Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a malignant hematopoietic stem cell disorder that frequently evolves into acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Patients with MDS are prone to infectious complications, in part due to the presence of severe neutropenia and/or neutrophil dysfunction. However, not all patients with neutropenia become infected, suggesting that other immune cells may compensate in these patients. Monocytes are also integral to immunologic defense; however, much less is known about monocyte function in patients with MDS. In the current study, we monitor the composition of peripheral blood monocytes and several aspects of monocyte function in MDS patients, including HLA-DR expression, LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine production, and phagocytosis. We find that monocytes from MDS patients exhibit relatively normal innate immune functions compared to monocytes from healthy control subjects. We also find that HLA-DR expression is moderately increased in monocytes from MDS patients. These results suggest that monocytes could compensate for other immune deficits in MDS patients to help fight infection. We also find that the range of immune functions in monocytes from MDS patients correlates with several key clinical parameters, including blast cell count, monocyte count, and Revised International Prognostic Scoring System score, suggesting that disease severity impacts monocyte function in MDS patients.

Keywords: MDS, PBMC, lipopolysaccharide, phagocytosis, HLA-DR

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a heterogeneous malignant hematopoietic stem cell disorder characterized by arrested differentiation, dysplastic blood cell production, and evolution to acute myeloid leukemia [1–4]. There are believed to be as many as 15,000 new diagnoses of MDS each year in the United States; MDS disproportionately impacts the elderly, with 36/100,000 diagnosed annually in the 80 years and older group [5]. MDS has a poor prognosis, with a 3-year survival rate of only 35% [6]. Infection or infectious complications are one of the most frequent causes of death in MDS patients [7–14]. Neutropenia and neutrophil dysfunction are common features of this disease [15–24]; however, many patients with significant neutropenia do not become infected [9, 11–13, 15, 19, 24–28]. One possibility is that other immune cells may compensate, at least in part, for neutrophil dysfunction in these patients. Like neutrophils, monocytes are critical for combating infection [29], and their importance may be even greater in the setting of neutropenia [30–32]. Monocytes from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) exhibit significant immune dysfunction including an altered monocyte profile and a diminished inflammatory response induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [33–35]. However, the function (or dysfunction) of monocytes in MDS patients remains unclear; the few prior studies concerning this topic have suggested that these immune cells may retain significant function [21, 36–38].

To clarify this issue, we have now analyzed monocyte function from the peripheral blood of 43 patients with MDS (27 untreated and 16 treated) and 14 healthy control subjects. Unlike neutrophils in MDS patients or monocytes in CLL patients, peripheral blood monocytes from patients with MDS retained significant immune function, perhaps helping explain the residual ability to fight infection in some MDS patients with neutropenia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject enrollment and sample collection

These studies were approved by the University of Colorado and National Jewish Health Institutional Review Boards. All subjects, or an appropriate proxy, gave written informed consent. Peripheral blood from MDS patients was collected as part of an IRB-approved tissue acquisition protocol at the University of Colorado. Peripheral blood from healthy subjects was obtained from two sources: an IRB-approved tissue collection protocol at National Jewish Health (Denver, Colorado) and Astarte Biologics (Bothell, WA). Blood samples were processed via mononuclear cell enrichment by Ficoll gradient processing and were subsequently cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen.

MDS patient clinical data

Clinical parameters for MDS patients were collected through retrospective chart review and included date of diagnosis, World Health Organization (WHO) subtype [39], revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R) scores [40], treatment history, absolute peripheral blood monocyte count, and for patients diagnosed after 2014, a next-generation targeted resequencing panel analyzing the status of 54 genes (Supplemental Table 1). Next generation sequencing of DNA from bone marrow aspirate using the TruSight myeloid sequencing panel with 568 amplicons interrogating 54 genes was performed with genomic DNA isolated using the Promega Maxwell® RSC Blood DNA Kit (Promega). 100 micrograms of DNA were processed using the TruSight Myeloid Sequencing Panel (Illumina), and the normalized libraries were pooled and loaded onto a MiSeq for sequencing using the 600-cycle MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 to generate 2×250 bp reads. Results of the targeted resequencing are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

