Metagenomic shotgun sequencing has the potential to transform how serious infections are diagnosed by offering universal, culture-free pathogen detection. This may be especially advantageous for microbial diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) by synovial fluid analysis since synovial fluid cultures are not universally positive and since synovial fluid is easily obtained preoperatively.

KEYWORDS: (molecular) diagnostics, (peri)prosthetic joint infection/joint infection, metagenomics, next-generation sequencing, synovial fluid

ABSTRACT

Metagenomic shotgun sequencing has the potential to transform how serious infections are diagnosed by offering universal, culture-free pathogen detection. This may be especially advantageous for microbial diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) by synovial fluid analysis since synovial fluid cultures are not universally positive and since synovial fluid is easily obtained preoperatively. We applied a metagenomics-based approach to synovial fluid in an attempt to detect microorganisms in 168 failed total knee arthroplasties. Genus- and species-level analyses of metagenomic sequencing yielded the known pathogen in 74 (90%) and 68 (83%) of the 82 culture-positive PJIs analyzed, respectively, with testing of two (2%) and three (4%) samples, respectively, yielding additional pathogens not detected by culture. For the 25 culture-negative PJIs tested, genus- and species-level analyses yielded 19 (76%) and 21 (84%) samples with insignificant findings, respectively, and 6 (24%) and 4 (16%) with potential pathogens detected, respectively. Genus- and species-level analyses of the 60 culture-negative aseptic failure cases yielded 53 (88%) and 56 (93%) cases with insignificant findings and 7 (12%) and 4 (7%) with potential clinically significant organisms detected, respectively. There was one case of aseptic failure with synovial fluid culture growth; metagenomic analysis showed insignificant findings, suggesting possible synovial fluid culture contamination. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing can detect pathogens involved in PJI when applied to synovial fluid and may be particularly useful for culture-negative cases.

INTRODUCTION

Preoperative diagnosis and identification of pathogens involved in prosthetic joint infection (PJI) represent a challenge as up to 40% of cases which meet diagnostic criteria for PJI are synovial fluid culture negative (1, 2). Treatment of PJI is accomplished through targeted surgical and antimicrobial management, which is contingent on accurate diagnosis and pathogen identification, ideally preoperatively. This is complicated by the wide array of pathogens implicated in PJI, alongside the often low organism burden, deleterious effects of previous antimicrobial treatment, potentially undetected polymicrobial infection, and infection by fastidious organisms (3, 4). Clinical management in the absence of identified etiology drives up the use of empirical, broad-spectrum antibiotics in an attempt to encompass all possible pathogens and thus risks not treating an organism present and even missing actual PJI cases.

Metagenomic shotgun sequencing, utilizing next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, refers to a technique where all the nucleic acids present in a specimen, including those deriving from the host as well as from any microorganism(s) present, are sequenced in parallel. Through assembly and analysis, this approach allows detection and identification of microorganism(s) without the need for a priori knowledge. This type of microbe-agnostic approach, in combination with comprehensive reference databases, has the potential to address diagnostic challenges and define the etiology of culture-negative infections, including PJI, through unbiased, culture-free pathogen detection.

Metagenomic shotgun sequencing has been successfully applied to a range of clinical specimens for the purpose of defining infectious etiology; specimens derived from infections of the central nervous system (5–14), respiratory system (15–17), eye (18), blood (19–22), and gastrointestinal tract (23, 24), as well as those from bone and joint infection (25–27), have been studied. Applying this technique to synovial fluid, a specimen type which is easily obtained preoperatively for diagnosis of PJI, has potential for clinical impact. Successful analysis of synovial fluid, collected preoperatively, would permit targeted surgical management and antibiotic administration. As a result, this could lead to a reduction in diagnostic uncertainty and cost of care. Additionally, this approach has demonstrated potential for novel organism discovery (28). It also offers an advantage over bacterial 16S rRNA gene PCR/sequencing (by Sanger sequencing or NGS), which may miss the causative pathogen if it is fungal, viral, or parasitic in origin.

With the advent of metagenomic shotgun sequencing for rapid infectious disease diagnosis, there are new limitations that must be addressed. Given the unbiased approach and potential breadth of detection by metagenomic sequencing, the impact of host and contaminating nucleic acids has been shown to critically impact downstream results and analysis (29–32). This issue becomes particularly relevant for samples containing low bioburdens or where there is lack of an obvious pathogen, such as synovial fluid (29). Specimens, therefore, require proper handling, avoiding the introduction of stray microbial nucleic acids, and results require careful analysis and interpretation.

By means of this study, we sought to better define the microbial etiology of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) failure using metagenomic shotgun sequencing applied directly to synovial fluid. In the largest series to date, we report the results of metagenomic analysis of 168 synovial fluid samples aspirated from the site of TKA. The samples included in this data set were processed and sequenced regardless of microbial DNA concentration to provide an accurate representation of the data that would likely be obtained from metagenomic analysis of synovial fluid in clinical settings. In addition, specialized sample processing (i.e., microbial enrichment and deep sequencing), custom bioinformatics data analysis (utilizing multiple algorithms for taxonomic assignment [k-mer and marker-based analysis] and alignment of reads to the reference genome of the pathogen), and use of negative controls to determine the nucleic acid background of the reagents were employed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects.

A total of 168 synovial fluid samples collected from subjects with culture-positive PJIs, culture-negative PJIs, or aseptic implant failures between April 1998 and June 2017 were selected from a biobank of aspirated synovial fluid stored at −80°C in vials that were pretreated with gamma irradiation to minimize DNA contamination; synovial fluid was collected with patient informed consent under Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board protocol 10-005574 at the time of routine clinical preoperative arthrocentesis. Results from cell count and differential, performed as part of routine clinical practice, were available for 160 of 168 synovial fluid specimens. A total of 159 of 168 subjects proceeded to surgical intervention, yielding operative data (e.g., periprosthetic tissue culture and histopathologic examination, assessment of intra-articular purulence, sonicate fluid culture) for evaluation.

