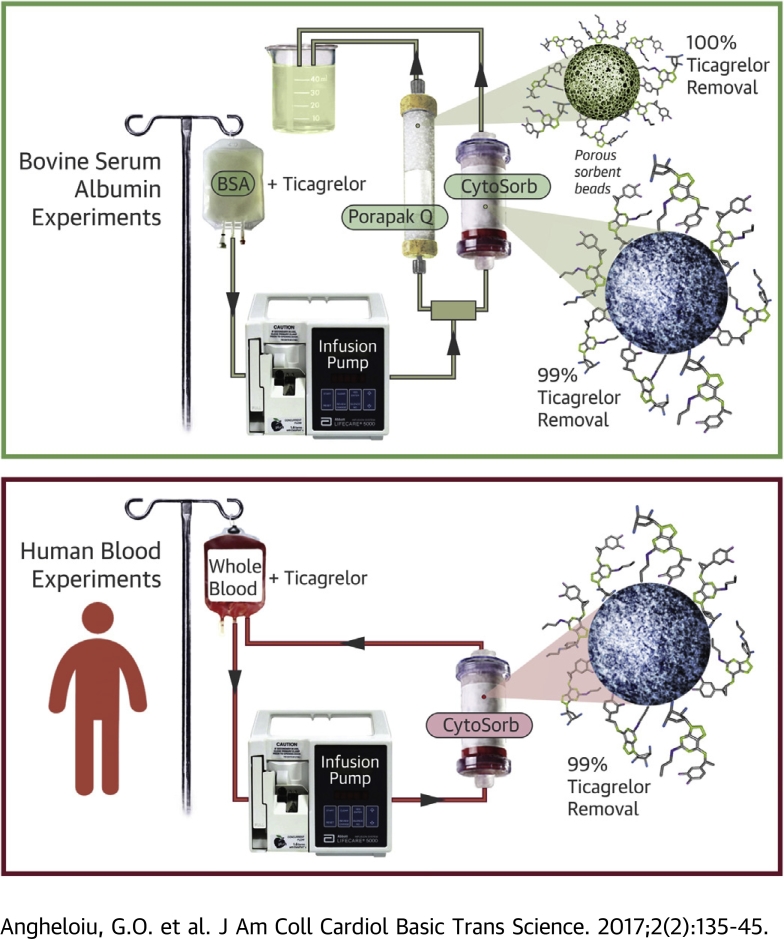

Visual Abstract

Key Words: concentration, drug, P2Y12, platelet, removal, sorbent, ticagrelor

Abbreviations and Acronyms: b.i.d., twice a day; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft

Highlights

-

•

Ticagrelor is reversibly bound to albumin.

-

•

CytoSorb and Porapak Q 50-80 mesh remove ticagrelor from bovine serum albumin solution with >99% efficiency.

-

•

CytoSorb removes ticagrelor from human blood and human plasma with >99% efficiency.

Summary

The authors devised an efficient method for ticagrelor removal from blood using sorbent hemadsorption. Ticagrelor removal was measured in 2 sets of in vitro experiments. The first set was a first-pass experiment using bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution pre-incubated with ticagrelor, whereas the second set, performed in a recirculating manner, used human blood mixed with ticagrelor. Removal of ticagrelor from BSA solution reached values >99%. The peak removal rate was 99% and 94% from whole blood and 99.99% and 90% from plasma during 10 h and 3 to 4 h of recirculating experiments, respectively. In conclusion, hemadsorption robustly removes ticagrelor from BSA solution and human blood samples.

Coronary artery disease is a prevalent condition in the industrialized countries, with high morbidity and mortality. Antiplatelet treatment is a recommended therapy in coronary artery disease and spontaneous or post-operative bleeding is a risk of antiplatelet therapy.

Ticagrelor is a potent P2Y12 receptor antagonist. In the treatment of acute coronary events, ticagrelor has shown a significant reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke as demonstrated by the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial, and it is recommended to be loaded in the emergency department prior to cardiac catheterization (1). On average, 10% to 11% of patients who undergo cardiac catheterization and are on antiplatelet therapy will proceed to have coronary aortic bypass graft (CABG) 1, 2.

The rate of major bleeding in ticagrelor as well as clopidogrel-treated patients in the PLATO trial was similar: 11.6% and 11.2%, and 81% among patients undergoing CABG 1, 3. Platelet transfusion is not a complete solution due to the remaining amount of drug present in the circulation that can redistribute and inhibit the new platelets. Because ticagrelor is reversibly bound to P2Y12 and plasma proteins, removing the drug from the systemic circulation by means of sorbent technology could reverse the drug-induced antiplatelet effect.

The bleeding rate with ticagrelor is not known for types of surgery other than cardiothoracic. Two case reports indicate spontaneous bleeding with ticagrelor (abdomen and lung) 4, 5 that required surgery, and a relatively small study showed increased rate of bleeding with abdominal surgery needing transfusion with a different class of antiplatelet medication—clopidogrel, a thienopyridine (6). A similar bleeding risk profile was documented during CABG between ticagrelor and clopidogrel (1). As a consequence, current guidelines require at least 5 days’ ticagrelor discontinuation prior to elective surgeries of any type—thoracic or abdominal—in a similar manner with clopidogrel (7).

