Abstract

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–76), Chairman Mao fundamentally reformed medicine so that rural people received medical care. His new medical model has been variously characterised as: revolutionary Maoist medicine, a revitalised form of Chinese medicine; and the final conquest by Western medicine. This paper finds that instead of Mao’s vision of a new ‘revolutionary medicine’, there was a new medical synthesis that drew from the Maoist ideal and Western and Chinese traditions, but fundamentally differed from all of them. Maoist medicine’s ultimate aim was doctors as peasant carers. However, rural people and local governments valued treatment expertise, causing divergence from this ideal. As a result, Western and elite Chinese medical doctors sent to the countryside for rehabilitation were preferable to barefoot doctors and received rural support. Initially Western-trained physicians belittled elite Chinese doctors, and both looked down on barefoot doctors and indigenous herbalists and acupuncturists. However, the levelling effect of terrible rural conditions made these diverse conceptions of the doctor closer during the Cultural Revolution. Thus, urban doctors and rural medical practitioners developed a symbiotic relationship: barefoot doctors provided political protection and local knowledge for urban doctors; urban doctors’ provided expertise and a medical apprenticeship for barefoot doctors; and both counted on the local medical knowledge of indigenous healers. This fragile conceptual nexus had fallen apart by the end of the Maoist era (1976), but the evidence of new medical syntheses shows the diverse range of alliances that become possible under the rubric of ‘revolutionary medicine’.

Keywords: China, Cultural Revolution, Revolutionary medicine, Doctors, Barefoot doctors, Medical synthesis

It was 1970, the height of the Cultural Revolution, and Chairman Mao’s doctor, Li Zhisui, had just gotten in trouble with the boss. Mao suggested rusticating in the countryside to ‘really serve the people, …[and] get some education from the poor peasants’. Mao anticipated that the peasants would attack him as a ‘bourgeois remnant’, reaffirming Dr Li’s subordinate, even degraded, status in the revolutionary hierarchy. Instead, the villagers welcomed his team with open arms and were ‘happy to see us’. Because the villagers were in a rural county, ‘news from the outside rarely reached’ them, even at the height of the Cultural Revolution. For these villagers, class category proved to be insignificant relative to the medical expertise of the professionals. As Dr Li explained, ‘Whatever help we could give was always better than anything they had received before.’ 1

The Cultural Revolution (1966–76) is justly famous for the government’s effort to transform rural public health. Cultural Revolution methods, particularly barefoot doctors, fascinated international health policy makers and strongly influenced the WHO declaration on Primary Health Care in 1978 at Alma Ata, one of the key landmarks in global public health. However, scholars have reached widely different conclusions about the nature of China’s rural medical practice during the Cultural Revolution. Initially, some researchers, concurring with the Chinese government’s own assessment, believed that the Cultural Revolution was the highpoint of integrating Chinese and Western medicine into a new revolutionary form, noting that previously denigrated Chinese medicine had been revitalised. As Dr Field put it, ‘The resurrection, enthronement, and official support of traditional Chinese medicine constitute one of the more intriguing developments in medicine in the People’s Republic.’ 2 Newer scholarship, such as that by Fang Xiaoping, asserts that the Cultural Revolution actually ‘pitted Chinese and Western medicine against each other’ such that ‘Western medicine effectively won the battle, while Chinese medicine was steadily marginalised….’ 3 This paper suggests that while medical practices during the Cultural Revolution incorporated all three traditions (Western, Chinese and revolutionary), none of them ended up superseding the other. Instead, in rural areas these traditions were synthesised into a new type of revolutionary medicine in which rural practitioners were moving towards a professional identity, rather than the peasant-doctor identity prescribed by the state’s conception of revolutionary medicine. In addition, unlike earlier scholarship, which focused almost exclusively on barefoot doctors and the new phenomenon of mass medicine, this paper explores the hidden role that expertise played in making the system function.

The disparate understandings of medicine during the Cultural Revolution probably reflect the difficulty of finding credible sources. Earlier scholars (1970s) had access only to government propaganda while visiting medical delegations viewed only model sites, leading their scholarship to replicate the government version of revolutionary medicine. It was this medical model that they disseminated to the World Health Organization. Since archives opened, there have been almost no full length monographs on rural Maoist medicine. 4 Unfortunately, while archives shed light on earlier, less politicised periods during the Maoist era, during the Cultural Revolution, bottom-level campaign reports devolve to extensive quotes from Mao and large numbers of greatly exaggerated statistics, making them of somewhat limited utility. Likewise, oral histories can involve government intervention, censorship within the interview process and danger for the participants.

This exploratory paper partially circumvents these issues by piecing together four types of sources. The government’s mandated vision of revolutionary medicine is determined from newspapers, government documents, and most importantly, speeches from Mao. How and why grassroots medical practices differ from government mandates over time is ascertained from archives prior to the Cultural Revolution drawn from three famous health campaigns (patriotic health, schistosomiasis, and four pests) and several case studies: Jiangsu and Jiangxi Provinces (rural areas), Yujiang County (a backwater county in Jiangxi Province), Shanghai (one of the most advanced cities in China), and Qingpu (a Shanghai suburb that was originally a county in neighbouring Jiangsu province). 5 To determine where practice at model sites deviates from government propaganda, it uses published eyewitness reports from Western medical delegations with candid comments on discrepancies. Finally, the paper is dependent on extensive memoirs and oral history accounts in both English and Chinese from elite Chinese, Western and barefoot doctors posted to many parts of the country who can retrospectively report more openly on their experiences during the Cultural Revolution.

These sources make clear that each region created a unique medical synthesis depending on the availability of particular medicines, medical infrastructure and medical practitioners, but that there are common trends in how and why rural practice diverged from state mandates. This paper elucidates these trends and delves into the new types of practices that arose in the countryside. The paper will first sketch out the medical terrain prior to the Cultural Revolution, then examine the government’s revolutionary medical ideal and why rural people and local cadres were able and willing to alter this mandate; finally, it will assess the practices and identities that developed as part of the new medicine in the hinterland.

1. The Chinese Medical Scene prior to the Cultural Revolution

Prior to the Cultural Revolution, Chinese medicine stemmed both from elite traditions and indigenous rural traditions. By late imperial times, elite Chinese doctors based their medical practice on classical medicine tomes and their training on a highly respected master doctor, often a family member. 6 After a lengthy apprenticeship when they gained expertise in the complicated theory of Chinese medicine, physical diagnostic skills, and complex prescriptions uniquely shaped to each patient, they joined their teacher’s medical lineage, where they ministered almost exclusively to elites and wealthy merchants. Despite sharing an elite, literate tradition and a pejorative view of folk healers, neither these doctors, nor what we now term ‘traditional Chinese medicine’ had a unified field of theory or practice (See Figure 1). 7 Rural people usually employed a wide variety of indigenous practitioners, often simultaneously, including: Buddhist and Daoist clerics, spirit-mediums, fortune tellers, witch doctors, acupuncturists, bone-setters, illiterate local herbalists, and midwives. 8 A number of rural practitioners acted like elite doctors by wearing literati robes and mimicking their practices. Some did come from credible rural medical lineages, but many others were considered quacks by other physicians and patients alike. Rural people, noting their expense and low cure rates, used them as a last resort. 9

Figure 1:

In the past, elite Chinese medical doctors mainly treated urban and wealthy clients. Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome L0004700. Licenced under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

Western medicine was introduced to China by medical missionaries from many countries, who brought different variants of Western medicine, as well as aspects of traditional Western medicine (that is, ideas influenced by miasmas and humours). It was also introduced by Chinese students studying Western medicine in Japan. Before 1949, the extremely limited number of doctors of Western medicine practised predominately in big cities because urban areas contained the medical schools, hospitals, drugs, medical infrastructure, referral systems and wealthy patients needed for the system to function. In terms of rural areas, the Chinese state tried to establish one hospital in each county during the Republican era (1911–49) and wartime public health efforts (1937–45) occurred in rural south-west China near the provisional capital of Chongqing. Some medical missionaries also practised in rural areas. Despite these efforts, few rural people encountered Western medicine before the Maoist era. 10 From early on Western medicine was promoted by reformers as the only real, modern and scientific medicine, while Chinese medicine was denigrated as unscientific, superstitious and backward. 11 The newly trained cadre of Chinese Western doctors assumed these biases. They used their dominance of the first National Ministry of Health, started under the Nationalists in 1928, to try to eradicate their medical competition, resolving at the first National Board of Health Conference in February 1929 to abolish Chinese medicine. Despite government debate and protest by Chinese medicine practitioners, the Ministry passed a licensing regime in 1930 that required Western medical knowledge and graduation from a medical school of Western medicine, leaving practitioners of Chinese medicine in ‘legal limbo’. 12 Their ambiguous position was made worse because some of China’s most famous political reformers, including Liang Qichao, Kang Youwei, Sun Yatsen, Lu Xun, and Guo Moruo focused on Western-style health care’s political role in building a strong nation and a strong race. 13 State promotion of Western medicine was less about an accurate assessment of its merit, and more about a political agenda that linked Western medicine to modernity, self-strengthening and political sovereignty. 14

Although unsuccessful at eradicating Chinese medicine, the 1929 resolution profoundly affected it. Sean Hsiang-lin Lei finds that, for the first time, Chinese medical practitioners were inspired to work together to develop a new, unified and scientised version of Chinese medicine, aligned with the state. Early efforts at modernising Chinese medicine resulted in new Chinese medicine schools and research institutes during the Republican Era (1911–49). 15 This early work paved the way for the more comprehensive make-over during the Maoist period (1949–76), but never persuaded most Western doctors that Chinese medicine was a legitimate enterprise.