Patient classification.

Patients were classified as having aseptic failure or PJI based on Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) PJI diagnostic criteria (4). Eleven cases, which did not meet IDSA PJI diagnostic criteria, were classified as PJI following blinded review of all preoperative and intraoperative information by an infectious disease physician. Clinical review data for classification are indicated in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Synovial fluid culture.

For synovial fluid culture, volumes of ≥1 ml were inoculated into a BD Bactec Peds Plus/F bottle and incubated for 5 days on a Bactec 9240 instrument prior to November 2012 and on a Bactec FX instrument (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) after November 2012. Blood culture bottles signaling positively underwent Gram staining and subculture. Synovial fluid samples with a volume of <1 ml were inoculated onto BBL Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 5% sheep blood agar and BBL Chocolate II agar, which was followed by incubation at 35 to 37°C in 5 to 7% CO2 for 2 to 5 days, and into BBL fluid thioglycolate medium (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD), which was followed by incubation at 35 to 37°C for 5 days. Cloudy thioglycolate broths underwent Gram staining and were subcultured. Positive plate results were semiquantitatively reported. When anaerobic culture was requested, which was typically the case, anaerobic Remel thioglycolate broth without indicator with vitamin K and hemin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS) was inoculated and incubated for 7 to 14 days, and BBL Centers for Disease Control and Prevention anaerobe 5% sheep blood agar (BD Diagnostic Systems) was inoculated and incubated anaerobically at 35 to 37°C for 7 to 14 days. Any growth from synovial fluid was considered culture positive, and no growth from synovial fluid was considered culture negative.

Sample preparation for metagenomic shotgun whole-genome sequencing.

Metagenomic methods were adopted from Thoendel et al. (33). Sample preparation was conducted in a laminar flow hood, and work areas were thoroughly cleaned with 5% bleach solution before and after each specimen was processed. Prior to DNA extraction, 1 ml of synovial fluid underwent microbial DNA enrichment using a MolYsis Basic5 kit (Molzym, Bremen, Germany), which selectively lyses human cells via a chaotropic buffer treatment. The released human DNA was then degraded by MolDNase, which is active in the presence of chaotropes in the lysis buffer. Bacteria present in the specimen were then pelleted, washed, and subjected to DNA extraction and isolation using a MoBio Bacteremia DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Whole-genome amplification (WGA) was then carried out using a Qiagen REPLI-g Single Cell kit (Qiagen), per the manufacturer's instructions, with the exception that reaction mixture volumes were half the recommended size. Amplified DNA was purified using Agencourt Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) per the manufacturer's protocol with elution in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, pH 8.0 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 suspended in Ringer's solution at 105 CFU was used as an external positive control. TE buffer, pH 8.0 (Integrated DNA Technologies), subjected to sample preparation and sequenced alongside synovial fluid samples, was included as a negative control for the final two sequenced batches (49 samples). WGA reactions run without addition of DNA template were also included as negative controls for every sequencing batch.

Library preparation and Illumina HiSeq sequencing.

Paired-end libraries from WGA reactions were prepared using a NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) by the Mayo Clinic Medical Genome Facility. Samples were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument in rapid-run mode with paired-end reads at 250 cycles and multiplexed with six samples per lane. This yielded an average of 30,013,446 paired-end reads (range, 17,119,865 to 47,181,879 reads) of 500 bp in length per sample.

Bioinformatics pipeline.

Metagenomic analysis was performed using a pipeline that incorporated multiple publicly available tools and that is available for download. Trimmomatic (version 0.36) was used to remove Illumina adapter sequences (34). BioBloom Tools (version 2.0.12) was then used to filter out residual human and PhiX sequences (35). The remaining paired-end reads were merged and assigned to taxonomic groups by the k-mer-based classification software Livermore Metagenomics Analysis Toolkit (LMAT; version 1.2.6) (36). A minimum read label score of 1.0 was selected as this is considered a high-confidence identification. An additional marker-gene-based classification software program, MetaPhlAn2, was then used to analyze trimmed reads (37).

Data analysis.

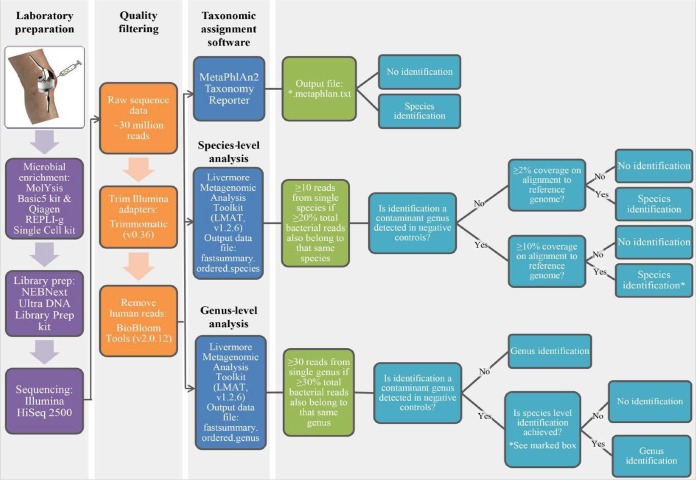

The performance of metagenomic sequencing was assessed by separately comparing genus and species identifications made by metagenomic analysis to the pathogen(s) isolated from synovial fluid culture. To correct for samples containing low-level background DNA and nonspecific microbial reads, genus- and species-level thresholds for the number of reads, percentage of reads as a proportion of all microbial reads present, and percentage of genome coverage on alignment to a reference genome, achieved using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA; version 0.7.1 [https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997]) with coverage statistics reported by BBMap (version 37.24 [https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/]), were established (38). Stricter thresholds were applied to contaminant genera detected in sequenced negative controls. Thresholds were established based on observable patterns of ground truth data and have yet to be tested in a second validation data set. The workflow following library preparation and the bioinformatics pipeline and analysis performed in this study to yield true positive identifications are depicted in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Workflow, including specimen preparation and bioinformatics analysis, performed in this study.

