Significance

Nearly all outer-membrane proteins (OMPs) in Gram-negative bacteria are inserted via the -barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex. Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed a persistent C-terminal strand kink of the core BAM component, BamA, which permits BamA to open laterally to the membrane. Experiments show that inhibiting kinking makes bacteria more susceptible to antibiotics. Kink-induced lateral gating may catalyze OMP insertion through a local disruption of the membrane, a pathway into the membrane, or both.

Keywords: BamA, outer membrane, β-barrels, membrane protein insertion, molecular dynamics

Abstract

In Gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane contains primarily -barrel transmembrane proteins and lipoproteins. The insertion and assembly of -barrel outer-membrane proteins (OMPs) is mediated by the -barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex, the core component of which is the 16-stranded transmembrane -barrel BamA. Recent studies have indicated a possible role played by the seam between the first and last -barrel strands of BamA in the OMP insertion process through lateral gating and a destabilized membrane region. In this study, we have determined the stability and dynamics of the lateral gate through over 12.5 s of equilibrium simulations and 4 s of free-energy calculations. From the equilibrium simulations, we have identified a persistent kink in the C-terminal strand and observed spontaneous lateral-gate separation in a mimic of the native bacterial outer membrane. Free-energy calculations of lateral gate opening revealed a significantly lower barrier to opening in the C-terminal kinked conformation; mutagenesis experiments confirm the relevance of C-terminal kinking to BamA structure and function.

The folding and membrane insertion of -barrel proteins is a process taking place in most cells, foremost among them, Gram-negative bacteria. These bacteria possess an outer membrane (OM) in addition to the more common cytoplasmic, inner membrane (IM). In contrast to the IM, the OM consists of a phospholipid inner leaflet and a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) outer leaflet and is populated almost exclusively with -barrel proteins (1–3). Likely because of their bacterial origins, mitochondria and chloroplasts also possess two membranes with -barrel proteins in their OMs (4). Outer-membrane proteins (OMPs) regulate traffic into and out of Gram-negative bacteria including water, ions, nutrients, and virulence factors in pathogenic bacteria; thus, they are critically important for bacterial survival (5–8). Their surface exposure also makes them attractive antibiotic and vaccine targets, negating the need to breach one or both membranes. OMPs are synthesized in the cytoplasm, transported across the IM by the Sec translocon, and finally cross the periplasm with assistance from several chaperones (9–12), before being assembled and inserted into the OM by the -barrel assembly machinery (BAM) (13–20).

The BAM complex is comprised of five proteins (BamA–BamE) whose structures have all been solved both individually and in complex (21–24). The most essential component of the BAM complex is BamA, which has a C-terminal 16-stranded -barrel domain as well as five N-terminal polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) domains on the periplasmic side. Early structures and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of BamA revealed three notable features (25). First, in the Neisseria gonorrhoeae BamA structure, the interaction between the first (1) and last (16) strands of the BamA -barrel is unexpectedly weak (Fig. 1). Second, equilibrium MD simulations indicated that a separation between the -strands at the barrel seam could occur, producing a so-called “lateral gate” between the hydrophobic membrane environment and the aqueous -barrel lumen. Recently, this lateral gate was also shown to exist in TamA, which is believed to have arisen via gene duplication of BamA and assists in the assembly of some OMP substrates (e.g., autotransporters like EhaA and Ag43) (26–28). Third, a thin hydrophobic region in BamA near the lateral gate produced a destabilized membrane, which may decrease the barrier for OMP integration (29–31). Together, these features have pinpointed the BamA barrel seam as the putative insertion point for nascent OMPs.

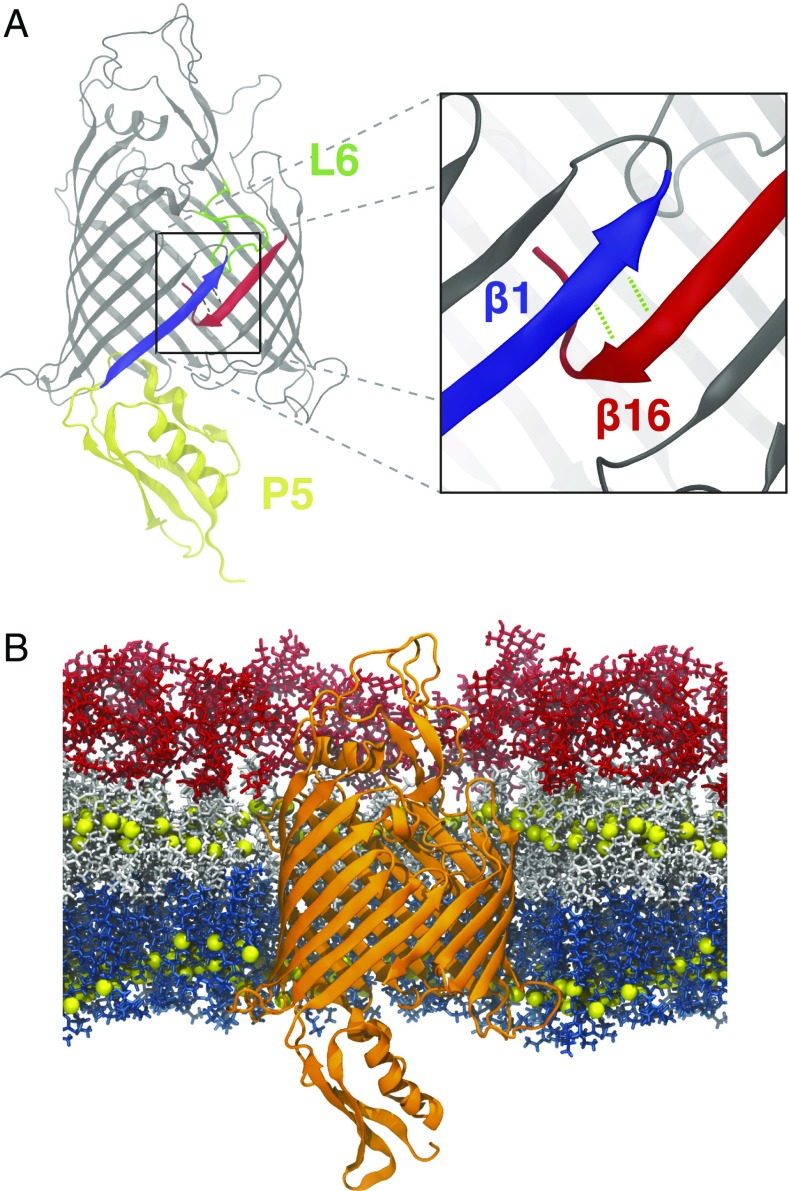

Fig. 1.

