Abstract

Background:

Music therapy combined with cognitive restructuring could provide a mechanism to improve patients’ sense of control over emotional distress. This study evaluates the effect of music therapy combined with cognitive restructuring therapy on emotional distress in a sample of Nigerian couples.

Methods:

The participants for the study were 280 couples in south-east Nigeria. Perceived emotional distress inventory (PEDI) was used to assess emotional symptoms. Repeated measures with analysis of variance were used to examine the effects of the intervention. Mean rank was also used to document the level of changes in emotional distress across groups. Effect sizes were also reported with partial η2.

Results:

There were no significant baseline differences in emotional distress level between participants in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group and waitlisted group. Significant decreases in the level of emotional distress were observed in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, but the waitlisted group demonstrated no significant change in their score both at posttreatment and 3 follow-up assessments.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy is effective for reducing emotional distress of couples. In addition, the positive effect of the music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy program can persist at follow-up. Therefore, therapists have to continue to examine the beneficial effects of music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy on emotional distress level of couples both in Nigeria and in other countries.

Keywords: cognitive restructuring therapy, emotional distress, music therapy, Nigerian married couples

1. Introduction

Many Nigerian families are dysfunctional due to emotional pains among the couples[1,2] and it increases with each decade of life.[3] At present, the increasing rates of domestic disputes among the families are becoming violent and deadly.[2] Due to the rising profile of emotional distress among Nigerian couples, many families are facing marital crises.[4,5] About 53.3% of Nigerian female spouses experience emotional distress linked to sexual dysfunction.[6] Earlier studies indicated that about 20% of spouses are experiencing acute emotional distress.[7] In addition, substantial evidence also supported the high level of emotional distress among Nigerian married couples.[8–14] Among ever-married women, 20% were classified as experiencing emotional distress, and about 52% showed that they experienced physical abuse in their home.[15] An estimated 70% of all cases of emotional distress among the married women were linked to partner abuse.[15] The emotional well-being of many patients has been compromised due to dysfunctional marital relationships.[16,17]

Living with an emotionally distorted partner is associated with emotional distress.[18–20] The consequences of emotional distress do not only affect the individual but also have severe negative effects on their families.[21,22] Emotional distress results in reduced quality of parenting,[23,24] increased risk of emotional and developmental difficulties in the children,[25] reduced quality of life,[26] anxiety, mood, and sleep disorders.[2] Several studies have found that there is a positive relationship between emotional distress and marital dissatisfaction in the general population across gender.[27–30] Emotional distress has been shown to be a precursor to depression,[31] and it negatively impacts on children.[32,33] It, therefore, becomes imperative to develop empirically supported interventions for couples to help them manage emotional distress. The present study aimed to explore the effect of music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy on married couples suffering from emotional distress.

Music therapy could be implemented as a rehabilitative tool for various emotionally distressed outcomes such as depression, mood disturbances, anxiety, nausea, fear, anger, sadness, and pain.[34,35] Music therapy is the use of therapeutic skill of music and musical elements (structured and audible sounds) by music therapists to support, sustain, and reinstate psychological, physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing.[36] Music therapy can be used as a therapeutic tool to promote wellness, alleviate chronic emotional pain, and express feelings and in helping emotionally disturbed individuals.[37] Music therapy is a helpful strategy used in alleviating the feelings of patients with life-limiting illnesses.[38,39] Music therapy is effective for treating persons with emotional distress, anxiety,[40] and pain.[41] Listening to improvised music may improve treatment of cognitive symptoms of emotional distress in that it helps individuals with emotional distress to relax their nervous systems, feel comfortable, and pay inattention on stressful events.[42] On that note one could infer that the presence of a music therapist is needed even when listening to composed or live music is presented.[42] This is because music can induce strong emotional relief and provides psychotherapeutic support to people with mood disturbances.[42] Music therapy is capable to influence psychologic state, cognition and emotions, which has an impact on family life.[34]

