Abstract

Background

The mechanism of esophageal pain in patients with nutcracker esophagus (NE) and other esophageal motor disorders is not known. Our recent study shows that baseline esophageal mucosal perfusion, measured by laser Doppler perfusion monitoring (LDPM), is lower in NE patients compared to controls. The goal of our current study was to perform a more detailed analysis of esophageal mucosal blood perfusion (EMBP) waveform of NE patients and controls to determine the optimal EMBP biomarkers that combined with suitable statistical learning models produce robust discrimination between the two groups.

Methods

Laser Doppler recordings of 10 normal subjects (mean age 43 ±15 years, 8 males) and ten patients (mean age 47± 5.5 yrs., 8 males) with NE were analyzed. Time and frequency domain features were extracted from the first twenty-minute recordings of the EMBP waveforms, statistically ranked according to four independent evaluation criterions, and analyzed using two statistical learning models, namely, logistic regression (LR) and support vector machines (SVM).

Key Results

The top 3 ranked predictors between the two groups were the 0.5 and 0.75 perfusion quantile values followed by the surface of the EMBP power spectrum in the frequency domain. ROC curve ranking produced a cross-validated AUC (area under the curve) of 0.93 for SVM and 0.90 for LR.

Conclusions & Inferences

We show that as a group NE patients have lower perfusion values compared to controls, however, there is an overlap between the two groups, suggesting that not all NE patients suffer from low mucosal perfusion levels.

Keywords: Esophageal wall blood perfusion, nutcracker esophagus, time and frequency domain predictors, machine learning

Graphical Abstract

Abbreviated abstract

The goal of our study was to perform a detailed time and spectral domain analysis of the esophageal mucosal blood perfusion (EMBP) waveform from of NE patients and controls to determine the optimal EMBP biomarkers that combined with suitable statistical learning models may produce robust discrimination between the two groups.

INTRODUCTION

The connection between unexplained chest pain and esophageal spasm was first described by William Osler in 1892. The term Nutcracker esophagus that describes patients with high amplitude contractions on manometry was first coined in 19791; in connection with “angina like” chest pain of esophageal origin. The precise mechanism by which NE causes pain is not known. Current thinking is that esophageal pain is not related to high amplitude contractions, instead these patients are thought to have a hypersensitive esophagus. The latter implies that the stimuli that do not elicit pain in healthy subjects do so in these patients, e.g., they sense esophageal distension at a lower balloon volume as compared to normal subjects2, 3.

Similar to myocardial ischemia as a mechanism of cardiac angina (chest pain), ischemia of the bowel wall is an important cause of abdominal pain. Low perfusion of esophageal wall as a mechanism of esophageal pain has been suspected for long time4–6; however, the concept did not gain much ground because of the lack of accurate and reproducible methodology to record esophageal wall blood flow/blood perfusion in humans. Using a novel methodology in which a laser Doppler probe is anchored to the esophageal mucosa, we found that with each esophageal contraction there is significant reduction in the esophageal mucosal blood perfusion (EMBP), or in other words the blood flows into the esophageal wall in-between esophageal contractions7. In another study, we found that patients with NE have low EMBP as compared to asymptomatic healthy controls8 suggesting the possibility that low blood flow to the esophageal wall may be a mechanism of esophageal pain. Therefore, the mucosal perfusion recording using laser Doppler technique is an important signal that can provide important insight into the pathogenesis of esophageal pain. The goal of our present study is to layout a systematic framework in analyzing EMBP recordings to determine, 1) the biomarkers (waveform parameters) that could be extracted from these recordings and, 2) whether a robust prediction model could be built to distinguish NE patients from the asymptomatic controls, based solely on EMBP.

METHODS & EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Subjects

Laser Doppler recordings of the esophageal mucosal blood perfusion (EMBP) from 10 healthy volunteers (mean age 43 ±15 years, 8 males) and ten patients (mean age 47± 6 yrs., 8 males) with NE were analyzed for this study. Some of these data were part of a recently published manuscript8. Briefly, these patients were recruited from the esophageal clinic/GI function laboratory of the University of California San Diego (UCSD). Cardiac etiology of pain was excluded by appropriate standard of care testing in each subject, prior to their inclusion in the study. All patients had a prior high resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) study with the diagnosis of high amplitude contractions (NE, mean contraction amplitude of > 180mmHg in the distal esophagus)‥ These patients had failed a trial of acid inhibition therapy, i.e., double-dose proton pump inhibition (PPI) therapy. An important inclusion criterion for our study was the presence of frequent/daily chest pain symptoms. The protocol for the studies was approved by the “University of California San Diego Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Humans”. Subjects fasted and stopped smoking for 6 hours prior to the study.