Features of BamA highlighted. (A) First (1) and last (16) -strands, which form the lateral gate, shown in blue and red, respectively. 16 is shown in the kinked conformation. -barrel and P5 domain of BamA with 1 (blue), 16 (red), P5 (yellow), and L6 (green) domains highlighted. (B) EcBamA in OM system (NgBamA in OM is not shown) used for equilibrium simulations. Protein is shown as orange ribbons; C2 (and C4 for LPS) atoms that delineate the hydrophobic region are shown as yellow spheres; phospholipids are shown as blue sticks; and lipid A and core oligosaccharide regions of LPS are shown in white and red, respectively.

The BamA 16 seam has become the centerpiece for several models for OMP assembly including the so-called “hybrid barrel model” (32, 33) and the “passive model” (34). In the passive model, the principal role played by the seam is to prime the membrane for OMP insertion. In the hybrid barrel model, the seam functions as a gate for substrate passage and/or as a template onto which nascent -barrels may assemble. However, little is known about the factors influencing the dynamics of the BamA seam. Now, using both long time-scale equilibrium MD simulations as well as free-energy calculations, we have determined the likelihood of lateral gating at this seam under different conditions. Our simulations reveal, in particular, an important role played by the kinked conformation of 16 in modulating gating energetics observed in some, but not all, crystal structures of BamA (25, 35, 36). This conformation significantly reduces the lateral gate-opening energetic barrier and is the only persistent C-terminal conformation observed throughout over 11 s of combined equilibrium simulations. Furthermore, we demonstrate that formation of the kink is important for BamA structure and function in mutagenesis experiments in which G807 of 16 is mutated to bulkier residues, rendering bacterial cells more susceptible to antibiotics.

Results

Equilibrium Simulations.

To explore the equilibrium dynamics of the BamA -barrel seam, we carried out simulations of two recent crystal structures from N. gonorrhoeae [NgBamA; Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 4K3B with all POTRA domains removed] (25) and Escherichia coli (EcBamA; PDB ID codes 4N75 and 4C4V with only POTRA5 retained; see Methods) (35, 36). EcBamA was simulated for over 4.2 s in a simplified version of the OM bilayer with LPS in the outer leaflet and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) in the inner leaflet; NgBamA was simulated for over 7 s in total in three different membranes—namely, POPE only, 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC) only, and OM (see Table 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). DLPC has been used in a number of the experimental studies of OMP folding in membranes (10, 37, 38), while POPE is a common membrane used in simulation studies of OMPs (39, 40). In these simulations, we observed several novel behaviors of the N- and C-terminal strands and the surrounding region, including C-terminal kink formation, lateral gate-opening, and membrane thinning. Notably, these behaviors are not specific to the membrane used, validating in part the use of other membranes experimentally and computationally.

Table 1.

A summary of equilibrium simulations performed for this study

| Label | PDB | Species | Time, ns | Membrane | Temperature, K |

| EcBamA-OM-310 | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | 4,255 | OM | 310 |

| NgBamA-OM-340 | 4K3B | N. gonorrhoeae | 3,146 | OM | 340 |

| NgBamA-POPE-310 | 4K3B | N. gonorrhoeae | 986 | POPE | 310 |

| NgBamA-DLPC-310 | 4K3B | N. gonorrhoeae | 986 | DLPC | 310 |

| NgBamA-DLPC-340 | 4K3B | N. gonorrhoeae | 2,102 | DLPC | 340 |

| EcBamA-G807V | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | 1,100 | OM | 310 |

Because PDB 4N75 lacks the fifth POTRA domain, P5 from PDB 4C4V was added to create the EcBamA system (see Methods).

C-Terminal Kink Formation.

