The dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) is a major threat to public health. Rapid and accurate detection of CPE is essential for initiating appropriate antimicrobial treatment and establishing infection control measures.

KEYWORDS: carbapenemase, EDTA, Enterobacteriaceae, NDM, OXA-48, carbapenemase inactivation method, mCIM, phenotypic characterization, phenotypic detection, phenylboronic acid

ABSTRACT

The dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) is a major threat to public health. Rapid and accurate detection of CPE is essential for initiating appropriate antimicrobial treatment and establishing infection control measures. The carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), which has good sensitivity and specificity but a detection time of 20 h, was recently described. In this study, we evaluated the performances of a new version, the CIMplus test, which allows detection of carbapenemases in 8 h and characterization of carbapenemase classes, according to the Ambler classification, in 20 h. A panel of 110 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains, including 92 CPE strains (with NDM, VIM, IMP, KPC, GES, OXA-48, and OXA-48-like enzymes), was used to evaluate test performance. Carbapenemase activity was detected at 8 h and 20 h. Characterization of carbapenemase classes, using specific inhibitors, was possible in 20 h. The CIMplus test had sensitivities of 95.7% and 97.8% at 8 h and 20 h, respectively, and a specificity of 94.4%, independent of the culture duration. Using a decision algorithm, this test was successful in identifying the carbapenemase class for 98.9% of tested CPE isolates (87/88 isolates). In total, the characterization was correct for 100%, 96.9%, and 100% of Ambler class A, B, and D isolates, respectively. Therefore, this test allows detection of carbapenemase activity in 8 h and characterization of carbapenemase classes, according to the Ambler classification, in 20 h. The CIMplus test represents a simple, affordable, easy-to-read, and accurate tool that can be used without any specific equipment.

INTRODUCTION

The worldwide emergence and spread of carbapenemase producers represent a clinical challenge and a public health threat (1). Carbapenemase enzymes are clustered in different classes that define their hydrolytic profiles; VIM, NDM, and IMP belong to the Ambler class B metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) and GES belong to class A, and OXA-48 and OXA-48-like belong to class D (2). These profiles are associated with resistance to carbapenems and to most β-lactam antibiotics (except for aztreonam for class B and third-generation cephalosporins for class D).

The mechanisms of carbapenem resistance are the production of carbapenemase, the association with extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), and/or the production of an AmpC β-lactamase combined with decreased membrane permeability. It is important to differentiate between these different resistance mechanisms to implement infection control measures (3).

To detect carbapenemase production, phenotype-based assays have been developed, including growth-based assays (4–6), biochemical tests (7), immunochromatogenic assays (8), and carbapenem hydrolysis assays using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (9). Some authors suggest that these tests may have low sensitivity to detect OXA-48-producing strains, however, and only a few methods are able to classify these enzymes according to the Ambler classification (4, 8, 10). Although molecular methods remain the gold standard, they are costly, limited by the targets used specifically in the test, and not accessible to all microbiology laboratories throughout the world (11).

Recently, a simple detection test, the carbapenem inactivation method (CIM) test, has been described; it has shown excellent performance in many centers, similar to the performance of commercial tests but with a lower cost (6, 12–15). A modified version of this test (mCIM) appears in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations for the detection of carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae (16, 17). Recently, the CLSI approved a modification of the mCIM, called the eCIM, that uses EDTA inhibition to detect class B carbapenemases (18). Lastly, the SMA-mCIM, a variant of the mCIM test, uses sodium mercaptoacetate (SMA) as an inhibitor to detect MBL enzymes (19).

The CIM test and its variants enable the detection of carbapenemases with optimal performance within 18 to 24 h. This lengthy delay affects the implementation of infection control measures and, in some cases, the prescription of appropriate antibiotic therapy for patients. Detection in 8 h was suggested by Van der Zwaluw et al., but the delay required for the reading and interpretation of the test results remains debated (6, 12, 14).

In this study, we describe a CIMplus version of the CIM test. With our test, carbapenemase activity can be detected within 8 h, including 2 h of incubation and 6 h of culture. Furthermore, we can identify the type of carbapenemase, according to the Ambler classification, in 20 h. The performance of our test is equivalent to that of the original test, which uses overnight cultures. Thus, the CIMplus test represents a valuable tool for guiding antibiotic therapy, epidemiological studies, and infection control procedures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates tested.

