Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers can enhance the early and accurate etiologic detection of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) even when symptoms are very mild, but are not yet widely available for clinical testing. There are a number of reasons for this, including the need for an experienced operator, the use of instruments mostly reserved for research, and low cost-effectiveness when patient samples do not completely fill each assay plate. Newer technology can overcome some of these issues through automated assays of a single patient sample on existing clinical laboratory platforms, but it is not known how these newer automated assays compare with previous research-based measurements. This is a critical issue in the clinical translation of CSF AD biomarkers because most cohort and clinicopathologic studies have been analyzed on older assays. To determine the correlation of CSF beta-amyloid 1–42 (Aβ42) measures derived from the automated chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA, on Lumipulse® G1200), a bead-based Luminex immunoassay, and a plate-based enzyme-linked immunoassay enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), we analyzed 30 CSF samples weekly on each platforms over 3 weeks. We found that, while CSF Aβ42 levels were numerically closer between CLEIA and ELISA measurements, levels differed between all three assays. CLEIA-based measures correlated linearly with the two other assays in the low and intermediate Aβ42 concentrations, while there was a linear correlation between Luminex assay and ELISA throughout all concentrations. For repeatability, the average intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 2.0%. For intermediate precision, the inter-assay CV was lower in CLEIA (7.1%) than Luminex (10.7%, p = 0.009) and ELISA (10.8%, p = 0.009), primarily due to improved intermediate precision in the higher CSF Aβ42 concentrations. We conclude that the automated CLEIA generated reproducible CSF Aβ42 measures with improved intermediate precision over experienced operators using Luminex assays and ELISA, and are highly correlated with the manual Aβ42 measures.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, biomarkers, cerebrospinal fluid, mild cognitive impairment, intermediate precision

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of proteins and peptides associated with neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles can enhance the accurate etiologic diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Shaw et al., 2009; Jack et al., 2010, 2018). These markers –beta-amyloid peptides (Aβ38, Aβ40, Aβ42), (Adamczuk et al., 2015; Olsson et al., 2016; Howell et al., 2017) total and phosphorylated tau (Arai et al., 2000; Hampel et al., 2004; Fagan et al., 2009) – are measured in research and commercial laboratories around the world, but there remain key obstacles in their broader application. These include the need to purchase a research-based assay platform, pre-analytical and analytical variability, (Fourier et al., 2015; Leitao et al., 2015) and the need for experienced operators. While international quality control programs (Toledo et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2013; Pannee et al., 2016) aim to optimize measurement variability across assays, reagents, platforms, standards, operators, and algorithms, technological solutions including process engineering and assay automation can potentially reduce variability introduced by human operators that influence assay performance.

Immunoassays targeting Aβ42, t-Tau, and p-Tau181 have predominated the landscape of CSF AD biomarker analysis to date, although mass spectrometry-based assays are under development (Pannee et al., 2016). Compared to solid-phase enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and fluid-phase Luminex assays which require manual reagent addition and removal on multi-well plates, automated analyzers are proposed to have better repeatability (variability within the same assay) and intermediate precision (variability between different assays). The Fujirebio Lumipulse® system and the Roche Elecsys® have shown consistent inter-assay measures in the serum, with coefficient of variation (CV) in the range of 1.2–10% for hepatitis B antigens, (Yang et al., 2016) tumor markers, (Marlet and Bernard, 2016) cortisol, (Vogeser et al., 2017) and interleukin-13 (Palme et al., 2017). In the CSF, a recent multi-center study using synthetic Aβ42 peptides in artificial CSF reported inter-assay CV of <5% on the Elecys® system, (Bittner et al., 2016) but the intermediate precision of endogenous Aβ42 in human-derived CSF samples in these automated analyzers remains unknown. Because most cohort, (Ellis et al., 2009; Shaw et al., 2009; Bendlin et al., 2012) clinicopathologic, (Roher et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010; Li et al., 2015) and pharmacological (Blennow et al., 2012; Kennedy et al., 2016) studies to-date have relied on one of the non-automated assays, it is also important to determine the measurement correlation between the three assay formats. Here we selected 30 human CSF samples representing a range of physiologic Aβ42 levels, characterized the correlation between CSF Aβ42 measurements from different assay types, and assessed the repeatability and intermediate precision of each assay.

