Abstract

Background

Sepsis remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, leading to the implementation of the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1). SEP-1 identifies patients with “severe sepsis” via clinical and laboratory criteria and mandates interventions, including lactate draws and antibiotics, within a specific time window. We sought to characterize the patients affected and to study the implications of SEP-1 on patient care and outcomes.

Methods

All adults admitted to the University of Chicago from November 2008 to January 2016 were eligible. Modified SEP-1 criteria were used to identify appropriate patients. Time to lactate draw and antibiotic and IV fluid administration were calculated. In-hospital mortality was examined.

Results

Lactates were measured within the mandated window 32% of the time on the ward (n = 505) compared with 55% (n = 818) in the ICU and 79% (n = 2,144) in the ED. Patients with delayed lactate measurements demonstrated the highest in-hospital mortality at 29%, with increased time to antibiotic administration (median time, 3.9 vs 2.0 h). Patients with initial lactates > 2.0 mmol/L demonstrated an increase in the odds of death with hourly delay in lactate measurement (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.0003-1.05; P = .04).

Conclusions

Delays in lactate measurement are associated with delayed antibiotics and increased mortality in patients with initial intermediate or elevated lactate levels. Systematic early lactate measurement for all patients with sepsis will lead to a significant increase in lactate draws that may prompt more rapid physician intervention for patients with abnormal initial values.

Key Words: critical care, lactic acid, sepsis, septic shock

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; eCART, Electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases; IQR, interquartile ratio; IVF, intravenous fluids; SEP-1, Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Sepsis is a leading cause of in-hospital death, and its incidence continues to rise, creating an ever-growing economic and health care burden.1, 2, 3 Recognition of this issue has led to the development of initiatives aimed at promoting recognition and treatment of sepsis through care bundles.4 On October 1, 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1). SEP-1 selects patients who meet two of four systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, display at least one new organ dysfunction, and have documentation of suspicion of infection. Patients who meet all three of these criteria within a 6-h period are identified as having “severe sepsis.” To meet bundle compliance, providers need to measure serum lactate, obtain blood cultures, and initiate antibiotics within a time window specified by the bundle.5 An initial serum lactate level must be drawn between 6 h before and 3 h after severe sepsis presentation, followed by a repeat within 6 h of presentation if the initial value is elevated. Given prior work suggesting lactate clearance as a goal of sepsis management, it is likely that patients with elevated values would likely receive more aggressive resuscitation.

The SEP-1 measures are intended to improve timely diagnosis and management of sepsis and are made on the basis of prior studies demonstrating the efficacy of bundles on reducing in-hospital mortality.6 It is unclear, however, whether SEP-1 captures the appropriate population or what the characteristics of this population are.7, 8 Prior evidence exists to support early antibiotic administration9; however, the evidence for early serum lactate measurement is more complex. Studies demonstrate clear correlations between elevated lactate, time to lactate clearance, and mortality in the ED and ICU.10, 11, 12 Whether measuring lactate leads to improved outcomes is unknown. Furthermore, the relationship between delays in initial lactate measurement and mortality has not been examined.

In this study, we aimed to retrospectively apply the SEP-1 definitions to a large inpatient population to identify and characterize patients who met SEP-1 criteria for severe sepsis. We assessed how frequently serum lactate levels were drawn and whether these lactate levels were associated with increased rates of interventions. Last, we aimed to characterize the relationship between delay in lactate measurement and mortality to better understand the utility of lactate measurements in sepsis management.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Adult patients admitted to the University of Chicago, an urban tertiary care medical with approximately 500 beds, from November 2008 until January 2016 who met one of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9), codes specified by SEP-1 (e-Table 1) were included in the study. The protocol was approved by the University of Chicago institutional review board (#15-1705), and a waiver of consent was granted on the basis of general impracticability and minimal harm.

