Abstract

Rationale:

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), like other neutrophilic dermatosis, may be associated with a variety of systemic disorders including inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and hematologic disorders. Conversely, the association between PG and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has rarely been reported.

Patient concerns:

We report here 2 cases of this association.

Diagnoses:

The first case involves a 32-year-old woman who developed, 1 year after SLE diagnosis, 3 painful nodular lesions of PG on her face, and cervical area. The second case was observed in a 37-year-old woman referred for ulcerative nodular papules of PG on her legs, whereas she had been diagnosed with SLE 10 years before. SLE was inactive in the first case, whereas PG occurred during a lupus flare up in the second one.

Interventions:

We found 23 previous cases of SLE and PG in the literature with most cases (12/20) occurring during a lupus flare.

Outcomes:

Although rare, this association may be supported by common innate immunity dysregulation and abnormal neutrophil activation.

Lessons:

PG and other neutrophilic diseases reported in patients with SLE may be added to the large clinical spectrum of cutaneous lesions observed in SLE.

Keywords: NETosis, neutrophilic dermatoses, pyoderma gangrenosum, systemic lupus erythematosus

1. Introduction

Neutrophilic diseases (NDs) are a heterogenous group of conditions characterized by the accumulation of neutrophils in the skin that may also involve many other organs.[1,2] The pathophysiology of ND is poorly understood but this group of diseases shares clinical and pathologic aspects with autoinflammatory syndromes. A clinicopathologic classification has been proposed, subdividing them into deep or hypodermal forms, whose prototype is pyoderma gangrenosum (PG); plaque type or dermal forms, whose prototype is Sweet syndrome; and superficial or epidermal forms.[1] Among this spectrum, PG typically presents with single or multiple skin ulcers with undetermined erythematous-violaceous borders, but different variants have been distinguished: ulcerative PG, pustular PG, bullous PG, superficial vegetative PG, and peristomal PG.

PG like other ND may be associated with a variety of systemic disorders.[1–3] In a study on a large series of PG patients, disease associations are reported in approximately one-third of cases, including inflammatory bowel diseases (20.2%), rheumatoid arthritis (11.8%), and hematologic disorders (3.9%).[3] PG may precede, coexist, or follow the different systemic diseases. PG can also arise as a consequence of drug therapies and may be observed in autoinflammatory syndromes, especially in the PAPA syndrome (Pyogenic sterile Arthritis, Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne) and in the PASH syndrome (Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, Suppurative Hidradenitis).[1,4]

Conversely, the association between PG and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has been rarely reported. We report 2 cases of this association. We also discuss the possible pathophysiologic links between the 2 entities and have performed a literature review of previously published cases.

2. Case 1

Patient 1 was a 32-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes complicated by retinopathy with occlusion of the left central retinal vein in 2008, Sjogren syndrome since 2011, and SLE since 2014. SLE diagnosis was based on the association of a malar rash, photosensitivity, alopecia, lymphopenia, antinuclear antibodies positivity at a 1/640 dilution (indirect immunofluorescence on Hep2 cells), anti-DNA antibodies identified by Farr assay at 7 IU/mL (N < 5 IU) and low complement levels. No antiphospholipid antibodies were detected. Her SLE was treated with hydroxychloroquine and acetylsalicylic acid without corticosteroids.

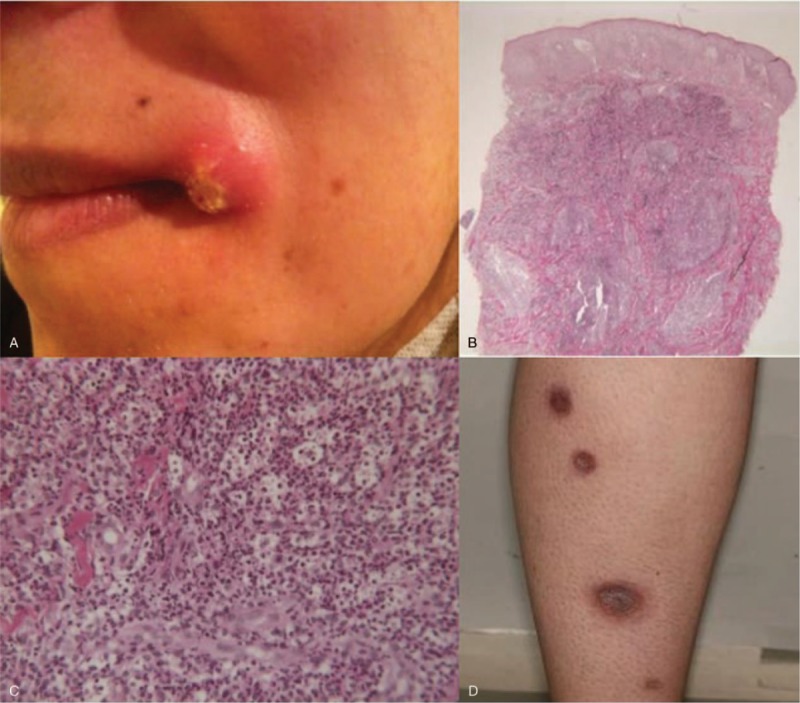

One year after SLE diagnosis, 3 painful nodular lesions with surrounding inflammation and erythema developed at the inner canthus of the left eye (1 × 1 cm), at the left corner of the lips (2 × 2 cm), and in the cervical area (2.5 × 3 cm), respectively (Fig. 1A). No clinical signs of lupus activity were present.

