Abstract

Background and Aims

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation [AHSCT] is a therapeutic option for patients with severe, treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease [CD]. The evidence base for AHSCT for CD is limited, with one randomised trial [ASTIC] suggesting benefit. The aim of this study was to evaluate safety and efficacy for patients undergoing AHSCT for CD in Europe, outside the ASTIC trial.

Methods

We identified 99 patients in the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation [EBMT] registry, who were eligible for inclusion. Transplant and clinical outcomes were obtained for 82 patients from 19 centres in seven countries.

Results

Median patient age was 30 years [range 20–65]. Patients had failed or been intolerant to a median of six lines of drug therapy; 61/82 [74%] had had surgery. Following AHSCT, 53/78 [68%] experienced complete remission or significant improvement in symptoms at a median follow-up of 41 months [range 6–174]; 22/82 [27%] required no medical therapy at any point post-AHSCT. In patients who had re-started medical therapy at latest follow-up, 57% [24/42] achieved remission or significant symptomatic improvement with therapies to which they had previously lost response or been non-responsive. Treatment-free survival at 1 year was 54%. On multivariate analysis, perianal disease was associated with adverse treatment-free survival (hazard ratio 2.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.14–4.83, p = 0.02). One patient died due to infectious complications [cytomegalovirus disease] at Day +56.

Conclusions

In this multicentre retrospective analysis of European centres, AHSCT was relatively safe and appeared to be effective in controlling otherwise treatment-resistant Crohn’s disease. Further prospective randomised controlled trials against standard of care are warranted.

Keywords: Autoimmune disease; autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplant, Crohn’s disease

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease [CD] is an immunologically mediated chronic disease characterised by episodic intestinal inflammation and dysregulation of the mucosa-associated immune system.1 Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents are the mainstay of therapy, but up to 25% of patients remain refractory to optimal medical therapy, and a further 50% experience loss of response.2,3 Treatment-refractory CD is associated with adverse quality of life, recurrent hospitalisation, and increased mortality.4,5

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation [AHSCT] is a potential therapeutic option for treatment-refractory CD.6 AHSCT may lead to remission in CD by chemotherapy-mediated ablation of inflammatory cells followed by marrow reconstitution and restoration of immune tolerance.7 The mechanisms underlying this process are incompletely defined, but thymic re-activation, broadening of the total T, B, NK cell, and plasma cell repertoire, and resetting of regulatory T cell function, have been suggested to play a role.8

Clinical experience of AHSCT for CD is limited, with several small series suggesting clinical benefits.9–18 In a Phase 1/2 study of 24 patients with severe treatment-refractory CD, AHSCT resulted in clinical relapse-free survival of 91% at 1 year and 19% at 5 years, with a rapid and sustained improvement in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI] post AHSCT.10 Only one randomised trial of AHSCT for CD [ASTIC] has been reported to date.19 This study enrolled patients with active CD not amenable to surgery and unresponsive to treatment with three or more immunosuppressive/biologic agents to AHSCT [n = 23] or control [mobilisation and AHSCT deferred for 1 year, n = 22]. One patient died of sepsis and hepatic veno-occlusive disease, and the trial failed to meet its primary endpoint of clinical and endoscopic ‘cure’ at 1 year, a composite of freedom from disease on imaging and endoscopy, CDAI < 150 and no active treatment for 3 months. This has been criticised for being overly stringent, and patients demonstrated sustained improvement on pre-specified secondary endpoints.19,20

European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation [EBMT] guidelines, published in 2012, have included recommendations for AHSCT in CD types: i] active and unresponsive disease despite multiple lines of therapy; ii] extensive disease where surgical resection would expose the patient to small bowel syndrome risk; and iii] refractory colonic disease where a stoma is not acceptable to the patient.6 As the number of patients undergoing AHSCT in any centre to date are limited, multicentre studies are required. EBMT maintains a registry of all patients undergoing AHSCT for any indication, and provides a means to identify the total European cohort. We therefore designed this retrospective study to evaluate the clinical use and outcomes of all AHSCT in CD performed in EBMT transplant centres outside the ASTIC trial.

