Abstract

Micro-electron diffraction, or MicroED, is a structure determination method that uses a cryo-transmission electron microscope to collect electron diffraction data from nanocrystals. This technique has been successfully used to determine the high-resolution structures of many targets from crystals orders of magnitude smaller than what is needed for X-ray diffraction experiments. In this review, we will describe the MicroED method and recent structures that have been determined. Additionally, applications of electron diffraction to the fields of small molecule crystallography and materials science will be discussed.

Introduction to MicroED

Crystallographic methods have been the most widely used in structural biology for the determination of high-resolution biomolecular structures. While X-ray crystallography has been extremely successful by all measures, with over 120 000 structures in the protein data bank determined by this method, it relies on the formation of large well-ordered crystals, which, for difficult targets or when samples are limiting (e.g. membrane proteins, [1]), can be an insurmountable barrier to structure determination. Because of this, there has been a drive to develop new methods and equipment to determine high-resolution structures from crystals that are many orders of magnitude smaller than what has been conventionally used. For example, X-ray free electron lasers (XFELs) have been employed to determine protein structures from microcrystals [2–5]; however, there are some issues related to the quantity of material needed and XFEL accessibility, with beam time being scarce and costly. Micro-electron diffraction (MicroED) is a cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) technique that is capable of determining atomic resolution structures from nanocrystals only a few protein layers thick [6–9]. Because electrons have a much stronger interaction with matter and are less damaging per scattering event [10] when compared with X-rays, electron diffraction is capable of producing high-quality diffraction data from crystals a billion times smaller than what is necessary for X-ray diffraction. Additionally, the cost of a cryo-TEM (cryo-transmission electron microscope) to perform MicroED is in the range of a few million dollars, while the cost of an XFEL is over a billion dollars. In this review, we describe the MicroED technique as it is currently used, as well as the application of electron diffraction to biological samples, small organic molecules, and novel inorganic materials.

MicroED sample requirements

Ideal samples for electron diffraction are well-ordered crystals less than 500 nm in thickness [11,12]. The strong interactions of electrons with the sample allow data collection from very small crystals; however, it also means that if the samples become too thick, all signals will be lost to the absorption. Nanocrystals suitable for MicroED can grow directly out of sparse matrix screens using only ~0.1 μl of the sample per condition. Many of the conditions yield preparations that are not suitable for X-ray crystallography, but that actually contain useful nanocrystals for MicroED [13–15]. Such drops may appear as milky or granular aggregates. Once identified, either by UV fluorescence, second-order non-linear imaging of chiral crystals, or by negative-stain EM [14–16], nanocrystals can then be directly used to determine high-resolution structures if they are well-ordered. The second approach for generating samples for MicroED is to fragment larger disordered protein crystals. Because fragmentation releases individual crystal domains, each domain may be well ordered and suitable for MicroED [17]. Several methods for crystal fragmentation have been used, including gentle sonication, vigorous pipetting, and vortexing with small glass or metallic beads. Fragmentation from large imperfect crystals to small nanocrystals was shown to significantly improve diffraction quality. The most extreme example was for the tau peptide whose large crystal bundles yielded very poor 8 Å diffraction by X-rays, but after fragmentation the structure was solved at 1.1 Å resolution by MicroED [17]. Both of these observations — that many previously discarded crystallization experiments actually contain small crystals, and that fragmenting larger poor-quality crystals can yield high-quality crystal domains — are very important for the field of structural biology, as it means many samples and crystallization experiments that were once abandoned may be amenable to analysis by MicroED. The use of MicroED with these kinds of samples can save time and resources as the optimization of crystals once considered poor quality can take years to improve to the levels required for X-ray crystallography.

Once crystals of a suitable size are found, MicroED samples are prepared in a manner similar to single-particle cryoEM. This process involves applying the sample directly to a holy carbon EM grid, followed by blotting and vitrification in liquid ethane [18–20]. There are several parameters that should be optimized when making MicroED samples, including crystal concentration, blotting time, and the addition of low molecular mass cryoprotectants (e.g. ethylene glycol or methyl pentadiol). Detailed protocols for MicroED sample preparation can be found in ref. [18].