Data Acquisition

The EMBP was monitored using a custom designed laser Doppler probe (Periflux system 5000, AB, Box 564 SE-175 26 JãrFãlla, Stockholm, Sweden) anchored to the esophageal wall (figure 1 A & B), as described previously7. Briefly, the Laser Doppler probe was firmly taped to a Bravo pH capsule using a paraffin film (figure 1 B). The laser beam exits from the laser Doppler probe in the direction and at the level of the suction cup of the Bravo pH capsule. The laser Doppler signal was calibrated in-vitro using the PF 1001 calibration device (0–250 PU) (from Perimed) prior to placement in each subject. In the majority of subjects, laser Doppler probe was first passed through the nose and pulled out from the mouth. It was then taped to the side of the Bravo pH capsule and assembly was then introduced through mouth into the esophagus. Bravo capsule was deployed at 5 to 6 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). A HRM catheter (Sierra Scientific, Los Angeles, CA) was passed through the nose and placed into the esophagus. Thus, simultaneous recordings of the esophagus, LES & stomach pressures, esophageal pH and esophageal wall blood perfusion (EMBP) were obtained. All recordings were synchronized manually using event markers on the 3 recorders (laser Doppler, pH and HRM), and 8 – 10 wet swallows (5 ml water) were recorded followed by a baseline period of 50–60 minutes. For the analysis, in order to have a uniform comparison across all the subjects, the first 20 minutes of the recording was used, which yielded a 40000 (sampling frequency * time) element EMBP signal for each subject, with total backscatter (TB) value greater than one. The TB is the amount of light reflected back to the laser Doppler probe; it is an indicator of adequate contact between the Doppler probe and esophageal mucosa.

Data Analysis

The perfusion data were imported into Matlab (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) for further analysis. In order to analyze the data, due to the novelty of the EMBP signal itself, an effort was made to build a systematic framework, which includes adequate pre-processing (the laser Doppler signals were despiked to remove artifacts prior to any post-processing (appendix I) to remove unwanted artefacts), feature extraction, feature ranking, and classification/prediction. In the case of esophageal mucosal laser Doppler recordings, one does not know the number of relevant features, which could help differentiate the two groups, therefore, an optimal feature extractor would yield a representation that makes the job of the classifier simpler. So, the challenge is to determine how to adjust the complexity of the model predictors that could explain the differences between controls and NE patients, yet not so complex as to give poor classification on the novel patterns (i.e., generalization). Therefore, we attempted to select a set of informative time and frequency domain features, and a classifier; logistic regression (LR)9, support vector machines (SVM)10 on the ranked feature set or a pruned version of it. Support vector machines (SVMs) are a relatively new method based on the principle of statistical learning theory to solve classification and regression problems. This method tries to learn and generalize well when building a model using a given set of patients. Feature selection is an extremely important aspect of any classification problem, since they are used to build the classifier11. In what follows, we discuss the set of temporal and spectral features extracted from the EMBP signals.

Quantiles

The 0.25, 0.5 (i.e., median), 0.75, 0.95, and the inter quartile range (IQR) of the perfusion data were determined. Quantiles are cut points dividing the range of a probability distribution into contiguous intervals with equal probabilities.

Relative Frequency

We define the relative frequency as the number of instances of perfusion data in a particular range (bins) divided by the total number of data points (equivalent of percent time). Five equal bins, in the increments of 200 units (0–200, 200–400, 400–600, 600–800 and 800–1000 PU) were chosen to build a frequency histogram. The third and fourth order moments, namely, skewness and kurtosis were determined from the frequency histograms. Kurtosis is a measure of whether the data is heavy or lightly tailed relative to normal distribution; high kurtosis tend to have heavy tails, or outliers. Skewness is a measure of symmetry, or more precisely, the lack of symmetry. A symmetric data set is a bell shaped Gaussian distribution.

Power Spectral Density

A study of relationships between the time domain and its corresponding frequency domain representation is also termed as Fourier analysis and Fourier transforms11. The power spectral density (PSD) of a waveform refers to the spectral energy distribution per unit time, and it is an important tool in providing improved diagnosis in the electrocardiogram (EKG) signal 12, 13. For all subjects, the PSD estimate of the input signal was found using Welch's overlapped segment averaging estimator12. Each section is windowed with a Hamming window11. The following features were extracted from the PSDs: total power (TP) computed by integrating the power spectral density (PSD) estimate, and the 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 0.95 quantiles, and the interquartile range (IQR) of the PSD.