Cognitive restructuring approach may influence the management of emotional distress among Nigerian couples. Cognitive restructuring is a therapeutic technique used to assist individuals to modify stress-inducing assumptions and belief systems. The concern of cognitive restructuring is to help the stress-inflicted couple to replace illogical feelings with more accurate ones. Cognitive restructuring could change patient's maladaptive and irrational beliefs to achieve rational and logical attitude towards family life.[43] Cognitive restructuring could be an effective method for reducing emotional distress.[44,45] Researchers[46] showed that cognitive restructuring has a significant effect on the reduction of emotional distress. Music therapy with cognitive restructuring has been suggested to provide a means of helping people to pay inattention to possible stimuli that causes emotional distress, creating images and carrying a person's thoughts away from the noxious stimuli.[2] Music therapy with cognitive restructuring could provide a mechanism to improve patients’ sense of control over emotional distress. To our knowledge, there is lack of empirical studies which have simultaneously examined the effect of music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy on emotional distress among couples in Nigeria. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy on emotional distress in a sample of Nigerian couples. It was hypothesized that level of emotional distress would be lowered after the music therapy with cognitive restructuring among the treatment group when compared to a waitlisted group.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval

The researchers were granted approval to conduct the research by their Departmental Research Ethics Committee at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The established Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct of American Psychological Association were also held onto by the researchers. The study also complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Design

The study is a pretest–posttest control group design.

2.3. Participants

The participants for the study were 280 married couples in south-east Nigeria. The screening and selection process were based on the inclusion criteria. Those that meet up with inclusion criteria were asked to fill a written consent form for each procedure that was taken.

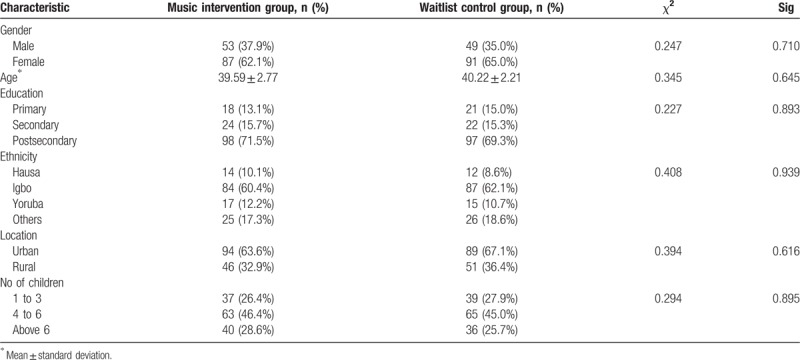

Table 1 shows that the mean age of the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group was 39.59 ± 2.77 years, and that of the waitlist control group was 40.22 ± 2.21 years (χ2 = 0.227, P = .645). The music therapy with cognitive restructuring group comprised 53 men (37.9%) and 87 (62.1%) women; the waitlist control group comprised 49 men (35.0%) and 91 (65.0%) women. From the analysis of results, it can be seen that no significant gender difference was observed in the evaluation for the intervention among the participants (χ2 = 0.247, P = .710). In the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, 18 participants (13.1%) had a primary school certificate, 24 participants (15.7%) had a secondary school certificate, and 98 (71.5%) had a postsecondary certificate. For the participants in the waitlist control group, 21 participants (15.0%) had a primary school certificate, 22 participants (15.3%) had a secondary school certificate, and 97 (69.3%) had a postsecondary certificate (χ2 = 0.227, P = .893). Regarding ethnicity, in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, 14 (10.1%) were from Hausa, 84 (60.4%) were from Igbo, 17 (12.2%) were from Yoruba, and 25 (17.3%) were from other minor ethnic groups. In the waitlist control group, 12 (8.6%) were from Hausa, 87 (62.1%) were from Igbo, 15 (10.7%) were from Yoruba, and 26 (18.6%) were from other minor ethnic groups (χ2 = 0.408, P = .939). Of those in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, 46 (32.9%) were from rural areas and 94 (63.6%) were from urban areas. Of the participants in the waitlist control group, 51 (36.4%) were from rural areas and 89 (67.1%) were from urban areas (χ2 = 0.394, P = .616). In the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, 37 (26.4%) had 1 to 3 children, 63 (46.4%) had 4 to 6 children, and 40 (28.6%) had above 6 children. For the participants in the waitlist control group, 39 (27.9%) had 1 to 3 children, 65 (45.0%) had 4 to 6 children, and 36 (25.7%) had above 6 (χ2 = 0.294, P = .895).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

