Abstract

Objective

DNA methylation has been associated with both early life stress and depression. This study examined the combined association of DNA methylation at multiple CpG probes in five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms, and tested whether these genes methylation mediated the association between childhood trauma and depression in two monozygotic (MZ) twin studies.

Methods

The current analysis comprised 119 MZ twin pairs (84 male pairs [mean 55 years], and 35 female pairs [mean 36 years]). Peripheral blood DNA methylation of five stress-related genes (BDNF, NR3C1, SLC6A4, MAOA, and MAOB) was quantified by bisulfite pyrosequencing or 450K BeadChip. We applied generalized Poisson linear mixed models to examine the association between each single CpG methylation and depressive symptoms. The joint associations of multiple CpGs in a single gene or all five stress-related genes as a pathway were tested by weighted truncated product method. Mediation analysis was conducted to test the potential mediating effect of stress gene methylation on the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms.

Results

Multiple CpG probes showed nominal individual associations, but very few survived multiple testing. Gene-based or gene-set approach, however, revealed significant joint associations of DNA methylation in all five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms in both studies. Moreover, two CpG probes in the BDNF and NR3C1 mediated ~20% of the association between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

DNA methylation at multiple CpG sites are jointly associated with depressive symptoms, and partly mediates the association between childhood trauma and depression. Our results highlight the importance of testing the combined effects of multiple CpG loci on complex traits, and may unravel a molecular mechanism through which adverse early life experiences are biologically embedded.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, DNA methylation, Depression, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis, Mediation analysis, Monozygotic twins

INTRODUCTION

Depression affects over 350 million people worldwide and has been projected to be the second leading cause of disability by the year 2020.1 Exposure to adverse early life experiences such as childhood trauma significantly increases the risk of major depression in adulthood,2 but the molecular mechanisms through which stressful early life events become biologically embedded remain poorly understood. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms through which early life adversity exerts its long-term effect is likely to provide novel insights into disease pathogenesis and may also identify novel therapeutic targets for this debilitating disorder and its related conditions.

DNA methylation, a molecular modification that alters gene expression without changing DNA sequence, can be modified by stressful and socioenvironmental factors,3 and aberrant DNA methylation has been associated with a variety of stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression,4–7 schizophrenia,8 bipolar disorder,9 and autism.10 Thus, DNA methylation may provide a mechanism through which early life adversity becomes biologically embedded in mental illness. Indeed, accumulating evidence from both experimental and human studies has suggested that adverse childhood experience can induce significant and persistent changes in DNA methylation11 and other epigenetic modifications.12 These stress-induced epigenetic alterations can cause stable changes in the expression of genes involved in the stress regulation system, thereby contributing to neuropsychiatric diseases including depression.13

Several candidate genes, including glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), serotonin transporter (SLC6A4), and monoamine oxidase (MAOA, MAOB), are involved in stress response system. Altered DNA methylation of these stress-related genes could impair the negative feedback of HPA-axis,14 and contributes to depression. In support of this hypothesis, altered DNA methylation in the NR3C1,15, 16 BDNF,17–19 and SLC6A420, 21 genes have been associated with depression, possibly through blunting the HPA-axis response to stress.3, 22 Our group has also found that promoter hypermethylation of the SLC6A4 gene was associated with depressive symptoms in a monozygotic twin sample.20 Together, these findings suggest an important role of DNA methylation of stress-related genes in mediating the effect of early life adversity on depression. However, very few studies have tested this mediation in a systematic manner. In addition, previous studies have largely focused on testing the individual effect of single CpG methylation in a candidate gene, but as the effect size of a single CpG methylation could be rather small,23, 24 testing their individual effect on a complex trait would be less efficient. Statistical approaches that can test the combined effect of multiple CpG sites in one gene or multiple genes involved in a biological pathway would be more appropriate.

The objectives of this study are to examine whether DNA methylation of five stress-related genes (NR3C1, SLC6A4, BDNF, MAOA, MAOB) are jointly associated with depressive symptoms, and whether stress-related gene methylation mediates the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and depressive symptoms in two monozygotic (MZ) twin studies.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Twin participants

The Twins Heart Study (THS, discovery sample) was designed to investigate the role of psychological, behavioral, and biological risk factors in subclinical cardiovascular disease using a co-twin control design.25 Briefly, the THS enrolled 187 middle-aged, male twin pairs who were born between 1946 and 1956 from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry (VETR). All twins were free of overt cardiovascular disease at the time of enrollment and were examined in pairs at the Emory University General Clinical Research Center between 2002 and 2010. Zygosity was determined by genotyping. All twins provided written informed consent. The protocol of the THS was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. The current analysis included 84 MZ pairs (n=168) with available DNA sample and phenotype data for both members of a twin pair. Among them, 53 twins had a history of major depression and 35 twins experienced posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The Mood and Methylation Study (MMS, replication sample) is a cross-sectional observational study designed to identify epigenetic determinants of major depression using an MZ discordant twin design. All twins enrolled in the MMS are members of the University of Washington Twin Registry (UWTR), a community-based twin registry consisting of over 10,000 twin pairs.26 The MMS study is currently ongoing and will recruit 150 MZ twin pairs discordant on a lifetime history of major depression. Biospecimen will be collected for each twin and an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) will be conducted using genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood monocytes. The current analysis includes 35 female twin pairs with available DNA methylation and clinical data enrolled between September 2014 and September 2015. All participants provided written informed consent and the study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating Universities. Zygosity was determined using SNP control probes (n = 65) located on the Illumina HumanMethylation450K Beadchip.

Measurement of depressive symptoms

In both studies, current depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).27 The questionnaire includes 21 items and asks how well an individual felt over the past two weeks. Each of the 21 items rates severity of depression on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. Thus, the total score ranges from 0 to 63, with a higher score indicating a higher level of depression. We also measured lifetime history of major depression using the structured clinical interview IV (DSM-IV) in both studies. However, as most twins in the THS experienced their last episode of depression at least 3 years ago, and a different version of the DSM-IV was used in the MMS (DSM-IV-R), the current analysis focused on current depressive symptoms as measured by the continuous BDI-II scores.

Assessment of childhood traumatic experiences

In both THS and MMS, childhood traumatic experiences were assessed retrospectively using the Early Trauma Inventory Self Report - Short Form (ETISR-SF).28 This questionnaire includes 27 true or false questions asking whether an individual was exposed to potentially traumatic experiences before the age of 18. The ETISR-SF assesses four domains of traumatic experiences including physical abuse (5 items), emotional abuse (5 items), sexual abuse (6 items) and general trauma (11 items). Briefly, physical abuse was defined as a physical contact, constraint, or confinement, with intent to hurt or injure. Sexual abuse was defined as an unwanted sexual contact performed solely for the gratification of the perpetrator or for the purposes of dominating or degrading the victim. Emotional abuse captured verbal communication with the intention of humiliating or degrading the victim. General trauma comprised a range of other stressful and traumatic events (i.e., natural disaster, family mental illness, separation of parents etc.). Score on each domain was obtained by summing all items in that domain and further categorized using mean plus one standard deviation (SD) as a cutoff based on the score in healthy individuals without depression or PTSD as previously reported.28 Individuals with a score greater than the cutoff of a specific domain of traumatic experiences were defined as exposed, whereas those with a score less than the cutoff was defined as unexposed to that specific domain of trauma. In addition, we defined a twin as having been exposed to childhood trauma if he/she experienced one or more domains of traumatic experiences and unexposed otherwise. This composite variable was used in the statistical analysis.