2. Methods

2.1. EBMT registry

EBMT is a not-for-profit medical and scientific organisation that represents over 500 HSCT centres from over 50 countries. The EBMT registry now contains details on over 500000 allogeneic and autologous transplants performed since 1986. All patients included in the registry give written consent before transplant for the collection and analysis of anonymised data. The data are maintained in the central EBMT registry in line with legal and regulatory requirements for data protection, confidentiality, and accuracy. EBMT implements regular quality assurance measures including ensuring centre accreditation, regular cross-checks with national registries, annual surveys, and regular audit processes. This study was performed in line with EBMT guidelines and approved by the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party [ADWP].

2.2. Patient population

Patients who underwent AHSCT for Crohn’s disease were identified from the EBMT registry. All adult patients [aged ≥18 years at time of AHSCT] undergoing AHSCT for a primary diagnosis of CD from 1997 to 2015 were eligible for inclusion. Patients who had participated in the ASTIC trial were excluded. From a total of 99 patients across 27 centres, data were obtained for 82 patients transplanted in 19 centres in eight countries from 1996 to 2015[see Supplementary data available at ECCO-JCC online]. Data were unavailable for 17 patients due to lack of response to repeated requests.

2.3. Study endpoints

Transplant and clinical outcomes for each patient were obtained directly from the EBMT registry supplemented by a standardised questionnaire completed by the treating clinicians in each centre. The primary study endpoint was clinical disease response [defined below] assessed by the patient’s gastroenterologist 1 year following AHSCT, as compared with pre-mobilisation clinical status. Secondary endpoints included overall survival [OS], transplant-related mortality [TRM], treatment-free survival, and clinical disease response to mobilisation, at 100 days and at latest clinical assessment. Variables considered for descriptive analyses were medical/surgical therapy pre- and post-AHSCT, disease extent and behaviour pre- and post-AHSCT, and neutrophil and platelet engraftment dates. Data on complications post-AHSCT were recorded, including infectious complications requiring hospitalisation [bacterial, viral, or fungal] up until 12 months post-AHSCT, and incidence of malignancy and secondary autoimmune disease post-AHSCT.

2.4. Definitions

Clinical disease response was categorised as:

remission: no abdominal pain and normal stool frequency;

improvement: improvement in abdominal pain and/or stool frequency;

stable/no change: no appreciable improvement in abdominal pain and/or stool frequency;

worse: deterioration in abdominal pain and/or stool frequency.

The introduction, reduction, or withdrawal of steroids, immunomodulators, or biologic therapy, and need for further surgical therapy, were also recorded.

Disease behaviour was assessed as stricturing, penetrating, both, or neither, pre- and post-AHSCT [Supplementary Table 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as time from day of transplant until Day 1 of 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count ≥0.5 x 10^9/L, whereas platelet engraftment was defined as time from day of transplant until Day 1 of 3 consecutive days with a platelet count ≥20 x 10^9/L. Treatment- related mortality [TRM] was defined as any death after AHSCT within the first 100 days post-AHSCT. Treatment-free survival was defined as survival from transplantation without major surgery or medical therapy.

2.5. Statistics

Qualitative variables were described as percentage, continuous variables using median and range. Overall survival and treatment-free survival were calculated according to the method of Kaplan and Meier. Variables considered in univariate and multivariate analyses of disease response and treatment-free survival were recipient age at AHSCT [>/≤median], time from diagnosis to AHSCT [>/≤median], patient sex [male vs female], disease classification [limited vs extensive without perianal disease vs extensive with perianal disease], disease behaviour [non-stricturing/non-penetrating vs stricturing vs penetrating], and pre-transplant smoking status. For treatment-free survival, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the independent effect of covariates on outcome. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 24 [SPSS Inc./IBM, Armonk, NY, USA] and R 3.4.0 [R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria] software packages.

3. Results

3.1. Patient and disease characteristics

Patient and disease characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Median patient age was 30 years [range 20–65] and 52/82 [63%] were female. Median age at first diagnosis of CD was 17 years [range 2–53]. Details of previous therapies are outlined in Table 2. Patients were heavily pre-treated, having failed or been intolerant to a median of six previous lines of therapy [range 3–10]; 44/82 [54%] had received experimental therapy before AHSCT. This included participation in clinical trials of experimental immunosuppressants, faecal transplant, leukocytapheresis, or mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Previous surgical treatment was common, with 61/82 [74%] of patients having undergone at least one operation. The median time from first diagnosis of CD to AHSCT was 12 years [range 1–26]. Median length of follow-up following AHSCT was 41 months [range 6–174].

