Abstract

Background:

Removal of an intrauterine device can be easily done when the string is visible during speculum exam. The task becomes challenging when the string is no longer visible.

Methodology:

The in-patient and out-patient medical records of all patients admitted for hysteroscopic-guided intrauterine device removal from January 2013 to December 2015 from a tertiary academic government hospital were retrieved and reviewed. Demographic data, intraoperative record, and post-operative course and outcome were obtained. Prior attempts on removal were also noted. Total operative time, type of IUD removed, operative findings and any complications encountered were recorded. The size and model of the hysteroscope were also noted.

Results:

Nineteen patients were included, twelve were of reproductive age and seven were already in their menopausal years. Majority were multigravida. Reasons for IUD removal for most patients were spotting, desire for pregnancy, and expired date of use. All patients had prior attempts of ultrasound guided IUD removal. Majority of patients had unremarkable post-operative course and no readmissions were noted.

Conclusion:

Hysteroscopic-guided removal of IUD is a superior option for management when ultrasound guided removal fails. Unnecessary major operation and complications were avoided. In the three – year experience, there has been no major complications and re-admissions related to the procedure. Hysteroscopic removal of IUD was shown to be an effective option after failed ultrasound-guided removal with low risk of complications.

Keywords: Hysteroscopy, intrauterine device removal, retained intrauterine device

INTRODUCTION

The use of intrauterine device (IUD) is a safe and effective method for long-term reversible contraception with minimal and tolerable side effects.[1] When the adverse events become intolerable, women seek consult for removal.[2,3] The method of removal of the device depends on the visibility of the string during speculum examination. In patients whose IUD has a visible string, removal can be safely done in an office setting and without anesthesia. Other clinicians advocate the use of ultrasound to aid in removing the device. When the latter fails, patients are then referred for hysteroscopy.[4]

In this institution, an established protocol of using hysteroscopy as a last resort in removing IUD is performed after ultrasound-guided attempt fails. When a lost IUD is suspected, evaluation is performed to see if the strings of the IUD can be seen or palpated through the cervical os. In cases when the string cannot be seen, a transvaginal ultrasound is performed to see whether the IUD is within the uterine cavity, embedded in the uterine wall or expelled into the peritoneal cavity. If the transvaginal ultrasound shows that the IUD is in the uterine cavity, attempts are made to remove the IUD with uterine forceps with ultrasound guidance. If this fails, hysteroscopy is performed with removal of the IUD.

It is important for clinicians to be competent with the procedure and to avoid possible complications. This study aims to evaluate the patient characteristics and clinical outcomes of hysteroscopic-guided IUD removal performed in a tertiary academic government hospital from January 2013 to December 2015.

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted in a tertiary academic government hospital with an average of 50,000 consults per year in the combined outpatient clinics of obstetrics and gynecology.

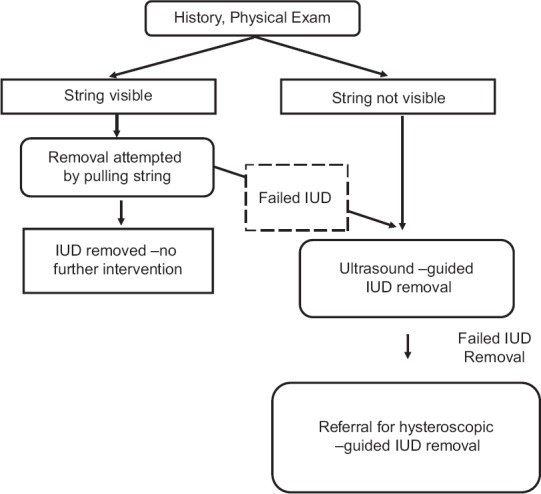

All patients were initially seen at the general gynecology clinic for evaluation, and attempts of removal were done before referral. The resident physician trainee follows an algorithm in removal of IUD [Figure 1]. Pelvic examination, including speculum examination, is performed to visualize the string. If the strings are visible, an attempt to remove the IUD with uterine forceps was performed. If this fails or in cases where the string is not visible, a transvaginal ultrasound is done to confirm the presence of the IUD in the uterus. Signs of displacement and perforation are recorded. After confirming the position of the IUD by transvaginal ultrasound, patients are asked to follow-up for ultrasound-guided removal. For premenopausal patients, removal is performed during their menses. When ultrasound-guided removal fails, the patients are referred for hysteroscopic-guided removal.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for patients consulting for intrauterine device removal

The registry of operative room procedures from January 2013 to December 2015 was used to obtain the list of patients who underwent hysteroscopic-guided removal of an IUD. The inpatient and outpatient medical records of these patients were retrieved and reviewed. Chart review started from their first consult at the general gynecology clinic to referral for hysteroscopy and admission, until 1 month after their operation. Demographic data, intraoperative record, and postoperative course and outcome were collected and logged on the data sheets. Age, gravidity, parity, body-mass index, medical history, menopausal status, and reason for removal were recorded. Prior attempts on removal were also noted. Size and model of hysteroscope used, postoperative course, and readmissions related to the procedure were recorded.