Materials and Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals and Patient Consents

This study was carried out in accordance to US Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Part 46 Protection of Human Subjects, and Emory University and Emory School of Medicine policies. The protocols were approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Banked CSF samples were used for this study, and all subjects had previously given written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki for long-term sample storage and future analysis.

CSF Pooling and Aliquotting

Cerebrospinal fluid samples were all previously collected using a modified AD Neuroimaging Initiative protocol (Hu et al., 2013). Briefly, CSF was collected into 15 mL polypropylene tubes via a 24-gauge atraumatic needle and syringe aspiration without overnight fasting. Polypropylene tubes were inverted several times, and CSF was aliquotted (500 μL), labeled, and frozen at -80°C until analysis.

Cerebrospinal fluid samples from 30 subjects were selected for the study (Table 1). Subjects were chosen to represent a wide range of Aβ42 concentrations (previously measured using Luminex): nine had normal cognition, 12 had mild cognitive impairment, six had AD dementia, and three had other non-AD dementias (one each for corticobasal syndrome, dementia with Lewy bodies, and progressive supranuclear palsy).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects and assays according to CSF Aβ42 concentrations.

| Low(n = 10) | Intermediate(n = 10) | High(n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) |

| Age, yr (SD) | 72.7 (7.9) | 65.5 (8.5) | 72.5 (8.4) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Normal cognition | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| AD dementia | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Other dementia | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Aβ42CLEIA, pg/mL (SD) | 219.5 (50.2) | 327.7 (51.0) | 821.5 (194.4) |

