Abstract

While prior research has demonstrated the benefits of self-affirming individuals prior to exposing them to potentially threatening health messages, the current study assesses the feasibility of inducing self-affirmation vicariously through the success of a character in a narrative. College-age participants who regularly use e-cigarettes (N = 379) were randomly assigned to one of four conditions (vicarious affirmation, vicarious control, traditional affirmation, traditional control). The vicarious conditions read one of two versions of a story depicting a college student of their own gender. The versions were identical except in the vicarious self-affirmation condition (VSA), the main character achieves success (i.e., honored with a prestigious award) before being confronted by a friend about the dangers associated with their e-cigarette use; whereas in the vicarious control condition, the achievement is mentioned after the risk information. Results of the posttest and 10-day follow-up demonstrated that VSA mimicked the underlying mechanisms of traditional self-affirmation, reducing messages derogation, and increasing self-appraisal and perceived risk. The effect of VSA on e-cigarette outcomes was moderated by frequency of use, with heavier users benefiting the most. Theoretical and practical implications for tobacco regulatory science are discussed.

Keywords: Self-affirmation, narrative persuasion, e-cigarettes, risk, vicarious experience

When electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) were introduced into the United States in 2006, they were celebrated as a healthier alternative to traditional cigarettes and a potential first step toward smoking cessation (Hajek et a., 2014). A decade later, however, e-cigarettes are gradually becoming one of the most common entry points for nicotine addiction (Abrams, 2014; Trumbo & Harper, 2013). In fact, recent data shows that e-cig users are 2.5 times more likely to start smoking regular cigarettes than non-users (Littlefield et al., 2015; Sutfin et al., 2015).

Younger users have proven to be particularly susceptible to e-cigarettes. According to the 2016 Report of the Surgeon General, e-cigarette use among high school students has grown “an astounding 900%” from 2011 to 2015 (p. vii) with 16% using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. Indeed, in 2014 e-cigarettes became the commonly used form of tobacco among youth 18–24 in the United States and, as the Surgeon General’s report points out, while e-cigarettes may include fewer toxicants than combustible tobacco products, they are far from being harmless and can damage the developing adolescent brain and cause addiction.

Though regulatory legislation such as incorporating e-cigarettes into existing smoke free policies and consumer education will be critical to reversing this trend, the availability of information alone is not sufficient to change behavior. Users are notoriously resistant to anti-tobacco information, tending to deny its relevance and downplay their risk (Peretti-Watel et al., 2007). Moreover, younger users have been among the most difficult to convince of tobacco-related risks (Moran & Sussman, 2015). The current study builds upon prior work in self-affirmation theory, shifting the focus from communication strategies that emphasize guilt, risk, and fear to messages that enhance susceptibility to change by casting the self in a positive light.

Self-affirmation

According to self-affirmation theory, people are motivated to maintain a positive perception of the self (Steele, 1988). When faced with information that threatens that positive perception, individuals tend to counter the threat by focusing instead on a different positive aspect of the self (Cohen et al., 2007; Sherman et al., 2013). For instance, failing an exam may threaten a college student’s belief they are highly intelligent. In response, they may focus on the fact that they are friendly and popular in order to maintain their overall positive conception of themselves. In the health context, this tendency may result in people rejecting or minimizing the relevance of important information about potentially threatening health risks. In fact, a number of studies have established this function as an effective defense mechanism when individuals are exposed to information that contradicts their beliefs, attitudes, and behavior (Toma & Hancock, 2013). Interestingly, by encouraging individuals to reflect on an important domain of the self before exposing them to a threatening message, self-worth can be preemptively bolstered in such a way as to bypass the defensive mechanisms that would otherwise inhibit persuasion (Steele, 1988; Steele & Liu, 1983). This point has been further explored by Critcher, Dunning, and Armor (2010), demonstrating that an a priori self-affirmation intervention tends to be effective in reducing defensiveness, whereas affirmations introduced after the threat are only effective if participants have yet to reach a defensive conclusion.

Studies employing a priori self-affirmation have consistently shown that self-affirmation before exposure to a threat can foster greater receptivity to otherwise self-threatening information (Kim & Niederdeppe, 2016; Klein et al., 2015). For instance, Düring and Jessop (2014) investigated the impact of a self-affirming intervention on promoting openness to a message highlighting the risks of insufficient exercise. The authors found that self-affirmed individuals reported on more positive attitudes and intentions toward increasing their exercise routine, together with lower message derogation, compared to nonaffirmed participants. Other studies explored whether a self-affirming manipulation could increase fruit and vegetable intake (Epton & Harris, 2008). As predicted, self-affirmed participants reported eating significantly more portions of fruit and vegetables (an increase of approximately 5.5 portions across the week), in comparison to the control condition. This unique capacity of self-affirmation to bypass resistance occurs because, presumably, an a priori focus on strong and valued aspects of the self can offset the impact of threats in other domains, such that ego-defensive strategies (e.g., denial, rationalization, avoidance) are no longer needed (Davis et al, 2016). Overall, in both lab and field experiments, the effects of self-affirmation have been shown to hold across a range of health behaviors, including smoking, alcohol intake, caffeine intake, sunscreen use, and type 2 diabetes; among different segments of the population; and with short-term as well as long-term effects (for meta-analyses see Epton et al., 2015; Sweeney & Moyer, 2015). That being said, it is important to acknowledge the fact that while there is a growing body of evidence that points to the efficacy of self-affirming interventions, there remains a considerable lack of clarity regarding the underlying mechanisms that produce the self-affirmation effect. Namely, while Steele (1988) saw self-affirmation effects arising from discrepancies between positive self-perception (induced by value affirmation) and incongruent behavior, Tesser (2000) argued that self-affirmation is a self-esteem maintenance mechanism that regulates potential threats. More recently, Falk et al. (2015) utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to identify potential neural mechanisms of affirmation. Focusing on the brain’s ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), the results showed that self-affirmed participants exhibit a more positive evaluation of stimuli as reflected in increased brain activity.

Another characteristic of self-affirmation that makes it a highly likely candidate for tobacco-related interventions is the fact that both self-affirmation and tobacco use have a recursive nature. Namely, attempting to stop using tobacco may often involve a recursive cycle, in which initial failure discourages further attempts, prompting a continuing process of demotivation (Redish, Jensen, & Johnson, 2008). Given that early outcomes set the starting point in the initial trajectory of a recursive cycle and can therefore have disproportional influence (Cohen et al., 2009), a well-timed self-affirming intervention could provide a better starting point for individuals who want to stop using tobacco. For instance, longitudinal field experiments in schools have repeatedly shown that value affirmation (manipulated by writing exercises) can attenuate achievement gaps between minority students and European American students, with effects persisting for several years (Cohen et al., 2009; Sherman et al., 2013). These recursive effects are often attributed to the ability of self-affirmation to broaden personal construals and prevent daily adversities from being recognized as identity threats (Sherman et al., 2013).