Dialysis is not a viable removal route, because 99.8% of ticagrelor is protein-bound. Other P2Y12 receptor antagonists (clopidogrel and prasugrel) have similar albumin-biding affinities (98%) (8), whereas aspirin has a lower affinity to proteins (58%) (9).

Our group has demonstrated that various sorbent beads (e.g., CytoSorb, Cytosorbents, Monmouth Junction, New Jersey; Porapak Q 50-80 mesh, Supelco, Bellefonte Pennsylvania) can adsorb iodinated contrast molecules such as iodixanol and iohexol with a peak removal rate of 95%, as well as dabigatran 10, 11. These molecules contain several hydroxyl groups linked to nitrogen atoms and central hydrophobic structures (benzene rings). In a similar way, the ticagrelor molecule contains hydroxyl and nitrogen radicals attached to a central hydrophobic ring, and it is possibly able to link through similar bonds with the styrene copolymers. We hypothesize that ticagrelor can be adsorbed by CytoSorb and Porapak Q 50-80 mesh sorbent beads from albumin solution and human blood, creating the premises of a unifying method able to remove molecules representative of 3 classes frequently used in cardiology—antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and radiocontrast agents.

Methods

Porapak Q 50-80 mesh and CytoSorb (graciously donated by Cytosorbents) are styrene copolymer with bead diameters of 125 to 149 and 425 to 1,000 μm and surface area of 550 and 850 m2/g, respectively. In the current study, both sorbents were separately used to remove ticagrelor from bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution in normal saline, whereas CytoSorb was used also to remove the drug from human blood samples.

Definitions

Ticagrelor removal is a value expressed in percentages and equal to the ratio (affluent concentration − effluent concentration)/(affluent concentration) where the affluent and effluent concentrations are the ticagrelor concentration entering and exiting the sorbent column, respectively. Mixed and adsorbed BSA solution or blood refers to the vehicle solution (BSA solution or blood), respectively, after drug incubation and after being adsorbed through the sorbent column at various intervals. The filtration velocity expressed as output in ml/min represents the velocity of the fluid vehicle (BSA solution or human blood) carrying the drug and being driven by the perfusion pump and circulated through the 2 circuits shown in Figures 1A and 1B.

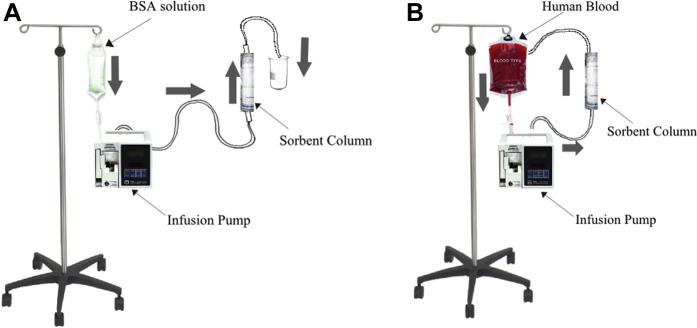

Figure 1.

Experimental Setup for Ticagrelor Removal From BSA Solution and Human Blood

Experimental setup for ticagrelor removal from BSA solution (A) and human blood (B). BSA, bovine serum albumin.

Bovine serum albumin experiments

BSA solution was prepared by mixing at room temperature heat shock–isolated BSA (Amresco, Solon, Ohio) with normal saline, resulting in a 4% (4 g/dl) and 0.4% BSA solution. The solution was kept at −20°C until use when it was passively thawed. A 0.01 mg/ml (19.14 μmol/l) ticagrelor-BSA mix was used, higher than the mean maximum and minimum plasma concentration in blood following 4 weeks of treatment (90 mg twice a day) of 1.5 μmol/l (770 ng/ml) and 0.4 μmol/l (227 ng/ml), respectively (12). The solution was prepared by mixing the drug with BSA solution and incubating the mix for approximately 30 min prior to use at room temperature. If drug-BSA solution was to be used at a later date, the mix was immediately stored at −20°C after incubation and then passively thawed before experiments. The 4% BSA solution-ticagrelor mix was used in removal experiments with Porapak Q 50-80 mesh and also CytoSorb. To gauge the influence of the BSA dilution (4% vs. 0.4%), CytoSorb was also used comparatively in removing ticagrelor from 0.4% BSA solution.

The BSA-ticagrelor experiments were performed in a first-pass manner (Figure 1A). The BSA-ticagrelor solution mix was housed in a 1-l perfusion bag and pushed with a velocity of 1 ml/min by a Lifecare 5000 Infusion System pump (Abbott, Green Oaks, Illinois) in 3 independent sets of experiments through sorbent columns of, respectively, 10-ml, 20-ml, and 40-ml capacity (containing an average 4.1, 13.2, and 23.7 g of CytoSorb and 4.4, 7.8, and 27.1 g of Porapak Q 50-80 mesh, respectively) after careful deaeration and priming of the tubing lines. The drug vehicle was transferred through the sorbent column in an antigravitational manner 10, 11. Each BSA experiment lasted 100 min. The resulting filtrate was collected in jars from which samples were taken for drug measurement assays at the end of each first-pass experiment.

