the 2 other groups of birds fed 50% less phytase and 50% less NPP.

Interestingly the birds supplemented with commercial phytase at 500 FTU/kg showed the highest up regulation of OPN and the maximum down regulation of CALB1 gene (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of dietary non phytate phosphorus (NPP) level and phytase supplementation on relative expression of (A) osteopontin (OPN) and (B) calbindin (CALB1) mRNA in eggshell glands. The bars (means ± SEM) with different letters (a, b, c) showed significant differences at P ≤ 0.05. Control = 0.33% NPP; T1 = 0.24%NPP + 250 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T2 = 0.24%NPP + 250 FTU/kg commercial phytase; T3 = 0.16%NPP + 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase; T4 = 0.16%NPP + 500 FTU/kg commercial phytase.

4. Discussion

The declined egg production in 500 FTU/kg laboratory produced phytase treatment group was associated with significantly lower feed intake of the birds. The lower feed intake coupled with imbalance of Ca and P intake might have caused the lameness in few birds. However, the birds recovered from the lameness by decreasing the production performance, acclimatizing for the lower P intake. The reason for the lower feed intake is the lower inorganic P availability. The feed intake was not affected in lower dose (250 FTU/kg) of laboratory produced phytase and the higher dose (500 FTU/kg) of the same organism phytase (Jalal and Scheideler, 2001). The commercial phytase at the level of 500 FTU/kg also did not produce similar effect on feed intake in birds. In another study, 500 U/kg phytase supplemented with no inorganic P diet showed similar feed intake compared to treatment containing inorganic P of about 0.14% to 0.19% (Yao et al., 2007). Maintenance of similar production performance and the feed conversion efficiency in birds supplemented with 500 FTU/kg commercial phytase without NPP (T4) and the control group birds which were maintained with only NPP (control) indicated that supplementation of 500 FTU/kg of phytase has the capacity to replace the whole of inorganic P from layer diet. On the contrary, several other reports recommended the partial replacement of inorganic P by phytase supplementation in diets. Panda et al. (2005) described that addition of 500 FTU/kg of microbial phytase can reduce the low level of NPP around 1.2 g/kg in the layer diet. Similarly Tischler et al. (2015) reported that there was no difference between the production intensity of hens fed diets with recommended 2.45 g/kg NPP and 50% reduced NPP (2.15 g) + 300 FTU/kg feed. Zyla et al. (2011) showed egg production and feed intake had no influence on low NPP diets (0.12%) in presence of phytase B at 2.5 AcPU/kg (1 unit of phytase B activity [AcPU] was equal to 1 μmol/L per min of p-nitrophenol liberated from 5.5 mmol/L disodium p-nitrophenylphosphate at 40 °C, pH 4.5) and adequate Ca (2.8% or 3.8%). Although the production performance did not change in our study, Jalal and Scheideler (2001) reported that phytase supplementation has beneficial effects on the performance of egg laying in hens. They also reported that supplementation of commercial phytase (250 and 300 FTU/kg) with low 0.10% NPP diet improved feed intake, feed conversion and egg mass, and elicited a positive response in eggshell quality. One probable reason is that the commercial phytase could be used safely in layer diets without any effect on feed intake and production performance as the protein is produced by recombinant DNA technology and is active on a wider pH range in the gut. Nevertheless, this experiment showed that the laboratory produced phytase from the native organism could replace 0.7% inorganic P in the treatment with 250 FTU/kg phytase containing 0.24% of NPP and it gives an indication that the fungal phytase is more active in the upper part of the gut at lower pH range. Feed conversion ratio of 1.86 in the treatment of 0.25% NPP without phytase was more efficient compared to 1.89 in the treatment with 0.10% NPP with phytase (Jalal and Scheideler, 2001). Liu et al. (2007) reported reduction of the NPP level from 0.28% to 0.15% significantly decreased egg production and there was no effect on FCR and egg weight. In contrast to our findings, Keshavarz (2003) found that phytase supplementation increased egg weight, and dietary NPP levels (0.15% to 0.40%) had no impact on feed intake in layers during 30 to 42 weeks of age. Cabuk et al. (2004) observed egg production was significantly increased (75.49% to 77.96% and 64.59% to 76.54%) when phytase was supplemented to the control diet at 4.5 g/kg and 3 g/kg (AP); feed intake was 95.24 g/d at low NPP level of 3 g/kg without phytase, whereas it was 101.69 g/d at the NPP level of 3 g/kg with phytase. Egg production of hens fed low NPP (0.24% or 0.12%) diets with 500 UP/kg was not significantly different from that of the control with high (0.37%) NPP (Um and Paik, 1999). Similarly, Gordon and Roland (1997) reported that low NPP content at 0.1% level with 300 FTU/kg phytase and high NPP content at 0.2% to 0.5% level without phytase had no difference in egg production. Boling et al. (2000) showed that 0.10% NPP was insufficient for maintaining egg production whereas 0.10% NPP + 300 U/kg phytase or 0.15% NPP without phytase supported optimum egg production throughout the experimental period. No change in eggshell weight, shell thickness and shell percentage was also reported with the increase in phytase supplementation at 0, 0.05%, 0.1% and 0.15% (Lucky et al., 2014). Mohammed et al. (2010) presented insignificant differences among treatments in egg quality measurements due to phytase supplementation to layers feed. Panda et al. (2005) and Cabuk et al. (2004) also reported there was no significant difference in eggshell weight and shell thickness among different levels of dietary NPP. Liu et al. (2007) showed Ca, P and phytase supplementation significantly improved eggshell thickness. Ziaei et al. (2009) and Lim et al. (2003) reported that low levels of Ca and AP in the dietary feed without phytase lead to lower egg shell weight in turn. Tischler et al. (2015) reported shell thickness was thinner affected by both dietary treatments and time.