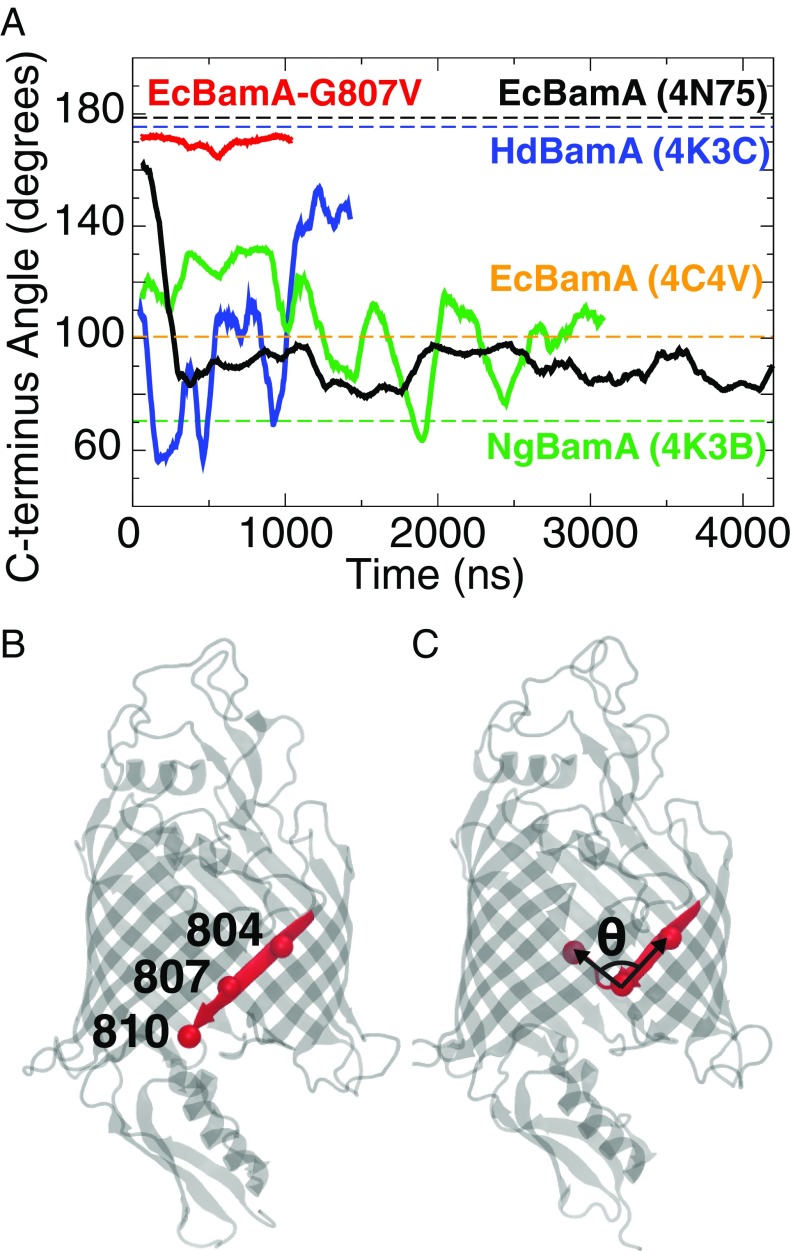

In the four available crystal structures of BamA alone (25, 35, 36), two display a C-terminal kink, in which the C-terminal -strand bends into the lumen, leaving only 2–3 hydrogen bonds at the N/C-terminal strand interface instead of 6–8 in the “zipped” conformation (see Fig. 2). To resolve the relevance of this kink, we performed a 4.2-s equilibrium simulation of EcBamA (PDB ID code 4N75), which exhibits the zipped conformation, in an OM model. After 200 ns, the C-terminal end of the 16 strand separated from the 1 strand and curled into the barrel lumen, forming the C-terminal kinked conformation seen in two of the BamA crystal structures (Fig. 2A). This conformation persists for the remainder of the simulation. In simulations of other BamA structures, kinking is either maintained (in the case of NgBamA) or forms quickly (within 20 ns in the case of HdBamA), suggesting that the kinked conformation is the more energetically favorable state of the BamA -barrel. Although HdBamA sometimes exhibits a larger angle than EcBamA and NgBamA, it does not revert to a zipped state; no more than three hydrogen bonds are maintained between the N- and C-terminal strands in any BamA (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

C-terminal kink formation in BamA. (A) Plot of the angle formed by the of residues 804, 807, and 810 throughout the simulation (E. coli numbering). These residues are shown as red spheres in cartoon renderings of the (B) zipped and (C) kinked C-terminal strand conformations. For reference, the angles formed in crystal structures are shown as dotted lines, while simulation trajectories are solid lines. Trajectories shown are EcBamA-OM-310 (black), NgBamA-OM-340 (green), HdBamA (blue), and EcBamA-G807V (red). HdBamA trajectory data are from Noinaj et al. (25). Average values for C-terminal kink angles were 92.6 for EcBamA, 103.6 for HdBamA, 106.0 for NgBamA, and 170 for G807V.

In all zipped states, W810 of BamA, a residue at the end of 16, makes contact with the membrane, whereas in kinked states it does not. Nonaromatic substitutions of W810 are lethal (41, 42) and are either not inserted to the OM at all (W810V and W810A) or are inserted at relatively low levels (W810G and W810D) (42). While an aromatic residue would be expected for a -signal, which is required for recognition and insertion and is often found at the C-terminal end of the protein (43), in BamA the -signal is located 30 residues upstream from the C terminus (44). It has been suggested that W810 is necessary for perturbing the membrane (42), suggesting that it may cycle between kinked and zipped states over much longer time scales than simulated here.

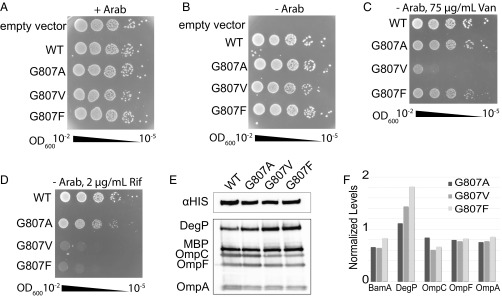

In all simulations, a glycine residue in the C-terminal strand was identified as the hinge point for kinking (Fig. 2). To test the significance of kinking, we carried out mutagenesis experiments focused on the hinge residue in EcBamA, G807. This glycine is highly conserved, being found in 83% of 2,585 BamA sequences compared and presenting as a serine or alanine in a further 9% (45). Mutation of G807 to alanine, valine, and phenylalanine did not produce abnormal growth phenotypes in our standard assays with and without arabinose (Fig. 3 A and B), just as we have observed previously (41). However, when we plated these mutants on LB–agar plates containing only the antibiotics vancomycin or rifampicin, we observed significant differences in antibiotic susceptibility for the G807V and G807F mutants. In the presence of vancomycin (75 g/mL), little to no change in susceptibility was observed for the G807A mutant, compared with WT BamA; however, changes were observed for the other mutants, with the most substantial being G807V (Fig. 3C). In the presence of rifampicin (2 g/mL), susceptibility was observed for all of the mutants, with the most extensive being both the G807V and G807F mutants (Fig. 3D). Expression levels of BamA and other OMPs show a modest but consistent drop by 20–30% for all of the mutants (Fig. 3 E and F); conversely, DegP expression is up-regulated by 10–80%, which we speculate is due to accumulation of unfolded OMPs in the periplasm. To determine if mutations of this type alter kink formation, we made the G807V mutation in silico and observed a persistent zipped conformation over 1 s (Fig. 2A). Together, these results indicate that flexibility along the kink of the C-terminal strand is important for the function of BamA.

Fig. 3.

Plate growth assays with EcBamA G807 mutants. (A and B) Wild-type EcBamA, empty pRSF-1b vector, and the G807 mutants were transformed into JCM-166 cells and serial diluted ( to ) onto LB–agar plates (A) with and (B) without arabinose. (C and D) The wild-type and G807 mutants were investigated further by plating them in the absence of arabinose but in the presence of either (C) vancomycin (75 g/mL) or (D) rifampicin (2 g/mL). (E and F) Expression levels of mutant constructs, scaled according to the MBP loading control and normalized to WT BamA. Representative experiments are shown from assays performed in triplicate.

