Abstract

For millions of Americans living in vulnerable rural and urban communities, their hospital is an important, and often their only, source of health care. As transformation in the hospital and health care field continues, some communities may be at risk of losing access to health care services and the opportunities and resources they need to improve and maintain their health. Integrated, comprehensive strategies to reform health care delivery and payment, within which vulnerable communities can make individual choices based on their needs, support structures, and preferences, are needed.

In this Invited Commentary, the authors outline characteristics and parameters of vulnerable communities as well as the essential health care services that hospitals should strive to maintain locally identified by the American Hospital Association Task Force on Ensuring Access in Vulnerable Communities. They also describe four of nine emerging strategies—recommended by the task force—to reform health care delivery and payment and allow hospitals to provide the essential health care services, along with implementation barriers and how to address them. While this Invited Commentary focuses on vulnerable communities, the four highlighted strategies (addressing the social determinants of health, adopting new and innovative virtual care strategies, designing global budgets, and using inpatient/outpatient transformation strategy), as well as the other five strategies, may have broader applicability for all communities.

Every day, hospitals and health systems are navigating the challenges and opportunities of a constantly changing health care environment. At the American Hospital Association (AHA), we have been focusing on meeting the demands of today and tomorrow by redefining the hospital—or the “H”—to best serve patients and communities, create new models of care and collaboration, address affordability and value, and advance health in the United States.

To advance the health of all patients and all communities, the AHA developed our Path Forward, with a commitment in five areas: access, value, partners, well-being, and coordination.1 The health care field must work to ensure that all individuals have access to affordable and equitable health, behavioral, and social services; provide increased value to individuals; embrace the diversity of individuals and serve as partners in their health, including connecting with them in ways that make sense in the digital age; focus on well-being and partnerships with community organizations; and coordinate and integrate care.2

About one in four Americans, or 77 million people, have multiple chronic conditions, and spending on patients with multiple chronic conditions across the United States consumes 71% of all health care dollars throughout all settings.3 Part of redefining the “H” means adjusting to this new reality—a reality of helping patients with multiple chronic conditions take charge of their health.

Redefining the “H” also requires a focus on quality improvement, population health management, and the shift from volume to value. Ultimately, this transformation will foster seamless coordination of care and integration of services to manage populations effectively, which leads to better outcomes and value for patients and health care providers.

We feel strongly that quality and performance improvements are a critical answer to addressing environmental shifts and challenges in health care. Providing high-quality care is a goal that will not waver even as the structure of the national health care system is in flux, as it is the cornerstone of health care organizations.

Quality Care for Vulnerable Populations and All Communities

For millions of Americans living in vulnerable rural and urban communities, their hospital is an important, and often their only, source of health care. As transformation in the hospital and health care field continues, some communities may be at risk of losing access to health care services and the opportunities and resources they need to improve and maintain their health. Although there are special payment programs currently in place that attempt to account for the unique circumstances of vulnerable communities, what is urgently needed are integrated, comprehensive strategies to reform health care delivery and payment within which vulnerable communities can make individual choices based on their needs, support structures, and preferences.

To this end, health care providers and payers must work together to develop strategies that can preserve and enhance health care services for all Americans. In 2015, the AHA’s Board of Trustees created the AHA Task Force on Ensuring Access in Vulnerable Communities to examine ways in which hospitals and health systems can help ensure access to health care services in vulnerable communities and to identify challenges to doing so. The task force considered a number of integrated, comprehensive strategies that were emerging to reform health care delivery and payment. The ultimate goal of the task force’s work is to provide vulnerable communities and the hospitals that serve them with the tools necessary to determine what the essential health care services they should strive to maintain locally are and what delivery system options will allow them to do so.

In this Invited Commentary, we outline characteristics and parameters of vulnerable communities as well as what we consider to be the essential health care services. We then describe some of the strategies recommended by the task force to reform health care delivery and payment to allow hospitals to provide the essential health care services, along with implementation barriers and how to address them. Although our focus here is on vulnerable communities, these strategies may have broader applicability for all communities.