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics.

| Characteristic | n [%] |

|---|---|

| Patient sex [female/male] | 52 [63%] F/30 [37%] M |

| Median age at AHSCT [yrs] | 30 [20–65] |

| Median age at diagnosis [yrs] | 17 [2–53] |

| Extra-intestinal involvement at diagnosis | |

| None | 54 [67%] |

| Joints+/-skin | 15 [18%] |

| Skin | 5 [6%] |

| PSC | 2 [3%] |

| Other | 4 [5%] |

| Median time from diagnosis to AHSCT [yrs] | 12 [1–26] |

| Disease classification at mobilisation | |

| Limited | 35 [46%] |

| Extensive without perianal disease | 20 [26%] |

| Extensive with perianal disease | 21 [28%] |

| Disease behaviour at mobilisation | |

| Stricturing | 17 [21%] |

| Penetrating | 8 [10%] |

| Stricturing+penetrating | 14 [17%] |

| Non-stricturing/non-penetrating | 42 [52%] |

| Perianal | 23 [28%] |

| Median follow-up [months] | 41 [6–174] |

F, female; M, male; yrs, years; AHSCT, autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplant; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Table 2.

Previous therapies.

| Details | n [%] |

|---|---|

| Previous surgery | 61 [74%] |

| Ileostomy | 18 [22%] |

| Colostomy | 5 [6%] |

| Small bowel resection | 24 [29%] |

| Ileocaecal resection | 27 [33%] |

| Partial colectomy | 14 [17%] |

| Total colectomy | 11 [13%] |

| Proctectomy | 6 [7%] |

| Strictureplasty | 11 [13%] |

| Seton insertion | 13 [16%] |

| Other | 17 [18%] |

| Previous lines of drug therapy | 6 [3–10] |

| Corticosteroids | 82 [100%] |

| Thiopurine | 78 [98%] |

| Methotrexate | 66 [82%] |

| Anti-TNF | 81 [99%] |

| Anti-integrin | 16 [20%] |

| Primary enteral nutrition | 23 [28%] |

| Experimental or other drugs | 44 [54%] |

| Experimental biological therapy [IL6/IL2/IL10/IL17/ CCR9/gamma IFN/HDAC inhibition] | 10 [12%] |

| Ustekinumab | 8 [10%] |

| Thalidomide | 4 [5%] |

| Anti-MAd-CAM | 3 [4%] |

| Faecal transplant | 3 [4%] |

| Cyclophosphamide | 3 [4%] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | 2 [2%] |

| Leukocytapheresis | 2 [2%] |

| Other | 9 [11%] |

TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

3.2. AHSCT characteristics and haematological outcomes

AHSCT details are summarised in Table 3. All patients underwent mobilisation with cyclophosphamide, and peripheral blood stem cells were re-infused a median of 2 months [range 1–16] later. Patients received conditioning with cyclophosphamide 200 mg/kg and 69/82 [86%] underwent in vivo T cell depletion with anti-thymocyte globulin [ATG]. The median dose of ATG was 7.5 mg/kg [range 2.0–10.0]. The median CD34+ dose infused was 5.4 [range 2.4–40.6] x 10^6/kg. CD34+ selection of the autologous graft was performed in 11% of patients, and the remained were unmanipulated. All patients engrafted successfully. Neutrophil and platelet engraftment both occurred at a median of Day 10 [range 6–22 and 6–44, respectively]; 62% received post-transplant granulocyte colony stimulating factor [G-CSF].

Table 3.

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplant [AHSCT] details.

| Mobilisation regimen: | |

|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide/G-CSF | 72 [91%] |

| G-CSF alone | 2 [3%] |

| Conditioning regimen: | |

| Cyclophosphamide/ATG | 69 [86%] |

| Cyclophosphamide/CD34+ selection | 9 [11%] |

| Median dose CD34+ [x 10^6/kg] | 5.4 [2.4–40.6] |

| Median time to neutrophil engraftment /days | 10 [6–22] |

| Median time to platelet engraftment /days | 10 [1–44] |

| Engraftment | 82 [100%] |

G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin.

3.3. CD outcomes

One-year follow-up data were available for 76 patients [93%], as one patient died at 56 days and data unavailable for four patients; 33/76 [43%] were in CR, 15/76 [20%] were reported as improved, 13/76 [17%] were unchanged, and 15/76 [20%] had worsened.