Development of Membrane Defects.

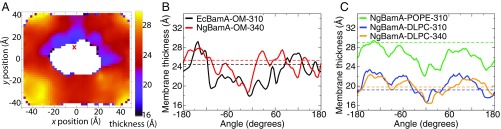

Thanks in part to the C-terminal kink, the hydrophobic thickness of the BamA barrel is especially low on the N/C-terminal side (as much as 11 Å thinner; see SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Previous MD simulations of the NgBamA structure showed that this decreased hydrophobic thickness results in a destabilized membrane region (25), which has been proposed to play a role in priming the membrane for OMP insertion (25, 32, 46). We also observe membrane thinning near the BamA seam in all simulations performed here, including that of EcBamA in the OM model (Fig. 4). The largest decrease in thickness compared with the average (7.0 Å) is demonstrated by NgBamA-POPE-310, with both OM systems being just slightly less (6.6 Å). The smallest decrease is seen in the DLPC membranes (2.6 Å for NgBamA-DLPC-310 and 3.2 Å for NgBamA-DLPC-340), which are already very thin on average (20 Å). While the thinning is most consistent and pronounced near the seam, there is also some membrane thinning in other areas, which may be helpful for insertion of large OMPs.

Fig. 4.

Membrane thinning near the N/C-terminal seam. (A) Average membrane hydrophobic thickness around EcBamA over 4.2 s of simulation in an asymmetric OM model. The red “X” marks the location of the EcBamA seam. See SI Appendix, Fig. S4 for additional systems. (B and C) Average membrane thickness within 10 Å of BamA as a function of angle for all five systems. The average angle of the 1 backbone center-of-mass has been set as the zero point. Each system exhibits a dip in membrane thickness near the seam (). The average thickness of each membrane is shown for each system as a dotted line.

Opening of a Lateral Gate at the N/C-Terminal Seam.

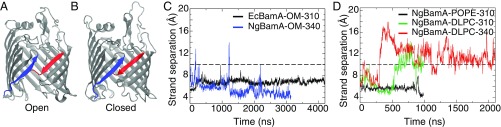

One of the most unexpected observations in previous BamA simulations is the opening of a lateral gate (25, 41). Previous equilibrium simulations on the s time scale displayed spontaneous, repeated separation and closure of the N- and C-terminal strands, albeit in a symmetric DMPE membrane. For comparison, we have examined lateral-gate formation in a variety of membrane environments including an OM model. In our simulations, strand separation was observed for NgBamA in DLPC at 310K and at 340K but not in POPE at 310K (Fig. 5D). We also performed 3.1 s of equilibrium simulation of NgBamA in an OM model at 340K. At a few points in this simulation, we observed transient separation of the N- and C-terminal strands, despite the stiffness of the OM (39) (Fig. 5). However, the simulation was performed at a higher than physiological temperature (340K), which could be partially responsible for lateral gate opening on the stated time scale. We did not observe gating for EcBamA in the OM model for over 4.2 s of simulation at 310K, although the strand separation value was dynamic, nearly crossing the 10-Å threshold at one instance (around 1 s). It also maintains a lower number of hydrogen bonds than the crystal structure (3 vs. 8; see SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Fig. 5.

(A and B) Snapshots of the (A) maximum strand separation in NgBamA-OM-340 to illustrate the open conformation (around 200 ns) and (B) a low level of strand separation to illustrate the closed conformation (around 550 ns). (C) Strand separation vs. time for BamA in an OM model. Lateral-gate strand separation occurs for NgBamA near 200 ns and again around 1,200 ns. (D) Strand separation versus time for NgBamA in symmetric bilayer systems. Lateral-gate separation was observed for DLPC bilayer simulations at 340K (red) and 310K (green) but not for POPE at 310K (black).

PMF Calculations.

To further investigate the factors influencing the stability of the N/C-terminal seam of BamA, we used the replica-exchange umbrella sampling (REUS) technique to calculate the potential of mean force (PMF) for lateral gate opening. BamA from two species, E. coli and N. gonorrhoeae, as well as FhaC, a homolog with a different function from B. pertussis (47), were modified to produce a total of 10 unique systems (see Table 2). A POPE bilayer was used instead of the stiffer OM (39) to focus on differences between proteins. Most of the systems are discussed in SI Appendix, with the focus below on those that were run in both the kinked and zipped conformations.

Table 2.

Summary of free-energy calculations performed for this study

| Label | PDB | Species | Modification | Start conformation |

| EcBamA-WT-z | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | Wild type | Zipped |

| EcBamA-FG-z | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | FhaC gate | Zipped |

| FhaC-WT-z | 4QKY | Bordetella pertussis | Wild type | Zipped |

| FhaC-BG-z | 4QKY | B. pertussis | EcBamA gate | Zipped |

| EcBamA-P5-z | 4N75 | E. coli | P5 deletion | Zipped |

| EcBamA-L6-z | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | L6 deletion | Zipped |

| EcBamA-WT-k | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | Wild type | Kinked |

| EcBamA-P5-k | 4N75 | E. coli | P5 deletion | Kinked |

| EcBamA-L6-k | 4N75, 4C4V | E. coli | L6 deletion | Kinked |

| NgBamA-P5-k | 4K3B | N. gonorrhoeae | P5 deletion | Kinked |

The labels are given as (protein)–(modification) – (C-terminal strand conformation). For the modification label, WT stands for wild type, and “FG” and “BG” stand for FhaC-gate and EcBamA-gate replacement, respectively. “ΔP5” and “ΔL6” stand for deletion of P5 and L6, respectively. The final element of the label, which is either a “z” or a “k,” indicates whether the C-terminal strand started in the zipped or kinked conformation, respectively. Unless otherwise indicated, all systems contain a single POTRA domain (P5 for BamA and P2 for FhaC).

Energetics of Gate Opening for EcBamA and FhaC.

