Abstract

The advent of adaptive manufacturing techniques supports the vision of cell-instructive materials that mimic biological tissues. 3D jet writing, a modified electrospinning process discovered herein, yields three-dimensional structures with unprecedented precision and resolution offering customizable pore geometries and scalability to over tens of centimeters. These scaffolds support the 3D expansion and differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Implantation of these constructs leads to the healing of critical bone defects in vivo without exogenous growth factors. When applied as a metastatic target site in mice, circulating cancer cells homed in to the osteogenic environment simulated on 3D jet writing scaffolds, despite implantation in an anatomically abnormal site. Through 3D jet writing, we demonstrate the formation of tessellated microtissues which serve as a versatile 3D cell culture platform in a range of biomedical applications including regenerative medicine, cancer biology, and stem cell biotechnology.

Keywords: electrospinning, microtissue, 3D cell culture, tissue engineering, cancer

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering aims to recreate biological function by habituating one or more types of human cells to a supporting scaffold construct with appropriate biological, physical and mechanical properties.[1] Recent progress with adaptive manufacturing processes, including 3–4D printing and optical patterning, supports the vision of synthetically prepared, cell-instructive material systems that mimic many of the structural aspects of biological tissues.[2] To date, this vision has been restrained from realization by technological tradeoffs between the level of exerted architectural control and the requirement for specialized, typically biologically incompatible materials. A modified electrospinning process, 3D jet writing, is herein demonstrated to yield three-dimensional structures with unprecedented precision and resolution from clinically relevant polymers. Electrospinning of polymer solutions has been widely used in the past for preparing tissue engineering scaffolds,[3] albeit the resulting structures are randomly deposited fiber networks with sub-micron sized pores that prevent effective cell infiltration. In electrospinning, the random deposition of fibers is caused by inherent whipping instabilities, which arise from counteracting physical forces that act upon the depositing fiber jet.[4] Recent attempts to improve the control of fiber deposition have taken advantage of rotating collectors,[5] secondary electrodes,[6] and patterned collection electrodes,[7] but 3D scaffolds containing regularly tessellated structures over larger areas have yet to be demonstrated.[8] The processing of polymer melts, instead of polymer solutions, both with [9] and without [10] electrical fields, can significantly improve the obtainable levels of scaffold precision. However, polymer melts involve high processing temperatures, typically in the range of 80 – 300°C, which are incompatible with most biodegradable polymers used in regenerative medicine [11] and virtually all biological materials, such as proteins or even small molecule drugs.[12] Similarly, emerging techniques such as cell electrospinning are not compatible with melt electrospinning.[13]

In contrast, 3D jet writing produces regularly tessellated structures from solutions of a common biodegradable and bicompatible polymer, poly(lactide-co-glycolide) or PLGA, with unmatched spatial precision and 3D resolution. During 3D jet writing, extraordinary jet stability is achieved through implementation of a secondary electrode that, in conjunction with a 2D motion platform, allows for controlled focusing and stacking of continuously deposited microfibers into open-pore architectures. This setup allows for the precise manufacturing of custom-defined geometries. To minimize cell contact with polymeric material, mechanically robust honeycomb pore structures with maximal open pore volume were selected as target architecture for fiber-based tissue constructs (Figure 1).[14]

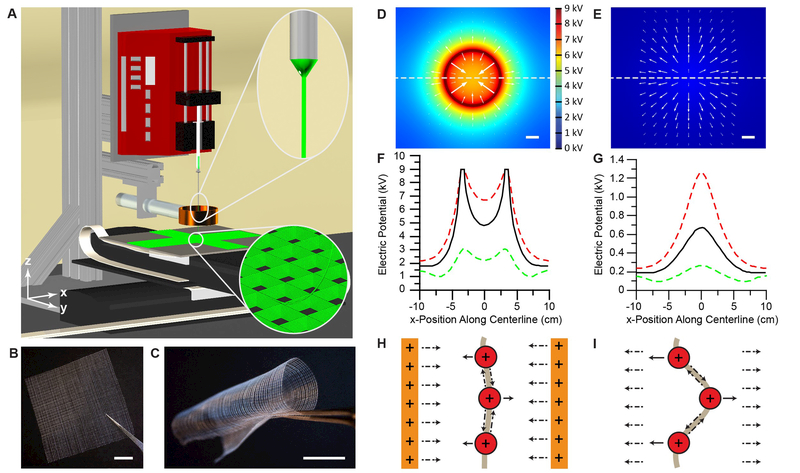

Figure 1. The 3D jet writing process yields precisely engineered fiber constructs.

(A) The 3D jet writing setup: An electrostatic lens effectively focuses the deposition of the fluid jet and computer directed stage movement allows for fibers to be organized into complex 3D patterns (bottom inset). (B-C) Examples of large-scale square patterned structures made by 3D jet writing. (D-E) Computer simulations of the electric potential in the x-y plane 3 cm below the tip of the orifice with (D) and without (E) a secondary electrode (acting as an electrostatic lens). The direction of the electric field at various points is indicated by white arrows. (F-G) Modeling of the electric potential along the x-axis marked by the dashed line in (D) and (E) illustrates the electric potential distribution both with (D) and without (E) a secondary electrode. Here red, black, and green lines represent a z-position 2, 3, and 4 cm below the capillary orifice, respectively. (H) The lens effect of the secondary electrode in (D) and (F) is demonstrated by the formation of an electric potential well, which drives the fiber towards the center of the secondary electrode. (I) In contrast, lack of a secondary electrode results in deflection of the fiber from the centerline which is the premise of the whipping instability. Scale bars represent 1 cm.