To evaluate the performance of the CIMplus test, we analyzed 110 Enterobacteriaceae strains with decreased susceptibility (intermediate or resistant) to at least one carbapenem (ertapenem, imipenem, or meropenem). This characteristic was defined by measuring the inhibition zone diameter or by determining the MICs of the carbapenems, with interpretation according to EUCAST recommendations (20). This strain collection was composed of 92 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) isolates (47 Klebsiella sp. isolates, 26 Escherichia coli isolates, 6 Enterobacter sp. isolates, 6 Citrobacter sp. isolates, and 7 Proteus sp. isolates) and 18 non-carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (non-CPE) isolates (9 K. pneumoniae isolates, 3 E. coli isolates, 4 Enterobacter sp. isolates, and 2 Citrobacter freundii isolates) from five French Hospitals and was partially described in previous studies (4, 21–23). The collection included isolates carrying the following carbapenemase genes: 17 isolates carrying blaKPC, 1 isolate carrying blaGES, 25 isolates carrying blaNDM, 8 isolates carrying blaVIM, 1 isolate carrying blaIMP, 32 isolates carrying blaOXA-48, 5 isolates carrying blaOXA-181, 1 isolate carrying blaOXA-244, and 2 isolates carrying both blaNDM and blaOXA-181. Table S1 in the supplemental material provides specific information for each isolate, including the carbapenem resistance mechanisms, the carbapenem MICs, and the β-lactamase genes. The carbapenem MICs (imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem) were determined by using the Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and were interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines (20).

CIMplus testing.

Isolates were subcultured from frozen stock to tryptic soy agar (TSA). The protocol used in our study to detect the presence of carbapenemases was similar to the standard CIM protocol (6). Briefly, a 10-μg meropenem disk (Bio-Rad, Marne La Coquette, France) was added to 400 μl of distilled water containing a 10-μl loopful of the tested strain, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h at 35°C. Simultaneously, a Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plate was streaked with the susceptible E. coli ATCC 25922 reference strain from a 0.5 McFarland standard inoculum and incubated at 35°C. This early incubation allowed the start of E. coli growth.

At the same time, to characterize the type of carbapenemase, 2 other suspensions were prepared, using the same protocol as for carbapenemase detection, to which were added inhibitors, i.e., either 0.05 M EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or 20 mg/ml phenylboronic acid (PBA) (Sigma-Aldrich). PBA was first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted in sterile water, with a final concentration of DMSO of 3.5%. After 2 h, the three meropenem disks were removed from the bacterial suspensions (with water, EDTA, or PBA) and placed on preincubated MHA plates, which were then reincubated at 35°C. Inhibition zones were evaluated 6 h (for the detection test) and 18 h (for the detection and characterization tests) after placement of the disks.

We considered that, if the tested isolate produced a carbapenemase, then the susceptible strain would grow to contact the disk. In contrast, if the tested isolate had decreased susceptibility to carbapenems without carbapenemase activity, then meropenem would be incompletely hydrolyzed and would retain activity. Similarly, in the characterization test, if the carbapenemase activity were inhibited by one of the inhibitors, then meropenem would retain activity and an inhibition zone around the disk would be observed. An inhibition zone corresponds to a visible diameter around the disk (>6 mm). When a carbapenemase is produced, the susceptible strain grows to contact the disk and therefore no diameter is visible.

