Rac1 is a small guanine nucleotide binding protein that cycles between an inactive GDP-bound and active GTP-bound state to regulate cell motility and migration. Rac1 signaling is initiated from the plasma membrane (PM).

KEYWORDS: electron microscopy; nanoclusters; phosphatidic acid; phosphoinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; plasma membrane; Rac1; signaling

ABSTRACT

Rac1 is a small guanine nucleotide binding protein that cycles between an inactive GDP-bound and active GTP-bound state to regulate cell motility and migration. Rac1 signaling is initiated from the plasma membrane (PM). Here, we used high-resolution spatial mapping and manipulation of PM lipid composition to define Rac1 nanoscale organization. We found that Rac1 proteins in the GTP- and GDP-bound states assemble into nonoverlapping nanoclusters; thus, Rac1 proteins undergo nucleotide-dependent segregation. Rac1 also selectively interacts with phosphatidic acid (PA) and phosphoinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), resulting in nanoclusters enriched in these lipids. These lipids are structurally important because depleting the PM of PA or PIP3 impairs both Rac1 PM binding and Rac1 nanoclustering. Lipid binding specificity of Rac1 is encoded in the amino acid sequence of the polybasic domain (PBD) of the C-terminal membrane anchor. Point mutations within the PBD, including arginine-to-lysine substitutions, profoundly alter Rac1 lipid binding specificity without changing the electrostatics of the protein and result in impaired macropinocytosis and decreased cell spreading. We propose that Rac1 nanoclusters act as lipid-based signaling platforms emulating the spatiotemporal organization of Ras proteins and show that the Rac1 PBD-prenyl anchor has a biological function that extends beyond simple electrostatic engagement with the PM.

INTRODUCTION

Rho family small GTPases are molecular switches that cycle between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. Activation of small GTPases involves guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that promote GDP-for-GTP exchange. Inactivation is enhanced by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which promote the intrinsic GTPase activity (1). Rac1 signaling is further regulated by RhoGDI, which solubilizes cytosolic Rac1-GDP (2, 3). Rho family members drive temporally and spatially organized signaling on the cell plasma membrane (PM) to regulate cell motility, migration, and adhesion (4–7). Among the best characterized Rho GTPases, Rac1 plays a critical role in regulating membrane ruffling, cell adhesion, lamellipodium formation, and macropinocytosis (8–11). Rac1 function is highly compartmentalized to the PM, where it activates the WAVE (WASP family verprolin-homologous) complex that promotes actin dynamics and interacts with key effector proteins, GEFs, and GAPs (12–14).

Rac1 interactions with PM lipids such phosphoinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) have been shown to be critical for Rac1 lateral diffusion, and this observation builds on earlier work suggesting that Rac1 spatial organization and function may be dependent on lipid lateral heterogeneity within the PM (15–17). Recent findings have also shown that Rac1 is organized into large-scale domains at the leading edge of migrating cells that are correlated with Rac1 activation and PIP3 gradients (16). However, details of Rac1 organization on shorter-length scales are unclear. Moreover, the underlying mechanisms that might drive Rac1 organization on the PM are likewise not well defined, including the role of the Rac1 membrane anchor that comprises a geranylgeranylated C-terminal CAAX motif, an additional palmitoyl lipid, and a polybasic domain (PBD) (18–20). Using electron microscopy (EM) combined with nanoscale spatial analysis, we show here that Rac1 forms nanometer-sized domains, termed nanoclusters, that are dependent on guanine nucleotide-binding states. Colocalization analysis further shows that Rac1 nanoclusters are enriched in phosphatidic acid (PA) and PIP3. The capacity for distinct lipid sorting is driven by complex interactions between the Rac1 C-terminal lipid-anchored PBD and PM lipids. Rac1 nanocluster formation and lipid sorting directly correlate with the ability of cells to undergo macropinocytosis.

RESULTS

Rac1 is spatially segregated into nanoclusters on the PM.

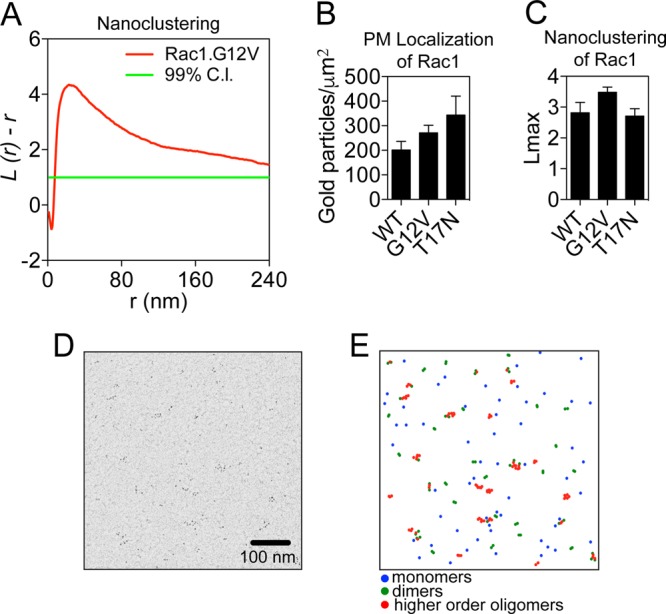

The membrane anchor of Rac1 interacts with the PM and is necessary for its function (21). Furthermore, experiments using single-particle tracking and photoactivated localized microscopy (SPT-PALM) show that Rac1 is recruited to the leading edge of cells, suggesting heterogeneous distribution on the PM (16). To examine Rac1 spatial organization at higher resolution, we used electron microscopy (EM). Intact two-dimensional (2D) PM sheets of baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged wild-type (WT) Rac1 (GFP-Rac1.WT), constitutively GTP-bound oncogenic mutant Rac1.G12V (GFP-Rac1.G12V), or dominant negative mutant Rac1.T17N (GFP-Rac1.T17N) were attached to EM grids and immunolabeled with 4.5-nm gold nanoparticles conjugated directly to anti-GFP antibody. The gold particle distribution on the PM sheets was imaged by transmission EM. The spatial distribution of the gold particles was then quantified using univariate K functions, plotted as L(r) − r (Fig. 1A) as defined in Materials and Methods. Values of L(r) − r above the 99% confidence interval (CI) indicate statistically significant clustering at the length scale r. We used the peak value of L(r) − r, termed Lmax, to summarize the spatial data. The extents of gold labeling for all Rac1 proteins were similar, indicating equal PM localization (Fig. 1B). Our results show that GFP-Rac1.GDP and GFP-Rac1.GTP form nanoclusters on the PM with a diameter of ∼25 nm (Fig. 1A, C, D, and E). The Lmax values for Rac1.GDP and Rac1.GTP were similar to Lmax values observed previously for Ras (22), indicating a similar extent of nanoclustering.

FIG 1.

Rac1 forms nanoclusters on the plasma membrane. (A) Clustering quantification. A plot of the weighted mean standardized univariate K function for GFP-Rac1.G12V is shown. 99% CI, 99% confidence interval for a random pattern. Values for L(r) − r above the confidence interval indicate significant clustering. (B) Intact PM sheets from BHK cells ectopically expressing GFP-Rac1.WT, GFP-Rac1.G12V, or GFP-Rac1.T17N were labeled with anti-GFP coupled to 4.5-nm gold particles and visualized by EM. The number of gold particles per square micrometer quantifies the extent of PM localization and is shown as means ± standard errors of the means (n = 15 to 20 PM sheets). (C) The same PM sheets as described for panel B were analyzed using univariate K functions, and the resulting data were summarized as mean Lmax ± standard error of the mean. (D) Sample EM image (1 μm2) of 4.5-nm gold particles on a PM sheet taken from BHK cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V. (E) Local L(r) mapping (with r = 15 nm) was applied to the image in panel D to identify monomers, dimers, and higher-order oligomers, which were then color-coded as per the legend.