DNA methylation measurement

In the THS, promoter DNA methylation of five stress-related genes, including BDNF, NR3C1, SLC6A4, MAOA, and MAOB, was quantified by bisulfite pyrosequencing using genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes. Detailed methods for DNA methylation assays had been described previously.20 In brief, genomic DNA was first bisulfite treated using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Inc., CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and then processed by pyrosequencing on the PSQ96 HS System (Pyrosequencing, Qiagen). For quality control, each experiment included non-CpG cytosines as an internal control to verify completion of sodium bisulfite DNA conversion. Pyrosequencing assay was run in duplicates, with a high correlation (≥ 99.8%) of two runs for the same sample.

In the MMS, DNA methylation of the five candidate genes in peripheral blood monocytes was obtained as a part of the EWAS by Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). In brief, monocytes were isolated from fresh peripheral blood (collected into EDTA vacutainer tubes) using the Monocyte Isolation Kit II from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). Genomic DNA isolated from monocytes was first bisulfite treated using the EZ-96 DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA, USA) and then whole genome widely amplified, fragmented and hybridized to locus-specific oligomer probes linked to individual beads on a BeadChip array. Hybridization was followed by single-base extension of the oligomer with a labeled nucleotide. The BeadChip was subsequently fluorescently stained and scanned on HiScan scanner (Illumina Inc.). Data pre-processing and QC followed manufacturer’s instructions. Twin pairs with one or both samples had >5% of probes with a detection p>0.05 were excluded from downstream analysis. Prior to statistical analysis, DNA methylation data were normalized with functional normalization after subtracting background noises using the R package minfi.29 This method corrects for the bias of the two different probe types on the array and batch effects via an unsupervised approach.30

In both studies, DNA methylation level at each CpG site was calculated as the percentage of the methylated alleles over the sum of methylated and un-methylated alleles, i.e., methylation value ranging from 0 (un-methylated) to 100% (fully methylated). To minimize batch effect, matched twin pairs were hybridized on the same assay or chip. Supplementary Figures S1–S5 schematically illustrate the relative positions of the assayed CpGs in either study.

Other measurements

For both studies, body weight (kg) and height (cm) were measured when twin participants wore light clothes and no shoes by trained research staff. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Pack-years of smoking were calculated as the number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day times the number of years smoked. Physical activity was assessed by means of the Baecke global physical activity score, which summarizes activity related to work, sports, and leisure.31 Family income level in the past year was assessed using a 10-point scale with a higher score indicating higher income. All the measurements were performed at the same moment as blood drawn.

In the THS, information on alcoholic (wine, beer, or cocktail) beverages consumed within a typical week was obtained and alcohol consumption (g/week) was estimated as previously described.32 Alcohol consumption in the MMS was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), which is a 10-item questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization and has been widely used for screening of harmful and dangerous alcohol consumption.33 In the current analysis, we used the summed score of the first three items as an estimation of alcohol consumption among twins participating in the MMS.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to examine the joint association of DNA methylation at multiple CpG probes in five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms, and test whether stress gene methylation mediates the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and depressive symptoms. Analyses were first conducted in the THS, followed by replication in the MMS. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, Cary, North Carolina).

Gene-based and gene-set analysis to test the joint association of multiple CpG methylation in five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms

Prior studies suggested that the effect size of an individual CpG methylation could be rather small.23, 24 Thus, we examined the joint association of DNA methylation at multiple CpG sites in a candidate gene or all five stress-related genes as a pathway with depressive symptoms. To achieve this, we first conducted single CpG association analysis by constructing generalized Poisson linear mixed models, in which depressive symptoms (BDI-II scores) was the dependent variable and DNA methylation level at each CpG probe in a candidate gene was the independent variable, adjusting for twin age, family income, cigarette smoking (pack-year), alcohol consumption, physical activity, BMI, and history of PTSD (y/n). The mixed Poisson model was used here to account for the within twin-pair correlations and the count data of depressive symptoms. Multiple testing was controlled by adjusting for the total number of CpG sites in a candidate gene, and an FDR-adjusted P-value (i.e., q-value) less than 0.1 was considered nominally significant. We also performed co-twin control analysis based on intra-pair differences in DNA methylation or depressive symptoms of two twins in a pair. However, because our sample size is small and the matched pair analysis further halves the sample size, our gene-based and gene-set analyses as described below were based on results from the mixed model analysis.

Based on results from single CpG association analysis, we tested the joint association of DNA methylation at multiple CpG probes in each stress-related gene with depressive symptoms using the weighted truncated product method (wTPM) as previously described.34 This method combines P-values of all CpGs that reaches a pre-selected threshold (e.g., raw P<0.1 in this study) in a gene of interest. The regression coefficient of each individual CpG methylation was included as weights in the wTPM statistic. Multiple testing of the gene-based analysis was controlled by adjusting for the total number of genes tested. The gene-set association analysis was performed similarly by including all genes with a gene-based P<0.1. This method has been evaluated by simulation studies,35 and our group has applied this method to determine the joint effects of genetic variants in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes on diabetes,36 subclinical atherosclerosis,37 kidney function,38 as well as obesity.39 The present study extended this approach to epigenetic analysis.

Of note, due to using two different platforms for DNA methylation assay, the majority of the CpG probes assayed in our discovery and replication samples were not identical. However, this did not prevent us from replicating our results across the two studies because our primary goal is to test the combined rather than individual association of multiple CpGs methylation in all five stress-related genes with depression. As such, our replication in the MMS focused on gene- and pathway-level association analysis.

Testing the association between childhood traumatic experiences and DNA methylation

To examine the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and DNA methylation of stress-related genes, we constructed a linear mixed model in which DNA methylation at each CpG site was the dependent variable and a specific domain of childhood traumatic experiences (e.g., physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, general trauma, separately, as well as childhood trauma) was the independent variable, adjusting for twin age, family income, pack-year, alcohol consumption, physical activity, BMI, and history of PTSD (y/n). Multiple testing was corrected by adjusting for the total number of CpG sites in each candidate gene and q<0.1 was considered nominally significant.