2. Spatially and temporally controlled fiber deposition

The electrospinning process is typically characterized by an inherent whipping instability which arises from the applied electric potential. In brief, a high electric potential deforms a fluid droplet resting at the orifice of the needle into a conical droplet, called the Taylor cone. A charged fluid jet emits from the Taylor cone, and accelerates towards a grounded collection electrode, which causes an electric potential maximum exactly below the capillary tip (Figure 1 G). The resulting electric field points radially outward (Figure 1 E), initiating jet movement towards the periphery [15] and deposition of randomly oriented polymer fibers (Figure 1 I). [4, 16]

Fundamentally, creating 3D microfiber structures via electrospinning required stabilization of the whipping instability during jet propagation and fiber deposition. Outward directed jet movement was suppressed by a secondary electrode,[6] as detailed by finite element analysis of the electric field in the 3D jet writing system: (i) A circular secondary ring electrode modified the electric potential profile by creating an electric potential well, which inverted the direction of the electric field towards the center of the electrode (Figure 1 D, F, S1–S10). (ii) This electric field was associated with an inward directed force, which acted on the electrically charged fluid jet and effectively suppressed the initiation of the whipping instability (Figure 1 H).[6b] (iii) Experimentally, the realization of the ultra-stable polymer jet and the absence of discernible whipping instabilities (Figure S11 and S12) ensured precise targeting of the depositing fiber onto the scaffold (Table S1, Movie S1).

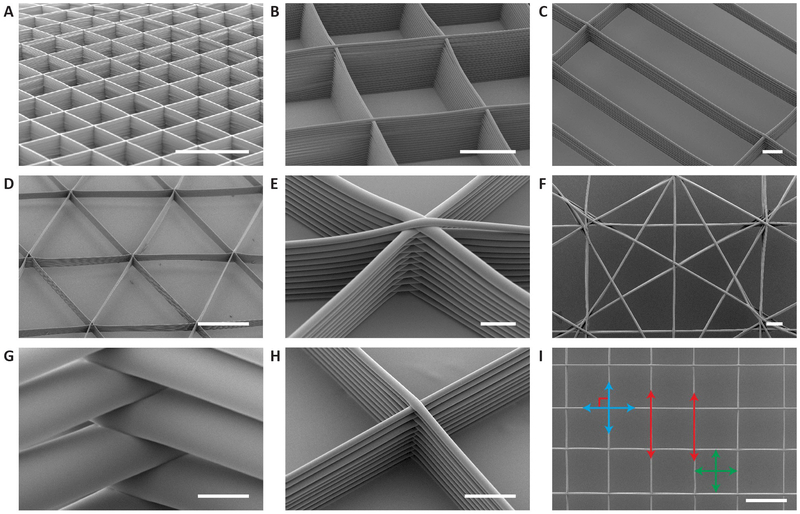

The polymer fiber was then patterned into open-pore structures (Figure 1 A – C, S11 – S16). Regular lattices were generated with tessellated, cuboid pore geometries (Figure 2 A, S16) of precisely configurable aspect ratios (Figure 2 B, C). Tessellation of prismatic pores formed honeycomb structures with unprecedented material-to-total volume ratios, i.e. relative densities that are well-below 5%.[17] The control of fiber orientation during the 3D jet writing process resulted in a spectrum of alternative pore geometries (Figure 2 D – F). Alteration of the electric field controllably yielded fiber radii between 3 – 25 μm (Figure S15), creating mechanically stable scaffold structures with relative densities that were as low as 3% (Figure 2 H-I), as well as geometric features sizes on the order of 70–100 μm (Figure 2 G). We further note that 3D jet writing achieved alignment of parallel fibers within 0.3° and perpendicularity of fibers within 1.1°, while producing geometric features, which are consistent within 5% (Figure 2 I, S17).

Figure 2. SEM images of tessellated scaffold structures manufactured by 3D jet writing.

(A-D) Adaptive manufacturing of different geometries such as tessellated arrays of squares with heights up to 400 µm (A-B), rectangles with dimensions of 300 µm x 1200 µm (C), and isosceles triangles (D). (E) Fiber stacks consist of interwoven fibers which are layered on top of one another. A high level of precision in fiber placement is revealed at the intersections of fiber stacks. (F) Non-regular arrays of shapes with characteristic features in the range of 100 µm. (G-H) Fiber diameters ranged from 50 µm (G) to 6 µm (H). (I) SEM image of a representative portion of a structure used to determine the parallelism, perpendicularity, and geometric consistency of the PLGA fiber stacks patterned by 3D jet writing. Error reported is the average root mean square error of the three scaffolds measured. Scale bars represent 1 mm (A), 500 µm (B, D, I), 100 µm (C, F), 50 µm (E, G-H).