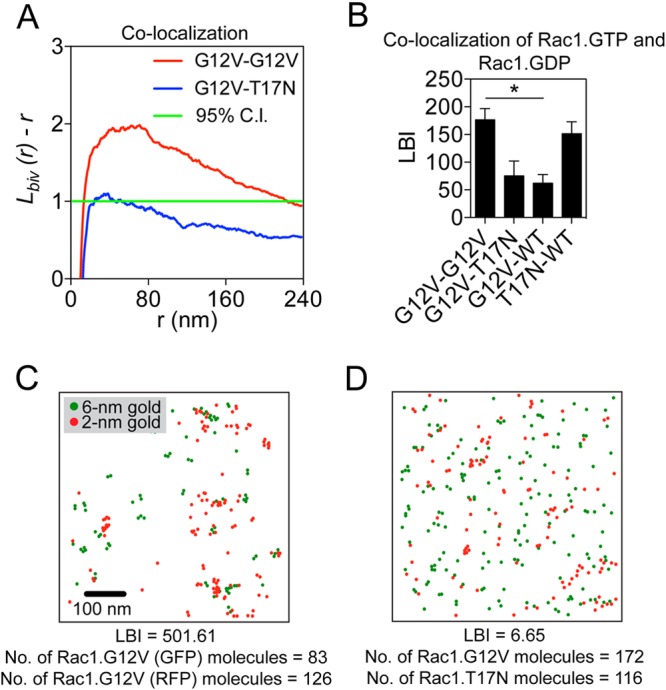

Ras proteins undergo guanine nucleotide-dependent spatial segregation, such that Ras.GDP and Ras.GTP nanoclusters are spatially nonoverlapping (23). To examine whether Rac1 displays similar spatial segregation, we analyzed colocalization between Rac1.GTP and Rac1.GDP. Intact PM sheets of BHK cells coexpressing GFP-Rac1.G12V and red fluorescent protein (RFP)-Rac1.T17N were attached to EM grids and immunogold labeled with 6-nm gold particles conjugated to anti-GFP antibody and 2-nm gold particles conjugated to anti-RFP antibody, respectively. Colocalization between the two populations of the gold particles was quantified using bivariate K functions plotted as Lbiv(r) − r (Fig. 2A). Values of Lbiv(r) − r above the 95% CI indicate statistically significant colocalization. As a summary statistic, we used a defined integration of the Lbiv(r) − r curves, termed Lbiv integrated (LBI) (22). LBI values above 100 indicate significant colocalization, and the greater the LBI value, the more extensive the colocalization between the two gold populations. The LBI value for GFP-Rac1.G12V and RFP-Rac1.G12V was high, consistent with the extensive colocalization of GFP- and RFP-labeled Rac1.GTP molecules (Fig. 2B and C). Similarly GFP-Rac1.WT and RFP-Rac1.T17N showed significant colocalization (Fig. 2B), as evidenced by high LBI values. In contrast, the LBI values for GFP-Rac1.G12V and RFP-Rac1.T17N and for GFP-Rac1.G12V and RFP-Rac1.WT in serum-starved BHK cells were both below 100, indicating efficient spatial segregation between GTP-bound Rac1 and GDP-bound Rac1 (Fig. 2B and D). Taken together, these results show that Rac1 forms spatially segregated nanoclusters in a guanine nucleotide-dependent manner.

FIG 2.

Rac1 nanoclusters are spatially segregated. (A) Quantification of colocalization. Plots of the weighted mean standardized bivariate K functions for GFP-Rac1.G12V/RFP-Rac1.G12V and GFP-Rac1.G12V/RFP-Rac1.T17N. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Values of Lbiv(r) − r above the confidence interval indicate significant coclustering/colocalization between the two populations. Values within the confidence interval indicate no spatial interaction or minimal coclustering between the two populations. (B) PM sheets from BHK cells coexpressing GFP- and RFP-Rac1 constructs were labeled with anti-GFP coupled to 6-nm gold particles and anti-RFP coupled to 2-nm gold particles and visualized by EM. Colocalization of the GFP- and RFP-Rac1 proteins was then analyzed using bivariate K functions, and the resulting data are summarized as LBI values ± standard errors of the means (n = 15 to 20 PM sheets). Statistical significance of differences was determined using bootstrap tests (*, P < 0.001). (C and D) Sample EM images with gold particles color-coded according to size of PM sheets from BHK cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V and RFP-Rac1.G12V (high LBI value) or GFP-Rac1.G12V and RFP-Rac1.T17N (low LBI value).

PA and PIP3 are key structural components of Rac1 nanoclusters.

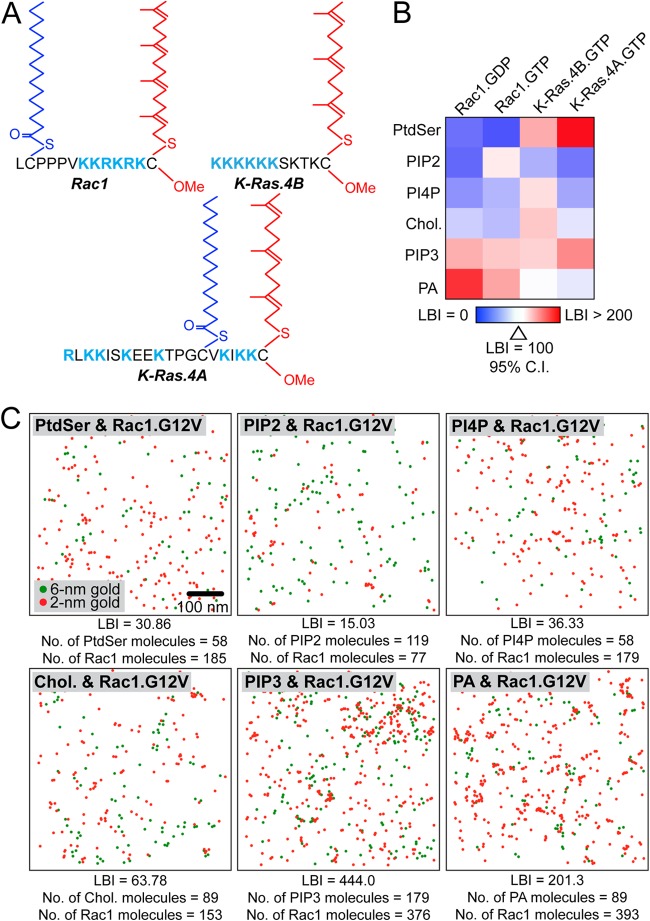

We next used EM colocalization assays to determine the lipid composition of Rac1 nanoclusters. Intact PM sheets of BHK cells coexpressing an RFP-tagged Rac1 construct (Rac1.GTP or Rac1.GDP) and a GFP-tagged lipid probe were attached to EM grids. GFP and RFP were labeled with 6-nm gold particles conjugated to anti-GFP antibody and 2-nm gold particles conjugated to anti-RFP antibody, respectively. LBI values to quantify the extent of colocalization were calculated and arrayed in a heat map (Fig. 3B and C). Since the Rac1 membrane anchor contains elements shared by both K-Ras4A and K-Ras4B, notably, polybasic residues in addition to prenylation and palmitoylation in the case of K-Ras4A (Fig. 3A), we also mapped the lipid compositions of K-Ras4A and K-Ras4B nanoclusters (Fig. 3B). The heat map shows that both Rac1.GDP and Rac1.GTP nanoclusters have a lipid composition that is distinct from that of K-Ras4A and previously characterized K-Ras4B (22). Specifically, Rac1.GDP and Rac1.GTP nanoclusters are enriched in PA and PIP3, as reflected by high LBI values with the PA (GFP-PASS, where PASS is biosensor with superior sensitivity) and PIP3 (GFP-PH-Akt, where PH is the pleckstrin homology domain) lipid probes.

FIG 3.

Rac1 nanoclusters have distinct lipid compositions. (A) Diagram of Rac1, K-Ras4B, and K-Ras4A membrane anchors showing palmitoylation, prenylation, and PBDs. (B) PM sheets from BHK cells coexpressing GFP-lipid binding probes and RFP-Rac1 (G12V or WT) or K-Ras.G12V constructs (K-Ras4A or K-Ras4B) were labeled with anti-GFP antibody coupled to 6-nm gold particles and anti-RFP antibody coupled to 2-nm gold particles and visualized by EM. Colocalization was analyzed using bivariate K functions, and the resulting data are summarized as LBI values ± standard errors of the means (n = 15 to 20 PM sheets). Lipid binding probes: PtdSer, LactC2; phosphoinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2), PH-PLCδ; phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P), FAPP1; cholesterol (chol), D4; PIP3, PH-Akt; PA, PASS. (C) Representative EM images with gold particles color-coded according to the size of PM sheets taken from BHK cells expressing different GFP-lipid binding probes and RFP-Rac1.G12V. The LBI value for each example is shown.

