Abstract

The objective of the review was to assess the potential of indigenous browse trees as sustainable feed supplement in the form of silage for captive wild ungulates. Several attempts to use silage as feed in zoos in temperate regions have been conducted with success. Information on silage from the indigenous browse trees preferred by wild ungulates in southern Africa is scanty. The use of silage from the browse trees is of interest as it has potential to reduce or replace expensive feed sources (pellets, fruits and farm produce) currently offered in southern African zoos, game farms and reserves, especially during the cold-dry season. Considerable leaf biomass from the indigenous browse trees can be produced for silage making. High nutrient content and minerals from indigenous browsable trees are highly recognised. Indigenous browse trees have low water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) that render them undesirable for fermentation. Techniques such as wilting browse leaves, mixing cereal crops with browse leaves, and use of additives such as urea and enzymes have been studied extensively to increase WSC of silage from the indigenous browse trees. Anti-nutritional factors from the indigenous browse preferred by the wild ungulates have also been studied extensively. Indigenous browse silages are a potential feed resource for the captive wild ungulates. If the browse trees are used to make silage, they are likely to improve performance of wild ungulates in captivity, especially during the cold-dry season when browse is scarce. Research is needed to assess the feasibility of sustainable production and the effective use of silage from indigenous browse trees in southern Africa. Improving intake and nutrient utilisation and reducing the concentrations of anti-nutritional compounds in silage from the indigenous browse trees of southern Africa should be the focus for animal nutrition research that need further investigation.

Keywords: Anti-nutritional factors, Indigenous browsable trees, Nutritive value, Silage, Ungulates

1. Introduction

Ungulate species inhabit most parts of southern Africa and their survival depends on plants, which provide adequate nutrients. In natural environments, they survive by using their feeding skills and walking long distances to select feed that meet nutritional requirements for growth, maintenance and reproduction (Boone et al., 2006). In captivity, the availability of feed that is in commensuration with the natural environment is limited; therefore, for alternative dietary items they rely on feed supplied with adequate nutrients. Animals in captivity are fed various dietary items such pellets, grass hay (grass species depends on the area), lucerne hay (Medicago sativa), browse (seasonally available) and fresh produce that depends on market availability. The chosen dietary items should meet the animal's protein and energy requirements with minimum exposure to dangerous toxins (Mbatha et al., 2012). Furthermore, they must be appealing and palatable to animals.

The worst-affected ungulate species in captivity are browsers and mixed-feeders. Some examples of browsers in southern Africa are giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis), black rhinos (Diceros bicornis), kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) and bushbuck (Tragelaphus sylvaticus). Mixed-feeders include springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), elephants (Loxodonta africana) and impalas (Aepyceros melampus). Diets of browsers constitute mostly of shoots, shrubs, tender twigs, fruits and pods from trees (Aganga and Mesho, 2008, Jamala et al., 2013). During rainy seasons mixed-feeders tend to feed on high-quality grasses of different heights while switching to browse as grass nutrient quality declines, especially during the dry season (Botha and Stock, 2005). It has been reported that most trees shed their leaves and loose most of their nutrients during this period. Thus, in captivity it is not a challenge to provide sufficient browse in wet season and the diet of browsers is optimally balanced. The harvesting logistics, therefore, represent one of the most crucial aspects of feeding browse to animals during dry season (Nijboer et al., 2003, Hatt and Clauss, 2006, Wensvoort, 2008). Browse is an important dietary item of browsers, thus, insufficient nutrients due to deficient browse supply may result in diseases, abnormalities, under-performance and eventually death (Clauss et al., 2008, Mbatha et al., 2012). Some browse species are relatively nutritious and can provide substantial amounts of nutrients, including fibre and protein. They can also stimulate natural behaviours and thus have high enrichment value for captive wild ungulates. One significant challenge with the use of browse is that the secondary metabolites (condensed tannins, alkaloids, terpenes) might be presented at dangerously high levels causing deleterious effects to captive wild ungulates. There are, however, beneficial effects to some captive wild ungulates when secondary metabolites are consumed. Tannins, for example, have a potential to mitigate iron overload disorder in wild ungulates (Lavin, 2012).

There are various methods of conserving browse such as freezing and drying. These methods require more storage space, are costly and labour intensive. Currently, browse silage is the best conserving technique because it is affordable and easy to make. The research on browse silage using southern African browse species is scarce. The information can benefit zoological institutions, protected areas and/or nature reserves, feed compounders and game farms. The willow (Salix alba) and poplar (Populus Canadensis) browse was ensiled by the Rotterdam Zoo (Hatt and Clauss, 2001). The Zurich zoo ensiled willow, hazel and maple tree species foliage (Hatt and Clauss, 2001). Wensvoort (2008) used sidr (Zizyphus spina-cristi), damas (Conocarpus lancifolius), saltbush (Atriplex spp), ghaf (Prosopis cinerea), ghaf al bahr (Pithecellobium dulce), leucaena (Leucaena leucocephalia), rakh (Salvadoria persica) and date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) for browse ensilage in the United Arab Emirates. According to Lachance (2012), the Toronto Zoo used trees from apple orchards to prepare browse silage.

The main objective of ensiling is to preserve browse with minimum loss of nutrients. Silage is the conservation of forage with high moisture by natural fermentation under anaerobic conditions, where beneficial organisms such as bacteria, yeasts and fungi convert plant energy sources to organic acid (Hurst, 1971). During preservation, the fodder will undergo acid fermentation when bacteria produce lactic, acetic and butyric acids from sugars present in plant material. The main principle is the establishment of low pH and the maintenance of anaerobic conditions. When sufficient acid is produced to lower the pH to approximately 4.0, most metabolic actions cease and the forage is preserved. Under ideal situations, microbes will quickly thrive, multiply and dominate the silage mass. Maintaining the nutritional value (energy, DM and crop quality) of silage during the storage period is essential to successful ensiling programmes (Muck et al., 2003).

The objective of this review was to assess alternative feed sources to feed captive wild ungulates in southern Africa. The review focuses on nutritional value of the browse tree species, their availability and possibilities of conserving the browse trees by ensiling. It also highlights the recommendations to enhance the sustainable production and utilisation of the silage from the browse trees to benefit captive wild ungulates.

2. Browse species of southern Africa

Indigenous browse species that are dominant in most parts of southern Africa have an important role to provide feed for wild ungulates. They can be classified into deciduous, semi-deciduous and evergreen plants.

Deciduous plants, including trees, shrubs and herbaceous perennials, are those that lose all of their leaves, especially during cold-dry conditions (winter) in southern Africa. A number of deciduous plants channel nitrogen and carbon from the foliage and store them in vacuoles of parenchyma cells in their roots and inner bark before they are shed. In spring the nitrogen is used for growth of new leaves or flowers (Srivastava, 2002). Some examples of deciduous browse in southern Africa are: Acacia spp., Bolusanthus speciosus, Combretum spp., Terminalia, Erythrina lysistemon, Robinia pseudoacacia, Commiphora spp., Grewia occidentalis, Ziziphus mucronata, Pappea capensis, Balanites maughamii, Brachystegia spp., Burkea africana and Dichrostachys cinerea (Van Wyk et al., 2000). Semi-deciduous trees and bushes are plants that normally loose part of their foliage during the dry season. They might lose all their leaves especially during severe dry conditions (drought) (Scogings et al., 2004). Some examples of semi-deciduous browse in southern Africa are Schotia brachypetala, Heteropyxis natalensis/dehniae, Brachylaena discolour, Antidesma venosum, Ficus polita, Boscia albitrunca and Colophospermum mophane (Van Wyk et al., 2000). Evergreen browse keep their leaves throughout the year. Some of the evergreen browses in southern Africa are Carissa bispinosa, Euclea divinorum, Gymnosporia senegalensis, Boscia foetida and Diospyros spp. (Van Wyk et al., 2000).