3. Stem cell culture in tessellated 3D scaffolds

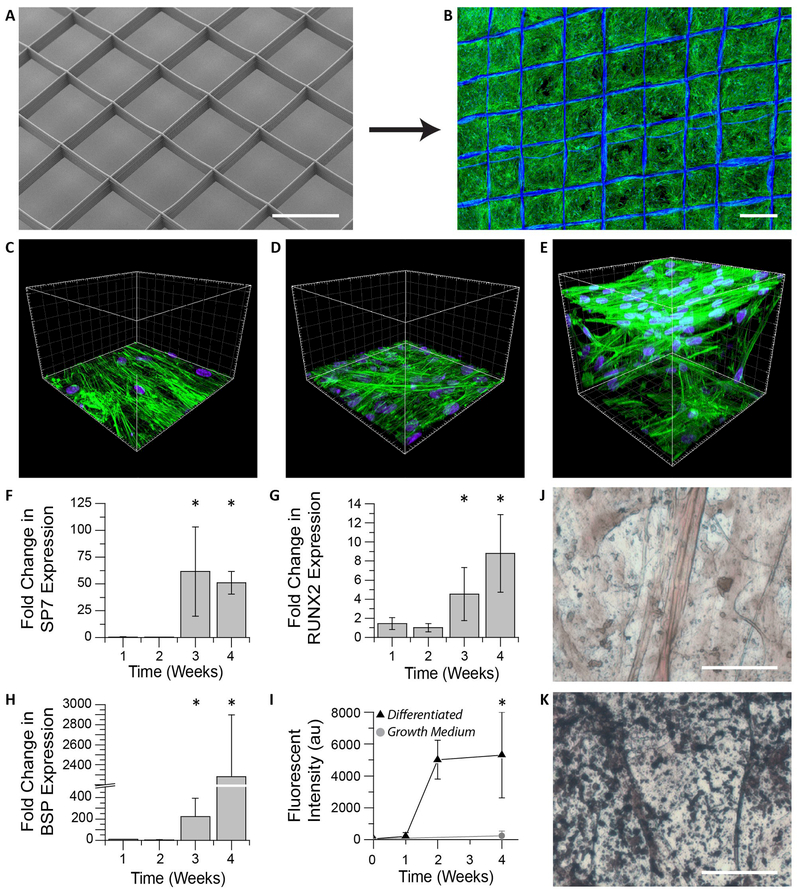

Past research with a wide range of biodegradable scaffold materials of natural [1c, 18] and synthetic origin [1a, 1b, 19] suggests that open-pore scaffolds that minimize the interactions between cells and the scaffold are preferential,[20] because they promote increased cell-cell interactions that give rise to natural development. Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were cultured on regular square honeycomb scaffolds with 500×500 μm pores and 5% relative density (Figure 3 A – B). Over the course of three days, cells filled the entire free volume of the scaffold (Figure 3 B) resulting in a cell density of 1.4 × 106 cells/mm3 PLGA, upwards of seven times higher than previously reported.[21] The combined effect of high cell density culture on scaffolds of low relative density implies minimal cell contact with polymeric material but maximal cell-cell contact (Figure 3 E). Physiological relevance was thus improved on tessellated scaffolds relative to the 2D cultures on either randomly deposited fiber mats (Figure 3 D) or cell culture dishes (Figure 3 C).[1a, 22] Where required, 3D jet writing was scaled over large areas (5×5 cm) with user-defined scaffold footprints (Figure S18) and precisely controlled thicknesses.

Figure 3. In vitro hMSC culture on 3D jet writing scaffolds produces 3D microtissues.

(A-B) 3D microfiber scaffolds were incubated with fibronectin and seeded with hMSCs to yield confluent cell structures. (C-E) hMSCs cultured on scaffolds (E) reveal significantly different morphologies and spatial distribution (3D) than cultures on glass (C), or non-woven PLGA fiber mats (D) (both 2D). (F-H) hMSCs on scaffolds were incubated in osteogenic differentiation media and monitored using qPRC. The markers SP7 (F), RUNX2 (G), and BSP (H), were used as indicators of osteogenic differentiation. Values reported are fold increases over hMSCs cultured in growth medium. Large increases in these markers after three weeks is consistent with the onset of osteogenesis. Error bars represent ±Std. Dev from three independent experiments. (I) Fluorescent staining of scaffolds for hydroxyapatite reveal substantial increases in matrix mineralization after two weeks of differentiation. (J-K) Von Kossa staining of hMSCs incubated in growth medium (J) showed little matrix mineralization compared to that seen in samples differentiated in osteogenic induction medium indicated by the black aggregates (K). Scale bars represent 500 µm (A-B), 50 µm (J-K), and the spacings between large grids are 20 µm (C-E).