To define the nucleic acid backgrounds of the reagents used for sample preparation, negative controls (TE buffer, pH 8.0) were sequenced alongside synovial fluid specimens, and a list of contaminant identifications was established based on two sequencing runs. A single genus with ≥1,000 read identifications was considered relevant (Table 1). Streptococcus species was identified with 8,685 reads but was removed from the list due to consistent poor genome recovery in cases of true infection. In addition, Bradyrhizobium species was added to the list based on a number of reports in the literature suggesting it to be a ubiquitous contaminant (29, 31, 32) and on its frequent detection in our data. Reads successfully assigned by LMAT to the genus and species level were examined independently using ordered genus and ordered species output data files, respectively. Contaminant genera detected in sequenced negative controls were subject to stricter species-level thresholds. Identifications for species belonging to contaminant genera that met or surpassed the stricter threshold were listed as potential pathogens. Chromosomal reads from Staphylococcus lugdunensis mistakenly assigned as plasmid reads were manually added to the ordered species data file. No other obvious misassignments were observed. The percentage of reads was recalculated to the percentage of total microbial reads by removing human, viral, synthetic, plasmid, and phage reads. A series of thresholds were then applied using a novel filtering strategy to identify true infection.

TABLE 1.

List of contaminant genera detected in negative controls

| Read count | Genusa | Previous report(s)b |

|---|---|---|

| 2,017,563 | Acinetobacter | 29, 42, 44, 45 |

| 542,456 | Alishewanella | |

| 386,476 | Ralstonia | 29, 31, 45, 46 |

| 186,721 | Anaerococcus | 26, 42 |

| 100,847 | Haemophilus | 42 |

| 23,008 | Malassezia | 42 |

| 16,734 | Enhydrobacter | 29 |

| 14,034 | Sphingomonas | 29, 31, 45 |

| 3,705 | Paenibacillus | |

| 3,338 | Delftia | 29, 42 |

| 3,179 | Corynebacterium | 25, 29, 42 |

| 2,669 | Cutibacterium | 25, 26, 29, 42 |

| Bradyrhizobiumc | 29, 31, 32 |

The listed genera were detected with ≥1,000 read identifications in sequenced negative controls processed alongside human-derived samples. Streptococcus was removed from the list due to consistently poor genome recovery in cases of true infection.

Genus has also been reported as a contaminant or identified as a false-positive finding by other investigators.

Bradyrhizobium was added to the list based on a number of findings in literature reporting it as a ubiquitous contaminant.

LMAT species-level analysis.

For species identifications, one threshold including three parameters (a to c) was used to determine true infection; the third parameter (c) increased for species belonging to a genus group that was previously identified as a contaminant detected in sequenced negative controls. A species was considered positive if it reached or exceeded (a) a lower-read cutoff for species-specific reads, (b) a percentage cutoff for species-specific reads as a proportion of all microbial reads present, and (c) a percentage cutoff for base pair coverage as determined on alignment to a reference genome. LMAT read classifications at the species level are listed for every sample in Table S2. These results were recalculated to the exclusion of all human, viral, synthetic, plasmid, and phage reads in Table S3.

LMAT genus-level analysis.

For genus identifications, one threshold including two parameters (a and b) was used to determine true infection; a third parameter (c) was applied to genera identified as a contaminant detected in sequenced negative controls. A genus was considered positive if it reached or exceeded (a) a lower-read cutoff for genus-specific reads and (b) a percentage cutoff for genus-specific reads as a proportion of all microbial reads present. Contaminant genera with species-level identification, meeting all three contaminant-specific parameters (c), were considered positive. LMAT read classifications at the genus level are listed for every sample in Table S4. These results were recalculated to the exclusion of all human, viral, synthetic, plasmid, and phage reads in Table S5. The complete taxonomic rank for identifications made by LMAT is listed for every sample in Table S6.

MetaPhlAn2 analysis.

Identifications made by the marker-gene classification software, MetaPhlAn2, were examined in addition to LMAT. Successful classification reported in the output file, SF#.metaphlan.txt, was used to determine true infection. All species-level bacterial and fungal identifications were considered positive. Identifications for family, genus, or unclassified reporting were considered negative.

Accession number(s).

Human reads were removed, and the raw sequence data for each sample were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject accession number PRJNA436717.

RESULTS

Patient classification and characteristics.

A total of 168 synovial fluid samples aspirated from the site of total knee arthroplasty were evaluated using metagenomic shotgun sequencing. This included 96 samples classified as infected by IDSA guidelines as PJI, 11 additional cases classified as infected by clinical review, and another 61 classified as aseptic failure. Subject demographics, classification criteria, and clinically relevant findings, including laboratory tests, are summarized in Table 2, with individual details provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of study subjects

| Parameter | Value by groupa |

|

|---|---|---|

| Aseptic failure (n = 61) | PJI (n = 107) | |

| Mean age (range [yr]) | 68.3 (34–89) | 66.3 (43–88) |

| No. of males (%) | 29 (47.5%) | 69 (64.5%) |

| Mean BMI (range) | 32.6 (19.59–54.57) | 33.3 (17.43–60.24) |

| No. of patients who underwent surgical management | 60 | 99 |

| IDSA PJI criteria (no. of patients) | ||

| Purulence | 0 | 78 |

| Sinus tract | 0 | 17 |

| Identical organism identified with two separate cultures | 0 | 82 |

| Acute inflammation on histopathology (no. of patients positive/total no. of patients) | 1/56 | 71/90 |

| Antibiotics within 4 weeks prior to aspiration (no. of patients) | 4 | 46 |

| Laboratory parameters (no. of patients positive/total no. of patients) | ||

| Synovial fluid cell count >1,700 cells/μl | 24/61 | 93/100 |

| Synovial fluid neutrophil percentage >65% | 5/60 | 93/100 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥30 mm/h | 8/60 | 76/103 |

| C-reactive protein ≥10 mg/liter | 13/59 | 85/101 |

n, total number of patients in the group overall. For BMI, n = 60 for the aseptic failure group, and n = 102 for the PJI group.