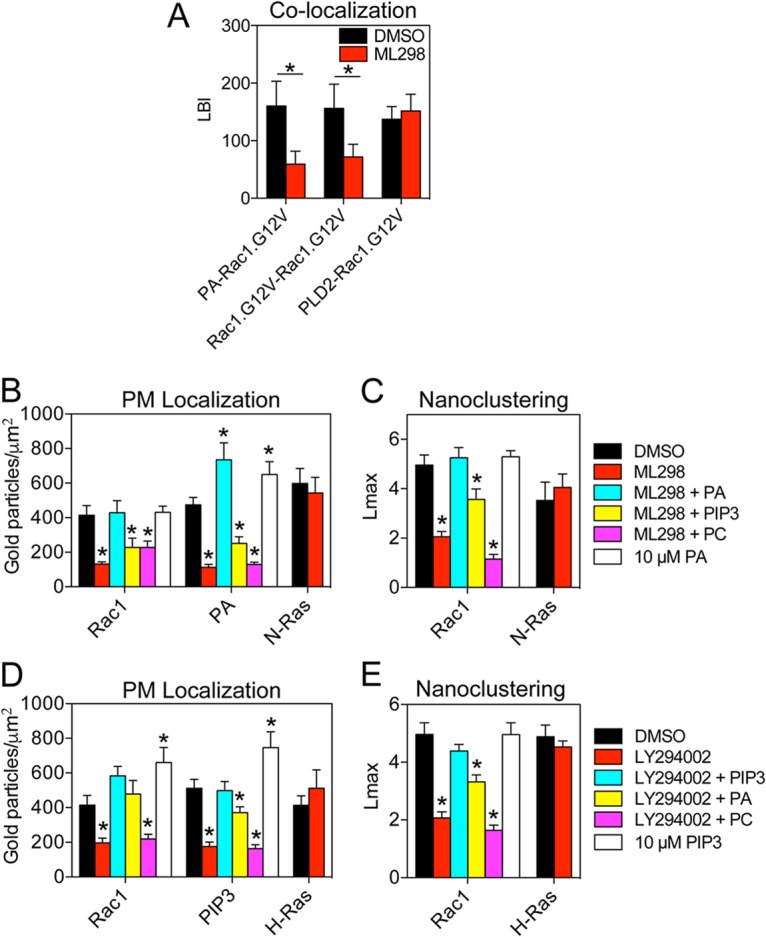

To validate enrichment with PA, we acutely depleted endogenous PA and measured the resulting changes in Rac1 clustering. BHK cells expressing the PA probe (GFP-PASS) were treated for 1 h with 0.5 μM ML298 and analyzed by EM. ML298 is a specific inhibitor of phospholipase D2 (PLD2), which catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylcholine (PC) to PA. Treatment with ML298 significantly decreased the amount of gold labeling of PA, indicating that inhibiting PLD2 effectively depleted endogenous PA in the PM (Fig. 4B). In a parallel EM experiment using BHK cells ectopically expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V, ML298 treatment both significantly mislocalized GFP-Rac1.G12V from the PM and disrupted the nanoclustering of GFP-Rac1.G12V remaining on the PM (Fig. 4B and C). Bivariate EM analysis of the GFP-PA probe and RFP-Rac1.G12V with and without ML298 showed that ML298 treatment significantly reduced the association between the PA probe and Rac1 (Fig. 4A). In contrast, in BHK cells coexpressing GFP-PLD2 and RFP-Rac1, the LBI value for GFP-PLD2 and RFP-Rac1 was not affected by ML298 treatment, indicating that inhibiting the enzymatic activity of PLD2 did not interfere with the spatial colocalization between Rac1 and PLD2 (Fig. 4A). This finding suggests that the disrupted clustering induced by ML298 is a result of PA loss and not mislocalization of PLD2. To further validate PA involvement in Rac1 clustering, BHK cells expressing either GFP-PASS or GFP-Rac1.G12V were treated with ML298 and supplemented with exogenous PA. Exogenous PA effectively rescued the PM localization and nanoclustering of GFP-Rac1.G12V in ML298-treated cells (Fig. 4B and C). PA added to the outer leaflet of the PM is delivered to the inner leaflet because control experiments show that adding supplemental PA to BHK cells significantly enhanced gold labeling of the PA probe on the inner leaflet (Fig. 4B). As a negative control, we found that N-Ras PM localization and clustering were not sensitive to ML298 treatment (Fig. 4B and C).

FIG 4.

Rac1 nanoclusters are structurally dependent on PA and PIP3. (A) LBI values for coclustering between GFP-PA binding probe and RFP-Rac1.G12V, GFP-Rac1.G12V and RFP-Rac1.G12V, and GFP-PLD2 and RFP-Rac1.G12V in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 0.5 μM phospholipase D2 (PLD2)-specific inhibitor ML298 for 1 h. Data are shown as means ± standard errors of the means (n = 10 to 15 PM sheets). Statistical significance of differences between treatments was determined using bootstrap tests (*, P < 0.001). (B) BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1.G12V, PA probe, or N-Ras.G12V were treated for 1 h with 0.5 μM ML298, ML298 plus DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PA, ML298 plus DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PIP3, ML298 plus DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PC, DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PA only, or DMSO and prepared for univariate EM as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The number of gold particles per square micrometer quantifies the extent of PM localization and is shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 15 to 20 PM sheets). Statistical significance of differences between treatments and DMSO for each construct (Rac1, PA, and N-Ras) was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 0.05). (C) The same PM sheets as described for panel B were analyzed using univariate K functions. The data are summarized as mean Lmax ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance of differences between treatments and DMSO for Rac1 and N-Ras was determined using bootstrap tests (*, P < 0.05). (D) BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1.G12V, PIP3 probe, or H-Ras.G12V were treated for 1 h with 15 μM phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002 (LY), LY294002 plus DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PA, LY294002 plus DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PIP3, LY294002 plus DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PC, DMEM supplemented with 10 μM exogenous PIP3 only, or DMSO and prepared for EM as described for panel B. The number of gold particles per square micrometer is shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 12 to 20 PM sheets). Statistical significance of differences between treatments and DMSO for each construct (Rac1, PIP3, and H-Ras) was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 0.05). (E) The same PM sheets as described for panel D were analyzed using univariate K functions. The data are averaged and summarized as mean Lmax ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance of differences between treatments and DMSO for Rac1 and H-Ras was determined using bootstrap tests (*, P < 0.02).

To validate the enrichment of PIP3 in Rac1 nanoclusters, BHK cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V or the PIP3 probe (GFP-PH-Akt) were treated for 1 h with 15 μM LY294002, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, to disrupt the synthesis of PIP3 from 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). LY294002 treatment significantly reduced immunogold labeling of GFP-PH-Akt, indicating effective depletion of PIP3 in the PM (Fig. 4D). LY294002 also effectively mislocalized GFP-Rac1.G12V and disrupted the nanoclustering of Rac1.G12V (Fig. 4D and E). H-Ras nanoclusters do not contain a significant amount of PIP3, and LY294002 had no effect on H-Ras PM localization and clustering (24) (Fig. 4D and E). In lipid add-back experiments, supplementing LY294002-treated cells with exogenous PIP3 effectively rescued the PM localization and clustering of Rac1 (Fig. 4D and E). PIP3 added to the outer leaflet of the PM is delivered to the inner leaflet because control experiments showed that adding supplemental PIP3 to BHK cells significantly enhanced gold labeling of the PIP3 probe on the inner leaflet (Fig. 4D).

To distinguish potential distinct roles of PA and PIP3 in mediating Rac1 clustering, we performed cross-supplementation experiments. As Fig. 4B and C show, adding back exogenous PIP3 in the presence of the PA-depleting ML298 did not rescue the nanoclustering or PM localization of GFP-Rac1.G12V. Further, adding back PA did not rescue the clustering of Rac1 after LY294002 treatment but was able to restore Rac1 to the PM (Fig. 4D and E). These data suggest that PA is sufficient for Rac1 PM localization but that both PA and PIP3 are necessary for nanocluster formation. As an additional control, for lipid specificity we supplemented cells with exogenous phosphatidylcholine (PC). Adding back exogenous PC in the presence of ML298 or LY294002 did not rescue the nanoclustering or PM localization of Rac1.G12V (Fig. 4B to E).