4. On-scaffold stem cell differentiation into tessellated microtissues

In addition to controlling the local architecture, mechanical reinforcement of the 3D microtissues by the fiber scaffold ensured ease of handling, while the open honeycomb pore structure allowed for compatibility with standard fluorescent assays, histology, confocal microscopy, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Osteogenic differentiation of confluent hMSC structures (Figure 3B) was confirmed by expression of the osteogenic markers runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), bone sialoprotein (BSP), and osterix (SP7) [23], which were monitored over the course of four weeks by qPCR (Table S2). By week three, the expression of all three genes showed a significant increase (p<0.05) relative to controls (Figure 3 F – H). A substantial increase in hydroxyapatite deposition was observed after two weeks based on a fluorescent hydroxyapatite maker (Figure 3 I). In addition, Von Kossa staining verified a substantial increase in matrix mineralization after four weeks (Figure 3 K) compared to controls, which were maintained in hMSC growth medium (Figure 3 J). The combination of increased expression of the osteogenic markers and enhanced matrix mineralization indicated that the hMSCs were differentiated towards an osteogenic lineage.[23–24]

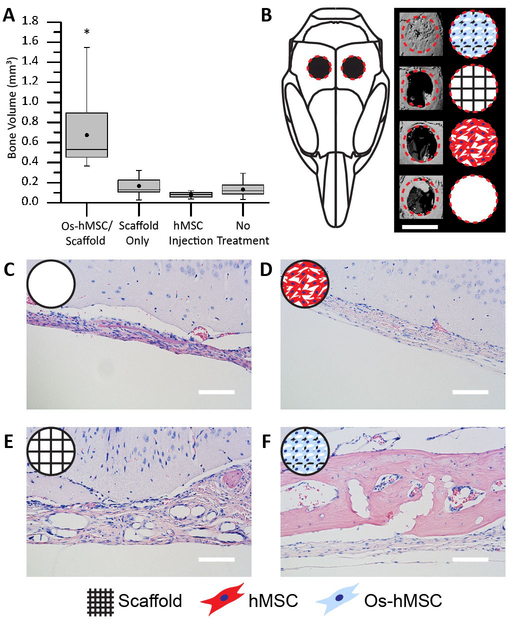

5. Tissue regeneration of calvarial defects

The ability of the tessellated microtissue arrays to regenerate tissue in vivo was next assessed in a critical calvarial defect mouse model.[25] The following treatments were administered to the defect sites: 1) no treatment, 2) a PLGA scaffold, 3) a PLGA scaffold with osteogenically differentiated hMSCs (Os-hMSC), and 4) an equivalent injection of undifferentiated hMSCs (Figure S19). After treatment, analysis by micro computerized tomography (microCT) revealed that the Os-hMSC group was capable of completely closing the critical defect site (Figure 4 B). The remaining groups showed minimal new bone growth which was largely restricted to the periphery of the defect (Figure 4 B). Quantification of the microCT demonstrated that the Os-hMSC samples had induced significantly more new bone volume than the other treatment methods (Figure 4 A). This result was further confirmed by histological analyses showing significant new bone volume only for the Os-hMSC group (Figure 4 C – F, Figure S20). Overall, these results illustrated that neither cells nor scaffolds alone were sufficient to heal the defect. Instead, the delivery of hMSCs differentiated directly on 3D jet writing scaffolds proved most efficacious, producing the highest volume of new bone within the defect and showing potential to close the defect site, even in the absence of bone-promoting growth factors such as bone morphogenic protein. We attribute the improved healing of the defect to the increased preservation of cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts, and higher cell densities in the tessellated scaffold structures.[26]

Figure 4. 3D jet writing scaffolds regenerate bone tissue in vivo.

Two 3 mm defects were placed in the parietal bone of a mouse skull to create a critical bone defect. (A) MicroCT was used to quantify the new bone volume within the defect area. The box plot shows the mean (dot), median (middle line), standard error (top and bottom of the boxes), and the max/min (whiskers) for each group. (*) indicates statistical difference as determined by a Tukey multi-comparison test. (B) 3D reconstruction of the microCT data was performed to visualize the defect area. From top to bottom, sample groups are: hMSCs osteogenically differentiated directly on the scaffold or Os-hMSC, scaffold alone without cells, injection of an equivalent number of non-differentiated hMSCs, and no treatment. (C-F) Histological samples from the calvarial defect model were stained with hemotoxylin (blue, nuclear stain) and eosin (pink, protein stain). When scaffolds with osteogenically differentiated stem cells (Os-hMSC) were implanted, there was significant new bone formation, and PLGA fibers embedded in the new bone are shown in (F). Other groups show that treatment with only a PLGA fiber scaffold implant (E) or hMSC injections (D) yield little to no improvement over no treatment (C). Histology and microCT images are from the best sample for each group. Scale bars represent 3 mm (B), 100 µm (C-F).