Microscopes, cameras, and data collection

MicroED data collection is performed using conventional cryo-TEM instrumentation, making MicroED a widely accessible technique. Once samples are loaded into the cryo-TEM, the sample is screened for the presence of promising crystals, and diffraction quality of crystals is analyzed by collecting an initial diffraction pattern. The crystal screening process is often times the most time-consuming part in a MicroED experiment, with the identification of quality crystals taking 1–2 h, or more. To help alleviate this, the crystal screening procedure can be automated using standard cryoEM data collection programs such as SerialEM [21]. Crystals that show high-quality diffraction (Figure 1) are then used to collect a full data set. Data collection is performed using ‘continuous rotation’, which means that data are collected as a fast movie while the crystal is continuously rotating in a single direction [12,22]. This method is analogous to the rotation method in X-ray crystallography [23]. The electron beam is set to ultra-low dose (~0.01 e−/Å2/s) to minimize radiation damage and allow a full dataset to be collected from a single crystal, which typically takes ~5–10 min. A large enough wedge of reciprocal space must be sampled for data processing and typically ~20° is sufficient; however, many samples survive long enough to allow ~50 degrees of data to be collected. Detailed protocols for MicroED data collection can also be found in ref. [18]. Continuous rotation data collection produces electron diffraction data which is analogous to X-ray rotation diffraction data, and because of this, MicroED data can be processed by many common programs used for X-ray crystallography (e.g. MOSFLM [24,25], DIALS [26], and XDS [27]). Further data processing and structure refinement are performed using the standard crystallographic programs found in the CCP4 [28] and PHENIX [29] suites, using the electron scattering factors available in these programs.

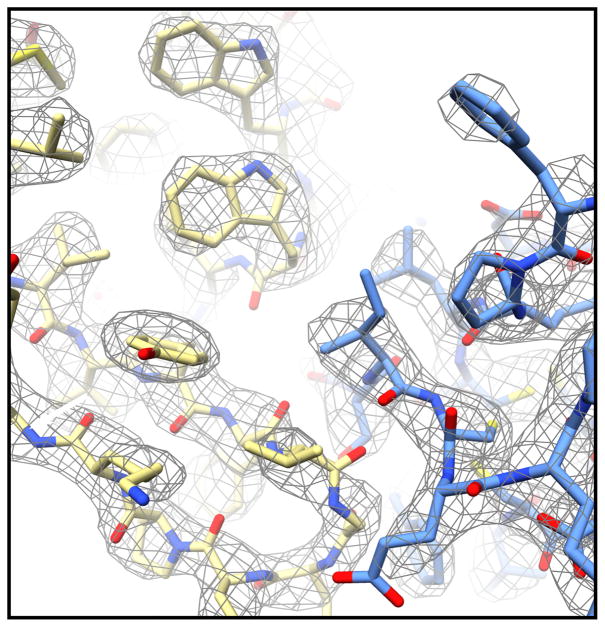

Figure 1. Example of high-quality MicroED data.

The electron diffraction pattern collected from a Proteinase K microcrystal (inset) shows sharp and well-resolved reflections that extend to high resolution. This image represents one of ~100 diffraction patterns that are part of a full data set collected from a single crystal. The scale bar in the inset represents 2 μm.

The method of continuous rotation MicroED data collection requires a cryo-TEM that is capable of low-dose operation as well as being able to perform constant continuous stage rotation. Nearly, all MicroED structures have been determined using FEI microscopes [6,12,17,30–35]; however, JEOL and Hitachi systems [36] are also capable of collecting MicroED data. Additionally, the camera used to collect diffraction data must be able to operate at frame rates fast enough to collect data as the stage is continuously rotated. Many high-speed CMOS detectors (TVIPS F416 [18,22] and XF416, Gatan OneView, upgraded FEI CETA) and hybrid pixel array detectors (e.g. Timepix, [37,38]) are capable of recording data with minimal readout times, thereby limiting gaps in continuous rotation data collection. Direct electron detectors (Gatan K2 and K3, FEI Falcon detectors, and Direct Electron cameras) can be used to collect diffraction data at a high rate; however, there are not currently any published MicroED structures making use of these detectors as the data from CMOS detectors are already of extremely high quality. CCD sensors are not recommended for MicroED data collection due to their relatively slow read out speed and their susceptibility to blooming effects [39]; however, it is important to note that the structures of Ca2+-ATPase and catalase were successfully determined using a high-quality CCD camera (TVIPS F224HD) [40].