While living in the Shaanxi–Gansu–Ningxia Border Region in the 1940s, Mao came to a very different conclusion about the relative merits of Chinese and Western medicine based on practicality and population size. Mao observed that by the late 1940s China had over 540 million people and about 51 000 Western doctors who could only function with expensive, lengthy training and costly drugs and equipment, mostly produced outside China. As Mao explained earlier in a 30 October 1944 speech, ‘To rely solely on modern doctors is no solution.’ 16 By 1955, there were 70 000 Western doctors and 360 000 Chinese medical practitioners. If the government truly wanted to provide affordable medical care, it had better depend on this relative multitude of rural practitioners who only required inexpensive local herbs and a set of needles. 17 By the early 1950s, Mao added patriotism to practicality by deciding that Chinese medicine embodied a unique heritage, an idea Chinese medicine practitioners had been pushing since the late 1920s. Mao felt that once Chinese medicine was re-organised and tested according to scientific methods, it would not only enrich the field of medicine, but also facilitate China’s claims to be globally competitive in science. 18

As a result, starting from 1950 at the First National Health Conference and increasing significantly in the mid-fifties, the new Ministry of Public Health was mandated to promote co-operation between Chinese and Western doctors. 19 Despite growing government pressure, most Western physicians remained convinced of their medical model’s superiority. According to early Jiangsu Province health campaign reports, even during rural health campaigns, which suffered from insufficient health personnel, Western doctors ‘look down on [Chinese practitioners] and not only don’t help them, but also actively create barriers to their work’. 20

By 1965, Mao was extremely frustrated by the unwillingness of the Western medical establishment to incorporate either affordable Chinese medicines or ideologically based Party guidelines into their practice. Most Western doctors, fearful of medical malpractice, insisted on practising medicine based on normative practices and proven drug regimens, making rapid expansion of rural care almost impossible. Mao’s fury was backed by concrete numbers. As of 1965, of the 1.5 million Western medicine professionals, 70% worked in the cities, 20% in county seats, and only 10% in rural areas where the majority of the population resided. In addition, rural areas only received 25% of national medical expenditure; the other 75% went to the cities. 21 The elite Chinese medical establishment also retained its traditional focus on urban elites. For change to occur, something had to pulverise the basis of both types of medicine.

2. The Dream: Remaking Medicine as a Revolutionary Force

Mao was happy to supply the necessary hammer. In 1965, he issued the June 26 Directive excoriating the Western medical establishment’s urban focus and its lengthy, book-oriented training methods. 22 Even as Mao was verbally promoting Chinese medicine, he also launched an even more extreme assault against the elite Chinese medical establishment (discussed below). Similar directives had been issued in the mid-fifties, but earlier Mao lacked the power to disrupt the medical profession’s practice, training and organization. 23 Once the Sino-Soviet split occurred in 1960, Soviet medical experts in China departed taking their technocratic focus with them. This left nothing to mitigate Mao’s populist version of Marxist medical practice. Freed from global medical norms, Mao replaced specialists with ‘red and expert’ members of the masses. 24 By the time of the Cultural Revolution, these trends, coupled with the association of the medical profession with Mao’s political rival Liu Shaoqi, gave Mao enough authority to remove high-level leaders in the Health Ministry, alter medical training practices, gut the urban medical establishment and force it to switch its focus to the countryside. 25

Mao brought medical care to the countryside with a number of practical changes to the pre-existing medical structure. First, he forced about one-third of Western doctors and elite Chinese medical practitioners from both the civilian and the military medical systems to serve in the countryside, initially as rotating medical teams, and later, after 1970, as permanently rusticated doctors. Doctors at all levels participated in this mandate: from top urban physicians to bottom-level doctors in commune hospitals, all were sent down to the villages. The most senior doctors were more likely to receive a ‘Rightist label’, and experience strong government coercion to stay for lengthy periods in rural areas to be re-educated by the peasants. 26 Urban doctors were a large subsidy to the rural medical system: they brought medical knowledge and skills, but their travel expenses and salary were paid by their originating institutions. 27 In addition, the government dramatically shortened and altered medical school training for both Chinese and Western medicine, while including political indoctrination, physical training and practical rural medical experience in the curriculum. This followed Mao’s June 26 Directive that attacked traditional medical education and concluded that, ‘the more books one reads the more stupid one gets’. Shorter training ensured a rapid expansion of medical talent all slated to serve in the countryside. 28

Starting in September 1968, the national government promoted the idea of rapidly trained and cheaply paid paramedics, called barefoot doctors, discussed below, who were supposed to make health care more affordable. Later, in December 1968, the government encouraged communes to establish co-operative medical services whose precarious funding base came from fees paid by commune members and brigades. 29 Finally, in 1970, the government started a massive national herbal medical campaign to encourage collecting, growing and processing local herbs into affordable medicines and forcibly gathering previously secret prescriptions of medical lineages that were then supposed to be disseminated to all. This campaign not only increased the availability of herbs, which had been in short supply, but also disseminated the message that using local herbs was patriotic and preferable to other options. Together these changes resulted in a large expansion of the rural medical system. Originally, there were county or district hospitals, and inferior commune hospitals; now commune hospitals were upgraded, and the system extended downward to include clinics at the production brigade level. 30 The result was access and affordable care to a degree unknown before.

The barefoot doctor programme, the most famous of these changes, became emblematic of the entire effort to transform rural public health. 31 Barefoot doctors were educated young people with some junior high school education, drawn from lower-middle peasants and selected by their community. They were supposed to receive three to twelve months of medical training, though many received much less, and then return home to practise. Ideally, initial training was supplemented with further classes or work under more experienced doctors. Training involved learning to identify and treat common diseases with Chinese herbs, some Western drugs, a limited number of acupuncture points and minor surgery. Barefoot doctors were supposed to collect, grow and process medicinal herbs, improve sanitation, educate villagers about hygiene and disease prevention, and take a leadership role in the public health and vaccination campaign of the moment. While statistics from the Cultural Revolution are always suspect, one study found that from 1969 to mid-1974 there were about 1.08 million barefoot doctors, creating a doctor/population ratio of 1 : 760, significantly better than the rural 1 : 8000 ratio prior to the Cultural Revolution. 32

Mao envisioned barefoot doctors at the centre of a new type of revolutionary medicine. 33 Practitioners would gain knowledge through practical experience, use local prescriptions and herbs that effectively indigenised medical practice, and focus on personalised care, motivated by a sense of altruistic brotherhood. These vanguard barefoot doctors would also create a new nexus of medical talent in the countryside, helping empower their rural communities. At the same time, theoretically oriented professional doctors and practices would wither away due to the ‘enlightenment’ provided by gruelling rural re-education. Mao’s dreams of creating this new revolutionary medicine regime seemed realistic: the Cultural Revolution was a pressure cooker that tended to force change; the values and ideas embedded in barefoot doctors and in revolutionary medicine were constantly reinforced by other non-health campaigns; and Mao had the power to destroy the pre-existing medical establishment.