| Aβ42Luminex, pg/mL (SD) | 105.7 (29.3) | 173.3 (42.4) | 400.9 (68.6) |

| Aβ42ELISA, pg/mL (SD) | 265.9 (56.6) | 363.3 (66.1) | 698.0 (97.6) |

| t-TauLuminex, pg/mL (SD) | 51.2 (50.9) | 64.3 (62.1) | 33.5 (7.8) |

| p-TauLuminex, pg/mL (SD) | 22.9 (24.7) | 42.2 (48.8) | 7.1 (6.9) |

| Intra-assay CV (repeatability) | |||

| CLEIA | 2.4% | 2.1% | 1.4% |

| Luminex | 12.0% | 13.3% | 9.4% |

| ELISA | 3.3% | 3.6% | 3.1% |

| Inter-assay CV (intermediate precision) | |||

| CLEIA | 10.1% | 7.1% | 4.0% |

| Luminex | 11.8% | 11.5% | 8.8% |

| ELISA | 14.6% | 9.8% | 7.8% |

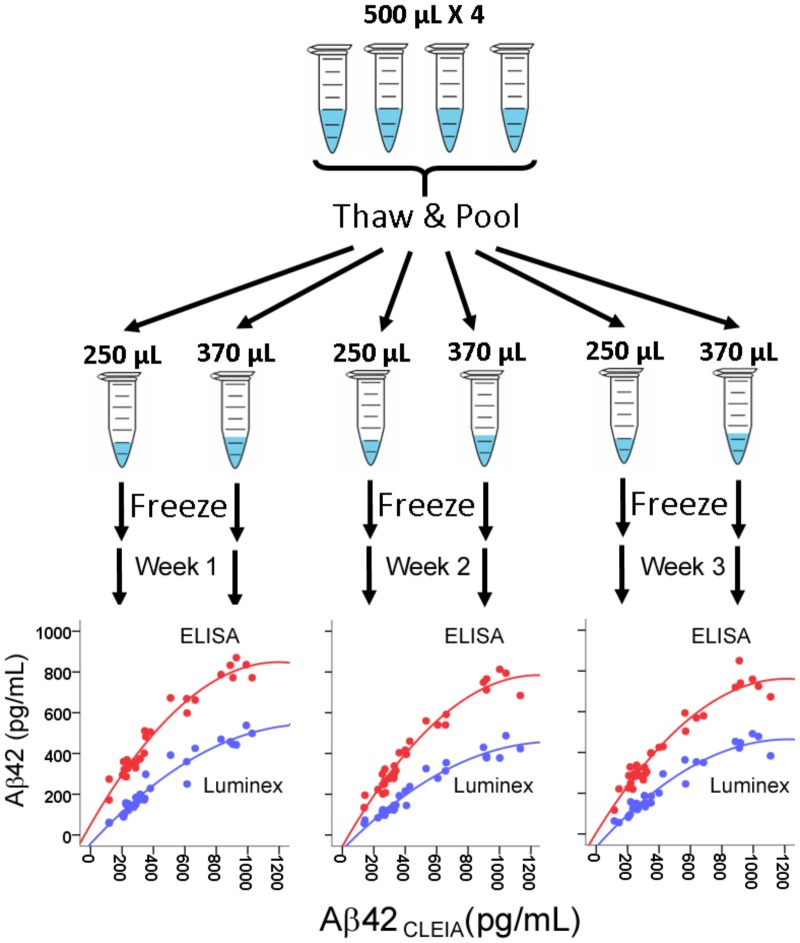

Because we wished to compare the platforms’ performance over three weekly runs, we first generated identical CSF aliquots for all runs (Figure 1). For each subjects, four 500 μL CSF aliquots were thawed at room temperature, vortexed, and pooled into a 5 mL polypropylene tube. The pooled 2 mL aliquot was then vortexed and separated into three 250 μL aliquots and three 370 μL aliquots. All aliquots were then re-frozen to ensure the same freeze-thaw cycles in addition to the same number of tube transfers.

FIGURE 1.

Assessment of correlation between CSF Aβ42 levels measured in CLEIA, Luminex, and ELISA across three weekly runs. For each subject, four frozen 500 μL aliquots were thawed, pooled, and realiquoted. On the first day of each week, aliquots were thawed for analysis on the three platforms. In the correlational figures, CLEIA measures are presented on the X-axis, and the ELISA and Luminex measures are presented on the Y-axis.

CSF Analysis

On the first day of each study week, every sample was analyzed in triplicates (three wells) on the automated Lumipulse® Aβ42 chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA), INNO-Bia Alzbio3 Luminex assay, and INNOTEST® Aβ42 ELISA. In the morning, one 370 μL aliquot was thawed at room temperature for each subject and analyzed using the ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol on two separate 96-well plates. A full set of kit standards and two kit controls were included in each plate. The inter-plate CV for the kit controls were 4.7 and 18.0% on Week 1, 2.9, and 4.8% on Week 2, and 21.6 and 13.4% on Week 3. The remaining CSF from each 370 μL aliquot was transferred to the CLEIA sample cups for Aβ42 analysis following the manufacturer’s protocol.

In the afternoon, one 250 μL aliquot was thawed at room temperature for Luminex assays according to a modified manufacturer’s protocol: all samples were vortexed vigorously for exactly 15 s immediately prior to plate loading, (Hu et al., 2015) and the bead count (performed the next day) was reduced to 75 to minimize fluorescence loss. As with the ELISA, samples were divided between two plates, with a full set of kit standards and two kit controls on each plate. The inter-plate CVs for the two kit controls were 0.2 and 0.9% on Week 1, 6.1 and 2.8% on Week 2, and 4.7 and 1.9% on Week 3.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 24.0 (Armonk, NY, United States). Aβ42 concentrations measured by CLEIA, Luminex, and ELISA were all log-transformed prior to Pearson’s correlation analysis due to their non-normal distribution, with p < 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons. Repeatability for each assay was assessed by averaging CV for the triplicate concentration values within the same run, and intermediate precision for each assay was assessed by calculating CV for the three weekly concentrations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) were used to determine whether intermediate precision differed between the three assays before and after adjusting for Log10-transformed concentrations.

Data Availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Results

Aβ42 Levels Were Highly Correlated Between the Three Assays

There was a very high degree of correlation between concentrations from all three platforms (R = 0.964–0.973 between CLEIA and Luminex, 0.961–0.967 between CLEIA and ELISA, and 0.932–0.969 between Luminex and ELISA). Regression analysis showed that a quadratic – rather than linear – relationship better converted measures from ELISA and Luminex to CLEIA due to relatively higher CLEIA measures than ELISA/Luminex measures in the high concentration range [Figure 1, Aβ42CLEIA = 63.32 + 0.32Aβ42ELISA + 0.001Aβ42ELISA2, Aβ42CLEIA = 100 + 0.92Aβ42Luminex + 0.002Aβ42Luminex2]. In contrast, the relationship between Luminex and ELISA was linear in all concentrations (Aβ42Luminex = 0.66Aβ42ELISA -66.35).