Osteopontin is one of the phospho-protein detected in eggshell gland of oviduct (Pines et al., 1996, Mann et al., 2007), where immense calcification occurs. The presence of the egg in the uterus stimulates the gene expression of OPN (Brionne et al., 2014; Lavelin et al., 2000). Significant up regulation of OPN in all treatment groups compared to control might be due to the increased bioavailable P in eggshell gland. The increased level of P might trigger the expression of this protein which needs P for its function. To support the present findings, Katsumata et al. (2014) and Beck et al. (2000) observed that high P levels significantly increased OPN mRNA expression. The association between OPN expression and P levels modulates the Ca levels, suggesting OPN related to an overall role in regulating Ca localization or transport in conditions of high cellular P levels (Beck et al., 2000). In egg shell gland, the OPN is likely to regulate eggshell growth by inhibiting calcite growth at specific crystallographic faces (Chien et al., 2009, Hincke et al., 2008). Increased OPN expression in different doses of laboratory produced and commercial phytase might be the indications of increased bioavailability of P caused by the release of phytate P in the gut by the action of phytase in acidic pH that in turn made the P more bioavailability and maintain egg weight, egg shell weight and egg shell thickness similar to the control birds. The differences in the increase of fold changes in laboratory and commercial phytases might be attributable to the differences in preparation of the enzyme. In our study, the laboratory produced phytase was not capable enough to replace the phytate P completely, which in turn might have affected the P availability in the diet. As a normal phenomenon in the domestic hen, the expression of OPN mRNA gets up-regulated by the entry of the egg into the uterus and the associated mechanical strain upon the uterine wall (Lavelin et al., 2000) for egg shell calcification (Jeong et al., 2012). Present study suggested that decreasing level of dietary NPP and with increasing levels phytase affected the OPN expression in ESG. The increasing OPN level did not create abnormalities or crack in eggshell, and also did not change the egg production performance of birds in different treatment groups. The results supported the finding of Lavelin et al. (2000) that states OPN expression is independent of soft shell egg formation or any break on tip of eggs and that Arazi et al. (2009) stated over expression of OPN in uterus is not related to the abnormalities or cracks in eggshell.

Birds eggshell gland expresses a 28 kDa form of CALB1 in addition to the expression in other organs such as intestine, kidney and lung. In vitamin D receptor knockout mice model, it has been shown that the 28 kDa CALB1 is either expressed constitutively in kidney or dependent on vitamin D receptor binding as in intestine and lung (Li et al., 1998). The egg shell gland calbindin is synthesized in a circadian fashion (Christakos et al., 2007) and known as a facilitator of calcium diffusion (Li et al., 2012). The significant decrease of CALB1 expression increased with the increasing of OPN in all phytase treated groups of birds.