Mediation analysis

This analysis focuses on CpG sites that showed nominally significant associations with both childhood traumatic experiences and depressive symptoms. To test whether DNA methylation mediates the association between childhood traumatic experiences and depressive symptoms, we constructed a series of conditional regression models as described below. Specifically, we tested the following conditions:

The relationship between each domain of traumatic experiences (X) and current depressive symptoms (Y) (Y=βTotX, βTot: total effect);

The relationship between each domain of traumatic experiences (X) and DNA methylation (M) at each CpG site (M1=β1X, M2=β2X, …, Mn=βnX);

The relationship between DNA methylation (M) and depressive symptoms (Y) after controlling for childhood traumatic experiences (X) (Y=β1’M1+β2’M2+…+βn’Mn+βDirX, βDir: direct effect);

We then calculated the mediating effect of each individual CpG site (β1×β1’ for M1 … βn×βn’ for Mn) or total mediation of all CpGs [β1×β1’+β2×β2’+…+βn×βn’] on the association between childhood traumatic experiences and depressive symptoms. All models were fitted by mixed model to account for the within twin pair correlations and adjusted for twin age, family income, cigarette smoking (pack-year), alcohol consumption, physical activity, BMI, and history of PTSD (y/n). The 95% confidence interval of mediating effect was estimated by the Monte Carlo confidence intervals.40

RESULTS

The current analysis comprises 119 MZ twin pairs, including 84 male MZ twin pairs (n=168, mean age 55 years) from the THS (discovery) and 35 female MZ pairs (n=70, mean age 36 years) from the MMS (replication). Childhood trauma is highly prevalent in both studies (57% of the twins in the THS, and 43% of the female twins in the MMS experienced at least one type of early trauma). The characteristics of twin participants according to exposure status of childhood trauma (y/n) are shown in Table 1. Twins exposed to childhood trauma had a significantly higher BDI-II score than those unexposed in both studies (P <0.001). Moreover, exposed twins smoked more cigarettes and had lower physical activity level than unexposed twins in the MMS (all P <0.05). No significant difference was detected for other listed variables between the two groups. The frequency of each domain of childhood traumatic experiences and their associations with depressive symptoms are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of twins according to childhood trauma exposure in the THS and MMS

| Characteristics | THS (84 male pairs)

|

MMS (35 female pairs)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No trauma | Trauma | P* | No trauma | Trauma | P* | |

| No. of participants | 72 | 96 | 40 | 30 | ||

| Age, years | 54.6±2.5 | 54.7±3.1 | 0.970 | 34.4±13.6 | 39.1±16.5 | 0.731 |

| Family income level | 7.1±2.2 | 6.4±2.4 | 0.073 | 5.0±4.2 | 4.2±4.3 | 0.566 |

| Cigarette smoking, pack-year | 18.9±21.1 | 25.9±25.8 | 0.202 | 1.4±6.9 | 4.9±12.9 | 0.023 |

| Alcohol consumption† | 13.5±48.3 | 11.7±23.8 | 0.791 | 3.3±2.7 | 3.5±2.6 | 0.517 |

| Physical activity score | 7.6±1.8 | 7.2±2.1 | 0.433 | 7.2±1.5 | 6.3±1.9 | 0.014 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.25±4.26 | 29.5±5.21 | 0.758 | 24.25±6.73 | 27.27±6.43 | 0.110 |

| BDI-II score | 4.3±6.7 | 8.4±8.5 | <0.001 | 3.7±3.8 | 8.9±6.7 | <0.001 |

Linear mixed model was used to account for intra-pair correlations of twins.

Alcohol consumption was defined as alcohol consumed per week (g/week) in the THS but as AUDIT score (the first three items) in the MMS.

Trauma was defined as having any types of childhood traumatic experiences including physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and general trauma.

THS: the Twin Heart Study; MMS: the Mood and Methylation Study; BDI-II: the Beck Depression Inventory-II.

Joint association of DNA methylation in five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms

Of the 69 assayed CpG probes in the promoter regions of five stress-related genes assayed in the THS, DNA methylation levels at 27 CpG sites (3 in the BDNF gene, 9 in the NR3C1 gene, 10 in the SLC6A4 gene, 4 in the MAOA gene, 1 in the MAOB gene) appeared to be associated with depressive symptoms after adjusting for covariates (all P<0.05). However, after further correction for multiple testing, 18 CpG sites (2 in the BDNF gene, 9 in the NR3C1 gene, 3 in the SLC6A4 gene, 4 in the MAOA gene) only showed nominal associations at q<0.1 (Table 2). While most putative CpGs in the BDNF, NR3C1, and SLC6A4 genes were positively associated with depressive symptoms (i.e., hypermethylated), we also observed negative associations at 1 CpG in the BDNF gene and 3 CpGs in the NR3C1 gene. In contrast, all CpG sites in the MAOA gene were negatively associated with depressive symptoms (i.e., hypomethylated). Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 show the results of the association between single CpG methylation and depressive symptoms in the THS and MMS, respectively.

Table 2.

Association of single CpG methylation in five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms in the THS (raw P<0.05)

| Genomic position | Relative to TSS (bp) | Methylation level (%, mean±SD) | Depressive symptoms

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE)* | P† | q | |||

| BDNF (Chr11) | |||||

| 27743648 | −1322 | 1.86±1.01 | 0.123 (0.052) | 0.019 | 0.097 |

| 27743651 | −1325 | 4.78±1.20 | 0.223 (0.051) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| 27743673 | −1347 | 3.99±1.96 | −0.071 (0.033) | 0.031 | 0.104 |

| NR3C1 (Chr5) | |||||

| 142783531 | −277 | 3.25±1.59 | 0.120 (0.039) | 0.002 | 0.016 |

| 142783547 | −293 | 1.62±1.55 | 0.097 (0.036) | 0.008 | 0.039 |

| 142783569 | −315 | 3.23±1.48 | 0.147 (0.051) | 0.004 | 0.027 |

| 142783627 | −373 | 0.52±1.39 | −0.101 (0.042) | 0.016 | 0.067 |

| 142783637 | −383 | 0.84±1.60 | 0.069 (0.030) | 0.022 | 0.070 |

| 142783663 | −409 | 0.68±1.52 | −0.083 (0.038) | 0.029 | 0.080 |

| 142783685 | −431 | 0.38±0.99 | 0.100 (0.043) | 0.020 | 0.070 |

| 142783712 | −458 | 1.28±1.58 | −0.220 (0.038) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| 142783730 | −476 | 2.29±2.89 | 0.078 (0.018) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| SLC6A4 (Chr17) | |||||