Descriptive statistical analysis was used and data were expressed as frequency, percentage, mean ± standard deviation, and range. All nineteen patients were included in the study. Outpatient charts were retrieved to monitor patient outcome up to 1 month after their operation.

The study was approved by the Institution's Ethics Review Board. The information obtained was kept anonymous and confidential. Each patient was identified solely by their case number.

RESULTS

There were nineteen patients who were admitted for hysteroscopic-guided IUD removal from January 2013 to December 2015. The average age of the patients was 32 and most were multigravida. Baseline demographic characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Of the 19, only 3 had their own sources of income – a teacher, a nursing assistant, and a self-employed mother. The rest are dependent on their relatives for support.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics

| Mean±SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 32±9 | 31-67 |

| Gravidity | 2±1 | 1-5 |

| Parity | 1±1 | 1-5 |

| BMI | 24.12±2.88 | 19.4-30 |

| Duration of IUD use | 5±10 | 3-40 |

BMI: Body mass index, SD: Standard deviation, IUD: Intrauterine device

Reasons for removal included pain, spotting, desire for pregnancy, expired date of use, removal with concomitant operative procedure, infected fragment, pain, and desire for permanent sterilization [Table 2]. The most common consult for IUD removal was due to spotting.

Table 2.

Reasons for removal of intrauterine device

| Reasons | Total (n=19), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Spotting | 8 (42) |

| Desire for pregnancy | 3 (16) |

| Expired date of use | 3 (16) |

| For removal with concomitant operative procedure | 2 (10) |

| Infected IUD | 1 (5) |

| Pain | 1 (5) |

| For bilateral tubal ligation | 1 (5) |

IUD: Intrauterine device

Of the 19 patients, 7 (37%) were already menopausal [Table 3]. For both menopausal and premenopausal women, spotting was the most common reason for removal. For the premenopausal and menopausal groups, the average duration of IUD use was 8 and 22 years, respectively. The Copper T IUD was seen more frequently among women in the premenopausal groups.

Table 3.

Age, duration of use, reason for removal and type of IUD according to menopausal status

| Premenopausal (n=12) | Menopausal (n=7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (average years±SD) | 38±5 | 53±6 |

| Duration of use (average years±SD) | 8.17±5.84 | 22±9.22 |

| Reason for removal (top 3 reasons) | Spotting (33%) | Spotting (57%) |

| Desirous of pregnancy (25%) | Due for removal (42.8%) | |

| With concurrent OR (16.7%) | ||

| Type of IUD | ||

| Copper T | 11 | 2 |

| Lippes loop | 1 | 5 |

IUD: Intrauterine device, n: Number of patients, SD: Standard deviation, OR: Operation

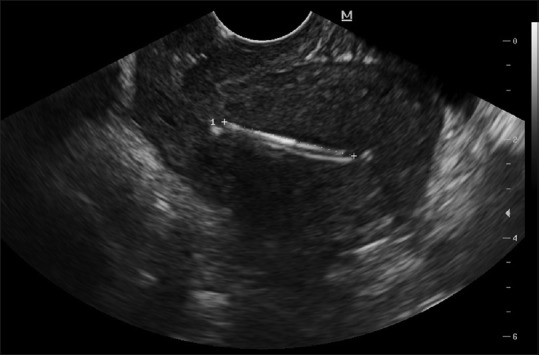

All patients had previous attempts of removal before referral and were initially seen at the general gynecology clinic for evaluation. The physician followed the algorithm in removal of IUD [Figure 1]. An attempt to remove the IUD with uterine forceps was performed, and if this maneuver fails or in cases where the string is not visible, a transvaginal ultrasound was done. The presence of the IUD in the uterus was confirmed [Figure 2] with note of any signs of displacement and/or perforation. Based on our records, 26 patients underwent successful ultrasound-guided removal from 2011 to 2015. For premenopausal patients, removal was timed during their menses. When ultrasound-guided removal fails, the patients were then referred for hysteroscopic-guided removal.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound picture of intrauterine device. IUD is in place with the long arm of the IUD (Copper T) visible, anteroposterior view

Management of all 19 patients followed the institution's algorithm. There were two patients who had their IUD removed concomitant with an operative procedure (one underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy for submucous myoma and another underwent laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy). Both patients initially underwent ultrasound-guided IUD removal, as the strings were not visible during their first consult, but these were unsuccessful.