3. The Dream Challenged: Opening a Space for Alternatives to Maoist Medicine

Mao’s medical agenda seemed beneficial for all except medical professionals. Yet, despite his best efforts, the all-pervasive Mao cult, and the intimidation and violence of the Cultural Revolution, this study finds that the parameters of his revolutionary medicine were radically altered in the countryside. How was this possible? It turned out that the major stakeholders, mid- and lower-level government officials, villagers, and doctors both old and new, found various aspects of Mao’s revolutionary medicine unsuitable for rural conditions and needs. Together, these groups created a space where new ideas about medical practice and identity could be developed that reflected neither elite Chinese or Western medicine, nor Mao’s new medicine. This section examines why these groups never fully followed Mao’s revolutionary vision.

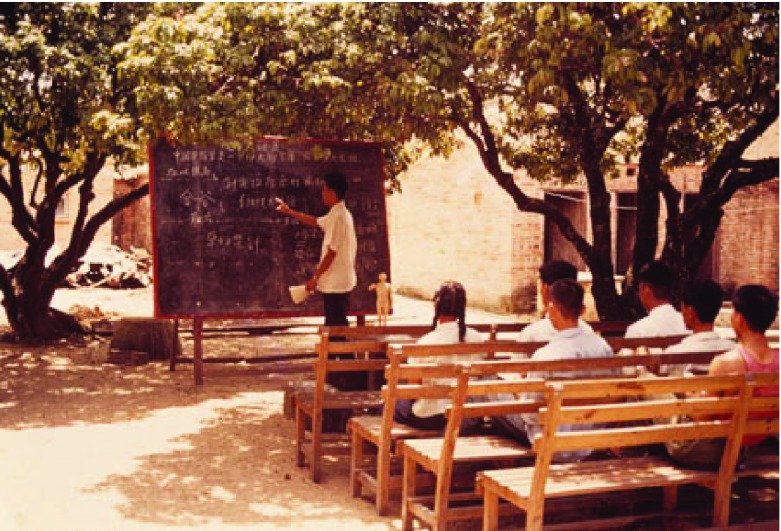

Most provincial-level governments had dutifully followed a weaker version of Mao’s medical mandates during the Great Leap Forward (1958–61) but discovered that ignoring the expertise of physicians and known medical guidelines about effective treatment regimens provided a short-term ideological victory but a long-term campaign loss that wasted scarce resources and political capital. Moreover, once provincial leaders had to collect statistics and report their successes in front of peers, it became politically dangerous to fail. In addition, cadres’ constant mutual visits to the multitude of model sites made it harder to completely falsify statistics and to conceal perfunctory participation. As a result, some provincial leaders quietly made structural adjustments and leadership choices that placed those with medical expertise in a position to alter campaign practice. During the early Cultural Revolution provincial activities were too transparent for central directives to be avoided and it was dangerous not to comply. Therefore, provinces sent urban medical personnel down to the countryside, shortened medical training, opened new short-course medical schools in counties, sponsored co-operative medical services and herbal medical campaigns, and generated barefoot doctors on a large scale. However, as the national government moved on to new mandates and the government and society increasingly decentralized, a space was created for rural provinces to quietly make their own decisions. Consequently, while highlighting areas of campaigns that made them seem like purely ideological victories, some mid-level cadres used medical professionals strategically (see Figure 2) and turned a blind eye when lower-level cadres similarly altered national mandates. 34

Figure 2:

The prominent barefoot doctor is in the front, but the less obvious Western doctor actually leads the way. Cai Zhixin ‘Zuo gongdi shang de jianbing’ [Act as a construction pioneer], Jiankang bao [Health news], 814, 1 (16 January 1960). Used with the permission of Chinese copyright law, Articles 21 and 22, (5).

Before the Cultural Revolution, leaders at the county level and below (township, commune, brigade and team) adhered closely to the national government’s line on medicine, which was easy to do because they sloughed off responsibility for health campaigns onto the local health department. However, during the Cultural Revolution, decentralisation and attacks on the bureaucracy made health campaigns their problem. Chaos at the top and the purging of many high-level Party leaders provided a space for county, commune, brigade and production team cadres to make up their own minds about how to run the campaign. As a barefoot doctor from Shanxi Province put it, ‘There were many [national] policies. However, after they were handed down, they weren’t all followed. When they reached the bottom they were spoiled.’ 35 Like the Provincial Government, rural cadres looked beyond Rightist labels, discovering that the vast numbers of urban doctors now in the countryside long term had much higher cure rates. Local leaders noticed that they maximised their political capital when sent-down doctors practised medicine, rather than labouring ineffectively in the fields. As some village leaders put it: ‘We can get anyone to shovel manure. We have to take our children to the commune clinic a full hour’s walk away and receive only haphazard treatment at that. You tell me – are you more important to us as a doctor or as a peasant like us?’ 36 Local cadres also realised that participation of professionals and technical experts increased the success rate of local mass health campaigns. As a secretary of a rural Jiangxi county put it, ‘All the technical people were sent to the countryside and gave us guidance. Because of this, the work was of high quality.’ 37 If cadres did not get into trouble for allowing urban doctors to practise medicine, they gradually moved them up the medical ladder from the brigade to the commune hospital, where they could more effectively employ their skills. 38 Thus, while publicly attacking elitist urban medicine and in-depth theoretical knowledge, cadres up and down the political hierarchy found well-trained physicians essential to their own success. As a result, they quietly provided support that allowed these battered doctors to maintain some degree of professional identity, even as the national government sought to strip them of their credentials.

Maoist revolutionary medicine should have had great appeal to villagers as it alleviated two of their biggest problems: cost and access. The combination of the co-operative medical services, barefoot doctors with low salaries, acupuncture and herbal medicine made rural medical care eminently affordable. Similarly, due to the vast expansion of medical personnel down to the new brigade-level clinics who were willing to make home visits, it was now possible to get medical help without losing time at work. However, having solved these two essential problems, pragmatic villagers now wanted treatment that worked. In contrast to Mao, they were unconcerned about class labels, ideology, indigenous pride or even whether the doctor came from the village. The main test of new physicians was effective treatment. For example, Ban Xiuwen, a famous Guangxi elite Chinese medical doctor and professor labelled a Rightist and sent to the countryside to be re-educated was ordered not to let villagers know his profession. However, ‘…doctors there were impossible to conceal. Over time they knew what I really did. At that time, there was a peasant with a very swollen knee…I couldn’t just stand idly by and ended up treating him. There was also a small child with a high fever’ whose ‘fever rapidly dropped …’ after treatment. From then on, people looking for a doctor and medicine came in an endless stream.’ 39

Villagers refused to forgo assessing medicine based on efficacy and cast doubt on the briefly trained middle schoolers’ medical skills, even as the government made repeated injunctions to give these ‘socialist new things’ (that is, the barefoot doctors) the benefit of the doubt lest ‘ill-wishers hiding in dark corners…[such as class enemies try] to make a laughing-stock of [them]’. 40 However, it soon became apparent that barefoot doctors were the perfect storm of malpractice. Their limited knowledge combined with minimal supervision led to frequent misdiagnoses. An oral history compendium of barefoot doctor accounts from all over China repeatedly indicated that their biggest problem was insufficient knowledge. As an older barefoot doctor from Shandong Province put it in hindsight, ‘My medical knowledge was limited. Even though I studied at the health school, when I tried to use it I always felt at a loss…. I bumped into some things where I was apparently right, but actually wrong.’ 41 An older Shanxi Province barefoot doctor who started practising medicine in the mid-sixties concurred, ‘At that time there were no standards. If you could wield two needles it was enough. Actually, previously I hadn’t received any real training. Only in 1978 did I attend a half-year of free training.’ 42 With few drugs to dispense and the most effective ones (that is, antibiotics) preferentially used by cadres and their families, barefoot doctors used what they had, irrespective of its treatment potential for the particular disease. Moreover, Western drugs produced in Chinese factories and local herbal medicines had poor quality control. Rural areas also often lacked supplies such as masks, gloves or autoclaves, making rural deliveries particularly fraught and infection control almost non-existent.