2.4. Procedure

The researchers visited churches, market places, and schools, for identification of the eligible participants. The researchers adopted the perceived emotional distress inventory (PEDI) for the screening of participants.[47] The inclusion criteria were the presence and severity of emotional distress among potential participants and completion of informed consent form. The recruitment of the participants lasted from July to October, 2015. The researchers administered the PEDI as a pretest before the music therapy with cognitive restructuring intervention (“Time 1”) to obtain baseline data. Couples (n = 280) who expressed a high level of emotional distress were selected as participants. Participation in the study was voluntary.

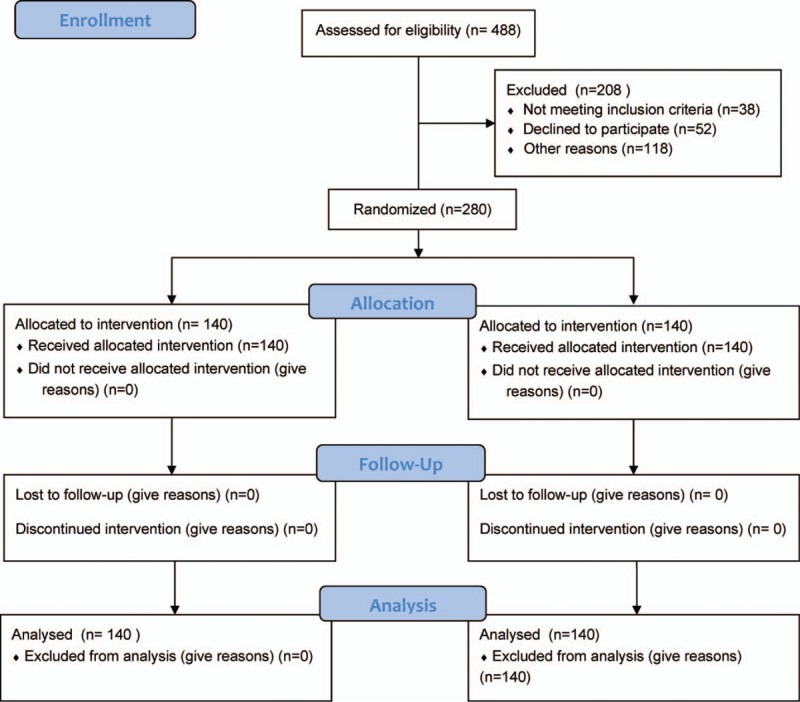

The eligible participants were assigned to a music therapy with cognitive restructuring group (140 couples) and a waitlist control group (140 couples) using a simple randomization. This is a method in which the participants picked a card from inside a container. The cards were labeled with “MTCG” (for music therapy with cognitive restructuring group) and the other “WG” for waitlist group. The participants who picked MTCG were assigned into treatment group while those who picked WG were respectively assigned into waitlist group (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram for participants’ allocation.

Informed consent letters were sent to 12 musicians and 12 counselors to serve as research assistants. The musicians were vocalists, drummers, pianists, violinists, and guitarists. Their genres of professional music experiences include blues, opera, rock, theater, pop, classical, and folk music. The counselors were 3 mental health and rehabilitation counselors, 6 family counselors, and 3 cognitive-behavioral counselors. The counselors ensured that the intervention program incorporated cognitive restructuring elements as intended. The researchers, musicians, and counselors supervised all sessions.

The music therapy with cognitive restructuring group met twice a week for 12 weeks consecutively. At end of the treatment, the participants were assessed for posttreatment outcome (Time 2). Three additional time points (3, 6, and 12 months after the final session) were scheduled a week for follow-up meetings. During the follow-up meetings, 90 minutes sessions were held between 11.30 am and 1.00 pm for a meeting. Before the commencement of the intervention, the researchers assured the participants that their privacy and confidentiality would be protected in line with clinical practice. The researchers highlighted and explained the importance of confidentiality and the rights and as well as responsibilities of participants with regard to divulging privacy and limits of confidentiality of information. The researchers compared the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group to the waitlisted group at only Times 1 and 2. The waitlisted group participants were scheduled to begin the music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy immediately after the final follow-up. The researchers collated the data after each assessment from the participants.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Perceived emotional distress inventory