Hjorth Parameters

The Hjorth parameters are simple measures of signal variance and structural complexity based on the second moment of the signal, and its first and second difference. These measures have been used in electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis, and are clinically used for the quantitative description of EEG signals14, 15. Mobility measures the ratio between the standard deviation of the slope and the standard deviation of the amplitude given per time unit; hence it represents the dominant frequency. This ratio depends on the curve shape in such a way that it measures the relative average slope. Complexity is a dimensionless parameter that quantifies any deviation from the sine shape as an increase from unit. Finally, Activity, represents the signal power, the variance of a time function, which can indicate the surface of power spectrum in the frequency domain (see appendix II).

Feature Selection & Classification

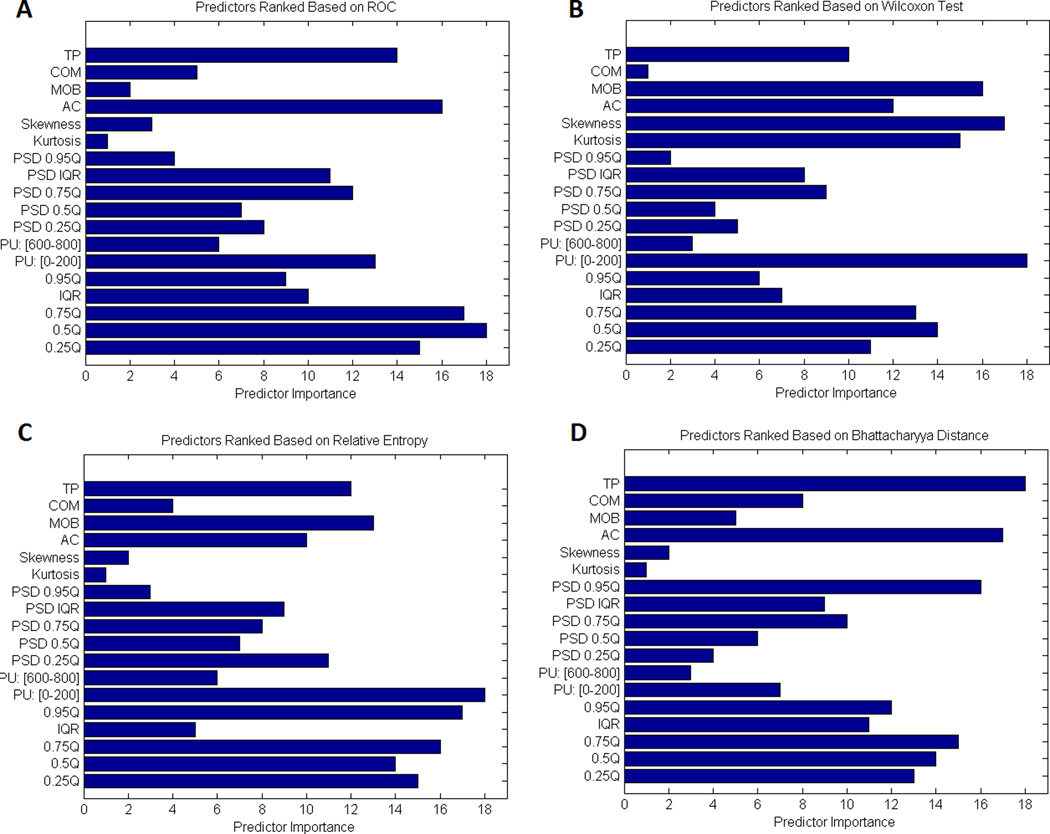

We used 4 different statistical methods to rank the feature set, namely, Wilcoxon test16, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve16, 17, Bhattacharyya distance and the Kullback-Leiber distance, also known as relative entropy16 (see appendix II). We compared the performance of Logistic Regression (LR) and Support Vector Machines that used radial basis functions as kernels for the classification using tenfold cross validation with a 40% hold-out for model evaluation, and the area under the curves were evaluated and compared (see appendix II for further details).

RESULTS

As discussed in the method section, a 20-minute continuous mucosal perfusion time series that included swallows (both dry and wet) was analyzed for each subject. Mean contraction amplitude at any one location in the esophagus of > 180mm Hg was the inclusion criteria for our study. The mean distal contractile integral (DCI), the parameter used in Chicago classification for high amplitude contraction was 6223±2904 mmHg.s.cm in the 10 patients. We analyzed whether a correlation existed between the mean DCI and mean blood perfusion value in patients. We found a small negative correlation between the two (r=-0.15) but it was not statistically significant (p=0.65).