While the vast majority of studies within the self-affirmation tradition artificially induce participants with self-affirming cognitions, a more recent line of research has explored whether people spontaneously self-affirm when under threat. Defined as the “extent to which people think about their values or strengths when they feel threatened” (Persoskie et al., 2015, p. 46), spontaneous self-affirmation is treated as an individual-level characteristic that predicts various health-related benefits. For instance, Taber et al. (2016) found that spontaneous self-affirmation (measured with the items “when I feel threatened or anxious I find myself thinking about my strengths” and “when I feel threatened or anxious I find myself thinking about my values) is associated with lower likelihood of cognitive impairments and greater positive affect among cancer survivors. Similarly, others have found spontaneous self-affirmation to be a significant correlate of well-being (Emanuel et al., 2016), health-related information seeking (Taber et al., 2015), and willingness to receive self-threatening genetic risk information (Ferrer et al., 2015). Though spontaneous self-affirmation is a promising prospect for further research (Harris & Epton 2010), its current implementation has not been without criticism. For example, Sparks and Jessop (2016) refer to the measurement of spontaneous self-affirmation as a bit of a misnomer in the sense that it alludes to self-affirmation as an unplanned response, substantially deviating from the common understanding of self-affirmation. Further, the literature on spontaneous self-affirmation suffers from a more general limitation of relying on cross-sectional data, which limits the ability to promote causal claims or estimate whether spontaneous and traditional self-affirmation differ in important respects. With that in mind, it is important to note that some studies do go beyond correlational data to identify everyday life self-affirmation. For instance, in a series of two studies Toma and Hancock (2013) provided compelling evidence for self-affirmation as a mechanism underlying Facebook use, observing that participants tended to gravitate toward their online profiles after experiencing a threat to the ego (i.e., negative feedback) as a self-affirming strategy. Another notable example is a long period field experiment that attempted to demonstrate that people can be trained to spontaneously self-affirm (Brady et al., 2016). In this case, the authors initiated a traditional self-affirmation intervention (i.e., reflecting on core personal values) among Latino and White students during their first or second year of college. As expected, this intervention improved Latino students’ GPA over a period of two years. More importantly, after the same students were recruited for a follow-up session involving an academic stressor salience task about their end-of-semester requirements, Latino students generated more self-affirming and less self-threatening cognitions, as gauged with an open-ended question. These results point to the need to reconsider the practical applications of self-affirmation.

To date, the application of self-affirming interventions in everyday situations has been limited due to two primary factors. First, self-affirming interventions typically require participants to complete an exercise, such as writing a brief essay about a value of importance (Crocker, Niiya, & Mischkowski, 2008; McQueen & Klein, 2006) or responding to a Values in Action questionnaire (Kim & Niederdeppe, 2016; Napper, Harris, & Epton, 2009). Although the efficacy of these activities to foster self-affirmation has been validated numerous times, the degree of individual effort and intrusiveness involved makes such approaches impractical for large-scale interventions (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). It is therefore not surprising that nearly all field studies of self-affirmation have been conducted in an educational context, where essays can seamlessly be integrated into everyday activity (for a review see Cohen & Sherman, 2014). Second, the theory fails to account for selective exposure whereby individuals often actively avoid threatening messages (Case et al., 2005). Thus, even if users are encouraged to be more receptive to threatening information, the question remains of whether individuals will willingly seek out this information when not under the constraints of a laboratory experiment. In short, it is unclear whether self-affirmation can overpower mechanisms of selective exposure, such as reinforcement seeking (Garrett, 2009; Knobloch-Westerwick, & Lavis, 2017).

In order to utilize self-affirmation and reduce resistance to threatening health messages, both of these issues – the need for naturalistic methods to promote self-affirmation and selective exposure – must be addressed. Below we put forth one potential vehicle – narratives.

Narrative persuasion

Interest in fictional narratives that integrate health-related information has grown exponentially in recent years (Braddock & Dillard, 2016). Conventional nonnarrative modes of delivering information, such as informational brochures or public service announcements, include didactic styles of communication that appeal to reason (Kreuter et al., 2010). As such, traditional nonnarrative health messages depend heavily on an audience’s motivation to rationally process information, and may be subject to resistance as individuals seek to distance themselves from threats. In contrast, narratives that embed the risk information within a coherent story leverage cognitive and emotional involvement to engage the audience and reduce resistance. As Moyer-Gusé (2008) explains, “when viewers are engaged in the dramatic elements of an entertainment program, they are in a state of less critical, more immersive engagement” (p. 413), which allows them to be more open to otherwise threatening information.

The efficacy of stories in changing health-related attitudes and behavior has been well-documented. For instance, Morgan, Movius, and Cody (2009) found that exposure to a narrative portraying the merits of organ donation significantly increased viewers’ likelihood of becoming donors themselves. Perhaps the strongest evidence of the relative efficacy of narratives over nonnarratives comes from a large-scale randomized control trial of 900 women who were assigned to receive the same cervical cancer related information in either a narrative or nonnarrative format. Although both formats increased knowledge, women in the narrative condition were significantly more likely to be screened at six months (Murphy et al., 2015).

One of the central postulates of narrative persuasion is that involvement with fictional characters can mimic interpersonal influence (Cohen, 2001; Green, 2006). Echoing the main tenets of Social Cognitive Theory, this suggests that behavior modeled by mediated others is a powerful source of information and persuasion (Bandura, 1986). By observing modeled behavior, “people may vicariously experience the full spectrum of challenges and expectations of a certain behavior and, in the process, acquire the knowledge and skills needed to successfully perform the behavior” (Lu et al., 2012, p. 201). This effect appears to be particularly pronounced when narratives involve characters perceived as similar to the audience or with whom the audience identifies (Bandura, 2002; Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007). This is not to suggest that vicarious experience should be equated with direct experience; yet, the literature provides some compelling evidence that individuals can change their attitudes and behavior when witnessing members of important groups. For instance, Bandura (1977) identified vicarious experience (i.e., watching others model a behavior) as an important source for self-efficacy beliefs, along with performance accomplishments, verbal persuasion, and physiological states. More recently, studies have demonstrated that cognitive dissonance can be induced vicariously, mimicking processes associated with the traditional cognitive dissonance paradigm (Monin et al., 2004; Norton et al., 2003). These findings are attributed to the highly developed ability of individuals at estimating other people’s thoughts and emotions by imagining how they would act and feel in similar situations. If high involvement in a story allows the audience to experience the mental and emotional state of a character, it opens the possibility of stimulating self-affirmation vicariously through the character. If so, narratives could expand the reach and impact of self-affirmation well beyond its previous applications.