| 28563002 | −48 | 15.98±7.78 | 0.017 (0.008) | 0.040 | 0.100 |

| 28563016 | −62 | 14.76±6.83 | 0.019 (0.009) | 0.042 | 0.100 |

| 28563020 | −66 | 15.67±4.61 | 0.029 (0.013) | 0.029 | 0.100 |

| 28563054 | −100 | 13.54±5.78 | 0.022 (0.011) | 0.046 | 0.100 |

| 28563101 | −147 | 16.72±7.18 | 0.020 (0.008) | 0.014 | 0.092 |

| 28563106 | −152 | 9.23±3.48 | 0.047 (0.021) | 0.023 | 0.100 |

| 28563108 | −154 | 11.65±4.86 | 0.058 (0.014) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 28563119 | −165 | 11.28±4.06 | 0.031 (0.016) | 0.050 | 0.100 |

| 28563138 | −184 | 13.27±5.57 | 0.034 (0.012) | 0.006 | 0.062 |

| 28563174 | −220 | 3.39±1.91 | −0.073 (0.034) | 0.032 | 0.100 |

| MAOA (ChrX) | |||||

| 43515402 | −65 | 3.70±1.83 | −0.066 (0.030) | 0.028 | 0.049 |

| 43515412 | −55 | 3.73±1.61 | −0.082 (0.037) | 0.027 | 0.049 |

| 43515444 | −23 | 7.24±1.84 | −0.067 (0.030) | 0.024 | 0.049 |

| 43515467 | 1 | 4.67±1.93 | −0.075 (0.032) | 0.020 | 0.049 |

| MAOB (ChrX) | |||||

| 43741815 | −122 | 46.08±8.87 | 0.013 (0.005) | 0.016 | 0.113 |

Change in BDI-II score per 1%-increment of DNA methylation.

Adjusted for twin age, family income level, pack-year, alcohol consumption, physical activity, body mass index, and history of PTSD.

TSS: transcription start site.

Gene-based analysis in the THS detected significant associations of DNA methylation in all five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms after multiple testing correction (all q<0.05), and all these associations were confirmed in the MMS. Gene-set analysis demonstrated that DNA methylation of the stress response pathway jointly contributed to depressive symptoms in both studies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Gene-based and gene-set associations of five stress-related genes methylation with depressive symptoms in the THS and MMS

| Genes | THS

|

MMS

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw P | q | Raw P | q | |

| Gene-based association analysis | ||||

| BDNF | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| NR3C1 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| SLC6A4 | 0.0090 | 0.0150 | 0.0035 | 0.0035 |

| MAOA | 0.0221 | 0.0273 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| MAOB | 0.0273 | 0.0273 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Gene-set association analysis | ||||

| Stress response pathway | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||

THS: the Twin Heart Study; MMS: the Mood and Methylation Study.

Association between childhood trauma and DNA methylation

Supplementary Table S5 presents the association of each domain of childhood traumatic experiences with DNA methylation in five stress-related genes in the THS. It shows that altered DNA methylation of the BDNF gene (hypermethylation at 2 CpG sites, hypomethylation at 1 CpG site) and the NR3C1 gene (hypermethylation at 4 CpG sites) was nominally associated with history of childhood physical abuse (all q <0.1, Table 4). Of these, hypermethylation at 2 CpG sites (1 in the BDNF gene, 1 in the NR3C1 gene) was also nominally associated with depressive symptoms (Table 2). With respect to the composite variable for childhood trauma (y/n), exposure to one or more domains of childhood traumatic experiences was nominally associated with hypermethylation of 10 CpG sites (3 in the BDNF gene, 5 in the NR3C1 gene, 1 in the SLC6A4 gene, 1 in the MAOB gene) (all q <0.1, Table 4). Of these, hypermethylation of 4 CpGs (2 in the BDNF gene and 2 in the NR3C1 gene) was also nominally associated with depressive symptoms (Table 2).

Table 4.

Associations of childhood traumatic experiences with single CpG methylation in five stress-related genes in the THS (raw P<0.05)

| Genomic position | Relative to TSS (bp) | Physical abuse

|

Emotional abuse

|

Sexual abuse

|

General trauma

|

Childhood trauma

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β* | P† | q | β* | P† | q | β* | P† | q | β* | P† | q | β* | P† | q | ||

| BDNF (Chr11) | ||||||||||||||||

| 27743642 | −1316 | 0.621 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.107 | 0.640 | 0.799 | 0.409 | 0.152 | 0.508 | −0.180 | 0.369 | 0.854 | 0.315 | 0.100 | 0.250 |

| 27743648 | −1322 | 0.444 | 0.011 | 0.038 | 0.365 | 0.065 | 0.652 | 0.407 | 0.103 | 0.508 | 0.117 | 0.513 | 0.854 | 0.528 | 0.002 | 0.016 |

| 27743651 | −1325 | 0.419 | 0.041 | 0.103 | 0.209 | 0.383 | 0.799 | 0.503 | 0.093 | 0.508 | 0.109 | 0.605 | 0.864 | 0.500 | 0.013 | 0.063 |

| 27743664 | −1338 | −0.825 | 0.011 | 0.038 | −0.061 | 0.871 | 0.962 | 0.403 | 0.392 | 0.809 | −0.027 | 0.935 | 0.962 | 0.315 | 0.324 | 0.462 |

| 27743673 | −1347 | −0.669 | 0.062 | 0.125 | −0.503 | 0.226 | 0.754 | 0.062 | 0.906 | 0.906 | −0.344 | 0.348 | 0.854 | −0.029 | 0.934 | 0.934 |

| 27743679 | −1353 | 0.064 | 0.835 | 0.835 | −0.017 | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.264 | 0.546 | 0.809 | 0.277 | 0.371 | 0.854 | 0.648 | 0.028 | 0.093 |

| NR3C1 (Chr5) | ||||||||||||||||

| 142783531 | −277 | 0.363 | 0.203 | 0.338 | 0.379 | 0.256 | 0.634 | 0.316 | 0.451 | 0.842 | 0.522 | 0.074 | 0.433 | 0.716 | 0.011 | 0.087 |

| 142783637 | −383 | 0.592 | 0.043 | 0.153 | 0.300 | 0.371 | 0.774 | −0.107 | 0.800 | 0.868 | 0.002 | 0.994 | 0.997 | 0.566 | 0.048 | 0.171 |

| 142783655 | −401 | 0.521 | 0.041 | 0.153 | 0.486 | 0.096 | 0.578 | −0.100 | 0.786 | 0.868 | 0.485 | 0.063 | 0.433 | 0.589 | 0.018 | 0.090 |

| 142783678 | −424 | 0.649 | 0.039 | 0.153 | 0.276 | 0.458 | 0.817 | −0.231 | 0.621 | 0.868 | −0.227 | 0.486 | 0.675 | 0.306 | 0.330 | 0.434 |

| 142783685 | −431 | 0.451 | 0.011 | 0.067 | 0.266 | 0.191 | 0.634 | 0.099 | 0.699 | 0.868 | 0.187 | 0.304 | 0.501 | 0.381 | 0.028 | 0.118 |