MicroED for biological macromolecules

In the four years since the proof-of-principle work and the establishment of MicroED [34], the method has been continually developed to greatly improve and streamline the way the data are collected and analyzed [18,30]. The improvements to resolution can be seen by examining the initial MicroED lysozyme structures determined in 2013 and 2014 (2.9 Å [34] and 2.5 Å [12], respectively), and comparing them with the recent lysozyme structure released in 2017 that was determined to be 1.5 Å [17]. All three of these lysozyme structures were determined using data collected with the same microscope with same camera and microcrystals grown using the same conditions; however, improvements to data collection and processing methods have greatly improved the resulting final structures. In addition to improvements in resolution and data quality, MicroED has been adapted and improved to analyze a variety of biological macromolecules. Since late 2013, there have been 21 total structures determined by MicroED, with over a third of them being released thus far in 2017 [9]. One particular example, bovine liver catalase, was determined by MicroED to be 3.2 Å in 2014 using microcrystals similar to those that had been initially discovered several decades earlier [32], which are only ~6–10 layers thick. Despite being first identified by Sumner and Dounce in 1937 [41], and analyzed for many years by electron microscopy [42–46], these microcrystals had resisted structure determination in an electron microscope until MicroED was employed with the cryogenic sample preparation and fast detectors that facilitated continuous rotation data collection.

MicroED has been extremely successful at determining the atomic structures of amyloid assemblies. All of the amyloidogenic peptides studied by MicroED only form crystals that are extremely small and not conducive to any other form of structure determination. The 11-residue core of α-synuclein was determined to be 1.4 Å in 2015 and was the first novel structure of an oligopeptide determined by MicroED [47]. Since this initial structure was released, several other peptides from amyloid proteins have been determined and have provided critical information about the potential mechanism of amyloid-related diseases [9,17,31,33,47]. In addition to the biological importance of these samples, they have also been found to be an ideal method development sample for MicroED. One study used ab initio structure determination to solve the structure of Sup35 fragments (Figure 2) [33]. Not only was this the first time a MicroED structure had been determined by direct phasing methods, it showed that the intensities obtained by electron diffraction are very accurate and are not excessively affected by dynamical diffraction, which further confirmed findings from previous studies [11,12,32]. The effect of dynamical scattering in MicroED was probed more deeply recently [10], indicating that dynamical scattering does not inhibit structure determination even from crystals as thick as ~500 nm.

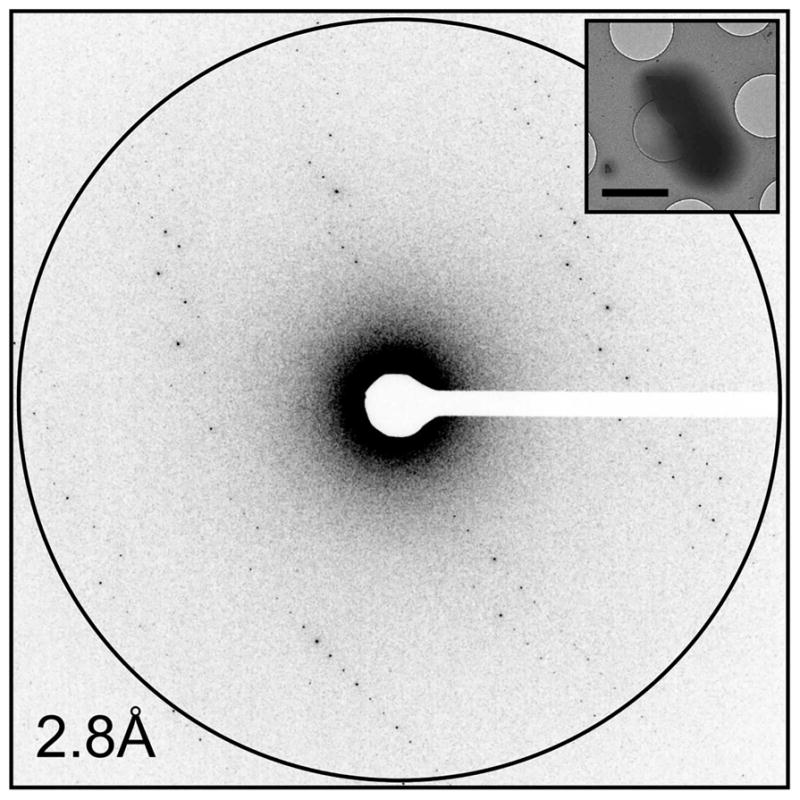

Figure 2. MicroED structure of a yeast prion Sup35 fragment phased by direct methods.