Flow cytometry analysis

Immediately after thawing frozen PBMCs, an aliquot of cells was fixed and stained with the following antisera: anti-CD14-FITC (BD Biosciences), anti-CD16-PerCP (Invitrogen), anti-HLA-DR-PE (ebioscience), anti-CD20-PacBlue (Biolegend), and anti-CD15-PacBlue (Biolegend). Isotype-matched antisera were used as negative controls. Samples were analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer running BD FACSDIVATM acquisition software. Data were analyzed using FlowJo. The “non-lymphocyte” gate excludes small lymphocytes as well as dead cells and debris from the thaw. CD15 and CD20 were used to exclude neutrophils and B cells. All samples (healthy volunteers and MDS patients) were collected and treated similarly using identical freezing, thawing, and staining procedures. Fidelity and consistency of analysis were maintained via the batch processing function in FlowJo using exactly the same gates for all sample analyses.

Isolation of monocytes

Monocytes were isolated using a two-step purification protocol. First, frozen PBMCs were thawed in X-Vivo 10 Hematopoietic Cell Medium (Lonza), and monocytes were enriched using a Human Pan Monocyte Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Enriched monocytes were counted using a hemocytometer and were further purified by plate adherence to tissue culture plastic in X-Vivo 10 medium supplemented with 3% heat inactivated platelet-poor plasma (HIPPP) and 1% Penicilin/Streptomycin (Fisher). HIPPP was produced by pooling platelet-poor plasma from 7 healthy donors, was isolated via Percoll separation and centrifugation, and was provided by Silvia Caceres and Ken Malcolm. Monocytes were plated at 100,000 cells per well in 96-well format. After one hour, the few non-adherent cells were removed by aspiration and adherent monocytes were used as outlined below.

Assaying monocyte response to LPS

Adherent monocytes (100,000 cells per well in 96-well format) were exposed to 20 ng/ml LPS (List Biological Labs) in X-Vivo 10 medium supplemented with 3% HIPPP and 1% Pen/Strep for four hours. After four hours, supernatants were collected and cytokine protein production (TNFα and IL-6) was monitored by ELISA (R&D Biosystems). RNA for qPCR analysis was prepared by lysing the adherent cells in RLT buffer (Qiagen) and using the Qiagen RNAeasy kit for RNA purification. qPCR was performed using the Qiagen Quantitect SYBR-Green RT-PCR kit and an ABI 7900 Thermocycler. Data were normalized relative to βactin using the ddCt method. Primer sequences used for qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

Assaying monocyte phagocytosis

The ability of adherent monocytes to phagocytose FITC-labeled E. coli was monitored using a BioTek Synergy HT plate reader and the Vybrant Phagocytosis assay Kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Methods and limitations

To allow for comparison between experiments, the ELISA, qPCR, and phagocytosis data were all assayed relative to a common untreated control sample; these data were in turn normalized so that the healthy volunteers averaged to 1. The range of cytokine values in the ELISA data for healthy donors was 890 ± 510 pg/ml (avg ± stdev) for IL-6 and 540 ± 480 pg/ml (avg ± stdev) for TNFα. The qPCR data is all relative quantitation (ddCt method), and phagocytosis is assayed in arbitrary fluorescence units. All data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism 5. Unpaired t-tests were used to test for statistically significant differences in the flow cytometry data. Statistical analyses comparing data from MDS patients and healthy volunteers were performed using one-way Anova. To explore the association between monocyte function and clinical factors in MDS patients, single variable linear regression was used to test for association between these clinical factors and monocyte function. Statistical significance was considered P < 0.05.