Figure 1.

(A) Lesion at the left angle of the mouth in patient 1. Histopathologic findings of cervical skin lesion of patient 1 revealing dermal neutrophilic infiltration without any granuloma nor vascular damage (hematoxylin-eosin-saffron stain). (B) Original magnification ×25. (C) ×200. (D) Multiple ulcerative papules of the posterior side of the right leg of patient 2.

Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia at 10.2 g/dL, the absence of inflammatory syndrome, normal liver, and kidney function with physiologic proteinuria. Anti-DNA antibodies were measured at 6 IU/mL by the Farr assay (N < 5 IU). Complement was normal.

Histologic examination of the left cervical lesion showed a dense infiltration of dermis by leukocytoclastic or intact neutrophils, without any granuloma nor vascular damage (Fig. 1B, C). No pathogens including atypical mycobacteria or yeast were evidenced. The diagnosis of ulcerative variant of PG was retained.

A treatment with dermocorticoids and minocycline was started up, and complete resolution of PG was obtained within 6 months. Treatment was then discontinued. The patient did not present any recurrence of PG to date, with a 3-year follow-up.

3. Case 2

A 37-year-old woman was referred for ulcerative nodular lesions that had appeared on her legs within the last preceding weeks.

She had a medical history of peptic ulcer, Hashimoto thyroiditis, and Raynaud syndrome. In addition, she had been diagnosed with SLE 10 years before, in postpartum, given the association of lupus-specific skin lesions, nonerosive peripheral arthritis, antinuclear antibodies and anti-DNA antibodies. IgG anti-cardiolipin antibodies were positive at 21 IU (normal <20 IU) only once, whereas anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies and lupus anticoagulant were never detected in her serum. Low dose oral prednisone (between 9 and 30 mg/d) as well as hydroxychloroquine was prescribed since 10 years.

Clinical examination revealed multiple ulcerative papules of the posterior side of her legs (Fig. 1D), malar rash, inflammatory arthralgia of the hands. Histologic examination of ulcerations showed extensive neutrophilic infiltration in the entire height of the dermis. In addition, bleeding suffusions in the superficial dermis, thrombosis in several vessels of the reticular dermis, and hyperplasia of the epidermis were noticed. There was neither suppurative necrosis nor pathogens. Anti-DNA antibodies were positive and serum complement proteins were low. The diagnoses of ulcerative PG and lupus flare up were retained. Dapsone followed by colchicine and low doses of oral corticosteroids was first given but both were rapidly stopped because of side effects (cutaneous rash and gastrointestinal intolerance, respectively). Finally, oral corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/d) and methotrexate 30 mg per week allowed a complete healing of the PG and lupus lesions within months. Methotrexate was continued, while prednisolone was slowly decreased until 10 mg/d. To date, we have a 3-year follow-up, no recurrence of PG has been observed, whereas a flare up of lupus arthritis was diagnosed 2 years later.

4. Discussion

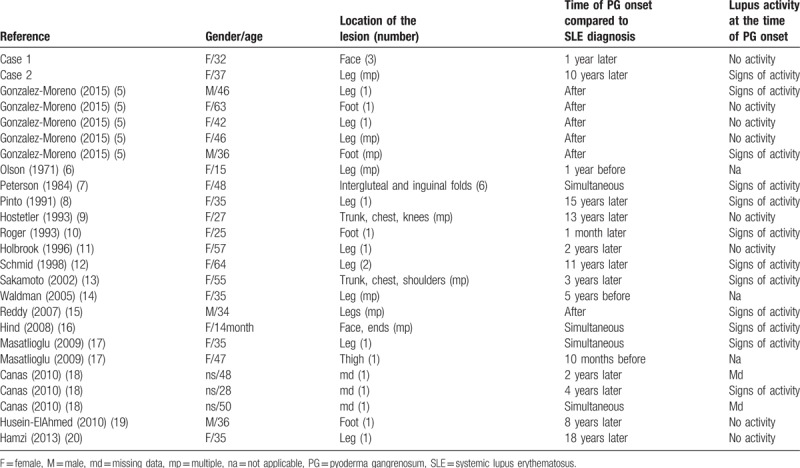

We report here, 2 cases of women with SLE and ulcerative PG. No absolute criteria for the diagnosis of PG are available, but 2 groups proposed similar criteria we used. Both cases fulfilled the 3 major criteria and 2 minor criteria proposed by these groups.[1] Few cases of PG associated with SLE have been reported to date. We found 22 cases of SLE and PG association in the literature, 1 PG/SLE/SGS association and 4 PG/SGS association.[5–24] Main features of the 23 cases of PG associated with SLE and our 2 additional patients are recapitulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main features of the 25 cases of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