Vicarious self-affirmation (VSA)

Broadly speaking, traditional research designs of self-affirmation effects on health-related outcomes consist of two distinct components: a self-focused task (such as writing about a value important to you) and a persuasive message. As previously stated, the order in which these elements are presented can determine whether individuals will be more receptive to the threatening information (Critcher, Dunning, & Armor, 2010; Steele, 1988). Whereas affirming after a threat (i.e., persuasive message → self-focused task) often encourages biased processing, an a priori self-affirmation (self-focused task → persuasive message) preemptively reduces the threat and induces higher levels of receptivity. Translating this procedure to a vicarious experience would require an additional component, where individuals identify with a mediated character who self-affirms. In other words, VSA is contingent on the capacity of the narrative to induce identification between the audience and relevant characters. Under these conditions, cognitive and emotional involvement with a self-affirming character may prompt corresponding self-affirmation for the audience member as well.

One of the key indicators of self-affirmation is the extent to which self-affirmed individuals derogate the threatening message. By discounting, deprecating, and minimizing the relevance of health information, individuals can restore and maintain their self-integrity. Compared to their nonaffirmed counterparts, self-affirmed individuals are less likely to derogate threatening health-related information and more likely to accept the information as accurate and relevant (van Koningsbruggen & Das, 2009). In addition, Napper, Harris, and Epton (2008) developed and validated a scale of self-appraisal as a proxy for self-affirmation, demonstrating that, compared to nonaffirmed participants, self-affirmed individuals have a more positive self-appraisal. Therefore, the first step in assessing the feasibility of VSA should test the ability of a narrative with a self-affirmed character to influence message derogation and self-appraisal, compared to a more traditional and established self-affirmation exercise (i.e., essay-writing). Based on this logic, the following hypotheses were posed:

H1:

Self-affirmation (vicarious affirmation and traditional affirmation) will have a significant effect on a) message derogation; and b) self-appraisal, such that affirmed participants will tend to report lower levels of message derogation and higher self-appraisal, compared to participants in the control conditions (vicarious control and traditional control).

H2:

Self-affirmation (vicarious affirmation and traditional affirmation) will have a significant effect on e-cigarette-related outcomes, including a) e-cigarette risk perceptions; and b) intentions to stop using e-cigarettes, such that affirmed participants will tend to report on higher risk perceptions and an increase in intention to stop using e-cigarettes, compared to participants in the control conditions (vicarious control and traditional control).

H3:

The effect of VSA on e-cigarette risk perceptions and intentions to stop using e-cigarettes, will be mediated by a) message derogation; and b) self-appraisal.

In addition, keeping in mind that risk associated with health messages is proportional to the perceived relevance of the health threat, stronger effects are usually observed for those at greatest risk (Harris & Napper, 2005). Simply put, if a college student only rarely uses e-cigarettes, there is little reason to expect that health-related information regarding this practice would significantly threaten their self-integrity. Namely, e-cigarettes are likely to be peripheral to their self-perception and would, presumably, provoke little motivation to engage in defensive processing. Conversely, someone who uses e-cigarettes on a daily basis should have a greater resistance to information challenging this behavior. This assumption is supported by previous studies that treat issue-involvement as a moderator. For instance, Reed and Aspinwall (1998) demonstrated that self-affirmation results in less biased processing of information regarding the link between caffeine consumption and fibrocystic disease, but only among higher frequency caffeine consumers. Likewise, Harris and Napper (2005) provide evidence that higher risk self-affirmed participants show greater acceptance of the personal relevance of breast cancer than those with lower risk. More recently, the ability of self-affirmation to increase sensitivity to self-relevant information was corroborated in a study that analyzed responses to graphic antismoking images, concluding that self-affirmation was effective only among regular smokers (Kessels et al., 2016). Based on this, the final hypothesis is posed:

H4:

The effect of VSA on e-cigarette-related outcomes will be moderated by frequency of e-cigarette use, such that stronger effects will be recorded for heavier users.

Study context: E-cigarette use among youth

E-cigarettes are the latest in a long line of “reduced harm” products that deliver nicotine while removing some of the harmful elements in cigarette smoke (see Surgeon General’s 2016 Report for a review). But in addition to nicotine (which is highly addictive and particularly detrimental to developing adolescent brains), e-cigarette areosol has been shown to contain other harmful ingredients, making it far from harmless. Because e-cigarettes were only introduced a decade ago, the longer-term health effects of their use - commonly referred to as vaping - have yet to be verified. However, mounting evidence has led the Surgeon General to recently declare that “E-cigarette use among U.S. youth and young adults is now a major public health concern” (2016, p.vii). These populations have long been a core target for the conventional tobacco industry, and are now proving a dominant and growing market for e-cigarettes. As previously noted, the prevalence of e-cigarette use among youth is estimated to have tripled between 2011 and 2013, and tripled again between 2013 and 2014 to an estimated 2.4 million middle and high school users (Centers for Disease Control, 2015).

In recent years, there has been an increased push for regulation and consumer education regarding e-cigarettes. As of August 2016, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has extended the reach of key provisions in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act to cover e-cigarettes, which is expected to significantly reduce access to e-cigarettes among minors. Even with greater oversight and education, however, information will be necessary but not sufficient to change behavior, particularly among legal college-age populations. Efforts targeting young adults will also have to account for the major role of peer pressure and selective exposure in contributing to tobacco use (Ahern & Mechling, 2014; Taylor, 2015). As such, the issue of e-cigarette use among young adults offers a particularly appropriate testing ground for the effectiveness and applicability of VSA.

METHOD

Participants

Recruitment was conducted through a paid survey panel of American college age e-cigarette users maintained by Qualtrics Pools. After screening for age (18 – 28), English fluency, and e-cigarette use, 508 participants were successfully recruited to the study (354 participants in the vicarious conditions and 154 participants in the traditional conditions1). Participants in the vicarious conditions were then notified that they would be contacted ten days after the initial questionnaire to respond on a follow-up survey. Follow-up measurement assessed only the vicarious condition; the traditional condition was intended simply to provide estimates regarding the comparability of vicarious affirmation with traditional affirmation, and as such was used only for posttest measurements. Of the 354 consenting participants in the vicarious conditions who responded to the first questionnaire, 231 were successfully recontacted for the follow-up survey. Six participants were removed from the final sample due to unrealistic response time or missing data, leaving a final sample of 225 at follow-up. To ensure that attrition was unrelated to the experimental conditions, a series of ANCOVAs were conducted, yielding no significant interactions between attrition and experimental conditions. Participants were 48.9% female; Mage = 25.46, SD = 2.96; 73.1% White, 12% Hispanic, 6.9% Black, 3.7% Asian. Most (61.3%) had more than six months of experience with e-cigarettes and 50.5% used e-cigarettes more than twice a week. The highest achieved education was high school for 43.3%, followed by 4-year college degree (26.8%), Master’s degree (10.6%), 2-year college degree (10.3%), and professional degree (5.3%).