One limitation to this study is that we do not have access to unfrozen monocytes for analysis. We did observe some loss of viability of frozen cells; however, cell recovery did not correlate with the monocyte population distribution, HLA-DR levels, or LPS-induced cytokine production, suggesting that the use of frozen samples does not account for the comparisons between healthy subjects and MDS patients.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Monocytes from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) exhibit significant immune dysfunction including an altered monocyte profile and a diminished inflammatory response induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [33–35]. To determine if monocytes from MDS patients exhibit similar dysfunction, we analyzed monocyte function from the peripheral blood of 43 patients with MDS (27 untreated and 16 treated) and 14 healthy control subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Control | MDS untreated | MDS treated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 14 | 27 | 16 |

| Agea | 60.9 ± 6.5 | 65.8 ± 12.1 | 68.8 ± 8.5 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 8 | 12 | 7 |

| Male | 6 | 15 | 9 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 14 | 24 | 15 |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Treatment | |||

| Azacitidine | n/a | n/a | 9 |

| Decitabine | n/a | n/a | 2 |

| Lenalidomide | n/a | n/a | 2 |

| Multiple | n/a | n/a | 3 |

| Selective Disease Features | |||

| High grade MDSb | n/a | 2 | 4 |

| Treatment Related MDS | n/a | 3 | 1 |

| del5q MDS | n/a | 1 | 0 |

| IPSS-R Risk Categories | |||

| Low (≤3) | n/a | 13 | 3 |

| Intermediate (>3–4.5) | n/a | 4 | 7 |

| High (>4.5) | n/a | 10 | 6 |

Age displayed as mean ± stdev

Blasts account for 5–19% of marrow cells and/or 3–19% of blood cells

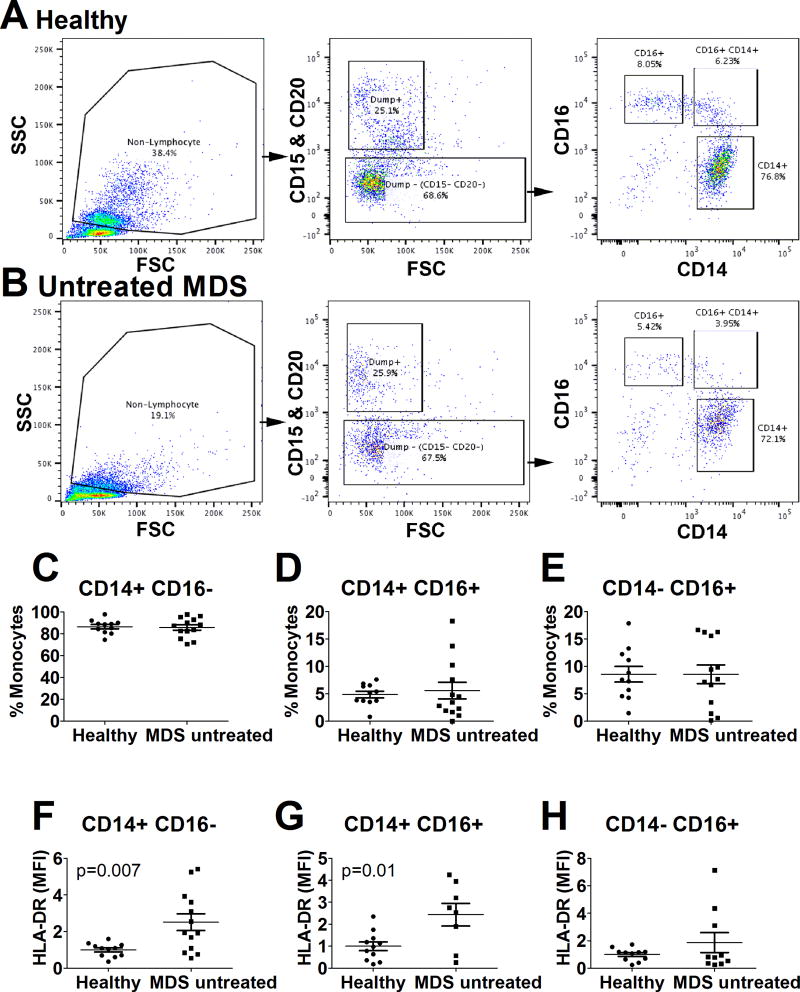

To determine if the monocyte composition in peripheral blood was altered in MDS patients, we used flow cytometry to analyze CD14 and CD16 expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from untreated MDS patients and age-matched healthy blood donors. We found that the frequency of classical (CD14+ CD16−), intermediate (CD14+ CD16+), and non-classical (CD14− CD16+) monocytes was not altered in untreated MDS patients compared to healthy donors (Figure 1A–E). This is quite different from monocytes in CLL patients, where the non-classical monocyte population is significantly increased [33, 34]. We did observe a significant increase in HLA-DR expression in the classical and intermediate monocyte subsets in the untreated MDS patients (Figure 1F–H); this finding also differs from monocytes isolated from CLL patients, which exhibit moderately decreased HLA-DR expression [33].