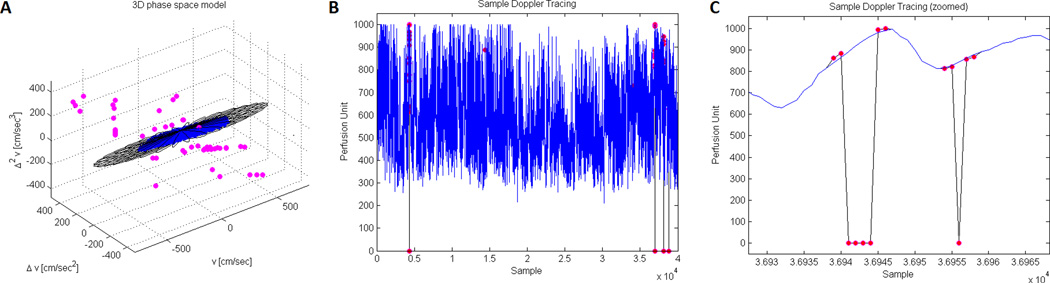

A sample result on one of a subject is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1B, shows the final signal (in blue) overlaid on the original signal (in black), and the detected outlier points (shown in magenta). Finally, Figure 1C, shows a zoomed region between two samples, where after removal of outlier points, the EMBP signal is locally reconstructed (shown in blue) using cubic interpolation.

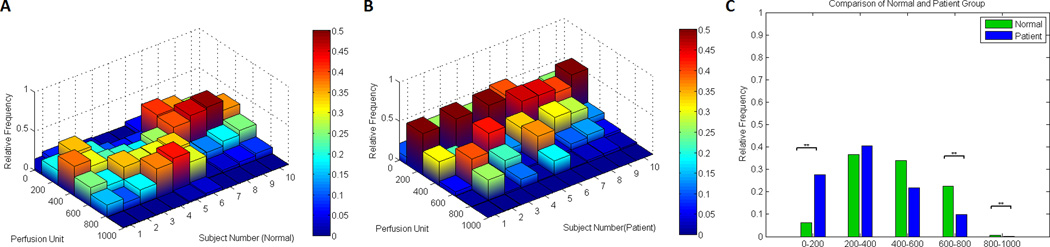

Relative Frequency

The results of the relative frequency count (% time in different perfusion unit bins) is shown in Figure 2. There was significant difference between the two groups for the 0–200 (p=0.014), the 600–800 (p=0.045), and the 800–1000 (p=0.012) perfusion unit bins. The NE patients spent more time in the lower EMBP values, while the reverse was the case in normal subjects.

Quantiles

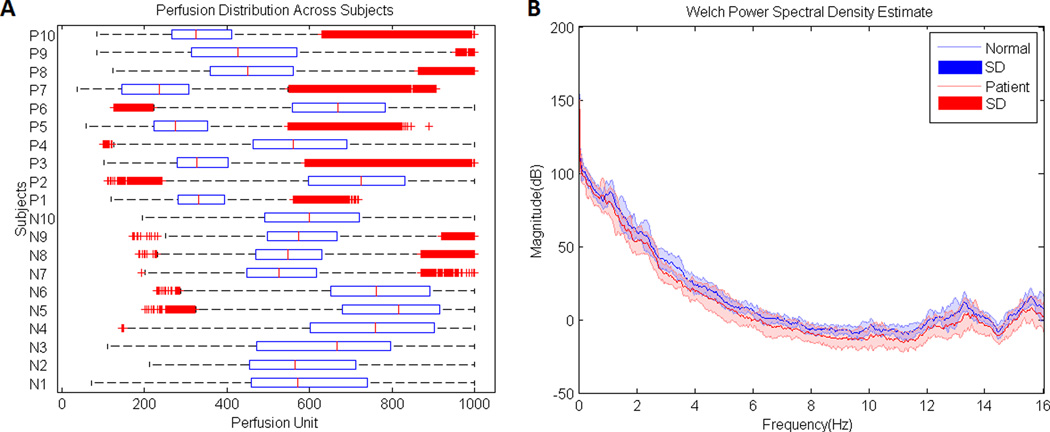

The boxplot of the EMBP data in all subjects is shown in Figure 3A, data points lying outside 1.5 times the interquartile range are shown as red crosses. The median perfusion value in the normal group was 624, IQR=280. One the other hand, the comparable values for the NE group were 398, IQR=309. Wilcoxon rank sum test revealed a statistical significance difference between the medians of the two groups (p=0.011).