Characteristics and Parameters of Vulnerable Communities

There is no defined set of factors that can determine whether a community is vulnerable. The AHA task force created a list of characteristics and parameters of vulnerable rural and urban communities. One or more of these characteristics or parameters may be sufficient to identify a vulnerable community:

lack of access to primary care services;

poor economy, high unemployment rates, and limited economic resources;

high rates of uninsurance and underinsurance;

cultural differences that may pose challenges, such as social, cultural, and linguistic barriers that may prevent patients from accessing care;

low education or health literacy levels; and

environmental challenges, which include unsafe streets; asthma exacerbated by air pollution, leading to unnecessary hospitalizations; housing instability, leading to environmental allergens causing symptoms that may result in inappropriate testing; and minimal or no spaces for physical activity or exercise.4

In addition, certain characteristics or parameters may be unique to rural and urban communities. For example, characteristics or parameters of vulnerable rural communities may include a declining and aging population, the inability to attract new businesses, and business closures, while characteristics or parameters of vulnerable urban communities may include a lack of access to such basic needs as food, shelter, and clothing and a disproportionately high disease burden.4

Essential Health Care Services for All

Across communities, the range of health care services needed and the ability of individuals to access health care services varies widely. The AHA task force recommends that access to a baseline level of high-quality, safe, and effective services should be preserved and protected within all communities. These essential health care services are:

primary care,

psychiatric and substance use treatment services,

emergency department and observation care,

prenatal care,

transportation,

diagnostic services,

home care,

dentistry services, and

a robust referral structure to provide all individuals in the community with access to the full spectrum of health care services.4

Part of ensuring access to these essential health care services for vulnerable communities is ensuring that care is equitable and culturally competent. Health care organizations must keep working to eliminate health and health care disparities, which still exist for far too many individuals from racial, ethnic, and cultural minorities. Doing so will require collecting race, ethnicity, language preference, and other sociodemographic data and using those data to stratify quality metrics; increasing cultural competency training for all clinicians and employees; and increasing diversity in health care leadership and governance.

Without diversity and heath equity, there is no quality. Quality, cost, equity, diversity, and community health are inextricably linked. By 2050, one in two residents of the United States is projected to self-identify as either African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, or multiracial, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.5 Yet, sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics continue to determine an individual’s access to safe, quality care, and as the definition of diversity evolves to include gender identity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic, veteran, and disability status, more people are affected.

To address the health care inequities that continue to persist for far too many individuals, a growing number of hospitals and health systems are playing an anchor role in communities. As an example, more than 1,500 hospitals, roughly 25% of all U.S. hospitals, have pledged to take action on specific goals to eliminate health care disparities,6 led by the AHA’s Institute for Diversity and Health Equity.7

Strategies for Ensuring Health Care Access

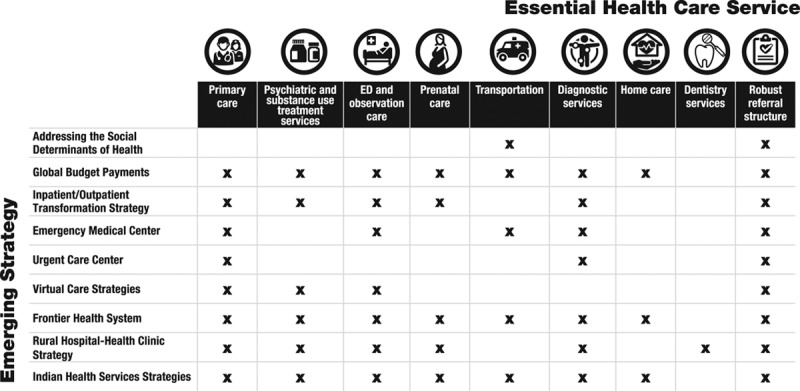

The AHA task force identified nine emerging strategies, each of which offers the opportunity for hospitals and communities to ensure that vulnerable populations have access to the essential health care services (described in detail in the task force report4). Figure 1 lists these emerging strategies and indicates which of the essential health care services the task force suggested each strategy could address.

Figure 1.

Matrix showing nine emerging strategies to reform health care delivery and payment, the essential health care services, and which of the essential health care services each strategy could address, as identified or suggested by the American Hospital Association Task Force on Ensuring Access in Vulnerable Communities. Abbreviation: ED indicates emergency department.

In the remainder of this section, we outline four of the nine strategies. These four strategies are the ones that the AHA believes could have the broadest and most immediate impact.

Addressing the social determinants of health

The task force grappled with the reality that in vulnerable communities, even if quality care is available, the social determinants of health (SDOH; see Figure 2) may prevent individuals from being able to access health care or achieve health goals.

Figure 2.