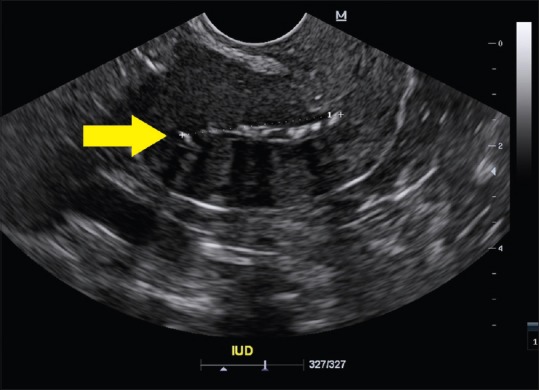

One patient had her IUD removed due to an infected device. She complained of intermittent pelvic pain and sought consult. The IUD (Copper T-IUD) was successfully removed during the initial consult, but the short arm was noted to be missing. On transvaginal sonography, it was noted to be embedded into the myometrium, prompting referral for hysteroscopy [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Ultrasound picture of intrauterine device. Displaced intrauterine device in anteroposterior view. Note the portion embedded at the fundal area (yellow arrow)

Intraoperative findings

There were 2 types of IUD retrieved – Copper T IUD (68%) and Lippes Loop IUD (32%). The majority of IUD removed on the premenopausal group was the Copper T IUD. The Lippes Loop IUD was noted to be inserted earlier (ranging from 1973 to 1993) while the Copper T-IUD became more common in recent years (1997–2012).

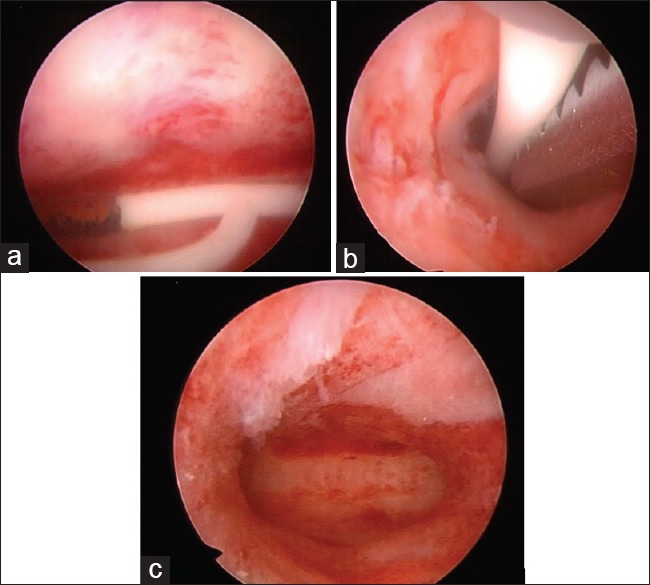

One case of retained IUD was that of a 51-year-old multigravida with a Copper T IUD inserted 16 years ago [Figure 4]. The rusted area of the right arm of the IUD can be seen. A semirigid Fr 3 grasping forceps was used to remove the IUD. The depression on the endometrium by the IUD is seen at the fundal area. The second case was that of a 58-year-old multigravida who had a Lippes loop inserted 23 years ago [Figure 5]. An initial attempt was done using a semirigid forceps by grasping the string. The IUD was eventually removed using rigid forceps inserted lateral to the hysteroscope.

Figure 4.

Hysteroscopic pictures. Retained intrauterine device for 16 years in a 51-year-old G3P3 (3003). Note the rusted areas on the short arm (a). Removal done using a semirigid Fr. 3 grasping forceps (b). Endometrium after removal of the intrauterine device. Note the indentation due to the device at the fundal area (c)

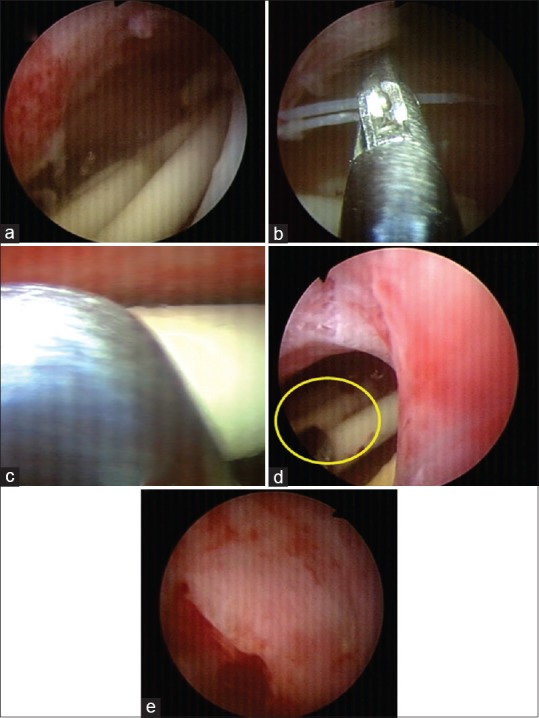

Figure 5.