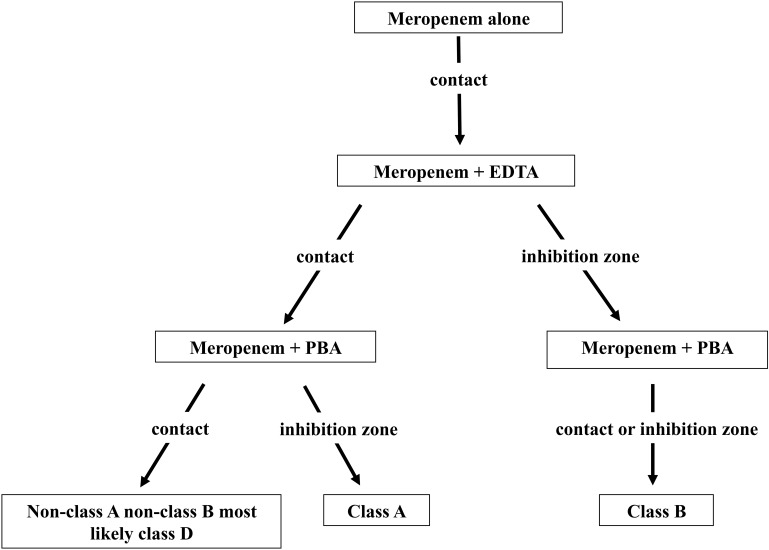

In cases with positive carbapenemase detection, the characterization of the carbapenemase class was interpreted as follows. (i) If the susceptible E. coli strain grows to contact the EDTA-incubated disk and the PBA-incubated disk, then the tested isolate is neither a class A nor a class B carbapenemase producer and thus is very likely to be a class D carbapenemase producer. (ii) If the susceptible E. coli strain grows with an inhibition zone around the EDTA-incubated disk and grows to contact the PBA-incubated disk, then the tested isolate is a class B carbapenemase producer. (iii) If the susceptible E. coli strain grows to contact the EDTA-incubated disk and grows with an inhibition zone around the PBA-incubated disk, then the tested isolate is a class A carbapenemase producer. (iv) If the susceptible E. coli strain grows with inhibition zones around the EDTA- and PBA-impregnated disks, then the tested isolate is considered to be a class B carbapenemase producer. Some class B carbapenemase-producing strains (17/34 strains) were also inhibited by PBA; those strains are presented in Table S1. The decision algorithm is presented in Fig. 1. All of the tests were performed in the same clinical microbiology laboratory at Robert Debré Hospital.

FIG 1.

Strategy to identify the type of carbapenemase by using meropenem disks (10 μg) with or without a specific carbapenemase inhibitor (PBA for class A enzymes and EDTA for class B enzymes).