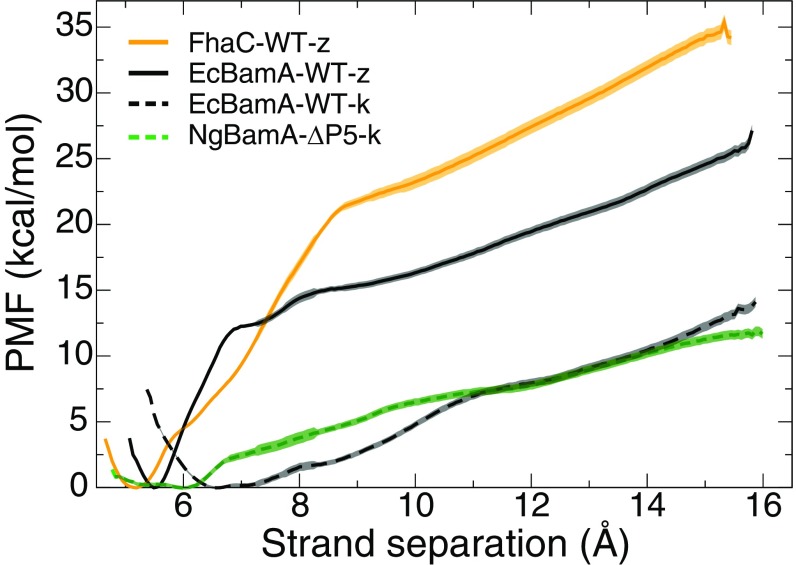

As a first step in addressing the energetic landscape of lateral gate opening, we calculated the PMF versus strand separation for BamA from E. coli (PDB ID code 4N75) (25) as well as for FhaC from B. pertussis (PDB ID code 4QKY) (47). FhaC was chosen as a control system since it is a member of the same protein family (Omp85), contains many structural similarities, and was previously demonstrated to possess a stable 16 interface (25). Calculated PMFs for EcBamA-WT-z and FhaC-WT-z (nomenclature detailed in Table 2) are shown in Fig. 6. The PMF of lateral gate opening for EcBamA was found to be significantly lower (by 5–10 kcal/mol) than that of FhaC at equivalent degrees of separation.

Fig. 6.

PMFs for lateral gate opening at the N/C-terminal seam. PMFs for all BamA variants are lower than that for FhaC. PMFs for kinked starting states (dashed lines) are lower than those for zipped starting states (solid lines). The shading indicates 1 SD, which demonstrates that the differences between kinked and zipped PMFs are significant. See SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7 for additional PMFs and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 for convergence and statistical error.

C-Terminal Kink Formation Reduces Gate-Opening Energy.

One of the major differences between the EcBamA and NgBamA crystal structures is that in NgBamA, the C-terminal strand already possesses a kinked conformation where the 16 connection is weaker, with only two hydrogen bonds holding the strands together (25). To assess the role of C-terminal kinking on lateral gate-opening energy, we calculated the PMF of lateral gate opening starting from the kinked NgBamA structure. This calculation yielded significantly lower PMF values with a relatively flat profile around the closed state (Fig. 6). However, the energy difference between kinked NgBamA and zipped EcBamA is 10 to 15 kcal/mol, which is within the expected range, considering an additional 6 to 8 hydrogen bonds must be broken in the zipped EcBamA lateral gate, each with 1.6 kcal/mol per hydrogen bond (48) (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10). We recently calculated the gate-opening PMF for TamA (28), which also has a kinked C-terminal strand; we found similarly low PMF values compared with NgBamA (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

To better understand the role that kink formation plays in lateral gate-opening energetics, we repeated the EcBamA PMF calculation for a modified starting state in which the C-terminal strand was already kinked. We observed a significant decrease in PMF values, as expected from the NgBamA and TamA PMFs. However, the kinked EcBamA PMF also displays a deeper energetic well than that of NgBamA with a minimum shifted by about 1.0 Å with respect to the zipped EcBamA PMF (Fig. 6).

To determine the role of the -barrel beyond the N/C-terminal strands, we calculated the average slope of the PMFs from 10 Å to 15 Å (SI Appendix, Fig. S11)—that is, beyond where the barrel-seam strands interact. FhaC variants presented the highest slopes at 2.2 kcal/molÅ, whereas BamA presents a range of 1–2 kcal/molÅ, suggesting that not only is the seam of BamA adapted for opening but possibly its entire -barrel as well. The lowest slopes were consistently found for BamA constructs missing P5 (1 kcal/molÅ). P5 interacts with a varying number of periplasmic loops depending on its position, and thus, it may serve as a switch to modulate BamA’s ability to open laterally.

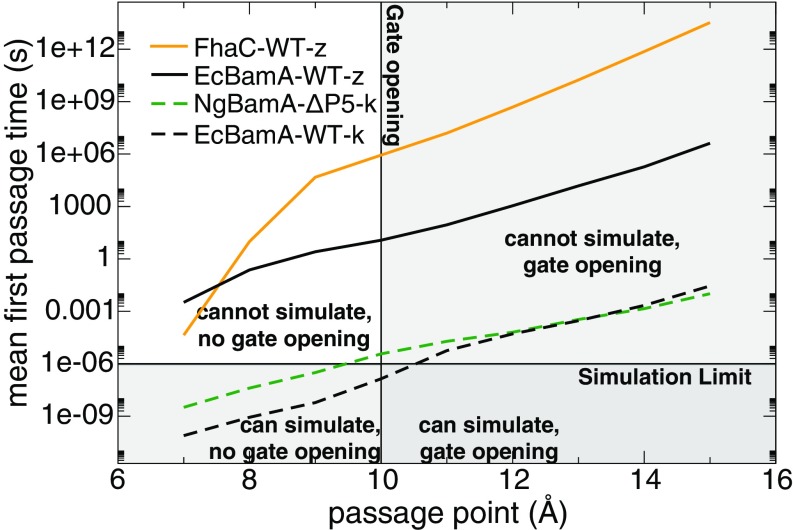

To reconcile the PMF calculations with observations in equilibrium simulations, we determined the mean first passage time (MFPT) of four systems as a function of gate-opening distance (Fig. 7). For both zipped states (EcBamA-WT-z and FhaC-WT-z), the MFPTs at openings even as low as 7 Å are beyond the accessible simulation time scale. For the kinked states (EcBamA-WT-k and NgBamA-P5-k), on the other hand, the MFPT predicts that openings above the empirical gate-opening cutoff (10 Å) are possible on the microsecond time scale, as was observed in some of our equilibrium simulations. While we did not observe gate opening for NgBamA-P5-k in a POPE bilayer in 1 s, this simulation time is just under the MFPT for this system; we expect a simulation 5–10× longer would display transient opening.