Hysteroscopic pictures. Retained intrauterine device for 23 years in a 58-year-old G4P4 (4003). Lippes loop intrauterine device (a). Removal attempted using a semirigid Fr. 3 forceps by grasping the string (b). Removal attempted using a semirigid Fr. 3 forceps by grasping the loop (c). Intrauterine device removed using a rigid forceps, seen at the periphery (yellow circle) (d). Endometrium after removal of the intrauterine device (e)

The sonographic evaluation on the type of IUD was all consistent with the intraoperative findings. There were two cases of embedded IUD. The first case was the infected fragment, which was embedded at the anterior myometrium, near the level of the uterine isthmus. The second case was a Lippes loop, with its tip partially embedded at the fundal area. Both patients had minimal blood loss intraoperatively and had stable postoperative course. There was one case with a submucous myoma where the Lippes loop was noted to be displaced superiorly by the myoma, occupying the upper half of the intrauterine cavity. For this patient, the IUD was first removed, and transcervical resection of the myoma was done. The rest of the patients had their IUD inside the uterine cavity, with no perforations.

All patients had minimal blood loss. The procedures were done in a short amount of time, with an average of 5 min (including cervical dilatation). The longest procedure noted was 4 h and 13 min. This included the concurrent procedure of laparoscopic oophorocystectomy with conversion to an exploratory laparotomy and surgical staging for ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The hysteroscopic procedure itself was done in 4 min.

Scope and instrument used

Two sets of hysteroscope were used: a diagnostic hysteroscope and an operative hysteroscope. In 12 of the cases, the diagnostic hysteroscope was used. Initial attempt to grasp the IUD was done using the semirigid forceps. When this failed, the larger rigid forceps with wider tip was used for retrieval. The larger forceps were also used in cases where there were no strings attached to the device. Eight patients underwent operative hysteroscopy for removal. One patient underwent both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy due to failure of retrieval using the diagnostic hysteroscope. The surgeons used the operative hysteroscope and a resectoscope loop to remove the IUD.

Postoperative outcomes

All patients had stable postoperative course, and most were sent home a day after the operation. Only one patient had to stay for 13 days due to an intraoperative finding of malignancy. No patients were readmitted.

DISCUSSION

Safe and highly effective, the IUD is one of the most frequently used reversible contraceptive methods worldwide. In a study of 14 developing countries – Bolivia, Columbia, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Peru, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Turkey, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Philippines, and Vietnam, its median use is 8.6%. The IUD is used by 4.1% of women in the Philippines.[1] In an article published by the ESHRE Capri Workshop Group,[2] the IUD is the second most commonly used contraception, with over 150 million users worldwide. Similar to the study produced by Marie Stopes International and the World Health Organization, its use is also greatly varied, from 2% in Sub-Sahara Africa to 78% in North Korea.[1]

Side effects of IUD include vaginal bleeding and dysmenorrhea a few months postinsertion,[3] pain, expulsion, perforation, and migration.[2,4] Women consult for removal when side effects become apparent.[2] Other reasons for discontinuation include nonvisible strings, dislocation, desire for pregnancy, and expired date of use.[4] In a retrospective study done in Turkey, the most common cause of discontinuation is expired date of use (55% of those who consulted for removal), followed by desire for conception (51%) and IUD-related adverse events (51%).[5] In the present study, the most common reason for discontinuation was spotting. However, the study did not include all patients consulting for removal of IUD and was limited to those patients who were referred for hysteroscopic-guided removal of IUD.

Most of our patients consulted for IUD removal due to symptoms. Such was the case of the second oldest patient included in the sample. At the age of 58, she had her IUD inserted 23 years ago. There was no prior consult for removal because she was asymptomatic until a year before consult when she noted vaginal spotting.

Because the IUD is inert, patients may tend to forget that they still have an IUD. This was shown by the oldest patient, who at the age of 64, had forgotten that she had an IUD for 40 years already. She was not sure whether she had it removed before and sought consult to confirm if the IUD was still inside her uterus. Due to the failed ultrasound-guided removal, she was referred for hysteroscopy.