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions (vicarious affirmation, vicarious control, traditional affirmation, and traditional control). Then, in order to match participants in the vicarious conditions and the principal narrative character on gender, the questionnaire opened with items regarding sociodemographic information, including gender, age, and race. In the subsequent section, participants in the vicarious conditions were given a fictional story, titled “All in All, a Good Day,” and instructed to read it carefully. In the traditional conditions, self-affirmation was induced with a typical value-list exercise, in which participants were asked to choose their most important value on a list provided (i.e., kindness, honesty, generosity, independence, and success) and write a short paragraph describing the relevance of this value to their everyday life. Participants in the traditional control condition were not given a filler task, as previous research have shown that even non-reflective tasks can be used to self-affirm (Cohen, Aronson, & Steele, 2000). Then, participants in the traditional conditions were exposed to a message highlighting the risks of e-cigarette use. To make sure that the health-related information in all conditions was identical in terms of factual content and its salience, we piloted all versions of stimuli among a convenience sample of students (N = 32). After exposure to the stimuli, all participants responded on scales measuring message derogation, self-appraisal, perceived risk of e-cigarettes, as well as behavioral intent to use e-cigarettes in the next two years. Ten days after the initial questionnaire was administered, participants in the vicarious conditions (n = 225) were recontacted for the follow-up questionnaire, which included identical measurements of perceived risk and behavioral intent.

Material

Keeping in mind that the order in which the information is presented can either enhance (affirmation -> threat) or attenuate (threat -> affirmation) the influence of self-affirmation (Critcher, Dunning, & Armor, 2010), the stimulus in the vicarious condition attempted to fulfill three functions: identification with the main character, affirmation, and the presentation of risk information related to e-cigarette use. Specifically, in both vicarious conditions, the 20-paragraph story began by introducing the main character (Rachel/David) and fostering identification through descriptive details that emphasize the character’s similarity to the target population. Namely, Rachel/David is portrayed as typical college student who uses e-cigarettes, has disagreements with their roommate, and juggles academic and personal commitments. A key point in the story occurs when the protagonist receives an email informing them that they have been selected to receive a prestigious award for academic and civic achievements. This recognition performs the function of self-affirmation for the character by bolstering self-esteem and positive self-image. Mimicking the traditional value list task (McQueen & Klein, 2006), this passage highlights various important aspects of the self-image that are unrelated to the threatened domain (i.e., e-cigarette use). Later, upon meeting their best friend and sharing the news regarding their achievement, the main character decides to cancel their lunch plans in order to buy a refill for his/her e-cigarette. The friend uses this opportunity to confront the main character and recount the potential risks associated with e-cigarette use. This exchange functions as the threating message in the narrative -- analogous to the sort of information provided by traditional health brochures. This passage in the story was based on information from the FDA and the American Lung Association websites focusing on facts and misconceptions associated with e-cigarette use. Specifically, the message included information regarding potential toxic and addictive chemicals in e-cigarettes, the possibility of causing or worsening acute respiratory diseases, nicotine addiction, and the increasing likelihood of e-cigarette users to start smoking regular cigarettes, compared to non-users (American Lung Association, 2016; FDA, 2016).

The fundamental distinction between the vicarious conditions was the order in which these events were presented in the narrative. In the vicarious affirmation condition, the main character learns of the achievement first, and later faces the threatening information. In the vicarious control condition, the character’s achievement comes after she/he receives the threatening information. Other than this distinction, the narratives were identical in content and structure. In the traditional conditions, all participants were exposed to a one-paragraph summary of the risks associated with e-cigarette use, which were identical to those presented in the narrative.

Measures

Unless specified otherwise, all measures used seven-point Likert scales, where higher scores indicated increasing levels of agreement with an item.

Outcomes2.

Since the main focus of the current investigation was the feasibility of narratives to induce self-affirmation, we assessed VSA’s effect on common outcomes of traditional self-affirmation. First, message derogation was gauged with four items on a five-point Likert scale (Nan & Zhao, 2012), asking participants whether they believe that the information about e-cigarettes in the story was “exaggerated,” “distorted,” “overstated,” and “overblown” (α = .90). Second, to assess the extent to which the story focused participants’ attention on positive self-aspects, a scale of self-appraisal was adopted from Napper, Harris, and Epton (2009), using a bipolar seven-point scale. The items followed the stem, “the story made me think about…” and included “things that are important to me/ things that are not important to me” and “things that I don’t value about myself/ things I value about myself” (α = .85). Intentions to smoke e-cigarettes in the future were assessed with a single item, asking participants to estimate the likelihood that in the next two years they “will stop using e-cigarettes entirely.” The e-cigarette perceived risk scale was adapted from the National Adult Tobacco Survey (March, 2014) and consisted of three items, evaluating the extent to which e-cigarettes were perceived as “addictive,” “harmful,” and “risky.”

Moderator.

Issue-involvement was assessed with the frequency of e-cigarette use, ranging from 1 – “less than once a month” to 11 – “a few times each day.”

The questionnaire concluded with various sociodemographic variables, including experience with e-cigarettes, general health, level of education, religious affiliation, political ideology, and income, as well as an unobtrusive measurement of the time spent reading the short story in seconds (M = 189.30, SD = 108.87).

Analysis of the data began with assessments of differences across conditions utilizing ANOVAs and using planned contrasts between self-affirmation conditions (vicarious and traditional) and control conditions (vicarious and traditional) in SPSS version 21. This was followed with a mediation and moderation analyses in PROCESS, including interpretation of the moderating effects, using the Johnson-Neyman procedure (Hayes, 2013).

Results

Preliminary analysis

Before assessing the research hypotheses, ANOVAs and a series of chi-square tests examined whether there were any systematic differences between the experimental conditions. As indicated in Table 1, there were no significant difference between the experimental conditions. This result indicated that the randomization procedure was successful in creating two relatively equivalent groups.

Table 1.