Blood experiments

This set of experiments was performed in 3 models presented here, using either blood collected remotely from healthy volunteers (BioreclamationIVT, Hicksville, New York) and used at least 24 h later while being shipped and stored at 4°C, or samples freshly collected from 1 healthy volunteer and used within the following 60 min at room temperature. Blood was anticoagulated on collection with Na heparin 15 U/ml. At the start of the experiments, blood was mixed with ticagrelor and then left to incubate at room temperature for approximately 30 min. Blood experiments were performed in 3 independent experiments remotely mimicking the vascular system flow (Figure 1B) with the blood being housed in a 1-l perfusion bag and pushed by a Lifecare 5000 Infusion System pump through the sorbent columns in an antigravitational manner 10, 11 and from there back into the perfusion bag, after initial careful deaeration and priming of the tubing lines. Blood specimens were collected from the initial blood-drug mix and then every h from the perfusion bag. All blood as well as BSA samples were then stored and shipped at −20°C on dry ice, respectively, to the laboratory chosen to test the drug concentration.

Model 1

In this model, 250 ml blood from BioreclamationIVT was mixed with 9.2 mg of ticagrelor and passed at a velocity of 9 ml/min through 14 10-ml columns housing a total of 59 g of CytoSorb and mounted in series for a total of 10 h.

Model 2

In this model, 500 ml of blood from BioreclamationIVT was mixed with 18.1 mg of ticagrelor and passed at a velocity of 17 ml/min through a column housing 300 ml of CytoSorb (158 g) for a total of 10 h.

Model 3

In this model, 250 ml of freshly collected blood (from a healthy volunteer) was mixed with 9.2 mg of ticagrelor and passed at a velocity of 3 ml/min for the first 5 h through 12 10-ml columns mounted in series and containing a total of 120 ml of CytoSorb and for the remaining 5 h through 14 fresh 10-ml series-mounted columns containing 140 ml of fresh CytoSorb. All 26 columns used in this model contained a total of 113 g of sorbent. The average calculated whole blood experimental mixed concentration in the three models was 70 ± 0.69 μmol/l (70.4, 69.2, and 70.4 μmol/l, respectively).

While it is known that the mean maximal plasma exposure in patients following a loading dose of 180-mg ticagrelor is lower, 931 ng/ml (1.78 μmol/l) (12), we used high in vitro drug concentrations specifically for exploring the concept of ticagrelor removal in these 3 experimental models, allowing us to demonstrate an impressive removal efficiency. At the same time, we employed a high mass of ticagrelor with the objective of assessing the amount of sorbent needed to remove the entire ticagrelor mass from circulation after a clinical loading scenario. After a loading dose, the clinical mean maximal concentration is 931 ng/ml (1.78 μmol/l), hence the total amount of ticagrelor in the human body is 82 mg for a distribution volume of 88 l (12).

The perfusion bag was slowly and constantly agitated during this experiment by an agitator (Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, Iowa) mounted vertically on the pole supporting the perfusion bag and the pump.

All blood experiments were performed in 1 run for each filtration velocity and model of experiment.

Blood sample collection

For all blood experiments, drug assays were completed from 2 to 3 ml of samples. These samples were collected from the mixed blood, as well as from the adsorbed blood after each h of experiment. A complete blood count was measured in model 3 using 2 to 3 ml of blood collected in EDTA (purple top) tubes from the initial and mixed samples, as well as from the adsorbed samples at 5 and 10 h on a XN-3000 Sysmex analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan).

Ticagrelor concentrations were measured in the drug-solution mix where the solution was either the BSA solution or blood, as well from the BSA and whole blood adsorbed samples in models 1 and 2 of blood experiments. Drug concentrations were measured in both whole blood as well as plasma in the drug-solution mix as well as adsorbed samples in model 3. Plasma was separated at approximately 2,200 to 2,800 rpm for 15 min on a Dade Immunofuge II centrifuge (Baxter, Deerfield, Illinois). Samples were stored at −20°C and shipped in dry ice.

Ticagrelor assay

Ticagrelor concentration in BSA solution, plasma and whole blood was measured using a liquid chromatography technique with tandem mass spectrometric detection (13). All aliquots belonging to each particular experiment were performed in same assay batch. To 500 μl of each sample, 1 ml acetonitrile was added, vortexed at room temperature for 10 min, and centrifuged at 2,000g for 15 min at 20°C. The supernatant was evaporated to dryness then redissolved in 1 ml of 50% methanol containing 5 mmol/l ammonium formate and 100 fmol/ml verapamil for analysis.