Data Collection

Vital signs, laboratory, orders, ICD-9 codes, and demographic data were collected by the University of Chicago’s Clinical Research Data Warehouse, deidentified, and then made available on a secure SQL server for analysis. Nonphysiologic data points were changed to missing as per prior work.13 ICD-10 to ICD-9 cross-walking was performed to identify SEP-1 ICD-9 codes (e-Table 1). The Electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage (eCART) score, a previously developed model used to predict the risk of cardiac arrest, ICU transfer, and death on wards, was used to adjust for severity of illness.14

Identifying Patients Meeting SEP-1 Criteria

In the SEP-1 measure, patients who meet the following three criteria within a 6-h time frame are identified as demonstrating severe sepsis: (1) at least one organ dysfunction, (2) two or more SIRS criteria, and (3) documentation of suspected source of infection. Because we did not have access to provider documentation, the time of blood culture order was used as a proxy for suspicion of infection. SIRS criteria were defined per the consensus conference definition15 and organ dysfunction was defined per SEP-1 (e-Table 2), with the exceptions that urine output and drop in systolic BP > 40 mm Hg from baseline were not included as organ dysfunction criteria. Furthermore, to exclude patients with persistent organ dysfunction resulting from chronic comorbidities, we included the additional requirement that if a patient met these criteria for organ dysfunction, it must also be a change of at least 10% from that patient’s most normal value during the admission. Finally, patients with an ICD-9 code for end-stage renal disease were excluded from meeting renal organ dysfunction criteria.

Lactate Measurements

All serum lactate samples drawn for admissions meeting the SEP-1 criteria for severe sepsis were analyzed. The time difference between the time a patient met all SEP-1 criteria for severe sepsis and the time of lactate draw was calculated. Serum lactate samples that were drawn within 6 h before and 3 h after the initial time meeting severe sepsis criteria were identified as having met SEP-1 requirements for lactate measurement, as described in the CMS guidelines. Serum lactate samples drawn after 3 h were considered delayed lactate draws.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between patients of different groups using t tests, Wilcoxon rank sums, and χ2 tests as appropriate. The mean time to IV antibiotics and fluids between the different lactates groups was also tested for significance. The association between delays in initial lactate measurement and in-hospital mortality was calculated using logistic regression, with adjustment for lactate level, eCART score, location, and whether the patient had received antibiotics in the 24 h before the time of suspicion of infection. Further analysis on this model was performed with the addition of adjustment for time to initial antibiotics and IVF.

Because patients with delayed lactate measurements did not have values available at the time of suspicion of infection and because later lactate values may not reflect the initial physiology of these patients because of interventions, a linear regression model was used to impute initial lactate values at the time of meeting SEP-1 criteria for these patients, with vital signs, location, and other laboratory values as predictors. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.2 (StataCorp), and all tests of significance used a two-sided P < .05.