This is a 15-item self-report screening scale designed to assess the presence and severity of anxiety, anger, depression, and hopelessness in patients. The PEDI was developed by Moscoso, Lengacher, and Reheiser.[47] The PEDI is designed on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3: Not at all (0), Sometimes (1), Often (2), Very Much So (3). The PEDI item scoring pattern was based on the global severity index raw scores which is determined by summing the ratings for each individual item.[37] The total score for the PEDI ranges from 0 to 45 points, that is, higher scores correspond to higher levels of perceived emotional distress. The internal reliability consistency of the PEDI was 0.86 alpha based on the present study sample.

2.6. Intervention

2.6.1. Music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy manual

The intervention manual addressed the couples’ emotional distress using therapeutic approaches of music therapy and cognitive restructuring techniques. The researchers educated participants on rhythmic features of music and therapeutic impacts of cognitive reframing. The researchers used the music techniques namely singing which improves articulation, rhythm, breath control, and reduce anxiety and fear. Instruments were played and the researchers also engaged in rhythmic-based activities.[36] The rhythmic-based activities facilitated and improved the motor areas of the brain and regulated autonomic processes such as breathing and heart rate, and maintaining motivation or activity level. In addition, the intervention manual contained lyric discussion and songwriting to help the individual participant to deal with marriage-related painful memories, trauma, abuse, and express feelings and thoughts that are normally socially unacceptable. Participants were also assisted to improve cognitive skills such as attention and memory. The participants were given assignments to practice cognitive restructuring techniques at home. In other words, at the end of each meeting, individual participants had homework assignments to complete and ensure that they brought feedback to the researchers regarding assignments completion.

2.7. Statistical and data analysis

This is a pretest–posttest control group design study. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to document the effect of the music therapy combined with cognitive restructuring therapy. Mean rank was also used to document the changes in emotional distress across the groups. Effect sizes were also reported with partial η2. To report differences in participant demographic variables, we made use of Chi-square (χ2) statistic. Screening for missing values and violation of assumptions was done by the researchers. All statistical analyses were completed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

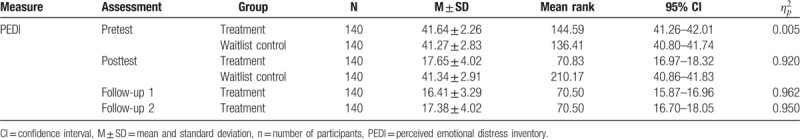

The results in Table 2 show the study outcomes for the participants in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group compared to the waitlisted group over 4 periods. At Time 1, based on the PEDI, the 1-way ANOVA test indicated that there were no baseline differences in emotional distress level between participants in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group and waitlisted group, F(1, 279) = 1.416, P = .235,  = 0.005. The repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant treatment by time interaction effect, F(1, 279) = 3198.43, P = .000,

= 0.005. The repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant treatment by time interaction effect, F(1, 279) = 3198.43, P = .000,  = 0.920. Follow-up tests (Time 3) revealed significant reductions in levels of emotional distress, F(1, 279) = 3486.159, P = .000,

= 0.920. Follow-up tests (Time 3) revealed significant reductions in levels of emotional distress, F(1, 279) = 3486.159, P = .000,  = 0.962, for the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group. Follow-up tests (Time 4) also revealed significant reductions in levels of emotional distress, F(1, 279) = 2622.658, P = .000,

= 0.962, for the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group. Follow-up tests (Time 4) also revealed significant reductions in levels of emotional distress, F(1, 279) = 2622.658, P = .000,  = 0.650, for the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group.

= 0.650, for the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis showing the music therapy combined with cognitive restructuring therapy intervention treatment effect on emotional distress by group.