The use of indigenous browse trees as feed for wild ungulates is associated with features such as abundance and accessibility, quality in terms of available protein, energy, minerals and vitamins, and presence of anti-nutritional factors (Kibria et al., 1994, Ramírez, 1998). Few indigenous browse species have been investigated and evaluated for their foliage biomass production and their chemical and physical characteristics. The information is important to ensure suitability and a ready supply of browse for ensiling.

2.1. Biomass production from browse species in southern Africa

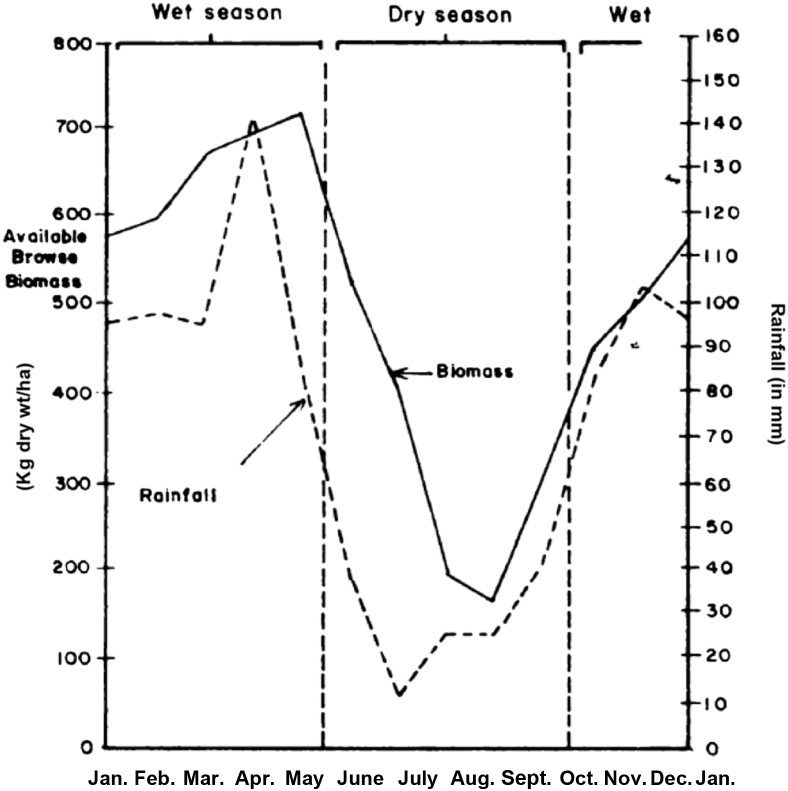

Consumable biomass from browse is influenced by biotic, abiotic and anthropogenic factors. Regarding climatic (abiotic) factors, more consumable biomass is produced during the wet seasons. As rainfall decreases into the dry season, plant biomass and quality gradually decrease as well. This is due to leaf dormancy, lignification of existing shoots and falling of leaves (Pellew, 1980). Consumable biomass reached production peak of 712 kg/ha during the wet season and a minimum of 167 kg/ha during the dry season on the ridge-top acacia regeneration woodland in the Serengeti National Park (Fig. 1). Browse can, therefore, be harvested during the wet season when in abundance and conserved as silage to be used as feed during the dry season.

Fig. 1.

Effects of rainfall patterns on consumable biomass production per hectare for sample area of ridge-top acacia regeneration woodland. Source: Pellew (1980).

Polis (1999) described how the availability of soil nutrients can have an impact on plant productivity and aboveground biomass. The use of resources from soil by trees largely depends on rainfall patterns, which have effects on nutrient uptake and storage (Parks et al., 2000, Shane et al., 2004). Rainfall dissolves nutrients in the soil; hence, roots can absorb it. On the other hand, if nutrients are not dissolved there will be no uptake of nutrients from the soil. Consequently, plant growth is hindered (Kambatuku et al., 2011). Fires can prevent tree establishment and growth by killing tree seedlings or seriously damaging the aboveground parts of shrubs and trees (Sinclair et al., 2009). Therefore, this may result in reduction of consumable biomass.

In the wild, ungulates use their foraging skills to access consumable biomass. One of the skills is the bipedal stance where an animal stands on its hind legs to access biomass at considerable height (Fig. 2). Other ungulates like giraffes have adapted by developing a long neck to access consumable tree biomass not reachable by other ungulate species. In captivity, human beings harvest the consumable browse biomass for the ungulates. Different tools can be used to harvest browse, including secateurs, pruning clippers, cutlasses, loppers and sickles, depending on the height of the tree. The browse is harvested in such a way that trees are not permanently damaged allowing them to recover. The harvested browse can be conserved in the form of silage and can be used to prepare pellets, such as Boskos (Section 4.1.2).

Fig. 2.

Bipedal stance by antelope to reach consumable biomass.

2.2. Chemical composition of browse species of southern Africa

2.2.1. Nutritional characteristics of browse species

Indigenous trees are important source of nutrients for both domesticated and wild ungulates in southern Africa. Browse is rich in protein and their chemical composition tends to vary little across seasons compared with grasses (Lukhele and Van Ryssen, 2003). The deep root system of trees allows them to extract nutrients from deep soil layers, which are inaccessible to shallow rooted plants such as grasses and herbaceous plants. This makes them a good source of nutrients for wild ungulates (Ngwa et al., 2004).

Variations in chemical compositions have been noted among different vegetation types of southern Africa. In karoo vegetation (Louw et al., 1968), crude protein content varied from around 5% to 20%, and is generally about 3% higher (in the same species) in summer than it is in winter. According to Aucamp (1979), in the second form of karroid vegetation, the valley bushveld showed crude protein levels to range from a minimum of 10.5% in September–November (early wet season) to 14.5% in February–May (late wet to early dry season). This might change due to effects of climate change on vegetation. Apart from season and edaphic factors that affect chemical composition of these trees, stage of maturity, plant parts and genetic predisposition are important (Underwood and Suttle, 1999, Bechaz, 2000, Grant et al., 2000, Dambe et al., 2015). Regarding stage of maturity of the plant, new shoots are highly nutritious compared with mature leaves. New shoots had high crude protein and magnesium, whilst mature leaves had high DM and fibre content (Balehegn and Hintsa, 2015). Fibre content increases due to accumulation of lignin. Consumable plant parts have been observed to have different chemical compositions (Table 1). Wild ungulates obtain more nutritional benefits from consuming leaves than barks and stems.

Table 1.

Average values of different chemical components of browse (dry matter basis).1

| Browse species | Plant part | DM | CP | EE | CF | NFE | NDF | Ash | NFC | Ca | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. thonningii | Bark | 21.41 | 3.31 | 6.3 | 24.67 | 65.72 | 47.52 | 20.36 | 22.51 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

| Leaf | 35.21 | 14.37 | 3.76 | 16.59 | 70.28 | 35.12 | 19.12 | 32.63 | 0.21 | 0.46 | |

| Twig | 47.69 | 6.39 | 4.05 | 23.17 | 66.39 | 39.59 | 19.07 | 30.89 | 0.34 | 0.38 | |

| A. tortilis | Pods | – | 17.3 | 3.1 | 24.8 | 49.1 | – | 5.7 | – | 0.79 | – |

| Leaf | – | 19.2 | 6.1 | 11.6 | 54.4 | – | 8.7 | – | 2.27 | – | |

| A. mellifera | Fresh leaves | 99.0 | 14.5 | – | 36.1 | – | – | – | – | 2.26 | 0.23 |

| Bark | 99.1 | 11.2 | – | 39.3 | – | – | – | – | 2.15 | 0.13 | |

| C. mopane | Fresh leaves | 98.2 | 13.4 | – | 22.4 | – | – | – | – | 1.15 | 0.12 |

| Bark | 98.2 | 4.62 | – | 30.1 | – | – | – | – | 1.24 | 0.11 | |

| G. bicolor | Fresh leaves | 98.9 | 13.1 | – | 22.2 | – | – | – | – | 1.27 | 0.21 |

| Bark | 98.3 | 6.12 | – | 38.6 | – | – | – | – | 2.38 | 0.09 |

DM = dry matter, CP = crude protein, EE = ether extract, CF = crude fibre, NFE = nitrogen free extracts, NDF = neutral detergent fibre, NFC = non fibrous carbohydrate.