RESULTS

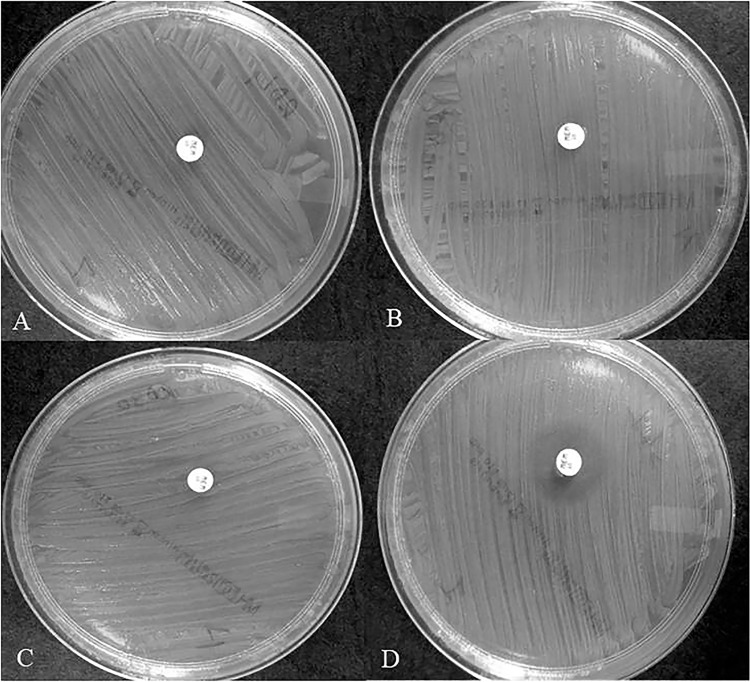

The CIMplus test was evaluated with 110 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates, to detect carbapenemase activity at 8 h and 20 h and to characterize the carbapenemase type in 20 h. Eighty-eight (95.7%) of the 92 CPE isolates were CMIplus positive at 8 h, and 90 (97.8%) of 92 were positive at 20 h (Table 1). All carbapenemase nonproducers (n = 18) except 1 isolate were CIMplus negative at 8 h and 20 h, as expected. The false-positive non-CPE isolate was a K. pneumoniae strain containing CTX-M-15, SHV-11, and TEM-1 β-lactamases, which are associated with possibly decreased membrane permeability. Based on these results, the detection performance of the CIMplus test had sensitivities of 95.7% and 97.8% at 8 h and 20 h, respectively, and a specificity of 94.4%, independent of the culture duration (Table 1). All of the class A and D isolates were well detected by the CIMplus test at 8 h and 20 h. The CIMplus test failed to detect 4 of 34 class B CPE isolates at 8 h (2 strains with VIM enzymes and 2 with NDM enzymes), and 2 of 34 isolates remained negative at 20 h (2 hypermucoid VIM-producing K. pneumoniae strains). Phenotypic and genotypic methods were repeated to confirm the presence of carbapenemase enzymes in the 2 latter isolates. All CIMplus-positive isolates grew to contact the disks, whereas negative isolates had median inhibition zone diameters of 18 mm (range, 16 to 20 mm) and 21 mm (range, 20 to 25 mm) at 8 h (Fig. 2) and 20 h, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Performance of the CIMplus test in detecting carbapenemase activity and identifying the carbapenemase class of CPE isolates

| Time of detection and bacteria tested | Detection of carbapenemase activity (n = 110) |

Characterization of carbapenemase type (n = 88)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. positive | No. negative | Total no. | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | No. well characterizedb | No. mischaracterizedb | Total no. | Categorical agreement (%) | |

| 8 h | |||||||||

| Class A CPE | 18 | 0 | 18 | 100 | |||||

| Class B CPE | 30 | 4 | 34 | 88.2 | |||||

| Class D CPE | 38 | 0 | 38 | 100 | |||||

| Class B and D CPE | 2 | 0 | 2 | 100 | |||||

| Any class of CPE | 88 | 4 | 92 | 95.7 | |||||

| Non-CPE | 1 | 17 | 18 | ||||||

| All isolates | 89 | 21 | 110 | 95.7 | 94.4 | ||||

| 20 h | |||||||||

| Class A CPE | 18 | 0 | 18 | 100 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 100 | |

| Class B CPE | 32 | 2 | 34 | 94.1 | 31 | 1 | 32 | 96.9 | |

| Class D CPE | 38 | 0 | 38 | 100 | 38 | 0 | 38 | 100 | |

| Class B and D CPE | 2 | 0 | 2 | 100 | |||||

| Any class of CPE | 90 | 2 | 92 | 97.8 | 87 | 1 | 88 | 98.9 | |

| Non-CPE | 1 | 17 | 18 | ||||||

| All isolates | 91 | 19 | 110 | 97.8 | 94.4 | ||||

All CPE isolates that tested positive with the CIMplus test in 18 h except for the 2 isolates that coproduced 2 carbapenemases.

The algorithm described in Fig. 1 was used for categorization.

FIG 2.

Examples of results for different carbapenemase classes identified with the CIMplus test at 8-h readings. (A) RD30 (KPC). (B) RD7 (NDM). (C) RD4 (OXA-48). (D) SL1 (absence of carbapenemase). The culture of E. coli ATCC 25922 grows to contact the meropenem disks with the CPE isolates (A, B, and C), whereas an inhibition zone diameter is detected with the carbapenemase nonproducer (D).

Characterization of the carbapenemase type was performed with 88 strains, equivalent to the CIMplus-positive isolates but excluding 2 strains with double carbapenemases. The interpretation of the carbapenemase type was made according to the decision algorithm presented in Fig. 1. Among those 88 strains, 98.9% (87/88 strains) were well characterized, with median inhibition zones of 17 mm and 22 mm for the PBA- and EDTA-impregnated disks, respectively. In total, characterization was correct for 100%, 96.9%, and 100% of class A, B, and D isolates, respectively (Table 1). The only misclassified isolate was an IMP-1-producing K. pneumoniae strain that was classified as class D instead of class B (Table S1). These results were confirmed in a second experiment with 2 different readers.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we present and evaluate the performance of the CIMplus test. We can conclude that it has high sensitivity in the detection of CPE, comparable to that of the original CIM test and the CLSI-approved mCIM test (6, 12, 16, 17). The CIMplus test can detect carbapenemase activity in isolates producing KPC, GES, NDM, VIM, IMP, OXA-48, and OXA-48-like enzymes.