Calbindin level is expected to be down regulated uniformly after egg evacuation when the samples were collected. As compared to the control group birds, CALB1 expression was significantly down regulated in all phytase treatments probably due to the altered ratio of Ca to P in intestine, which might have affected the Ca flux which in turn down regulated the CALB1 among the treatment group birds in eggshell gland after the evacuation of eggs. Calbindin has the effect on buffer Ca level, meaning in low Ca its expression will be increased and in high Ca expression will be decreased. In broiler studies, Li et al. (2012) reported that birds fed normal P with low Ca diets or low dietary P with normal Ca diets caused up-regulated calbindin expression in intestine compared with the normal dietary Ca. In layer the expression of this gene fluctuates in egg shell gland during egg laying cycle depending on the need of Ca. Bar et al. (1992) reported a higher uterine calbindin activity during shell calcification in laying hens. Similarly, Nys et al. (1989) reported that the concentration of CALB1 mRNA in the shell gland of laying hens was low 4 h after ovulation and increased markedly 12 and 18 h later when shell calcification takes place. A significant 9-fold increased expression was of CALB1 observed in egg shell gland at 20 h after ovulation (Jeong et al., 2012). Since the collection of samples was done post laying, it is expected that CALB1 would remain down in all the treated and untreated birds. The reason for more down regulation of this gene in egg shell gland after egg laying in all phytase fed birds is not known. Calbindin acts as a dynamic Ca2+ buffer in Ca2+ transporting epithelia, and displays an important role in Ca2+ induced signal transmission (Lambers et al., 2006). Recent evidences suggest that CALB1 mediates the impact of dietary Ca on P absorption. In broiler chickens, calbindin mRNA was found affected by both Ca and dietary NPP (Li et al., 2011). In the present study, all diets of the different treatments had the same level of Ca, however, the expression of CALB1 was altered with the changes in supplementation of different formulation of phytases which is expected to release phytate P in the site of absorption.

The increased expression of OPN indicated an increased P availability in egg shell gland. Probably the increased P due to the action of phytase or the presence of varying levels of phytate in diet might have regulated the expression of CALB1 in all the treated groups of birds in a Ca independent fashion similar to the observation by Nie et al. (2013).

According to Arazi et al. (2009), normal shell calcification requires a very precise equilibrium between the expressions of OPN, CALB1, and probably various other genes among the matrix proteins synthesized by the ESG and that any deviation from this equilibrium will cause a specific shell abnormality. However, there is no difference in eggshell weight and thickness among the treatment groups in the present study and outcome also suggest that it might be affected by phytase source, dietary NPP level, and which in turn affected the Ca level in the layer body.

5. Conclusion

The current data demonstrated that 250 FTU/kg feed supplementation of laboratory phytase is capable of maintaining similar production and egg quality performance in layer birds with 50% less NPP supplementation. The commercial phytase at 500 FTU/kg feed supplementation can maintain the production and egg quality even without NPP in diet. The up-regulation of OPN and down regulation of CALB1 in egg shell gland in the entire phytase treated group irrespective of the source of enzymes are indicative of the changes in P bio-availability at this site. Understanding on the mechanisms needs a further detailed study.