| 142783688 | −434 | 0.629 | 0.004 | 0.034 | 0.590 | 0.019 | 0.156 | 0.647 | 0.041 | 0.516 | 0.303 | 0.181 | 0.453 | 0.618 | 0.004 | 0.087 |

| 142783702 | −448 | 1.567 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.377 | 0.403 | 0.774 | 1.166 | 0.041 | 0.516 | 0.583 | 0.148 | 0.453 | 0.939 | 0.014 | 0.088 |

| 142783716 | −462 | 1.022 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.432 | 0.279 | 0.634 | 0.773 | 0.127 | 0.791 | 0.334 | 0.350 | 0.515 | 0.445 | 0.193 | 0.322 |

| 142783730 | −476 | 0.793 | 0.124 | 0.333 | 0.182 | 0.758 | 0.874 | 0.587 | 0.430 | 0.842 | 1.058 | 0.044 | 0.433 | 1.338 | 0.007 | 0.087 |

| 142783742 | −488 | 0.780 | 0.229 | 0.357 | 1.794 | 0.015 | 0.156 | 1.538 | 0.104 | 0.791 | −0.358 | 0.590 | 0.722 | 0.869 | 0.172 | 0.307 |

| SLC6A4 (Chr17) | ||||||||||||||||

| 28563138 | −184 | 2.041 | 0.017 | 0.209 | 0.101 | 0.924 | 0.997 | 0.597 | 0.645 | 0.986 | 1.035 | 0.244 | 0.415 | 0.738 | 0.393 | 0.734 |

| 28563185 | −231 | 0.592 | 0.050 | 0.209 | 0.417 | 0.233 | 0.997 | 0.439 | 0.321 | 0.986 | 0.371 | 0.232 | 0.415 | 0.940 | 0.001 | 0.023 |

| MAOB (ChrX) | ||||||||||||||||

| 43741775 | −82 | 0.944 | 0.409 | 0.762 | 0.662 | 0.625 | 0.983 | 1.129 | 0.502 | 0.502 | 1.992 | 0.089 | 0.620 | 3.875 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| 43741781 | −88 | 0.088 | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.028 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 3.345 | 0.044 | 0.310 | −0.325 | 0.780 | 0.984 | 1.547 | 0.166 | 0.194 |

| 43741785 | −92 | 1.033 | 0.436 | 0.762 | −0.078 | 0.961 | 0.983 | 2.412 | 0.220 | 0.385 | 0.761 | 0.577 | 0.984 | 2.856 | 0.029 | 0.101 |

Increase in methylation level (%) for individuals with versus without the specific type of childhood traumatic experiences.

Adjusted for twin age, family income level, pack-year, alcohol consumption, physical activity, body mass index, and history of PTSD.

TSS: transcription start site.

In addition to the above described CpG sites in response to physical abuse and the composite variable for childhood trauma, we also observed nominal associations of DNA methylation at multiple CpG sites with other domains of childhood traumatic experiences, but none withstood multiple testing correction, probably due to the low prevalence of such events (and thus low statistical power) in our sample.

While we cannot replicate the associations between childhood trauma and DNA methylation of the 10 CpGs identified in the THS due to incomplete overlapping of CpG probes assayed in the two studies, we detected an association between hypermethylation of a CpG probe in the NR3C1 gene and emotional abuse in the MMS (q=0.042). Results of the associations between childhood traumatic experiences and DNA methylation of the five stress-related genes in the MMS are shown in Supplementary Table S6.

DNA methylation of stress-related genes mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms

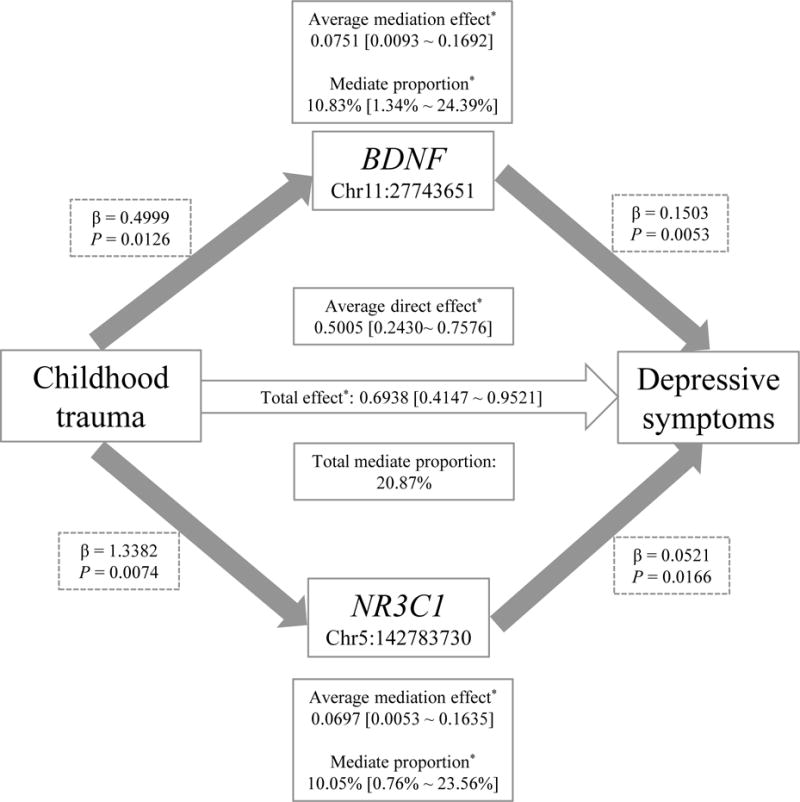

Our mediation analysis focused on 4 CpG loci (2 in the BDNF gene and 2 in the NR3C1 gene) that are nominally associated with both childhood trauma (y/n) and depressive symptoms in the THS. We found that hypermethylation of 3 CpG sites (1 in the BDNF gene, 2 in the NR3C1 gene) showed significant individual mediation on the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms (Table 5). To examine their joint mediating effect, we conducted multiple mediation analysis by including all 3 CpG sites in a single mediation model. We found that 2 CpG sites (1 in the BDNF gene and 1 in the NR3C1 gene) jointly mediated the association between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms. The joint mediating effect of these 2 CpGs was schematically illustrated in Figure 1. DNA methylation of one CpG site in the BDNF gene and one CpG site in the NR3C1 gene accounts for about 11% (95% CI: 1.3% - 24.4%) and 10% (95% CI: 0.8% - 23.6%), respectively, of the association between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms. However, we were unable to replicate these mediating effects in the MMS due to incomplete overlapping of single CpG probes assayed in the two studies.

Table 5.