Finally, the empowerment of both patients and barefoot doctors led to devastating results. Patients took charge of the medical relationship, demanding drugs they liked or had seen being effective on a neighbour. Further, impoverished patients sometimes refused to go to expensive hospitals for care, even when barefoot doctors told them the medical problem was too complicated or dangerous for them to treat. Barefoot doctors tended to comply with patients’ demands even when they were counter-productive or dangerous to their health because ‘If you did not satisfy them, they complained that you had treated them badly.’ 43 At the same time, empowered barefoot doctors, fortified by revolutionary prowess, government slogans and belief in Mao Zedong Thought, began treating complicated diseases, rather than referring them up the medical ladder to more experienced professionals. 44 As one former barefoot doctor put it, my ‘skills were pretty much limited to applying mercurochrome to whatever injury was presented to me…. [But] we were also allowed to do just about anything short of taking up a scalpel, though if you were brave enough, you could have a go at cutting someone open as well.’ 45 Emergency situations compounded this issue as villagers had no time to get to better hospitals. Moreover, local health departments were loathe to call problematic barefoot doctors to account, as they might get in trouble for not supporting Maoist medicine. 46

Instead of favouring revolutionary medicine, villagers supported professional expertise by voting with their feet. An urban doctor living in the countryside noted, ‘Villagers didn’t seem to trust [their barefoot doctor]…During his three months of training, he had learned to use three prescriptions to treat the patients. When he used up his three formulas without seeing any effects, he would run out of ideas….Villagers were afraid to see him because his acupuncture caused more pain than the illnesses themselves.’ 47 One villager summed it up by saying barefoot doctors were ‘idlers incapable of curing any diseases’. 48 In only a few years, rural people were complaining about barefoot doctors and sometimes bypassing them when they had serious diseases, going directly to professionals at the district or county hospital. 49

Western, elite Chinese and barefoot doctors helped undermine revolutionary medicine while simultaneously opening a space for something new. Each group had to move from the identity, practices and sense of the superiority of their own medical tradition to a position of openness and co-operation with the others. Barefoot doctors, as discussed in the next section, seemed to have every incentive to adhere to Mao’s vision of revolutionary medicine since their vanguard role placed them in leadership positions. However, despite Mao’s injunctions to dominate urban professionals and learn only from practical experience, many barefoot doctors came to appreciate, respect, support and even try to protect them. In terms of urban doctors, Mao had already tried to transform them by dispatching them to run short rural campaigns and receive re-education from the peasants during the Great Leap Forward (1959–61). 50 While this experience may have made them more sympathetic towards rural people, it neither persuaded physicians to dedicate themselves to rural medicine, nor made them willing to view Chinese doctors as equals and to work with them. 51

During the Cultural Revolution, three factors seem to have opened urban doctors to new medical possibilities: the concerted destruction of their profession, personal devastation experienced in the cities and long-term forced rustication in the countryside. Both Western and elite Chinese physicians spent the 1960s watching the state destroy their medical tradition. Mao demanded that Western medical training, the most crucial part of inculcating professional knowledge and identity, be severely truncated. 52 During the Cultural Revolution, class background, rather than educational achievement, determined entrée to medical school. These new medical students, mainly drawn from barefoot doctors with a junior high school education, had difficulty assimilating complex medical knowledge. 53 Simultaneously, the medical faculty came under intense scrutiny, making teaching a task freighted with great anxiety. As one doctor put it, ‘when you commit a blunder in teaching, someone will grab you by the hair and shoot you’. 54 Medical specialisation, a core way to define professional expertise and responsibility, was eliminated. The medical hierarchy was also overturned. Patients and medical professionals lower on the totem pole, such as nurses, were encouraged to demand power in decision-making. These changes upended the physician’s position as the apex of knowledge and power. In some mass health campaigns, the government even dictated revolutionary drug regimens based on ideological, rather than medical concerns, for example telescoping a four-week regimen into four hours in the name of production efficiency. 55 With the basis of their professional identity under attack, and minimal training of new doctors, many physicians found it difficult to determine who truly counted as a doctor. 56

The elite Chinese medical establishment faced an even stronger assault by the state. Deemed a feudal remnant with almost nothing to offer the new society, the government closed major Chinese medicine schools, stopped many medical journals, and attacked the theoretical basis and the diverse, pluralistic nature of this medical tradition, calling it superstition. Chinese doctors were encouraged to simplify and systematise their traditions and to assume the scientific frameworks, medical tools and anatomical systems of Western medicine. 57 Concomitantly, the ‘Four Olds’ campaign launching the Cultural Revolution obliterated some of the key mechanisms to teach and remember Chinese medicine and to instil its medical identity: irreplaceable ancient medical tomes were burned and family grave sites, lineage halls, and medical lineage genealogies were destroyed. 58 Far worse, an extraordinary percentage of elite elderly doctors, the true repositories of this tradition, were tortured and even killed. For example, in a book commemorating the lives of northeastern Jilin Province’s most famous elite Chinese physicians, twenty-nine (63%) of the biographies of the forty-six physicians alive during the Cultural Revolution mentioned that their experiences led to retirement, devastating illness and sometimes death. 59 The government also tried to destroy the master–disciple relationship that transmitted Chinese medicine. Apprentices were urged to attack their elderly teachers, leaving a long-term residue of distrust. As a result, from 1959 to 1977, the number of Chinese doctors declined from 361 000 to 240 000. 60 Finally, the government intervened to an extraordinary extent in treatment methods and laid out the Chinese medical establishment’s complete research agenda. Many Chinese medical doctors felt that their medical tradition was adrift, requiring fundamental transformation for it to survive in the new society. 61

Devastating attacks, torture and imprisonment of Western and Chinese medical doctors in the city provoked a new attitude of open-mindedness among the professional medical community. For those lower on the medical hierarchy, the Cultural Revolution combined endless stretches of boredom with short stints of total terror. 62 For top doctors, being a janitor and shovelling coal in the hospitals they had directed, along with years of being screamed at, beaten and tortured in the ‘cowshed’, made the formerly abjured countryside seem like a heavenly alternative. 63

Long-term rustication in the countryside was the final transformative element. Doctors were not given a choice about being sent to the countryside; most were not happy about going, and some continued to experience abuse while there. However, many found that the pressure in the countryside was much less than in the cities. They were struck by the gratitude of villagers for professional competence, especially after spending years being beaten for their skills. As Dr Chung explained, his time in the countryside was the ‘most enjoyable period of my rehabilitation. After the years of confinement with the attendant physical and mental harassment, it was a good feeling to be useful again, confident in my ability to help others.’ 64 In the short-term rural stays during the Great Leap, doctors looked at the terrible conditions, and the lack of sanitation, infection control, pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, and engaged only minimally. Long-term, possibly permanent stays meant these problems had to be faced as their new status quo, opening doctors to alterations in practice and identity they would never have considered before. Similarly, isolated rural locations combined with the chaos of the Cultural Revolution meant lower-level government (especially county-level and below) and villagers were able to quietly jettison parts of Mao’s revolutionary medicine. Instead, they collectively constructed an alternative revolutionary medicine that truly suited rural conditions, local stakeholders and newly receptive urban doctors.

4. The Dream Remade: The New Revolutionary Medicine of the Countryside

The new rural medicine developed in a piecemeal way dependent on the available doctors. It matched neither Mao’s notion of revolutionary medicine, nor Western medicine, elite Chinese medicine, nor some admixture. Instead, transmission of knowledge, medical practice, relationships between medical providers and the resultant professional identities reflected a new medical fusion. This new fusion depended on rural isolation and ideological domination by the government of the professional medical establishments. Rather than barefoot doctors as the state’s primary representatives, with ideology and practical medical know-how determining practice, this new synthesis was based on a medical community that retained its original specialisations and pooled expertise to meet the true needs of the villagers (see Table 1). By the time of the Reform era (1976–present), the fragile conceptual nexus created by the contingencies of the Cultural Revolution had fallen apart.