MicroED data were collected from six crystals to 1.0 Å, which was sufficient for ab initio structure determination of the NNQQNY peptide. A zinc atom (gray sphere) and acetate molecule (far right), as well as several water molecules (red spheres), can also be resolved along with the peptide. The 2Fo–Fc density map is contoured at 2.0σ.

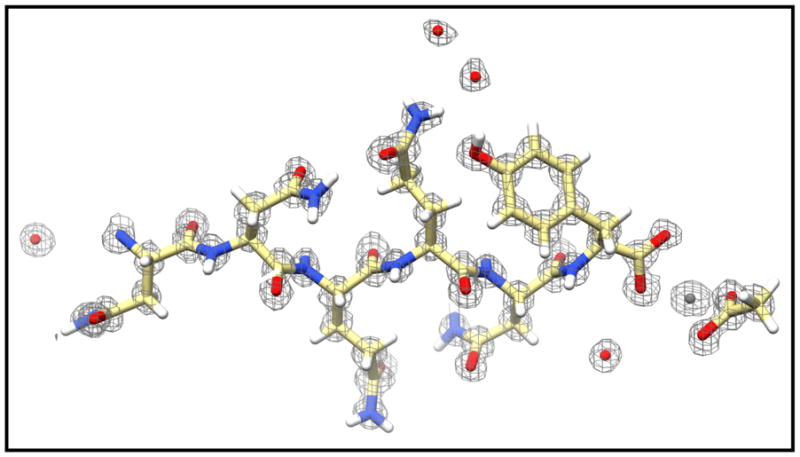

In 2017, the first novel structure of a globular protein complex was determined by MicroED TGF-βm–TβRII [17] (Figure 3). This structure was determined to be 2.9 Å from large imperfect crystals that were fragmented for MicroED data collection. After the MicroED structure was solved, the crystal growth conditions were further optimized to facilitate structure determination by X-ray crystallography by others. It is important to note that no optimization of crystal growth nor of grid preparation nor of data collection was employed for the MicroED work, demonstrating the ability of this method at solving samples directly from sparse matrix crystallization assays.

Figure 3. MicroED structure of the complex TGF-βm–TβRII determined to be 2.9 Å.

A representative region of the interface between the TGF-βm (yellow) and its receptor, TβRII (blue). This structure was determined using data from three microcrystals that had been fragmented from larger poor-quality crystals. The 2Fo–Fc density map is contoured at 1.5σ.

Applications to small-molecule and materials science structures

While MicroED was developed on biological molecules, it can be readily expanded to other fields of study. Electron diffraction of small crystals has been successfully employed to study the structures of materials and small organic molecules using scanning transmission electron microscopy on radiation hardy samples at room temperature [48,49]. Recently, the continuous rotation method [12] was used to collect electron diffraction data and determine the ab initio structure of the small molecules carbamazepine and nicotinic acid [50]. This work was significant as the use of continuous rotation coupled with a fast and sensitive detector allowed the room temperature data collection from these beam-sensitive samples. Electron diffraction has also been a valuable tool for the study of many structures in materials science with many novel structures determined, especially for sensitive compounds such as zeolites and metal organic frameworks [49,51–55]. Continuous rotation data collection facilitated the structure determination of a radiation-sensitive novel zeolite, ITQ-58 [45].

A recent application of MicroED to the field of materials science has come with the study of the atomic structure of a surface-protected gold nanoparticle to sub-angstrom resolution [35]. Metallic nanoparticles display unique optical, electronic, and chemical properties that are of great interest to the scientific community. Despite their great importance, how these nanomaterials form and how their atomic structure determines their unique properties are still unclear. The present study focused on the stable Au146(p-MBA)57 gold cluster, which had resisted previous structure determination. In this work, X-ray diffraction data (1.3 Å) were combined with higher-resolution MicroED data to determine the structure at 0.85 Å (Figure 4). It is important to note that X-rays and X-ray free electron lasers were also tried and yielded low resolution at 1.3 and 1.7 Å, respectively, but MicroED yielded significantly higher resolution. Secondly, these samples contain hydrated gold, so it was important to study the sample in a frozen hydrated state, as one would study protein samples, because upon dehydration the underlying structure was destroyed and no data could be collected. The final structure identified all 146 gold atoms which were organized as a twinned FCC cluster, and was the first structure of a metallic nanoparticle determined by MicroED at sub-angstrom resolution, establishing its use in the field of materials science and nanomaterial structure determination.