Individual mediating effect of four single CpG methylation on the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in the THS

| CpG site | Gene | Mediating effect* β (95%CI) |

Mediating proportion % (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chr11:27743648 | BDNF | 0.0472 (−0.0072, 0.1210) | NS |

| Chr11: 27743651 | BDNF | 0.0812 (0.0131, 0.1767) | 11.70 (1.88, 25.46) |

| Chr5: 142783531 | NR3C1 | 0.0667 (0.0046, 0.1577) | 9.61 (0.66, 22.73) |

| Chr5: 142783730 | NR3C1 | 0.0913 (0.0213, 0.1839) | 13.15 (3.07, 26.51) |

The four CpG sites showing nominally significant associations with both childhood trauma and depressive symptoms were included in the mediation model separately.

All analyses adjusted for twin age, family income level, pack-year, alcohol consumption, physical activity, body mass index, and history of PTSD.

NS: statistically nonsignificant.

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the joint mediating effect of two CpGs in the BDNF and NR3C1 genes on the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in the THS. In this model, the three CpG sites showing significant individual mediation were included as mediators, childhood trauma was exposure variable, and depressive symptoms was outcome variable, adjusting for twin age, family income level, pack-year, alcohol consumption, physical activity, body mass index, and history of PTSD. One CpG site in the NR3C1 gene (Chr5: 142783531) showing a significant mediating effect in individual mediation analysis but not in joint mediation analysis was not shown in this figure. *P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In two monozygotic twin studies, we demonstrated for the first time that DNA methylation in five stress-related genes were jointly associated with depressive symptoms, and partially mediated the association between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms at adulthood. Our finding highlights the importance of testing the combined epigenetic effects of multiple CpG loci on human complex traits, and may also unravel a molecular pathway through which adverse early life experiences become biologically embedded in risk of depression later in life.

In line with previous studies,23, 24 we found that the association of an individual CpG methylation with depressive symptoms was in general small (mostly <5%), and statistically most CpG sites could not withstand multiple testing correction. For instance, of the 18 CpG sites showing nominal associations with depressive symptoms at q<0.1 in our discovery sample, except for one CpG in the NR3C1 gene which explains about 6% of variability in depressive symptoms, DNA methylation at all other 17 CpG sites singly explained about 0.04% - 3.5% of the variance in depressive symptoms, and only 8 CpG loci passed multiple testing at the level of q<0.05. A similar phenomenon was also observed in our replication sample. Such small effect size may not be detected by conventional statistical methods. However, their combined effects may be large enough to be useful for risk prediction. For example, of the 7 CpG loci in the MAOB gene assayed in the THS, although DNA methylation at only one site was nominally associated with depressive symptoms (raw P=0.016), which disappeared after multiple testing correction, our gene-based analysis detected a significant association of all 7 CpG probes in this gene with depressive symptoms (q=0.026). Similarly, our gene-set analysis comprising all five stress-related genes illustrated that altered DNA methylation of the stress response pathway as a whole was significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Together, these results demonstrated that testing the combined effects of multiple CpG loci in a gene or multiple candidate genes in a pathway represents a powerful approach to unravel the complex epigenetic etiology of human complex traits such as depression. Of note, although several previous studies have reported associations of single CpG methylation in stress-related genes such as BDNF,17–19, 41 NR3C1,16, 42 SLC6A4,21 and MAOA43 with major depression, no study has systemically tested the joint contribution of multiple CpG methylation in one or multiple genes in the stress response pathway in relation to depression. Moreover, we are unaware of any prior studies investigating the association between DNA methylation of the MAOB gene and major depression in human populations.

Although it is well recognized that early life adversity is a strong predictor of adverse health outcomes later in life,44 exposure to different forms of childhood trauma may result in different clinical symptoms/outcomes, although the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be determined. For instance, in a previous study including 533 children (mean age 10 years), those exposed to physical or sexual abuse in their early years of life exhibited different patterns of cortisol fluctuations during a day, indicating differential neuroendocrine responses to different types of early traumatic experiences.45 In another study, women who were sexually abused or emotionally mistreated before the onset of puberty displayed differential changes in the architecture of their brains, probably reflecting the specific neuroendocrine responses to different traumatic exposures during their early life.46 Consistent with previous studies, here we observed differential DNA methylation patterns of stress-related genes in response to different domains of childhood traumatic experiences. Specifically, we found that hypermethylation of one CpG probe in the MAOB gene appeared to be responsive to sexual abuse (P=0.04) but not to other forms of traumatic experiences. Moreover, hypermethylation of several CpG sites in the NR3C1 gene appeared to be associated with physical abuse but not other types of traumatic experiences. Our results corroborate these previous findings and suggest that exposure to different types of traumatic experiences may leave specific epigenetic marks on stress-related genes. Thus, altered DNA methylation may underlie, at least in part, the differential impact of different types of early trauma on depression later in life.

Despite the accumulating evidence suggesting that DNA methylation of stress responsive genes may mediate the effect of childhood trauma on depression,3, 14, 22 no study has statistically tested this in a systematic manner. Here, we demonstrated that over 20% of the association between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms was mediated through 2 CpG sites in the NR3C1 and BDNF genes. The mediating CpG site in the NR3C1 gene identified in the current study (locates in the promoter 1F region) has previously been associated with childhood maltreatment,47 early parental loss,43 and depression.16 In addition, we found that hypermethylation of a CpG probe in the BDNF gene was positively associated with depressive symptoms, which appears to be consistent with previous research demonstrating that a decreased serum BDNF level was associated with depression,19, 48 and decreased synthesis of BDNF level in the neurons was correlated with hypermethylation of the BDNF gene.49

Our study has several limitations. First, due to using two different platforms for DNA methylation analysis in our discovery and replication samples, the majority of the CpG sites assayed in the two studies were not completely overlapped. While this did not allow us to replicate the association of an individual CpG methylation with depressive symptoms across the two studies, our goal here is to test the joint rather than individual effect of DNA methylation at multiple CpG sites, and the lack of overlapping for single CpGs across the two studies did not affect our gene- and pathway-based association analyses. Second, we assayed DNA methylation in peripheral blood, but as DNA methylation is tissue-specific, it is unclear whether or to what extent our results could reflect DNA methylation changes in the brain, the target organ of depression. According to the algorithm suggested by Mill and colleagues, we found significant correlations in DNA methylation of the MAOA and MAOB genes between white blood cells and the brain tissue, whereas no significant correlation was detected for the other three genes, e.g., BDNF, NR3C1, and SLC6A4.50 However, accumulating evidence indicated that epimutations may not be limited to the affected tissue but could also be detected in peripheral blood.51 Third, although we used monozygotic twin pairs design, our gene-based and gene-set analyses were based on mixed linear model rather than co-twin control analysis in consideration of the small sample size which would be halved again in matched pair analysis. Thus, although our analysis adjusted for many known clinical factors, we cannot exclude the possibility of potential confounding by shared familial factors (e.g., shared genes, shared early life environment, e.g., in utero environment, maternal nutrition, etc.), and our results should not be over interpreted. Fourth, as all twins included in the current analysis are young to middle-aged European white participants, the generalizability of our results to other age or ethnic groups is uncertain. Fifth, as all observational studies, we cannot determine the causal effect of DNA methylation on depressive symptoms. Moreover, as all studies using MZ twins, the sample size of our study is relatively small that no CpG sites represented statistically significant associations with both childhood trauma and depressive symptoms. However, mediation analysis based on the nominally significant CpG sites demonstrated significant mediations of CpG methylation between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in our study. Even though we were able to replicate the results across two studies, our results may still need to be confirmed or refused in larger populations with different clinical settings. Lastly, data on white blood cell type proportions was not available in the THS, we cannot eliminate the influence of cell type on our results.