Table 1:

Comparison of different medical traditions to the new revolutionary medicine.

| Elite Chin. Med | West. Med | Mao’s Rev. Med | Actual Rev. Med | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basis of medicine | Knowledge | Knowledge | Will  ideology ideology |

Knowledge |

| Knowledge transmission | Lengthy master-disciple  systematised knowledge systematised knowledge |

Lengthy classroom, preceptorship  systematised knowledge systematised knowledge |

Brief class, mainly practice  unsystematised knowledge unsystematised knowledge |

Brief class, master-disciple/preceptor, practice  unsystematised knowledge unsystematised knowledge |

| Medical Practice: basic stance and response to the unknown | Generalist. Innovate within tradition and consult with head of medical lineage | Specialist. Implement newest protocol vetted by experts and referral | Generalist. Constantly innovate practice based on current conditions (indigenisation) | Specialist and collaborating specialists. Innovate in and beyond own tradition helped by other specialists |

| Medical community | Very hierarchical | Hierarchical | Hierarchical (prior bottom on top) | Less hierarchical, more collaborative |

| Professional identity | Member of a medical lineage | Accredited physician | Peasant engaged in altruistic brotherhood via personalised care | Caring healer |

4.1. Knowledge transmission

After repeatedly attacking China’s urban medical establishment, Mao proposed a clear solution: ‘Medical education should be reformed. There’s no need to read so many books.’ This prescription was not just about lengthy medical training, but meshed with Mao’s broader concern of how knowledge should be produced and employed: ‘Knowledge begins with practice, and theoretical knowledge is acquired through practice and must then return to practice.’ He felt that abstract knowledge, a defining characteristic of many professions, separated experts from the masses and caused them to focus on abstruse theoretical issues at the expense of real world problems. 65 Therefore, barefoot doctor training programmes intentionally focused on simplified practical knowledge so that abstract, systematised knowledge would not develop. However, the outcomes undermined Mao’s goals. Thousands of simple factoids were hard to retain without the mental map provided by the systematisation of knowledge. Once training was over, practical experience without a wider medical framework made every medical encounter a process of trial and error using rural people as test subjects. It was hard to apply data points to the complex mutually interacting system presented by the human body and difficult to learn from its varied responses to diseases and drugs. The result was that the assimilation of knowledge from practice appears to have been quite slow. 66

Lack of systemised knowledge made barefoot doctors heavily dependent on outside sources of expertise, rather than free from them. They describe themselves as constantly flipping through manuals in front of patients to figure out their illnesses, a spectacle that did not increase patients’ trust in these ‘socialist new things’. 67 As a barefoot doctor from Yunnan Province put it, ‘half the time I did the work and half the time I fumbled along reading my book and trying to gain enough knowledge to be able to practise.’ 68 Ironically, by attempting to eradicate bookish knowledge, Mao created a system where practitioners were even more reliant on it. Likewise, by eliminating systematised knowledge, barefoot doctors were unable to develop diagnostic intuition, making them dependent on their teacher’s guidance and unable to act independently. As a result, although Mao attacked the master-disciple hierarchical model of elite Chinese medicine, it not only continued but expanded in scope. Barefoot doctors lucky enough to have nearby professionals, eagerly sought them out for frequent consults and tried to develop an ongoing relationship as a preceptee. For example, when ‘Dr’ Xiong, a famous Jiangxi Province farmer who became a surgeon after brief training operated, his teacher Dr Zhu was his ‘assistant’. As Dr Xiong put it ‘the presence of Dr Zhu and two other doctors…increased my confidence…and gave us guidance.’ 69 Similarly, when Jiangxi barefoot doctor Mao Zhixiao encountered a challenging patient, he would run to Dr Han Songling, nominally under his direction, to ‘beg him to specially treat the patient’. 70 As Dr Yao, a Shandong Province barefoot doctor explained, ‘When Rightists [doctors] were sent down to the countryside, I learned quite a bit of knowledge from them by their side.’ 71 Lack of expertise reaffirmed professional barriers, rather than broke them down, and ensured that barefoot doctors occupied a permanently subservient position in the medical hierarchy. 72

4.2. Medical practice

Revolutionary medical practice was supposed to promote indigenisation, practical know-how and innovation. Mao hoped that depending solely on local herbs, personnel and knowledge would engender self-reliance and uplift. In fact, rather than being driven by belief in revolutionary medicine, the decision to use local herbs and acupuncture supplemented by a few cheap Western and Chinese ready-made drugs as the primary rural treatments was driven by insufficient production of drugs, factory disruption, poor supply chains and expense. 73 Rural people were well aware that better Western pharmaceuticals and Chinese medical compounds existed but were unavailable in the countryside. In fact, their quest for these more expensive, and more effective, drugs threatened to destroy the co-operative medical services. 74 Forced indigenisation tended to lead to rural frustration, rather than empowerment.

Although some scholars have suggested that the use of herbs and acupuncture led to the revitalisation of Chinese medicine, the new rural practice was distinctly different from the elite tradition. 75 The whole theoretical diagnostic system was almost entirely replaced by gathering experiential knowledge to see what worked. 76 In addition, elite medicine’s complex multi-drug prescriptions with herbs from Sichuan, Yunnan and Hunan were replaced with single local herbs, many newly identified or stemming from local herbalists. 77 Finally, elite medicine stopped using acupuncture in the mid-1700s because it was ‘vulgar’, whereas revolutionary medicine revitalised acupuncture, discovered large numbers of new points, and used novel and dangerous methods involving deeper insertion and low electric currents that had not been part of the tradition before. 78

Revolutionary rural medicine, which appeared to successfully employ practical know-how, was actually dependent on expertise. 79 Western and elite Chinese medical experts provided a constant infusion of urban medical knowledge via visiting medical groups, initial training of barefoot doctors, and long-term rusticated physicians who treated complicated diseases and acted as preceptors for their newly fledged peers. Local expertise was also essential. Local doctors, herbalists, bone-setters and acupuncturists, many of whom had undergone lengthy apprenticeships, had to train barefoot doctors in each technique and act as their preceptors for them to be successful. While such local practitioners, often illiterate, were not generally recognised as experts, this new rural medicine would have accomplished little without their expertise. Knowledge of how to identify, grow and process diverse herbs was not just common sense. Without local herbalists, few barefoot doctors, even those with plant guides, were initially successful at finding and identifying medicinal herbs in the nooks and crannies of the mountainside. 80 Although barefoot doctors were lauded for their gardens, local experts often actually carried out the ‘technical aspects’ of gardening and herb collection, while barefoot doctors ‘simply followed them’. 81 A barefoot doctor commented that these things ‘really couldn’t be accomplished by a layman who hadn’t undergone a systematic acquisition of knowledge’. Even though he tried his hardest and consulted many books, ‘most everything died. Freshly gathered medicinal herbs…became mouldy.’ 82 Compelling rural Chinese doctors to share secret prescriptions did not mean barefoot doctors knew how and when to use them. Forced to deal with dismal access to both Western medicines and the herbal pharmacopeia of classical Chinese medicine, many professional Western and elite Chinese doctors also became interested in learning herb lore and acupuncture points from local experts. 83 Finally, the significant minority of barefoot doctors drawn from pre-existing expert local health providers supplied another source of hidden knowledge to the new rural medicine. 84

Ironically, even as the national government trumpeted the combined successes of ideology and practical know-how, people and places identified as ‘models of revolutionary medicine’ often succeeded due to an abundance of their own and others’ professional expertise. When national model barefoot doctor Sun Lizhe was asked to speak about her work at a national conference, her original draft was edited to reflect her dedication to Mao as the basis for achieving her goals. Unhappy about lying, she knew it was her medical knowledge and technical expertise that led her to success. 85 In model sites, this expertise was frequently provided by hidden subsidies from provincial governments, a quiet acknowledgment that excellent medical systems could not function without them. For example, the famous national model Dazhai’s clinic was bigger, better equipped, had more fully trained doctors and other medical personnel, and had barefoot doctors who received significantly longer training than was the norm. 86

Medical innovation and experimentation to overcome insufficient resources, the last core element of revolutionary medical practice, was valorised as an opportunity for rural ingenuity. Local inventiveness played a key role, but mostly to offset physical deficits, such as repurposing decrepit temples as clinical spaces and doors as beds and operating tables. Once again the limited, un-systematised knowledge of barefoot doctors made it difficult for them to innovate medically. In contrast, urban doctors and expert local herbalists and acupuncturists were much more capable at substituting medicines or local herbs, altering growing conditions so plants survived, and making educated guesses about new acupuncture points than barefoot doctors. The needs of desperate patients, rather than faith in the Party and Mao Zedong Thought provided the greater push for innovation. 87 The deep, systematised knowledge base of local herbalists and urban doctors supplied the means to innovate and compensated for the dearth of resources. In the end, within the new spaces provided by revolutionary medicine, each type of medical provider seems to have depended on the non-overlapping innovative capacity of the others.