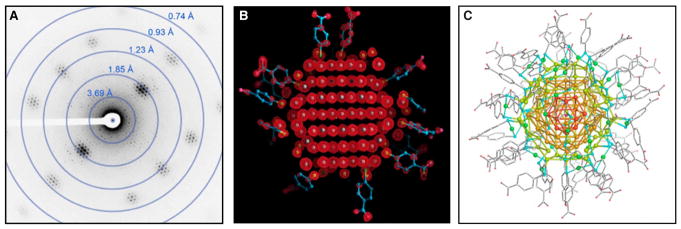

Figure 4. Subatomic resolution MicroED structure of a stabilized gold nanocluster from a single nanocrystal.

(A) Representative diffraction pattern taken of the Au146(p-MBA)57 crystals that shows diffraction extending to ~0.7 Å. (B) The density map (2Fo–Fc; 2σ contour) derived from the MicroED data clearly shows the atomic positions of the gold atoms in the nanoparticle cluster. (C) The final refined structure shows all the gold atoms and the surface capping ligands, and reveals that the nanoparticle is a twinned FCC cluster. Figure adapted from ref. [34].

Conclusions

The ability of MicroED to solve structures from crystals that are considered much too small for conventional diffraction methods opens the door to a wide variety of new discoveries in structural biology, as well as in small-molecule crystallography and materials science. Continued advances in MicroED data collection and processing promise to further expand the technique. One particular area is improved detectors with greater sensitivities and reduced background camera noise that can robustly detect single electron reflections. This would greatly improve the resolution and accuracy obtainable by electron diffraction, as well as potentially allowing diffraction experiments to be performed at even lower electron doses, thereby reducing damage and preserving higher-resolution information. Improvements in the modeling of electron scattering factors promise to bring MicroED into a unique position within the field of structure determination methods. Because electrons scatter off the coulombic potential of the crystal, electron diffraction is very sensitive to charge and chemical bonding [56,57]. With further development and proper modeling, structures determined by MicroED would allow the direct visualization of chemical bonding. In the four short years since the first MicroED structure, the method has proved to be very useful, and the continued advancement of the technique in the following years and decades only promises to further establish MicroED as a versatile tool for structure determination in the future.

Summary.

MicroED is a cryoEM method capable of determinig high resolution structures from nano crystals a billion times smaller in size than what is necessary for X-ray crystallography.

MicroED has been successful at determining structures of proteins, protein complexes, oligopeptides, drugs and small organic molecules as well as material science samples such as hydrated gold clusters.

Abbreviations

- CMOS

complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor

- cryoEM

cryo-electron microscopy

- cryo-TEM

cryo-transmission electron microscope

- MicroED

micro-electron diffraction

- XFELs

X-ray free-electron lasers

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The Authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Moraes I, Evans G, Sanchez-Weatherby J, Newstead S, Stewart PDS. Membrane protein structure determination — the next generation. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembranes. 2014;1838(Pt A):78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman HN, Fromme P, Barty A, White TA, Kirian RA, Aquila A, et al. Femtosecond X-ray protein nanocrystallography. Nature. 2011;470:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature09750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang Y, Zhou XE, Gao X, He Y, Liu W, Ishchenko A, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin by femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature. 2015;523:561–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu W, Wacker D, Gati C, Han GW, James D, Wang D, et al. Serial femtosecond crystallography of G protein-coupled receptors. Science. 2013;342:1521–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1244142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenboer J, Basu S, Zatsepin N, Pande K, Milathianaki D, Frank M, et al. Time-resolved serial crystallography captures high-resolution intermediates of photoactive yellow protein. Science. 2014;346:1242–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1259357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S, Hattne J, Reyes FE, Sanchez-Martinez S, Jason de la Cruz M, Shi D, et al. Atomic resolution structure determination by the cryo-EM method MicroED. Protein Sci. 2017;26:8–15. doi: 10.1002/pro.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nannenga BL, Gonen T. Protein structure determination by MicroED. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;27:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nannenga BL, Gonen T. MicroED opens a new era for biological structure determination. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;40:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez JA, Eisenberg DS, Gonen T. Taking the measure of MicroED. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;46:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson R. The potential and limitations of neutrons, electrons and X-rays for atomic resolution microscopy of unstained biological molecules. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28:171–193. doi: 10.1017/S003358350000305X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martynowycz MW, Glynn C, Miao J, de la Cruz MJ, Hattne J, Shi D, et al. MicroED structures from micrometer thick protein crystals. BioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/152504. [DOI]