Rac1 polybasic domain encodes specific lipid sorting capacity.

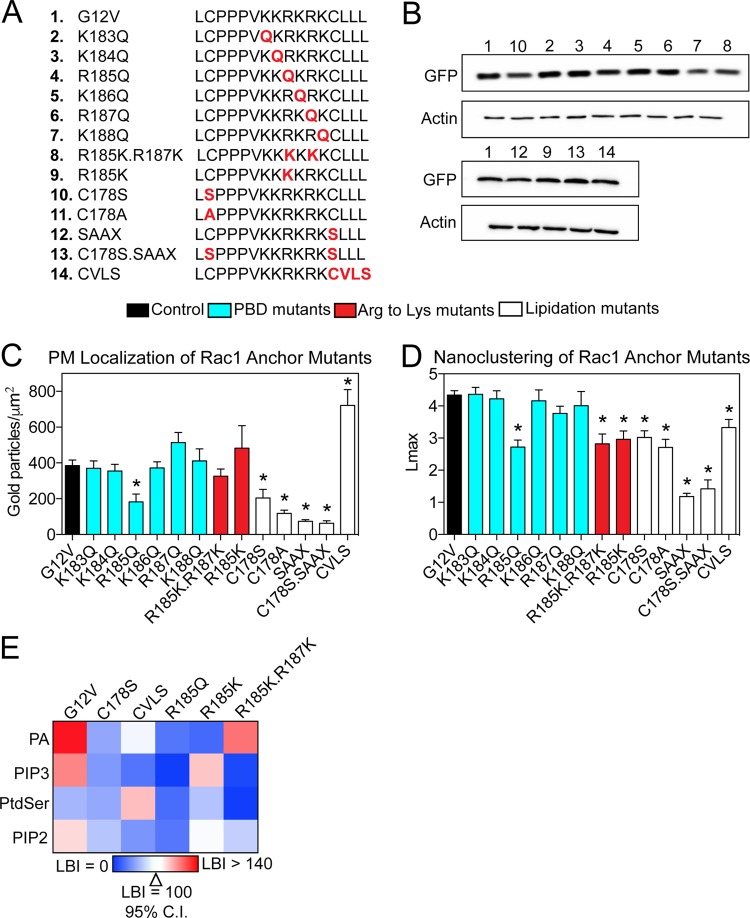

The K-Ras4B membrane anchor containing a farnesylated PBD encodes specificity for PM lipids that extends beyond simple electrostatics (24). This specificity originates in the specific sequence of residues of the K-Ras4B PBD. We hypothesized that the Rac1 membrane anchor, which contains a geranylgeranylated PBD, may also encode lipid binding specificity. We generated a series of point mutations in the Rac1 membrane anchoring domain of GFP-Rac1.G12V (Fig. 5A). Each residue of the PBD (KKRKRK, amino acids 183 to 188) was sequentially mutated to neutral glutamine: GFP-Rac1.G12V.K183Q, GFP-Rac1.G12V.K184Q, GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185Q, GFP-Rac1.G12V.K186Q, GFP-Rac1.G12V.R187Q, and GFP-Rac1.G12V.K188Q. To test the potential difference between arginine and lysine, both arginine residues were mutated to lysines to generate a hexalysine PBD; GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K.R187K, therefore mimics the K-Ras4B PBD. Arg185 was also mutated to lysine to generate GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K. These constructs were equivalently expressed in BHK cells (Fig. 5B). Intact PM sheets of BHK cells ectopically expressing each mutant were then analyzed by EM.

FIG 5.

Mutational analysis of the Rac1 membrane anchor. (A) Table of mutant Rac1 membrane anchor domains. (B) Expression of GFP-tagged Rac1 membrane anchor mutant constructs, with number labels corresponding to mutant number in panel A. Lysates of BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutant constructs were blotted for GFP and actin. (C) PM sheets prepared from BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutants were analyzed by univariate EM as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The number of gold particles per square micrometer quantifies the extent of PM localization and is shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 15 to 20 PM sheets). Statistical significance of differences was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 0.005). (D) The same PM sheets as described for panel C were analyzed using univariate K functions. The data are summarized as mean Lmax ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance of differences was determined using bootstrap tests (*, P < 0.005). (E) PM sheets from BHK cells coexpressing GFP-Rac1 mutant constructs and RFP-lipid binding probes were labeled with anti-GFP antibody coupled to 6-nm gold particles and anti-RFP antibody coupled to 2-nm gold particles and visualized by EM. Colocalization was analyzed using bivariate K functions, and the resulting data were summarized as LBI values ± standard errors of the means (n = 10 to 20 PM sheets). Lipid binding probes: PA, PASS; PIP3, PH-Akt; PtdSer, LactC2; PIP2, PH-PLCδ.

The hexalysine PBD mutant GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K.R187K showed significantly impaired clustering compared to that of the GFP-Rac1.G12V control but did not exhibit diminished PM binding (Fig. 5C and D). Among the single-point PBD mutants, only GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185Q showed impaired clustering compared with that of GFP-Rac1.G12V (Fig. 5D). Mutating other basic residues had no effect on Rac1 nanoclustering or PM binding. GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K also exhibited the same reduction in nanoclustering as the PBD double mutant R185K.R187K. Taken together, the data show that the primary amino acid sequence of the Rac1 PBD determines Rac1 spatial distribution on the PM and highlight Arg185 as a critical residue in the PBD. The data also show that interactions between the Rac1 PBD and the PM are more complex than simple electrostatics.

We used previously described lipid anchor mutants as additional controls (20, 25). GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S and GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178A can no longer be palmitoylated at Cys178, GFP-Rac1.G12V.SAAX can no longer be prenylated, GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S.SAAX eliminates all options for palmitoylation and geranylgeranylation, and GFP-Rac1.G12V.CVLS contains an H-Ras CAAX motif that is farnesylated instead of geranylgeranylated (Fig. 5A). GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S, which can no longer be palmitoylated, was mislocalized from the PM (Fig. 5C). GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178A mimicked this result, suggesting that the mislocalization of Rac1.C178S was not due to potential phosphorylation of the introduced serine residue (Fig. 5C). GFP-Rac1.G12V.SAAX was likewise mislocalized from the PM, due to the loss of prenylation (20, 26). This is supported by GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S.SAAX localization, which showed PM labeling similar to that of Rac1.SAAX (Fig. 5C). In contrast, GFP-Rac1.G12V.CVLS showed an enhancement of PM localization, indicating a potential difference between farnesyl and geranylgeranyl chains (Fig. 5C). These mutants had various effects on Rac1 nanoclustering. Lipidation mutants, including GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S, GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178A, GFP-Rac1.G12V.SAAX, and GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S.SAAX, showed impaired clustering (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, whereas GFP-Rac1.G12V.CVLS showed an increase in PM binding, this farnesylated anchor mutant showed a decrease in clustering (Fig. 5D).

The difference in the clustering of the Rac1 PBD mutants potentially arises from the distinct abilities of different PBD basic residues to associate with PM lipids. To test this, we performed another set of lipid mapping analyses, as shown in Fig. 3. Constructs that had both impaired clustering and PM localization (C178S and R185Q) had impaired association with both PA and PIP3 but no change in association with PIP2 or phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, Rac1.G12V.CVLS showed impaired colocalization with PA and PIP3 but enhanced association with PtdSer (Fig. 5E). Rac1.G12V.R185K showed impaired PA association but maintained PIP3 association, whereas Rac1.G12V.R185K.R187K had impaired PIP3 association but maintained localization with PA (Fig. 5E). Taking these results together, we conclude that the Rac1 PBD sequence encodes lipid binding specificity for PA and PIP3, which is critical for PM binding and spatial organization.