Metagenomics compared to synovial fluid culture.

IDSA diagnostic criteria for PJI and clinical evaluation of potentially infected TKA encompass multiple cultures and findings from preoperative and intraoperative sources. Synovial fluid was the only sample tested by metagenomics in this study; therefore, metagenomic results of species-level analysis were compared directly to results from synovial fluid culture. The performance of metagenomic sequencing compared to that of synovial fluid culture is indicated in Table 3, with new or missed species by metagenomic analysis listed in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

Performance of metagenomic sequencing compared to that of synovial fluid culture

| Sample type (n)a | No. of samples (%)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Identical finding | Organism not identified by metagenomics | New organism(s) detected by metagenomics | |

| Aseptic failure (61) | 56 (91.8) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (6.6) |

| Synovial fluid culture-positive PJI (82) | 67 (81.7) | 14 (17.1) | 3 (3.7) |

| Synovial fluid culture-negative PJI (25) | 21 (84.0) | NA | 4 (16.0) |

Included are samples for which identical or discrepant findings between synovial fluid culture and metagenomic sequencing were observed. n, number of samples in the group.

In two cases of culture-positive PJI, the pathogen identified by metagenomics did not match the pathogen identified by synovial fluid culture. These cases are included in the totals shown for both the organisms not identified and the new organisms. NA, not applicable.

TABLE 4.

Species from discordant samples

| Organism group | Name(s)a |

|---|---|

| PJI organism not detected by metagenomics | Staphylococcus epidermidis (9), Staphylococcus lugdunensis, Staphylococcus aureus, Serratia marcescens, Candida albicans, Cutibacterium acnes |

| Putative organism detected in aseptic failure case(s) | Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter junii, Acinetobacter johnsonii, Dolosigranulum pigrum |

| Putative additional organism detected in culture-positive PJI case(s) | Salpingoeca rosetta, Staphylococcus aureus, Afipia broomeae, Bradyrhizobium japonicum |

| Putative organism detected in culture-negative PJI case(s) | Salpingoeca rosetta (2), Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis,* Finegoldia magna,* Anaerococcus vaginalis |

Listed are new species detected or missed by metagenomics compared to results with synovial fluid culture. Values in parentheses indicate the number of different samples in which the noted difference was observed. Asterisks indicate an organism identified in cultures other than synovial fluid. F. magna and A. vaginalis were detected as a putative polymicrobial infection in one culture-negative PJI case.

Metagenomic analysis of aseptic failure.

Unrecognized or occult infection has been implicated in failure of prosthetic joints believed to be aseptic. To assess whether microorganisms missed by routine diagnostics were present in prosthetic joints that failed for reasons other than obvious infection, 61 synovial fluids from cases classified as aseptic failures were analyzed by metagenomics (Table 3). Of these, four (6.6%) exhibited sufficient reads and reference genome coverage to suggest the presence of microorganisms as determined by the thresholds applied. All were known to cause PJI (one Staphylococcus aureus, two Acinetobacter species, and one Dolosigranulum pigrum) although the non-S. aureus findings could also be contaminants (Table S1). In one of the four cases, the organism (Acinetobacter johnsonii) was detected by both analytic tools. Two (S. aureus and D. pigrum) were identified by LMAT alone, and one (Acinetobacter junii) was identified by MetaPhlan2 alone (Table S1). For one case of aseptic failure with growth from synovial fluid culture (sample 646), metagenomics showed insignificant findings using both analytic tools, suggesting possible culture contamination (Table S1). A large number of microbial reads and species identifications (by LMAT) were found in many aseptic failure cases. These identifications were primarily from contaminant genera identified in negative controls. These findings suggest a negative correlation between input amount of total DNA and detection of contaminating DNA.

Metagenomic analysis of prosthetic joint infection.

To evaluate shotgun metagenomics as a tool to identify prosthetic joint pathogens in synovial fluid compared to the use of synovial fluid culture, 107 synovial fluid specimens from patients with PJI, classified by IDSA definitions or clinical review, were examined. Of these, 82 were culture positive, and 25 were culture negative. For the culture-positive cases, the pathogen(s) identified by culture was also detected by metagenomics in 68 (82.9%) cases (Table S1). Metagenomics provided identical findings to those of culture in 67 (81.7%) cases, with additional pathogens, not detected by culture, detected in 3 (3.7%) cases (Table 3). Of these, one case (sample 815), the single polymicrobial infection that was identified by culture, had the same organisms and two more detected by metagenomics. One of these species (Afipia broomeae) was identified by both metagenomic analytic tools, MetaPhlan2 and LMAT. The second species (Bradyrhizobium japonicum) was detected by LMAT alone (Table S1). For the remaining two cases (samples 515 and 785), the pathogen detected by metagenomics was different from that detected by conventional culture, and in one of these samples (sample 515) the species (S. aureus) was identified by both metagenomic analytic tools (Table 3).