4.3. Medical community

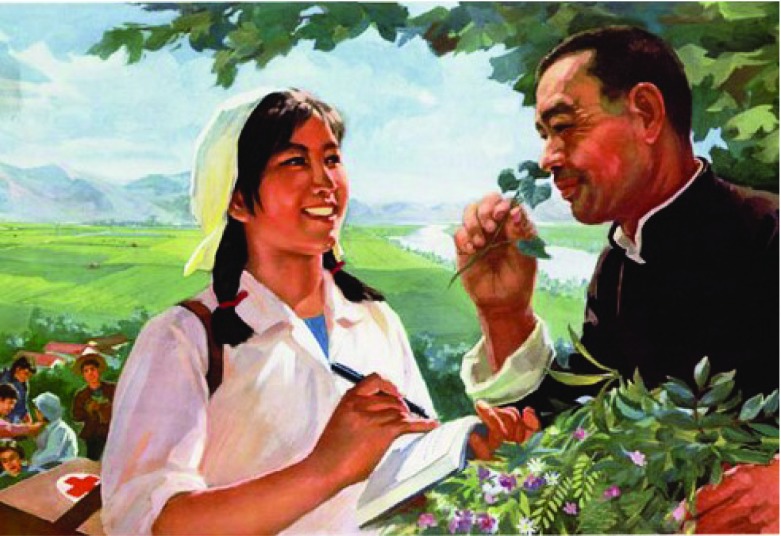

Despite government injunctions claiming the superiority of barefoot doctors, actual rural medicine reflected a complex mutually dependent medical community where urban and rural doctors had different domains of power. 88 As the politically correct representatives of Mao’s new medicine, barefoot doctors were supposed to dominate their despised urban peers. However, as many barefoot doctors were trained by urban doctors, their teacher–student relationship helped establish a respectful attitude (see Figures 3 and 4). Newly fledged people’s doctors did not want to see family and fellow villagers die because of malpractice or lack of knowledge. Rusticated urban youth who became barefoot doctors might not view villagers as family, but their position was precarious and they did not want to get in trouble for negligence. It also became clear that ideology and belief in Mao were not enough to magically heal people or conquer physiology. Surgery using acupuncture anaesthesia was an especially stark example. Many rural acupuncturists engaged in this revolutionarily anointed branch of medicine had more skill in Mao quotes than in finding acupuncture points. The result was excruciating for both patient and neophyte surgeon, providing a clear example of when ideology was not enough. 89 Even though barefoot doctors were in leadership positions, and sometimes responsible for carrying out anti-Rightist campaigns against urban doctors, they tended to be grateful for their help, appreciative of their professional expertise, and willing to learn both the medical knowledge and the professional identity that their new medicine was supposed to replace. Some barefoot doctors even used their extensive local connections and the political power of being young lower-middle peasants to protect urban doctors from the savage politics of the time. 90

Figure 3:

Barefoot doctors learning from Western doctors helped instil respect. ‘Students studying to become barefoot doctors, China, 1972’, Photo from the collection of Jeoffry B. Gordon, MD, MPH. Used with the permission of Jeoffry B. Gordon.

Figure 4:

Barefoot doctors learning from traditional Chinese doctors helped instil respect. ‘Barefoot Doctors’, Chineseposters.net (accessed 7 July 2015). http://chineseposters.net/posters/e13-659.php. Used with the permission of Chineseposters.net.

Western and elite Chinese doctors were equally interested in fostering a supportive medical community. Western physicians originally looked down on elite Chinese doctors, and both groups derided barefoot doctors and pre-existing rural herbalists and acupuncturists. However, horrible harassment in the cities, the prospect of long-term rustication, and the fact that local herbalists were the only ones knowledgeable about the most accessible drugs meant urban doctors were determined to get along with these previously despised groups and find ways to work together. 91 In addition, because of their Rightist label, many urban doctors were in a dangerous position in the countryside and perfectly positioned to become scapegoats if anyone died or if medical campaigns failed. 92 As a result, many urban doctors were heavily dependent on the barefoot doctors to provide them with the necessities of life, to parlay their advice about realistic medical practice, and to supply the respectable political evaluations needed to stay out of trouble. Any perceived gap or clique among the different types of medical providers could be exploited, but a unified face and a history of successful campaigns and cured villagers would bring respect to all. Thus, the best way to gain barefoot doctors’ support was to freely contribute medical expertise, quietly teaching and thereby buttressing the reputation of their rural peers. Even though the Party tried to create schisms to ensure barefoot doctors dominated the rural medical community, the frightening revolutionary environment for the urban doctors and the alarmingly limited medical knowledge of the barefoot doctors generally ensured that they formed a mutually supportive medical community.

4.4. Professional identity

Mao purposely tried to destroy the professional identity of Western and elite Chinese medical practitioners, because their abstract knowledge and expertise allegedly alienated them from the people and made it impossible for them to care for the masses. 93 He replaced their professional identity with a new identity based on being a carer, that is doing nursing care, and on altruistic brotherhood, that is engaging in unlimited work for a low salary based on a shared identification as fellow peasants. Mao had mixed success in instituting this new identity for either professional or barefoot doctors. The model of carer doctors equal in stature to clients was incompatible with the actual ideas of rural people. Rural people respected urban doctors, particularly older ones, not only because of their cure rates, but also because they fitted the villagers’ criteria for knowledgeable, venerated elders. It was socially inappropriate for such people to undertake carer’s duties, as such duties were associated with young women at the bottom of the family hierarchy. Precisely because of their age and their lofty position in the hierarchy of knowledge and specialised expertise, rural people felt confident about the ability of experienced doctors to help them, and secure in assuming a subordinate and compliant position as a patient. 94 Rather than impeding care, the doctors’ expertise provided the sort of care rural people most desired.

Doctors reacted differently to this new identity. Unlike the government, they also differentiated being a carer or nursing from caring or empathy. Few experienced urban doctors, most of whom were men, became intimate care providers, but they did change how much they cared. There was nothing like spending a couple years observing people’s horrific conditions, and occasionally sharing a full kang and an empty cupboard, to spark a profound sympathy. 95 Often trained to see patients as a mechanism that needed repair, doctors began to form close patient relationships, particularly when they discovered that, unlike in the cities, their medical expertise was received with unending gratitude. 96

The experience of practising medicine in the countryside and interacting with other types of physicians simultaneously altered and fortified urban doctors’ previous professional identity. The loss of the accoutrements of professional medicine including a full herbal pharmacopeia, sophisticated drugs, medical apparatus, sanitised spaces, laboratory testing facilities and an extensive referral system of specialists should have severely curtailed medical practice. Instead, revolutionary pressure, demands from villagers for help and long-term postings in rural areas with no hope of improvement pushed urban doctors beyond their previous professional boundaries. Medical innovation and risky procedures began to seem professionally appropriate, especially when treating villagers meant they did not have to suffer care by incompetent local medical practitioners. Urban doctors also realised that they could more fully inhabit their ideal role as professional doctors in the countryside. Unlike doctors trying to practise in the cities who faced frequent state intervention, doctors in the remote countryside report basing their decisions almost entirely on their medical training and professional knowledge and transmitting their professional expertise unfiltered. Finally, without the backup provided by lab tests or other equipment and referral systems, doctors found they were even more dependent on their own expertise in physical diagnosis. 97 For this reason, the need for extraordinary competence, knowledge and intuition was actually higher in rural areas. The ability to successfully identify and treat patients in these conditions became a point of professional pride for some doctors. 98 Ironically, personalised relationships with patients and their enormous gratitude reaffirmed urban doctors’ idealism about practising medicine, bringing them closer to the true spirit of barefoot doctors, while the need for expertise to counterbalance rural scarcity reinforced their appreciation of their own professional medical tradition. 99

Barefoot doctors and the minimally proficient ‘regular’ doctors trained during the Cultural Revolution constituted a spectrum of carer identities. Talented paramedics acted like expert urban doctors, demonstrating caring by dropping ideological rationales and focusing on becoming better clinicians with a sympathetic bedside manner. In contrast, some of the least knowledgeable and capable were happy to be reinforced by Mao Zedong Thought and pleased that although unable to identify or treat many diseases, they could excel at being carers. 100 In fact, based on this definition they could be better people’s doctors than their expert urban peers. In the long term, doctors buttressed by ideology, rather than knowledge, did not remain doctors as they could not retain patients. Many eventually returned to the fields. The few unskilled barefoot doctors who remained by the Reform era (1976–present) did not pass the exams instituted to assess expertise and were mainly unable to transition into their new identity as village doctors. 101