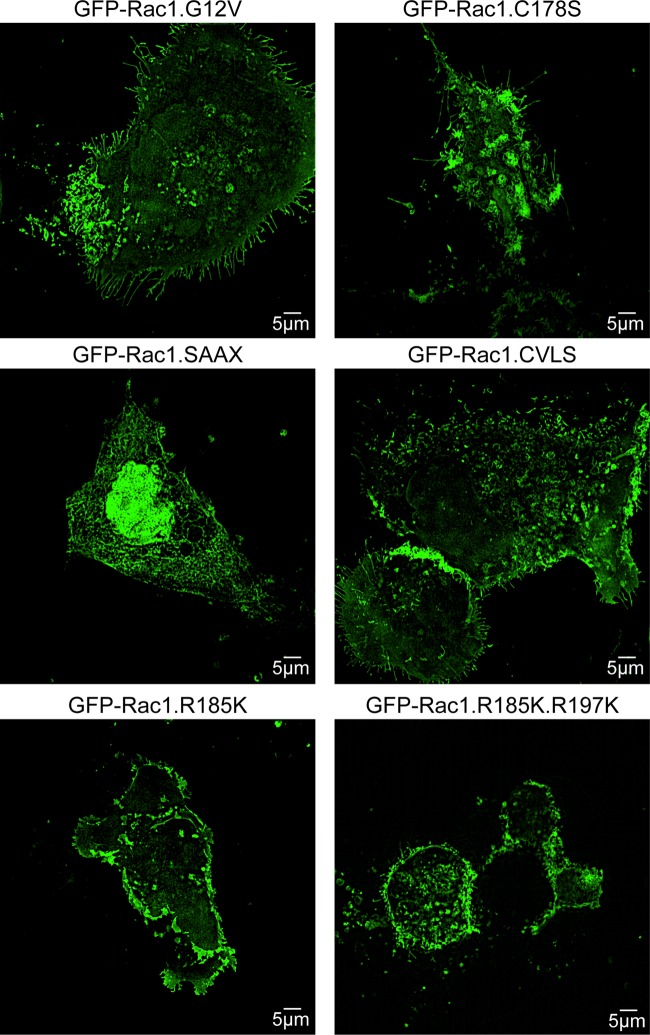

To visualize the distribution of these Rac1 membrane anchor mutants in whole cells, we used superresolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V, GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S, GFP-Rac1.G12V.SAAX, GFP-Rac1.G12V.CVLS, GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K, and GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K.R187K were fixed and visualized by SIM (Fig. 6). Cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V.SAAX were smaller and more elongated, demonstrating predominantly nuclear localization of the protein, consistent with findings of previous studies (27). Cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V and GFP-Rac1.G12V.CVLS were generally larger, with slender filopodium-like protrusions (Fig. 6). Cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S, GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K, and GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K.R187K were smaller with fewer filopodia. However, consistent with the EM, both Rac1.G12V.R185K and Rac1.G12V.R185K.R187K exhibited high levels of PM expression in the SIM images (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Subcellular localization of selected Rac1 anchor mutants. MDCK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutant constructs were fixed and visualized in a Nikon N-SIM confocal microscope with 3D reconstruction. Representative images are shown.

Rac1 nanocluster formation correlates with macropinocytic uptake and cell spreading.

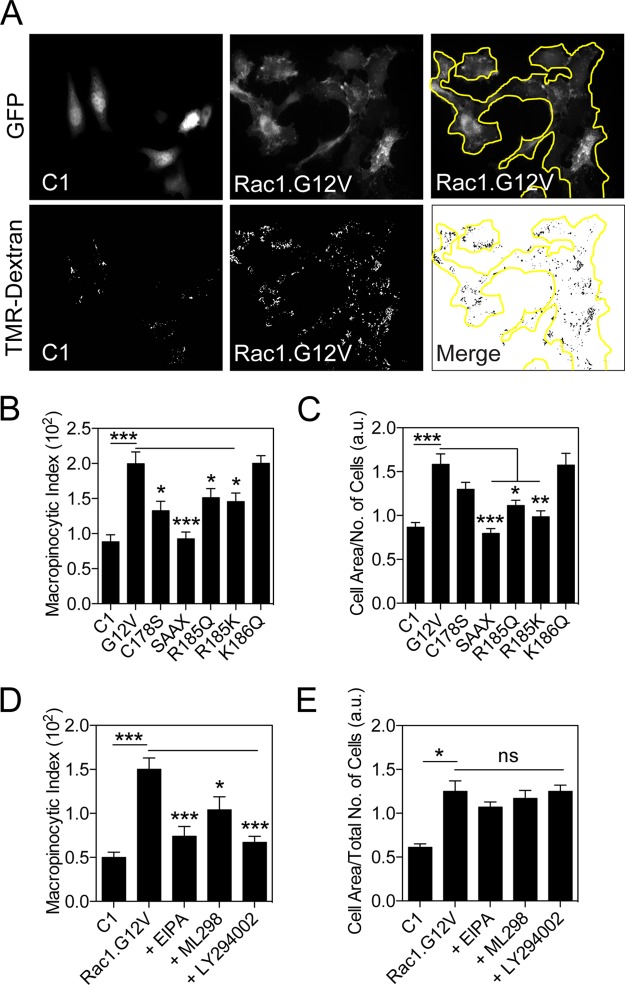

Rac1 plays a critical role in actin filament formation, membrane ruffling, and macropinocytosis (9, 28–30). To examine if Rac1 clustering is functionally relevant, we measured the macropinocytic index of BHK cells. Live BHK cells expressing GFP (control), GFP-tagged Rac1.G12V, Rac1.G12V.C178S, Rac1.G12V.SAAX, Rac1.G12V.R185Q, Rac1.G12V.R185K, or Rac1.G12V.K186Q were serum starved and then incubated with tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-conjugated dextran for 30 min before fixation (Fig. 7A). The amount of dextran incorporation was quantified using wide-field fluorescence microscopy and represented as the macropinocytic index (31). BHK cells yielded a macropinocytic index of 0.88 ± 0.10 (Fig. 7B). Expression of GFP-Rac1.G12V markedly increased the macropinocytic index to 2.00 ± 0.17. The lipidation mutants GFP-Rac1.G12V.C178S and GFP-Rac1.G12V.SAAX and the PBD mutant GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185Q or GFP-Rac1.G12V.R185K all yielded significantly lower macropinocytic index values than cells expressing GFP-Rac1.G12V with a wild-type PBD. Expression of GFP-Rac1.G12V.K186Q did not alter the macropinocytic index.

FIG 7.

Mutation of specific residues in the Rac1 membrane anchor impairs macropinocytosis and cell spreading. (A) Representative sample images of BHK cells expressing GFP-Rac1 mutants and dextran-containing macropinosomes. BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutant constructs or GFP-pC1 (C1; empty vector) were serum starved overnight, treated with medium containing tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-conjugated dextran, and fixed. The total area of dextran-containing macropinosomes in BHK cells expressing GFP-Rac1 mutant constructs or pC1 was divided by cell area (×100), giving the macropinocytic index. (B) Summary of macropinocytosis results, shown as means ± standard errors of the means. Data were averaged from three separate experiments and 200 to 300 cells per condition. Statistical significance of differences was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 0.02; ***, P < 1 × 10−6). (C) Cell area from the experiment shown in panel B was divided by the number of cells per field, giving an average estimate for cell spreading. Data are shown as means ± standard error of the means. Statistical significance of differences was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 1 × 10−4, ***, P < 1 × 10−6). (D) Summary of macropinocytosis results from BHK cells expressing GFP or GFP-Rac1.G12V with or without treatment with EIPA, ML298, or LY294002, shown as means ± standard errors of the means. Data were averaged from three separate experiments and 200 to 300 cells per condition. Statistical significance of differences was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 0.02; ***, P < 5 × 10−5). (E) Cell area from the experiment shown in panel D was divided by the number of cells per field, giving an average estimate for cell spreading. Data are shown as means ± standard errors of the means. Statistical significance of differences was determined using Student's t tests (*, P < 3 × 10−6; ns, not significant).