In 14 of the culture-positive PJI cases, the pathogen identified by culture was not identified using metagenomics (Table 3). For three cases (samples 137, 382, and 727), the pathogen identified by culture was identified by metagenomic analysis, exhibiting sufficient reads and genome coverage across the reference genome, but was excluded because of failure to meet the percentage cutoff for species-specific reads as a proportion of all bacterial reads present. For two cases (samples 8 and 819), the pathogen identified by culture was identified by metagenomic analysis, exhibiting sufficient reads and percentage of species-specific reads as a proportion of all bacterial reads, but was excluded because of failure to meet the percentage cutoff for genome coverage across a reference genome. In nine of these missed cases (69.2%), the undetected pathogen was a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, and in six cases, the subjects had received antibiotics within 4 weeks of synovial fluid aspiration (Table S1).

Analysis of the 25 culture-negative synovial fluid cases yielded potential pathogens by metagenomic analysis in 4 (16.0%) cases (Table 3). Of these new identifications, two species (Finegoldia magna and Enterococcus faecalis) were found by culture in specimen types other than synovial fluid (Table S1). Genus-level analysis of the culture-negative PJIs yielded a potential identification (Staphylococcus species) (sample 198) that was later confirmed by culture (Staphylococcus epidermidis) in specimen types other than synovial fluid acquired intraoperatively. This identification did not, however, meet thresholds for species-level identification.

DISCUSSION

Accurate diagnosis and identification of pathogens involved in PJI are crucial to guide surgical management and antibiotic therapy. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing has the potential to transform how these infections are diagnosed. Here, we evaluated the use of metagenomic shotgun sequencing applied to synovial fluids collected from the site of 168 total knee arthroplasties. We developed a novel filtering strategy to attempt to ensure that contaminating and background DNA was ignored while true infections were detected, and we utilized different taxonomic assignment algorithms to deliver high sensitivity and specificity for taxonomic classification of reads. We found that metagenomics can detect most pathogens identified by synovial fluid culture (82.9% at the species level and 90.2% at the genus level), as well as some that are not identified by culture. For genus- and species-level analyses of the 25 culture-negative PJIs, where routine microbiology was uninformative, potential pathogens were identified by metagenomic analysis in 6 (24%) and 4 (16%) patients, respectively. Three of these potential pathogens identified by metagenomic analysis, including genus- and species-level analyses, were later confirmed by culture of intraoperative specimens, including one (sample 578) which was from a patient who was on chronic suppressive antimicrobial therapy. Notably, in 18 culture-positive PJI cases, the known pathogen(s), based on synovial fluid culture, was detected by only one of the taxonomic assignment tools. Of the three potential pathogens subsequently identified by culture of specimen sources other than synovial fluid, two were detected by only one of the taxonomic assignment tools. These discrepancies highlight the utility of using multiple analytic tools to overcome deficiencies of individual methods.

Sequencing failed to detect the pathogen identified by synovial fluid culture in 14 of the 82 culture-positive PJIs. For five of the missed identifications, the known pathogen was present in the metagenomic analysis but was excluded for failure to meet one of three criteria. The results of analysis using lower thresholds would yield higher sensitivity in this regard, but specificity would be impacted by contaminating DNA. The level of confidence at which these results can be made and the amount of genetic information recovered by lowering thresholds would also be compromised.

To test the hypothesis that a microorganism(s) contributes to failure of prosthetic joints believed to be aseptic, 61 synovial fluid samples aspirated at the site of TKA failure for reasons other than infection were examined. Results from metagenomic analysis yielded potential pathogens in just four cases. While these results and insignificant findings for culture-negative PJIs (21/25) do not rule out a potential role of microorganisms in these cases and in TKA failure, we were unable to find evidence supporting the presence of pathogens at or above the thresholds applied.

Various definitions have been proposed as diagnostic criteria of PJI. To assess whether the criteria used impact the results, we reclassified this cohort using criteria from the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (39). This resulted in one reclassified case (sample 383), with 106 PJI classifications (81 culture positive and 25 culture negative) and 62 aseptic failure classifications. Of the 106 PJIs, 11 did not meet MSIS PJI diagnostic criteria but were classified PJI by clinical review. Ten of these cases were common to the 11 clinical review PJI classifications that did not meet IDSA criteria. The variable case, considered culture-positive PJI using IDSA criteria, showed insignificant findings on metagenomic analysis and was regarded as a missed identification for Cutibacterium acnes. Using MSIS criteria, this case would have been considered aseptic failure with positive growth on synovial fluid culture. It is possible, using this classification, that insignificant findings by metagenomic analysis indicate potential synovial fluid culture contamination.

We recognize many limitations of this study. An important limitation for all studies investigating PJI is the lack of a perfect gold standard for diagnosis. Accurate diagnosis and discrimination of aseptic from septic failure are therefore difficult. Additionally, metagenomic analysis of clinical specimens for infectious disease diagnostics is limited by the overwhelming presence of host DNA. Effective microbial enrichment and DNA isolation are therefore crucial to minimize the amount of host DNA sequenced while isolating as much pathogenic (microbial) DNA as possible. Microbial enrichment through host cell lysis and DNA degradation using the MolYsis basic kit was applied in this study. It is important to note that the MolYsis basic kit is designed for the pretreatment of whole blood and not specifically for specimen types such as the type used in this study. Multiple studies have reported a wide range of pathogens detectable by PCR following MolYsis treatment, but quantitative studies are needed to assess potential microbial DNA degradation of certain species (40). Alternative microbial DNA enrichment methods are available but have the potential to introduce other biases. It is also possible to omit microbial enrichment and sequence at higher depths, but this would greatly increase the cost per sample.