Sources: Balehegn and Hintsa, 2015, Ghol, 1981, and Dambe et al. (2015).

2.2.2. Secondary plant metabolites in browse trees

Most browse trees in southern Africa have been observed to have different types of anti-nutritional factors/secondary plant metabolites (SPM). These are chemicals produced by plants that are not used for primary plant metabolism. They function as feeding deterrents and have evolved to protect plants from herbivory that can quickly defoliate them. Some of the different SPM found in various browse species in southern Africa are shown in Table 2. Under natural conditions there is little danger that wild ungulates will be poisoned because they will seldom consume large quantities of pods or leaves with SPM. Ungulates use the dilution approach, which involves feeding on SPM-rich plants and later diluting by feeding on plants with fewer SPM (Bhat et al., 2013). Rogosic et al. (2007) described adaptation of microbes in the gut of an animal to tannins. Microbes degrade the SPM, enabling animals to more efficiently use tannin-rich plants. Another way animals detect and avoid intoxication from the SPM is through post-ingestive feedback from nutrients and toxins (Burritt and Provenza, 1996). They learn about post-ingestive consequences of forage through affective and cognitive systems. Austin et al., 1989, Robbins et al., 1995 also described browsers to have large parotid salivary glands, which produce tannin-binding proteins that may prevent tannins in browse to reduce protein digestibility. Thus, the protein affinity of SPM is reduced early in the gastro-intestinal tract. Consumption of tannin rich browse, even when ensiled, is unlikely to have adverse effects on captive wild ungulates.

Table 2.

Plant secondary metabolites in different browse species in southern Africa.

| Anti-nutritional factor | Browse species | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Glycosides | A. cunninghamii, A. sieberiana, Barteria fistulosa, Bambusa bambos, Albizia stipulate, Bassia latifolia, Sesbania sesban, Diospyros lycioides | Coates, 2002, Palgrave et al., 2002 |

| Alkaloids | Acacia berlandier, Acacia adunca, Sesbania vesicaria, S. drummondii, S. punicea, Erythrina spp. | White, 1951, Palmer and Pitman, 1972, Palgrave, 1977 |

| Triterpenes | Azadirachta indica, Commiphora glandulosa, Euphorbia bothae, Combretum collinum | Popplewell et al., 2010, Songca et al., 2013 |

| Oxalates | Acacia spp. | |

| Polyphenolic compounds; Condensed tannins | Acacia species, Dichrostachys species, Schotia brachypetala, Burkea africana, Buddleja salviifolia, Celtis africana, Rhus/Searsia lancea, Diospyros mespiliformis, Ficus sycomorus, Combretum hereroense and Terminalia serecea, Bauhinia galpinii, Ozoroa paniculosa, Sclerocarya birrea, Euclea species | Owen-Smith (1993) |

2.3. Physical features of browse species of southern Africa

Apart from SPM, indigenous browse species also defend themselves from herbivory by developing physical features as a first line of defence. These physical features include thorns, spines, prickles and trichomes. Some browse species that use thorns as herbivory deterrent in southern Africa are Acacia spp., Dichrostachys cinerea, Faidherbia albida, Ziziphus mucronata, Gymnosporia maranguensis, Scutia myrtina, and C. bispinosa. Despite the complex defensive mechanisms of the browse species, they are still prone to herbivory. This is mainly because ungulates have some mouth features that enable them to feed on browse trees. Giraffes, for example, have long, tough tongues that enable them to draw foliage towards the front lower teeth, which function as combs for stripping branches against the toothless upper palate without being hurt by the thorns during feeding (Milewski et al., 1991). Hofmann (1973) described giraffes as being able to ingest fully matured, hard thorns with apparent indifference. Other phenotypic mouth features of the browsers which allow them to fully utilise browse plant species are a narrow mouth and highly mobile lips (Clauss et al., 2008). The features increase harvesting efficiency of leaves whilst avoiding deterrent features on plants such as thorns. Therefore, browse will always be available as feed for ungulates in the wild. Depending on mouth features and skills that each browser has developed, the preference of browse species will differ.

3. Browse species preferences of wild ungulates in southern Africa

Browse species preferred by the selected ungulates in southern Africa are given in Table 3. Preference of browse is influenced by the constantly changing environment and human intervention. Environmental change usually has to do with seasons and climate change. Ungulates change their feeding habits and plant preferences with season. Changing of feeding habits is mostly observed in intermediate feeders such as springboks (A. marsupialis), elephants (L. africana) and impalas (A. melampus). When grass quality is poor and scarce during the dry season, they switch to feeding on browse leaves.

Table 3.

Browse plant species preferred by different types of ungulates in southern Africa.

| Animal spp. | Plant spp. |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Browse spp. | Grass species | ||

| Browsers | |||

| Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) | Acacia spp., Commiphora spp., Rhus spp., Combretum imberbe, Ehretia rigida, Pappea capensis, Peltophorum africanum | – | Blomqvist and Renberg (2007) |

| Black rhinos (Diceros bicornis) | Longispina, Combretum spp., Terminalia spp., Euphorbia bothae | – | Kingdon, 1997, Parker and Bernard, 2005, |

| Kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) | Colophospermum mopane, Grewia bicolor, Terminalia,prunioides, Tinnea rhodesiana, Boscia albitrunca, Combretum apiculatum, Combretum mopane | – | Hooimeijer et al. (2005) |

| Mixed feeders | |||

| Springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) | Acacia erioloba, Grewia flava, Rhigozum trichotomum | Themeda triandra, Schmidtia kalahariensis, Stipagrostis obtusa | Stapelberg et al. (2008) |

| Elephant (Loxodonta africana) | Acacia burkei, Afzelia quanzensis, Albizia adianthifolia, Dialium schlechteri, Manilkara discolor, Sapium integerrimum, Spirostachys africanum | Panicum maximum, Cynodon dactylon, Themeda cymbaria, Themeda triandra, Phleum pratense | Klingelhoefer (1987), De Boer et al. (2000) |

| Impala (Aepyceros melampus) | Acacias, D. Cinerea, Leucas capensis, Asparagus striatus, Sansevieria hyacinthoides, Grewia robusta, Diospyros dicrophylla, Euclea undulata, Jatropha capensis | P. maximum, U. mosambicensis, Eragrostis obtusa, Asparagus striatus, Sporobolus fimbriatus, Themeda triandra | Stapelberg et al. (2008), Koekemoer (2001) |

Through management practices, humans play an important role in influencing plant preferences of ungulates as they decide on where to relocate ungulates to prevent conflicts with humans. Furthermore, poor management practices like overstocking will cause extinction of palatable plant species through overgrazing and/or over-browsing. Animals will have no other alternative but to select the remaining unpalatable plant species within a piece of land to get nutrients that meet their requirements for growth, maintenance and reproduction.

Knowing plant species preferences can be the first step towards gaining an understanding of the ideal and acceptable browse species for the ungulates. This knowledge may be used when formulating diets and choosing the right palatable plant species for ensiling that meet nutrient requirements for growth, maintenance and reproduction of captive wild ungulates.