Figure 1. Normal composition of monocyte subsets in MDS patients.

Immediately after thawing frozen PBMCs from either healthy volunteers or from untreated patients with MDS, an aliquot of cells was fixed and subsequently stained for flow cytometry analysis. An identical gating strategy using FlowJo batch processing was used to analyze monocyte subsets in all samples. Small lymphocytes and dead cells were omitted from the initial cell gate (“non-lymphocytes”); then cells with high CD15 or CD20 were removed using a dump channel strategy; and finally CD14 and CD16 levels were assayed. Representative examples of this gating strategy are displayed for a healthy volunteer (A) and an untreated MDS patient (B). Panels C–E display the frequency of monocyte subsets. Panels F–H display HLA-DR levels (MFI) normalized relative to control in each of the three monocyte subsets (average of control defined as 1). Those comparisons that were significantly different have P values listed; all other comparisons were not significant.

Monocytes have multiple key functions in the immune system, including the secretion of cytokines in response to immune challenge and phagocytosis of bacteria. We monitored these functions in monocytes isolated from MDS patients to determine if they exhibit immune defects. Monocytes from healthy blood donors, untreated MDS patients, or treated MDS patients were first enriched from PBMCs using a Human Pan Monocyte Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) and then further purified by plate adherence to tissue culture plastic. After one hour, the few remaining non-adherent cells were removed, and the percentage of monocytes in the enriched cell population was then checked by flow cytometry.

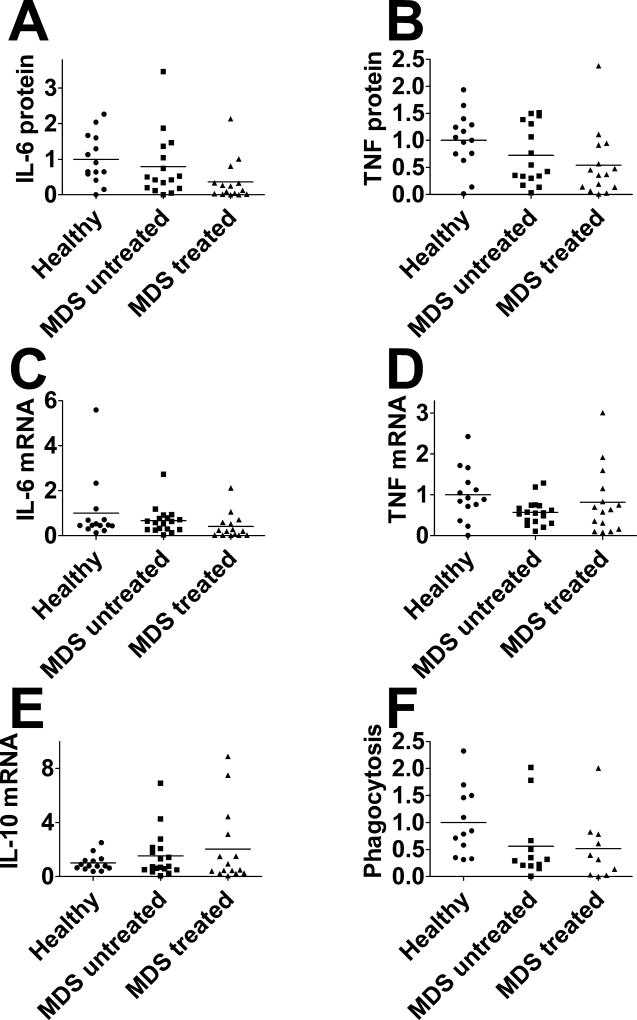

The production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 20 ng/ml for 4 hours) was measured at the protein level by ELISA and at the mRNA level by qPCR. TNFα or IL-6 protein production induced by LPS was not significantly altered in monocytes from MDS patients, regardless of treatment status (Figure 2A,B). Likewise, TNFα or IL-6 mRNA levels did not differ in MDS patients compared to healthy control subjects, regardless of treatment status (Figure 2C,D). The level of mRNA for the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 also was similar among these three groups (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. Monocytes from MDS patients do not exhibit significant immune defects.