Repeatability

The average intra-assay CV for Aβ42CLEIA was <2.5% for all Aβ42 levels (Table 1). These were comparable to values for Aβ42ELISA, but lower than values for Aβ42Luminex as expected from the reduced bead count per well. Among 90 triplicates, two samples (2%, from the same subject) on CLEIA and five samples from ELISA had intra-assay CV greater than 5%.

Intermediate Precision

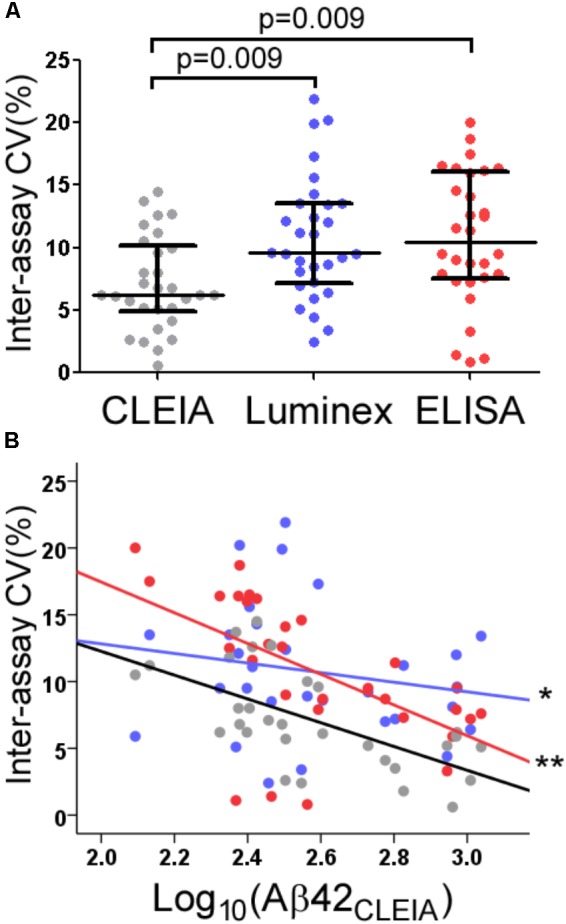

The average inter-assay (within laboratory) CV for Aβ42CLEIA ranged from 4.0% for high concentrations to 10.1% for low concentrations (Table 1). When all concentrations were analyzed together, ANOVA showed that Aβ42CLEIA (7.1%) had lower inter-assay CV than the other platforms [Figure 2A, 10.7% for Aβ42Luminex (p = 0.0090), 10.8% for Aβ42ELISA (p = 0.009)]. ANCOVA adjusting for Aβ42CLEIA concentrations (Figure 2B) showed that, in addition to an inverse relationship between CV and concentration (p < 0.001), CLEIA had greater intermediate precision than Luminex at higher concentrations (p = 0.001 for assay X concentration), and greater intermediate precision over ELISA at all concentrations (p < 0.001 for assay).

FIGURE 2.

Intermediate precision of CLEIA-, Luminex-, and ELISA-based CSF Aβ42 measures. Across all concentrations, Aβ42CLEIA measures had lower CV than Aβ42Luminex or Aβ42ELISA (A). Further examination of the differences in CV (B) showed that Aβ42CLEIA had lower inter-assay CV than Aβ42Luminex at higher concentrations (∗), and Aβ42ELISA at all concentrations (∗∗).

Discussion

While CSF biomarkers have shown great promise in the ante-mortem prediction of AD pathology, pre-analytical and analytical processes need to be standardized and simplified for inclusion into existing clinical workflows. Because every step – pre-analytical or analytical – affords an opportunity for within-operator and between-operator variability, automation of the analytical portion of Aβ42 measurements likely reduced the within-operator, inter-assay imprecision (Bittner et al., 2016; Chiasserini et al., 2016). Operator-associated imprecision in the busy clinical laboratories is likely much greater, as published inter-assay CV values generally come from experienced biomarker laboratories (5.3–14% for Luminex and 6.4–25% for ELISA) with experienced staff dedicated to these specialized assays (Kang et al., 2013). At the same time, inconsistent reporting of intermediate precision – particularly related to source material [e.g., synthetic peptides, (Bittner et al., 2016) pooled CSF (Chiasserini et al., 2016)] – prevents comparison across manual and automated platforms, as well as across different automated platforms. While the study design here required a modest amount of CSF from each subject, involving banked samples from multiple centers or recruiting study volunteers specifically for the purpose of assay standardization can streamline future studies for new assays or analyzers.