In some patients, the removal of the IUD was requested because of a concurrent procedure. One patient was admitted for abnormal uterine bleeding secondary to submucous myoma and another admitted for removal of an ovarian new growth. For the first patient, she was admitted for correction of anemia and subsequent transcervical resection of myoma. She was premenopausal and the Lippes Loop IUD was inserted 22 years ago. She had a relatively long hospital stay (11 days) as blood transfusion was initially done before the procedure (transcervical removal of IUD and resection of submucous myoma). The second patient underwent hysteroscopic removal of the IUD and operative laparoscopy for the ovarian new growth. Frozen section of the ovarian mass was consistent with endometriod adenocarcinoma. She underwent exploratory laparotomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and surgical staging.

Office removal is feasible if the string is visible. Extraction of the IUD is facilitated by applying controlled traction on the string. In instances where no string is visible, possibilities include spontaneous expulsion of the IUD, retracted or torn off string, misplacement within the cavity, intramural penetration, or extrauterine location. A sonographic examination is requested to ensure that the device is in place. Otherwise, pelvic X-ray might be necessary to rule out perforation.[6,7] Once the IUD is confirmed to be within the cavity, office removal with use of additional modalities (e.g., ultrasound guidance with hook, ring forceps, or alligator forceps) can be applied. It was proposed in a study in Miami to use ultrasound-guided removal of IUD as the first-line management given its ease of accessibility. Furthermore, this is more acceptable to patients because it is a noninvasive procedure.[8] If removal is unsuccessful, another attempt may be offered which will be done under general anesthesia after cervical ripening with misoprostol.[7]

Our training institution has adopted the presented algorithm in evaluating patients consulting for IUD removal. Ultrasound-guided removal of IUD is done as first-line management in patients with no visible strings. The procedure is done during menses in premenopausal patients and after cervical ripening in menopausal patients. When the procedure fails, patients are then referred for hysteroscopy.

Hysteroscopic-guided removal of IUD may be done after failed ultrasound-guided removal. Unnecessary major operation and complications can be avoided through this minimally invasive procedure. It also offers the advantage of short hospital day, minimal blood loss, and minimal immediate and late complications.[9] The diagnostic hysteroscope has a smaller diameter, offering less cervical manipulation compared to operative hysteroscopy, and is therefore the preferred method during hysteroscopic-guided removal. Using semirigid forceps in retrieving the device under direct visualization renders the procedure safe with very minimal risk of complication. However, due to its small bite, it can only grasp the string. A grasper with wider bite is therefore needed in cases where the string is absent. In this case, the diagnostic hysteroscope is utilized with the rigid forceps inserted laterally and visualized in the periphery during removal. In cases that these fail, operative hysteroscopy is done.

CONCLUSION

Hysteroscopic-guided removal of IUD is a superior and safe option for management in cases where ultrasound-guided removal failed. Unnecessary major operation is avoided with this procedure. In the 3-year experience observed, there has been no major complication and readmissions related to the procedure. The findings support the protocol of the institution of the performance of hysteroscopic-guided removal of IUD as the next step after failed ultrasound-guided removal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohamed MA, Rachael KS, John C, Thoai DN, Iqbal HS. London: World Health Organization and Marie Stopes International; 2011. Long-Term Contraceptive Protection, Discontinuation and Switching Behaviour: Intrauterine Device (IUD) use Dynamics in 14 Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosignani PG ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Intrauterine devices and intrauterine systems. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:197–208. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritz M, Speroff L. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prabhakaran S, Chuang A. In-office retrieval of intrauterine contraceptive devices with missing strings. Contraception. 2011;83:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tugrul S, Yavuzer B, Yildirim G, Kayahan A. The duration of use, causes of discontinuation, and problems during removal in women admitted for removal of IUD. Contraception. 2005;71:149–52. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchi NM, Castro S, Hidalgo MM, Hidalgo C, Monteiro-Dantas C, Villarroeal M, et al. Management of missing strings in users of intrauterine contraceptives. Contraception. 2012;86:354–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung VY. A 10-year experience in removing Chinese intrauterine devices. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:219–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma U, Astudillo-Dávalos FE, Gerkowicz SA. Safe and cost-effective ultrasound guided removal of retained intrauterine device: Our experience. Contraception. 2015;92:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi SS, Goel M, Jain S. Hysteroscopic management of intra-uterine devices with lost strings. Br J Fam Plann. 2000;26:229–30. doi: 10.1783/147118900101194652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]