A calibration curve was measured for ticagrelor using synthetic standard from 4.6 fmol/ml to 4.6 nmol/ml. Each calibration point contained 100 fmol/ml of verapamil as an internal standard.

Instrumentation

An Agilent 6490 QQQ with I-Funnel technology fitted with a Jet Stream electrospray ionization source (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California), coupled with an Agilent 1290 UHPLC system was used. A Phenomenx Kinetex C18 (Torrance, California) 2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8-μm particle size was used for chromatography.

All computations regarding ticagrelor removal were performed using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy assay-measured concentrations. Measurements of concentrations in aliquots from same experiments were performed in same assay batch ensuring accurate whole blood and plasma ticagrelor percentage sorbent-removal rates.

To assess how much albumin was adsorbed by the 2 sorbents, BSA concentration measurement was performed using the BSA absorption properties at 595 nm on a Shimadzu Corporation UV-2401PC spectrometer (Kyoto, Japan), according to a method put forth by the University of Michigan and attached here (Supplemental Appendix).

Statistics

Student t test for paired sets was used for multiple numerical variables analysis (Open Office 3.1, The Apache Software Foundation, Los Angeles, California).

Results

Bovine serum albumin experiments

Ticagrelor was efficiently removed in a first-pass experiment by the 2 sorbents, with 99% and 100% maximum removal for the CytoSorb and Porapak Q 50-80 mesh, respectively (Figures 2A and 2B).

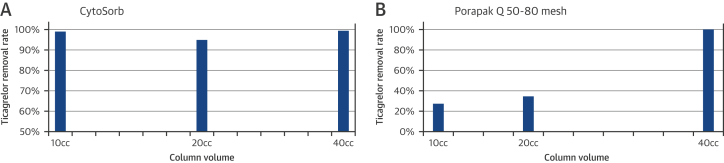

Figure 2.

Removal Rate of Ticagrelor From a 4% BSA Solution

Removal rate of ticagrelor from a 4% BSA solution using various volumes of sorbent—CytoSorb (A) and Porapak Q 50-80 mesh (B)—in a first-pass experiment. Abbreviation as in Figure 1.

Ticagrelor concentration dropped with the 10-, 20-, and 40-ml sorbent columns from 19.14 μmol/l to 0.21, 0.99 and 0.17 μmol/l, respectively, using CytoSorb (p = 0.0002).

There was no difference in ticagrelor removal with the 10-, 20-, and 40-ml CytoSorb columns between the 0.4% versus 4% BSA solutions (average 96 ± 5% vs. 94 ± 4%; p = 0.86).

BSA concentration showed an average 9.6% drop for the entire range of columns' volumes.

Blood experiments

Because the study reached close to 100% ticagrelor removal in BSA solution, we pursued a second phase looking at ticagrelor removal in human blood.

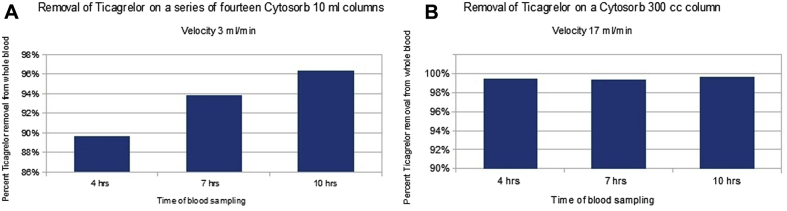

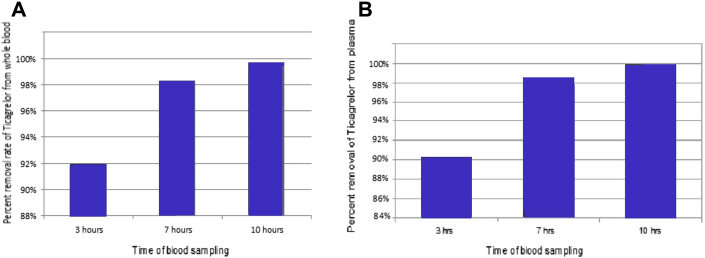

In a manner similar to the BSA experiments, ticagrelor whole blood concentration was reduced by a maximum of 96% in model 1 and 99% in model 2 using CytoSorb (Figure 3) at 10 h of a recirculating experiment. We employed 2 different structures of columns (a series of 10-ml columns vs. a single 300-ml column), mass of sorbents (59 g vs. 158 g) and filtration velocities (3 ml/min vs. 17 ml/min). At 3 and 7 h, the removal rate was 90% and 94%, respectively, in model 1, and flat 99% in model 2.

Figure 3.

Removal Rate of Ticagrelor From Whole Human Blood

Removal rate of ticagrelor from whole human blood purchased from a blood bank during a recirculating experiment using CytoSorb in 2 models, on 14 10-ml columns mounted in series (model 1) (A) or 1 300-ml column (model 2) (B).

The largest column (300 ml), used in model 2, removed >99% of ticagrelor from whole blood in the first 3 h (Figure 3B).