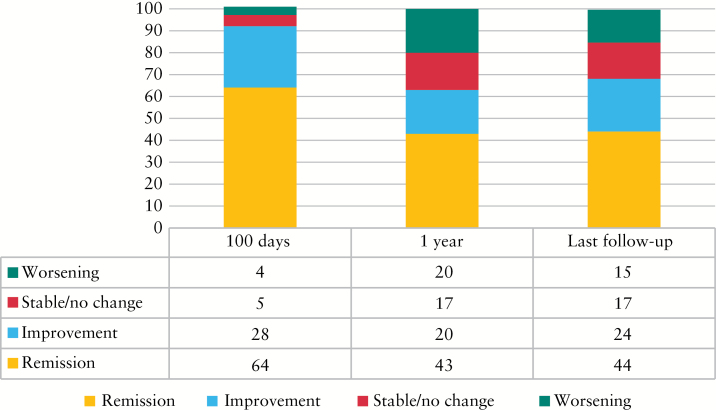

At 100 days post AHSCT, data were available for 80 patients; 51/80 patients [64%] were in clinical remission [CR]. A further 22/80 [28%] reported improvement. For 4/80 [5%] there was no change in disease, and in 3/80 [4%] the disease worsened compared with baseline. At latest follow-up, data were available for 78 patients; 34/78 [44%] were in CR, 19/78 [24%] were improved, 13/78 [17%] were unchanged, and 12/78 [15%] had worsened [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Clinical disease response. Percentage of patients in each clinical disease response category [remission, improvement, stable disease, and worsening] at 100 days, 1 year and latest follow-up [median 3.4 years].

Predictors of achieving clinical disease remission or disease response [either remission or improvement] at 1 year were evaluated. There was no statistically significant impact of age at diagnosis, age at AHSCT, pre-transplant smoking status, time from diagnosis to AHSCT, patient sex, previous surgery, disease classification, or disease extent on the likelihood of achieving remission or disease response at 1 year.

Treatment-free survival was 54.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 43.8 - 65.5%) at 1 year, and 27% [95% CI 17–38%] and 22% [95% CI 11–33%] at 3 and 5 years, respectively. There were no significant predictors of treatment-free survival identified on univariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, extensive disease with perianal disease was found to be an independent predictor for adverse treatment-free survival with a hazard ratio of 2.34 [95% CI 1.14–4.83, p-value 0.02] [see Table 4 for results of multivariate analysis].

Table 4.

Results from multivariate analysis for treatment-free survival.

| Variables | HR | CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at HSCT > median [30 years] | 0.81 | 0.41–1.57 | 0.53 | |

| Time from diagnosis to HSCT > median [141 months] | 1.20 | 0.65–2.23 | 0.56 | |

| Female vs male | 1.39 | 0.80–2.48 | 0.26 | |

| Disease classification | Limited [ref] | 1 | ||

| Extensive with perianal disease | 1.61 | 0.77–3.37 | 0.20 | |

| Extensive without perianal disease | 2.34 | 1.14–4.83 | 0.02 | |

| Smoker pre-transplant | 1.64 | 0.85–3.15 | 0.14 | |

| Disease behaviour [three classes] | Non-stricturing/non-penetrating [ref] | 1 | ||

| Stricturing | 1.11 | 0.56–2.21 | 0.76 | |

| Penetrating | 0.61 | 0.28–1.32 | 0.21 | |

HSCT, haematopioetic cell transplant; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.4. Mortality and complications

One patient died at Day +56 post-AHSCT due to CMV infection, sepsis, and multiorgan failure, i.e. a transplant-related mortality of 1.2%. Another patient died at 7.99 years post-AHSCT from sepsis and multi-organ failure. In the year post-AHSCT, 22/82 [27%] developed an infection requiring treatment after AHSCT (9/82 [%] bacterial, 11/82 [12%] viral). Epstein-Barr virus [EBV] and CMV reactivation occurred in 5/82 [6%] and 3/82 [4%], respectively. There were no cases of fungal infection.

During follow-up post-AHSCT, a secondary autoimmune disease was reported in 9/82 [13%]. These included thyroid disease [5/82; 6%], rheumatoid arthritis [2/82; 2%], and inflammatory disorders [enthesopathy, neuritis, myelitis].