A major challenge in the field of metagenomics, seen in this study and others, is the critical impact that DNA from extraneous sources has on results obtained from clinical samples, especially those containing low biomass (i.e., synovial fluid) (29). Metagenomic analysis of every sample, including cases believed to be aseptic and negative controls, yielded read identifications (by LMAT) for microorganisms other than known or suspected pathogens. Analysis is further complicated by the common contaminants (e.g., Acinetobacter, Streptococcus, or Cutibacterium species) also being among the common causes of PJIs, making clinical relevance difficult to discern based on identification alone. Clinical applications of metagenomic sequencing have used a wide range of pathogen read numbers to make diagnoses, highlighting the challenge of defining cutoffs for the presence or absence of microorganisms. Combining the analysis of negative controls to determine the nucleic acid background of the reagents used for sequencing, using multiple algorithms for taxonomic assignment of reads, and establishing thresholds to filter low-level contaminating DNA appear to aid in the differentiation of real versus background reads. Potential identifications for Salpingoeca rosetta, however, suggest false positives may still be affecting results. The unusual identifications of this species surpassed thresholds applied; upon further analysis, reads were determined to be of low complexity. Human reads were removed from our analysis, but it is possible that insufficient removal of human DNA prior to sequencing and large amounts of noncoding and repetitive elements common to eukaryotes and fungi play a key role in false positive identifications. Validation of these methods is needed, however, to assess potential biases that may discriminate against pathogens of interest. Technically, our data could be used for antimicrobial resistance prediction, but this was not carried out in our study.

Ruppé et al. published a study utilizing metagenomics to examine bone and joint infections of various specimen types (26). Of 104 samples, only 24 (from 14 individuals) contained sufficient microbial DNA concentrations to qualify for metagenomic sequencing by the authors' criteria. The limited diversity of clinical situations this study was able to address as a result of low microbial DNA concentrations is a limitation. Utilizing microbial enrichment methods to overcome this, we analyzed all of our samples, presenting a data set more representative of what would likely to be encountered in clinical settings. Results from the study by Ruppé et al. identified known pathogens in all eight monomicrobial specimens, and the sensitivities to detect organisms present in polymicrobial cases at the genus and species level were 74.5% and 58.2%, respectively. Across the majority of samples, Ruppé et al. also observed a number of detections of bacteria not found in culture. Given the origin of some of the samples tested (i.e., mandibular), discrepant identifications may be real or a result of contamination with normal flora or otherwise. Metagenomic sequencing of negative controls and common contaminants identified, however, suggest similar issues with reagent and extraneous DNA contamination to those encountered in previous studies (25, 41–43).

A recent study published by Tarabichi et al. assessed the potential of targeted metagenomic 16S rRNA gene sequencing applied to synovial fluids for the diagnosis of PJI (27). Synovial fluids acquired from the site of primary and revised total knee and hip arthroplasties were examined. Results demonstrated 88.2% (15/17) concordance (by the author's definition) between sequencing and culture-positive PJI and identified organisms in 9 (81.8%) of the 11 culture-negative PJIs tested. Of the 36 culture-negative aseptic revisions and 17 primary arthroplasties analyzed, sequencing identified microbes in 9 (25.0%) and 6 (35.3%) cases, respectively. The approach used in this study focused on the 16S rRNA gene target, as opposed to whole-genome sequencing, limiting the amount of gene content information recovered, which is a key advantage of shotgun metagenomic sequencing over targeted 16S rRNA gene sequencing. For the results reported, the proposed definitions of concordance between sequencing and culture do not account for additional microbes identified by sequencing that were not found in culture, and while this study acknowledges the issue of background and contaminating reads, it is not addressed in the methods. The pattern of the microbes identified in cases of aseptic revision and primary arthroplasty (C. acnes and organisms originating from the Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria phyla) suggests issues with contamination (25, 29). Additionally, the calculated sensitivity (89.3%) and specificity (73.0%) for detection of any bacteria by sequencing assumed any detected bacterium to be pathogenic.

The high cost of next-generation sequencing and the materials used in our study, calculated at several hundred U.S. dollars per sample, compared to the supply cost of standard culture, which is a few dollars, and computational demand are obstacles to this approach. Metagenomics as it currently stands is not economically justifiable for application in every case. Additionally, important limitations of computational analysis are the size and completeness of reference genome databases. The tools utilized in this study for taxonomic assignment of reads and identification of potential pathogens rely on reference databases of previously sequenced organisms. This confines detection and identification to species previously identified and annotated. As a result, false negatives or incorrect identifications may occur due to incomplete or missing taxonomic representation in databases.

This study demonstrates that metagenomic shotgun sequencing can detect pathogens involved in PJI when applied to synovial fluid. Improvements to the methods and bioinformatics analyses are ongoing for microbial enrichment and detection, identification of contamination, and full antimicrobial susceptibility reporting. As sequencing technology evolves, it could theoretically offer complete microbiologic diagnosis without the need for culture. Metagenomic sequencing is a new tool for diagnosis of PJI. Currently, though, our data support the role of metagenomics only when standard-of-care testing is uninformative.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health (R01 AR056647). R.P. is also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (R01 AI091594, R21 AI125870). M.I.I. is also supported by the National Institutes of Health (R25 GM075148).

R.P. reports grants from CD Diagnostics, BioFire, Curetis, Merck, Hutchison Biofilm Medical Solutions, Accelerate Diagnostics, Allergan, and The Medicines Company. R.P. is or has been a consultant to Curetis, Qvella, St. Jude, Beckman Coulter, Morgan Stanley, Heraeus Medical GmbH, CorMatrix, Specific Technologies, Diaxonit, Selux Dx, GenMark Diagnostics, LBT Innovations Ltd., PathoQuest, and Genentech; monies are paid to Mayo Clinic. In addition, R.P. has a patent on a Bordetella pertussis/B. parapertussis PCR assay issued, a patent on a device/method for sonication, with royalties paid by Samsung to Mayo Clinic, and a patent on an antibiofilm substance issued. R.P. has served on an Actelion data monitoring board. R.P. receives travel reimbursement from ASM and IDSA, an editor's stipend from ASM and IDSA, and honoraria from the NBME, Up-to-Date, and the Infectious Diseases Board Review Course.