At baseline, the average mixed whole blood ticagrelor concentration in the 3 models was 70 ± 0.69 μmol/l (70.4, 69.2, and 70.4 μmol/l in each of the 3 models, respectively), whereas the drug concentration at 3 to 4 h of recirculating experiment was 4.41 ± 3.59 μmol/l (7.25, 0.38, and 5.6 μmol/l, respectively; p = 0.0007 in comparison to baseline). At 10 h, the same parameter was 1.01 ± 1.35 μmol/l (2.57, 0.24, and 0.21 μmol/l; p = 0.0001 in comparison to baseline).

In model 3 of blood experiments, ticagrelor concentration in fresh separated plasma (collected <60 min prior to use) decreased from a mixed sample concentration of 67.36 to 0.036 μmol/l, indicating a maximum removal rate at 10 h into the experiment of 99.99%, respectively (Figure 4A). The removal rate in plasma was 90% and 98.5%, respectively (Figure 4B) at 3 and 7 h, time intervals suited for settings such as CABG operations where the surgery would take as long as these intervals.

Figure 4.

Removal Rate of Ticagrelor From Whole Human Blood and Plasma

Removal rate of ticagrelor from whole human blood (A) and plasma (B) freshly (<60-min interval until being used) collected during model 3 of the blood recirculating experiment using CytoSorb.

When we analyzed all 3 experiments using human whole blood together, ticagrelor removal was on average 94% between the mixed samples and the adsorbed samples at 3 or 4 h of removal process, 3.5% between the adsorbed samples at 3 or 4 h and those at 7 h and 1.4% between the samples at 7 h and those at 10 h, with an average 94%, 97.5%, and 99% removal rates at these 3 intervals of time. There was a significant statistical difference in terms of percentage of ticagrelor removal between the first interval of time and the other 2 intervals (p = 0.003 and 0.002, respectively), with no significant difference between the latter 2.

The blood cell count in the model 3 blood experiment showed a relatively minor drop in red cells and hemoglobin and an expected decrease in the platelet and white cell counts (13). The erythrocyte and hemoglobin concentrations as well as the leukocyte and platelet concentrations dropped from a baseline set of 4.7 × 106/μl, 14.5 g/dl, 4.6 × 103 and 276 × 103/μl, respectively, to 4.3 × 106/μl (9% drop from baseline), 12.5 g/dl (14%), 1.3 × 103 (72%) and 78 × 103/μl (72%) at 5 h into the recirculating experiment and 4.5 × 106/μl (4% drop from baseline), 12.1 g/dl (17%), 1.1 × 103 (76%) and 59 × 103/μl (79%), respectively, at 10 h. Platelets and leukocytes have a short life span outside of the body, <4 h, hence our findings are in agreement with this particular knowledge.

Discussion

Supported by clinical evidence, ticagrelor is approved to reduce major cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome and in patients with prior myocardial infarction 1, 14. Its primary mechanism of action is as a direct acting drug, reversibly binding the P2Y12 platelet receptor and inhibiting subsequently the adenosine diphosphate–induced platelet activation. In addition to P2Y12, ticagrelor also inhibits the equilibrative nucleoside transporter-1, thereby providing an enhanced adenosine response 15, 16. In this in vitro study, we used 2 sorbents to demonstrate efficient removal of ticagrelor in albumin solution as well as from human blood.

Removal efficiency

Bovine serum albumin experiments

We succeeded in removing ticagrelor using both CytoSorb and Porapak Q 50-80 mesh from BSA solution. As expected adsorption was seemingly better using higher masses of sorbent (Figures 2A and 2B). Ticagrelor is 99.8% bound to albumin (17), and the fact that the peak removal rate for the 2 sorbents was 99% and 100%, respectively (Figure 2), suggests that both sorbents were able to remove ticagrelor from the albumin molecules.

Varying the concentrations of albumin (4% vs. 0.4% BSA) did not significantly change the drug removal efficiency. Possibly the large difference in molecular mass between BSA and ticagrelor (66,000 Da vs. 522 Da) caused the 2 molecules to be absorbed on different sites on the copolymers' structure. Alternatively, one can imagine that the BSA-ticagrelor competitive absorption might have already taken place at low BSA titers, and this process then plateaued at higher BSA levels.

The BSA removal by sorbent was approximately 9.6%. Particular attention should be given to selecting patients with a normal albumin during the clinical use of our device, or appropriately replacing the mass of albumin removed if clinically indicated.

Human blood experiments

Ticagrelor was efficiently removed both from plasma and whole blood using various masses of sorbent and 2 different column architectures, with possibly better removal rates at longer intervals of time. The most substantial removal from blood takes place in the first 3 to 4 h (94%) with a nonsignificant increase in the next 6 to 7 h.

It appears, however, that a higher mass of sorbent (158 vs. 59 g CytoSorb between model 2 and model 1) improved the removal rate (99% vs. 96%) (Figures 3B and 3A, respectively), irrespective of the higher filtration velocity in model 2 versus model 1 (17 ml/min vs. 3 ml/min) (10). More importantly, the largest column (300 ml, containing 158 g of CytoSorb), used in model 2, removed >99% of ticagrelor from whole blood in the first 3 h (Figure 3B). Multiple runs with various masses of sorbent and filtration velocities are desirable in the future to demonstrate significant difference between various masses of sorbent.