Percentages, means, standard deviations (in parentheses), and chi-square/t tests for research variables

| Variable | Vicarious | Traditional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-affirmation | Control | Self-affirmation | Control | χ2/F | ||

| Age | 26.10 (2.73) | 25.74 (2.50) | 24.27(2.51) | 25.26 (3.06) | 2.32 | |

| Gender | 3.24 | |||||

| Females | 44.6% | 54.4% | 49.2% | 52.9% | ||

| Race | 29.17 | |||||

| White | 80% | 78.1% | 63% | 68.8% | ||

| Hispanic | 10.9% | 10.5% | 16.4% | 11.4% | ||

| Black | 6.4% | 5.3% | 11% | 6.3% | ||

| Asian | 1.8% | 4.4% | 3.1% | 3.8% | ||

| Education | 21.14 | |||||

| 4-year college | 33.3% | 26.3% | 30.2% | 28.6% | ||

| High school | 35.1% | 44.8% | 41.3% | 39.9% | ||

| Professional | 9% | 6.1% | 4.8% | 9.2% | ||

| General health | 3.70 (0.87) | 3.51 (0.91) | 3.34 (1.01) | 3.29 (0.94) | 2.74 | |

| Household income | 23.49 | |||||

| X ≤ 40k | 25.2% | 31.6% | 31.6% | 24.7% | ||

| 40k < X ≤ 70k | 48.3% | 43.5% | 45.5% | 38.9% | ||

| 70k < X | 26.5% | 24.9% | 22.9% | 36.4% | ||

| Political Ideology | 5.20 (1.69) | 5.00 (1.66) | 4.41 (1.83) | 4.51 (1.67) | 2.52 | |

| Experience with e-cigarettes | 14.05 | |||||

| X ≤ 6 months | 41.4% | 35.9% | 40.8% | 39.4% | ||

| 6 months < X ≤ 1 year | 15.3% | 14.9% | 12% | 15.1% | ||

| 1 year < X | 43.3% | 49.2% | 47.2% | 45.5% | ||

| E-cigarette use | 5.58 (3.37) | 5.57 (3.46) | 5.27 (3.65) | 5.76 (3.49) | 2.50 | |

Note. Political ideology was measured on a 10-point scale, ranging from 1 – “liberal” to 10 – “conservative”. General health was measured on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 - “poor” to 5 - “excellent”.

Main effects

ANCOVAs with simple planned contrasts (vicarious/traditional affirmation vs. vicarious/traditional control) were used to examine whether self-affirmation had the intended effect on research outcomes, and whether there was a significant difference between the vicarious and the direct experience. As hypothesized, participants in the affirmation conditions exhibited lower levels of message derogation, F(3,373) = 6.24, p = .001; ηp2 = .05, than their counterparts in the control conditions, and higher levels of self-appraisal, F(3,373) = 7.67, p = .001; ηp2 = .06, than those participants in the control conditions. A statistically significant difference was also observed for perceived risk F(3,373) = 7.43, p = .001; ηp2 = .06, and behavioral intent F(3,373) = 4.22, p = .006; ηp2 = .03. With that in mind, in terms of planned contrasts, we were not able to support our hypothesis regarding behavioral intent, as the traditional affirmation outperformed all other conditions, and there were no significant differences between the vicarious affirmation and the two control conditions (for a complete outline of the results and the planned contrasts see Table 2). Keeping in mind that the follow-up measurements included only the vicarious conditions, we proceed to examine the hypotheses with independent samples t-tests. As hypothesized, participants in the vicarious affirmation condition tended to report on higher levels of perceived risk of e-cigarettes at follow-up, compared to the vicarious control; t (223) = 3.18, p = .002, as well as higher intention to stop using e-cigarettes in the next two years t (223) = 2.94, p = .004. Thus, the differences in behavioral intent that were not recorded at posttest emerged at follow-up, as participants in the vicarious affirmation condition had significantly higher levels of intention to stop using e-cigarettes in the future, compared to the vicarious control condition. Further, the only unobtrusive measurement in this study also points to the effectiveness of VSA. That is, vicariously affirmed participants spent significantly more time reading the narrative compared to their counterparts in the vicarious control condition t(223) = 2.66, p = .008. On the one hand, this outcome can serve as another indicator for a successful self-affirmation intervention. For instance, using eye-movement indicators, Kessels et al. (2016) found that self-affirmed participants are more likely to pay attention and increase their fixation on threatening information. On the other hand, the fact that participants in the vicarious affirmation condition read more than their counterparts in the control condition can also serve as a potential confound, thus we decided to control for reading time in the subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Summary of comparisons between principal outcomes by experimental condition

| Vicarious | Traditional | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Self-affirmation | Control | Self-Affirmation | Control | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F(3,373)/t(223) | |

| Derogation | 2.52a | 1.12 | 2.91b | 1.08 | 2.65a | 1.11 | 3.12b | 1.08 | 6.24*** |

| Self-appraisal | 4.99ab | 1.19 | 4.69b | 1.16 | 5.02a | 1.64 | 4.30c | 1.57 | 7.67*** |

| Perceived risk1 | 4.97a | 1.49 | 4.41b | 1.53 | 4.86a | 1.50 | 4.46b | 1.56 | 7.43*** |

| Behavioral intent1 | 4.09a | 1.54 | 4.18a | 1.40 | 4.81b | 1.98 | 4.04a | 1.69 | 4.22** |

| Perceived risk2 | 5.43 | 1.46 | 4.52 | 1.69 | 3.18** | ||||

| Behavioral intent2 | 5.50 | 1.43 | 4.71 | 1.68 | 2.94** | ||||

| Time spent reading | 208.13 | 127.53 | 169.97 | 97.77 | 2.66** | ||||

Note.

p < .01

p < .001.

Posttest

Follow-up.

Means with differing scripts within outcome variables are significantly different at the p < .05 based on simple planned comparisons test. Higher scores indicate higher levels on each of the measures. Minimum score on all scales = 1 and maximum score on all scales = 7, except for derogation (1–5). Time spent reading the narrative was measured in seconds.

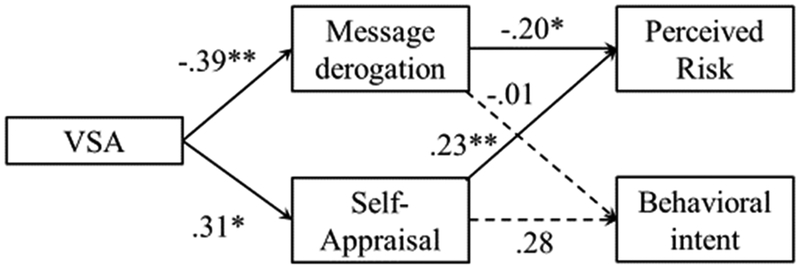

Mediation Analysis3

In order to assess the hypothesized mediation for the effect of VSA on perceived risk and behavioral intent, we used PROCESS (Model 4 set at 10,000 bootstrapped samples with CI of 95%) (Hayes, 2013), controlling for time spent reading the stimulus4. In agreement with our hypothesis, the effect of VSA on perceived risk was significantly mediated through message derogation (b = .08, SE = .06, 95% CI [.004, .231] and self-appraisal (b = .07, SE = .05, 95% CI [.004, .214]. Overall, this mediation model accounted for 15.04% of the variance in perceived risk [F (4,220) = 9.74, p < .001]. With regard to behavioral intent, the mediation analysis did not record a significant effect for derogation (b = .01, SE = .05, 95% CI [−.078, .124] or self-appraisal (b = .08, SE = .06, 95% CI [−.004, .216]. Accordingly, this model accounted for merely 11.21% of the explained variance in behavioral intent [F (4,220) = 6.94, p < .001]. Thus, we were able to find only partial support for H3 and the role played by message derogation and self-appraisal as mediators of VSA effects. Figure 1 summarizes the direct unstandardized effects of VSA, message derogation, and self-appraisal on perceived risk and behavioral intent.