Power Spectral Density

Figure 3B shows the mean PSD computed for all the subjects within each group. As it can be seen the amplitude of the PSD is reduced in patients with NE, which was further observed by comparing the median PSD of each individual within the two groups, showing a smaller amount of signal energy in the NE subjects (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p<0.001) suggesting that the power spectral density and energy content of the EMBP waveform is significantly reduced in the NE patients compared to normal subjects.

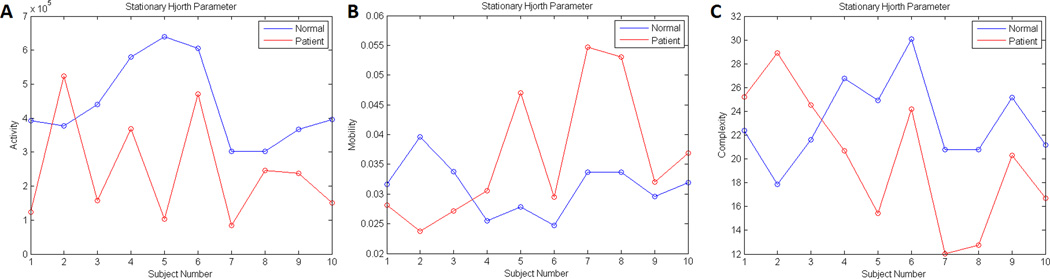

Hjorth parameters

The results of the stationary Hjorth parameters are shown in Figure 4, which compares the three Horthy parameters between the two groups. A two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to the three parameters. The activity (variance) data set show a significant difference between the two groups (p= 0.014), however the complexity and mobility data were not different (p= 0.62 and p= 0.16, respectively).