Monocytes from either healthy volunteers, untreated MDS patients, or treated MDS patients were exposed to 20 ng/ml LPS for four hours and production of the indicated cytokine proteins (A,B) or mRNAs (C–E) was monitored. (F) Monocytes were incubated for two hours with fluorescently labeled E. coli particles and phagocytosis of these fluorescent particles was monitored using the Vybrant Phagocytosis assay Kit (Molecular Probes). All values normalized so that healthy volunteer data is averages to 1. None of the monitored parameters were statistically different from each other as determined by one-way Anova.

We also monitored uptake of fluorescently labeled bacteria. Phagocytosis of fluorescent E. coli particles was similar in monocytes isolated from untreated MDS patients, treated MDS patients, and healthy control subjects (Figure 2F).

Thus, our data indicate that there was little or no difference in some basic monocyte functions (LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine production and phagocytosis) in either treated or untreated MDS patients compared to healthy subjects of a similar age. This is a distinct finding from monocytes from CLL patients, which exhibit significant immune deficits [33], and also contrasts with the strong immune dysfunction present in neutrophils from MDS patients [15, 17]. This may help explain why some MDS patients with neutropenia or neutrophilic dysfunction do not have significant clinical complications from infection.

We also tested if clinical parameters in MDS patients affect monocyte function, focusing on untreated MDS patients to remove variability due to differences in treatment strategies. Clinical parameters for MDS patients were collected through retrospective chart review and included date of diagnosis, World Health Organization subtype [39], revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R) scores [40], treatment history, absolute peripheral blood monocyte count, and number of mutations present.