Results

Study Population

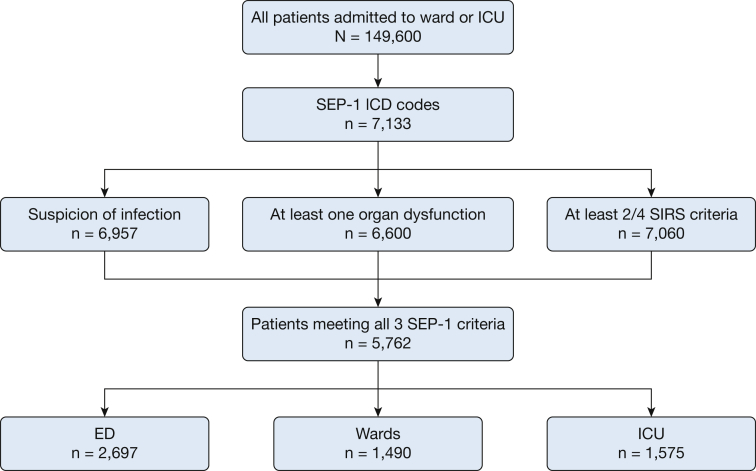

A total of 149,600 admissions occurred during the study period, of which 7,133 had at least one of the ICD-9 codes required by SEP-1 for inclusion. Ultimately, 5,762 of these admissions met all three SEP-1 criteria for severe sepsis within a 6-h time window and thus comprised the final analytic cohort (Fig 1). Forty-seven percent first met criteria in the ED (n = 2,697), 27% (n = 1,575) in the ICU, and 26% (n = 1,490) on the wards (Fig 1). Patients who first met SEP-1 criteria in the ICU had the highest mortality (40%), followed by the wards (28%) and then the ED (18%; P < .01 for all comparisons). Those who met criteria in the ICU also had the longest median length of stay (19 days), followed by the wards (18 days), and the ED (10 days; P < .01; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study patients. Suspicion of infection is defined as any patient that had a blood culture ordered. ICD = International Classification of Diseases; SEP-1 = Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle; SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Table 1.

Comparison of Patient Characteristics Between Those Who Met SEP-1 Criteria for Severe Sepsis on the Wards, ICU, and ED

| Characteristic | Ward (n = 1,575) | ICU (n = 1,490) | ED (n = 2,697) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59 (16) | 59 (16) | 60 (17) | < .001 |

| Female | 725 (46) | 621 (42) | 1,396 (52) | < .001 |

| Race | < .001 | |||

| Black | 618 (39) | 589 (40) | 1,993 (74) | … |

| White | 800 (51) | 665 (45) | 530 (20) | … |

| Other/unknown | 157 (10) | 236 (16) | 174 (6) | … |

| LOS, median (IQR), d | 18 (11-29) | 19 (11-33) | 10 (7-15) | < .001 |

| Mortality | 444 (28) | 589 (40) | 484 (18) | < .001 |

| Lactate ≤ 2.0 mmol/L | 108 (25) | 224 (35) | 109 (12) | … |

| Lactate > 2.0 and ≤ 4.0 mmol/L | 95 (38) | 126 (52) | 145 (15) | … |

| Lactate > 4.0 mmol/L | 77 (55) | 99 (62) | 184 (34) | … |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. Lactate data are made on the basis of initial lactate draws at any time after meeting SEP-1 criteria. LOS = length of stay; SEP-1 = Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle.