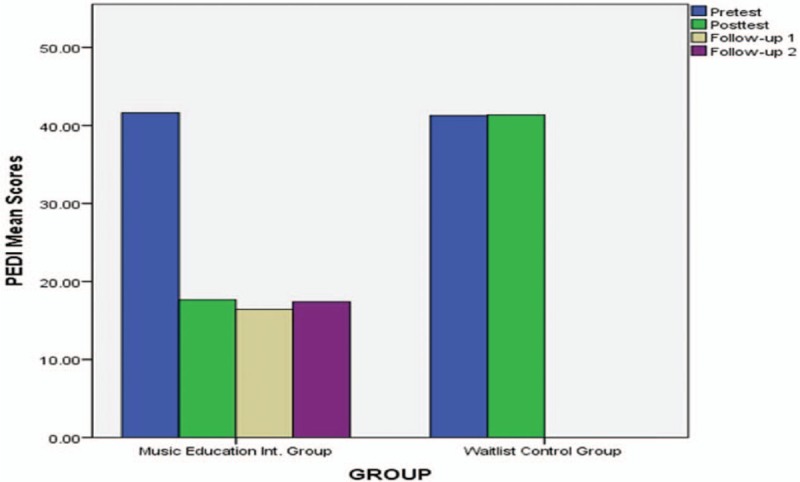

As can be seen in Figure 2, significant reductions in levels of emotional distress were observed at both postintervention and follow-ups in those participants exposed to the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group compared with those in the waitlisted group.

Figure 2.

Emotional distress across the time points. PEDI = perceived emotional distress inventory.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to investigate the effect of music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy on emotional distress in a sample of Nigerian couples. Our findings showed that there were no baseline differences in emotional distress level between participants in the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group and the waitlisted group. We also found a significant treatment by time interaction effect for severity of emotional distress. We found significant decreases in level of emotional distress for the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, but the waitlisted group demonstrated no significant change in their score over the same period. The follow-up tests revealed further that there was significant reductions in levels of emotional distress for the music therapy with cognitive restructuring group but participants in the waitlisted group showed no such significant improvements. The findings of the present study are consistent with Svansdottir[48] who showed that music therapy is a remedial approach that reduces emotional distress symptoms like activity disturbances, aggressiveness, and anxiety among patients. Previous research indicated that music therapy alters automatic thoughts and emotional distress.[35] In consonance with our findings, music therapy was confirmed to be a therapeutic tool in helping individuals with emotional pains.[37] Previous research supported that music therapy is a helping strategy that improves healthy emotional state and alleviating the feeling of patients with life-limiting illnesses.[38] Other clinical research studies have found treatment effect of music therapy for persons with emotional distress symptoms such as anxiety.[40] It was noted that music therapy has strong positive significance on emotions and memories family life.[34]

Cognitive-restructuring reduces the distress, pains, and emotional instability.[45] Generally, the music therapy combined with cognitive restructuring therapy may be helpful for clinicians, family counselors, and music therapists who work with different category of couples in identifying and altering their unhealthy ideas, enhancing psychologic functioning, and increasing their ability to effectively manage family stress and dysfunctions. Thus, music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy can be seen as an effective family health therapy program for managing emotional distress and warrants further application. Given that the cognitive restructuring therapy has been used and a positive effect was recorded,[49] the researchers feel that further application of music therapy with cognitive restructuring intervention to improve the psychological health and well-being of couples is warranted both in Nigeria and in other countries.

Like other studies, the present study had some limitations. Study sample was 280 which is large enough for this study. Moreover, the power estimation proved that it was sufficient for researchers to truly observe the effect. The participants in this study were limited to couples in south-east Nigerians born and married in Nigeria. Considering a good number Nigerian couples who are residing in Diaspora, the researchers would encourage future studies to focus on Nigerian population in Diaspora. The use of only quantitative data in this study also limits its contribution to the extant literature. Therefore future studies should look into qualitative data.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy can be used to assist married couples to cope with emotional distress. Music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy significantly reduced the level of emotional distress in those participants exposed to the treatment intervention in comparison to a waitlisted group. In addition, the positive effect of the music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy persisted at follow-up periods. Therefore, therapists are urged to continue to examine the beneficial effects of music therapy with cognitive restructuring therapy on emotional distress level of couples both in Nigeria and in other countries.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Rifkatu Bulus Ali.

Data curation: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike.

Formal analysis: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike.