6. Cancer-to-bone metastasis

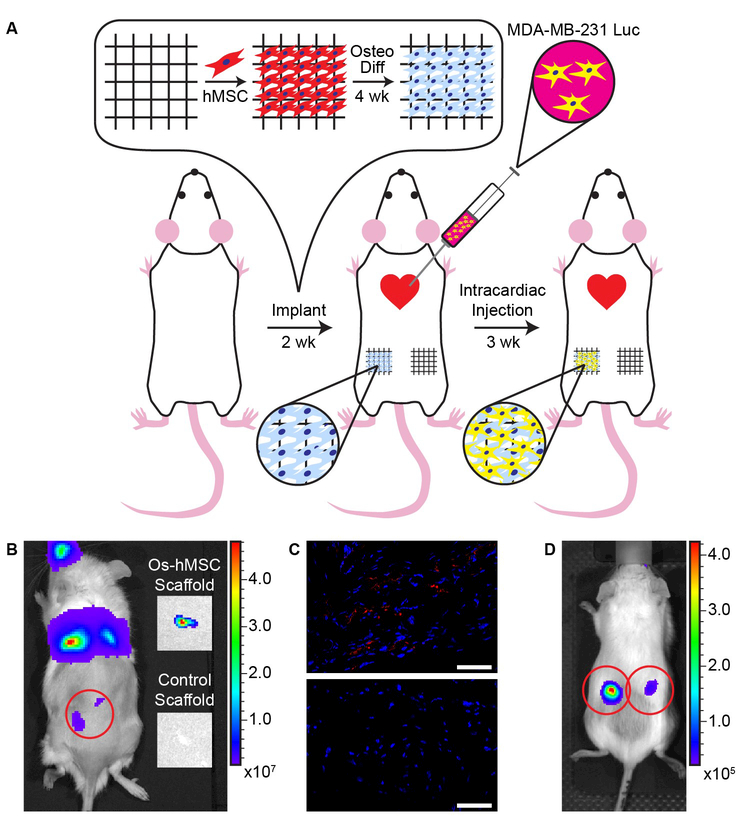

Beyond tissue regeneration, osteogenically differentiated hMSC scaffolds were assessed for biological relevance in application as a disease model for cancer metastasis.[27] We hypothesized that subcutaneous implantation of 3D osteogenic microtissues into mice would create a metastatic environment at an anatomically unnatural site. Regular square honeycomb scaffolds were seeded with hMSCs, osteogenically differentiated for 4 weeks, and inserted into the flank of 6–10 week old female NSG mice (N=5 mice per group). The flank was selected as the implantation site, because metastases are typically not observed in this tissue, allowing for effective determination of implant efficacy and bioluminescent monitoring. Two weeks after implantation, luciferase expressing MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were administered to the mice via intracardiac injection (Figure 5 A).[27b, 28] Bioluminescence (Figure 5 B, D) and immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 5 C) confirmed metastasis of MDA-MB-231 cells in 5/5 osteogenically differentiated hMSC implants, while only 2/5 controls (cell-free scaffolds with fibronectin) showed evidence of metastases. This model demonstrates that our engineered osteogenic microtissues effectively simulate a bone environment where injected human breast cancer cells metastasized to as evidenced in all mice after introduction of the cancer cells. This further validates the physiological relevance of the tessellated microtissues generated on 3D jet writing scaffolds.

Figure 5. Metastatic cancer cells accumulate in bone scaffolds placed at an abnormal site in vivo.

(A) Experimental layout of the cancer metastasis study. hMSCs were cultured for 7 days on the scaffold in growth medium, and subsequently differentiated for four weeks in osteogenic differentiation medium. The scaffolds carrying differentiated cells were implanted subcutaneously in the rear flank of the mouse. On the contralateral flank, scaffolds containing only fibronectin were implanted. Two weeks after implantation, an intracardiac injection of luciferase expressing MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells was administered. Tumor progression was monitored for three weeks, and scaffolds were removed 25 days post-injection. (B) Subcutaneous scaffolds seen under bioluminescent imaging were explanted and re-imaged post explanation. Explanted scaffolds containing osteogenically differentiated cells showed bioluminescent signal, while the protein coated scaffolds did not. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of histological sections of the explanted scaffold reveals the presence of FLAG (red), an epitope which was attached to the luciferase to aid in identifying injected cancer cells. Nuclei of the cells are indicated in blue. (D) Bioluminescent imaging of a mouse after implantation of scaffolds with osteogenically differentiated cells in its left and right flank. Scale bars indicate 50 µm.

7. Conclusion

Precise manufacturing of biocompatible microfiber scaffolds by 3D jet writing affords architectures comprised of tessellated pore geometries. These highly organized open frameworks maintain mechanical integrity throughout long term in vitro culture and in vivo implantation, while minimizing synthetic material. Tessellation of 3D microtissues across user-defined areas, while maintaining cell-cell interactions, was demonstrated to mimic biological systems in tissue regeneration and cancer metastasis models. This work establishes a key technological progress over conventional electrospinning with respect to precission and control and hast he potential to catapult electrohydrodynamic jetting technologies to the forefront of adaptive micromanufacturing technologies for 3d tissue engineering. Going forward, the full exploration of the capabilities of 3D jet writing as a physiologically relevant 3D cell culture platform will provide insight into an array of biotechnological applications.

8. Experimental Section

Materials:

The following materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich: Poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (MW 50–75 kg/mol) for scaffold fabrication, and the co-jetting solvents chloroform, and N,N-dimethylformamide.

Electrohydrodynamic Co-Jetting:

Jetting solution for creating bicompartmental microfibers consisted of 30 w/v% PLGA dissolved in 93:7 v/v% chloroform:N,N-dimethylformamide. Each compartment contained a different fluorescent probe at a concentration <0.01 w/v%. Jetting solutions were loaded into syringes and pumped through side-by-side capillaries via a syringe pump (Fischer Scientific). A copper secondary electrode (5 cm in diameter, 2.5 cm in height, and 1.5 mm thick) was secured beneath the capillaries. Capillaries were placed nominally 5 cm above the collector, with the lens positioned 0.5 cm below the capillary tip. A positive potential was applied using DC power supplies (Gamma High-Voltage Research ES30P-20W). A nominal potential of16 kV and 9kV was applied to both the capillaries and the secondary ring electrode, respectively. Fibers were jetted onto a grounded electrode consisting of a stainless-steel plate, aluminum foil, or silicon wafer. Two linear motion stages were implemented, one stage for x and y motion respectively (ILS-300LM, Newport Corporation). A 4-axis universal controller (XPS-Q4, Newport Corporation) coupled with LabView software synchronized the stage movements. For additional details see Supplementary Methods.