Feature Selection & Classification

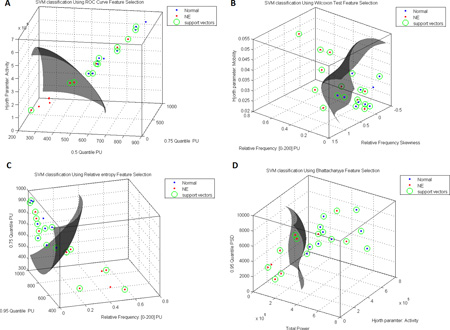

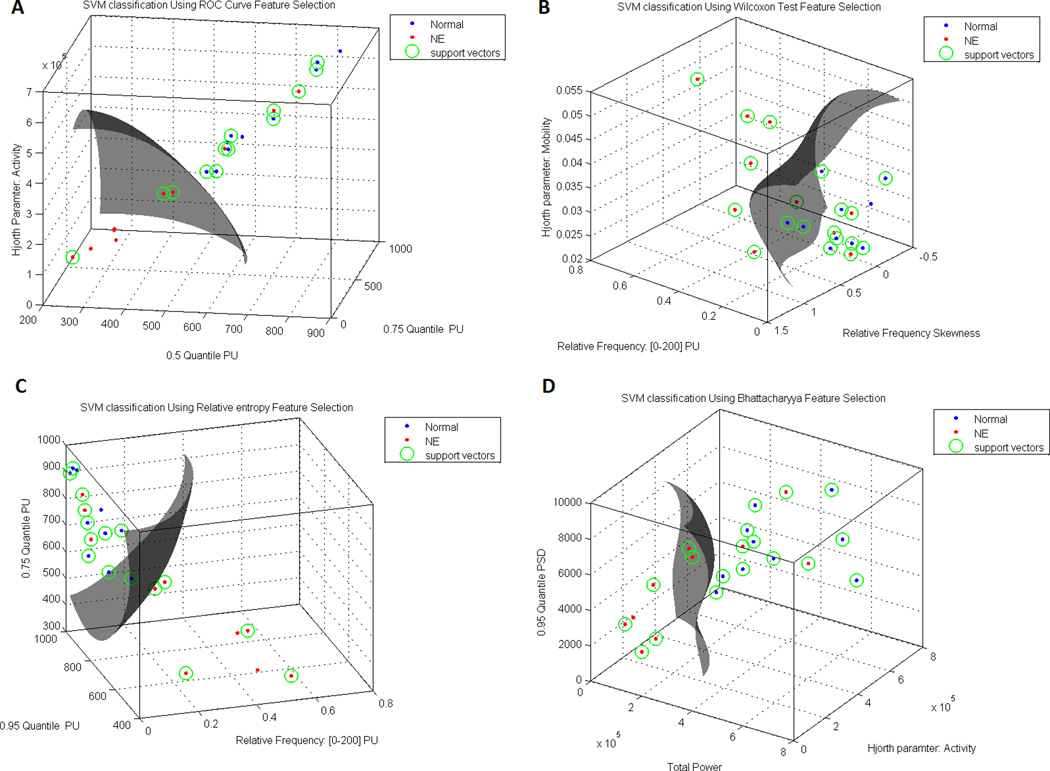

Figure 5 shows the results of applying the different separability criteria to the feature matrix. In each panel, the feature with the longest length has the highest discriminative power according to the particular separability criteria used, while the lower ranked attributes contribute less and less to the discriminating power. In order to evaluate the discrimination power of the predictors, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated. The ROC curves plot the true positive prediction rates versus the false positive prediction rates for various classification-threshold values over the range from near 0 to near 1. Table 1 shows the estimated AUC values comparing logistic regression and support vector machines. The rows of the AUC table, indicate the number of features used for the learning. For example, row one, shows the results of using the first 18 features as ranked by a certain ranking method, and feeding them into the classifier. As it can be seen from this table, SVM performs better than LR. Furthermore, AUC levels indicate correlation structures in the feature data. According to this table, SVM requires less features than LR to achieve a better (or equivalent) misclassification rate. According to this table, the top 3 ranked discriminatory predictors between the two groups are the 0.5 and 0.75 perfusion quantiles followed by the surface of the EMBP power spectrum in the frequency domain, using a ROC ranking, producing a 10-fold cross-validated AUC of 0.93 for SVM and 0.90 for LR. Moreover, the SVM yields the same AUC using only the first 2 prominent features, as ranked by the ROC curve. This was also true for logistic regression, however with a slightly lower value. Figure 6 shown a sample classification of the SVM using the top 3 ranked features for the groups.

DISCUSSION

In a recently published manuscript we examined the laser Doppler EMBPrecordings in patients with NE and compared them with controls using the commercially available software by Perimed. We built a frequency histogram of the EMBP values during the entire period of recordings (2–8 hours) in the two groups and found, 1) the mean baseline value of EMBP during the entire recorded period is lower in patients compared to normal subjects and 2) the frequency histogram is shifted to the left in patients. However, we did not analyze the laser Doppler EMBP waveform in detail, like we did in this manuscript. In the current study, we carried out frequency domain analysis, which requires a continuous waveform in the time domain. However, due to the step response artefacts noise introduced during meals, difference in the length of the recordings, and the administration of drugs post meal, we chose a 20-minute continuous time frame prior to the meal, to have a uniform representative waveform across all subjects. Our results confirm our major finding that as a group, NE patients have lower EMBP values compared to normal subjects but there exists an overlap between the two groups. The features that provide best discrimination between the two groups, high values in the lower EMBP bin and low values in the high perfusion bin in patients, low PSD and less variability in the perfusion values of patients, are all related to the low EMBP in patients.

We present a comprehensive framework for the processing of laser Doppler EMBP data to determine if this novel biomarker is different in patients with NE with non-cardiac chest pain compared to normal subjects. By combining time domain and frequency domain parameters extracted from the EMBP data, we sought a subset of optimal predictors using different separability criteria in choosing an appropriate statistical learning model, to come up with a robust prediction model to differentiate patients from controls. We selected the LR and SVM models for several reasons, 1) they are popular with data analysts, machine learning researchers and statisticians; 2) they can produce accurate class-probability estimates, although there are factors other than accuracy which contribute to the merit of a given classifier. These include simplicity and insight gained into the predictive structure of the data. 3) Multivariate logistic regression intends to build a classification model that fits a set of patients optimally. Unfortunately, this strategy may easily result overfitting the training patients, and leads to poor generalization to previously unknown patients. Support vector machines (SVM) try to learn and generalize well when building a model using a given set of patients. This way, SVMs perform reasonably well on a training set, but not at the expense of performance when making predictions for previously unseen patients. A further disadvantage of logistic regression is that the technique is not able to identify possible nonlinear structures in a set of patients. When nonlinear relationships exist, a nonlinear decision boundary may result in a better performance overall. Unlike logistic regression, SVMs are designed to generate more complex decision boundaries (e.g., see Figure 6) as observed in the higher AUC values produced by the SVM.