Examples and descriptions of social determinants of health. The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”13 While this is not a complete list, the social determinants of health given here are among those identified by the American Hospital Association Task Force on Ensuring Access in Vulnerable Communities.

Although there are many ways health care providers could engage to help address the underlying social conditions affecting their patients, the task force identified three general paths:

Screening and information: Providers systematically screen patients for health-related social needs and discuss the impact these challenges may have on their health with them.

Navigation: Providers offer navigation services to assist patients in accessing community services.

Alignment: Providers partner with community stakeholders to more closely align local services with the needs of patients.

(More information about this strategy, including a series of resources on the role that hospitals and health systems can play in addressing the SDOH, is available on the AHA website.8)

Critical to addressing the SDOH is catalyzing cooperation and partnership among health care providers and community-based organizations. To that end, the AHA brought together more than 15 state hospital associations and state health department collaborators to design opportunities to work on violence, the opioid epidemic, and other issues underpinned by the SDOH.

Clinicians also have a key role in collaborations to address these issues. Although clinicians have begun to receive more education and gain experience in enhanced delivery care models and population health management, many lack education and experience collaborating with community-based organizations and addressing situations that illustrate the health impact of clinical–community linkages. For example, clinicians can work with local school districts and public health departments to increase access to primary care and dental services for children and families in underserved neighborhoods. Such clinical–community linkages can help reduce emergency department visits, promote preventive care and healthy behaviors, and connect patients to local organizations to address their specific social needs. Additionally, residency programs have not widely incorporated training on the SDOH into their curricula.

To meet the changing needs of the health care landscape and address health care disparities, residency training programs and health systems can play a role in creating a culture supportive of physicians developing skills and training to recognize and address the SDOH. More than 50% of U.S. medical schools are revising their undergraduate curricula to meet the demands of a dynamic health care system, including learning about the SDOH.9 For example, a recent publication from the Association of American Medical Colleges compiles a series of interesting articles about how medical schools and teaching hospitals are working to address the SDOH and achieve health equity.10

Adopting new and innovative virtual care strategies

The AHA task force believed that virtual care strategies would allow vulnerable communities, particularly those that have difficulty recruiting or retaining an adequate health care workforce, the opportunity to maintain or supplement access to health care services. One virtual care strategy, which provides health care remotely by means of telecommunication technologies, is telehealth. Through videoconferencing, remote monitoring, electronic consults, and wireless communications, telehealth expands patient access to health care services and offers a wide range of benefits, such as:

immediate, around-the-clock access to physicians, specialists, and other health care providers that otherwise would not be available in many communities;

the ability to perform remote monitoring without requiring patients to leave their homes; and

less expensive and more convenient care options for patients.

Therefore, virtual care strategies, such as telehealth, can be used to fill the need for essential health care services in a variety of specialty areas and across diverse patient populations. Currently, smartphones, tablets, and computers can be used to connect patients and physicians directly, but as technology advances, the number of modes through which virtual care can be provided will increase.

Designing global budget payments

The task force also looked at new payment models, such as global budget payments, that could be designed to provide financial certainty for hospitals in vulnerable rural and urban communities. Many factors must be considered when designing these models, including, among other things, the payment levels, types of health care providers and payers that will participate, types of services to be included, and selection of appropriate quality metrics. However, ultimately, global budget payments have the potential to offer providers the flexibility to create a unique plan that meets mandated budgets and that allows them the ability and autonomy to create solutions that work for their communities.

Using inpatient/outpatient transformation strategy

The task force also recommended that an inpatient/outpatient transformation strategy would allow hospitals to more closely align the services they offer with those needed by their communities. That is, hospitals would conduct a detailed assessment of the level of inpatient and outpatient services needed in their community. Then they would take the following three steps to achieve better alignment:

reduce inpatient capacity to a level that closely reflects the community’s need for acute inpatient beds;

shift resources to enhance outpatient and primary care services offered to the community as needed; and

continue providing emergency services.4

Barriers and Resources to Address Them

For each of the nine strategies, barriers to implementation include limited federal funding, restrictive federal regulations, and a lack of collaboration and buy-in from community stakeholders (including public health departments, educational and faith-based organizations, government agencies, fire and police departments, local businesses and service organizations, and other health care organizations). Even with federal policy changes, vulnerable communities and the hospitals that serve them may not have the resources needed to successfully adapt emerging strategies on their own. Some resources for overcoming barriers include applying for grants and establishing learning networks to share information and ideas. However, the most important resource may be hospital–community partnerships.

