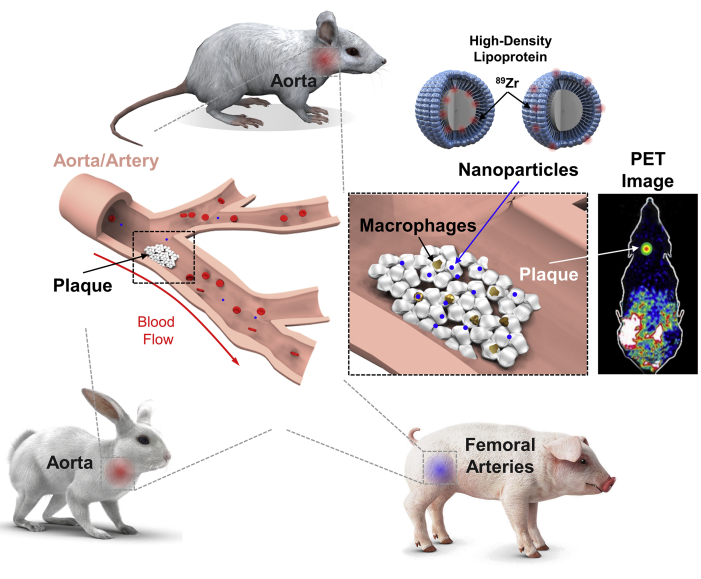

Central Illustration

Schematic of HDL Nanoparticles Used for PET Imaging

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) nanoparticles were synthesized containing the positron emission tomography (PET) isotope 89Zr and injected into atherosclerosis-bearing animals. Three animal models of atherosclerosis, mice, rabbits, and pigs, were tested. HDL nanoparticles entered plaque macrophages and monocytes, demonstrating delivery to atherosclerotic plaques in animal arteries as measured by PET molecular imaging.

Key Words: atherosclerosis, HDL, imaging, nanoparticles, macrophages/monocytes

Summary

Nanoparticles promise to advance the field of cardiovascular theranostics. However, their sustained and targeted delivery remains an important obstacle. The body synthesizes some “natural” nanoparticles, including high-density lipoprotein (HDL), which may home to the atherosclerotic plaque and promote cholesterol efflux. In a recent article published in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, investigators generated modified, radiolabeled HDL nanoparticles and confirmed they accumulated in atherosclerotic lesions from several different species. These approaches hold promise for the noninvasive diagnosis of vulnerable plaque and in the stratification of patients in whom HDL-mimetic therapy may have a clinical benefit.

Nanoparticles have the potential to drive completely new applications in molecular imaging, targeted therapy, and theranostics in human disease. Defined as specifically engineered particles that are 1 to 100 nm in at least 1 dimension, nanoparticles have been applied in clinical applications in cancer where they display improved sensitivity in detection of liver metastasis and better tissue characterization of colorectal lesions (1). Oncology has employed them due to their diverse multifunctionality (e.g., modification for localized therapy), high payload capacity, and targeting capability (1), yet these state-of-the-art developments have yet to capture major attention in the cardiovascular disease (CVD) field.

HDL represents a promising “building block,” which could form the basis of a successful CVD nanoparticle because: 1) they are naturally-occurring, circulate-freely, and are biocompatible/biodegradable (1); 2) they may be intrinsically therapeutic via their cholesterol efflux properties 1, 2, 3; 3) they may target inflammatory intraplaque macrophages and monocytes 1, 3; and 4) they can be engineered to serve as “nanocarriers” for delivering both imaging and therapeutic payloads. However, HDL is not necessarily deliverable in sufficient quantities to every patient’s plaque site(s).

In a new study in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, Pérez-Medina et al. (4) advanced their pursuit of this target by generating a positron emission tomography (PET)-imageable HDL nanoparticle via incorporation of the radioisotope 89Zr. The team reconstituted synthetic discoidal HDL nanoparticles consisting of the primary constituents of HDL, apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) and the phospholipid phosphocholine. Two differently radiolabeled HDL nanoparticles were developed, one in which the chelator for binding 89Zr was conjugated to ApoA-I and in the other, conjugated to phosphocholine. 89Zr-ApoA-I and phosphocholine-89Zr nanoparticles were used to validate delivery to atherosclerotic sites, quantify biodistributions, and identify which nanoparticle type better targets atherosclerotic plaques. For translation, the investigators employed 3 different animal models of atherosclerosis, all fed high fat diets—an ApoE−/− murine model; a New Zealand white rabbit model with a double balloon injury of the thoracic and abdominal aorta; and a familial hypercholesterolemia porcine model with balloon injuries on the deep and superficial femoral arteries (Central Illustration).