Serum Lactate Measurements

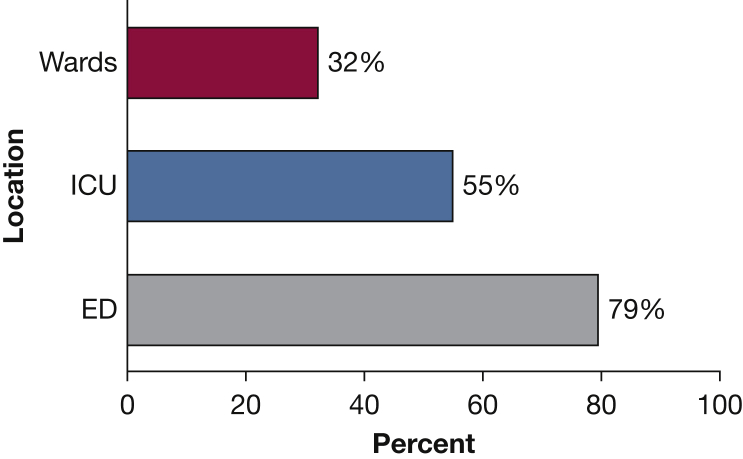

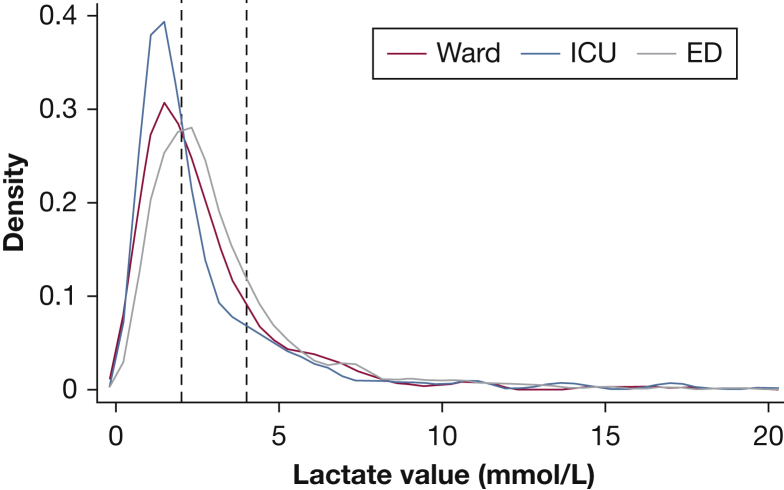

Sixty percent (n = 3,468) of the study cohort had an initial lactate drawn within the SEP-1–specified time window, with a median value of 2.4 mmol/L (interquartile range [IQR], 1.5-3.7 mmol/L). Frequency of serum lactate draws within the time window varied depending on the location where the patient first met criteria, from 32% of the patients who first met criteria on the wards vs 55% in the ICU and 79% in the ED (P < .01, Fig 2). Forty-one percent of the drawn lactates across all locations were ≤ 2.0, and 78% were ≤ 4.0 (Fig 3). Delayed lactates, defined as lactate samples drawn between 3 and 24 h after the time of suspicion of infection, were drawn for 14% (n = 803) of the patients meeting severe sepsis criteria. Last, 26% (n = 1,491) of the patients did not have a lactate drawn within 24 h of suspicion of infection (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Percent of patients who had lactates drawn within Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services window, by location.

Figure 3.

Distribution of lactate levels drawn within Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services SEP-1 window. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Table 2.

Comparison of Characteristics Between Patients Who Met SEP-1 Criteria and Had Lactate Levels Drawn Within the Specified SEP-1 Window, After the Window, or Not at All

| Characteristic | Drawn Lactates (n = 3,468) | Delayed Lactates (n = 803) | No Lactate Drawn (n = 1,491) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61 (17) | 60 (17) | 58 (16) | < .001 |

| Female | 1,701 (49) | 397 (49) | 627 (42) | < .001 |

| Race | < .001 | |||

| Black | 2,154 (62) | 402 (50) | 644 (43) | … |

| White | 1,000 (29) | 321 (40) | 674 (45) | … |

| Other/unknown | 314 (9) | 80 (10) | 173 (12) | … |

| LOS, median (IQR), d | 11 (7-19) | 15 (9-26) | 18 (11-32) | < .001 |

| Mortality | 936 (27) | 231 (29) | 350 (23) | .003 |

| Location at time of first meeting SEP-1 criteria | < .001 | |||

| Ward | 506 (15) | 308 (38) | 761 (51) | … |

| ICU | 818 (24) | 222 (28) | 450 (30) | … |

| ED | 2,144 (62) | 273 (34) | 280 (19) | … |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. See Table 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Lactate Levels and Mortality

Mortality increased with higher initial lactate levels across all locations (Table 1). In the group of patients who first met SEP-1 criteria in the ED, mortality was 12% for patients with an initial lactate measurement ≤ 2.0 mmol/L, 15% for initial lactates > 2.0 and ≤ 4.0 mmol/L, and 34% for initial lactates > 4.0 mmol/L (P < .001). On the wards, respective mortality rates were 25%, 38%, and 55% (P < .001). In the ICU, mortality rates were 35%, 52%, and 62% (P < .001).