New malignancy developed in 5/82 [6%, three cases of skin malignancy, one each of testicular and prostate cancer]. The median time to diagnosis was 40 months [range 38–105] after AHSCT; 18/82 [23%] had other complications reported, which included drug effects [adrenal insufficiency secondary to corticosteroids; marrow toxicity presumed secondary to mercaptopurine] and late effects with uncertain links to AHSCT [hypertension, fibromyalgia, type 2 diabetes mellitus].

Five patients successfully conceived after AHSCT, leading to the births of healthy infants.

3.5. Post-AHSCT treatment of Crohn’s disease

In all, 73% [60/82 patients followed up] resumed medical therapy for Crohn’s disease at a median of 10 months [range 1–79] after AHSCT. A total of 37% [30/82] required some form of surgery post-AHSCT, of whom 21/82 [26%] underwent major gastrointestinal [GI] surgery [laparotomy, resection, or formation of a stoma] at a median of 26 months [range 6–87]. Stoma reversal was performed in 4/82 [5%] patients post-HSCT due to disease regression.

At latest follow-up, 42/78 patients [54%] were on treatment. In patients who had re-initiated medical therapy at latest follow-up, 24/42 [57%] achieved remission or significant symptomatic improvement with therapies (including anti-tumour necrosis factor [TNF] therapy in 19/24) to which they had previously lost response or been non-responsive.

4. Discussion

The principal finding of this retrospective survey using the EBMT registry is that AHSCT in patients with severe, treatment-refractory CD can induce complete remission or significant improvement in around two-thirds [68%] at long-term follow-up; 55% were alive and off all treatment at 1 year. In a multivariate analysis, extensive disease with perianal disease was associated with adverse treatment-free survival. This is in keeping with the results of ASTIC, which demonstrated that patients with perianal disease or current smokers had a higher incidence of complications following AHSCT.20 As such, patients with perianal disease should be considered to be at higher risk of complications and relapse requiring re-initiation of treatment. An appreciable minority of 27% remained off all therapy until latest follow-up, and 57% of patients who recommenced medical therapy following AHSCT were re-sensitised to therapies to which they had previously been refractory.

Although AHSCT alone does not frequently result in cure or long-term remission, it appears to have profound benefit in this highly refractory and difficult to treat patient population, where disease control and associated quality of life are poor, and life expectancy is reduced. Of note, chronic active CD treated with intense immunosuppressive regimens in the absence of AHSCT is also associated with significant morbidity and increased mortality.21 This is the largest cohort of patients undergoing AHSCT for CD reported to date, and adds significantly to the evidence supporting its efficacy.

A further important finding of this study is that the safety of AHSCT in this population is similar to AHSCT for other common indications, such as myeloma and lymphoma, reflected by a transplant-related mortality of 1.2%.7 There was one transplant-related death in our cohort, and a second patient died at 7.99 years; 28% developed an infection post-transplant, in keeping with transplant-associated infective complications in other diseases. The three cases of skin cancer observed may be linked to the longstanding multi-agent immunosuppression experienced by this patient cohort. Optimising supportive care and restricting AHSCT to experienced centres has been shown to help mitigate AHSCT risk.22,23

In accordance with the Joint Accreditation Committee-ISCT and EBMT [JACIE] requirements, all AHSCT procedures in Europe are reported to the EBMT registry. The majority of patients in this study were treated following the 2012 EBMT Guidelines, which formed the basis for patient selection and transplant technique.6 Through pan-European multicentre collaboration, we were able to obtain patient-level data, including long-term follow-up. As a retrospective evaluation, however, our study has intrinsic limitations. First, evaluation of clinical response was performed retrospectively. However, to reduce the risk of recall bias, contemporaneous notes were reviewed in all cases. To ensure accurate information, data collection was performed by the patient’s treating gastroenterologist. Second, the categorisation of clinical response was necessarily broad, which is unlikely to fully reflect the spectrum of clinical disease response. We elected not to collect imaging, endoscopic, or biomarker outcomes, as these investigations were not performed in a systematic manner for all patients. Finally, data were not available on quality of life outcomes. Outcomes from a subset of 19 patients in this cohort have been previously reported in a single-centre study.17