- 12.Nannenga BL, Shi D, Leslie AGW, Gonen T. High-resolution structure determination by continuous-rotation data collection in MicroED. Nat Methods. 2014;11:927–930. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes CO, Kovaleva EG, Fu X, Stevenson HP, Brewster AS, DePonte DP, et al. Assessment of microcrystal quality by transmission electron microscopy for efficient serial femtosecond crystallography. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;602:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson HP, Makhov AM, Calero M, Edwards AL, Zeldin OB, Mathews II, et al. Use of transmission electron microscopy to identify nanocrystals of challenging protein targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8470–8475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400240111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson HP, Lin G, Barnes CO, Sutkeviciute I, Krzysiak T, Weiss SC, et al. Transmission electron microscopy for the evaluation and optimization of crystal growth. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Struct Biol. 2016;72(Pt 5):603–615. doi: 10.1107/S2059798316001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wampler RD, Kissick DJ, Dehen CJ, Gualtieri EJ, Grey JL, Wang HF, et al. Selective detection of protein crystals by second harmonic microscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14076–14077. doi: 10.1021/ja805983b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de la Cruz MJ, Hattne J, Shi D, Seidler P, Rodriguez J, Reyes FE, et al. Atomic-resolution structures from fragmented protein crystals with the cryoEM method MicroED. Nat Methods. 2017;14:399–402. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi D, Nannenga BL, de la Cruz MJ, Liu J, Sawtelle S, Calero G, et al. The collection of MicroED data for macromolecular crystallography. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubochet J, Booy FP, Freeman R, Jones AV, Walter CA. Low temperature electron microscopy. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1981;10:133–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.10.060181.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grassucci RA, Taylor DJ, Frank J. Preparation of macromolecular complexes for cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3239–3246. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattne J, Reyes FE, Nannenga BL, Shi D, de la Cruz MJ, Leslie AGW, et al. MicroED data collection and processing. Acta Crystallogr, Sect A: Found Adv. 2015;71(Pt 4):353–360. doi: 10.1107/S2053273315010669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arndt UW, Wonacott AJ. The Rotation Method in Crystallography: Data Collection From Macromolecular Crystals. North-Holland Pub. Co., sole distributors for the U.S.A. and Canada, Elsevier/North-Holland; Amsterdam, New York, NY: 1977. p. xvii.p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battye TGG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AGW. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie AGW, Powell HR. Processing diffraction data with mosflm. In: Read RJ, Sussman JL, editors. Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography. Vol. 245. Springer; Dordrecht: 2007. NATO Science Series. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterman DG, Winter G, Parkhurst JM, Fuentes-Montero L, Hattne J, Brewster A, et al. The DIALS framework for integration software. CCP4 Newsl Protein Crystallogr. 2013;49:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabsch W. XDS Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hattne J, Shi D, de la Cruz MJ, Reyes FE, Gonen T. Modeling truncated pixel values of faint reflections in MicroED images. J Appl Crystallogr. 2016;49(Pt 3):1029–1034. doi: 10.1107/S1600576716007196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krotee P, Rodriguez JA, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Reyes FE, Shi D, et al. Atomic structures of fibrillar segments of hIAPP suggest tightly mated β-sheets are important for cytotoxicity. eLife. 2017;6:e12977. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nannenga BL, Shi D, Hattne J, Reyes FE, Gonen T. Structure of catalase determined by MicroED. eLife. 2014;3:e03600. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawaya MR, Rodriguez J, Cascio D, Collazo MJ, Shi D, Reyes FE, et al. Ab initio structure determination from prion nanocrystals at atomic resolution by MicroED. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11232–11236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606287113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi D, Nannenga BL, Iadanza MG, Gonen T. Three-dimensional electron crystallography of protein microcrystals. eLife. 2013;2:e01345. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vergara S, Lukes DA, Martynowycz MW, Santiago U, Plascencia-Villa G, Weiss SC, et al. MicroED structure of Au146(p-MBA)57 at subatomic resolution reveals a twinned FCC cluster. J Phys Chem Lett. 2017;8:5523–5530. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yonekura K, Maki-Yonekura S. Refinement of cryo-EM structures using scattering factors of charged atoms. J Appl Crystallogr. 2016;49:1517–1523. doi: 10.1107/S1600576716011274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clabbers MTB, van Genderen E, Wan W, Wiegers EL, Gruene T, Abrahams JP. Protein structure determination by electron diffraction using a single three-dimensional nanocrystal. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Struct Biol. 2017;73(Pt 9):738–748. doi: 10.1107/S2059798317010348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nederlof I, van Genderen E, Li YW, Abrahams JP. A Medipix quantum area detector allows rotation electron diffraction data collection from submicrometre three-dimensional protein crystals. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69(Pt 7):1223–1230. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913009700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonen T. The collection of high-resolution electron diffraction data. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;955:153–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-176-9_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yonekura K, Kato K, Ogasawara M, Tomita M, Toyoshima C. Electron crystallography of ultrathin 3D protein crystals: atomic model with charges. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3368–3373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500724112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sumner JB, Dounce AL. Crystalline catalase. Science. 1937;85:366–367. doi: 10.1126/science.85.2206.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unwin PNT, Henderson R. Molecular structure determination by electron microscopy of unstained crystalline specimens. J Mol Biol. 1975;94:425–440. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unwin PNT. Beef liver catalase structure: interpretation of electron micrographs. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:235–242. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(75)80111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorset DL, Parsons DF. Electron diffraction from single, fully-hydrated, ox-liver catalase microcrystals. Acta Crystallogr, Sect A. 1975;31:210–215. doi: 10.1107/S0567739475000423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorset DL, Parsons DF. Thickness measurements of wet protein crystals in the electron microscope. J Appl Crystallogr. 1975;8:12–14. doi: 10.1107/S0021889875009430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matricar VR, Moretz RC, Parsons DF. Electron diffraction of wet proteins: catalase. Science. 1972;177:268–270. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4045.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez JA, Ivanova MI, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Reyes FE, Shi D, et al. Structure of the toxic core of α-synuclein from invisible crystals. Nature. 2015;525:486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature15368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorelik TE, Stewart AA, Kolb U. Structure solution with automated electron diffraction tomography data: different instrumental approaches. J Microsc. 2011;244:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2011.03550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mugnaioli E, Gorelik T, Kolb U. ‘Ab initio’ structure solution from electron diffraction data obtained by a combination of automated diffraction tomography and precession technique. Ultramicroscopy. 2009;109:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Genderen E, Clabbers MTB, Das PP, Stewart A, Nederlof I, Barentsen KC, et al. Ab initio structure determination of nanocrystals of organic pharmaceutical compounds by electron diffraction at room temperature using a Timepix quantum area direct electron detector. Acta Crystallogr, Sect A: Found Adv. 2016;72(Pt 2):236–242. doi: 10.1107/S2053273315022500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mugnaioli E, Andrusenko I, Schüler T, Loges N, Dinnebier RE, Panthöfer M, et al. Ab initio structure determination of vaterite by automated electron diffraction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7041–7045. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baerlocher C, Gramm F, Massuger L, McCusker LB, He Z, Hovmoller S, et al. Structure of the polycrystalline zeolite catalyst IM-5 solved by enhanced charge flipping. Science. 2007;315:1113–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.1137920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez-Franco R, Moliner M, Yun Y, Sun J, Wan W, Zou X, et al. Synthesis of an extra-large molecular sieve using proton sponges as organic structure-directing agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3749–3754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220733110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun JL, Bonneau C, Cantín Á, Corma A, Díaz-Cabañas MJ, Moliner M, et al. The ITQ-37 mesoporous chiral zeolite. Nature. 2009;458:1154–1157. doi: 10.1038/nature07957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang YB, Su J, Furukawa H, Yun Y, Gándara F, Duong A, et al. Single-crystal structure of a covalent organic framework. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16336–16339. doi: 10.1021/ja409033p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu JS, Spence JCH. Structure and bonding in α-copper phthalocyanine by electron diffraction. Acta Crystallogr, Sect A: Found Adv. 2003;59(Pt 5):495–505. doi: 10.1107/S0108767303016866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zuo JM, Kim M, O’Keeffe M, Spence JCH. Direct observation of d-orbital holes and Cu–Cu bonding in Cu2O. Nature. 1999;401:49–52. doi: 10.1038/43403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]