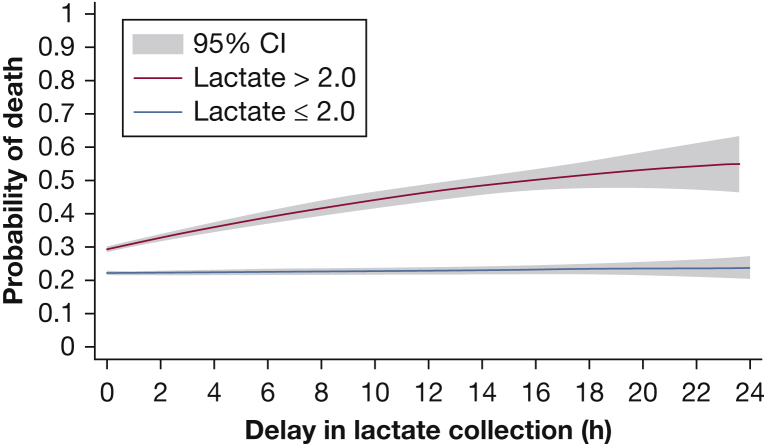

Delays in Lactate Draws and Outcomes

Length of stay was longest for patients who never had lactates drawn (median, 18 days; IQR, 11-32 days), followed by those with delayed lactates (median, 15 days; IQR, 9-26 days), whereas patients who had a lactate sample drawn in the SEP-1 window had the shortest length of stay (median, 11 days; IQR, 7-19 days; P < .01). Patients with delayed lactates had the highest in-hospital mortality (29%), followed by those with lactate samples drawn within the CMS window (27%) and then those without a lactate sample (23%; P < .01; Table 2). The relationship between delay in initial lactate measurement and the probability of in-hospital death is seen in Figure 4. In patients with an initial lactate value ≤ 2.0, regardless of whether this lactate sample was drawn within the CMS specified time window or not, there was no increase in mortality associated with delay in lactate draw after meeting severe sepsis criteria on adjusted analysis (OR, 0.997; CI, 0.97-1.02; P = .77). However, in patients with an initial lactate value > 2.0, a statistically significant increase in mortality is seen with each hour of delay in initial lactate draw associated with a 2% increase in the odds of death in adjusted analysis (OR, 1.02; CI, 1.0003-1.05; P = .04). When adjusted for time to antibiotics and IVF, this association was no longer significant (P = .51).

Figure 4.

Relationship between delay in initial lactate measurement and the probability of in-hospital mortality for patients meeting SEP-1 criteria, stratified by level of initial lactate value (mmol/L) and adjusted for patient location, Electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage score, and lactate value. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Time to Intervention

Patients who had lactate samples drawn within the specified window received their first dose of antibiotics or first IVF bolus more quickly than those with delayed lactate draws, with a median of 2.0 h to antibiotics (IQR, 0.7-5.2 h) and 1.3 h to IVF bolus (IQR, 0.4-6.6 h) compared with 3.9 h to antibiotics (IQR, 1.7-10.5 h) and 4.8 h to IVF bolus (IQR, 1.0-17.9 h) in the delayed draw group (P < .0001; Table 3). The association between higher lactate values and earlier receipt of antibiotics and IVFs remained significant after adjusting for severity of illness (ie, eCART; P < .01).

Table 3.

Time to Interventions (IV Antibiotics or IVF Bolus) After Patients Met SEP-1 Criteria

| Population | Time to Lactate Draw Median (IQR), h |

Time to Antibiotics Median (IQR), h |

Time to IVF Median (IQR), h |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 0.3 (0-1.7) | 2.8 (1.0-10.4) | 2.3 (0.6-18.5) |

| All drawn lactates | 0.01 (0-0.8) | 2.0 (0.7-5.2) | 1.3 (0.4-6.6) |

| Drawn lactates ≤ 2 mmol/L | 0.7 (0-3.4) | 2.7 (1.0-7.6) | 2.0 (0.6-13.0) |

| Drawn lactates > 2 mmol/L | 0.02 (0-1.1)a | 1.6 (0.6-4.2)b | 1.1 (0.4-4.5)b |

| Delayed lactates | 7.5 (4.9-13.0)c | 3.9 (1.7-10.5) | 4.8 (1.0-17.9) |

| No lactate drawn | 9.5 (2.5-51.4) | 30.7 (3.8-133.6) |

Significant vs drawn lactates ≤ 2 mmol/L.

Significant compared with all other groups, P < .05.

Significant vs all drawn lactates group. IVF = IV fluids. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Discussion

In this study, we found that lactate levels were checked in the mandated time window with greater frequency in patients who first met severe sepsis criteria in the ED rather than the wards or ICU. Regardless of where patients first met criteria, however, a significant proportion of the initial lactate values were < 2.0 mmol/L. Delays in initial lactate measurement were associated with increased mortality, but only for those patients with an initial lactate value > 2.0 mmol/L. This may have occurred because patients who had lactate samples drawn within the SEP-1 window, particularly those with a lactate >2.0 mmol/L, received earlier interventions than those who had a delayed lactate draw.