4. Feeding management for captive wild ungulates in southern Africa

4.1. Feed offered to captive wild ungulates

Information accrued from preference studies may guide zoo nutritionists to identify dietary items for captive ungulates. Most browse species preferred by wild ungulates are scarce during the cold and dry season. Hence, zoo nutritionists resort to adding other dietary items such as grass hay, legume hay, pellets and fresh produce to diets of captive ungulates (Gattiker et al., 2014).

4.1.1. Hay

Hay of various types generally constitutes the mainstay of feeding programmes for domesticated and captive animals. In southern Africa, it is usually prepared by using Cynodon dactylon, Eragrostis tef, Eragrostis curvula, Chloris gayana, Digitaria eriantha and Cenchrus ciliaris (Tainton, 2000, Mbatha et al., 2012). The chemical composition of hay can vary widely depending largely on soil fertility, plant species and stage of maturity when they are harvested. High proportion of legume hay is offered to browsers whereas grass hay is sufficient for most grazers or bulk feeders such as zebras, elephants and buffaloes. Despite efforts to feed high-quality hay to captive ungulates, problems have been reported that animals tend not to accept it as feed. High refusal rates of grass hay have been reported in giraffes (Gutzwiller, 1984) and duikers (Van Soest et al, 1995). Feeding on hay alone will also not provide optimal nutrients to the captive ungulates for growth, maintenance and reproduction. A combination of hay and other feedstuffs such as pellets and fresh produce are mostly fed to the captive ungulates.

4.1.2. Pellets

Pellets contain a variety of ingredients ranging from abundant protein and energy sources to vitamins and minerals in one form. The pellets are formulated in such a way that captive ungulates have a nutritionally complete diet (Crissey et al., 2001). Furthermore, they are formulated to specifically meet physiological requirement of certain animal species. Browsers are normally fed pellets containing legumes such as leaves from Acacia spp. In southern Africa, Boskos game pellets are a widely recognised feed for game animals. They are produced from natural bushveld acacia and pelletized to avoid selective eating, minimise wastage, and provide ease of handling and extended shelf life (Clauss et al., 2006). Acacias are rich in natural trace elements. Nutrients and fibres from Boskos pellets are immediately available in herbivores' metabolism, which assist with easier digestion. There are, however, drawbacks in the use of pellets for ungulates in captivity such as high production costs. Therefore, zoological gardens find it difficult to source money to feed pellets to the ungulates. In addition, several studies have reported some metabolic disorders associated with feeding pellets to captive ungulates (Hummel et al., 2006, Clauss et al., 2009, Zenker et al., 2009). One of these metabolic disorders is acidosis. High levels of rapidly digestible carbohydrates in pellets decrease rumen pH (Cheeke and Dierenfeld, 2010); as such, the gut becomes atonic resulting in depressed appetite. Worst scenarios result in shock and even death. Rumen acidosis has also been linked to the development of other health problems such as laminitis (Zenker et al., 2009) and diarrhoea (Hummel and Clauss, 2006).

4.1.3. Fruits and vegetables

Fruits and vegetables are commonly fed to ungulates in captivity (Huisman et al., 2008). They are rich in fructans and are readily fermented feedstuffs. Their consumption is associated with a wide range of health problems such as rumen acidosis, laminitis and other hoof problems, as well as glycosuria when these they are used in large quantities (Clauss and Kiefer, 2003, Vercammen et al., 2006, Zenker et al., 2009). With regard to laminitis, Gram-positive bacteria in the caecum break down fructans resulting in the development of lactic acidosis and endotoxemia (Van Eps and Pollitt, 2006). Lactic acidosis and endotoxemia activates local metalloproteinases that break down the basement membrane, causing a detachment of the distal phalanx from the inner hoof wall. The fructans are an important contributing factor to the likelihood of the conditions developing in giraffes (Hummel et al., 2006); as such, recommendations have been put forward to limit the amount of fruits and vegetables to be offered to captive wild ungulates.

4.2. Necropsy reports from captive ungulates fed hay, pellets and fructans

Captive ungulates, in general, are more susceptible to gastrointestinal diseases (Hatt and Clauss, 2006). The majority of these gastrointestinal disorders are not infectious but are presumably due to problematic feeding. A study by Gattiker et al. (2014) reported more than 25 cases of metabolic disorders in necropsy of captive ungulate species fed hay, pellets and fructans in zoological gardens of South Africa (Table 4). Browsers, particularly the greater kudu (T. strepsiceros) and giant eland (Taurotragus derbianus) had the worst body condition scores compared with intermediate feeders and grazers at necropsy. Browsers such as giraffes were more prone to ruminal acidosis, rumenitis and parakeratosis at time of death.

Table 4.

Metabolic disorders in necropsy reports of 30 captive ungulate species fed hays, pellets and fructans in zoological gardens of South Africa.1

| Species | Common name | FT2 | n | PRA3, % | Body condition4 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P, % | R, % | G, % | Ex, % | |||||

| Alcelaphus buselaphus | Hartebeest | GR | 6 | 0 | 33.3 | 0 | 16.6 | 16.7 |

| Antilope cervicapra | Blackbuck | GR | 35 | 5.7 | 37.1 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| Addax nasomaculatus | Addax | GR | 16 | 12.5 | 18.8 | 6.2 | 18.7 | 18.8 |

| Damaliscus pygarus | Bontebok | GR | 6 | 16.7 | 66.7 | 16.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Hipportragus niger | Sable antelope | GR | 8 | 12.5 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kobus leche | Lechwe | GR | 23 | 17.4 | 30.4 | 4.4 | 8.7 | 17.4 |

| Oryx dammah | Scimitar-horned oryx | GR | 16 | 6.3 | 43.8 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.3 |

| Oryx leucoryx | Arabian oryx | GR | 19 | 15.8 | 36.8 | 10.6 | 5.3 | 15.8 |

| Syncerus caffer | African buffalo | GR | 14 | 21.4 | 35.7 | 0 | 0 | 7.1 |

| Ammotragus lervia | Barbary sheep | IM | 31 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Antidorcas marsupialis | Springbok | IM | 52 | 42.3 | 44.2 | 9.6 | 11.6 | 1.9 |

| Aepyceros melampus | Impala | IM | 42 | 7.1 | 14.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 7.1 |

| Axis axis | Chital | IM | 30 | 6.7 | 10 | 10 | 13.3 | 10 |

| Axis porcinus | Hog deer | IM | 23 | 8.7 | 13 | 13.1 | 4.3 | 17.4 |

| Boselaphus tragocamelus | Nilgai | IM | 10 | 10 | 50 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

| Capra nubiana | Nubian ibex | IM | 59 | 13.6 | 35.6 | 1.7 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

| Hemitragus jemlahicus | Tahr | IM | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nanger dama | Dama gazelle | IM | 23 | 34.8 | 34.8 | 13 | 13 | 0 |

| Ovis aries | Sheep | IM | 9 | 0 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ovis nivicola | Snow sheep | IM | 18 | 0 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.1 |

| Raphicerus campestris | Steenbok | IM | 30 | 3.3 | 33.3 | 3.4 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Tragelaphus angasii | Nyala | IM | 37 | 13.5 | 40.5 | 8.1 | 2.7 | 0 |

| Taurotragus derbianus | Giant eland | BR | 10 | 20 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Taurotragus oryx | Common eland | IM | 4 | 0 | 50 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalophus natalensis | Red forest duiker | BR | 19 | 15.8 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Giraffa camelopardalis | Giraffe | BR | 8 | 50 | 62.5 | 0 | 12.5 | 0 |

| Philatomba monticola | Blue duiker | BR | 37 | 13.5 | 51.4 | 8.1 | 2.7 | 0 |

| Sylvicapra grimmia | Common duiker | BR | 34 | 8.8 | 38.2 | 0 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Tragelaphus imberbis | Lesser kudu | BR | 5 | 0 | 60 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Tragelaphus strepsiceros | Greater kudu | BR | 14 | 28.6 | 78.6 | 7.1 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Gattiker et al. (2014).