Fig. 7.

Calculated MFPTs as a function of gate-opening distance (49).

Discussion

To address the role of the lateral gate in BamA function, we performed a series of equilibrium MD simulations in several membrane environments including an approximation of the E. coli OM, a POPE bilayer, and a DLPC bilayer. We also performed a calculation of the energetic landscape associated with the opening of the lateral gate. In our equilibrium simulations, we observed the transition of the C-terminal strand from a zipped to a kinked conformation but never the reverse transition. In over 11 s of simulation, we never observed the presence of a stable zipped conformation, casting doubt on its physiological relevance. Mutagenesis experiments also point to the need for a kinked C-terminal strand, as demonstrated by the increase in antibiotic susceptibility when C-terminal strand residue G807 is replaced with either alanine, valine, or phenylalanine (Fig. 3). Equilibrium simulations demonstrated that indeed the G807V mutation prevented C-terminal kink formation (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we observed opening of the NgBamA lateral gate in several systems, including in a native-like OM (albeit at 340K) and in DLPC. Finally, we observed localized membrane thinning due to a hydrophobic mismatch between the membrane and the barrel near the lateral gate. The observed thinning was most prominent for the thicker membranes (OM and POPE) and much less pronounced in the thinner DLPC. In addition to the thinning near the lateral gate, the symmetric membrane systems also demonstrated thinning on the side of the barrel opposite the lateral gate.

We calculated the energetic landscape of lateral gate opening for a total of 10 systems. For the zipped conformation, EcBamA was shown to possess a lower barrier to opening compared with a control protein (FhaC) with no suspected lateral gate. The importance of the C-terminal kink formation observed in the equilibrium simulations is echoed in the PMF results; systems that began in a kinked conformation exhibited drastically lower opening energies (10–15 kcal/mol) compared with zipped wild-type BamA (EcBamA-WT-z). In fact, the importance of the kinked state is further demonstrated by the fact that deletion of two important moieties produce opposite effects on the energy profile depending on whether or not the kink is present. In particular, deletion of loop 6 (L6) and POTRA 5 (P5) results in a decrease of opening energy with respect to zipped wild-type EcBamA but a slight increase with respect to kinked EcBamA (see SI Appendix). Any perturbation of the zipped wild-type BamA state translates to a decrease in opening energy. However, the fact that modifications to the kinked state result in an increase in energy points to the possibility that these moieties have evolved to assist BamA in maintaining its permissive lateral gate. In general, our results point to a crucial role played by the barrel seam. This role supports existing models either as a membrane insertion point and/or as a template for nascent OM proteins.

While the present results add to the body of evidence indicating that the formation of a lateral gate plays an important role in the function of BamA, a mechanism consistent with all of the present findings has yet to emerge (50). Recently, striking evidence for a hybrid barrel model was presented in a study of the mitochondrial BamA homolog Sam50 (51). There, it was found through disulfide cross-linking that -barrel precursors translocate into the Sam50 channel and then enter the lateral gate as -hairpins, interacting with both N- and C-terminal strands of Sam50 (51). Nonetheless, in another recent study, it was found that a disulfide-locked lateral gate still accelerates the insertion of an eight-strand -barrel OmpX, which runs contrary to the hybrid barrel model (34). Regardless of the exact mechanism, membrane thinning, as consistently observed in our simulations, plays a vital role in OMP insertion by significantly lowering the insertion free-energy barrier. We observed a weak correlation between membrane thinning and lateral gate strand separation, primarily for NgBamA in DLPC (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), which suggests that lateral gating may serve to induce further membrane thinning and destabilization, consistent with the passive model.

Finally, we posit that a different mode of insertion may be used depending on the size or makeup of the OMP being inserted. Low-strand number OMPs may form their barrel before insertion (52), while high-strand number OMPs, requiring more assistance from BamA directly, may insert piecewise through its lateral gate. Indeed, insertion of the 24-strand -barrel FimD is sequential, with the C terminus inserting before the N terminus (53).

Methods

Equilibrium Simulation Systems.

Four BamA systems were constructed for the purpose of study through equilibrium simulations. First, a structural model of BamA from E. coli was assembled using the -barrel domain (residues 427–810) from PDB ID code 4N75 (35) and the fifth periplasmic domain (P5) (residues 344–426) from PDB ID code 4C4V (36). Second, a model for BamA from N. gonorrhoeae was assembled using only the -barrel domain (residues 417–792) from PDB ID code 4K3B (25). Both BamA models were placed in an asymmetric OM consisting of an LPS outer leaflet and a POPE inner leaflet. In addition, two symmetric-membrane systems were constructed by placing the N. gonorrhoeae BamA model in DLPC and POPE bilayers. Construction of all systems was performed using visual molecular dynamics (VMD) (54). Total atom counts were 75–85,000. Lateral gate separation is measured as the center-of-mass distance between the 1 and 16 strands using and from residues 427 to 433 and 804 to 810 for EcBamA, 427 to 433 and 786 to 792 for NgBamA, and 212 to 218 and 548 to 554 for FhaC.

MD Protocol.

Equilibrium simulations of BamA (see Table 1) were run on the Anton 1 supercomputer at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (55). All Anton simulations used the CHARMM36 force field for both proteins (56) and lipids (57). Constant temperature (310 K or 340 K) and pressure (1 atm along the membrane normal) were maintained in the Multigrator framework (58) using a semi-isotropic Martyna–Tuckerman–Klein barostat (59) and Nosé–Hoover thermostat (60, 61). A time step of 2 fs was used with short-range nonbonded interactions updated every time step and long-range electrostatics updated every three time steps. For most simulations, the cutoff for short-range nonbonded interactions was chosen by the Anton guesser to be 11 Å, while for the EcBamA outer-membrane simulation, it was chosen to be 14.5 Å. Long-range electrostatics were calculated using the k-Gaussian Split Ewald method with a 64 64 64 mesh (62).

REUS Simulations.