The CIM test results are considered to be interpretable in 8 h, although some authors discuss this point (6, 12, 14). When the susceptible E. coli culture duration is increased with the preincubation step, then the performance of the CIMplus test at 8 h for carbapenemase detection is satisfactory. Reading and interpretation difficulties have not been reported, allowing complete detection within 1 work day (Fig. 2). Only 2 hypermucoid K. pneumoniae strains were not detected at 8 h or 20 h, as they were impossible to suspend in water; this phenomenon was reported previously (13). Also, 2 strains were not detected at 8 h but were detected at 20 h, probably due to partial hydrolysis of the meropenem disk causing a delay in the growth of the susceptible E. coli strain to contact the disk. The false-positive non-CPE strain was identified as a K. pneumoniae strain containing, among others, the blaCTX-M-15 gene. We hypothesize that this result is due to low carbapenemase activity of ESBL enzymes (CTX-M), as described previously (24).

As presented in the algorithm (Fig. 1), we observed satisfactory performance of the CIMplus test in identifying the type of carbapenemase within 20 h. Indeed, we obtained correct characterization for 98.9% of tested CPE isolates (87/88 isolates) and categorical agreements between 96.9% and 100%, depending on the enzyme class (Table 1). All of the carbapenemase types were well characterized except for 1 IMP-1-producing K. pneumoniae isolate, which was classified as class D instead of class B. To understand this difference, we conducted further experiments. When the EDTA concentration was increased 3-fold, an inhibition zone was observed (data not presented), confirming that this enzyme could be inhibited when a high concentration of EDTA was used. However, nonspecific inhibition was detected for non-class B carbapenemases at this higher concentration. Because IMP and GES carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains are scarce in France, we could test only 1 strain per type; therefore, our results should be confirmed with a larger number of strains.

The CIMplus test allows detection and characterization of the carbapenemase type, with a cost of €0.53 per tested isolate; this cost includes the meropenem disks, the MHA plates, the PBA, the DMSO, and the EDTA. The latter three reagents are stable at ambient temperature and therefore can be kept for several years. Moreover, this test is accessible to laboratories throughout the world, as it requires only basic laboratory materials.

The test we evaluated in this study has many advantages but also some limitations. Here carbapenemase detection was possible in 8 h, but some authors have described faster phenotypic tests (10, 21). The test also requires many bacteria; therefore, the initiation of our experiment required a rich culture. Moreover, characterization of the carbapenemase type was not possible for 2 E. coli strains that simultaneously produced 2 carbapenemases from different classes. Results for characterization of isolates that produce multiple carbapenemases depend on the classes of the enzymes they produce. This issue has been raised for other phenotype-based characterization tests (10). Finally, this test was evaluated with isolates from various geographical origins, but no typing method was used. Therefore, we cannot exclude genetic links between some isolates. Furthermore, we tested only the major carbapenemase types (NDM, VIM, IMP, KPC, GES, and OXA-48/OXA-48-like) and a limited number of carbapenemase nonproducers. The performance of the test should be evaluated using different carbapenemase enzymes and a larger number of non-CPE isolates. The last item could help increase the specificity of the CIMplus test, as demonstrated in previous studies (6, 12–15). In conclusion, the CIMplus test represents a simple, affordable, accessible, and accurate technique that requires only basic laboratory equipment. It allows the detection and characterization of carbapenemase classes among CPEs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financed with internal funds.