Feeding type (FT) is abbreviated as grazer (GR), intermediate feeder (IM), or browser (BR).

Prakeratosis/ruminitis/acidosis (PRA) includes ruminal acidosis, rumenitis, and parakeratosis.

Body condition is denoted as poor (P), reasonable (R), good (G), or excellent (Ex).

Most feeds like hay, pellets and fruits when offered daily, predispose the captive animals to hemosiderosis or haemochromatosis, usually referred to as iron storage disease. Hemosiderosis is a form of iron overload disorder, which results in the accumulation of hemosiderin. In the wild, ungulates are not susceptible to this condition because of phenolic compounds (tannins) in their diets. High amounts of iron in consumed feedstuffs are reduced because of the binding properties of the phenolic compounds. On the contrary, alternative feeds offered to captive ungulates are high in iron (Castell, 2005) and low in iron chelates, such as tannins (Wright, 1998). Low iron chelates result in excessive storage of iron in the liver of the animal. Previous studies involving black rhinoceros have shown the amount of iron to increase with time when kept in captivity (Smith et al., 1995, Paglia and Dennis, 1999, Dierenfeld et al., 2005). The diet of black rhinoceros in the wild mostly consists of twigs, leaves bark and shrubs, which contain high levels of natural antioxidants and chelators, which reduce bioavailability of dietary iron (Clauss et al., 2002). Treatments of the condition are only successful when iron levels in the system are still low.

Notwithstanding all the efforts to provide alternative feed for captive wild ungulates during the period when browse is unavailable, there is also a need to supply food that is in commensuration with the natural environment. The use of silage from indigenous browse species of southern Africa as feed for the captive wild ungulates is one of such alternative.

5. Ensiling browse tree species

Ensiling of forages is a method of conservation in many parts of the world for livestock production. It makes feed available all year round even during seasons when browse is scarce (Wilkinson and Davies, 2012). Plants species like grasses, whole-crop cereals and legumes are suitable for ensiling. Compared with hay, ensiling does not affect nutrient composition (Teixeira et al., 2003, Wanjekeche et al., 2003). Browse silage is used mostly for captive animals while it can be profitable for livestock production of mixed-feeders such as goats. Furthermore, when well-prepared it is more palatable than hay.

The process of making browse silage involves the pruning of leaves, stems and fruits from selected browse species. These can be chopped into smaller pieces (approximately 2 to 4 cm) put in plastic drums, polythene bags and/or even dug into the ground. The material is compressed to remove excess air to prevent spoilage. Silage must be firmly packed to minimize the oxygen content, or it will be spoilt. Oxygen supply and water-soluble carbohydrates become depleted, paving way for anaerobic fermentation to occur. High temperature reduces lactic acid concentrations resulting in increased pH levels and reduced dry matter (Koc et al., 2009). The ensiled browse will undergo acid fermentation when anaerobic bacteria (lactic acid bacteria – Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Lactococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus and Leuconostoc) produce lactic, acetic and butyric acids from sugars present in plants. The proportion of acids produced will depend on plant maturity, moisture and natural bacterial populations. When sufficient acid is produced to reduce the final pH to approximately 4.2, most metabolic actions cease and the forage is preserved. The type of forage and moisture content of ensiled crop usually influences final pH.

Legumes generally have less water-soluble carbohydrates, high buffering capacity and can reach a final pH of about 4.5. Corn silage, on the other hand, has high water-soluble carbohydrates, low buffering capacity and can reach a final pH of around 4.0. The smell of lactic acid (sour milk) when opening silage containers is the sign of good quality. On contrary, butyric acid (rancid fat) is an indication of silage poor quality. An extremely low fermentable and poor quality silage will have ammonia smell. Preservation of browse by ensiling is important, especially for dry periods when browse is scarce. The ensiled browse species can be used as an acceptable feed commensurate with the natural environment for the captive wild ungulates. Feeding silage is also not associated with metabolic disorders compared with feeding of pellets and fructans to captive wild ungulates.

5.1. Ensiling suitability of indigenous browse species of southern Africa

Most indigenous browse species of southern Africa are not the best ensilage material compared with temperate forages (Tainton, 2000). This is largely because they have low water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) that are essential for successful ensilage (Mcdonald, 1981, Tjandraatmadja et al., 1993, Nussio, 2005). Low WSC during ensiling leads to a higher buffering capacity and leaves protein susceptible to proteolysis (Woolford, 1984). Proteolysis may reduce the efficiency of nitrogen utilisation by the ungulates. There are, however, several practices that aim to improve the levels of fermentable carbohydrates, reducing buffering and preventing proteolysis so that good-quality silage can be produced. These include wilting, mixing legumes with cereal crops, silage additives and using small-scale silos. Wilting has been found to greatly increase DM and reduce proteolysis and anti-nutritional factors before the ensiling processes (Hashemzadeh-Cigari et al., 2011). Cereal crops have high WSC; hence, mixing the browse with cereal crops may produce a conducive environment for fermentation (Phiri et al., 2007).

Table 5 shows fermentation and nutritional quality of silage from leguminous trees, and mixture of crop and leguminous trees. Silages from leguminous browse trees are not suitable materials for fermentation unless a cereal crop is added. Browse species, especially in the tropics, will also need additives since they do not ferment quite readily (Tainton, 2000). Urea, ammonia and molasses might be used as additives. Wilting, mixing legumes with cereal crops, silage additives and using small-scale silos have been investigated in several studies to successfully produce silage for livestock in southern Africa (Bolsen, 1999, Titterton and Bareeba, 2000, Mugweni, 2000, Dewhurst et al., 2003, Phiri et al., 2007). There is paucity of information regarding making silage from other browse species preferred by wild ungulates. This, therefore, warrants further investigations.

Table 5.

Fermentation and nutritional quality of silages from maize and legume forages (Acacia boliviana, Calliandra calothyrsus, Gliricidia sepium and Leucaena leucocephala).1

| Silage type | Fermentation quality2 |

Nutritional quality |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | NH3:N, % | CP, % | OMD, % | |

| Maize and legume tree mixture | 4.0 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 56.0 |

| Maize + A. boliviana | 4.7 | 12.0 | 18.7 | 44.8 |

| Maize + C. calothyrsus | 4.1 | 11.6 | 14.0 | 37.5 |

| Maize + G. sepium | 4.2 | 8.5 | 15.5 | 59.1 |

| Maize + L. leucocephala | 4.6 | 12.8 | 17.2 | 49.3 |

| Legume tree | ||||

| A. boliviana | 6.3 | 11.0 | >24.0 | 40.9 |

| C. calothyrsus | 5.2 | 12.4 | 22.9 | 30.2 |

| G. sepium | 5.1 | 9.3 | 25.5 | 64.5 |

| L. leucocephala | 6.5 | 11.7 | 27.2 | 33.4 |

CP = crude protein; OMD = organic matter digestibility.

Source: Mugweni (2000).

Acidity of < pH5 needed for good preservation; NH3:N = Protein-N loss as ammonia (<15% is reasonable in legumes).