Since Rac1 also drives cell spreading, we calculated the average surface area of BHK cells ectopically expressing various Rac1 mutants (32). Rac1.G12V markedly increased the surface area of BHK cells; emulating the macropinocytosis results, each PBD mutant that compromised nanoclustering also compromised the ability to induce cell spreading (Fig. 7C). Thus, each mutant with impaired clustering exhibited a reduced capacity to promote macropinocytosis and cell spreading. These data therefore suggest that Rac1 nanoclustering is required for Rac1 function. To further test this conclusion, we examined the functional outcome of reducing Rac1 nanoclustering by decreasing PM PIP3 and PA levels. We pretreated cells with PA-depleting ML298 and PIP3-depleting LY294002 for 30 min and incubated the treated cells with TMR-dextran for 30 min in the presence of the inhibitors. Consistent with results of the previous assay, expression of GFP-Rac1.G12V significantly increased the macropinocytic index and cell area compared to levels in control BHK cells expressing GFP (Fig. 7D and E). Treatment with ML298 and LY294002 significantly attenuated macropinocytosis in GFP-Rac1.G12V-expressing cells as effectively as 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA), a known macropinocytosis inhibitor (Fig. 7D) (31). Interestingly, EIPA, ML298, and LY294002 had no effect on cell spreading, unlike the membrane anchor mutants which also compromised nanoclustering (Fig. 7E). This is not unexpected since inhibitor treatment was only for 30 min, sufficient time to acutely change vesicular trafficking events but likely not long enough to reorganize the actin cytoskeleton and perturb cell adhesion.

DISCUSSION

Our study systematically examines the propensity of Rac1 to form lipid-dependent, spatially segregated nanoclusters on the PM and the biological relevance of Rac1 nanocluster formation. We observed using EM that Rac1 forms nanoclusters, which have a distinct lipid composition, selectively associating with PA and PIP3 over PtdSer, PIP2, other anionic phospholipids, and cholesterol. This capacity to interact with PA and PIP3 is biologically relevant because depleting PM PA or PIP3 decreased Rac1 PM binding and reduced the nanoclustering of the Rac1 protein remaining on the PM. Rac1 nanoclusters are therefore structurally dependent on PA and PIP3, with lipid add-back experiments further indicating that both PA and PIP3 are necessary but not individually sufficient for nanocluster formation.

Rac1 molecules diffusing laterally on the PM can be separated into two populations with fast and very slow diffusion rates (15). It is tempting to speculate that this dynamic behavior may reflect Rac1 proteins that are freely diffusing as monomers and Rac1 proteins confined to nanoclusters. A similar integration of EM spatial mapping data with single-particle tracking data also suggests that Ras proteins may be transiently confined in immobile nanoclusters or diffuse freely (33, 34). One important question is how these findings relate to Rac1 nanoclusters visualized by superresolution light microscopy, which shows that Rac1 nanoclusters have diameters of approximately 200 nm and contain up to 50 proteins (16). In contrast, the EM estimate of Rac1 nanocluster diameter is closer to 25 nm, and the Lmax values observed imply a stoichiometry of closer to five Rac1 proteins per cluster, predicated on the assumption that the clustering behavior of Rac1 broadly emulates that previously described for Ras (35). An interesting possibility is that these smaller Rac1 nanoclusters are collected into larger, more stable assemblies of active Rac1 when confined by membrane ruffles. The formation of these larger assemblies could also be driven by, and indeed be dependent on, localized generation of PIP3 (16), which we show here is a critical structural component of the smaller Rac1 nanocluster.

We also observed that Rac1.GTP nanoclusters are spatially segregated from Rac1.GDP nanoclusters. In this regard, Rac1 is similar to Ras, which forms isoform-specific nanoclusters that are likewise guanine-nucleotide dependent (35, 36). GTP-dependent segregation of Ras proteins is linked to differential orientations, and, hence, contacts of the G domain with the PM in different activation states that in turn modify anchor interactions and promote or inhibit dimerization (37–39). It seems probable that similar core mechanisms may operate for Rac1 although this remains to be formally tested. However, an additional mechanism may involve RhoGDI. A large fraction of Rac1 is complexed with RhoGDI in the cytosol. The mechanisms whereby Rac1 is released from RhoGDI at the PM are complex, but previous work suggests a role for anionic phospholipids such as PIP3 (40), which we have shown here is also required for Rac1 PM binding and spatial organization. Taken together, these results suggest the intriguing possibility that the enrichment of PIP3 in Rac1 nanoclusters generates transient lipid-based domains that serve as sites for further Rac1 delivery to the PM.

Several lines of data indicate that PA and PIP3 anionic lipid specificity is encoded in the Rac1 C-terminal membrane anchor. Mutating arginine to lysine in the PBD, while maintaining the same net positive charge of the PBD, generates nanoclusters with a different lipid composition than that of Rac1 with a wild-type PBD (KKRKRK). For example, R185K showed reduced PA association while R185K.R187K lost PIP3 association. The R185Q mutant displayed a reduction in both PA and PIP3 sorting, suggesting that Arg185 plays a critical role in defining Rac1 PM lipid interactions. Switching the prenyl group from geranylgeranyl to farnesyl also changed Rac1 lipid composition, promoting selective association with PtdSer rather than PA or PIP3. Likewise, losing palmitoyl from the membrane anchor reduced selectivity for PA and PIP3, signifying that both the prenyl and palmitoyl chains are important for membrane affinity. These results suggest that Rac1 interactions with membrane lipids are not simply governed by electrostatics. Rather, the membrane anchor of Rac1 comprises a prenyl-PBD code, in which the basic residues, arginine and lysine, are nonequivalent, and the length of the prenyl chain modifies the lipid binding specificity of the core PBD. This is similar to K-Ras4B, where specificity for PtdSer is encoded in a polylysine-farnesyl membrane anchor (24), which is, in turn, realized by distinct conformational structural dynamics of the anchor that give preference to interactions with PtdSer head groups (24). Similarly, the ADP ribosylation factor (Arf) GEF Brag2 exhibits anionic lipid binding specificity for PIP2 through a polybasic domain that adopts defined conformational orientations (41, 42). We speculate that the Rac1 anchor also adopts a defined structure or structures on the PM that result in selective interactions of side chains on the specific sequence of lysines and arginines in the PBD with PA and PIP3 anionic lipid head groups. In this context, we would speculate that Rac2, an isoform that is expressed only hematopoietic cells and which has a very different membrane anchor (43), will exhibit a different lipid binding specificity from that of Rac1, which may be relevant to its tissue-specific function.

Each Rac1 membrane anchor mutant exhibited different extents of PM localization and nanoclustering, resulting in nanoclusters with different lipid compositions, reflecting distinct lipid binding specificities. The combined effect of these changes was reduced macropinocytosis and cell spreading compared to levels for Rac1.G12V, indicating a critical role for anchor lipid binding specificity in governing effector recruitment and Rac1 signal output. Dissecting the relative importance of spatial organization and PM localization to Rac1 function is more difficult. Loss of palmitate or geranylgeranyl from the anchor or the mutation R185→Q reduced both PM localization and nanoclustering and resulted in decreased macropinocytosis and cell spreading. In contrast the mutation R185→K had no effect on PM localization but diminished clustering and still impaired signal output. These results implicate nanocluster formation and lipid sorting as necessary steps for efficient downstream signaling.

Other studies have also linked PM lipids to Rac1 function. For example, PA is required for membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis through recruitment of the Rac1 GEF T-lymphoma invasion and metastasis-inducing protein 1 (Tiam1) to the PM (44). Similarly, PIP3 is required for the activation of the Rac1 GEF PIP3-dependent Rac1 exchanger (P-Rex1) and is correlated with localized Rac1 activation in the leading edge of migrating cells (15, 16, 45). The results presented here yield new mechanistic insight into this biology by demonstrating that the Rac1 anchor encodes binding specificity for PA and PIP3, which results in the formation of nanoclusters enriched in these anionic lipids. Taken together, these studies suggest that Rac1 nanoclusters act as lipid-based signaling platforms for efficient effector binding and recruitment emulating the spatiotemporal organization of Ras proteins (39, 46, 47). More broadly, the results show that the PBD-prenyl anchors of small GTPases such as K-Ras and Rac1 are nonequivalent and have biological functions that extend beyond simple electrostatic engagement with the PM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Rac1 membrane anchor mutant constructs were generated using a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) and PCR, using GFP-Rac1.G12V as the parent vector (30). The mutant constructs contained both a G12V activating mutation and respective membrane anchor mutation(s). Sergio Grinstein (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada) provided GFP-LactC2, and Guangwei Du (University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX) provided GFP-PASS, GFP-pleckstrin homology domain (PH)-phospholipase Cδ (PLCδ), and GFP-PH-Akt. Tamas Balla (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD) provided GFP-FAPP1.

Cell culture and transfection.