PG affects individuals of all ages, with a peak incidence between 20 and 50 years of age, and affects men and women almost equally.[1,3] However, there is a female predominance in nonmalignancy-associated PG.[1] Among the reported cases of patients with PG in a context of SLE, a large majority were women (18/22 cases for which gender was reported).[5–20] These patients with SLE were younger (mean age 40.8 ± 14.7 years), than those with idiopathic PG or with PG associated with other conditions (mean age of 50.3, 59, and 61.5 years, respectively, in 3 different series of PG in the literature).[3,25,26]

Our 2 patients had ulcerative PG but the variant of PG was rarely specified in the 23 previously published.[5–20] No histologic difference was observed between SLE-associated PG and PG related to other conditions.[1,3]

Among the 23 cases of SLE-associated PG reported in the literature, most of the patients (16/23, 69%) had been diagnosed with SLE before the onset of PG, whereas PG was observed before the first symptom of SLE in only 3/23 cases.[5–20] Both diseases appeared simultaneously in 4 cases. In both cases described here, diagnosis of SLE preceded the development of PG, as observed in the majority of the published cases of such association.

Concerning the possible link between lupus activity and PG development, we analyzed in the literature, the clinical and biologic markers of lupus activity for the 20 patients diagnosed with SLE when PG occurred.[5–20] We found clinical symptoms of active lupus and/or complement consumption at the time of PG onset in 12/20 cases, no sign of lupus activity in 6 cases. In 2 cases, the clinical and biologic descriptions were not sufficient to determine lupus activity.

No guidelines are available concerning PG treatment in the setting of lupus. The therapeutic strategy in the general context of neutrophilic dermatosis consists in modulating activation, maturation or migration of neutrophils (with colchicine, dapsone, corticosteroids, and maybe minocycline). Interestingly, drugs able to modulate connective tissue diseases activity like SLE (such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide) were reported effective on neutrophilic skin lesions in the literature.[5–21] This observation suggests that SLE and PG may share some common points in their pathogenesis.

The pathophysiology of PG is still unclear. An increasing body of evidence supports the role of proinflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1-beta, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha in the pathophysiology of NDs similarly to classic monogenic autoinflammatory diseases.[1,27] Multiple proinflammatory genes have been previously reported as highly upregulated in lesional skin of PG: STAT1, STAT3, TYK2, IL8, CCL5, IL-β, IL1R1, CD40, and CD40LG.[27] Overexpression of some Pattern Recognition Receptors, like Toll-like receptors, has also been recently reported in lesional skin.[28]

In SLE, the role of innate immunity has been a rapidly expanding area of research over the last decade. Immune complexes can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, and SLE-derived macrophages are hyper-responsive to innate immune stimuli, leading to enhanced activation of the inflammasome and production of inflammatory cytokines.[29] Recent data indicate also that among innate immune cells, neutrophils could particularly take part to the pathogenesis of SLE.[30] Under various stimulations, neutrophils are able to generate extracellular structures, termed “NETs” (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps), notably containing DNA and histones. NETs display bacteriostatic function and participate in pathogens elimination. Growing evidences suggest that aberrant NETs generation may occur in noninfectious conditions such as autoimmune diseases and may contribute to the breaking of tolerance toward nuclear antigens exposed on traps. In patients with SLE, an imbalance between NETs formation and clearance has been evidenced that may participate in tolerance breaking, initiation of autoimmunity as well as in organ damages.[30] Taken together, these recent data may lead us to think that the association of PG and SLE may not be fortuitous.

Interestingly, other NDs have been observed in the setting of SLE like neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis, Sweet syndrome, palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis, amicrobial pustulosis of the folds, and bullous lupus eythematosus.[31–33] All those observations have lead some physicians to delineate a new nosologic group of cutaneous lesions in SLE, referred as neutrophilic cutaneous lupus erythematosus.[34]

5. Conclusion

Although rare, the association of SLE and NDs like PG may be supported by common innate immunity dysregulation and abnormal neutrophil activation. PG and other NDs reported in patients with SLE may be added to the large clinical spectrum of neutrophilic cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions.[34]

Author contributions

Writing – original draft: Delphine Lebrun.