ASTIC is the only randomised controlled trial of AHSCT for CD to date.19 The 1-year follow-up data of 40 transplant recipients in ASTIC provide further evidence of efficacy, with complete endoscopic healing occurring in 50% of patients, and 47% were judged free of disease on endoscopy and imaging at 1 year.20 There was also a significant improvement from baseline to 1 year after transplant across multiple clinical, quality of life, and endoscopic endpoints. Those who did relapse were re-sensitised to TNF therapy to which they had previously been refractory, as in our study.20 Single-centre studies with longer-term follow-up have reported that AHSCT does not offer indefinite remission and, as in our study, high rates of restarting medical therapy are observed.10,17 However, CD appears to be more responsive to therapy after AHSCT even where a clinical relapse occurs. Against this background, our findings lend support to a strategy of AHSCT with re-introduction of drug therapy to enable longer-term remissions in this complex patient cohort.

Recently, ECCO and EBMT have produced a collaborative update and review of the field, offering specific guidance on the clinical role of AHSCT and how it should be delivered.24 We propose that future CD patients undergoing AHSCT outside clinical trials are enrolled in a European registry study to ensure harmonisation of outcome assessment. Although our data suggest a complication rate similar to other indications for AHSCT, it must be recognised that AHSCT represents an intensive therapy with significantly higher short-term risks than conventional treatments for CD. Late effects are a risk both for AHSCT and more conventional immunosuppressive therapies, due to the cumulative burden of many intense lines of treatment in these complex patients, which even in the absence of AHSCT is associated with significant morbidity and increased mortality.21 Such late effects are broad in spectrum, affect many organ systems, and require systematic evaluation. Our current study highlights some of the issues, for example the skin cancers and secondary autoimmune disease.25 Long-term follow-up of patients combined with prospective data collection should help to evaluate these risks post-AHSCT.

The mechanism of action of AHSCT in CD remains ill-defined. AHSCT has been shown to drive profound changes to the innate and adaptive immune system.7,26 First, cytotoxic chemotherapy in combination with T cell depletion ablates autoreactive effector cells that may have been refractory to previous immunosuppressive and biologic therapies. Next, the immune system regenerates with thymic reactivation and diversification of the T cell receptor repertoire. New, tolerant regulatory T cells traffic and suppress re-emergent autoreactive T effector cells. A small pilot study provides some evidence that the immunomodulatory effects of AHSCT apply in CD, with an increase in Foxp3+ T regulatory cells and a reduction in cytokine-secreting effector cells.27 In CD, there may be additional effects from mobilisation and induction chemotherapy on the gastrointestinal mucosa, changes to the microbiome, and effects from G-CSF and antibiotics. It is likely that a combination of these factors underlies the disease response and regain of responsiveness to agents to which patients were previously refractory.

In conclusion, this study supports the safety and efficacy of AHSCT in patients with severe CD, yielding long-term clinical remissions in a patient cohort refractory to existing medical therapy. Important questions remain. These include defining parameters for selection of the patient subgroup most likely to respond to AHSCT, whether reduced-intensity conditioning regimens could improve safety and reduce toxicity, and whether the effect of AHSCT can be optimised with early introduction of post-AHSCT maintenance therapy. Optimising supportive care and restricting AHSCT to experienced centres is likely to help mitigate AHSCT risk.22 Additionally, greater insight into the mechanisms by which AHSCT induces self-tolerance may open the door to novel targeted therapies. Further randomised clinical studies are warranted to assess the role of AHSCT in this challenging disease.

Funding

JS: financial support for research: European Union, Chief Scientist’s Office, CCUK, MRC, Wellcome Trust, Abbie Vie; lecture fees: Falk, Takeda, Abbie Vie. PH: lecture fees: Falk Foundation, Abbvie, Takeda, and Janssen. JS: lecture fees for Sanofi, Jazz, and Jannssen; consultancy for Kiadis. Financial support for research: NIHR.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

CKB, CCL, DF, CJH, SPLT, JAS designed and coordinated the study. MB was responsible for data input. ML performed the statistical analysis. MR, ER, DD, SV, PH, JF, FO, AC, JS, MK, ALS, CS collected data. CKB and JAS co-wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at ECCO-JCC online.