A total of 10 systems were constructed for the purpose of calculating the PMF of lateral gate opening. All 10 systems were derived through modifications made to three systems constructed based on the structures of E. coli BamA and N. gonorrhoeae BamA noted above as well as that of B. pertussis FhaC (PDB ID code 4QKY). They were assembled in a POPE bilayer generated using the CHARMM-GUI membrane builder (63, 64), solvated with the VMD Solvate plugin, and ionized to 150 mM KCl using the VMD Autoionize plugin. The Orientation of Proteins in Membranes web interface (65) was used to determine the ideal membrane placement of all proteins. See SI Appendix, Methods for more details of the systems’ construction and equilibration.

The adaptive biasing force (ABF) method (66) implemented in NAMD (67) was used to generate the open states by applying the biasing force to the 1 and 16 stands flanking the lateral gate. The systems were then equilibrated for 20 ns with colvars (68) restraints maintaining the open state. Additional details of the system preparation and setup of windows for umbrella sampling are provided in SI Appendix, Methods.

All of the PMFs in this study were calculated using the REUS procedure (69, 70). The reaction coordinate used is the lateral gate separation defined above. Umbrella sampling windows were spaced 0.5 Å apart and centered at center-of-mass distance values ranging from 5.5 Å to 15.0 Å. Each of the 20 windows was confined to the center of the reaction coordinate value using a harmonic well with a force constant value of 10.0 kcal/molÅ for the first six windows and 5.0 kcal/molÅ for the remaining 14 windows. The simulation time for each system was 20 ns per window (400 ns per system). Sampling data from the REUS simulations were used to generate PMFs by using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) (71). Convergence of the PMFs and error bars are illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S8. Diffusivities needed for the MFPT calculation were determined using ACFCalculator from Gaalswyk et al. (72) (see SI Appendix).

Plate Assays.