The building of hospital–community partnerships can bring together a variety of individuals and organizations to address implementation barriers and make a bigger impact than either the hospital or a community organization could do on its own. This collaborative approach is effective because different stakeholders are addressing similar issues and serving the same populations; thus working together creates an opportunity to align efforts, reduce duplication, optimize financial resources, and, ultimately, improve the overall health and well-being of the community.

The AHA’s Health Research & Educational Trust, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, developed A Playbook for Fostering Hospital–Community Partnerships to Build a Culture of Health,11 which includes practical tools, worksheets, and actionable strategies to build consensus and accountability within a partnership. An accompanying compendium of case studies describes nine communities with vulnerable patient populations that have developed and sustained successful hospital–community partnerships, many with multiple stakeholders.

The AHA has also designed a Community Conversations Toolkit,12 which can be used to engage community members in discussions related to health services offered in the community. The toolkit offers ways to focus the engagement of specific stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, and hospital leaders, through community conversation events, social media, and the use of a community health assessment. The toolkit also gathers several AHA resources that address community engagement into one place.

Working Together for Integration and Transformation

It is more important than ever that hospitals and other health care organizations build and maintain strong linkages with a diverse group of community stakeholders to ensure that the needs of vulnerable communities are supported in the future. Collaboration through community health assessments and other strategic endeavors will be vital as a foundation for identifying health priorities and aligning efforts to address them. In addition, hospitals and other community stakeholders will need to work together to identify barriers that could prevent populations from achieving good health, unite around shared goals, and work collaboratively to implement changes that promote a healthier community, while also developing a sustainable business model. Improving access to care and the value of care in vulnerable communities will involve developing innovative ways to use limited resources and to transform care for changing communities.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Cynthia Greising for her editorial assistance with this Invited Commentary.

Footnotes

Editor’s Note: This New Conversations contribution is part of the journal’s ongoing conversation on social justice, health disparities, and meeting the needs of our most vulnerable and underserved populations.

To read other New Conversations pieces and to contribute, browse the New Conversations collection on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/pages/collectiondetails.aspx?TopicalCollectionId=61), follow the discussion on AM Rounds (academicmedicineblog.org) and Twitter (@AcadMedJournal using #AcMedConversations), and submit manuscripts using the article type “New Conversations” (see Dr. Sklar’s announcement of the current topic in the November 2017 issue for submission instructions and for more information about this feature).

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.American Hospital Association. Strategic plan: AHA Path Forward. https://www.aha.org/2017-12-11-strategic-plan-aha-path-forward. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 2.American Hospital Association. 2017–2020 strategic plan: Advancing health in America. https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-01/2018-strategic-plan.pdf. Updated 2018. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple chronic conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/multiple-chronic.htm. Accessed March 6, 2018.

- 4.American Hospital Association. Task Force on Ensuring Access in Vulnerable Communities. https://www.aha.org/system/files/content/16/ensuring-access-taskforce-report.pdf. Published November 29, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2018.

- 5.Colby SL, Ortmann JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060—Population Estimates and Projections. 2015. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Equity of Care. Equity of Care website. http://www.equityofcare.org/. Accessed March 6, 2018.

- 7.Institute for Diversity and Health Equity. Institute for Diversity and Health Equity website. http://www.diversityconnection.org/. Accessed March 6, 2018.

- 8.American Hospital Association. Social determinants of health. https://www.aha.org/social-determinants-health. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 9.Satterfield JM, Mitteness LS, Tervalon M, Adler N. Integrating the social and behavioral sciences in an undergraduate medical curriculum: The UCSF essential core. Acad Med. 2004;79:6–15.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association of American Medical Colleges. Achieving Health Equity: How Academic Medicine Is Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. 2016. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; https://www.aamc.org/download/460392/data/sdoharticles.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Research & Educational Trust; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; American Hospital Association. A Playbook for Fostering Hospital–Community Partnerships to Build a Culture of Health. 2017. Chicago, IL: Health Research & Educational Trust; https://www.aha.org/system/files/hpoe/Reports-HPOE/2017/A-playbook-for-fostering-hospitalcommunity-partnerships.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Hospital Association. Ensuring Access in Vulnerable Communities: Community Conversations Toolkit. 2017. Washington, DC: American Hospital Association; http://www.aha.org/content/17/community-conversations-toolkit.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Reference cited in Figure 2 only

- 13.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/. Accessed March 30, 2018.