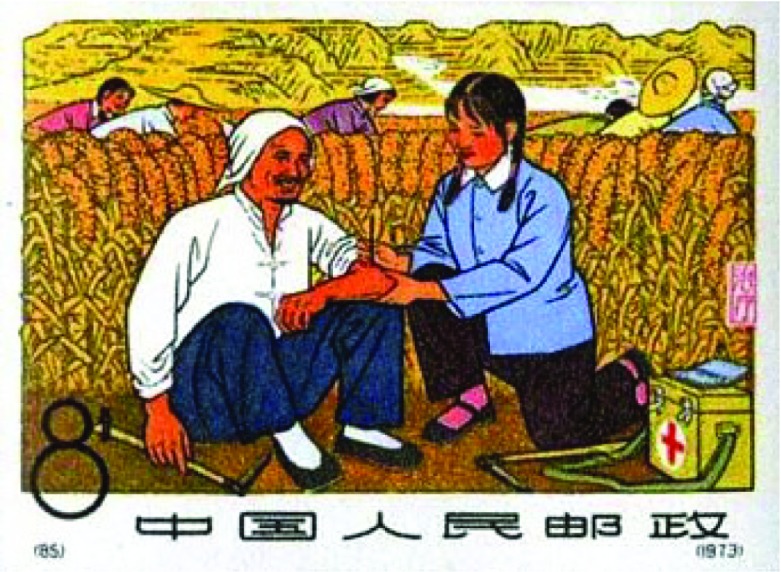

Altruistic brotherhood, the second aspect of the new medical identity, required barefoot doctors to retain a primary identity as peasants satisfied with a farmer’s salary (see Figure 5). This was amongst revolutionary medicine’s least successful aspects. Seemingly, barefoot doctors were paid with work points like any other villager. However, most peasants’ work points varied depending on their effort, whereas many barefoot doctors’ work points were manipulated to be on par with bottom-level Party Secretaries. 102 Additionally, they continued the denigrated strategy of traditional rural doctors of accepting gifts and using their deep village connections to acquire other life necessities. As a result, some were able to buy bicycles and watches, the ultimate consumer status symbols during the Cultural Revolution. 103 In contrast, because urban doctors’ salaries were supplied by their home institutions, and because of Rightist labels and terrifying experiences in the city, they neither received reimbursement from locals nor were generally confident enough to accept food or favours. Ironically, some elite doctors seem to have come much closer to embodying the selfless ideals of revolutionary medicine than many barefoot doctors. 104

Figure 5:

Barefoot doctors were supposed to retain a peasant identity, helping their fellow villagers with a spirit of altruistic brotherhood. ‘Barefoot Doctors’ 1974 stamp. Photo from the collection of Miriam Gross.

Few successful barefoot doctors retained a peasant identity. The discovery that successful treatment rather than ideological correctness was the way to win the support of the masses encouraged barefoot doctors to model themselves on the professional identity of urban doctors. The fact that they spent most of their time providing treatment, running vaccination and other prevention campaigns, and collecting, growing and processing medical herbs, meant that their interval in the communal fields often became a symbolic gesture. 105 This lived reality reinforced their participation in the community of doctors and distanced them from peasant life. Instead, they tried their best to serve the people by doing what the masses demanded, which contrary to Maoist goals, was to assume the guise of an autonomous professional doctor.

5. Conclusion

China stands as an exception among developing countries for making rural public health a primary domestic agenda. During the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government engaged in a broad-scale effort to transform rural public health as part of a larger project of rural uplift. Scholars of public health have variously characterised this endeavour as revitalising Chinese medicine or causing the ultimate predominance of Western medicine, while the CCP asserted that it created a new revolutionary medicine.

This study finds that that the Chinese government created the space for a new type of medicine loosely linked to all three medical prototypes, but ultimately different from all of them. It has previously been claimed that Western medicine was growing stronger during this period. Instead, this study finds that without drugs, equipment, referral systems, sterilised spaces, medical communities with their attendant hierarchies and knowledge transmission, normative professional Western medicine was unable to function. Elite Chinese medicine experienced an even more fundamental assault when the government tried to obliterate the basis of its medical theory; destroy venerated elderly doctors, the main repositories of the medical tradition; close schools and hospitals; extinguish famous medical lineages as well as master–disciple networks and the identities associated with them; and fundamentally alter the way Chinese doctors practised, including making most of their herbal armamentarium unavailable. In the end, revolutionary medicine did not succeed in its transformative goals, which included instituting new types of learning that gleaned knowledge experientially through practice, constructing a new type of medical practice centred on care, and fashioning a new medical identity that made practitioners indistinguishable from other peasants.

Mao’s ideas about revolutionary medicine assumed that the personal and the political had become almost entirely entwined. Ideally, knowledge, practice and motivation would be mutually reinforcing, transforming both individuals and their society. Instead, although ideology initially spurred changes, these changes were not maintained because they did not fit with rural realities or the personal goals and needs of the people. Rural people were unwilling to relinquish access to outside medicines or people that would cure them better. Similarly, Rightist or class labels and elitist professional hierarchies were irrelevant compared to finding somebody who knew how to make them well. Finally, being a carer – a symbolic stand-in for personalised state benevolence, did not match rural people’s own conception of the doctor as a venerated elder with access to arcane knowledge, especially since daughters-in-law and women more generally were already fulfilling and partially defined by the role of carer.

Villagers’ desires and rural realities, combined with the long-term interchange and mutual dependence of all doctors, seems to have reconfigured Mao’s revolutionary medical agenda. It soon became apparent that Mao Zedong Thought could neither substitute for insufficient economic or human resources, nor circumvent the complex physical realities of treating disease. Instead, the doctors realised that systematised knowledge and shared expertise were the only way to succeed. It was only by contributing their non-overlapping types of expertise and power that the whole medical community could thrive. Barefoot doctors supplied connections, political power, and detailed knowledge of local people, places and possessions; while Western doctors, elite Chinese doctors and indigenous herbalists and acupuncturists each provided different types of expertise. Only by forming a mutually respectful and supportive community and assuming a shared identity based on professional expertise could they partially compensate for the rural medical vacuum and survive the savage revolutionary politics that were trying to tear them apart.

Footnotes

Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao (New York: Random House, 1994), 521, 525–6.

Mark G. Field, ‘Health and the Polity: Communist China and Soviet Russia’, Studies in Comparative Communism, 7, 4 (Winter 1974), 423; Francesca Bray, ‘The Chinese experience’, in Roger Cooter and Jon Pickstone (eds), Companion to Medicine in the Twentieth Century (New York: Routledge, 2003), 730.

Fang Xiaoping, Barefoot Doctors and Western Medicine (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2012), 1, 12.

Fang, op. cit. (note 3) and Miriam Gross, Farewell to the God of Plague: Chairman Mao’s Campaign to Deworm China (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016) are among the only ones.

The patriotic health campaigns, which started in 1952 during the Korean War after an alleged germ warfare attack by the United States were China’s benchmark mass mobilisation public health campaigns, occurring at least once a year all over China. Their primary focus was on prevention, particularly sanitation, cleaning up and vaccinations. They often incorporated concurrent disease-specific campaigns such as those against schistosomiasis and the four pests. The latter attempted to eliminate flies, mosquitoes, rats and sparrows, and eventually many other pests.

For information on elite female doctors, see Furth. Charlotte Furth, A Flourishing Yin: Gender in China’s Medical History: 960–1665 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999), 266–300; Christopher Cullen, ‘Patients and Healers in Late Imperial China: Evidence from the Jinpingmei’, History of Science, 31 (1993), 100–1, 103; Sean Hsiang-lin Lei, Neither Donkey Nor Horse: Medicine in the Struggle over China’s Modernity (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 123, 131–2; Joshua Horn, Away with All Pests: An English Surgeon in People’s China: 1954–69 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969), 124.

Ibid. Throughout this paper I have chosen to use Chinese medicine, rather than traditional Chinese medicine. ‘Traditional’ Chinese medicine is a recent reconstruction of a diverse medical tradition that mainly occurred during the Maoist era. It incorporates ideas drawn from Western medicine, science and anatomy, discards aspects of the tradition that appear unscientific, and attempts to create a homogenised field of theory and practice. Because many indigenous rural healers had not yet absorbed the new Chinese ‘traditional’ medicine promoted by the state, I have dropped the word ‘traditional’ and simply refer to them as practitioners of Chinese medicine.

Arthur Kleinman, Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and Psychiatry (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1980), 62–8; Yu Laixi, zhonggong Yujiang xianwei xuefang lingdao xiaozu bangongshi [Yu Laixi, Schistosomiasis Prevention Leadership Small Group Office of Yujiang Party Committee of the CCP], Jiangxi sheng Yujiang xian xuefang zhi: 1953–80 [Jiangxi Yujiang County Gazetteer of Schistosomiasis Prevention: 1953–80] (Yujiang, 1984), 81.