Nonetheless, our study has several strengths. First, we used innovative statistical methods to test the joint association of DNA methylation at multiple CpG sites in one or more stress-related genes with depressive symptoms. Our results provide initial evidence that altered DNA methylation of the stress system jointly contributes to depression, and highlight the importance of testing the combined rather than the individual effect of epigenetic markers on human complex traits. Second, although previous studies have reported the relationship between childhood trauma, DNA methylation of stress-related genes, and major depression,15–21 the mediating effect of DNA methylation in multiple stress-related genes on the association of childhood trauma with depressive symptoms has not been systematically examined as the one presented here. Our mediation analysis demonstrated that DNA methylation of two stress-related genes (BDNF, NR3C1) mediate, either individually or jointly, the association between childhood trauma and depression. This finding may unravel a molecular pathway through which early life traumatic experiences become biologically embedded in the risk of depression. Third, although we were unable to replicate the results of single CpG association analysis across the two studies due to using different platforms for DNA methylation assays, we were able to successfully replicate the joint association of DNA methylation of five stress-related genes with depressive symptoms in two MZ twin studies at both the gene- and pathway-levels.

In summary, we demonstrate that altered DNA methylation in stress-related genes are jointly associated with depressive symptoms, and partially mediates the association of childhood trauma with depression later in life. Our results may unravel a molecular mechanism through which early life stress becomes biologically embedded in the risk of depression during adulthood, and highlight the importance of testing the combined effects of multiple CpG methylation on human complex traits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has provided financial support for the development and maintenance of the Vietnam Era Twin Registry (VETR). Numerous organizations have provided invaluable assistance in the conduct of this study, including Department of Defense; National Personnel Records Center, National Archives and Records Administration; the Internal Revenue Service; National Institutes of Health; National Opinion Research Center; National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences; the Institute for Survey Research, Temple University. Most importantly, the authors gratefully acknowledge the continued cooperation and participation of the members of the VET Registry and their families. Without their contribution, this research would not have been possible.

Source of Funding: This study was supported by NIH grants R01MH097018, R01DK091369, R21HL092363, and K01AG034259. These funding have no role in design, analysis, interpretation, or paper writing of this manuscript.

Glossary

- MZ

monozygotic

- THS

Twins Heart Study

- VETR

Vietnam Era Twin Registry

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- MMS

Mood and Methylation Study

- UWTR

University of Washington Twin Registry

- EWAS

epigenome-wide association study

- ETISR-SF

Early Trauma Inventory Self Report - Short Form

- BMI

body mass index

- AUDIT

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- wTPM

weighted truncated product method

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions: HP and JZ drafted the manuscript. HP and YZ conducted statistical analyses. JZ conceptualized the study, contributed to data acquisition and data interpretation. ES, EF, TB, PRB, and JG revised the manuscript and provided critical comments on data interpretation. All authors approved the final version.

References

- 1.Organization., W.H. Depression: A Global Crisis. World Mental Health Day, October 10 2012. Occoquan: World Federation for Mental Health. 2012 available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/wfmh_paper_depression_wmhd_2012.pdf.