Figure 1.

Unstandardized beta coefficients for the direct effects of VSA, message derogation, and self-appraisal on perceived risk and behavioral intent, controlling for reading time. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Moderation analysis

PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013; Model 1) set at 10,000 bootstrapped samples was used to examine H4. First, given that previous studies suggest that self-affirmation is particularly effective for issue-involved individuals, we used the simple moderation model in PROCESS to estimate whether the frequency of e-cigarette use plays a significant role in increasing the impact of VSA5. As predicted, the analysis indicated that issue-involvement was a significant moderator for the effect of VSA on perceived risk; b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, t(221) = 3.18, p = .002, ΔR2 =.037, and behavioral intent to stop using e-cigarettes; b = 0.10, SE = 0.05, t(221) = 1.99, p = .047, ΔR2 =.018. To probe the moderation effects, the analysis proceeded with Johnson-Neyman’s technique. In the case of perceived risk, participants who scored 4.23 or more on the issue-involvement scale (65.83% of the sample) showed a significant positive effect of VSA on risk perceptions, whereas 4.83 or more (63.43% of the sample) was the cutoff score for the significant effect of VSA on behavioral intent. Figure 1 presents the conditioned effect of VSA on perceived risk and behavioral intent.

DISCUSSION

Concerns have been growing about the public health implications of the increasing popularity of e-cigarettes. In order to reverse this trend, effective legislation that requires manufacturers to include warning labels and disclose ingredients is needed. However, as past experience indicates, laws that try to educate people typically assume that individuals involved in risky behavior are willing to listen, process the information in an unbiased manner, and eventually change their behavior. In truth, this is rarely the case. Thus, it is imperative that Tobacco Regulatory Science integrate legislation with effective communication strategies. The present study sought to inform this priority by empirically testing whether self-affirming fictional narratives can reduce resistance and increase acceptance of potentially threatening risk information.

The results show a relatively consistent pattern, whereby vicarious affirmation was able to increase participants’ susceptibility to the persuasive message, compared to the control condition. Analogous to traditional self-affirmation interventions, VSA reduced message derogation and heightened self-appraisal. Thus, simply by having the narrative first introduce positive information regarding the main character and then present the threatening message about e-cigarettes, the design prompted a positive appraisal of the self and encouraged a more balanced processing of risk information.

Considering the fact that one of the central barriers to changing tobacco-related behavior is a lack of threat-management resources (Howell, Crosier, & Shepperd, 2014), the ability of self-affirmation to highlight positive self-concepts may be particularly useful. That is, people who have a deficiency of threat-management resources could use affirming messages as a self-regulating strategy, whereby less emphasis is given to threatened domains while positive domains of the self-image become more salient.

As indicated by the mediation analysis, the effect of VSA on perceived risk regarding e-cigarettes was mediated by message derogation and self-appraisal. This suggests that reduced derogation and a more positive self-appraisal were successfully translated into an increase in the perceived risk of e-cigarettes. This finding is particularly important because it not only supports the potential of VSA to affect risk perceptions, but also provides some credence to the assumption that the underlying mechanism of VSA is similar to the way that traditional self-affirmation is expected to work. While the analysis of the follow-up data recorded a significant direct effect of VSA on behavioral intent to stop using e-cigarettes in the next two years, these effects were nonsignificant at posttest, and the mediation analysis did not indicate that message derogation or self-appraisal play any relevant role in affecting behavioral intent. Several potential explanations can account for this discrepancy. First, a potential explanation for this inconsistency can be found in our stimulus. Namely, the short narrative only emphasized potential risks and did not deal directly with the intention to stop using e-cigarettes, which may explain why the posttest recorded effects on perceived risk but not on behavioral intent. Another explanation deals with the sample of college age participants. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated an optimism bias in the context of tobacco use, as young tobacco users tend to share a belief that they can be users for a few years in their youth and then quit without significant detriment to their health (Arnett, 2000). In this case, tobacco-related behavioral intentions may be less indicative of actual future behavior, compared to adult samples. More generally, self-affirmation studies tend to retrieve very weak effects on behavioral intent that often do not translate to behavior (Epton et al., 2015; Sweeney & Moyer, 2015).

In line with previous studies of self-affirmation, stronger effects were recorded for individuals who reported on frequent use of e-cigarettes. We found that higher risk participants were more sensitive to the intervention, which resulted in increased acceptance of narrative-consistent positions. This finding highlights the relevance of issue-involvement in the process of self-affirmation. Since some topics are more central to the self-image, they are also associated with increased defensiveness (Harris & Napper, 2005). Simply put, the starting position of high-risk individuals is much more defensive compared to lower-risk individuals, increasing the relative impact of self-affirmation before exposure to the threatening message.

Overall, the findings support the concept of VSA as a feasible strategy to enhance receptivity to tobacco-related messages, especially among at-risk populations. On a theoretical level, our study integrates two highly effective perspectives on persuasion, attempting to maximize the relative advantages of each framework. Specifically, while narratives provide a new platform for self-affirming interventions, VSA offers a chance to expand the arsenal of edutainment beyond engagement with characters and behavior modeling, shifting the focus to the ways in which characters can serve as surrogates for the audience. More specifically, this symbiosis between narrative persuasion and self-affirmation may help to overcome some of the notable limitations associated with self-affirmation research, as VSA can be used to reach a larger audience and enjoy the benefits of traditional self-affirming interventions without the intrusiveness that is often accompanied with such efforts. Likewise, the fact that persuasive intent of narratives is less pronounced compared didactic messages embedded in brochures or public service announcements may help reduce initial resistance that people experience when faced with overtly persuasive formats. As well as being theoretically significant, the results also offer several practical contributions. For instance, VSA may provide a potential solution to one of the most paradoxical scenarios in awareness campaigns: namely, that the most at-risk individuals are also those most likely to actively avoid important information. By embedding self-affirming health-related messages within popular narratives, VSA may be an especially effective way of reaching younger populations who might otherwise avoid health-related information conveyed by traditional sources (Green, 2006). Further, traditional forms of persuasion often use threatening messages in an attempt to attract the attention of intended recipients, scare them into processing the information, and act in response to the message (Ferguson & Phau, 2013). Yet among tobacco users, exposure to a threatening message of this kind often arouses a high level of anxiety that can prove counterproductive (Yzer et al., 2003). A route to persuasion that entails a bolstering of the self rather than an explicit threat to self-integrity is therefore a valuable alternative.