Wild-type BHK cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% bovine calf serum (BCS) or in DMEM under serum-starved conditions where noted. BHK cells were transfected 24 h after plating using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) reagent and fixed 24 h posttransfection. Wild-type MDCK cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MDCK cells were transfected 24 h after plating using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) reagent and fixed 24 h posttransfection. PIP3 levels were manipulated by treating cells for 1 h with 15 μM PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Sigma-Aldrich). PIP3 levels were elevated with 10 μM exogenous 18:0 to 20:4 PIP3 (Avanti Polar Lipids). PA levels were manipulated using 0.5 μM phospholipase D2 (PLD2)-specific inhibitor ML298 (Sigma-Aldrich). PA levels were elevated with 10 μM exogenous egg PA (Avanti Polar Lipids). PC levels were elevated with 10 μM exogenous PC (Avanti Polar Lipids).

Western blotting.

BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutant constructs were grown to confluence and harvested. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by a 5-min incubation in 100 μl of lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 25 mM NaF, 75 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 3 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min. The concentration of total protein was measured and taken from the supernatant. Twenty micrograms of total protein was mixed with sample buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 20 mg/ml SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mg/ml bromophenol blue dye, and 15.4 mg/ml DTT), denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and resolved by electrophoresis in a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were electro-transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using prechilled transfer buffer (3.6 mg/ml glycine, 7.25 mg/ml Tris base, 0.46 mg/ml SDS, 20% methanol). PVDF membranes were rinsed three times with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and blocked for 1 h in 5% skim milk in TBST. Primary antibody labeling was performed overnight by inoculating the PVDF membrane in blocking solution containing primary antibody with anti-GFP at a 1:3,000 dilution and antiactin at 1:1,000. PVDF membranes were washed three times in TBST and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody in blocking solution (anti-rabbit antibody at 1:2,000; anti-mouse antibody at 1:8,000). PVDF membranes were washed three times with TBST again and incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) solution consisting of 2 ml of SuperSignal West Pico stable peroxide solution and 2 ml of SuperSignal West Dura stable peroxide solution.

Electron microscopy and spatial mapping to quantify the extent of nanoclustering and coclustering on the plasma membrane. (i) Univariate K function analysis: spatial distribution for single species.

Univariate EM quantifies the clustering of a single population on the inner leaflet of the cell plasma membrane and has been described previously (22, 24, 35). BHK cells transiently transfected with a GFP-tagged protein were grown to ∼75% confluence. Intact apical PM sheets were attached to copper EM grids, washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde, immunolabeled with 4.5-nm gold particles conjugated to anti-GFP antibody, and stained with uranyl acetate. Digital images of the intact PM sheets were obtained using a Jeol JEM-1400 transmission EM at a magnification of ×100,000. From these images, 1-μm2 regions were selected, and each gold particle in the region was assigned x and y coordinates using ImageJ. The gold particle distribution and extent of nanoclustering were calculated using Ripley's K function, as shown in the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

whereby K(r) is the univariate K function for a pattern of n points in area A, r is the radius at which K(r) is calculated (length scale = 1 < r < 240 nm at 1-nm increments), ∣∣xi − xj∣∣ is Euclidean distance, 1(∣∣xi − xj∣∣ ≤ r) is the indicator function with a value of 1 if ∣∣xi − xj∣∣ ≤ r and a value of 0 otherwise, and wij−1 is the proportion of the circumference of the circle with center xi and radius ∣∣xi − xj∣∣ contained within A. L(r) − r is a linear transformation of K(r) and standardized on the 99% confidence interval (CI) estimated from Monte Carlo simulations. Under the null hypothesis of complete spatial randomness, L(r) − r has an expected value of 0 for all values of r. Positive deviations of the function from the confidence interval indicate significant clustering. For each condition in this study, 10 to 20 PM sheets were collected and analyzed. Bootstrap tests were used to determine statistical differences between replicated point patterns, and significance was evaluated against 1,000 bootstrap samples (24, 48).

(ii) Bivariate K function analysis: coclustering between two species.

The coclustering technique quantifies coclustering of two populations of gold-labeled proteins or lipids on the inner leaflet of the cell plasma membrane (22, 24, 35). Intact apical PM sheets prepared from BHK cells transiently expressing GFP-tagged and RFP-tagged proteins were attached to copper EM grids, fixed, and labeled with 2-nm gold particles directly conjugated to anti-RFP antibody and 6-nm gold particles conjugated directly to anti-GFP antibody (22, 24, 35). Digital images of the intact PM sheets were obtained using a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission EM at a magnification of ×100,000. From these images, 1-μm2 regions were selected, and each gold particle in the region was assigned x and y coordinates using ImageJ. The gold particle distribution was analyzed using a bivariate K function that calculates coclustering of the two different gold particle populations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where Kbiv(r) is the weighted mean of two bivariate K functions. Kbs(r) characterizes the distribution of large (b, big; 6-nm) gold particles with respect to each small (s) gold particle and Ksb(r) characterizes the distribution of small (2-nm) gold particles with respect to each large gold particle. Area A contains nb large gold particles and ns small gold particles. Remaining notations are the same as for equations 1 and 2. Lbiv(r) − r is a linear transformation of Kbiv(r) and is standardized on a 95% CI derived from 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations. Under the null hypothesis of no spatial interaction between the two gold populations, Lbiv(r) − r has an expected value of 0 for all values of r. Positive deviations of Lbiv(r) − r from the CI indicate significant coclustering between the two gold populations. A useful numeric summary statistic to quantify the extent of coclustering is the area under the Lbiv(r) − r curve over the range 10 < r < 110 nm, which is termed Lbiv(r) − r integrated, or LBI, defined as follows:

| (7) |

For each condition, 10 to 20 PM sheets were imaged, analyzed, and averaged. Standardized (Std) LBI values of >100 (95% CI) indicate significant coclustering. Statistical significance of differences between replicated bivariate point patterns was determined using bootstrap tests (24, 48).

(iii) Local L(r) mapping of spatial point patterns.

Equations 1 and 2 were used to calculate the L(r) value for each gold particle in representative gold point patterns at an r of 15 nm. Each particle was then color-coded according to its L(r) value. This use of the L(r) function allows objective identification and visualization of monomers, dimers, and higher-order oligomers in a gold point pattern.

SIM.

MDCK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutant constructs were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were visualized using a Nikon N-SIM superresolution microscope equipped with a 100× (1.49 numerical aperture [NA]) CFI Apo TIRF oil objective lens and Hamamatsu ORCA-Flash, version 4.0, V2 digital camera. Images were slice reconstructed via three-dimensional structured illuminated microscopy (3D-SIM) using the manufacturer's software.

Macropinocytosis and cell spreading.