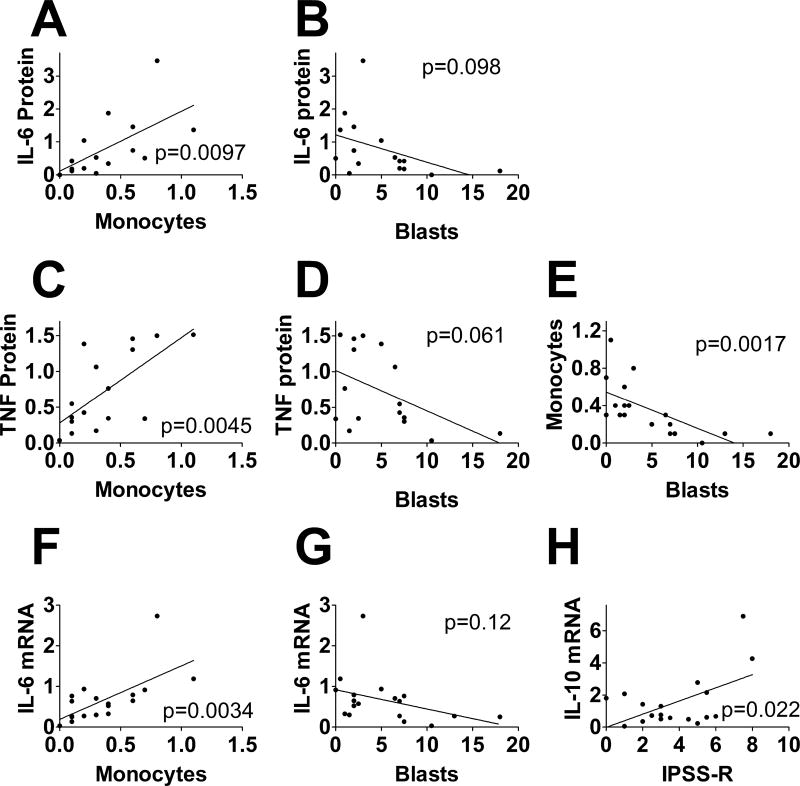

LPS-induced IL-6 and TNFα protein production were both strongly positively associated with absolute peripheral blood monocyte count (Figure 3A,C), suggesting that patients producing higher levels of monocytes in their blood also produce monocytes that are more responsive to LPS. While not statistically significant, we also noted a trend towards an inverse correlation between bone marrow blast percentage and LPS-induced IL-6 and TNFα protein production (Figure 3B,D). These inverse associations between cytokine production and either marrow blasts or peripheral blood monocyte counts were consistent with our observation that marrow blast percentage and peripheral blood monocyte counts were inversely associated in untreated MDS patients (Figure 3E). In contrast to the association between cytokine production observed with monocyte count and the trend towards an association with blast percentage, IL-6 or TNFα protein levels were not associated with either IPSS-R score or with the number of mutations present (Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 3. Association of clinical factors with monocyte function in patients with MDS.

The graphs display the indicated cytokine proteins (A–D) or cytokine mRNAs (F–H) produced by monocytes (from untreated MDS patients) challenged with 20 ng/ml LPS for four hours compared to the indicated clinical factors in these patients (absolute peripheral blood monocyte count, marrow blast cell percentage, or IPSS-R score). Panel E depicts a comparison of absolute peripheral blood monocyte count and marrow blast cell percentage in these same patients. Solid lines depict the predicted variables from single variable linear regression. The p values from these analyses also are indicated. Further statistical information relevant to this figure is presented in Supplemental Table 4.

The association between IL-6 and peripheral blood monocyte count also extended to the mRNA level, as IL-6 mRNA levels were strongly positively associated with peripheral blood monocyte count (Figure 3F) and trended towards an inverse association with marrow blast cell percentage (Figure 3G). Consistent with the protein data, IL-6 mRNA was not associated with IPSS-R score or mutation count (Supplemental Table 4). Interestingly, TNFα mRNA was not associated with any of these four clinical parameters (Supplemental Table 4). In contrast, IL-10 mRNA levels were positively associated with IPSS-R score (Figure 3H) but not the other parameters (Supplemental Table 4). We also found that phagocytic ability of monocytes isolated from untreated MDS patients did not significantly associate with any of the four clinical factors tested (Supplemental Table 4). These associations indicate that MDS clinical parameters may affect monocyte function in these patients.

In conclusion, we find that monocyte composition, monocyte LPS response, and monocyte phagocytic ability are relatively unchanged in peripheral blood from patients with MDS. A prior study [37] indicated that monocytes from MDS patients exhibit an increased response to CD40 activation. Coupled with the increased MHC Class II production observed in the current study, this may suggest that the enhanced ability to present antigen and activate T cells could compensate, at least in part, for decreased neutrophil function present in these patients. Such a possibility should be examined in a larger study that examines several of these immune cell populations simultaneously. We also note that we have only analyzed a subset of monocyte functions, and it is possible that other monocyte functions may be altered in these patients. However, overall we find that, surprisingly, monocytes from MDS patients in the peripheral blood do not have gross immune deficits, and thus may contribute to fighting infection in these patients. Future large prospective clinical studies correlating monocyte number or function with infectious complications should be considered.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

Monocytes from patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome exhibit relatively normal immune function and could contribute to infection control in these patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 1R01ES025161 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) as well as grants from the Cancer League of Colorado, the University of Colorado Hematology Division, and the Wendy Siegel Fund for Leukemia and Cancer Research. We thank Silvia Caceres and Ken Malcolm for supplying HIPPP.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- HLA-DR