Zhou Fukai, oral history compiled by Xiong Xiangsheng, ‘Yongyi mocai, jifu sangming’ [Quacks cheat them and the stepfather loses his life], in Liu Yurui and Wan Guohe (eds), Songwenshen jishi[Record of saying farewell to the god of plague] (Nanchang: Jiangxi Sheng zhengxie wenshi ziliao yanjiu weiyuanhui, 43, 1992), 69–72; Jiangxi Provincial Archive (JXA): X035-04-802, 1956.

Andrija Stampar and M.D. Grmek (ed.), Serving the Cause of Public Health: Selected Papers of Andrija Stampar, Andrija Stampar School of Health, Monograph Series, 3 (Zagreb: Andrija Stampar School of Health, 1966), 143, 144; Szeming Sze, China’s Health Problems (Washington DC: Chinese Medical Association, 1943), 13; Ka-Che Yip, Health and National Reconstruction in Nationalist China: The Development of Modern Health Services, 1928–37 (Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies, 1995), 108, 177, 190; Nicole Elizabeth Barnes and John R. Watt, ‘The influence of war on China’s modern health system’, in Bridie Andrews and Mary Brown Bullock (eds), Medical Transitions in Twentieth-Century China (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014), 227–43.

Early Western missionaries who practised traditional Western medicine, such as the Jesuits, appear to have been more open to a medical exchange with Chinese medicine practitioners. The Jesuits focused almost entirely on Chinese elites, trying to use medicine as a mechanism to convert the very top of society. Jonathan Spence, Emperor of China: Self-Portrait of K’ang-hsi (New York: Vintage Books, 1988), 91–112; Marta Hanson, ‘Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662–1722)’, Pacific Rim Report, 43 (July 2007), 1–10.

Yip, op. cit. (note 10), 59–60.

Bai Limin, ‘Children and the Survival of China: Liang Qichao on Education before the 1898 Reform’, Late Imperial China, 22, 2 (December 2001), 130, 140–1; Ralph Croizier, ‘Medicine and modernization in China: An historical overview’, in Arthur M. Kleinman et al. (eds), Medicine in Chinese Cultures (Washington DC: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, National Institute of Health (NIH), 1975), 26–7; David Lampton, The Politics of Medicine in China: The Policy Process, 1959–77 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1977), 9.

Bridie Andrews, The Making of Modern Chinese Medicine, 1850–1960 (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2014), 216.

This was the initial work to develop what we now call ‘traditional’ Chinese medicine, which peaked during the Maoist era. Lei, op. cit. (note 6), 97–119.

‘The United Front in Cultural Work’ (30 October 1944), in Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, 3 (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1967); Judith Banister, China’s Changing Population (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991), 42; Yip, op. cit. (note 10), 190.

John Philip Emerson (ed.), Nonagricultural Employment in Mainland China, 1949–58, US Department of Commerce, Foreign Demographic Analysis Division, Bureau of the Census, International Population Statistics Reports, Series P-90, 21 (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1965), 92; J. Yudkin, ‘Medicine and Medical Education in the New China’ Journal of Medical Education, 33, 7 (July 1958), 519; J.Z. Bowers, ‘Medicine in Mainland China: Red and Rural’, Current Scene: Developments in Mainland China, 8, 12 (1970), 1–11.

Lei, op. cit. (note 6), 196–7; Michael Kau and John Leung (eds), ‘Directive on Work in Traditional Chinese Medicine’ (30 July 1954), ‘Implementing Correct Policy in Dealing with Doctors of Traditional Chinese Medicine’ (20 October 1954), The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949–76, Vol. 1 (Armonk, NY: Sharpe, 1986), 464–6, 486–91; Michael Kau and John Leung (eds), ‘Talk with Music Workers’ (24 August 1956), in The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949–76, Vol. 2, 94–8.

Fu Lien-Chang, ‘Summing-up of the Ninth General Conference of the Chinese Medical Association held in Peking on December Fourteenth to Seventeenth, 1952’, Chinese Medical Journal, 71 (March–April 1953), 160–1.

Jiangsu Provincial Archive: 3235, 41, yongjiu, 26 March 1951–18 April 1957.

Yang Nianqun, ‘Memories of the Barefoot Doctor system’, in Everett Zhang, Arthur Kleinman and Tu Weiming (eds), Governance of Life in Chinese Moral Experience (New York: Routledge, 2011), 131.

‘Directive on Public Health’ (26 June 1965) from Long Live Mao Tse-tung Thought, a Red Guard Publication, in Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, 9 (Secunderabad: Kranti, 1990).

Michael Kau and John Leung (eds), ‘Instruction on Leadership Work of Health Department of Military Commissions’ (3 April 1953), ‘Critique of Ministry of Public Health’ (October 1953), and ‘Comment on Department of Public Health’ (1953), in The Writings of Mao Zedong, Vol. 1, 339–40, 425, 441–2, 466 nn.

Red and expert was an idea promoted by Mao Zedong. Initially they were viewed as contradictory: reds were people with a correct political background and generally limited education; while experts had technical skills, a higher education and a poor class background. The dream was to combine the two, generally by transferring technical skill sets into the hands of people who were red. The barefoot doctors were an example of putting this ideology into practice.

Editor, ‘The Mao–Liu Controversy over Rural Public Health’, Current Scene, 7, 12 (1969), 1, 3; Everett M. Rogers, ‘Barefoot Doctors’, Rural Health in the People’s Republic of China: Report of a Visit by the Rural Health Systems Delegation, June 1978, Committee on Scholarly Communication with the People’s Republic of China (US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, NIH Publication 81-2124, November 1980), 45; Field, op. cit. (note 2), 420–5.

Re-education involved prohibiting practising medicine and backbreaking labour in the fields. By 1972, according to probably inflated numbers, about 330 000 urban medical personnel were settled permanently in the countryside, another 400 000 nurses and doctors were participating in two-year rural mobile medical teams and a final 100 000 medical workers were dispatched to the countryside from the military medical establishment. The decision to send urban doctors to the countryside greatly diminished medical capacity in the cities. J. Bonner, ‘Medicine and Public Health’, China Science Notes, 3, 1 (January 1972), 6; ‘Zunzhao Mao zhuxi guanyu “yingdang jiji de yufang he yiliao renmin de jibing” de jiaodao’ [Obey Chairman Mao’s guidance to ‘actively prevent and treat the people’s diseases’], Renmin ribao[People’s Daily] (26 June 1973); China Health Care Study Group, Health Care in China, an Introduction: The Report of a Study Group in Hong Kong (Geneva: Christian Medical Commission, 1974), 111; S.M. Hillier and J.A. Jewell, Health Care and Traditional Medicine in China, 1800–1982 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983), 107; Cao Hongxin, Li Huairong, Zhongguo Zhongyi yanjiuyuan [Chinese Medicine Research Institute], ‘Jiaoyu gongzuo’ [Pedagogical work], in Zhongguo zhongyi yanjiuyuan renwu zhi, 1955–2005 [Annals of Chinese Medicine Research Institute personnel, 1955–2005] (Beijing: Zhongyi guji chubanshe, 2005), 68.

Hu Teh-wei, ‘Health care services in China’s economic development’, in Robert F. Dernberger (ed.), China’s Development Experience in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), 234, 235, 246.

‘Directive’ op. cit. (note 22); E. Grey Dimond, ‘Medical Education and Care in People’s Republic of China’, Journal of the American Medical Association, 218, 10 (6 December 1971), 1554; Hillier and Jewell, op. cit. (note 26), 342, 347, 359, 360.

Fang, op. cit. (note 3), 109–11; David Lampton, ‘Economics, Politics, and the Determinants of Policy Outcomes in China: Post-Cultural Revolution Health Policy’ Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 12, 1 (1976), 44–8; Peter Wilenski, The Delivery of Health Services in the People’s Republic of China, International Development Research Centre, 56 (Canada: International Development Research Centre, 1979), 48.

Shanxi sheng Xiyang xian geming weiyuanhui [Xiyang County, Shanxi Province revolutionary committee], ‘Zai weisheng zhanshi shang shixing wuchan jieji zhuanzheng’ [Implement the dictatorship of the proletariat in the sanitation battle line], Yixue yanjiu tongxun, 8 (1975), 1; Fang, op. cit. (note 3), 14, 33; Edward Friedman, Paul G. Pickowicz and Mark Selden, Chinese Village, Socialist State (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), 207–8; Yang, op. cit. (note 21), 138; David Mechanic and Arthur Kleinman, ‘Ambulatory Care’, Rural Health in the People’s Republic of China, 31.