Acknowledgment

The financial support received from Department of Biotechnology, Government of India is thankfully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Anselme P. Phosphorus in poultry nutrition. Key elements for performance and animal health. Feed Mag. 2003;1 March:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Arazi H., Yoselewitz I., Malka Y., Kelner Y., Genin O., Pines M. Osteopontin and calbindin gene expression in the eggshell gland as related to eggshell abnormalities. Poult Sci. 2009;88:647–653. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar A., Striem S., Vax E., Talpaz H., Hurwitz S. Regulation of calbindin messenger RNA and calbindin turnover in intestine and shell gland of the chicken. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R800–R805. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.5.R800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck G.R., Jr., Zerler B., Moran E. Phosphate is a specific signal for induction of osteopontin gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 2000;97:8352–8357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140021997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boling S.D., Douglas M.W., Johnson M.L., Wang X., Parsons C.M., Koelkebeck K.W. The effects of dietary available phosphorus level and phytase on performance of young and older laying hens. Poult Sci. 2000;79:224–230. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brionne A., Nys Y., Hennequet-Antier C., Gautron J. Hen uterine gene expression profiling during eggshell formation reveals putative proteins involved in the supply of minerals or in the shell mineralization process. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabuk M., Bozkurt M., Kirkpinar F., Ozku H. Effect of phytase supplementation of diets with different levels of phosphorus on performance and egg quality of laying hens in hot climatic conditions. South Afr J Anim Sci. 2004;24(1):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chard P.S., Bleakman D., Christakos S., Fullmer C.S., Miller R.J. Calcium buffering properties of calbindin D28K and parvalbumin in rat sensory neurons. J Physiol Lond. 1993;472:341–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y.C., Hincke M.T., McKee M.D. Avian eggshell structure and osteopontin. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:38–43. doi: 10.1159/000151374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakos S., Dhawan P., Benn B., Porta A., Hediger M., Oh G.T. Vitamin D: molecular mechanism of action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:340–348. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradino R.A., Wasserman R.H., Pubols M.H., Chang S.I. Vitamin D3 induction of a calcium-binding protein in the uterus of the laying hen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:378–380. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90674-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries S., Kwakkel R.P., Dijkstra J. Dynamics of calcium and phosphorus metabolism in laying hens. In: Vitti D.M.S.S., Kebreab E., editors. Phosphorus and calcium utilization and requirements in farm animals. CAB International; Wallingford, UK: 2010. pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M.S., Escobar C., Lavelin I., Pines M., Arias J.L. Localization of osteopontin in oviduct tissue and eggshell during different stages of the avian egg laying cycle. J Struct Biol. 2003;143:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R.W., Roland D.A. Performance of commercial laying hens fed various phosphorus levels, with and without supplemental phytase. Poult Sci. 1997;76:1172–1177. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.8.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug W., Lantzsch H.J. Sensitive method for the rapid determination of phytate in cereals and cereal products. J Sci Food Agric. 1983;34:1423–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Hincke M.T., Chien Y.C., Gerstenfeld L.C., McKee M.D. Colloidal-gold immunocytochemical localization of osteopontin in avian eggshell gland and eggshell. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:467–476. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.950576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal M.A., Scheideler S.E. Effect of supplementation of two different sources of phytase on egg production parameters in laying hens and nutrient digestibility. Poult Sci. 2001;80:1463–1471. doi: 10.1093/ps/80.10.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong W., Lim W., Kim J., Ahn S.E., Lee H.C., Jeong J.W. Cell-specific and temporal aspects of gene expression in the chicken oviduct at different stages of the laying cycle 1. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:172–180. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.098186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata S., Matsuzaki H., Katsumata-Tsuboi R., Uehara M., Suzuki K. Effects of high phosphorus diet on bone metabolism-related gene expression in young and aged mice. J Nutr Metab. 2014;10:1155. doi: 10.1155/2014/575932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz K. The effect of different levels of non-phytate phosphorus with and without phytase on performance of for strains of laying hens. Poult Sci. 2003;83:71–91. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.W., Lei X.G. An improved method for a rapid determination of phytase activity in animal feed. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:1062–1067. doi: 10.2527/2005.8351062x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalpanmawia H., Elangovan A.V., Sridhar M., Shet D., Ajith S., Pal D.T. Efficacy of phytase on growth performance, nutrient utilization and bone mineralization in broiler chicken. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2014;192:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers T.T., Mahieu F., Oancea E., Hoofd L., Lange F., Mensenkamp A.R. Calbindin-D28K dynamically controls TRPV5-mediated Ca2+ transport. EMBO J. 2006;25:2978–2988. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelin I., Meiri N., Pines M. New insight in eggshell formation. Poult Sci. 2000;79:1014–1017. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.7.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.H., Yuan J.M., Guo Y.M., Yang Y., Bun S.D., Hu X.F. The effect of dietary nutrient density on growth performance, physiological parameters, and small intestinal type IIb sodium phosphate co-transporter expression in broilers. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2011;2:102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.C., Pirro A.E., Demay M.B. Analysis of vitamin D-dependent calcium-binding protein messenger ribonucleic acid expression in mice lacking the vitamin D receptor. Endocrinology. 1998;139(3):847–851. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yuan J., Guo Y., Sun Q., Hu X. The influence of dietary calcium and phosphorus imbalance on intestinal NaPi-IIb and calbindin mRNA expression and tibia parameters of broilers. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2012;25:552–558. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2011.11266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H.S., Namkung H., Paik I.K. Effects of phytase supplementation on the performance, egg quality, and phosphorus excretion of laying hens fed different levels of dietary calcium and nonphytate phosphorus. Poult Sci. 2003;82:92–99. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Liu G.H., Li F.D., Sands J.S., Zhang S., Zheng A.J. Efficacy of phytases on egg production and nutrient digestibility in layers fed reduced phosphorus diets. Poult Sci. 2007;86:2337–2342. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2ΔΔC(T) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucky N.J., Howlider M.A.R., Alam M.A., Ahmed M.F. Effect of dietary exogenous phytase on laying performance of chicken at older ages. Bangladesh J Anim Sci. 2014;43(1):52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mann K., Olsen J.V., Macek B., Gnad F., Mann M. Phosphoproteins of the chicken eggshell calcified layer. Proteomics. 2007;7:106–115. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed K.H.A., Toson M.A., Hassanien H.H.M., Soliman M.A.H., El-nagar Sanaa HM. Effects of phytase supplementation on performance and egg quality of laying hens fed diets containing rice bran. Egypt Poult Sci. 2010;30(III):649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Nie W., Yang V., Yuan J., Wang Z., Guo Y. Effect of dietary nonphytate phosphorus on laying performance and small intestinal epithelial phosphate transporter expression in dwarf pink-shell laying hens. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2013;4:34. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nys Y., Mayel-Afshar S., Bouillon R., Van Baelen H., Lawson D.E. Increases in calbindin D 28K mRNA in the uterus of the domestic fowl induced by sexual maturity and shell formation. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1989;76:322–329. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(89)90164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda A.K., Rama Rao S.V., Raju M.V.L.N., Bhanja S.K. Effect of microbial phytase on production performance of white leghorn layers fed on a diet low non-phytate phosphorus. Brit Poult Sci. 2005;46:464–469. doi: 10.1080/00071660500191098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines M., Knopov V., Bar A. Involvement of osteopontin in egg shell formation in the laying chicken. Matrix Biol. 1996;14:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(05)80019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzolante C.C., Saldanha E.S.P.B., Lagana C., Kakimoto S.K., Togashi C.K. Effects of calcium levels and limestone particle size on the egg quality of semi-heavy layers in their second production cycle. Braz J Anim Sci. 2009;11:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sodek J., Ganss B., McKee M.D. Osteopontin. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11(3):279–303. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischler A., Halas V., Tossenberger J. Effect of dietary NPP level and phytase supplementation on the laying performance over one year period. Poljoprivreda. 2015;21(1):68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Um S.J., Paik K.I. Effect of microbial phytase supplementation on egg production, eggshell quality and mineral retention of laying hens fed different level of phosphorus. Poult Sci. 1999;78:75–79. doi: 10.1093/ps/78.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J.H., Han J.C., Wu S.Y., Xu M., Zhong L.L., Liu Y.R. Supplemental wheat bran and microbial phytase could replace inorganic phosphorus in laying hens diets. Czech J Anim Sci. 2007;52(11):407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ziaei N., Shivazad M., Mirhadi S.A., Gerami A. Effects of reduced calcium and phosphorous diets supplemented with phytase on laying performance of hens. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12(10):792–797. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.792.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyla K., Mika M., Swiatkiewicz S., Koreleski, Piironen J. Effects of phytase B on laying performance, eggshell quality and on phosphorus and calcium balance in laying hens fed phosphorus-deficient maize–soybean meal diets. Czech J Anim Sci. 2011;56(9):406–413. [Google Scholar]