5.2. Effects of ensiling on detoxification of anti-nutritional factors

Previous studies have noted ensiling to be a means of reducing secondary plant metabolites (Ngwa et al., 2004, Martens et al., 2014, Huisden et al., 2014). Ngwa et al. (2004) found ensiling to reduce the content of cyanogenic glycosides (CG) in pods of Acacia sieberiana. The concentrations of cyanide in silage samples indicated that ensiling effectively reduced the cyanide content in the feed. The concentrations were brought down to nontoxic levels, although they did not completely eliminate the cyanide in the pods. It was suggested that this may relate to the fact that cyanide in most plants exists in 2 forms: CG, which is metabolised by microorganisms during the process of fermentation, and non-glycosidic cyanide, which is not metabolised (Izomkun-Etiobhio and Ugochukwu, 1984).

Free condensed tannins available to bind to proteins were also reduced by ensiling in some tropical forage legumes (Martens et al., 2014). Huisden et al. (2014) found ensiling to reduce L-3 and 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine concentration in Mucuna pruriens. The process of detoxification is likely to make it possible for the ungulate species to consume silage from a variety of indigenous browse species in large quantities without any deleterious side effects. Therefore, performance of captive wild ungulates can be improved.

5.3. Effects of feeding silage on performance of ungulates

It has been noted that silage from crops, grasses, legume trees and ley legumes is readily digested by domesticated ungulates (cattle, sheep and goats) and has led to improvements in their performance (Mapiye et al., 2007, Salcedo et al., 2010, Helander et al., 2014). Feeding grass silage increased daily live weight and carcass gains in sheep and beef cattle (Helander et al., 2014). In dairy cattle, feeding with red clover silage and corn silage increased milk yield, protein concentration and the yields of fat plus protein (Salcedo et al., 2010).

Wild ungulates, like their domesticated counterparts, the ruminants (cattle, sheep and goats), can digest fibrous diets (Hofmann, 1989, Clauss et al., 2008). In a study conducted by Nilsson et al. (1996), silage made from grass was found to be highly acceptable by the ungulates. Intake of grass silage increased over time when introduced to reindeer (Fig. 3). Live weight gain was also found to increase in reindeer fed low dry matter silage (Nilsson et al., 1996). It is very likely that wild ungulates in southern Africa will also perform to expectation when offered the silages from the indigenous browse trees. Very few, if any, studies have been documented to determine in southern Africa on how the captive wild ungulates fed silage will perform in terms of growth and reproductive performance in southern Africa. This, therefore, warrants further investigation.

Fig. 3.

Daily silage intake (SI) and dry matter intake (DMI) of reindeer fed silage with high (- - -) or low (___) dry matter content. Vertical lines indicate the slaughter occasions. Adopted from Nilsson et al. (1996).

6. Concluding remarks, economic implications and future directions regarding the use of silage as feed for captive ungulates

There is a need for alternative feed sources for captive wild ungulates in zoos, game farms and game reserves in southern Africa due to insufficient supply and high prices of existing feed sources. The alternative feed source can be obtained from leaves of browse trees. These leaves can be conserved by ensiling. Hatt and Clauss (2001) highlighted the fact that feeding captive ungulates with silage from browse species can be more cost-effective than feeding hay, pellets and farm produce. The objective of this paper was to review the current knowledge in the literature regarding the use of browse silage as feed for captive wild ungulates. Information on feeding of browse silage to captive wild ungulates in southern Africa is scanty. As a result, much of the information in the review is giving references to studies in temperate regions and also livestock species in southern Africa. Using browse silage as a feed source for captive wild ungulates is generally safe and it does not run high risks of introducing hazardous substances that can be have deleterious effects on animal well-being. For sustainable production of silage, there is a need to understand foliage biomass, anti-nutritional factors and fermentation chemistry of different browse species preferred by wild ungulates in southern Africa. Future research should also aim at improving potential of browse silage as alternative feed source by observing responses in terms of growth and reproduction in captive wild ungulates in southern Africa.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Aganga A.A., Mesho E.O. Mineral contents of browse plants in Kweneng district in Botswana. Agric J. 2008;3(2):93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aucamp A.J. University of Pretoria; South Africa: 1979. Die produksiepotensiaal van die valleibosveld as weiding vir boer- en angorabokke. [DSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Austin P.J., Suchar L.A., Robbins C.T., Hagerman A.E. Tannin binding proteins in the saliva of deer and their absence in the saliva of sheep and cattle. J Chem Ecol. 1989;15:1335–1347. doi: 10.1007/BF01014834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balehegn M., Hintsa K. Effect of maturity on chemical composition of edible parts of Ficus thonningii Blume (Moraceae): an indigenous multipurpose fodder tree in Ethiopia. Livest Res Rural Dev. 2015;27:12. [Google Scholar]

- Bechaz F.M. South Africa University of Pretoria; 2000. The influence of growth stage on the nutritional value of Panicum maximum (cv. Gatton) and Digitaria eriantha spp. eriantha silage for sheep. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat T.K., Kannan A., Singh B., Sharma O.P. Value addition of feed and fodder by alleviating the antinutritional effects of tannins. Agric Res. 2013;2:89–206. [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist P.A., Renberg L. University of Uppsala; 2007. Feeding behaviour of giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) in Mokolodi reserve, Botswana. Minor Field Study. [Google Scholar]

- Bolsen K.K. Biotechnology in the feed industry, Proceedings of the 15th Annual Symposium. Nottingham University; UK: 1999. Silage management in North America in the 1990s. [Google Scholar]

- Boone R.B., Thirgood S.J., Hopcraft J.G.C. Serengeti wildebeest migratory patterns modelled from rainfall and new vegetation growth. Ecology. 2006;87:1987–1994. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1987:swmpmf]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha M., Stock W. Stable isotope composition of faeces as an indicator of seasonal diet selection in wild herbivores in southern Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2005;101:371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Burritt E.A., Provenza F.D. Amount of experience and prior illness affect the acquisition and persistence of conditioned food aversions in lambs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1996;48:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Castell J. University of Munich; Germany: 2005. Untersuchungen zu fü tterung und verdauungsphysiologie am spitzmaulnashorn (Diceros bicornis).Vet. [Med. Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeke P.R., Dierenfeld E.S. CABI; Oxfordshire: 2010. Comparative animal nutrition and metabolism. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M., Hummel J., Eloff P., Willats R. Sources of high iron content in manufactured pelleted feeds: a case report. In: Fidgett A., Clauss M., Eulenberger K., Hatt J.M., Hume I., Janssens G., Nijboer J., editors. Zoo animal nutrition Vol. III. Filander; Fürth: 2006. pp. 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M., Kaiser T., Hummel J. The morphophysiological adaptations of browsing and grazing mammals. In: Gordon I.J., Prins H.H.T., editors. The ecology of browsing and grazing. Springer; Heidelberg: 2008. pp. 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M., Keller A., Peemöller A. Postmortal radiographic diagnosis of laminitis in a captive European moose (Alces alces) Schweiz Arch Tierh. 2009;151:545–549. doi: 10.1024/0036-7281.151.11.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M., Kiefer B. Digestive acidosis in captive wild herbivores - implications for hoof health. Verhandlungsbericht Erkrankungen der Zootiere. 2003;41:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M., Lechner-Doll M., Hänichen T., Hatt J.M. Excessive iron storage in captive mammalian herbivores - a hypothesis for its evolutionary etiopathology. Proc Eur Assoc Zoo Wildl Vet. 2002;4:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Coates P.K. Struik Publishers; Cape Town: 2002. Trees of southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Crissey S., Dierenfeld E.S., Kanselaar J., Leus K., Nijboer J. American Association of Zoos and Aquariums; 2001. Okapi (Okapi johnstoni) SSP feeding guidelines.http://www.nagonline.net/HUSBANDRY/Diets%20pdf/Okapi%20Feeding%20SSP.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dambe L.M., Mogotsi K., Odubeng M., Kgosikoma O.E. Nutritive value of some important indigenous livestock browse species in semi-arid mixed Mopane bushveld, Botswana. Livest Res Rural Dev. 2015;(27):10. [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst R.J., Fisher W.J., Tweed J.K.S., Wilkins R.J. Comparison of grass and legume silages for milk production. 1. Production responses with different levels of concentrate. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:2598–2611. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierenfeld E.S., Atkinson S., Craig A.M., Walker K.C., Streich W.J., Clauss M. Mineral concentrations in serum/plasma and liver tissue of captive and free-ranging rhinoceros species. Zoo Biol. 2005;24:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gattiker C., Espie I., Kotze A. Diet and diet related disorders in captive ruminants at the national zoological gardens of South Africa. Zoo Biol. 2014;33:426–432. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghol B. Food and Agriculture Organisation of The United Nation; Rome, Italy: 1981. Tropical feeds. FAO animal production and health Series No. 12; p. 529. [Google Scholar]