Human Leukocyte Antigen – antigen D Related

- IPSS-R

Revised International Prognostic Scoring System

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MDS

Myelodysplastic Syndrome

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Authorship: D.A.P. analyzed data and helped write the manuscript. B.R.H. performed experiments, analyzed data, and helped write the manuscript. B.P.O. analyzed data and helped write the manuscript. S.A. analyzed data and helped write the manuscript.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:1872–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barzi A, Sekeres MA. Myelodysplastic syndromes: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77:37–44. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2011 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. American journal of hematology. 2011;86:490–8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corey SJ, Minden MD, Barber DL, Kantarjian H, Wang JC, Schimmer AD. Myelodysplastic syndromes: the complexity of stem-cell diseases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:118–29. doi: 10.1038/nrc2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sekeres MA. The epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2010;24:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma X, Does M, Raza A, Mayne ST. Myelodysplastic syndromes: incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007;109:1536–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dayyani F, Conley AP, Strom SS, Stevenson W, Cortes JE, Borthakur G, Faderl S, O'Brien S, Pierce S, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G. Cause of death in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2010;116:2174–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg SL, Chen E, Corral M, Guo A, Mody-Patel N, Pecora AL, Laouri M. Incidence and clinical complications of myelodysplastic syndromes among United States Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:2847–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nachtkamp K, Stark R, Strupp C, Kundgen A, Giagounidis A, Aul C, Hildebrandt B, Haas R, Gattermann N, Germing U. Causes of death in 2877 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Annals of hematology. 2016;95:937–44. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2649-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oguma S, Yoshida Y, Uchino H, Okuma M, Maekawa T, Nomura T. Infection in myelodysplastic syndromes before evolution into acute non-lymphoblastic leukemia. International journal of hematology. 1994;60:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagano L, Caira M. Risks for infection in patients with myelodysplasia and acute leukemia. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2012;25:612–8. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328358b000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pomeroy C, Oken MM, Rydell RE, Filice GA. Infection in the myelodysplastic syndromes. The American journal of medicine. 1991;90:338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan LR, Sekeres MA, Shrestha NK, Maciejewski JP, Tiu RV, Butler R, Mossad SB. Epidemiology and risk factors for infections in myelodysplastic syndromes. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2013;15:652–7. doi: 10.1111/tid.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toma A, Fenaux P, Dreyfus F, Cordonnier C. Infections in myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 2012;97:1459–70. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.063420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boogaerts MA, Nelissen V, Roelant C, Goossens W. Blood neutrophil function in primary myelodysplastic syndromes. British journal of haematology. 1983;55:217–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1983.tb01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breton-Gorius J, Houssay D, Dreyfus B. Partial myeloperoxidase deficiency in a case of preleukaemia. I. Studies of fine structure and peroxidase synthesis of promyelocytes. British journal of haematology. 1975;30:273–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1975.tb00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fianchi L, Leone G, Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Guidi F, Valentini CG, Voso MT, Pagano L. Impaired bactericidal and fungicidal activities of neutrophils in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia research. 2012;36:331–3. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koeffler HP. Myelodysplastic syndromes (preleukemia) Seminars in hematology. 1986;23:284–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin S, Baldock SC, Ghoneim AT, Child JA. Defective neutrophil function and microbicidal mechanisms in the myelodysplastic disorders. Journal of clinical pathology. 1983;36:1120–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.10.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mewawalla P, Dasanu CA. Immune alterations in untreated and treated myelodysplastic syndrome. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2011;10:351–61. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2011.534456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prodan M, Tulissi P, Perticarari S, Presani G, Franzin F, Pussini E, Pozzato G. Flow cytometric assay for the evaluation of phagocytosis and oxidative burst of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes in myelodysplastic disorders. Haematologica. 1995;80:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruutu P, Ruutu T, Repo H, Vuopio P, Timonen T, Kosunen TU, de la Chapelle A. Defective neutrophil migration in monosomy-7. Blood. 1981;58:739–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruutu P, Ruutu T, Vuopie P, Kosunen TU, de la Chapelle A. Defective chemotaxis in monosomy-7. Nature. 