Three out of 10 patients in our study have EMBP values in the normal range. We found out there was no statistically significant (linear) correlation between the mean DCI and mean EMBP values in patients arguing against high amplitude contraction as the sole reason for low EMBP. In an earlier study we found that the EMBP values are already quite low as the contraction amplitudes reaches 100mmHg 18. Therefore, any further increase in the contraction amplitude does not necessarily decrease EMBP any further. At this stage, we can only speculate as to why there is overlap between the patients and normal; 1) the depth of penetration of the laser Doppler beam is only 1–2 mm and therefore the laser Doppler perfusion technique in its current format only records blood perfusion only in the superficial mucosa. We can’t be sure whether EMBP recordings are representative of what is happening in the deeper layers, i.e., muscle layers, which may be highly relevant because the muscle layers in patients with various motility disorder differ substantially with regards to its thickness19, 20. 2) Maybe the mechanism of pain is not related to blood perfusion or ischemic in nature in all cases. 3) The NE patients are only a small group of patients with non-cardiac or possibly esophageal pain. The reason for selectively including NE patients in our study was that we wanted to study patients with some objective motility abnormality that is currently associated with esophageal pain, i.e., high amplitude esophageal contraction. The majority of patients with non-cardiac chest pain of esophageal pain actually do not have NE. 4) Pain events are relatively infrequent and their occurrence is mostly unpredictable, therefore another reason is that patients were not necessarily having pain during the first 20 minutes; the time period of data analysis. Studies are in progress in our laboratory to examine a larger population of patients suspected to have esophageal pain with laser Doppler EMBP recordings, which will shed more light if there is a link between low mucosal perfusion of esophagus and “angina like” esophageal pain.

Key Points.

The pathogenesis of esophageal pain is not known. The goal was to test the extent as to which, esophageal mucosal blood perfusion could serve as a predictor of pain in nutcracker patients.

Time and frequency domain features from esophageal mucosal blood perfusion waveforms obtained via laser Doppler monitoring, were statistically ranked, and analyzed.

Results indicate that as a group, NE patients have lower blood perfusion values compared to normal subjects, but there exists an overlap between the two groups.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by a NIH Grant DK060733

Appendix I

EMBP Signal Despiking

Like any other digitized signal, the laser Doppler signal has artefacts that is mainly caused by the loss of contact between the laser beam and esophageal mucosa which produces sharp spike in the Doppler signal 21, 22. These artefacts cause problems in the analysis of EMBP data, and have to be removed without affecting the fidelity of the signal. While several technique have been proposed to eliminate aliasing errors called ‘spikes’ 22, the phase-space thresholding despiking technique appears to be the most efficient and robust method in steady flows 23, 24. The 3D phase space method 23 uses the concept of 3D Poincaré map. In the 3D phase space method, velocity here denoted by v, and its first and second derivatives are plotted against each other. The points located outside of the ellipsoid in the Poincaré map are excluded and the method iterates until the number of detected spikes becomes zero.

Appendix II

Feature Selection

We used 4 different statistical methods to rank the feature set, namely, Wilcoxon test16, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve16, 17, Bhattacharyya distance and the Kullback-Leiber distance, also known as relative entropy16. Selection using statistical hypothesis testing (i.e., Wilcoxon), considers the differences of the medians values corresponding to a specific feature in the two classes, and we test whether these differences are significant. The problem with the Wilcoxon approach is that, the medians values are closely located, the information may not be sufficient to guarantee good discrimination property of a feature passing the test. The median values may be different, yet the spread around the medians may be large enough to blur class distinction. Therefore, we used another approach that focuses on providing information about the overlap between the classes using the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. Finally, the two methods (i.e., Wilcoxon test and ROC curve) are based on measuring class separability, rather than looking at each feature individually, as the two approaches neglect to take into account the correlation that unavoidably exists among the features. Therefore, we used two other popular ‘class separability’ measures, which find the distance between the distribution of the two class features. This is achieved using the Bhattacharyya distance and the Kullback-Leiber distance, also known as relative entropy16, 17.

EMBP Signal Despiking

Like any other digitized signal, the laser Doppler signal has artefacts that is mainly caused by the loss of contact between the laser beam and esophageal mucosa which produces sharp spike in the Doppler signal 21, 22. These artefacts cause problems in the analysis of EMBP data, and have to be removed without affecting the fidelity of the signal. While several technique have been proposed to eliminate aliasing errors called ‘spikes’ 22, the phase-space thresholding despiking technique appears to be the most efficient and robust method in steady flows 23, 24. The 3D phase space method 23 uses the concept of 3D Poincaré map. In the 3D phase space method, velocity here denoted by v, and its first and second derivatives are plotted against each other. The points located outside of the ellipsoid in the Poincaré map are excluded and the method iterates until the number of detected spikes becomes zero.