- Grant C.C., Peel M.J.S., Zambatis N., Van Ryssen J.B.J. Nitrogen and phosphorus concentration in faeces: an indicator of range quality as a practical adjunct to existing range evaluation methods. Afr J Range Forage Sci. 2000;17:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gutzwiller A. University of Zurich; Switzerland: 1984. Beitrag zur Ernahrung der Zoosaugetiere. [Dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemzadeh-Cigari F., Khorvash M., Ghorbani G.R., Taghizadeh A. The effects of wilting, molasses and inoculants on the fermentation quality and nutritive value of lucerne silage. S Afr J Anim Sci. 2011;4:377–388. [Google Scholar]

- Hatt J.M., Clauss M. vol. 2. 2001. pp. 8–9. (Browse silage in zoo animal nutrition - feeding enrichment of browsers during winter. EAZA News. Special Issue on Zoo Nutrition). [Google Scholar]

- Hatt J.M., Clauss M. Browse silage in zoo animal nutrition: feeding enrichment of browsers during winter. In: Fidgett A., Clauss M., Eulenberger K., Hatt J.M., Hume I., Janssens G., Nijboer J., editors. Zoo anim nutrition. 2006. pp. 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Helander C., Nørgaard P., Arnesson A., Nadeau E. Effects of chopping grass silage and of mixing silage with concentrate on feed intake and performance in pregnant and lactating ewes and in growing lambs. Small Rumin Res. 2014;116:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann R.R. Evolutionary steps of ecophysiological adaptation and diversification of ruminants: a comparative view of their digestive system. Oecologia. 1989;78:443–457. doi: 10.1007/BF00378733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann R.R. East African Literature Bureau; Nairobi: 1973. The ruminant stomach: stomach structure and feeding habits of East African game ruminants. East African Monographs in Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Hooimeijer J.F., Jansen F.A., de Boer W.F., Wessels D., van der Waal C., de Jong C.B., Otto N.D., Knoop L. The diet of kudus in a mopane dominated area, South Africa. Koedoe. 2005;48(2):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Huisden C.M., Szabob N.J., Ogunadea I.M., Adesogana A.T. Mucuna pruriens detoxification: effects of ensiling duration and particle size. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2014;198:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman T., Azulai D., Engelhart K., Buijsert A., Nijboer J. Current feeding practices for captive okapi; how are guidelines used? 2008;4:26–27. EAZA Zoo Nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel J., Clauss M. Burgers' Zoo; Arnhem: 2006. Feeding. EAZA husbandry and management guidelines for Giraffa camelopardalis; pp. 29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel J., Südekum K.H., Streich W.J., Clauss M. Forage fermentation patterns and their implications for herbivore ingesta retention times. Funct Ecol. 2006;20:989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst W. Silage systems for the seventies. Soils and crops branch, Ontario Department of Agriculture and food. Rexdale: Ontario silage Conference. 1971. Principles of silage making. [Google Scholar]

- Izomkun-Etiobhio B.O., Ugochukwu E.N. Comparison of an alkaline picrate and pyridine-pyrazone method for determination of hydrogen cyanide in cassava and its products. J Sci Food Agric. 1984;35:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jamala G.Y., Tarimbuka I.L., Moris D., Mahai S. The scope and potentials of fodder trees and shrubs in agroforestry. J Agric Vet Sci. 2013;5:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kambatuku J.R., Cramer M.D., Ward D. Savanna tree-grass competition is modified by substrate type and herbivory. J Veg Sci. 2011;22:225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kibria S.S., Nahar T.N., Mia M.M. Tree leaves as alternative feed resource for Black Bengal goats under stall-fed conditions. Small Rumin Res. 1994;13:217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon J. Academic Press; CA: 1997. The kingdon field guide to african mammals. [Google Scholar]

- Klingelhoefer E.W. University of Pretoria; South Africa: 1987. Aspects of the ecology of elephant Loxodonta Africana (Blumenbach, 1797) and a management plan for the Tembe Elephant Park in Tongaland, KwaZulu. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Koc F., Ozduven M.L., Coskuntuna L., Polant C. The effects of inoculant lactic acid bacteria on the fermentation and aerobic stability of sunflower silage. Poljopr. 2009;15:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer J.M. University of Port Elizabeth; 2001. Dietary and Habitat resource use of indigenous kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) and introduced impala (Aepyceros melampus) in thicket vegetation, Eastern Cape. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance T. University of Guelph; Canada: 2012. An evaluation of browse silage production as a feed component for Zoo herbivores. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin S.R. Plant phenolics and their potential role in mitigating iron overload disorder in wild animals. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2012;43:74–82. doi: 10.1638/2011-0132.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louw G.N., Steenkamp C.W.P., Steenkamp E.L. Printer; Pretoria. S. Africa: 1968. Chemiese samestelling van die vernaaste plantspecies in die dorre, skyn-dorre, skynsukkulente en sentrale bo Karoo. Tech. Bull. No. 79. Dept. of Agric. Tech. Services, Govt. [Google Scholar]

- Lukhele M.S., Van Ryssen J.B.J. The chemical composition and potential nutritive value of the foliage of four subtropical tree species in southern Africa for ruminants. S Afr J Anim Sci. 2003;32:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mapiye C., Mwale M., Mupangwa J.F., Mugabe P.H., Poshiwa X., Chikumba N. Utilisation of ley legumes as livestock feed in Zimbabwe. Trop Grassl. 2007;41:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Martens S.D., Hoedtke S., Avila P., Heinritz S.N., Zeyner A. Effect of ensiling treatment on secondary compounds and amino acid profile of tropical forage legumes, and implications for their pig feeding potential. J Sci Food Agric. 2014;94(6):1107–1115. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbatha K.R., Lane E.P., Lander M., Tordiffe A.S.W., Corr S. Preliminary evaluation of selected minerals in liver samples from springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) from the National Zoological Gardens of South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2012;83:31–38. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v83i1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonald P. John Wiley and Sons Publications; Bath: 1981. The biochemistry of silage. [Google Scholar]

- Milewski A.V., Young T.P., Madden D. Thorns as induced defenses: experimental evidence. Oecologia. 1991;86:70–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00317391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muck R.E., Moser L.E., Pitt E.E. Postharvest factors affecting ensiling. In: Buxton D.R., Muck R.E., Harrison J.H., editors. Silage Science and technology, agronomy Monograph 42. American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America Inc., and Soil Science Society of America; Madison: 2003. pp. 251–304. [Google Scholar]