The strong correlation between Aβ42CLEIA and the other Aβ42 measures also permits comparison between legacy and new data. The correlation observed here is stronger than that reported between another automated analyzer and the same ELISA we used (Chiasserini et al., 2016). The difference likely resulted from our use of CLEIA and ELISA from the same manufacturer. Our observation of non-linear relationship in higher Aβ42 concentrations also warrants follow-up, as this observation was not specifically examined with the other analyzers. Nevertheless, we report good repeatability, intermediate precision, and strong correlation with established Aβ42 assays. Because the automated analyzer already has FDA clearance in the United States, CSF Aβ42 measurement will likely not be limited to specialized centers in the near future. At the same time, because CSF collection and handling are still manual in nature, there is an ever more urgent need to standardize these pre-analytical steps through processing engineering and possibly automation.

Author Contributions

AK, JH, and WH contributed conception and design of the study. AK and JH organized the dataset. AK and WH performed the statistical analysis. AK, JH, and WH wrote sections of the manuscript, contributed to the revision of the manuscript, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

WH has a patent on the use of CSF biomarkers to diagnose FTLD-TDP (US 9,618,522); has received research support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (Philadelphia, PA, United States) and Fujirebio US (Malvern, PA, United States); serves as a consultant to AARP, Inc., Locks Law Firm, Interpleader Law, and ViveBio LLC; has received travel support from Hoffman-LaRoche and Abbvie. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was sponsored by Emory University and Fujirebio US. Fujirebio US has no role in the study design, data analysis, the decision to submit for publication, or writing/editing of the manuscript.