The current study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, while the results inform us regarding college-age e-cigarette users, it remains to be seen whether and how VSA could be implemented to target other populations and health disparities. It is possible that self-affirmation may be particularly suited to younger and less informed audiences who continue to use tobacco products not because of an addiction but rather as a result of misconceptions regarding its risks. It is also important to bear in mind that the reliance on self-report data poses a substantial limitation. Additionally, it is difficult to predict whether this change will be sustainable over longer periods of time and whether intentions will translate into actual behavior. Given that the processing of information was not assessed in the current study, the extent to which participants internalized the message and how resistant they might be when confronted with counterarguments or social pressure to use e-cigarettes remains unclear.

The final concern is related to a potential boomerang effect. Namely, when conveying e-cigarette-related risks, attention should be given to the possibility of unintended consequences, such as increasing the favorability of regular cigarettes. Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study provides support for vicarious self-affirmation or VSA as a novel, soft touch message strategy that could be deployed to effectively communicate the risks of tobacco products.

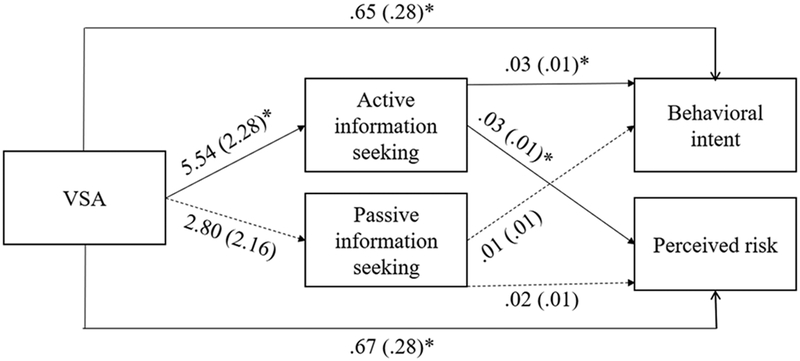

Figure 2.

Unstandardized estimates for the direct effects of VSA, active information seeking, and passive information seeking on behavioral intent and perceived risk Note. * < .05. Dashed lines illustrate nonsignificant predictors at p < .05.

Footnotes

Participants in the traditional affirmation and traditional control conditions were recruited during the manuscript’s review process thus there was a gap of six months between the procedure described for the vicarious conditions (self-affirmation and control) and the traditional conditions (self-affirmation and control).

Measures of perceived risk and behavioral intent were identical for the posttest and the follow-up questionnaires.

Given that the follow-up data did not include measurements of message derogation and self-appraisal, the mediation analysis only reports on the posttest data.

Acknowledging the confounding potential of reading time, all models treat this variable as a covariate.

The follow-up measures were used for the moderation analysis.

REFERENCES

- Abrams DB (2014). Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: Can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete? Jama, 311(2), 135–136. 10.1001/jama.2013.285347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern NR, & Mechling B (2014). E-cigarettes: A rising trend among youth. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(6), 27–31. 10.3928/02793695-20140506-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Lung Association. (2016). E-cigarettes and lung health. Retrieved from: http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/smoking-facts/e-cigarettes-and-lung-health.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Arnett JJ (2000). Optimistic bias in adolescent and adult smokers and nonsmokers. Addictive Behaviors, 25(4), 625–632. 10.1016/S0306-4603(99)00072-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura a. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive view. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bilandzic H, & Busselle R (2012). Narrative persuasion In Dillard JP, & Shen L (Eds.). The sage handbook of persuasion (Chapter 13). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Braddock K, & Dillard JP (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 7751, 1–24. 10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ST, Reeves SL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Cook JE, Taborsky-Barba S, … Cohen GL (2016). The psychology of the affirmed learner: Spontaneous self-affirmation in the face of stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(3), 353–373. 10.1037/edu0000091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Case DO, Andrews JE, Johnson JD, & Allard SL (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93(3), 353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). National youth tobacco survey (NYTS). Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/. Accessed September 20, 2016.

- Cohen GL, Aronson J, & Steele CM (2000). When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1151–1164. 10.1177/01461672002611011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, & Brzustoski P (2009). Recursive processes in self-affirmation: intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science (New York, N.Y.), 324(5925), 400–403. 10.1126/science.1170769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, & Sherman DK (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–71. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Sherman DK, Bastardi A, Hsu L, McGoey M, & Ross L (2007). Bridging the partisan divide: Self-affirmation reduces ideological closed-mindedness and inflexibility in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 415–430. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication and Society, 4(3), 245–264. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critcher CR, Dunning D, & Armor DA (2010). When self-affirmations reduce defensiveness: Timing is key. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(7), 947–959. 10.1177/0146167210369557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Niiya Y, & Mischkowski D (2008). Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive other-directed feelings. Psychological Science, 19, 740–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Soref A, Villalobos JG, & Mikulincer M (2016). Priming states of mind can affect disclosure of threatening self-information: Effects of self-affirmation, mortality salience, and attachment orientations. Law & Human Behavior, 40(40, 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Düring C, & Jessop DC (2015). The moderating impact of self-esteem on self-affirmation effects. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(2), 274–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel AS, Howell JL, Taber JM, Ferrer RA, Klein WM, & Harris PR (2016). Spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with psychological well-being: Evidence from a US national adult survey sample. Journal of Health Psychology, (May), 1359105316643595. 10.1177/1359105316643595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epton T, & Harris PR (2008). Self-affirmation promotes health behavior change. Health Psychology, 27(6), 746–752. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epton T, Harris PR, Kane R, van Koningsbruggen GM, & Sheeran P (2015). The impact of self-affirmation on health-behavior change: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 34(3), 187–196. 10.1037/hea0000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk EB, O’Donnell MB, Cascio CN, Tinney F, Kang Y, Lieberman MD, Strecher VJ (2015). Self-affirmation alters the brain’s response to health messages and subsequent behavior change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(7), 1977–82. 10.1073/pnas.1500247112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, & Lang AG (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson G, & Phau I (2013). Adolescent and young adult response to fear appeals in anti-smoking messages. Young Consumers, 14(2), 155–166. 10.1108/17473611311325555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer RA, Taber JM, Klein WMP, Harris PR, Lewis KL, & Biesecker LG (2015). The role of current affect, anticipated affect and spontaneous self-affirmation in decisions to receive self-threatening genetic risk information. Cognition and Emotion, 29(8), 1456–1465. 10.1080/02699931.2014.985188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett RK (2009). Politically motivated reinforcement seeking: Reframing the selective exposure debate. Journal of Communication, 59(4), 676–699. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01452.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC (2006). Narratives and cancer communication. Journal of Communication, 56(1), 163–S183. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, & Mcrobbie H (2014). Electronic cigarettes: Review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction, 109(11), 1801–1810. 10.1111/add.12659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, & Epton T (2010). The Impact of self-affirmation on health-related cognition and health behaviour: Issues and prospects. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(7), 439–454. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00270.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, & Napper L (2005). Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1250–1263. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinyard LJ, & Kreuter MW (2007). Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education & Behavior, 34(5), 777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell JL, Crosier BS, & Shepperd JA (2014). Does lacking threat-management resources increase information avoidance? A multi-sample, multi-method investigation. Journal of Research in Personality, 50, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels LT, Harris PR, Ruiter RA, & Klein WM (2016). Attentional effects of self-affirmation in response to graphic antismoking images. Health Psychology, 35(8), 891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, & Niederdeppe J (2016). Effects of self-affirmation, narratives, and informational messages in reducing unrealistic optimism about alcohol-related problems among college students. Human Communication Research, 42(2), 246–268. 10.1111/hcre.12073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WMP, Hamilton JG, Harris PR, & Han PKJ (2015). Health messaging to individuals who perceive ambiguity in health communications: The promise of self-affirmation. Journal of Health Communication, 20(5), 566–572. 10.1080/10810730.2014.999892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch‐Westerwick S, & Lavis SM (2017). Selecting serious or satirical, supporting or stirring news? Selective exposure to partisan versus mockery news online videos. Journal of Communication, 67(1), 54–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, ... & Clark EM. (2010). Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 81, S6–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Gottlieb JC, Cohen LM, & Trotter DR (2015). Electronic cigarette use among college students: Links to gender, race/ethnicity, smoking, and heavy drinking. Journal of American College Health, 63(8), 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu AS, Baranowski T, Thompson D, & Buday R (2012). Story immersion of videogames for youth health promotion: A review of literature. Games for Health: Research, Development, and Clinical Applications,1(3), 199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, & Klein WMP (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5, 289–354. doi: 10.1080/15298860600805325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monin B, Norton MI, Cooper J, & Hopg MA (2004). Reacting to an assumed situation vs. conforming to an assumed reaction: The role of perceived speaker attitude in vicarious dissonance. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 7(3), 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Moran MB, & Sussman S (2015). Changing attitudes toward smoking and smoking susceptibility through peer crowd targeting: more evidence from a controlled study. Health Communication, 30(5), 521–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SE, Movius L, & Cody MJ (2009). The power of narratives: The effect of entertainment television organ donation storylines on the attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of donors and nondonors. Journal of Communication, 59(1), 135–151. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01408.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé E (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, Moran MB, Zhao N, de Herrera PA, & Baezconde-Garbanati LA (2015). Comparing the relative efficacy of narrative vs nonnarrative health messages in reducing health disparities using a randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), pp. 2117–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, & Zhao X (2012). When does self-affirmation reduce negative responses to antismoking messages? Communication Studies, 63(4), 482–497. [Google Scholar]