Sepsis bundles have often focused on ED patients, but our study demonstrates that a large number of patients become newly septic on the wards and have higher mortality than those who initially meet criteria in the ED. This is an important population of patients in which to effectively and quickly identify and treat sepsis. Furthermore, 61% of all patients had lactate levels checked within the SEP-1 window, but only 32% of patients on the wards met this measure. Many of the lactate levels drawn were < 2.0 mmol/L, and the vast majority were < 4.0 mmol/L. Full compliance with SEP-1 protocol would lead to a significant increase in lactate measurements, with uncertain consequences as to how providers would react to many additional normal lactate values.

Several studies have shown that intermediate lactate values are associated with increased mortality in the ED.12, 16 A subsequent study by the Liu et al17 found that implementing a treatment bundle for ward patients with sepsis and an intermediate lactate was associated with improved hospital mortality, suggesting that interventions in patients with lactate levels > 2.0 mmol/L may be of benefit in sepsis. Our analysis complements these prior studies, finding that delays in initial lactate draw were associated with increased mortality, but only in patients with an initial lactate > 2.0 mmol/L. With each hour of delay in measuring a lactate, the odds of mortality for this group of patients rose by 2%, whereas the mortality of patients with a normal lactate level remained unchanged. This association between delay in lactate draw and mortality is likely mediated by the effect of lactate draws on subsequent patient interventions. When our mortality model was adjusted for time to antibiotics and IVF, there was no longer a significant association between delay in lactate and mortality. Our study demonstrates that patients with lactates drawn within the SEP-1 window received both IV antibiotics and fluids sooner than their counterparts who had lactates drawn outside of the window. Among the patients with lactate levels drawn within the window, those with lactate levels > 2.0 mmol/L receive interventions more quickly than those with normal lactates. However, even patients with a normal lactate drawn within the SEP-1 window received interventions more frequently and more quickly than those with delayed lactates or those who never had a lactate drawn. Although it is possible that some patients would have received earlier interventions regardless of whether their lactate was checked or not, our finding of an association between earlier interventions with higher lactate values existed even after adjusting for severity of illness suggests that the lactate result itself may have led clinicians to take earlier action.

Prior studies on SEP-1 have focused on ED patients, overall bundle compliance, and field implementation. Venkatesh et al18 described hospital-level compliance with the SEP-1 bundle across 50 hospitals, with a focus on ED sepsis management, whereas Ramsdell et al19 examined compliance before and after SEP-1 implementation at a single center. Both studies showed variability in compliance with some improvement with time. Ours is the first to study patients in the wards, ED, and ICU, and to examine the effect of lactate delay on mortality. Our findings show that both intermediate and high initial lactate levels are associated with increased mortality, and that there is also an association between delayed lactate draws and increased mortality; however, many patients who meet severe sepsis criteria ultimately have normal lactate values. These observations suggest that although elements of the SEP-1 bundle are useful in managing sepsis, the measure may also lead to an increase in lactate measurements and subsequently excessive utilization of resources on patients who may not benefit.

Our study has several limitations. It is a single-center investigation and may not be generalizable to other practice settings. Second, we lacked the ability to review provider documentation and instead used the time of blood culture order as a surrogate marker for suspicion of infection. This prevented us from being able to identify the sources of infection, which has been studied in the past for its association with mortality in sepsis and septic shock.20, 21, 22 Finally, because this was not a randomized controlled trial, our finding of delayed lactate measurements associated with increased mortality could be due to unmeasured confounding, such as comorbidities or immunosuppression status, or through a mechanism other than earlier antibiotic and IVF administration.