A larger interaction of the drug with the sorbent beads, either by a longer exposure (as in model 3 of the blood experiments) (Figure 4) or by exposing the same mass of drug (1 mg) to increasing volumes of sorbent (Figure 2 for BSA experiments) has resulted naturally in a better removal of ticagrelor. There was no difference in tubing priming and deaeration between the various experiments.

The architecture of the sorbent column was not necessarily as important, because a combination of smaller columns stacked in series in model 3 was not overwhelmingly better than a single larger column (model 3: 99.7% removal with 113 g of CytoSorb vs. model 2: 99% removal with 158 g of sorbent) (Figures 4A and 3, respectively). At the same time, exposing the ticagrelor at 5 h in mid-experiment to a fresh volume of sorbent did not change the result (Figures 3 and 4A, respectively).

Clinical significance

In patients, the mean maximum and minimum plasma concentration in blood following 4 weeks of treatment (90 mg twice a day) is 1.5 μmol/l (770 ng/ml) and 0.4 μmol/l (227 ng/ml), respectively (12). A high plasma concentration of ticagrelor (67.36 μmol/l) was used specifically to explore the concept of ticagrelor removal in vitro, allowing us to demonstrate an impressive removal efficiency. At the same time, we were able to assess the amount of sorbent needed to remove ticagrelor from circulation in a clinical loading scenario. After a loading dose (180 mg), the clinical mean maximal concentration is 931 ng/ml (1.78 μmol/l), hence the total amount of ticagrelor in the human body is 82 mg for a distribution volume of 88 l in an average patient (12). We were able in model 2 of blood experiments to remove 18 mg of ticagrelor using a 300-ml column containing 158 g of sorbent. Subsequently approximately 5 300-ml columns with a total sorbent mass of 790 g will eventually be needed to remove 82 mg of drug in a clinical experiment.

Our method was able to reduce ticagrelor levels in plasma, extracted from samples of blood pre-incubated with a plasma supratherapeutic ticagrelor concentration of 67.36 μmol/l, to a concentration level of 0.036 μmol/l, close to the one-half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for inhibition of adenosine diphosphate–induced platelet aggregation in vitro (0.022 μmol/l) (18). Starting from lower drug concentrations will likely lead to final drug levels much below this threshold. In this study, we used high baseline concentration drug levels with the distinct objective of quantifying the sorbent mass need to absorb the ticagrelor found in an average patient after a ticagrelor loading dose.

This study had to answer a fundamental initial question: do sorbents bind ticagrelor molecules? Sorbents do not necessarily bind drug molecules in a universal fashion, with some drugs having high affinity for sorbent beads and others demonstrating no interaction at all. Our group showed an excellent capacity of sorbents to bind and remove ticagrelor (>99% in plasma and whole blood as well as BSA). The free ticagrelor fraction is part of the plasma-soluble drug; therefore, we assume that sorbents may have a similar effect on the free plasma ticagrelor component and finally on the platelet aggregability recovery (19). To fully prove our method's clinical effect, one will need in the future results of platelet aggregability tests to demonstrate aggregability recovery after ticagrelor removal, which was not the present study's objective. At the same time, experiments comparing the sorbent versus monoclonal antibody approaches for ticagrelor removal or reversal can be considered for future studies (19).

A specific monoclonal antibody reversal agent for ticagrelor has been identified and its pharmacology has been characterized in vitro as well as in vivo (19). As a complement to this new development, our method could be applied during a clinical scenario that may involve a patient loaded with ticagrelor in the emergency department, undergoing cardiac catheterization and then referred immediately to open heart surgery. Ticagrelor removal would start and continue through surgery, mostly because the patient will be on a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, which would allow continuous recirculation of the blood through the sorbent column.

The filtration velocities used in our study are below those used in double-lumen peripherally inserted central catheter lines (20 ml/min through 1 lumen of the double peripherally inserted central catheter) and could create the premises for a venovenous removal method in patients with clinically significant hemorrhage or prepped to undergo urgent surgery.

In bench experiments, CytoSorb has also been shown to absorb 99% of dabigatran in albumin solution (20) and up to 96% of radiocontrast 10, 11, creating the premises of a possible all-inclusive method of ticagrelor, anticoagulant, and radiocontrast removal method.

Many times, cardiac patients can be on both an antiplatelet and an anticoagulant medication, and sorbent hemadsorption will possibly be able to simultaneously remove both types of agents in any of the previously mentioned scenarios.