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00137-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantón R, Akóva M, Carmeli Y, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, Livermore DM, Miriagou V, Naas T, Rossolini GM, Samuelsen Ø, Seifert H, Woodford N, Nordmann P. 2012. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:413–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Queenan AM, Bush K. 2007. Carbapenemases: the versatile β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez F, El Chakhtoura NG, Papp-Wallace KM, Wilson BM, Bonomo RA. 2016. Treatment options for infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: can we apply “precision medicine” to antimicrobial chemotherapy? Expert Opin Pharmacother 17:761–781. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1145658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birgy A, Bidet P, Genel N, Doit C, Decré D, Arlet G, Bingen E. 2012. Phenotypic screening of carbapenemases and associated β-lactamases in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 50:1295–1302. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06131-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalhaes CG, Picão RC, Nicoletti AG, Xavier DE, Gales AC. 2010. Cloverleaf test (modified Hodge test) for detecting carbapenemase production in Klebsiella pneumoniae: be aware of false positive results. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:249–251. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Zwaluw K, de Haan A, Pluister GN, Bootsma HJ, de Neeling AJ, Schouls LM. 2015. The carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), a simple and low-cost alternative for the Carba NP test to assess phenotypic carbapenemase activity in Gram-negative rods. PLoS One 10:e0123690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp. J Clin Microbiol 50:3773–3776. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01597-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glupczynski Y, Evrard S, Ote I, Mertens P, Huang T-D, Leclipteux T, Bogaerts P. 2016. Evaluation of two new commercial immunochromatographic assays for the rapid detection of OXA-48 and KPC carbapenemases from cultured bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1217–1222. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papagiannitsis CC, Studentová V, Izdebski R, Oikonomou O, Pfeifer Y, Petinaki E, Hrabák J. 2015. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry meropenem hydrolysis assay with NH4HCO3, a reliable tool for direct detection of carbapenemase activity. J Clin Microbiol 53:1731–1735. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03094-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Rapid identification of carbapenemase types in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. by using a biochemical test. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6437–6440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01395-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hrabák J, Chudáčková E, Papagiannitsis CC. 2014. Detection of carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae: a challenge for diagnostic microbiological laboratories. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:839–853. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthier L, Bonnin RA, Dortet L, Naas T. 2017. Retrospective and prospective evaluation of the carbapenem inactivation method for the detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. PLoS One 12:e0170769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamada K, Kashiwa M, Arai K, Nagano N, Saito R. 2016. Comparison of the modified-Hodge test, Carba NP test, and carbapenem inactivation method as screening methods for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Microbiol Methods 128:48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguirre-Quiñonero A, Cano ME, Gamal D, Calvo J, Martínez-Martínez L. 2017. Evaluation of the carbapenem inactivation method (CIM) for detecting carbapenemase activity in enterobacteria. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 88:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akhi MT, Khalili Y, Ghotaslou R, Kafil HS, Yousefi S, Nagili B, Goli HR. 2017. Carbapenem inactivation: a very affordable and highly specific method for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates compared with other methods. J Chemother 29:144–149. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2016.1199506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierce VM, Simner PJ, Lonsway DR, Roe-Carpenter DE, Johnson JK, Brasso WB, Bobenchik AM, Lockett ZC, Charnot-Katsikas A, Ferraro MJ, Thomson RB, Jenkins SG, Limbago BM, Das S. 2017. Modified carbapenem inactivation method for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase production among Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 55:2321–2333. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00193-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2017. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 20th informational supplement. CLSI M100-S20 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing—28th ed CLSI M100 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada K, Kashiwa M, Arai K, Nagano N, Saito R. 2017. Evaluation of the modified carbapenem inactivation method and sodium mercaptoacetate-combination method for the detection of metallo-β-lactamase production by carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Microbiol Methods 132:112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2016. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, version 6.0. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_6.0_Breakpoint_table.pdf.

- 21.Compain F, Gallah S, Eckert C, Arlet G, Ramahefasolo A, Decré D, Lavollay M, Podglajen I. 2016. Assessment of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae with the rapid and easy-to-use chromogenic β Carba Test. J Clin Microbiol 54:3065–3068. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01912-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decré D, Favier C, Arlet G. 2010. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:490–505. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenover FC, Canton R, Kop J, Chan R, Ryan J, Weir F, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, LaBombardi V, Persing DH. 2013. Detection of colonization by carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli in patients by use of the Xpert MDRO assay. J Clin Microbiol 51:3780–3787. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01092-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupont H, Gaillot O, Goetgheluck A-S, Plassart C, Emond J-P, Lecuru M, Gaillard N, Derdouri S, Lemaire B, Girard de Courtilles M, Cattoir V, Mammeri H. 2016. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-nonsusceptible enterobacterial isolates collected during a prospective interregional survey in France and susceptibility to the novel ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:215–221. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01559-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.