Conclusions

In our study, we found that patients with elevated lactate levels demonstrated increased mortality in all hospital settings and that delays in lactate measurements for patients with initial abnormal lactates were associated with progressive increases in mortality. These patients also experienced longer time to intervention, as defined by time to administration of IVF and antibiotics, the latter of which has been shown to be associated with increased mortality in sepsis when delayed.9, 23 Systematic early lactate measurements when a patient presents with sepsis may thus be useful in prompting earlier, potentially life-saving interventions.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Study concept and design: X. H., M. M. C., M. D. H., D. P. E.; acquisition of data: M. M. C. and D.P.E.; analysis and interpretation of data: all authors; first draft of the manuscript: X. H.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: A. S., X. H., M. M. C.; obtained funding: M. M. C.; administrative, technical, and material support: M. M. C., X. H., S. S., N. P., A. S.; study supervision: M. M. C. and D.P.E; data access and responsibility: X. H., M. M. C., and A. S. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M. M. C. is the guarantor of the content of this manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: M. M. C. has received honoraria from CHEST for invited speaking engagements. M. M. C. and D. P. E. have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. D. P. E. has received research support and honoraria from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), research support from the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway), and has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. None declared (A. S., N. P., S. S., C. B., M. D. H.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This research was funded in part by an ATS Foundation Recognition Award for Outstanding Early Career Investigators grant (principal investigator: Dr Matthew Churpek). Dr Churpek is also supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant K08 HL121080].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Liu V., Escobar G.J., Green J.D. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312:90–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin G.S., Mannino D.M., Eaton S., Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus D.C., Line-Zwirble W.T., Lidicker J., Clermont G., Carcillo J., Pinsky M.R. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellinger R.P., Levy M.M., Rhodes A., Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures Discharges 10-01-15 (4Q15) through 06-30-16 (2Q16). Specifications manual for National Inpatient Quality Measures. The Joint Commission. 2016.

- 6.Nguyen H.B., Corbett S.W., Steel R. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1105–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259463.33848.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septich Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seymour C.W., Liu V.X., Iwashyna T.J. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):762–774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seymour C.W., Gesten F., Prescott H.C. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2235–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro N.I., Howell M.D., Talmor D. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(5):524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen H.B., Loomba M., Yang J.J., Jacobsen G., Shah K., Otero R.M. Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1637–1642. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000132904.35713.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikkelsen M.E., Miltiades A.N., Gaieski D.F. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1670–1677. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churpek M.M., Zadravecz F.J., Winslow C., Howell M.D., Edelson D.P. Incidence and prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ dysfunctions in ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(8):958–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0275OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churpek M.M., Yuen T.C., Winslow C. Multicenter development and validation of a risk stratification tool for ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(6):649–655. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1022OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bone R.C., Balk R.A., Cerra F.B. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu V., Morehouse J.W., Soule J., Whippy A., Escobar G.J. Fluid volume, lactate values, and mortality in sepsis patients with intermediate lactate values. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(5):466–473. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201304-099OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu V.X., Morehouse J.W., Marelich G.P. Multicenter implementation of a treatment bundle for patients with sepsis and intermediate lactate values. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1264–1270. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1489OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatesh A.K., Slesinger T., Whittle J. Preliminary performance on the new CMS sepsis-1 national quality measure: early insights from the Emergency Quality Network (E-QUAL) Ann Emerg Med. 2017;71(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsdell T.H., Smith A.N., Kerkhove E. Compliance with updated sepsis bundles to meet new sepsis core measure in a tertiary care hospital. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(3):177–186. doi: 10.1310/hpj5203-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esper A.M., Moss M., Lewis C.A., Nisbet R., Mannino D.M., Martin G.S. The role of infection and comorbidity: factors that influence disparities in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2576–2582. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239114.50519.0E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahar J.R., Timsit J.F., Garrouste-Orgeas M. Outcomes in severe sepsis and patients with septic shock: pathogen species and infection sites are not associated with mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(8):1886–1895. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b827c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leligdowicz A., Dodek P.M., Norena M., Wong H., Kumar A., Kumar A. Association between source of infection and hospital mortality in patients who have septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(10):1204–1213. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1875OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar A., Roberts D., Wood K.E. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.