1977;265:146–7. doi: 10.1038/265146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruutu P, Ruutu T, Vuopio P, Kosunen TU, de la Chapelle A. Function of neutrophils in preleukaemia. Scandinavian journal of haematology. 1977;18:317–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1977.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caira M, Latagliata R, Girmenia C. The risk of infections in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes in 2016. Expert review of hematology. 2016;9:607–14. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2016.1181540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falantes JF, Calderon C, Marquez-Malaver FJ, Aguilar-Guisado M, Martin-Pena A, Martino ML, Montero I, Gonzalez J, Parody R, Perez-Simon JA, Espigado I. Patterns of infection in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia receiving azacitidine as salvage therapy. Implications for primary antifungal prophylaxis. Clinical lymphoma, myeloma & leukemia. 2014;14:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voso MT, Niscola P, Piciocchi A, Fianchi L, Maurillo L, Musto P, Pagano L, Mansueto G, Criscuolo M, Aloe-Spiriti MA, Buccisano F, Venditti A, Tendas A, Piccioni AL, Zini G, Latagliata R, Filardi N, Fragasso A, Fenu S, Breccia M, Grom, Basilicata MDSR. Standard dose and prolonged administration of azacitidine are associated with improved efficacy in a real-world group of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or low blast count acute myeloid leukemia. European journal of haematology. 2016;96:344–51. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williamson PJ, Oscier DG, Mufti GJ, Hamblin TJ. Pyogenic abscesses in the myelodysplastic syndrome. Bmj. 1989;299:375–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6695.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bieber K, Autenrieth SE. Insights how monocytes and dendritic cells contribute and regulate immune defense against microbial pathogens. Immunobiology. 2015;220:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews T, Sullivan KE. Infections in patients with inherited defects in phagocytic function. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2003;16:597–621. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.597-621.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deinard AS, Geehan G, Page AR, Holmes B. Function studies of monocytes from patients with cyclic neutropenia. The American journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 1980;2:201–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenwood MF, Jones EA, Jr, Holland P. Monocyte functional capacity in chronic neutropenia. American journal of diseases of children. 1978;132:131–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120270029005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurado-Camino T, Cordoba R, Esteban-Burgos L, Hernandez-Jimenez E, Toledano V, Hernandez-Rivas JA, Ruiz-Sainz E, Cobo T, Siliceo M, Perez de Diego R, Belda C, Cubillos-Zapata C, Lopez-Collazo E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a paradigm of innate immune cross-tolerance. Journal of immunology. 2015;194:719–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maffei R, Bulgarelli J, Fiorcari S, Bertoncelli L, Martinelli S, Guarnotta C, Castelli I, Deaglio S, Debbia G, De Biasi S, Bonacorsi G, Zucchini P, Narni F, Tripodo C, Luppi M, Cossarizza A, Marasca R. The monocytic population in chronic lymphocytic leukemia shows altered composition and deregulation of genes involved in phagocytosis and inflammation. Haematologica. 2013;98:1115–23. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.073080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soares-Schanoski A, Jurado T, Cordoba R, Siliceo M, Fresno CD, Gomez-Pina V, Toledano V, Vallejo-Cremades MT, Alfonso-Iniguez S, Carballo-Palos A, Fernandez-Ruiz I, Cubillas-Zapata C, Biswas SK, Arnalich F, Garcia-Rio F, Lopez-Collazo E. Impaired antigen presentation and potent phagocytic activity identifying tumor-tolerant human monocytes. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;423:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maurer AB, Ganser A, Buhl R, Seipelt G, Ottmann OG, Mentzel U, Geissler RG, Hoelzer D. Restoration of impaired cytokine secretion from monocytes of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes after in vivo treatment with GM-CSF or IL-3. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 1993;7:1728–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meers S, Kasran A, Boon L, Lemmens J, Ravoet C, Boogaerts M, Verhoef G, Verfaillie C, Delforge M. Monocytes are activated in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and can contribute to bone marrow failure through CD40–CD40L interactions with T helper cells. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2007;21:2411–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt CS, Aranda Lopez P, Dopheide JF, Schmidt F, Theobald M, Schild H, Lauinger-Lorsch E, Nolte F, Radsak MP. Phenotypic and functional characterization of neutrophils and monocytes from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome by flow cytometry. Cellular immunology. 2016;308:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, Sanz G, Garcia-Manero G, Sole F, Bennett JM, Bowen D, Fenaux P, Dreyfus F, Kantarjian H, Kuendgen A, Levis A, Malcovati L, Cazzola M, Cermak J, Fonatsch C, Le Beau MM, Slovak ML, Krieger O, Luebbert M, Maciejewski J, Magalhaes SM, Miyazaki Y, Pfeilstocker M, Sekeres M, Sperr WR, Stauder R, Tauro S, Valent P, Vallespi T, van de Loosdrecht AA, Germing U, Haase D. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:2454–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.