Hjorth parameters

The Hjorth parameters (activity, mobility and complexity), have been proposed to examine if the signal is oscillatory or not. These parameters quantify the variance of a signal [18], [19]. Denoting the esophageal perfusion signal as, p(t), where t is for time, the Hjorth parameters are as follows:

Activity represents the signal power. Mobility represents the mean frequency and has a proportion of standard deviation of the power spectrum, whereas complexity compares a signal’s similarity to a pure sine wave.

Logistic Regression

In logistic regression (LR) the log of odds for success as a function of the predictors using a linear model is modeled. Logistic regression measures the relationship between the categorical dependent variable and one or more independent variables by estimating probabilities using a logistic function, which is the cumulative logistic distribution 9.

Support Vector Machines

Among numerous classification methods, the support vector machine (SVM) is a popular choice and has attracted much attention in recent years. It uses the idea of searching for the optimal separating hyperplane with maximum separation25. Support Vector Machines (SVM) are machine-learning derived classifiers which map a vector of predictors into a higher dimensional plane through either linear or non-linear kernel functions26. The two groups in a binary classification, are separated in a higher-dimension hyperplane based on a structural risk minimization principle. The goal is to find a linear separating hyperplane built from a vector×of predictors mapped into a higher dimension feature space by a nonlinear feature function. Since, in a two class classification problem, there are infinite separation hyperplanes, the objective is to find the optimum linear plane which separates best the two groups.

Footnotes

COI: None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

Author Contributions:

AZ: Data analysis, figure preparation, and wrote the manuscript

RKM: Conceived the project, designed experiments, data acquisition, and co-wrote the manuscript

YJ: Experimental design, data acquisition, intellectual input

References

- 1.Benjamin SB, Gerhardt DC, Castell DO. High amplitude, peristaltic esophageal contractions associated with chest pain and/or dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:478–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter JE, Barish CF, Castell DO. Abnormal sensory perception in patients with esophageal chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:845–852. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasr I, Attaluri A, Hashmi S, et al. Investigation of esophageal sensation and biomechanical properties in functional chest pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:520–526. e116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacKenzie J, Belch J, Land D, et al. Oesophageal ischaemia in motility disorders associated with chest pain. Lancet. 1988;2:592–595. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustafsson U, Sjoberg F, Tibbling L. Computerized thermistor technique for indirect studies of esophageal blood flow. Dysphagia. 1995;10:117–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00440082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafsson U, Tibbling L. The effect of edrophonium chloride-induced chest pain on esophageal blood flow and motility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:104–107. doi: 10.3109/00365529709000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittal RK, Bhargava V, Lal H, et al. Effect of esophageal contraction on esophageal wall blood perfusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G1093–G1098. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00293.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Y, Mittal RK. Low Esophageal Mucosal Blood Flow in Patients with Nutcracker Esophagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00359.2015. ajpgi 00359 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman DA. Statistical Models: theory and practice. Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning. New York, USA: Springer New York Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard RM. Principles of Random Signal Analysis and Low Noise Design: The Power Spectral Density and its Applications. Wiley-IEEE Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel FA, et al. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science. 1981;213:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.6166045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong Y, Bai Y, Yang B, et al. Autonomic nervous nonlinear interactions lead to frequency modulation between low- and high-frequency bands of the heart rate variability spectrum. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1961–R1968. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00362.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hjorth B. EEG analysis based on time domain properties. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1970;29:306–310. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(70)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidaurre C, Krämer N, Blankertz B, et al. Time Domain Parameters as a feature for EEG-based Brain–Computer Interfaces. Neural Networks. 2009;22:1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theodoridis S, Koutroumbas K. Pattern Recognition. Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Motoda H. Feature Selection for Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Y, Mittal RK. Low Esophageal Mucosal Blood Flow in Patients with Nutcracker Esophagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00359.2015. ajpgi.00359.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal RK, Liu J, Puckett JL, et al. Sensory and motor function of the esophagus: lessons from ultrasound imaging. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:487–497. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dogan I, Puckett JL, Padda BS, et al. Prevalence of increased esophageal muscle thickness in patients with esophageal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:137–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori N, Suzuki T, Kakuno S. Noise of acoustic Doppler velocimeter data in bubbly flow. Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 2007;133:122–125. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voulgaris G, Trownbridge JH. Evaluation of the acoustic doppler velocimeter ADV for turbulence measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1998;15:272–289. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goring DG, Nikora VI. Despiking acoustic doppler velocimeter data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2002;128:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahl TL. Discussion of ‘Despiking acoustic doppler velocimeter data. Hydraul. Eng. 2003;129:484–488. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, et al. Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christianini N, Taylor JS. An Introduction to Support Vector Machines and Other Kernel-Based Learning Methods. cambridge university press; 2000. [Google Scholar]