Simulations:

COMSOL simulations were used to visualize the electric potential and electric fields in the 3D jet writing system. All components were pre-defined in the COMSOL materials library, and were drawn to scale. Electric potentials were calculated using finite-element analysis. Boundary conditions used are given in the description of 3D jet writing.

Fibronectin preparation:

Human fibronectin (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) was diluted to a concentration of 100 µg/ml in magnesium and calcium free cold Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS). The scaffolds were coated overnight at 30°C and stored at 4°C until use.

Cell culture media preparation:

Culture medium for hMSCs was composed of low glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% MSC qualified FBS, 1% Penicillin Streptomycin, and 10 ng/ml human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) prior to use. Osteogenic medium was prepared using an hMSC osteogenic bullet kit (Lonza group, Basel Switzerland). hMSC differentiation basal medium was supplemented with dexamethasone, L-glutamine, ascorbate, penicillin streptomycin, mesenchymal cell growth serum, and β-glycerophosphate per the manufacturer’s recommendation.

hMSC Expansion:

hMSCs (Lonza, Basel Switzerland) expansion were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2 and cultured at 37ºC in 5% CO2. The medium was replaced every 3–4 days and the cells were passaged when they were approximately 80% confluent. All cells used in the studies were passage 5 or less. Once seeded onto the scaffolds, medium was replaced every 3 days.

Cell culture on scaffolds:

750 µm square pore scaffolds were coated with fibronectin, and then seeded with hMSCs overnight at a concentration of 200,000 cells/scaffold. Once seeded, the scaffolds were transferred to a low adhesion dish and maintained at 37˚C in 5% CO2 until a confluent volume of cells was attained. The confluent scaffolds were then given osteogenic differentiation medium (Lonza Group Ltd, Basil, Switzerland) which was replaced every three days for the duration of the study. For qPCR analysis, the cells were lysed on the scaffolds and mRNA was collected using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg).

Cell staining:

Actin was labeled using Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin. First, cells on scaffolds were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 h and then permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Blocking was performed using 5% BSA for at least 30 m. A 0.33 µM solution of Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin was added to the scaffold for 1 h, then the solution was washed with PBS. Finally, the cell nucleus was stained using a 2µM solution of TO-PRO-3 Iodide, and then washed using PBS.

Von Kossa staining (American MasterTech, Lodi, CA) was performed on fixed scaffolds by first washing the scaffolds in DI water. The scaffolds were then placed in a 5% silver nitrate for 45 minutes under exposure with a UV light. The scaffolds were then rinsed using distilled water and placed in 5% sodium thiosulfate for 3 minutes and then rinsed using tap water. Finally, the scaffolds were placed in nuclear fast red stain for 5 minutes and washed with tap water before imaging.

RNA isolation:

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg). RNA was obtained immediately before the cells were seeded onto the scaffolds and weekly after expansion on the tissue engineered constructs. Briefly, cells were lysed directly on the scaffolds using cell lysis buffer RLT. The cell lysate was then homogenized using a QIAshredder spin column, and the RNA was isolated using RNeasy spin columns. RNA concentration and quality was determined using a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Samples with RNA concentrations less than 2 ng/μl, with an OD 260/280 less than 1.8, and OD 260/230 less than 2.0 were not analyzed and a replacement sample was used.

qPCR analysis:

Changes in ostegenic markers (Table S2) were evaluated using the TaqMan gene expression assay system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The StepOne Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) with TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) were used to conduct real time PCR in triplicate for each sample. GAPDH was amplified as an internal standard and quantification was performed using the comparative CT method (Table S2).

Calvarial defect model:

Use and care of the animals used in this study followed the guidelines established by the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine before the surgery as an analgesic. The skin on the head of the mouse was disinfected with a 70% ethanol solution. Two 3 mm-defects were created in the left and right parietal bone of the skull with a trephine bur. Four treatment regimens were administered to the defect site: 1) No treatment, 2) PLGA microfiber scaffold, 3) PLGA microfiber scaffold with a cultured volume of human mesenchymal stem cells which had been differentiated using osteogenic media in situ for two weeks, 4) injection of non-differentiated human mesenchymal stem cells. Treatment options were administered directly to the defect site. Circular cutouts of PLGA microfiber scaffolds with and without cells were made using a 3mm tissue punch. Three circular cutouts were stacked on top of one another to achieve a comparable thickness to the defect. hMSC injections, containing the same number of cells as the PLGA microfiber scaffolds with differentiated hMSCs, were suspended in a volume of saline equal to the volume of three PLGA microfiber scaffold cutouts. After implantation, the overlying tissue was surgically stapled over the defect area and allowed to heal for 8 weeks. After 8 weeks, the mice were euthanized for further analysis.