In all the animal models, the target organs for HDL nanoparticles were identical, with the kidneys the primary accumulation site, but with consistent localization in atherosclerotic plaque, as well. In mice, atherosclerotic plaque uptake was significant only for phosphocholine-89Zr particles (p = 0.02) compared with wild-type controls with an ∼50% signal increase (4). In rabbits, plaques were targeted again only by phosphocholine-89Zr particles at ∼100% above control animals as quantified by PET. In pigs, phosphocholine-89Zr particles allowed visualization of atherosclerosis, with a trend of increased uptake in plaque, compared with controls.

In parallel with the PET studies, the authors employed fluorophore (DiR)-loaded HDL nanoparticles to show uptake into atherosclerotic macrophages and inflammatory monocytes in mice via flow cytometry. Macrophages and Ly-6Chi monocytes took up HDL nanoparticles ∼3- to 4.5-fold over other plaque cells such as neutrophils (4). This may be insufficient to engender suitably large differences in signal when performing macroscopic imaging such as PET, consistent with the signal observed in the animal studies (4). This is likely related to HDL nanoparticle targeting, a function of their inability to penetrate deeply into plaques because: 1) atherosclerotic plaque permeability variation may preclude free apoA-I HDL from accessing advanced plaques (2); and 2) selective targeting in blood circulation is insufficient to enable cellular uptake (dendritic cells in blood were targeted more than Ly-6Chi monocytes [4]) and plaque penetration. However, the fact that those inflammatory cells that go on to become M1 macrophages and foam cells may be precisely targetable is an important finding that could allow for “Trojan Horse” treatment with deep penetration of the atherosclerotic plaque in the future (5).

Translational Relevance

Although reduced HDL levels are unequivocally associated with increased risk for CVD, a number of studies suggest HDL may not be causal for CVD (3). These include sophisticated Mendelian randomization studies and several clinical trials that suggest raising HDL levels does not necessarily prevent heart attacks and strokes, thereby calling the “HDL hypothesis” into question. Instead, investigators are now focused on the “HDL flux hypothesis” and finding ways to deliver sufficient functional HDL (which may induce reverse cholesterol transport to macrophages) to diseased vessels. Yet HDL accumulation is notably complex compared with typical nanoparticles—instead of getting trapped, they recirculate through the lymph and display a relatively long half-life (2). HDL, therefore, does not accumulate in plaque, but reaches a steady state, and given clinical PET spatial resolutions (several millimeters), it can be challenging to spatially distinguish particles in the vessel wall compared with those in blood.

Nevertheless, molecular imaging approaches such as those shown here may be useful to help stratify patients and determine which ones will accumulate high levels of a desired therapy. “Pre-testing” using replica-reporter agents may be particularly desirable if the drug of interest is expensive or has side effects that one would wish to avoid in a “nonresponder.” Additionally, nanoparticles such as modified HDL can be bioengineered to achieve enhanced therapeutic effect. For example, it may be that those subfractions of HDL that cause the largest increases in cholesterol efflux could be conjugated to the nanoparticles that accumulate in M1 macrophages. Modified theranostic nanoparticles (AGuIX, activation and guiding of irradiation by X-ray) are now being evaluated in French Phase 1 clinical trials for cancer imaging and radiotherapy (Radiosensitization of Multiple Brain Metastases Using AGuIX Gadolinium Based Nanoparticles [NANO-RAD]; NCT02820454). They home to brain metastases to sensitively detect (using magnetic resonance imaging) and deliver radiosensitization for radiation therapy. The hope is that similar advances will occur in the field of cardiovascular medicine, and allow targeted treatment of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque.

Footnotes

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

All authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Basic to Translational Scienceauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Smith B.R., Gambhir S.S. Nanomaterials for in vivo imaging. Chem Rev. 2017;117:901–986. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng K.H., van der Valk F.M., Smits L.P. HDL mimetic CER-001 targets atherosclerotic plaques in patients. Atherosclerosis. 2016;251:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqi H.K., Kiss D., Rader D. HDL-cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2015;30:536–542. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez-Medina C., Binderup T., Lobatto M.E. In vivo PET imaging of HDL in multiple atherosclerosis models. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2016;9:950–961. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith B.R., Ghosn E.E.B., Rallapalli H. Selective uptake of single-walled carbon nanotubes by circulating monocytes for enhanced tumour delivery. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:481–487. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]