Wild-type BamA and BamA mutants (G807A, G807V, and G807F) were each cloned into the pRSF-1b plasmid as previously described (41) and transformed into JCM-166 cells that harbor endogenous BamA under the control of an arabinose promoter (13, 25). Empty pRSF-1b plasmid was used as a negative control. Transformations were plated on LB plates containing 50 g/mL kanamycin with or without arabinose. For serial dilution assays of the constructs, single colonies from plates without arabinose were used to inoculate 5 mL LB cultures supplemented with 50 g/mL kanamycin and grown at 37 °C to an of 1.5. Cells from each culture were then pelleted and washed three times with 1× PBS, diluted to an of 0.1, and then serial diluted by a factor of 10. Diluted cultures were plated as 4 L drops onto LB–agar plates with 50 g/mL kanamycin and containing either vancomycin (75 g/mL) or rifampicin (2 g/mL). Plates were then incubated at 37 °C inverted for 12 h. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (25). Densitometry analysis was performed using GE ImageQuant TL 8.1 and the final graph prepared by scaling the samples using the maltose-binding protein (MBP) loading control and normalizing against WT BamA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hyea Hwang for assistance with BamA sequence alignments as well as Abhishek Singharoy for his careful reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-1452464 and National Institutes of Health Grant R01-GM123169 (to J.C.G.). J.B. is supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant 1F32GM121021-01A1, and N.N. is supported by the Department of Biological Sciences at Purdue University, a Showalter Trust Award, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant 1K22AI113078-01. Computational resources were provided through the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by NSF Grant OCI-1053575. Anton computer time was provided by the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC) through National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM116961. The Anton machine at PSC was generously made available by D.E. Shaw Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.O.D. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1722530115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong C, et al. Wza the translocon for E. coli capsular polysaccharides defines a new class of membrane protein. Nature. 2006;444:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slusky JS. Outer membrane protein design. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;45:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb CT, Heinz E, Lithgow T. Evolution of the -barrel assembly machinery. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:612–620. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koebnik R, Locher KP, Van Gelder P. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: Barrels in a nutshell. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:239–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noinaj N, et al. Structural basis for iron piracy by pathogenic Neisseria. Nature. 2012;483:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang JH, Tong J, Tan KS, Gabriel K. From evolution to pathogenesis: The link between -barrel assembly machineries in the outer membrane of mitochondria and gram-negative bacteria. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:8038–8050. doi: 10.3390/ijms13078038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sklar JG, Wu T, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. Defining the roles of the periplasmic chaperones SurA, Skp, and DegP in Escherichia Coli. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2473–2484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1581007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon CP, Zaccai NR, Fleming PJ, Gessmann D, Fleming KG. Membrane protein thermodynamic stability may serve as the energy sink for sorting in the periplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4285–4290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212527110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello SM, Plummer AM, Fleming PJ, Fleming KG. Dynamic periplasmic chaperone reservoir facilitates biogenesis of outer membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E4794–E4800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikdar R, Peterson JH, Anderson DE, Bernstein HD. Folding of a bacterial integral outer membrane protein is initiated in the periplasm. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1309. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu T, et al. Identification of a multicomponent complex required for outer membrane biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2005;121:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voulhoux R, Bos MP, Geurtsen J, Mols M, Tommassen J. Role of a highly conserved bacterial protein in outer membrane protein assembly. Science. 2003;299:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1078973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagan CL, Kim S, Kahne D. Reconstitution of outer membrane protein assembly from purified components. Science. 2010;328:890–892. doi: 10.1126/science.1188919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos MP, Robert V, Tommassen J. Biogenesis of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. The Bam machine: A molecular cooper. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:1067–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles TJ, Scott-Tucker A, Overduin M, Henderson IR. Membrane protein architects: The role of the BAM complex in outer membrane protein assembly. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:206–214. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagan CL, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. -Barrel membrane protein assembly by the Bam complex. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:189–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061408-144611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rollauer SE, Sooreshjani MA, Noinaj N, Buchanan SK. Outer membrane protein biogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20150023. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakelar J, Buchanan SK, Noinaj N. The structure of the -barrel assembly machinery complex. Science. 2016;351:180–186. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Y, et al. Structural basis of outer membrane protein insertion by the BAM complex. Nature. 2016;531:64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature17199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han L, et al. Structure of the BAM complex and its implications for biogenesis of outer-membrane proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:192–196. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iadanza MG, et al. Lateral opening in the intact -barrel assembly machinery captured by cryo-EM. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12865. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noinaj N, et al. Structural insight into the biogenesis of -barrel membrane proteins. Nature. 2013;501:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nature12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selkrig J, et al. Discovery of an archetypal protein transport system in bacterial outer membranes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinz E, Selkrig J, Belousoff MJ, Lithgow T. Evolution of the translocation and assembly module (TAM) Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:1628–1643. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bamert RS, et al. Structural basis for substrate selection by the translocation and assembly module of the -barrel assembly machinery. Mol Microbiol. 2017;106:142–156. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh D, Shanmugavadivu B, Kleinschmidt JH. Membrane elastic fluctuations and the insertion and tilt of beta-barrel proteins. Biophys J. 2006;91:227–232. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pocanschi CL, Patel GJ, Marsh D, Kleinschmidt JH. Curvature elasticity and refolding of OmpA in large unilamellar vesicles. Biophys J. 2006;91:L75–L77. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danoff EJ, Fleming KG. Membrane defects accelerate outer membrane -barrel protein folding. Biochemistry. 2015;54:97–99. doi: 10.1021/bi501443p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Berg B. Lateral gates: -barrels get in on the act. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1237–1239. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim KH, Aulakh S, Paetzel M. The bacterial outer membrane -barrel assembly machinery. Protein Sci. 2012;21:751–768. doi: 10.1002/pro.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doerner PA, Sousa MC. Extreme dynamics in the BamA -barrel Seam. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3142–3149. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ni D, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the -barrel domain of BamA from Escherichia coli. FASEB J. 2014;28:2677–2685. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-248450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albrecht R, et al. Structure of BamA, an essential factor in outer membrane protein biogenesis. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70:1779–1789. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714007482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleinschmidt JH, Tamm LK. Secondary and tertiary structure formation of the beta-barrel membrane protein OmpA is synchronized and depends on membrane thickness. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burgess NK, Dao TP, Stanley AM, Fleming KG. Beta-barrel proteins that reside in the Escherichia coli outer membrane in vivo demonstrate varied folding behavior in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26748–26758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802754200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balusek C, Gumbart JC. Role of the native outer-membrane environment on the transporter BtuB. Biophys J. 2016;111:1409–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlova A, Hwang H, Lundquist K, Balusek C, Gumbart JC. Living on the edge: Simulations of bacterial outer-membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1858:1753–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noinaj N, Kuszak AJ, Balusek C, Gumbart JC, Buchanan SK. Lateral opening and exit pore formation are required for BamA function. Structure. 2014;22:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu Y, Zeng Y, Wang Z, Dong C. BamA 16C strand and periplasmic turns are critical for outer membrane protein insertion and assembly. Biochem J. 2017;474:3951–3961. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robert V, et al. Assembly factor Omp85 recognizes its outer membrane protein substrates by a species-specific C-terminal motif. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hagan CL, Wzorek JS, Kahne D. Inhibition of the β-barrel assembly machine by a peptide that binds BamD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415955112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heinz E, Lithgow T. A comprehensive analysis of the Omp85/TpsB protein superfamily structural diversity, taxonomic occurrence, and evolution. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:370. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gessmann D, et al. Outer membrane -barrel protein folding is physically controlled by periplasmic lipid head groups and BamA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5878–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322473111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maier T, et al. Conserved Omp85 lid-lock structure and substrate recognition in FhaC. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7452. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheu SY, Yang DY, Selzle HL, Schlag EW. Energetics of hydrogen bonds in peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12683–12687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133366100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szabo A, Schulten K, Schulten Z. First passage time approach to diffusion controlled reactions. J Chem Phys. 1980;72:4350–4357. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noinaj N, Gumbart JC, Buchanan SK. The -barrel assembly machinery in motion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:197–204. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Höhr AIC, et al. Membrane protein insertion through a mitochondrial -barrel gate. Science. 2018;359:eaah6834. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleinschmidt JH, Bulieris PV, Qu J, Dogterom M, den Blaauwen T. Association of neighboring -strands of outer membrane protein A in lipid bilayers revealed by site-directed fluorescence quenching. J Mol Biol. 2011;407:316–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stubenrauch C, et al. Effective assembly of fimbriae in Escherichia coli depends on the translocation assembly module nanomachine. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16064. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw DE, et al. SC’09: Proceedings of the Conference on High Performance Computing Networking, Storage and Analysis. ACM; New York: 2009. Millisecond-scale molecular dynamics simulations on Anton; pp. 39:1–39:11. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Best RB, et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone , and side-chain and dihedral angles. J Chem Theor Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klauda JB, et al. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: Validation on six lipid types. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lippert RA, et al. Accurate and efficient integration for molecular dynamics simulations at constant temperature and pressure. J Chem Phys. 2013;139:164106. doi: 10.1063/1.4825247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martyna GJ, Tobias DJ, Klein ML. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J Chem Phys. 1994;101:4177–4189. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoover WG. Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys Rev A. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martyna GJ, Klein ML, Tuckerman M. Nosé-Hoover chains—The canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J Chem Phys. 1992;97:2635–2643. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shan Y, Klepeis JL, Eastwood MP, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Gaussian split Ewald: A fast Ewald mesh method for molecular simulation. J Chem Phys. 2005;122:54101. doi: 10.1063/1.1839571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu EL, et al. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J Comput Chem. 2014;35:1997–2004. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lomize MA, Pogozheva ID, Joo H, Mosberg HI, Lomize AL. OPM database and PPM web server: Resources for positioning of proteins in membranes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D370–D376. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Darve E, Rodriguez-Gomez D, Pohorille A. Adaptive biasing force method for scalar and vector free energy calculations. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:144120. doi: 10.1063/1.2829861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fiorin G, Klein ML, Hénin J. Using collective variables to drive molecular dynamics simulations. Mol Phys. 2013;111:3345–3362. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sugita Y, Kitao A, Okamoto Y. Multidimensional replica-exchange method for free-energy calculations. J Chem Phys. 2000;113:6042–6051. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculation on biomolecules. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gaalswyk K, Awoonor-Williams E, Rowley CN. Generalized Langevin methods for calculating transmembrane diffusivity. J Chem Theor Comput. 2016;12:5609–5619. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.