Writing – review & editing: Ailsa Robbins, Maxime Hentzien, Ségolène Toquet, Julie Plee, Anne Durlach, Jean-David Bouaziz, Firouzé Bani-Sadr, Amélie Servettaz.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: IL = interleukin, NDs = neutrophilic diseases, NET = neutrophil extracellular traps, PG = pyoderma gangrenosum, SGS = Sjogren syndrome, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus, TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

Patients have given their informed consent for the case report to be published.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Marzano AV, Borghi A, Wallach D, et al. A comprehensive review of neutrophilic diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018;54:114–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Soutou B, Vignon-Pennamen D, Chosidow O. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Rev Med Int 2011;32:306–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.revmed.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Langan SM, Groves RW, Card TR, et al. Incidence, mortality, and disease associations of pyoderma gangrenosum in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132:2166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Marzano AV, Trevisan V, Gattorno M, et al. Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PAPASH): a new autoinflammatory syndrome associated with a novel mutation of the PSTPIP1 gene. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:762–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gonzalez-Moreno J, Ruiz-Ruigomez M, Callejas Rubio JL, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum and systemic lupus erythematosus: a report of five cases and review of the literature. Lupus 2015;24:130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Olson K. Pyoderma gangrenosum with systemic L.E. Acta Derm Venereol 1971;51:233–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Peterson LL. Hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:379–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pinto GM, Cabecas MA, Riscado M, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: response to pulse steroid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:818–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hostetler LW, von Feldt J, Werth VP. Cutaneous ulcers in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:91–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Roger D, Aldigier JC, Peyronnet P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 1993;18:268–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holbrook MR, Doherty M, Powell RJ. Post-traumatic leg ulcer. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:214–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schmid MH, Hary C, Marstaller B, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with the secondary antiphospholipid syndrome. Eur J Dermatol 1998;8:45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sakamoto T, Hashimoto T, Furukawa F. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Dermatol 2002;12:485–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Waldman MA, Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum Preceding the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatology 2005;210:64–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Reddy V, Dziadzio M, Hamdulay S, et al. Lupus and leg ulcers - a diagnostic quandary. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:1173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hind A, Abdulmonem AG, Al-Mayouf S. Extensive ulcerations due to pyoderma gangrenosum in a child with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and C1q deficiency. Ann Saudi Med 2008;28:466–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Masatlioglu SP, Goktay F, Mansur AT, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum in two cases. Rheumatol Int 2009;29:837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Canas CA, Duran CE, Bravo JC, et al. Leg ulcers in the antiphospholipid syndrome may be considered as a form of pyoderma gangrenosum and they respond favorably to treatment with immunosuppression and anticoagulation. Rheumatol Int 2010;30:1253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Husein-ElAhmed H, Callejas-Rubio JL, Rios Fernandez R, et al. Effectiveness of mycophenolic acid in refractory pyoderma gangrenosum. J Clin Rheumatol 2010;16:346–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hamzi AM, Bahadi A, Alayoud A, et al. Skin ulcerations in a lupus hemodialysis patient with hepatitis C infection: what is your diagnosis? Iran J Kidney Dis 2013;7:191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hau E, Vignon Pennamen MD, Battistella M, et al. Neutrophilic skin lesions in autoimmune connective tissue diseases: nine cases and a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Sjogren syndrome. Eur J Dermatol 2009;19:392–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tsai YH, Huang CT, Chai CY, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: intractable leg ulcers in Sjogren's syndrome. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2014;30:486–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yamanaka K, Murota H, Goto H, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum and annular erythema associated with Sjögren's syndrome controlled with minocycline. J Dermatol 2015;42:834–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saracino A, Kelly R, Liew D, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum requiring inpatient management: a report of 26 cases with follow up. Australas J Dermatol 2011;52:218–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol 1997;137:1000–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Marzano AV, Cugno M, Trevisan V, et al. Role of inflammatory cells, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in neutrophil-mediated skin diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 2010;162:100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ortega-Loayza AG, Nugent WH, Lucero OM, et al. Dysregulation of inflammatory gene expression in lesional and non-lesional skin of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:e35–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu J, Berthier CC, Kahlenberg JM. Enhanced inflammasome activity in systemic lupus erythematosus is mediated via type I interferon upregulation of interferon regulatory factor 1. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1840–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Leffler J, Martin M, Gullstrand B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps that are not degraded in systemic lupus erythematosus activate complement exacerbating the disease. J Immunol 2012;188:3522–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Larson AR, Granter SR. Systemic lupus erythematosus-associated neutrophilic dermatosis: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol 2014;21:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schissler C, Velter C, Lipsker D. Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds: where have we gone 25 years after its original description? Ann Dermatol Venereol 2017;144:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gusdorf L, Bessis D, Lipsker D. Lupus erythematosus and neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis. A retrospective study of 7 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lipsker D, Saurat JH. Neutrophilic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. At the edge between innate and acquired immunity. Dermatology 2008;216:283–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]