The quantification of macropinocytosis was performed as described previously (31). BHK cells expressing GFP-tagged Rac1 mutant constructs or GFP-pC1 (empty vector) were serum starved overnight, treated with medium plus 1 mg/ml 70-kDa tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-conjugated dextran for 30 min, washed with PBS, and subsequently fixed. Approximately 10 to 20 fields per sample were taken on a Zeiss Axiovert inverted 200M wide-field microscope equipped with a 63× (1.4 NA) phase objective lens and charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera. Using ImageJ, the total area of macropinosomes was divided by total cell area (×100), giving the macropinocytic index as an indicator of dextran uptake and macropinocytosis. Data were averaged from three separate experiments and approximately 250 cells. Using the same data obtained from macropinocytosis quantification, cell area was divided by the number of cells as an indicator of cell spreading (32).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the NIH (R01 GM124233). K.N.M. was also supported by The Rosalie B. Hite Graduate Fellowship in Cancer Research at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. 2007. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell 129:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bustelo XR, Ojeda V, Barreira M, Sauzeau V, Castro-Castro A. 2011. Rac-ing to the plasma membrane. Small GTPases 3:60–66. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.19111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosser YQ, Nomanbhoy TK, Aghazadeh B, Manor D, Combs C, Cerione RA, Rosen MK. 1997. C-terminal binding domain of Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor directs N-terminal inhibitory peptide to GTPases. Nature 387:814–819. doi: 10.1038/42961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall A. 1998. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science 279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson CD, Ridley AJ. 2018. Rho GTPase signaling complexes in cell migration and invasion. J Cell Biol 217:447–457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridley AJ. 2001. Rho GTPases and cell migration. J Cell Sci 114:2713–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nobes CD, Hall A. 1999. Rho GTPases control polarity, protrusion, and adhesion during cell movement. J Cell Biol 144:1235–1244. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustelo XR, Sauzeau V, Berenjeno IM. 2007. GTP-binding proteins of the Rho/Rac family: regulation, effectors and functions in vivo. Bioessays 29:356–370. doi: 10.1002/bies.20558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egami Y, Taguchi T, Maekawa M, Arai H, Araki N. 2014. Small GTPases and phosphoinositides in the regulatory mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation. Front Physiol 5:374. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibata AC, Chen LH, Nagai R, Ishidate F, Chadda R, Miwa Y, Naruse K, Shirai YM, Fujiwara TK, Kusumi A. 2013. Rac1 recruitment to the archipelago structure of the focal adhesion through the fluid membrane as revealed by single-molecule analysis. Cytoskeleton 70:161–177. doi: 10.1002/cm.21097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choma DP, Pumiglia K, DiPersio CM. 2004. Integrin α3β1 directs the stabilization of a polarized lamellipodium in epithelial cells through activation of Rac1. J Cell Sci 117:3947–3959. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wertheimer E, Gutierrez-Uzquiza A, Rosemblit C, Lopez-Haber C, Sosa MS, Kazanietz MG. 2012. Rac signaling in breast cancer: a tale of GEFs and GAPs. Cell Signal 24:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen B, Chou HT, Brautigam CA, Xing W, Yang S, Henry L, Doolittle LK, Walz T, Rosen MK. 2017. Rac1 GTPase activates the WAVE regulatory complex through two distinct binding sites. Elife 6:e29795. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch HC, Coadwell WJ, Ellson CD, Ferguson GJ, Andrews SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempest P, Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. 2002. P-Rex1, a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 - and Gβγ-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac. Cell 108:809–821. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das S, Yin T, Yang Q, Zhang J, Wu YI, Yu J. 2015. Single-molecule tracking of small GTPase Rac1 uncovers spatial regulation of membrane translocation and mechanism for polarized signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E267–E276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409667112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remorino A, De Beco S, Cayrac F, Di Federico F, Cornilleau G, Gautreau A, Parrini M, Masson J, Dahan Coppey M. 2017. Gradients of Rac1 nanoclusters support spatial patterns of Rac1 signaling. Cell Reports 21:1922–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moissoglu K, Kiessling V, Wan C, Hoffmann BD, Norabuena A, Tamm LK, Schwartz MA. 2014. Regulation of Rac1 translocation and activation by membrane domains and their boundaries. J Cell Sci 127:2565–2576. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ten Klooster JP, Jaffer ZM, Chernoff J, Hordijk PL. 2006. Targeting and activation of Rac1 are mediated by the exchange factor beta-Pix. J Cell Biol 172:759–769. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Hennik PB, ten Klooster JP, Halstead JR, Voermans C, Anthony EC, Divecha N, Hordijk PL. 2003. The C-terminal domain of Rac1 contains two motifs that control targeting and signaling specificity. J Biol Chem 278:39166–39175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarro-Lerida I, Sanchez-Perales S, Calvo M, Rentero C, Zheng Y, Enrich C, Del Pozo MA. 2012. A palmitoylation switch mechanism regulates Rac1 function and membrane organization. EMBO J 31:534–551. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam BD, Hordijk PL. 2013. The Rac1 hypervariable region in targeting and signaling: a tail of many stories. Small GTPases 4:78–89. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.23310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Liang H, Rodkey T, Ariotti N, Parton RG, Hancock JF. 2014. Signal integration by lipid-mediated spatial cross talk between Ras nanoclusters. Mol Cell Biol 34:862–876. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01227-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abankwa D, Gorfe AA, Hancock JF. 2007. Ras nanoclusters: molecular structure and assembly. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Prakash P, Liang H, Cho KJ, Gorfe AA, Hancock JF. 2017. Lipid-sorting specificity encoded in K-Ras membrane anchor regulates signal output. Cell 168:239–251.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce PL, Cox AD. 2003. Rac1 and Rac3 are targets for geranylgeranyltransferase I inhibitor-mediated inhibition of signaling, transformation, and membrane ruffling. Cancer Res 63:7959–7967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choy E, Chiu VK, Silletti J, Feoktistov M, Morimoto T, Michaelson D, Ivanov IE, Philips MR. 1999. Endomembrane trafficking of ras: the CAAX motif targets proteins to the ER and Golgi. Cell 98:69–80. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaelson D, Abidi W, Guardavaccaro D, Zhou M, Ahearn I, Pagano M, Philips MR. 2008. Rac1 accumulates in the nucleus during the G2 phase of the cell cycle and promotes cell division. J Cell Biol 181:485–496. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida S, Hoppe AD, Araki N, Swanson JA. 2009. Sequential signaling in plasma-membrane domains during macropinosome formation in macrophages. J Cell Sci 122:3250–3261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckley CM, King JS. 2017. Drinking problems: mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation. FEBS J 284:3778–3790. doi: 10.1111/febs.14115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. 1992. The small GTP-binding protein Rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Commisso C, Flinn RJ, Bar-Sagi D. 2014. Determining the macropinocytic index of cells through a quantitative image-based assay. Nat Protoc 9:182–192. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wurtzel JG, Kumar P, Goldfinger LE. 2012. Palmitoylation regulates vesicular trafficking of R-Ras to membrane ruffles and effects on ruffling and cell spreading. Small GTPases 3:139–153. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.21084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hancock JF, Parton RG. 2005. Ras plasma membrane signalling platforms. Biochem J 389:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakoshi H, Iino R, Kobayashi T, Fujiwara T, Ohshima C, Yoshimura A, Kusumi A. 2004. Single-molecule imaging analysis of Ras activation in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:7317–7322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prior IA, Muncke C, Parton RG, Hancock JF. 2003. Direct visualization of Ras proteins in spatially distinct cell surface microdomains. J Cell Biol 160:165–170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plowman SJ, Muncke C, Parton RG, Hancock JF. 2005. H-ras, K-ras, and inner plasma membrane raft proteins operate in nanoclusters with differential dependence on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:15500–15505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504114102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prakash P, Zhou Y, Liang H, Hancock JF, Gorfe AA. 2016. Oncogenic K-Ras binds to an anionic membrane in two distinct orientations: a molecular dynamics analysis. Biophys J 110:1125–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abankwa D, Hanzal-Bayer M, Ariotti N, Plowman SJ, Gorfe AA, Parton RG, McCammon JA, Hancock JF. 2008. A novel switch region regulates H-ras membrane orientation and signal output. EMBO J 27:727–735. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Y, Hancock JF. 2015. Ras nanoclusters: Versatile lipid-based signaling platforms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ugolev Y, Berdichevsky Y, Weinbaum C, Pick E. 2008. Dissociation of Rac1(GDP)·RhoGDI complexes by the cooperative action of anionic liposomes containing phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and GTP. J Biol Chem 283:22257–22271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, Hancock JF. 2017. Lipid sorting and the activity of Arf signaling complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:11266–11267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715502114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karandur D, Nawrotek A, Kuriyan J, Cherfils J. 2017. Multiple interactions between an Arf/GEF complex and charged lipids determine activation kinetics on the membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:11416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707970114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamauchi A, Marchal CC, Molitoris J, Pech N, Knaus U, Towe J, Atkinson SJ, Dinauer MC. 2005. Rac GTPase isoform-specific regulation of NADPH oxidase and chemotaxis in murine neutrophils in vivo. J Biol Chem 280:953–964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohdanowicz M, Schlam D, Hermansson M, Rizzuti D, Fairn GD, Ueyama T, Somerharju P, Du G, Grinstein S. 2013. Phosphatidic acid is required for the constitutive ruffling and macropinocytosis of phagocytes. Mol Biol Cell 24:1700–1712. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e12-11-0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiner OD. 2002. Rac activation: P-Rex1—a convergence point for PIP3 and Gβγ? Curr Biol 12:R429. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00917-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Y, Hancock JF. 2018. Deciphering lipid codes: K-Ras as a paradigm. Traffic 19:157–165. doi: 10.1111/tra.12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y, Prakash P, Gorfe AA, Hancock JF. 11 December 2017. Ras and the plasma membrane: a complicated relationship. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plowman SJ, Hancock JF. 2005. Ras signaling from plasma membrane and endomembrane microdomains. Biochim Biophys Acta 1746:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]