Funding acquisition: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Joachim C. Omeje, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M. Eze, Grace N. Omeje, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Investigation: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M. Eze, Grace N. Omeje, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Methodology: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike.

Project administration: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M Eze, Grace N. Omeje, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Resources: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Joachim C. Omeje, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M. Eze, Grace N. Omeje, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Software: Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Kelechi R. Ede, Joachim C. Omeje, Rifkatu Bulus Ali.

Supervision: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Kelechi R. Ede, Joachim C. Omeje, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M Eze, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Validation: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Visualization: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O Nwaubani, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Joachim C. Omeje, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M. Eze, Grace N. Omeje, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Writing – original draft: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Eucharia N. Aye, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Rifkatu Bulus Ali.

Writing – review & editing: Bernedeth N. Ezegbe, Moses Onyemae chi Ede, Chiedu Eseadi, Okechukwu O. Nwaubani, Immaculata N. Akaneme, Kelechi R. Ede, Joachim C. Omeje, Chukwuemeka Ezurike, Charity N. Onyishi, Rifkatu Bulus Ali, Ngozi M. Eze, Grace N. Omeje, Uchenna Ugwu, Justina Ofuebe.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANOVA = analysis of variance, χ2 = chi-square, CI = confidence interval, M ± SD = mean and standard deviation, MTCG = music therapy with cognitive restructuring group, n = number of participants, PEDI = perceived emotional distress inventory, WG = waitlist group.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Omoaregba JO, James BO, Lawani AO, Morakinyo O. Psychosocial characteristics of female infertility in a tertiary health institution in Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2011;10:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Okpara BA. Qualitative study of Nigerian couples in the United States: examining emotional reactivity and the concept of differentiation of self. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Akron, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- [3].Davis MP, Srivastava M. Demographics, assessment and management of pain in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2003;20:23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Amadi UPN, Amadi FNC. Marital crisis in the Nigerian society: causes, consequences and management strategies. Mediterr J Soc Sci 2014;5:133–43. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mwantu EN, Kazi TT, Damilep JZ, et al. Influence of psychological divorce among parents on children's psycho-emotional well-being. Niger J Appl Behav Sci 2014;2:176–83. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nwagha UI, Oguanuo TC, Ekwuazi K, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among females in a university community in Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2014;17:791–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Esan O, Akinsulore A, Yusuf MB, et al. Assessment of emotional distress and parenting stress among parents of children with clubfoot in south-western Nigeria. SA Orthop J 2017;16:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Adekeye OA, Abimbola OH, Adeusi SO. Domestic violence in a semi-urban neighbourhood. Gender Behav 2011;9:4247–61. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Amole TG, Bello S, Odoh C, et al. Correlates of female-perpetrated intimate partner violence in Kano, Northern Nigeria. J Interpers Violence 2016;31:2240–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dim EE, Ogunye O. Perpetration and experience of intimate partner violence among residents in Bariga local community development area, Lagos State, Nigeria. J Interpers Violence 2017. 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Igbokwe CC, Ukwuma MC, Onugwu KJ. Domestic violence against women: challenges to health and innovation. Jorind 2013;11:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ilika AL, Okonkwo PI, Adogu P. Intimate partner violence among women of childbearing age in a Primary Health Care Center in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2002;6:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iliyasu Z, Abubukar IS, Aliyu MH, et al. Prevalence and correlates of gender-based violence among female university students in Northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2011;15:111–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Okemgbo C, Omidiyi AK, Odimegwu CO. Prevalence, patterns and correlates of domestic violence in selected Igbo communities of Imo State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2002;6:101–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ellsberg M, Caldera T, Herrera A, et al. Domestic violence and emotional distress among Nicaraguan women: results from a population-based study. Am Psychol 1999;54:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull 2001;127:472–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Waltz M, Badura B, Pfaff H, et al. Marriage and the psychological consequences of a heart attack: a longitudinal study of adaptation to chronic illness after 3 years. Soc Sci Med 1988;27:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].van Wijngaarden B, Schene AH, Koeter MW. Family caregiving in depression: impact on caregivers’ daily life, distress, and help seeking. J Affect Disord 2004;81:211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Idstad M, Ask H, Tambs K. Mental disorder and caregiver burden in spouses: the Nord-Trondelag health study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Røsand GB. Relationship satisfaction, emotional distress, and relationship dissolution: a population-based study on pregnant women and their partners. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oslo, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baronet AM. Factors associated with caregiver burden in mental illness: a critical review of the research literature. Clin Psychol Rev 1999;19:819–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ohaeri JU. The burden of caregiving in families with a mental illness: a review of 2002. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2003;16:457–65. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005;46:479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lyons-Ruth K, Wolfe R, Lyubchik A. Halfon N, K. Taaffe Mc Learn, Schuster MA, et al. Depressive symptoms in parents of children under age 3: sociodemographic predictors, current correlates and associated parenting behaviors. Child Rearing in America: Challenges Facing Parents with Young Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. 217–62. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ramchandani P, Psychogiou L. Paternal psychiatric disorders and children's psychosocial development. Lancet 2009;374:646–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H. Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: a critical examination of the self-report methodology. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Beach SRH, Smith DA, Fincham FD. Marital interventions for depression: empirical foundation and future prospects. Appl Prev Psychol 1994;3:233–50. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Psychological Aspects of Depression Toward a Cognitive Interpersonal Integration. New York: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zlotnick C, Kohn R, Keitner G, et al. The relationship between quality of interpersonal relationships and major depressive disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Affect Disord 2000;59:205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dehle C, Weiss RL. Sex differences in prospective associations between marital quality and depressed mood. J Marriage Fam 1998;60:1002–11. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rehman US, Gollan J, Mortimer AR. The marital context of depression: research, limitations, and new directions. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:179–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Baucom DH, Shoham V, Mueser KT, et al. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:53–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hahlweg K, Markman HJ, Thurmaier F, et al. Prevention of marital distress: result of a German prospective longitudinal study. J Fam Psychol 1998;12:543. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Finnerty R. Music therapy as an intervention for pain perception. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- [35].Magill-Levreault L. Music therapy in pain and symptom management. J Palliat Med 1993;9:42–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Canadian Association for Music Therapy. Understanding of what kind of musical interventions. Available at: http://musictherapy.ca. Accessed April 14, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Knapp C, Madden V, Wang H, et al. Music therapy in an integrated pediatric palliative care programme. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2009;26:449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Periyakoil V, Hallenbeck J. Identifying and preparatory grief and depression at the end of life. Available at: http://.www.aafp.org/afp/20020301/881.html. Accessed May 17, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].O’Kelly J. Music therapy in palliative care: current perspective. Int J Palliat Nurs 2009;8:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Daykin N, Bunt L, McClean S. Music and healing in cancer care: survey of supportive care providers. Arts Psychotherapy 2006;33:402–13. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Renn CL, Dorsey SG. The physiology and processing of pain: a review. AACN Clin Issues 2005;16:277–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bradt J, Potvin N, Kesslick A, et al. The impact of music therapy versus music medicine on psychological outcomes and pain in cancer patients: a mixed methods study. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:1261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ghamari KH, Rafeie SH, Kiani AR. Effectiveness of cognitive restructuring and proper study skills in the reduction of test anxiety symptoms among students in Khalkhal Iran. AERJ 2015;3:1230–6. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mehryar H. Comparison of effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. MA thesis, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Institute of Psychiatry, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kaviani H, Pournaseh M, Sayadlou S, et al. Effectiveness of stress management training in reducing anxiety and depression, participants in class exam. New J Cognitive Sci 2007;8:61–8. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hill KT, Wigfield A. Test anxiety: a major educational problem and what can be done about it. Elem Sch J 1984;85:105–26. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Moscoso MS, Lengacher CA, Reheiser EC. The assessment of the perceived emotional distress: the neglected side of cancer care. Psicooncologia 2012;9:277–88. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Svansdottir HB. Music therapy in moderate and severe dementia of Alzheimer's type: a case control study. Int Psychogeriatr 2006;18:613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mindell JS, Coombs N, Stamatakis E. Measuring physical activity in children and adolescents for dietary surveys: practicalities, problems and pitfalls. Proc Nutr Soc 2014;73:218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]