Metastatic Cancer Model:

The University of Michigan IACUC approved all animal procedures performed in this study. We implanted osteogenic scaffolds or control scaffolds coated with fibronectin into subcutaneous tissues of backs of 8–10 week-old female NSG mice (Jackson Laboratory) (n = 5 per experiment). Two weeks after implanting scaffolds, we injected 1 × 105 MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells (ATCC) directly into the left ventricle of mice to produce systemic metastases.[28a] We used MDA-MB-231 cells stably transduced with a lentiviral vector for FLAG labeled click beetle green luciferase to enable bioluminescence imaging and histological analysis.[28b] We imaged living mice with an IVIS Spectrum instrument (Perkin-Elmer) to detect metastases as described.[28c] When mice had to be euthanized for tumor burden, we injected luciferin immediately before euthanizing each animal and then imaged metastatic foci ex vivo as we have reported previously.[28a]

Tissue Preparation and Histology:

Extracted samples were placed in Z-fix (Anatech Ltd.) for three days, and were subsequently stored in 70% ethanol until microCT imaging was completed. Prior to histological processing, samples were decalcified in a 10% EDTA solution in DI water (adjusted to pH7 with NaOH). Decalcified samples were embedded in paraffin and 10 µm sections were taken at the middle of the defect. Sections were stained using hemotoxylin and eosin for light microscopy observation.

Anti-FLAG staining of paraffin embedded tissue samples containing the explanted scaffolds, both the fibronectin coated control and osteogenically differentiated hMSCs, were deparaffinized by soaking the slides in two changes of xylene for five minutes each. An ethanol ladder was used to rehydrate the tissue sample, with three-minute washes in 100%, 100%, 95%, 70%, 50% ethanol respectively. This was followed by a ten-minute soak in a 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The slides were then rinsed two time, for five minutes each, in PBS. Antigen retrieval was accomplished via a ten-minute incubation in 95 – 100°C citrate buffer at pH 6.0. After cooling for 20 minutes, the slides were then washed two times for five minutes in PBS. The tissue sections were circled with wax, and blocked for 1 hr in blocking buffer (10% bovine serum albumin in DI water). Slides were then washed two times for two minutes in PBS, and then droplets of diluent (1% bovine serum albumin in DI water) were incubated on the sections for five minutes. The excess diluent was removed from the slide, and primary antibody (anti-FLAG produced in rabbit) diluted in the diluent to a concentration of 10 µg/ml. Droplets of the primary antibody were placed on the tissue sections for 60 minutes, and the slides were rinsed two times for five minutes in PBS. This was followed by incubation of the tissue sections in secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG produced in goat) diluted in diluent at 10 µg/ml for 30 minutes. After secondary antibody incubation, slides were washed twice in PBS for five minutes, and subsequently counterstained using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a 2 µg/ml concentration. Slides were then rinsed under running tap water for 15 minutes, and subsequent dehydration using an alcohol ladder consisting of 50%, 70%, 95%, 95%, 100%, 100% washes respectively, each for five minutes. Slides were then cleared by incubating in three xylene washes for two minutes each. Once dried, ProlongGold was used to mount a cover slip to the slide, and allowed to cure for 24 hours prior to confocal imaging. Negative controls were performed without the use of a primary antibody to ensure non-specific binding of the secondary antibody to the tissue sections was not occurring.

MicroCT:

Specimens were embedded in 1% agarose and placed in a 34 mm diameter tube and scanned over the entire length of the calvariae using a microCT system (µCT100 Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). Scan settings were: voxel size 18 µm, 70 kVp, 114 µA, 0.5 mm AL filter, and integration time 500 ms. Analysis was performed using the manufacturer’s evaluation software, and a fixed global threshold of 18% (280 on a grayscale of 0–1000) was used to segment bone from non-bone. A 3 mm diameter cylindrical ROI was centered over the defect in the calvariae to determine the amount of bone regeneration at the site.

Statistics:

Statistical significance was determined by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA, p<0.05). A Tukey multi-comparison test was used to distinguish differences between groups. Minitab was used to perform all statistical analyses. All data is reported as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support by NIH’s Physical Sciences-Oncology Network through a UO1 grant (U01 CA210152–01A1). J.H.J acknowledges the support of NIH’s Microfluidics in Biomedical Sciences Training Program: NIH NIBIB T32 EB005582. S.R. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program: DGE 1256260. L.S. acknowledges support from the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship: W81XWH-10–1-0582. We would like to thank the University of Michigan School of Dentistry mCT Core, funded in part by NIH/NCRR S10RR026475–01.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- [1].a) Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA, Nat Biotechnol 2005, 23, 47; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee J, Cuddihy MJ, Kotov NA, Tissue Eng Pt B-Rev 2008, 14, 61; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dvir T, Timko BP, Kohane DS, Langer R, Nat Nanotechnol 2011, 6, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Jakus AE, Rutz AL, Jordan SW, Kannan A, Mitchell SM, Yun C, Koube KD, Yoo SC, Whiteley HE, Richter CP, Galiano RD, Hsu WK, Stock SR, Hsu EL, Shah RN, Science translational medicine 2016, 8, 358ra127; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gladman AS, Matsumoto EA, Nuzzo RG, Mahadevan L, Lewis JA, Nature materials 2016, 15, 413; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kang HW, Lee SJ, Ko IK, Kengla C, Yoo JJ, Atala A, Nat Biotechnol 2016, 34, 312; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhang Y, Zhang F, Yan Z, Ma Q, Li X, Huang Y, J. A. Rogers, 2017, 2, 17019. [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Reneker DH, Chun I, Nanotechnology 1996, 7, 216; [Google Scholar]; b) Greiner A, Wendorff JH, Angew Chem Int Edit 2007, 46, 5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Reneker DH, Yarin AL, Fong H, Koombhongse S, J Appl Phys 2000, 87, 4531. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Carnell LS, Siochi EJ, Holloway NM, Stephens RM, Rhim C, Niklason LE, Clark RL, Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5345 ; [Google Scholar]; b) Theron A, Zussman E, Yarin AL, Nanotechnology 2001, 12, 384. [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Lee J, Lee SY, Jang J, Jeong YH, Cho DW, Langmuir 2013, 28, 7267; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Deitzel JM, Kleinmeyer JD, Hirvonen JK, Tan NCB, Polymer 2001, 42, 8163 [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Zhang D, Chang J, Advanced Materials 2007, 19, 3664 ; [Google Scholar]; b) Li D, Ouyang G, McCann JT, Xia Y, Nano Letters 2005, 5, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li D, Wang YL, Xia YN, Advanced Materials 2004, 16, 361. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brown TD, Dalton PD, Hutmacher DW, Advanced Materials 2011, 23, 5651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moroni L, de Wijn JR, van Blitterswijk CA, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Signori F, Coltelli MB, Bronco S, Polym Degrad Stabil 2009, 94, 74; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou HJ, Green TB, Joo YL, Polymer 2006, 47, 7497. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Frokjaer S, Otzen DE, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005, 4, 298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Jayasinghe SN, The Analyst 2013, 138, 2215; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Townsend-Nicholson A, Jayasinghe SN, Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 3364; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jayasinghe SN, Advanced Biosystems 2017, 1, 1700067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Bitzer T, Honeycomb technology : materials, design, manufacturing, applications and testing, Chapman & Hall, London ; New York: 1997; [Google Scholar]; b) Wang AJ, McDowell DL, J Eng Mater-T Asme 2004, 126, 137. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Viswanadam G, Chase GG, Polymer 2013, 54, 1397. [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Collins G, Federici J, Imura Y, Catalani LH, J Appl Phys 2012, 111; [Google Scholar]; b) Riboux G, Marin AG, Loscertales IG, Barrero A, J Fluid Mech 2011, 671, 226. [Google Scholar]

- [17].McShane GJ, Deshpande VS, Fleck NA, J Appl Mech-T Asme 2007, 74, 658. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA, Nat Med 2008, 14, 213; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Grayson WL, Frohlich M, Yeager K, Bhumiratana S, Chan ME, Cannizzaro C, Wan LQ, Liu XS, Guo XE, Vunjak-Novakovic G, P Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107, 3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Yoshimoto H, Shin YM, Terai H, Vacanti JP, Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2077; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Billiet T, Vandenhaute M, Schelfhout J, Van Vlierberghe S, Dubruel P, Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS, Biotechnol Bioeng 2009, 103, 655; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Griffith LG, Swartz MA, Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2006, 7, 211; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stevens MM, George JH, Science 2005, 310, 1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ma JL, Both SK, Yang F, Cui FZ, Pan JL, Meijer G, Jansen JA, van den Beucken JJJP, Stem Cell Transl Med 2014, 3, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Lee JB, Jeong SI, Bae MS, Yang DH, Heo DN, Kim CH, Alsberg E, Kwon IK, Tissue Eng Pt A 2011, 17, 2695; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG, Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sun HL, Feng K, Hu J, Soker S, Atala A, Ma PX, Biomaterials 2010, 31, 1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ogawa R, Mizuno H, Watanabe A, Migita M, Shimada T, Hyakusoku H, Biochem Bioph Res Co 2004, 313, 871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sun HL, Jung YH, Shiozawa Y, Taichman RS, Krebsbach PH, Tissue Eng Pt A 2012, 18, 2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nishida K, Yamato M, Hayashida Y, Watanabe K, Yamamoto K, Adachi E, Nagai S, Kikuchi A, Maeda N, Watanabe H, Okano T, Tano Y, New Engl J Med 2004, 351, 1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Mehta G, Hsiao AY, Ingram M, Luker GD, Takayama S, J Control Release 2012, 164, 192; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Thibaudeau L, Taubenberger AV, Holzapfel BM, Quent VM, Fuehrmann T, Hesami P, Brown TD, Dalton PD, Power CA, Hollier BG, Hutmacher DW, Dis Model Mech 2014, 7, 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Stacer AC, Wang H, Fenner J, Dosch JS, Salomonnson A, Luker KE, Luker GD, Rehemtulla A, Ross BD, Molecular imaging 2015, 14, 414; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cavnar SP, Rickelmann AD, Meguiar KF, Xiao A, Dosch J, Leung BM, Cai Lesher-Perez S, Chitta S, Luker KE, Takayama S, Luker GD, Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 2015, 17, 625; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Smith MCP, Luker KE, Garbow JR, Prior JL, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, Luker GD, Cancer Research 2004, 64, 8604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.