- Mugweni B.Z. University of Zimbabwe; Zimbabwe: 2000. The effect of feeding mixed maize-forage tree legume silages on milk production from lactating Holstein dairy cows. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwa T.A., Nsahlai I.V., Iji P.A. Ensilage as a means of reducing the concentration of cyanogenic glycosides in the pods of Acacia sieberiana and the effect of additives on silage quality. J Sci Food Agric. 2004;84:521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer J., Clauss M., Nobel J. Browse silage: the future for browsers in the wintertime? EAZA News, Zoo Nutrition Special Issue. 2003;3:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A., Olsson I., Lingvall P. Comparison between grass-silages of different dry matter content fed to reindeer during winter. Rangifer. 1996;16:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nussio L.G. Silage production from tropical forages. In: Park R.S., Stronge M.D., editors. Silage production and utilisation. Wageningen Academic Publishers; Wageningen: 2005. pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith N. Comparative mortality rates of male and female Kudus: the costs of sexual size dimorphism. J Anim Ecol. 1993;62(3):428–440. [Google Scholar]

- Paglia D.E., Dennis P. Proceedings, Annual Conference of the American association of zoo veterinarians. Columbus, Ohio. 1999. Role of chronic iron overload in multiple disorders of captive black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis) pp. 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Palgrave K.C. Struik Publishers; Cape Town: 1977. Trees of southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Palgrave K.C., Drummond R.B., Moll E.J., Palgrave M.C. Euphorbia L. In: Moll E.J., editor. Trees of Southern Africa. Struik Publishers; Cape Town: 2002. pp. 523–535. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer E., Pitman N. Balkema; Cape Town: 1972. Trees of southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Parker D.M., Bernard R.T.F. The diet and ecological role of giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) introduced to the Eastern Cape. S Afr J Zool. 2005;267:203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Parks S.E., Haigh A.M., Creswell G.C. Stem tissue phosphorus as an index of the phosphorus status of Banksiaeri cifolia L. Plant Soil. 2000;227:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pellew R.A. The production and consumption of Acacia browse and its' potential for animal protein production. In: Le Houérou H.N., editor. Browse in Africa. ILCA; Ethopia: 1980. pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri M.S., Ngongoni N.T., Maasdorp B.V., Titterton M., Mupangwa J.F., Sebata A. Ensiling characteristics and feeding value of silage made from browse tree legume-maize mixtures. Trop Subtrop Agroecosyst. 2007;7:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Polis G.A. Why are parts of the world green? Multiple factors control productivity and the distribution of biomass. Oikos. 1999;86:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Popplewell W.L., Marais E.A., Brand L., Harvey B.H., Davies-Coleman M.T. Euphorbias of South Africa: two new phorbol esters from Euphorbia bothae. S Afr J Chem. 2010;63:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez R.G. Nutrient digestion and nitrogen utilization by goats fed native shrubs Celtis pallida, Leucophullum texanum and Porlieria angustifolia. Small Rumin Res. 1998;28:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins C.T., Spalinger D.E., Van Hoven W. Adaptation of ruminants to browse and grass diets: are anatomical-based browser-grazer interpretations valid? Oecologia. 1995;103:208–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00329082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosic J., Estell R.E., Ivankovic S., Kezic J., Razov J. Potential mechanisms to increase shrub intake and performance of small ruminants in Mediterranean shrubby ecosystems. Small Rumin Res. 2007;74:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo G., Martínez-Suller L., Arriaga H., Merino P. Effects of forage supplements on milk production and chemical properties, in vivo digestibility, rumen fermentation and N excretion in dairy cows offered red clover silage and corn silage or dry ground corn. Ir J Agric Food Res. 2010;49:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Scogings P.F., Dziba L.E., Gordon I.J. Leaf chemistry of woody plants in relation to season, canopy retention and goat browsing in a semiarid subtropical savannah. Austral Ecol. 2004;29:278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Shane M.W., Cramer M.D., Funayama-Noguchi S., Cawthray G.R., Millar H.A. Developmental physiology of cluster-root carboxylate synthesis and exudation in Hakea prostrata R. Br.. (Proteaceae): expression of PEP-carboxylase and the alternative oxidase. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:549–560. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.035659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair A.R.E., Simon C.P., Mduma A.R., Serengeti Fryxell JM., III . Dynamics University of Chicago Press; USA: 2009. Human impacts on ecosystem. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.E., Chavey P.S., Miller R.E. Iron metabolism in captive black (Diceros bicornis) and white (Ceratotherium simum) rhinoceroses. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1995;26:525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Songca S.P., Ramurafhi E., Oluwafemi O.S. A pentacyclic triterpene from the leaves of Combretum collinum Fresen showing antibacterial properties against Staphylococcus aureus. Afr J Biochem Res. 2013;7(7):113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava L.M. Academic Press; Oxford: 2002. Plant growth and development. Hormones and the environment. [Google Scholar]

- Stapelberg H., Van Rooyen M.V., Bothman J.P. Spatial and temporal variation in nitrogen and phosphorus concentration in faeces from springbok in the Kalahari. J Wildlife Res. 2008;38:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tainton N. University of Natal Press; South Africa: 2000. Pasture management in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira A.A., Rich E.C., Szabo N.J. Water extraction of L-dopa from Mucuna bean. Trop Subtrop Agroecosystems. 2003;1:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Titterton M., Bareeba F.B. Grass and legume silages in the tropics. In: silage making in the Tropics with particular emphasis on smallholders. In: t'Mannetje L., editor. Silage making in the tropics with particular emphasis on Smallholders... 1 September to 15 December 1999. FAO plant production and protection paper 161. Food and Agricultural Organization; Italy: 2000. p. 2000:43. [Google Scholar]

- Tjandraatmadja M., Norton B.W., Mac Rae I.C. Ensilage of tropical grasses mixed with legumes and molasses. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;10:82–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00357569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood E.J., Suttle N.F. 3rd ed. CABI Publication; UK: 1999. The mineral nutrition of livestock. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eps A.W., Pollitt C.C. Equine laminitis induced with oligofructose. Equine Vet J. 2006;38:203–208. doi: 10.2746/042516406776866327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest P.J., Dierenfeld E.S., Conlink L.N. Ruminant physiology: digestion, metabolism, growth and reproduction.W. von Engelhardteditor Proc. VIII. Int. Symp. On Ruminat Physiol. Ferdinand Enke Verlag; Berlin/New York: 1995. Digestive strategies and limitations of ruminants; pp. 579–597. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk B., Van Wyk P., Van Wyk B.E. Briza Publications; South Africa: 2000. Trees of southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Vercammen F., de Deken R., Brandt J. The effect of dietary sugar content on glucosuria in a female okapi (Okapi johnstoni) In: Fidgett A., Clauss M., Eulenberger K., Hume I., Janssens G., Nijboer J., editors. Zoo animal nutrition, Volume III, Germany. Filander Verlag; Fürth: 2006. pp. 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wanjekeche E., Wakasa V., Mureithi J.G. Effect of germination, alkaline and acid soakingand boiling on the nutritional value of matureand immature mucuna (Mucuna pruriens) beans. Trop Subtropi Agroecosystems. 2003;1:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wensvoort J. Browse silage in the United Arab Emirates. Wildlife Middle East News. 2008;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- White E.P. Legumes examined for alkaloids – additions and corrections. N Z J Sci Technol. 1951;33:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J.M., Davies D.R. The aerobic stability of silage: key findings and recent developments. Grass Forage Sci. 2012;68:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Woolford M.K. Marcel Dekker Inc; New York and Basel: 1984. The silage fermentation. [Google Scholar]

- Wright J.B. Cornell University; Africa. NY: 1998. A comparison of essential fatty acids, total lipid, and condensed tannin in the diet of captive black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis) in North America and in browses native to Zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- Zenker W., Clauss M., Huber J., Altenbrunner M.B. Rumen pH and hoof health in two groups of captive wild ruminants. In: Clauss M., Fidgett A., Hatt J-M., Huisman T., Hummel J., NijboerJ, Plowman A., editors. Zoo animal nutrition IV. Filander Fürth, Verlag; Fürth, Germany: 2009. pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]