Acknowledgments

With many thanks to all who contributed data to this study. Specifically, we would like to thank Prof. Wolfgang Kreisel, Drs Peter Johnson, Javier López-Jiménez, Jeremy Sanderson, Inken Hilgendorf, Ian Forgacs, Mariagrazia Michieli, Tobias Gedde-Dahl, Knut Lundin, Matthew Collin, Nick Thompson, Manuel Abecasis, João Pereira da Silva, Rosanna Scimè, Mario Cottone, David Gallardo, David Busquets, Achilles Anagnostopoulos, Jannis Kountouras, Rafael Duarte, Yago González-Lama, Alan Lobo, Martin Bornhäuser, Renate Schmelz, and Andy Peniket. We are indebted to the patients in this study and the multidisciplinary teams coordinating their care.

References

- 1. de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Randall CW, Vizuete JA, Martinez N, et al. From historical perspectives to modern therapy: a review of current and future biological treatments for Crohn’s disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2015;8:143–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: Part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wolters FL, Russel Mg, Sijbrandij J, et al. Crohn’s disease: increased mortality 10 years after diagnosis in a Europe-wide population based cohort. Gut 2006;55:510–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Annese V, Duricova D, Gower-Rousseau C, Jess T, Langholz E. Impact of new treatments on hospitalisation, surgery, infection, and mortality in IBD: a focus paper by the epidemiology committee of ECCO. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:1876–4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Snowden JA, Saccardi R, Allez M, et al. Haematopoietic SCT in severe autoimmune diseases: updated guidelines of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012;47:770–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swart JF, Delemarre EM, van Wijk F, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:244–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delemarre EM, van den Broek T, Mijnheer G, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation benefits autoimmune patients through functional renewal and TCR diversification of the regulatory T cell compartment. Blood 2016;127:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burt RK, Traynor A, Oyama Y, Craig R. High-dose immune suppression and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in refractory Crohn disease. Blood 2003;101:2064–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burt RK, Craig RM, Milanetti F, et al. Autologous nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with severe anti-TNF refractory Crohn disease: long-term follow-up. Blood 2010;116:6123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lopez-Cubero SO, Sullivan KM, McDonald GB. Course of Crohn’s disease after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Gastroenterology 1998;114:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kashyap A, Forman SJ. Autologous bone marrow transplantation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma resulting in long-term remission of coincidental Crohn’s disease. Br J Haematol 1998;103:651–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soderholm JD, Malm C, Juliusson G, Sjodahl R. Long-term endoscopic remission of Crohn disease after autologous stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukaemia. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:613–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cassinotti A, Annaloro C, Ardizzone S, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation without CD34+ cell selection in refractory Crohn’s disease. Gut 2008;57:1468–3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hasselblatt P, Drognitz K, Potthoff K, et al. Remission of refractory Crohn’s disease by high-dose cyclophosphamide and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36:723–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oyama Y, Craig Rm, Traynor AE, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with refractory Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2005;118:552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lopez-Garcia A, Rovira M, Jauregui-Amezaga A, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for refractory Crohn’s disease: efficacy in a single-centre cohort. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruiz MA, Kaiser RL Jr, de Quadros LG, et al. Low toxicity and favorable clinical and quality of life impact after non-myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant in Crohn’s disease. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hawkey CJ, Allez M, Clark MM, et al. Autologous hematopoetic stem cell transplantation for refractory Crohn disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:2524–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindsay JO, Allez M, Clark M, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation in treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease: an analysis of pooled data from the ASTIC trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn’s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jauregui-Amezaga A, Rovira M, Marin P, et al. Improving safety of autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut 2016;65:1452–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farge D, Labopin M, Tyndall A, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: an observational study on 12 years’ experience from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Working Party on Autoimmune Diseases. Haematologica 2010;95:284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snowden JA, Panés J, Alexander T, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation [AHSCT] in severe Crohn’s disease: a review on behalf of ECCO and EBMT. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:476–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daikeler T, Labopin M, Di Gioia M, et al. Secondary autoimmune diseases occurring after HSCT for an autoimmune disease: a retrospective study of the EBMT Autoimmune Disease Working Party. Blood 2011;118:1693–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kelsey PJ, Oliveira MC, Badoglio M, Sharrack B, Farge D, Snowden JA. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in autoimmune diseases: from basic science to clinical practice. Curr Res Transl Med 2016;64:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clerici M, Cassinotti A, Onida F, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of unselected haematopoietic stem cells autotransplantation in refractory Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 2005;19:5a–36a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.