References

- Adamczuk K., Schaeverbeke J., Vanderstichele H. M., Lilja J., Nelissen N., Van Laere K., et al. (2015). Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid Abeta ratios in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 7:75. 10.1186/s13195-015-0159-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Ishiguro K., Ohno H., Moriyama M., Itoh N., Okamura N., et al. (2000). CSF phosphorylated tau protein and mild cognitive impairment: a prospective study. Exp. Neurol. 166 201–203. 10.1006/exnr.2000.7501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlin B. B., Carlsson C. M., Johnson S. C., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Willette A. A., et al. (2012). CSF T-Tau/Abeta42 predicts white matter microstructure in healthy adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 7:e37720. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner T., Zetterberg H., Teunissen C. E., Ostlund R. E., Jr., Militello M., Andreasson U., et al. (2016). Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of beta-amyloid (1–42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Dement. 12 517–526. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K., Zetterberg H., Rinne J. O., Salloway S., Wei J., Black R., et al. (2012). Effect of immunotherapy with bapineuzumab on cerebrospinal fluid biomarker levels in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 69 1002–1010. 10.1001/archneurol.2012.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasserini D., Biscetti L., Farotti L., Eusebi P., Salvadori N., Lisetti V., et al. (2016). Performance evaluation of an automated ELISA system for Alzheimer’s disease detection in clinical routine. J. Alzheimers Dis. 54 55–67. 10.3233/JAD-160298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis K. A., Bush A. I., Darby D., De Fazio D., Foster J., Hudson P., et al. (2009). The Australian imaging, biomarkers and lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging: methodology and baseline characteristics of 1112 individuals recruited for a longitudinal study of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 21 672–687. 10.1017/S1041610209009405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan A. M., Mintun M. A., Shah A. R., Aldea P., Roe C. M., Mach R. H., et al. (2009). Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 1 371–380. 10.1002/emmm.200900048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourier A., Portelius E., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Quadrio I., Perret-Liaudet A. (2015). Pre-analytical and analytical factors influencing Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker variability. Clin. Chim. Acta 449 9–15. 10.1016/j.cca.2015.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H., Buerger K., Zinkowski R., Teipel S. J., Goernitz A., Andreasen N., et al. (2004). Measurement of phosphorylated tau epitopes in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: a comparative cerebrospinal fluid study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 61 95–102. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell J. C., Watts K. D., Parker M. W., Wu J., Kollhoff A., Wingo T. S., et al. (2017). Race modifies the relationship between cognition and Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 9:88. 10.1186/s13195-017-0315-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. T., Chen-Plotkin A., Arnold S. E., Grossman M., Clark C. M., Shaw L. M., et al. (2010). Novel CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol. 119 669–678. 10.1007/s00401-010-0667-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. T., Watts K., Grossman M., Glass J., Lah J. J., Hales C., et al. (2013). Reduced CSF p-Tau181 to Tau ratio is a biomarker for FTLD-TDP. Neurology 81 1945–1952. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436625.63650.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. T., Watts K. D., Shaw L. M., Howell J. C., Trojanowski J. Q., Basra S., et al. (2015). CSF beta-amyloid 1–42 – what are we measuring in Alzheimer’s disease? Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2 131–139. 10.1002/acn3.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C. R., Jr., Bennett D. A., Blennow K., Carrillo M. C., Dunn B., Haeberlein S. B., et al. (2018). NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14 535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C. R., Jr., Knopman D. S., Jagust W. J., Shaw L. M., Aisen P. S., Weiner M. W. et al. (2010). Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 9 119–128. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. H., Korecka M., Toledo J. B., Trojanowski J. Q., Shaw L. M. (2013). Clinical utility and analytical challenges in measurement of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta(1–42) and tau proteins as Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Clin. Chem. 59 903–916. 10.1373/clinchem.2013.202937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M. E., Stamford A. W., Chen X., Cox K., Cumming J. N., Dockendorf M. F., et al. (2016). The BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat (MK-8931) reduces CNS beta-amyloid in animal models and in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 8:363ra150. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad9704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao M. J., Baldeiras I., Herukka S. K., Pikkarainen M., Leinonen V., Simonsen A. H., et al. (2015). Chasing the effects of pre-analytical confounders-a multicenter study on CSF-AD biomarkers. Front. Neurol. 6:153. 10.3389/fneur.2015.00153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. X., Villemagne V. L., Doecke J. D., Rembach A., Sarros S., Varghese S., et al. (2015). Alzheimer’s disease normative cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers validated in PET Amyloid-beta characterized subjects from the Australian imaging, biomarkers and lifestyle (AIBL) study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 48 175–187. 10.3233/JAD-150247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlet J., Bernard M. (2016). Comparison of LUMIPULSE((R)) G1200 with kryptor and modular E170 for the measurement of seven tumor markers. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 30 5–12. 10.1002/jcla.21802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson B., Lautner R., Andreasson U., Öhrfelt A., Portelius E., Bjerke M., et al. (2016). CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 15 673–684. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palme S., Christenson R. H., Jortani S. A., Ostlund R. E., Kolm R., Kopal G., et al. (2017). Multicenter evaluation of analytical characteristics of the Elecsys((R)) Periostin immunoassay. Clin. Biochem. 50 139–144. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannee J., Gobom J., Shaw L. M., Korecka M., Chambers E. E., Lame M., et al. (2016). Round robin test on quantification of amyloid-beta 1–42 in cerebrospinal fluid by mass spectrometry. Alzheimers Dement. 12 55–59. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.06.1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roher A. E., Maarouf C. L., Sue L. I., Hu Y., Wilson J., Beach T. G. (2009). Proteomics-derived cerebrospinal fluid markers of autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Biomarkers 14 493–501. 10.3109/13547500903108423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw L. M., Vanderstichele H., Knapik-Czajka M., Clark C. M., Aisen P. S., Petersen R. C., et al. (2009). Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann. Neurol. 65 403–413. 10.1002/ana.21610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo J. B., Brettschneider J., Grossman M., Arnold S. E., Hu W. T., Xie S. X., et al. (2012). CSF biomarkers cutoffs: the importance of coincident neuropathological diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 124 23-35. 10.1007/s00401-012-0983-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeser M., Kratzsch J., Ju Bae Y., Bruegel M., Ceglarek U., Fiers T., et al. (2017). Multicenter performance evaluation of a second generation cortisol assay. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 55 826–835. 10.1515/cclm-2016-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Song G., Guan W., Wang Q., Liu Y., Wei L. (2016). The lumipulse G HBsAg-Quant assay for screening and quantification of the hepatitis B surface antigen. J. Virol. Methods 228 39–47. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.