- 2.Li M, D’Arcy C, Meng X. Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychol Med. 2016;46(4):717–30. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Effects of the Social Environment and Stress on Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Methylation: A Systematic Review. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne EM, Carrillo-Roa T, Henders AK, Bowdler L, McRae AF, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Krause L, Wray NR. Monozygotic twins affected with major depressive disorder have greater variance in methylation than their unaffected co-twin. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e269. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordova-Palomera A, Fatjo-Vilas M, Gasto C, Navarro V, Krebs MO, Fananas L. Genome-wide methylation study on depression: differential methylation and variable methylation in monozygotic twins. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e557. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malki K, Koritskaya E, Harris F, Bryson K, Herbster M, Tosto MG. Epigenetic differences in monozygotic twins discordant for major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(6):e839. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Numata S, Ishii K, Tajima A, Iga J, Kinoshita M, Watanabe S, Umehara H, Fuchikami M, Okada S, Boku S, Hishimoto A, Shimodera S, Imoto I, Morinobu S, Ohmori T. Blood diagnostic biomarkers for major depressive disorder using multiplex DNA methylation profiles: discovery and validation. Epigenetics. 2015;10(2):135–41. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2014.1003743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato T, Iwamoto K. Comprehensive DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation analysis in the human brain and its implication in mental disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2014;80:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker RM, Christoforou AN, McCartney DL, Morris SW, Kennedy NA, Morten P, Anderson SM, Torrance HS, Macdonald A, Sussmann JE, Whalley HC, Blackwood DH, McIntosh AM, Porteous DJ, Evans KL. DNA methylation in a Scottish family multiply affected by bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:5. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladd-Acosta C, Hansen KD, Briem E, Fallin MD, Kaufmann WE, Feinberg AP. Common DNA methylation alterations in multiple brain regions in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):862–71. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta D, Klengel T, Conneely KN, Smith AK, Altmann A, Pace TW, Rex-Haffner M, Loeschner A, Gonik M, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Muller-Myhsok B, Ressler KJ, Binder EB. Childhood maltreatment is associated with distinct genomic and epigenetic profiles in posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(20):8302–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217750110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cittaro D, Lampis V, Luchetti A, Coccurello R, Guffanti A, Felsani A, Moles A, Stupka E, FR DA, Battaglia M. Histone Modifications in a Mouse Model of Early Adversities and Panic Disorder: Role for Asic1 and Neurodevelopmental Genes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25131. doi: 10.1038/srep25131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smart C, Strathdee G, Watson S, Murgatroyd C, McAllister-Williams RH. Early life trauma, depression and the glucocorticoid receptor gene–an epigenetic perspective. Psychol Med. 2015;45(16):3393–410. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vangeel E, Van Den Eede F, Hompes T, Izzi B, Del Favero J, Moorkens G, Lambrechts D, Freson K, Claes S. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and DNA Hypomethylation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Promoter 1F Region: Associations With HPA Axis Hypofunction and Childhood Trauma. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(8):853–62. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dempster EL, Wong CC, Lester KJ, Burrage J, Gregory AM, Mill J, Eley TC. Genome-wide methylomic analysis of monozygotic twins discordant for adolescent depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(12):977–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyrka AR, Parade SH, Welch ES, Ridout KK, Price LH, Marsit C, Philip NS, Carpenter LL. Methylation of the leukocyte glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter in adults: associations with early adversity and depressive, anxiety and substance-use disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(7):e848. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Januar V, Ancelin ML, Ritchie K, Saffery R, Ryan J. BDNF promoter methylation and genetic variation in late-life depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e619. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chagnon YC, Potvin O, Hudon C, Preville M. DNA methylation and single nucleotide variants in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and oxytocin receptor (OXTR) genes are associated with anxiety/depression in older women. Front Genet. 2015;6:230. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuster R, Kleimann A, Rehme MK, Taschner L, Glahn A, Groh A, Frieling H, Lichtinghagen R, Hillemacher T, Bleich S, Heberlein A. Elevated methylation and decreased serum concentrations of BDNF in patients in levomethadone compared to diamorphine maintenance treatment. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0668-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J, Goldberg J, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V. Association between promoter methylation of serotonin transporter gene and depressive symptoms: a monozygotic twin study. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(6):523–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182924cf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei MK, Beach SR, Simons RL, Philibert RA. Neighborhood crime and depressive symptoms among African American women: Genetic moderation and epigenetic mediation of effects. Social science & medicine. 2015;146:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Knaap LJ, Oldehinkel AJ, Verhulst FC, van Oort FV, Riese H. Glucocorticoid receptor gene methylation and HPA-axis regulation in adolescents. The TRAILS study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;58:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah S, Bonder MJ, Marioni RE, Zhu Z, McRae AF, Zhernakova A, Harris SE, Liewald D, Henders AK, Mendelson MM, Liu C, Joehanes R, Liang L, Consortium B. Levy D, Martin NG, Starr JM, Wijmenga C, Wray NR, Yang J, Montgomery GW, Franke L, Deary IJ, Visscher PM. Improving Phenotypic Prediction by Combining Genetic and Epigenetic Associations. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(1):75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breton CV, Marsit CJ, Faustman E, Nadeau K, Goodrich JM, Dolinoy DC, Herbstman J, Holland N, LaSalle JM, Schmidt R, Yousefi P, Perera F, Joubert BR, Wiemels J, Taylor M, Yang IV, Chen R, Hew KM, Freeland DM, Miller R, Murphy SK. Small-Magnitude Effect Sizes in Epigenetic End Points are Important in Children’s Environmental Health Studies: The Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center’s Epigenetics Working Group. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(4):511–526. doi: 10.1289/EHP595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J, Goldberg J, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V. Global DNA methylation is associated with insulin resistance: a monozygotic twin study. Diabetes. 2012;61(2):542–6. doi: 10.2337/db11-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afari N, Noonan C, Goldberg J, Edwards K, Gadepalli K, Osterman B, Evanoff C, Buchwald D. University of Washington Twin Registry: construction and characteristics of a community-based twin registry. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9(6):1023–9. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. Vol. 1. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(3):211–8. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243824.84651.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1363–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D, Beck S. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(2):189–96. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS. Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure-time physical activity. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(4):685–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao J, Forsberg CW, Goldberg J, Smith NL, Vaccarino V. MAOA promoter methylation and susceptibility to carotid atherosclerosis: role of familial factors in a monozygotic twin sample. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaykin DV, Zhivotovsky LA, Westfall PH, Weir BS. Truncated product method for combining P-values. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;22(2):170–85. doi: 10.1002/gepi.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheng X, Yang J. Truncated Product Methods for Panel Unit Root Tests. Oxf Bull Econ Stat. 2013;75(4):624–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.2012.00705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Zhu Y, Cole SA, Haack K, Zhang Y, Beebe LA, Howard BV, Best LG, Devereux RB, Henderson JA, Henderson P, Lee ET, Zhao J. A gene-family analysis of 61 genetic variants in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in American Indians. Diabetes. 2012;61(7):1888–94. doi: 10.2337/db11-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Zhu Y, Lee ET, Zhang Y, Cole SA, Haack K, Best LG, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Howard BV, Zhao J. Joint associations of 61 genetic variants in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes with subclinical atherosclerosis in American Indians: a gene-family analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6(1):89–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.963967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y, Yang J, Li S, Cole SA, Haack K, Umans JG, Franceschini N, Howard BV, Lee ET, Zhao J. Genetic variants in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes jointly contribute to kidney function in American Indians: the Strong Heart Family Study. J Hypertens. 2014;32(5):1042–8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000151. discussion 1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu Y, Yang J, Yeh F, Cole SA, Haack K, Lee ET, Howard BV, Zhao J. Joint association of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor variants with abdominal obesity in American Indians: the Strong Heart Family Study. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preacher KJ, Selig JP. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures. 2012;6(2):77–98. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuchikami M, Morinobu S, Segawa M, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S, Ozaki N, Inoue T, Kusumi I, Koyama T, Tsuchiyama K, Terao T. DNA methylation profiles of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene as a potent diagnostic biomarker in major depression. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Labonte B, Yerko V, Gross J, Mechawar N, Meaney MJ, Szyf M, Turecki G. Differential glucocorticoid receptor exon 1(B), 1(C), and 1(H) expression and methylation in suicide completers with a history of childhood abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(1):41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melas PA, Wei Y, Wong CC, Sjoholm LK, Aberg E, Mill J, Schalling M, Forsell Y, Lavebratt C. Genetic and epigenetic associations of MAOA and NR3C1 with depression and childhood adversities. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(7):1513–28. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heim C, Binder EB. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp Neurol. 2012;233(1):102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Gunnar MR, Toth SL. The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school-aged children. Child Dev. 2010;81(1):252–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heim CM, Mayberg HS, Mletzko T, Nemeroff CB, Pruessner JC. Decreased cortical representation of genital somatosensory field after childhood sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):616–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weder N, Zhang H, Jensen K, Yang BZ, Simen A, Jackowski A, Lipschitz D, Douglas-Palumberi H, Ge M, Perepletchikova F, O’Loughlin K, Hudziak JJ, Gelernter J, Kaufman J. Child abuse, depression, and methylation in genes involved with stress, neural plasticity, and brain circuitry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):417–24 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sen S, Duman R, Sanacora G. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: meta-analyses and implications. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(6):527–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinowich K, Hattori D, Wu H, Fouse S, He F, Hu Y, Fan G, Sun YE. DNA methylation-related chromatin remodeling in activity-dependent BDNF gene regulation. Science. 2003;302(5646):890–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hannon E, Lunnon K, Schalkwyk L, Mill J. Interindividual methylomic variation across blood, cortex, and cerebellum: implications for epigenetic studies of neurological and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Epigenetics. 2015;10(11):1024–32. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1100786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menke A, Binder EB. Epigenetic alterations in depression and antidepressant treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(3):395–404. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.3/amenke. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.