- Napper L, Harris PR, & Epton T (2009). Developing and testing a self-affirmation manipulation. Self and Identity, 8(1), 45–62. 10.1080/15298860802079786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton MI, Monin B, Cooper J, & Hogg MA (2003). Vicarious dissonance: Attitude change from the inconsistency of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel P, Constance J, Guilbert P, Gautier A, Beck F, & Moatti JP (2007). Smoking too few cigarettes to be at risk? Smokers’ perceptions of risk and risk denial, a French survey. Tobacco Control, 16(5), 351–6. 10.1136/tc.2007.020362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persoskie A, Ferrer RA, Taber JM, Klein WMP, Parascandola M, & Harris PR (2015). Smoke-free air laws and quit attempts: Evidence for a moderating role of spontaneous self-affirmation. Social Science and Medicine, 141, 46–55. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish DA, Jensen S, & Johnson A (2008). A unified framework for addiction: Vulnerabilities in the decision process. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31(2008), 415–487. 10.1017/S0140525X0800472X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, & Aspinwall LG (1998). Self-affirmation reduces biased processing of health-risk information. Motivation and Emotion, 22(2), 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shen F, Sheer VC, & Li R (2015). Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advertising, 2, 105–113. 10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Hartson KA, Binning KR, Purdie-Vaughns V, Garcia J, Taborsky-Barba S, … Cohen GL (2013). Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: How self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 591–618. doi: 10.1037/a0031495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks P, & Jessop DC (2016). “Spontaneity is a meticulously prepared art” (Oscar Wilde): Commentary on Taber et al . (2016). Associations of spontaneous self-affirmation with health care experiences and health information seeking in a national survey of US adults. Psychology & Health, 31(April 2017), 310–312. 10.1080/08870446.2016.1145437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self In Berkowitz L (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 21: Social psychological studies of the self: Perspectives and programs (pp. 261–302). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Liu TJ (1983). Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 5–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney AM, & Moyer A (2015). Health psychology self-affirmation and responses to health messages: A meta-analysis on intentions and behavior self-affirmation and responses to health messages. Health Psychology, 34(2), 149–59. 10.1037/hea0000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber JM, Howell JL, Emanuel AS, Klein WMPP, Ferrer RA, & Harris PR (2015). Associations of spontaneous self-affirmation with health care experiences and health information seeking in a national survey of US adults. Psychology & Health, 446(October), 1–18. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1085986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber JM, Klein WMP, Ferrer RA, Kent EE, & Harris PR (2016a). Optimism and spontaneous self-affirmation are associated with lower likelihood of cognitive impairment and greater positive affect among cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(2), 198–209. 10.1007/s12160-015-9745-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor FR (2015). Tobacco, nicotine, and headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 55(7), 1028–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesser A (2000). On the confluence of self-esteem maintenance mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(4), 290–299. 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0404_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toma CL, & Hancock JT (2013). Self-affirmation underlies Facebook use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(3), 321–331. 10.1177/0146167212474694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukachinsky R, & Tokunaga RS (2013). The effects of engagement with entertainment. Communication Yearbook, 37, 287–322. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo CW, & Harper R (2013). Use and perception of electronic cigarettes among college students. Journal of American College Health, 61(3), 149–155. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.776052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2016). Trends in adolescent tobacco use. Retrieved from: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-health-topics/substance-abuse/tobacco/trends.html. Accessed November 12, 2016.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2016). FDA warns of health risks posed by e-cigarettes. Retrieved from: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm173401.htm. Accessed March 15, 2016.

- van Koningsbruggen GM, & Das E (2009). Don’t derogate this message! Self-affirmation promotes online type 2 diabetes risk test taking. Psychology & Health, 24(6), 635–649. 10.1080/08870440802340156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter N, Demetriades SZ, & Murphy ST (2016). Involved, united, and efficacious: Could self-affirmation be the solution to California’s drought? Health Communication, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzer MC, Cappella JN, Fishbein M, Hornik R, & Ahern RK (2003). The effectiveness of gateway communications in anti-marijuana campaigns. Journal of Health Communication, 8(2), 129–143. 10.1080/10810730305695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]