Sorbents are nonspecific media for drug removal and one needs to determine whether drugs used during CABG or vascular surgery are being removed by sorbents. Of particular interest are aspirin and heparin that are needed, respectively, to prevent acute thrombosis of arterial anastomoses and extracorporeal circuits, sevoflurane, the most commonly used general anesthesia gas, and protamine. Protamine is used only at the end of surgery, when the ticagrelor removal process would have ended already, and aspirin binds irreversibly to platelets. Whereas heparin is not being adsorbed by CytoSorb (data on file with Cytosorbents), sevoflurane can be measured by a sorbent gas trap (21). Future studies need to assess the interaction between CytoSorb or Porapak Q 50-80 mesh and sevoflurane, followed by establishing a protocol for dose adjustment.

CytoSorb is a biocompatible sorbent already used in the clinical practice for removing cytokines during CABG operations to alleviate the post-surgical inflammatory response (22). This assumes no significant effect on the platelet and leukocyte count in vivo. Hence, in our setup, the blood is circulated directly through the sorbent (in our text and Träger et al. [22]), avoiding in this way the costs incurred by plasma separation in plasmapheresis. The circulating system is already in place in the potential case of removing ticagrelor during CABG, represented by the cardiopulmonary bypass machine.

Interestingly the drop in albumin was rather minor (<10%) in comparison to an almost complete removal of ticagrelor. Importantly albumin interacts mostly through hydrophilic bonds (23), whereas styrene copolymers interact mostly through hydrophobic van der Walls and hydrogen bonds, explaining the differential sorbent absorption of ticagrelor versus albumin.

Initiating our experiments from lower drug concentration levels would recreate the removal process starting from a value achieved intermediary in the course of the experiments described, because the lowest plasma levels reached in model 3 was 0.036 μmol/l (starting from a baseline of 67.36 μmol/l), much below the mean minimum clinical plasma concentration of 0.4 μmol/l (12).

Study limitations and further plans

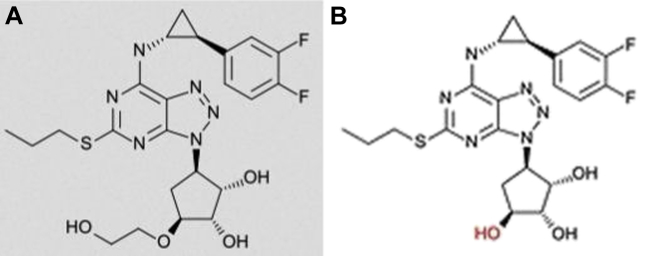

Although 1 of our experiments used freshly collected blood rich in leukocytes and platelets, the study was not geared toward studying separately the removal of ticagrelor from platelets—the most important cell type targeted by a P2Y12 antagonist. Whereas the AR-C124910XX removal was not studied here, this ticagrelor metabolite with similar antiplatelet potency as the parent drug has a structure fully resembling that of ticagrelor, with only a slight difference (a hydroxy-ethyl branch) and conceivably can be equally removed from blood (Figure 5) (24). Further studies need to address these facets of the ticagrelor removal process.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX Structures

Comparison of ticagrelor (A) and main metabolite AR-C124910XX (B) structures.

Whereas platelets are the active cellular units interacting with ticagrelor, erythrocytes are the most abundant cell type and interact with P2Y12 receptor antagonist molecules as well (25). Further studies are needed to assess the partition of ticagrelor between plasma and blood cells, in particular platelets and erythrocytes, because the latter represent a large pool of equilibrative nucleoside transporter-1 transporters to which ticagrelor binds.

All blood experiments were performed in single runs. Results nonetheless were concordant among the 3 models with increasing removal rates for longer experimental time intervals. Multiple experimental runs with varying sorbent masses, filtration velocities, or filtration times are needed in future studies to show that higher volumes of sorbent are statistically better than lower volumes, or to demonstrate that adsorption longer than 4 h would result in significantly better removal rates than just 3 to 4 h of hemadsorption. These particular objectives were not goals of this study.

Conclusions

Ticagrelor was removed by >99% from BSA solution, human plasma, and whole blood during bench hemadsorption experiments. The most robust removal process takes place in the first 3 to 4 h of hemadsorption. Our results create the premises of a unifying method able to remove representative molecules from 3 classes of agents—antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and radiocontrast—and can complement the use of a newly developed specific monoclonal antibody reversal agent for ticagrelor (19).

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Our method could be applied during a clinical scenario that may involve a patient loaded with ticagrelor in the emergency department, undergoing cardiac catheterization and then referred immediately to open heart surgery. Ticagrelor removal would start and continue through surgery, mostly because the patient will be on a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, which would allow continuous recirculation of the blood through the sorbent column. In a second scenario, of vascular surgery, the blood is bypassed through a shunt to avoid bleeding in the area served by the artery operated on. Similarly with the first scenario, the shunted blood can be directed to a sorbent column before being sent back to the patient.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Our method was able to reduce plasma ticagrelor from supratherapeutic concentrations to levels close to the IC50 for inhibition of adenosine diphosphate–induced platelet aggregation in vitro. We showed an excellent capacity of sorbents to bind and remove ticagrelor (≥99% in plasma and whole blood). In bench experiments, CytoSorb has also been shown to absorb 99% of dabigatran in albumin solution and up to 96% of radiocontrast, creating the premises of a possible all-inclusive method of ticagrelor, anticoagulant, and radiocontrast removal method. Many times, cardiac patients can be on both an antiplatelet and an anticoagulant medication, and sorbent hemadsorption will possibly be able to simultaneously remove both types of agents in any of the previously mentioned scenarios.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ian Gilchrist, Alyssa Hawranko, and Renato DeRita for insight and logistic support and to Sven Nylander and Karen McFadden for manuscript revision and editorial support.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from AstraZeneca and AstraZeneca provided ticagrelor for this study. Dr. Whatling is an employee of AstraZeneca. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

All authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Basic to Translational Scienceauthor instructions page.