Footnotes

For a commentary on this article, see https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00850-18.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00402-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corvec S, Portillo ME, Pasticci BM, Borens O, Trampuz A. 2012. Epidemiology and new developments in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Int J Artif Organs 35:923–934. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran E, Byren I, Atkins BL. 2010. The diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 65(Suppl 3):iii45–iii54. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tande AJ, Patel R. 2014. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:302–345. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00111-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson WR, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 56:e1–e25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson MR, Naccache SN, Samayoa E, Biagtan M, Bashir H, Yu G, Salamat SM, Somasekar S, Federman S, Miller S, Sokolic R, Garabedian E, Candotti F, Buckley RH, Reed KD, Meyer TL, Seroogy CM, Galloway R, Henderson SL, Gern JE, DeRisi JL, Chiu CY. 2014. Actionable diagnosis of neuroleptospirosis by next-generation sequencing. N Engl J Med 370:2408–2417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naccache SN, Peggs KS, Mattes FM, Phadke R, Garson JA, Grant P, Samayoa E, Federman S, Miller S, Lunn MP, Gant V, Chiu CY. 2015. Diagnosis of neuroinvasive astrovirus infection in an immunocompromised adult with encephalitis by unbiased next-generation sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 60:919–923. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann B, Tappe D, Hoper D, Herden C, Boldt A, Mawrin C, Niederstrasser O, Muller T, Jenckel M, van der Grinten E, Lutter C, Abendroth B, Teifke JP, Cadar D, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Ulrich RG, Beer M. 2015. A variegated squirrel bornavirus associated with fatal human encephalitis. N Engl J Med 373:154–162. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mongkolrattanothai K, Naccache SN, Bender JM, Samayoa E, Pham E, Yu G, Dien Bard J, Miller S, Aldrovandi G, Chiu CY. 2017. Neurobrucellosis: unexpected answer from metagenomic next-generation sequencing. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 6:393–398. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greninger AL, Messacar K, Dunnebacke T, Naccache SN, Federman S, Bouquet J, Mirsky D, Nomura Y, Yagi S, Glaser C, Vollmer M, Press CA, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Dominguez SR, Chiu CY. 2015. Clinical metagenomic identification of Balamuthia mandrillaris encephalitis and assembly of the draft genome: the continuing case for reference genome sequencing. Genome Med 7:113. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salzberg SL, Breitwieser FP, Kumar A, Hao H, Burger P, Rodriguez FJ, Lim M, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Gallia GL, Tornheim JA, Melia MT, Sears CL, Pardo CA. 2016. Next-generation sequencing in neuropathologic diagnosis of infections of the nervous system. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 3:e251. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson MR, Suan D, Duggins A, Schubert RD, Khan LM, Sample HA, Zorn KC, Rodrigues Hoffman A, Blick A, Shingde M, DeRisi JL. 2017. A novel cause of chronic viral meningoencephalitis: Cache valley virus. Ann Neurol 82:105–114. doi: 10.1002/ana.24982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mai NTH, Phu NH, Nhu LNT, Hong NTT, Hanh NHH, Nguyet LA, Phuong TM, McBride A, Ha DQ, Nghia HDT, Chau NVV, Thwaites G, Tan LV. 2017. Central nervous system infection diagnosis by next-generation sequencing: a glimpse into the future? Open Forum Infect Dis 4:ofx046. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murkey JA, Chew KW, Carlson M, Shannon CL, Sirohi D, Sample HA, Wilson MR, Vespa P, Humphries RM, Miller S, Klausner JD, Chiu CY. 2017. Hepatitis E virus-associated meningoencephalitis in a lung transplant recipient diagnosed by clinical metagenomic sequencing. Open Forum Infect Dis 4:ofx121. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu CY, Coffey LL, Murkey J, Symmes K, Sample HA, Wilson MR, Naccache SN, Arevalo S, Somasekar S, Federman S, Stryke D, Vespa P, Schiller G, Messenger S, Humphries R, Miller S, Klausner JD. 2017. Diagnosis of fatal human case of St. Louis Encephalitis Virus infection by metagenomic sequencing, California, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 23:1964–1968. doi: 10.3201/eid2310.161986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langelier C, Zinter MS, Kalantar K, Yanik GA, Christenson S, O'Donovan B, White C, Wilson M, Sapru A, Dvorak CC, Miller S, Chiu CY, DeRisi JL. 2018. Metagenomic sequencing detects respiratory pathogens in hematopoietic cellular transplant patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197:524–528. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1097LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pendleton KM, Erb-Downward JR, Bao Y, Branton WR, Falkowski NR, Newton DW, Huffnagle GB, Dickson RP. 2017. Rapid pathogen identification in bacterial pneumonia using real-time metagenomics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196:1610–1612. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0537LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graf EH, Simmon KE, Tardif KD, Hymas W, Flygare S, Eilbeck K, Yandell M, Schlaberg R. 2016. Unbiased detection of respiratory viruses by use of RNA sequencing-based metagenomics: a systematic comparison to a commercial PCR panel. J Clin Microbiol 54:1000–1007. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03060-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doan T, Wilson MR, Crawford ED, Chow ED, Khan LM, Knopp KA, O'Donovan BD, Xia D, Hacker JK, Stewart JM, Gonzales JA, Acharya NR, DeRisi JL. 2016. Illuminating uveitis: metagenomic deep sequencing identifies common and rare pathogens. Genome Med 8:90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sardi SI, Somasekar S, Naccache SN, Bandeira AC, Tauro LB, Campos GS, Chiu CY. 2016. Coinfections of Zika and chikungunya viruses in Bahia, Brazil, identified by metagenomic next-generation sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 54:2348–2353. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00877-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukui Y, Aoki K, Okuma S, Sato T, Ishii Y, Tateda K. 2015. Metagenomic analysis for 482detecting pathogens in culture-negative infective endocarditis. J Infect Chemother 21:882–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grard G, Fair JN, Lee D, Slikas E, Steffen I, Muyembe JJ, Sittler T, Veeraraghavan N, Ruby JG, Wang C, Makuwa M, Mulembakani P, Tesh RB, Mazet J, Rimoin AW, Taylor T, Schneider BS, Simmons G, Delwart E, Wolfe ND, Chiu CY, Leroy EM. 2012. A novel rhabdovirus associated with acute hemorrhagic fever in central Africa. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002924. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Federman S, Yu G, Mbala P, Bres V, Stryke D, Bouquet J, Somasekar S, Linnen JM, Dodd R, Mulembakani P, Schneider BS, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Stramer SL, Chiu CY. 2015. Rapid metagenomic identification of viral pathogens in clinical samples by real-time nanopore sequencing analysis. Genome Med 7:99. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0220-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kujiraoka M, Kuroda M, Asai K, Sekizuka T, Kato K, Watanabe M, Matsukiyo H, Saito T, Ishii T, Katada N, Saida Y, Kusachi S. 2017. Comprehensive diagnosis of bacterial infection associated with acute cholecystitis using metagenomic approach. Front Microbiol 8:685. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Wylie KM, El Feghaly RE, Mihindukulasuriya KA, Elward A, Haslam DB, Storch GA, Weinstock GM. 2016. Metagenomic approach for identification of the pathogens associated with diarrhea in stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol 54:368–375. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01965-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Street TL, Sanderson ND, Atkins BL, Brent AJ, Cole K, Foster D, McNally MA, Oakley S, Peto L, Taylor A, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Eyre DW. 2017. Molecular diagnosis of orthopedic-device-related infection directly from sonication fluid by metagenomic sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 55:2334–2347. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00462-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruppe E, Lazarevic V, Girard M, Mouton W, Ferry T, Laurent F, Schrenzel J. 2017. Clinical metagenomics of bone and joint infections: a proof of concept study. Sci Rep 7:7718. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarabichi M, Shohat N, Goswami K, Alvand A, Silibovsky R, Belden K, Parvizi J. 2018. Diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: the potential of next-generation sequencing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 100:147–154. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thoendel M, Jeraldo P, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Chia N, Abdel MP, Steckelberg JM, Osmon DR, Patel R. 2017. A novel prosthetic joint infection pathogen, Mycoplasma salivarium, identified by metagenomic shotgun sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 65:332–335. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salter SJ, Cox MJ, Turek EM, Calus ST, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF, Turner P, Parkhill J, Loman NJ, Walker AW. 2014. Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol 12:87. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0087-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naccache SN, Greninger AL, Lee D, Coffey LL, Phan T, Rein-Weston A, Aronsohn A, Hackett J Jr, Delwart EL, Chiu CY. 2013. The perils of pathogen discovery: origin of a novel parvovirus-like hybrid genome traced to nucleic acid extraction spin columns. J Virol 87:11966–11977. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02323-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurence M, Hatzis C, Brash DE. 2014. Common contaminants in next-generation sequencing that hinder discovery of low-abundance microbes. PLoS One 9:e97876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strong MJ, Xu G, Morici L, Splinter Bon-Durant S, Baddoo M, Lin Z, Fewell C, Taylor CM, Flemington EK. 2014. Microbial contamination in next generation sequencing: implications for sequence-based analysis of clinical samples. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004437. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoendel M, Jeraldo P, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Yao J, Chia N, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP, Patel R. 10 April 2018. Identification of prosthetic joint infection pathogens using a shotgun metagenomics approach. Clin Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu J, Sadeghi S, Raymond A, Jackman SD, Nip KM, Mar R, Mohamadi H, Butterfield YS, Robertson AG, Birol I. 2014. BioBloom Tools: fast, accurate and memory-efficient host species sequence screening using bloom filters. Bioinformatics 30:3402–3404. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ames SK, Hysom DA, Gardner SN, Lloyd GS, Gokhale MB, Allen JE. 2013. Scalable metagenomic taxonomy classification using a reference genome database. Bioinformatics 29:2253–2260. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truong DT, Franzosa EA, Tickle TL, Scholz M, Weingart G, Pasolli E, Tett A, Huttenhower C, Segata N. 2015. Metaphlan2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat Methods 12:902–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Durbin R. 2010. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parvizi J. 2011. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 40:614–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gebert S, Siegel D, Wellinghausen N. 2008. Rapid detection of pathogens in blood culture bottles by real-time PCR in conjunction with the pre-analytic tool MolYsis. J Infect 57:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simner PJ, Miller S, Carroll KC. 2018. Understanding the promises and hurdles of metagenomic next-generation sequencing as a diagnostic tool for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 66:778–788. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thoendel M, Jeraldo P, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Yao J, Chia N, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP, Patel R. 2017. Impact of contaminating DNA in whole-genome amplification kits used for metagenomic shotgun sequencing for infection diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol 55:1789–1801. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02402-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thoendel M, Jeraldo PR, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Yao JZ, Chia N, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP, Patel R. 2016. Comparison of microbial DNA enrichment tools for metagenomic whole-genome sequencing. J Microbiol Methods 127:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanner MA, Goebel BM, Dojka MA, Pace NR. 1998. Specific ribosomal DNA sequences from diverse environmental settings correlate with experimental contaminants. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:3110–3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barton HA, Taylor NM, Lubbers BR, Pemberton AC. 2006. DNA extraction from low-biomass carbonate rock: an improved method with reduced contamination and the low-biomass contaminant database. J Microbiol Methods 66:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grahn N, Olofsson M, Ellnebo-Svedlund K, Monstein HJ, Jonasson J. 2003. Identification of mixed bacterial DNA contamination in broad-range PCR amplification of 16S rDNA V1 and V3 variable regions by pyrosequencing of cloned amplicons. FEMS Microbiol Lett 219:87–91. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)01190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.