Appendix

References

- 1.Wallentin L., Becker R.C., Budaj A., for the PLATO Investigators Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebrahimi R., Dyke C., Mehran R. Outcomes following pre-operative clopidogrel administration in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1965–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Held C., Asenblad N., Bassand J.P. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: results from the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:672–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng V.E., Oppermen A., Natarajan D., Haikerwal D., Pereira J. Spontaneous omental bleeding in the setting of dual anti-platelet therapy with ticagrelor. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23:e115–e117. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitmore T.J., O'Shea J.P., Starac D., Edwards M.D., Waterer G.W. A case of pulmonary hemorrhage due to drug-induced pneumonitis secondary to ticagrelor therapy. Chest. 2014;145:639–641. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chernoguz A., Telem D.A., Chu E., Ozao-Choy J., Tammaro Y., Divino C.M. Cessation of clopidogrel before major abdominal procedures. Arch Surg. 2011;146:334–339. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitchett D., Mazer C.D., Eikelboom J., Verma S. Antiplatelet therapy and cardiac surgery: review of recent evidence and clinical implications. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:10427. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganesan S., Williams C., Maslen C.L., Cherala G. Clopidogrel variability: role of plasma protein binding alterations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:1468–1477. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghahramani P., Rowland-Yeo K., Yeo W.W., Jackson P.R., Ramsay L.E. Protein binding of aspirin and salicylate measured by in vivo ultrafiltration. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:285–295. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angheloiu G.O., Hänscheid H., Reiners C., Anderson W.D., Kellum J.A. In vitro catheter and sorbent-based method for clearance of radiocontrast material during cerebral interventions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2013;14:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angheloiu G.O., Hänscheid H., Wen X., Capponi V., Anderson W.D., Kellum J.A. Experimental first-pass method for testing and comparing sorbent polymers used in the clearance of iodine contrast materials. Blood Purif. 2012;34:34–39. doi: 10.1159/000339816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storey R.F., Husted S., Harrington R.A. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by AZD6140, a reversible oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1852–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwanke U., Schrader L., Moog R. Storage of neutrophil granulocytes (PMNs) in additive solution or in autologous plasma for 72 h. Transfus Med. 2005;15:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonaca M.P., Bhatt D.L., Cohen M., for the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 Steering Committee and Investigators Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1791–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong D., Summers C., Ewart L., Nylander S., Sidaway J.E., van Giezen J.J. Characterization of the adenosine pharmacology of ticagrelor reveals therapeutically relevant inhibition of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:209–219. doi: 10.1177/1074248413511693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cattaneo M., Schulz R., Nylander S. Adenosine-mediated effects of ticagrelor: evidence and potential clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2503–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teng R., Oliver S., Hayes M.A., Butler K. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of ticagrelor in healthy subjects. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:1514–1521. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.032250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Pharmacology/Toxicology Review and Evaluation. NDA Number: 22-433. Center Receipt Date January 29, 2010. Product: Brilinta (ticagrelor). Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/022433Orig1s000PharmR.pdf. Accessed March 2017.

- 19.Buchanan A., Newton P., Pehrsson S. Structural and functional characterization of a specific antidote for ticagrelor. Blood. 2015;125:3484–3490. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-622928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angheloiu GO, van Ryn J, Goss AM. Removal of dabigatran using sorbent hemadsorption. Paper presented at: the Scientific Sessions of American Heart Association; November 7-11, 2015; Orlando, Florida.

- 21.Castellanos M., Xifra G., Fernández-Real J.M., Sánchez J.M. Breath gas concentrations mirror exposure to sevoflurane and isopropyl alcohol in hospital environments in non-occupational conditions. J Breath Res. 2016;10:016001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/1/016001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Träger K., Fritzler D., Fischer G. Treatment of post-cardiopulmonary bypass SIRS by hemoadsorption: a case series. Int J Artif Organs. 2016;39:141–146. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeyachandran Y.L., Mielczarski E., Rai B., Mielczarski J.A. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of adsorption/desorption of bovine serum albumin on hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir. 2009;25:11614–11620. doi: 10.1021/la901453a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nylander S., Schulz R. Effects of P2Y12 receptor antagonists beyond platelet inhibition—comparison of ticagrelor with thienopyridines. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:1163–1178. doi: 10.1111/bph.13429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonello L., Laine M., Kipson N. Ticagrelor increases adenosine plasma concentration in patients with an acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.